Abstract

Postpartum hemorrhage is a great cause of maternal morbidity and mortality worldwide with these effects being worse in developing countries. Uterine atony is the commonest cause. Esike's three brace suture technique is a novel simple but effective method that was used to successfully control life-threatening postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony in two women with the preservation of their uterus. Vicryl or chromic catgut 2 was used to apply compression sutures on the atonic uterus. This simple, effective, less invasive, easy to learn uterine-sparing technique is presented for further evaluation and possible wider use in saving the lives of our PPH patients and sparing their uteri.

Keywords: Control, Esike's technique, postpartum hemorrhage, Contrôle, technique d’Esike, hémorragie du post-partum

Résumé

L’hémorragie du post-partum est une cause importante de morbidité et de mortalité maternelles dans le monde, ces effets étant pires dans les pays en développement. L’atonie utérine est la cause la plus fréquente. La technique de suture à trois accolades d’Esike est une nouvelle méthode simple mais efficace qui a été utilisée avec succès contrôler l’hémorragie post-partum potentiellement mortelle due à l’atonie utérine chez deux femmes avec la préservation de leur utérus. Vicryl ou chromique catgut 2 a été utilisé pour appliquer des sutures de compression sur l’utérus atone. Cette technique d’épargne utérine simple, efficace, moins invasive et facile à apprendre est présenté pour une évaluation plus approfondie et une utilisation plus large possible pour sauver la vie de nos patientes souffrant d’HPP et épargner leur utérus.

INTRODUCTION

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality all over the world and is more devastating in developing countries.[1,2,3] It accounts for one-quarter of maternal mortality worldwide with about 79%[4] due to uterine atony. Although the armamentarium at the disposal of Obstetricians for combating PPH is many, they must continue to search for and report new management modalities, especially those that are simple, safe, effective, and easy to learn to prevent PPH, especially those due to uterine atony. I report one of such methods “the ESIKE’S THREE-BRACE SUTURE TECHNIQUE” that helped to arrest uncontrollable and life-threatening PPH in two women.

CASE REPORTS

Case one

Mrs. N. C. was a 35-year-old booked G3P2+O trader with 2 living children who came in active phase of labor in our center. She had vacuum delivery due to fetal distress in the second stage of labor and developed life-threatening PPH that defiled all available controlling measures. Physical examination revealed an anxious lady who was afebrile, anicteric, and markedly pale with a thready pulse rate of 120 beats/min and a 22-week-sized flabby uterus. The vulva was smeared with blood and there was active bleeding per vaginam. There were no genital tract lacerations or retained products of conception.

All the available conventional options to control the PPH were unsuccessful. She was started on blood transfusion and taken to the operating theater for hysterectomy, but the Esike's three-brace suture technique was performed. It controlled the PPH and there was no further need for hysterectomy.

Case two

Mrs. O. H, a booked G7P3+3A3 business woman, was admitted via the antenatal clinic at 39 weeks and 2-day gestation for stabilization and delivery because of severe preeclampsia. She had a cesarean section due to failed induction and bled profusely after the surgery. She was taken back to the theater and the uterus was re-examined. There were no lacerations. The operation site was intact and not bleeding, but the uterus was flabby. All efforts to control the hemorrhage were not successful and hysterectomy was contemplated. The Esike's three-brace suture technique was attempted and was able to arrest the hitherto uncontrollable hemorrhage.

The Esike's technique

Six polyglactin No. 2 or chromic catgut No. 2 sutures with round-bodied needles were required to carry out the Esike's technique.

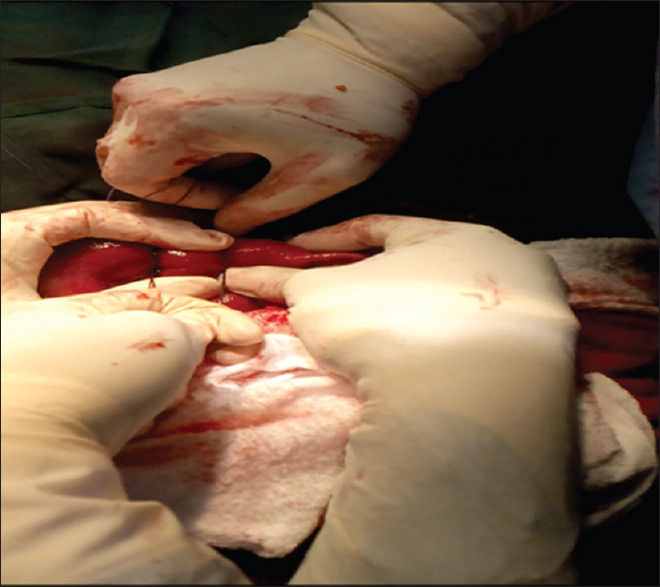

Placing the sutures

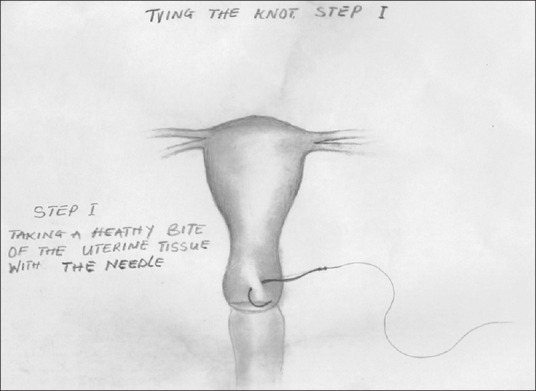

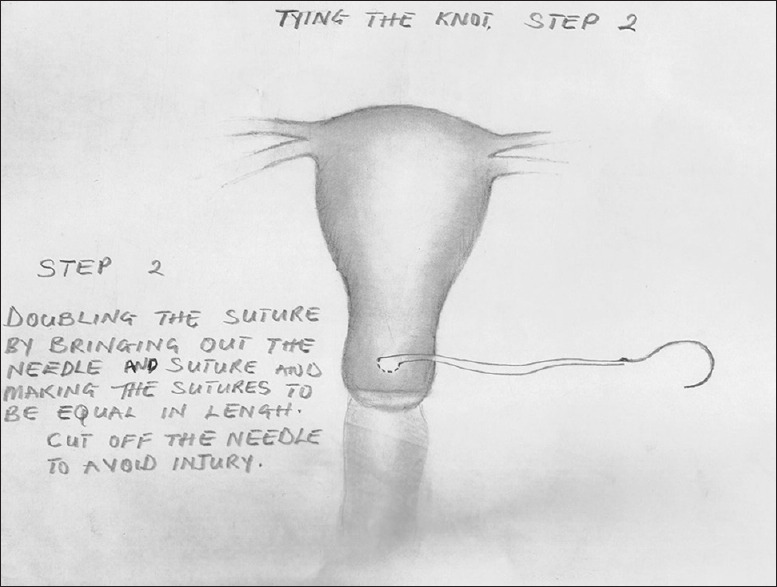

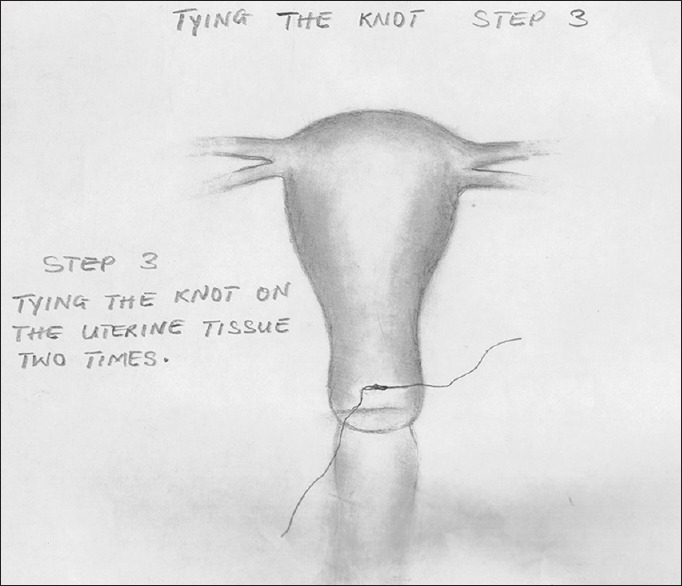

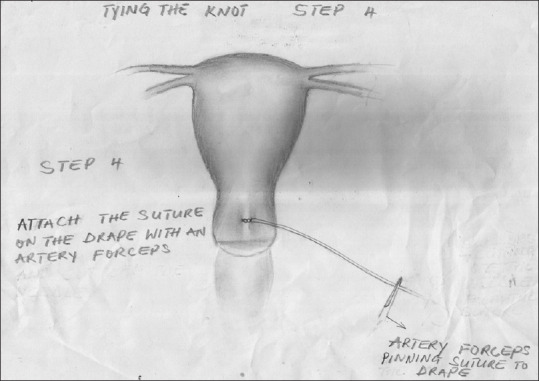

Using the first polyglactin No. 2 or chromic catgut No. 2 suture which was mounted on a round bodied needle, the usual needle with suture that is used for cesarean sections, I inserted the needle of the first suture (suture one) into the uterine tissue (covering about 3–4 cm) just above the bladder reflection, at the lower segment of the uterus at about 2 cm from the right edge of the uterus [Figure 1]. The needle was brought out and the suture was drawn out so that the two lengths of sutures were equal [Figure 2]. The needle was cut to avoid injury and the suture knotted twice around the uterine tissue [Figure 3] and the two stands of suture were clipped with mosquito artery forceps on the drape, away from the operating site [Figure 4].

Figure 1.

Inserting the needle into the uterus (step 1)

Figure 2.

Drawing out the needle and suture to make the two strands of the suture equal (step 2)

Figure 3.

Tying the knot around uterine the tissue (step 3)

Figure 4.

Pinning the tied suture strands on the drape (step 4)

The second suture (suture 2) was inserted at the center of the anterior part of the lower segment of the uterus at a slightly different level from suture one but still above the bladder reflection. This suture was also drawn to the same length, the needle was cut off, and the suture secured on the uterus by tying two knots around the uterine tissue. The sutures were brought together and clipped with an artery forceps on the drape, away from the operation field.

Suture three was also inserted at about 2 cm from the left lateral aspect of the anterior aspect of the lower segment of the uterus above the bladder reflection at a different level from sutures one and two. The suture was drawn out and made equal in length. The needle was cut off and the suture tied around the uterine tissue. The sutures were brought together and were clipped to the drape away from the operating field.

Then similarly, sutures four, five and six were inserted at varying levels at the lowest one-fifth of the posterior aspect of the uterus each time, taking healthy bites of the uterus of about 3–4 cm for each bite, drawing up the lengths of the suture to be equal, cutting off the needle, tying it with two knots and pinning the two strands of suture on a drape, away from the operation site. Suture four was inserted at the right lateral aspect of the uterus, at about 2 cm from the right lateral edge of the posterior, aspect of the uterus. Sutures five and six, were similarly inserted at slightly different levels at the center and left lateral aspects with suture six at about 2 cm from the left lateral border of the uterus posteriorly at a slightly different level from the other two sutures.

Tying the sutures

Now that the sutures had been tied on the uterus, proceed with the technique as follows:

Pick up the middle sutures (sutures 2 and 5) and position them above the uterus ready for tying [Figure 5]. With the assistant slowly but firmly and continuously compressing the uterus as much as possible, the middle sutures (sutures two and five) are firmly tied, taking the slack as the uterus is compressed until the uterus cannot be compressed further [Figure 6].

Figure 5.

Sutures 2 and 5 (the middle surures) are selected and positioned for tying

Figure 6.

Note the assistant firmly compressing the uterus while the sutures take the slack as they, the sutures, are being tied

Tying sutures one and four

The right sutures (sutures one and four) were picked up and positioned for tying above the uterus at about 4 cm from the cornu. With the assistant slowly but firmly compressing the right part of the uterus [Figure 7], the sutures were tied with two or three knots, taking up the slack as the uterus is being compressed.

Figure 7.

The uterus being compressed as the left lateral sutures (sutures three and six were tied

Tying sutures three and six

Pick up sutures three and six and position them for tying at about 4 cm from the left conus. With the assistant compressing the left part of the uterus, the left sutures (three and six) were slowly but firmly tied, taking up the slack of the compressed uterus in the process [Figure 7].

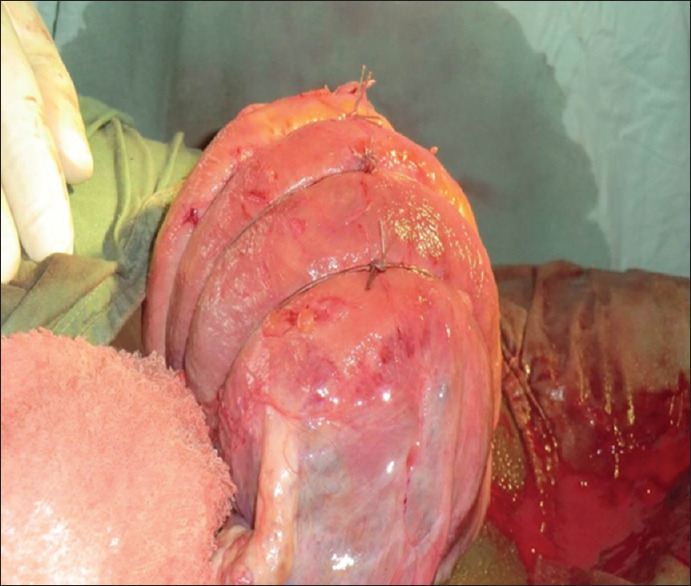

With the tying of these sutures, all the three pairs of sutures were tied and cut and the technique was finished [Figure 8].

Figure 8.

How the uterus looks after Esik's three-brace suture technique

I observed for bleeding by inspecting the vulva for some minutes until satisfied that there was none. The uterus was then replaced and the anterior abdominal wall was closed in layers and the wound was dressed.

DISCUSSION

PPH is a major cause of maternal morbidity and mortality all over the world, and uterine atony is the most common cause.[5,6,7] Although uterotonic drugs are used to prevent PPH[7,8] after delivery, uterine atony persists in some cases necessitating further measures including surgery to stop the PPH and save the woman's life. Hysterectomy is the surgical means of last resort to prevent maternal mortality.[7] Before resorting to hysterectomy, however, there are other more conservative uterus-sparing maneuvers that could effectively stop the PPH.[9,10] The Esike’ three-brace suture technique if properly performed could be one of them.

It is simple, effective, and easy to learn and conserved the uterus in both cases presented. The issues of simplicity, effectiveness, and conservation of the uterus in the management of PPH come into consideration, especially in the rural settings where the doctors may not be able to perform a hysterectomy.

Although preservation of the uterus is not a major consideration if PPH threatens a woman's life, the issue of uterine preservation whenever possible for women, especially those who have not completed their reproductive career, especially in Africa, is very important and may not be fully appreciated in other more advanced climes. To such women, this simple and less invasive technique could help them meet their aspiration.

CONCLUSION

PPH is a major cause of maternal mortality. To prevent mothers from dying from it, any good method used to control it, especially surgical methods must be simple, effective, quick to carry out, and easy to learn. Esike's three-brace suture technique meets these criteria in addition it helps to conserve the uterus.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.MCHIP. Prevention and Treatment of Post Partum Hemorrhage at Community Level – A Guide for Policy Makers, Healthcare Providers, Donors, Community Leaders and Program Managers. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Jehpiego; 2011. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Idrisa A, Njoku AE. Primary post partum hemorrhage at the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital: A ten-year review. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;29:29–33. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization (WHO). Recommendations for the Prevention of Post Partun Hemorrhage (Summary of Result from WHO Technical Consultation October 2006) Geneva: WHO; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adetoro OO. Prevention and treatment of post partum haemorrhage. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;27:36–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stephenson P. Active Management of the Third Stage of LABOR: A SIMPLe Practice to Prevent Post partum Hemorrhage, USAID Global Health Technical Brief. June. 2005. [Last assessed on 2019 Jul 20]. Available from: http://www.maqweb.org/techbriefs/tb13activemgmt.shtml .

- 6.Shittu OS, Otubo JA. Post partum hemorrhage. In: Agbola A, editor. Text Book of Obstetrics and Gynecology for Medical Students. 2nd ed. Ibadan: Heinnman Educational Books (Nig) Plc; 2006. pp. 481–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwawukume EY. Post partum hemorrhage. In: Kwawukume EY, Emuveyan EE, editors. Comprehensive Obstetrics in the Tropics. 1st ed. Dansoman: Asante and Hittscher Printing Press Limited; 2002. pp. 115–21. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arulkumaran S, Johnson T. Improving women's health (Editorial) Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2012;119:S1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gharoro EP. Surgical Management of Post Partum Hemorrhage. Proceedings of the 41st Scientific Conference and Annual General Meeting of the Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics of Nigeria (SOGON) Benin. 2007:207–17. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christopher BL. Surgical Management of Post Partum Hemorrhage, Priorities in Reproductive Health, Proceedings of the 8th International Scientific Conference and the 44th Annual General Meeting of the Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics of Nigeria (SOGON), Abuja. 2010:156–62. [Google Scholar]