Abstract

Aim:

The aim of the study was to evaluate and compare the retreatability of BioRoot RCS and AH Plus sealer with two different retreatment file systems using cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) for assessing the filling remnants.

Materials and Methods:

A total of sixty mandibular premolars with single and oval root canals were prepared till size F3 and obturated with GP/AH Plus (Group 1) and GP/BioRoot RCS (Group 2). Canals were then retreated using two different retreatment file systems – ProTaper Universal Retreatment (PTUR) system and NeoEndo Retreatment system. The ability to re-establish working length (WL) and apical patency was recorded, and the percentage volume of residual filling material was evaluated using CBCT at the coronal, middle, and apical thirds. Data from the study were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance with Pearson's Chi-squared analysis and the Kruskal–Wallis test.

Results:

No statistically significant difference was found in the amount of residual sealer (AH Plus and BioRoot RCS) after retreatment throughout the whole study (P > 0.05) at various root canal levels. Furthermore, the BioRoot RCS group retreated with the PTUR system showed a higher frequency of failure in re-establishing WL and regaining apical patency than the other groups.

Conclusion:

Complete removal of root canal sealers could not be achieved regardless of the type of sealer used and the retreatment technique employed. Furthermore, in clinical settings, the retreatability of novel BioRoot RCS may be deemed feasible.

Keywords: BioRoot RCS, cone-beam computed tomography, retreatment

INTRODUCTION

The aim of the root canal retreatment is to disinfect the root canal space adequately to facilitate periradicular healing. To achieve this objective, complete removal of root canal filling material is required as the remnants act as a mechanical barrier between the intracanal disinfectants and microbes in inaccessible areas such as dentinal tubules and isthmuses.[1]

BioRoot RCS (Septodont, Saint Maur des Fosses, France) is a novel powder/liquid hydraulic tricalcium silicate-based cement and has been reported to have lower cytotoxicity than other conventional root canal sealers, may induce hard tissue deposition,[2,3] and has antimicrobial activity,[4] but little is known regarding its removal.

Micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) and cone-beam CT (CBCT) provide three-dimensional visualization of the entire root canal system without the need for tooth destruction and can subjectively analyze the filling remnants with minimal operator bias.[5]

The objective of this research was to assess and compare the retreatability of Bioroot RCS and AH Plus sealer from the root canal with two different rotary Ni-Ti retreatment systems (ProTaper universal retreatment [PTUR] files and NeoEndo retreatment files) using CBCT as the assessment method of the residual filling material. The null hypothesis stated that there was more percentage of residual filling material in the root canals obturated with GP/BioRoot RCS in comparison to GP/AH Plus sealer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This in vitro study was done in the Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics and approved by the institutional ethical committee (Dean/2019/EC/1149). A pilot study was conducted before beginning the main study with two samples per group. The mean and standard deviation were calculated, and the values were substituted in software G*Power 3.1.9.2. (Heinrich Heine University, Dusseldorf, Germany; Erdfelder, Faul, & Buchner, 1996) giving power of study as 95.34% with a total sample size of 60 (15 per group).

A total of 60 freshly extracted single-rooted mature mandibular premolar human teeth were selected and disinfected by immersing in 3% hypochlorite solution (Septodont, Saint Maur des Fosse's, France) for 7 days and then stored in 0.9% saline solution until use. Single and oval root canals with mature apex were verified by taking radiographs in both buccolingual and mesiodistal directions.

Teeth with severe root curvatures of >25°, presence of more than one root canal, root fillings and canal obliteration, and teeth with open apices were excluded from the study. The samples were decoronated with a diamond disc to form standardized root samples with an average of 16 ± 1 mm length.

The apical patency was ensured by introducing size #10 K-file (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) just beyond the apical foramen, and subsequently, working length (WL) was calculated to be 1 mm short from this measurement. The canals were prepared by ProTaper Gold Rotary System (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) in a brushing motion up to size F3 (speed: 300 rpm; torque: 3.0 N-cm) in a crown down manner.

Irrigation with 2 mL of a 3% NaOCl solution (Septodont, Saint Maur des Fosse's, France) was performed after each instrument. Finally, instrumented canals were rinsed with 1 ml of 17% EDTA (Prevest Denpro Ltd. Jammu, India) for 1 min followed by 2 mL of 3% NaOCl for 30 s using a 30G side-vented irrigating needle (Neoendo; Orikam Healthcare India Private Ltd.) placed 1 mm short of the WL. Subsequently, the canals were irrigated with normal saline and dried with paper points (#30, Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland). Master GP cones (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) were selected for each canal and evaluated for adequate fitting by checking the tug-back.

The samples were randomly divided into two groups (n = 30: in each group) depending on the sealer used for root canal obturation-

Group 1: Canals obturated with GP with AH Plus (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland)

Group 2: Canals obturated with GP with BioRoot RCS (Septodont, Saint Maur des Fosse's, France).

The sealers were mixed as per the manufacturer's instructions and applied to the root canal walls using a lentulospiral (Mani Inc). After this, the master GP cone was coated with the respective sealer and inserted up to the WL of the canal along with accessory GPs through cold lateral compaction technique. The excess GP was cut using a heat carrier, and orifices were sealed with temporary filling material (Cavit-G, ESPE-Premier, Norristown, PA, USA). The samples were then stored in a humidified chamber (100% humidity and 37°C) for 3 weeks to allow the sealers to set.

At the end of the above-mentioned procedures, all the specimens were numbered and fixed in wax arches followed by scanning using CBCT unit (Carestream Dental CS 9300 Select CBCT; Carestream Dental LLC 3625 Cumberland Blvd. Ste. 700 Atlanta). The scanning parameters were kept constant for every scan: 90 kV, current of 10 mA, exposure time of 19.96 s, resolution of 630 μm, a 2.5 mm thickness of aluminium filter with voxel dimension of 90 μm × 90 μm × 90 μm, and having a FOV of 5 cm × 5 cm.

Volume rendering and multiplanar volume reconstruction were performed to calculate the volume of filling remnants at various root canal sections using the “Anatomage in vivo three-dimensional imaging” dental software.

The specimens in each group were then randomly divided into two subgroups (n = 15) based on the retreatment method employed.

Group 1A: Canals obturated with GP and AH Plus sealer; retreatment with NeoEndo retreatment files

Group 1B: Canals obturated with GP and AH Plus sealer; retreatment with PTUR files

Group 2A: Canals obturated with GP and BioRoot RCS; retreatment with NeoEndo retreatment files

Group 2B: Canals obturated with GP and BioRoot RCS; retreatment with PTUR files.

Hedstrom files were also used in combination with the retreatment files.

A NeoEndo Retreatment file N1 (#30/0.09) was used for coronal one-third, N2 (#25/0.08), for middle-one third, and N3 (#20/0.07), for apical one-third of the obturated root canals. Files were used in circumferential filing motion in a crown-down approach using a torque-controlled motor at a speed and torque of 350 rpm and 1.5 N-cm, respectively. On each withdrawal, the files were cleaned with gauze to remove the adherent filling material and debris and inspected for any deformation.

ProTaper Universal Ni-Ti rotary retreatment instruments were used in a crown-down manner using a brushing action with lateral pressing movements according to the manufacturer's instructions. The instruments were activated by the torque-controlled motor at 500 rpm. D1 file (#30/0.09) was used for initial penetration and removal of filling in the coronal third; D2 file (#25/0.08) was used up to the middle third, and finally D3 file (#20/0.07) was used up to the full WL.

Finally, ProTaper Gold instrument F3 (#30/0.09) was used for apical preparation up to established WL using the previous irrigation protocol. Smooth canal walls with no remnants observed on the last file/instrument used were considered for the completion of the retreatment procedure.

All retreatment procedures were carried out by the same operator in a blinded manner to reduce interoperator variability.

Re-establishing WL and apical patency were ascertained using size # 10 no. K files (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland).

Evaluation of remnants of filling material was done by CBCT imaging using the same settings and parameters as those for the first scan, measured in cubic millimeters by a single observer who was blinded to group assignment. The mean volume percentage values of residual filling material were calculated by dividing the volume of filling material covered after retreatment to the total filling material and multiplying by 100.

The analysis of the data was carried out using IBM SPSS statistics software version 21.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) with the level of significance set at “P < 0.05.” The mean residual filling material was expressed as a volume percentage (±standard deviation) of the total filling material. To assess differences among the groups, data analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance. Furthermore, Pearson's Chi-squared analysis and the Kruskal–Wallis test were applied to evaluate the potential differences between the two used sealers regarding the parameters of re-establishing WL and regaining apical patency.

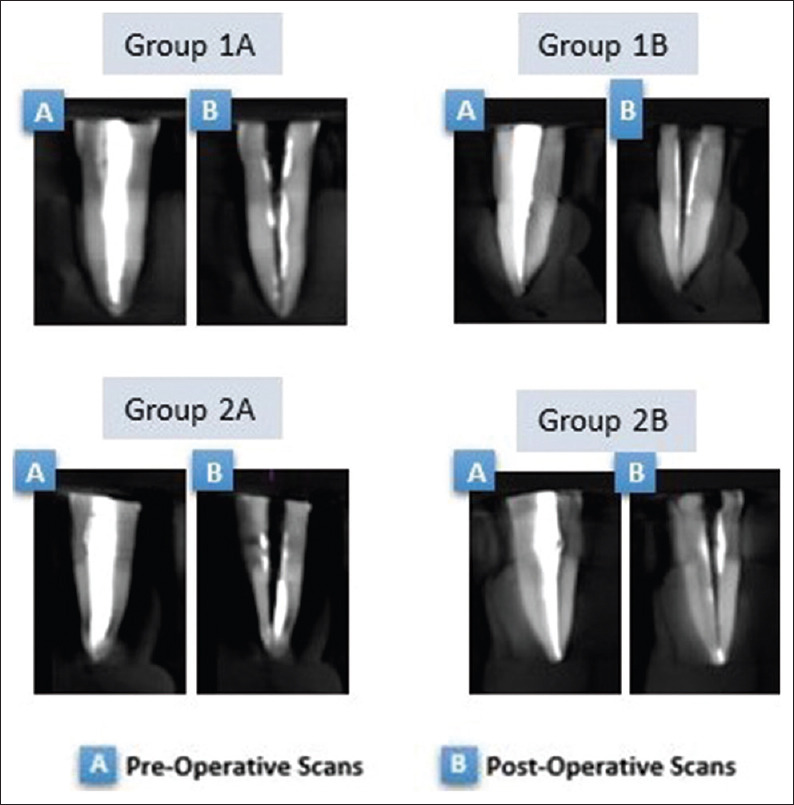

All the teeth samples were scanned using CBCT, but only one representative sample for each group has been demonstrated [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Representative cone-beam computed tomography images for each group (coronal sections) after obturation and after retreatment

RESULTS

Complete elimination of filling remnants from the root canal walls was not achieved in any of the groups. The mean volume percentage of root filling remnants was lowest in “Group 2A” in all thirds of the root canal and highest for “Group 2B” with no statistically significant differences in values of all the groups (P > 0.05).

When comparing the volume percentage of residual material at coronal, middle, and apical thirds of root canal within the group (intragroup) [Table 1], the tendency for more residuals was recorded in the apical sections and least in the coronal sections of the root canal; however, the difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Intragroup comparison of percentage of residual filling material at three different root canal levels

| Group | Canal segment | Percentage of residual filling material | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1A (AH plus with NeoEndo R) | Coronal-third | 22.98±16.40 | 0.974 | 0.386 (NS) |

| Middle-third | 29.99±21.77 | |||

| Apical-third | 34.63±29.09 | |||

| Group 1B (AH plus with PTUR) | Coronal-third | 15.64±11.86 | 0.260 | 0.772 (NS) |

| Middle-third | 18.89±16.98 | |||

| Apical-third | 19.51±17.84 | |||

| Group 2A (BioRoot RCS with NeoEndo R) | Coronal-third | 13.81±12.25 | 0.469 | 0.629 (NS) |

| Middle-third | 18.20±16.82 | |||

| Apical-third | 19.06±18.09 | |||

| Group 2B (BioRoot RCS with PTUR) | Coronal-third | 26.06±15.42 | 0.861 | 0.430 (NS) |

| Middle-third | 31.93±26.25 | |||

| Apical-third | 37.12±25.94 |

*One-way ANOVA test. ANOVA: Analysis of variance, PTUR: ProTaper Universal retreatment system, NS: Not significant, RCS: Root canal sealer

The WL was re-established in 100% of samples in Groups 1A, 1B, and 2A and 80% of samples of Group 2B, and the Pearson Chi-squared test indicated this difference as statistically significant (P = 0.024). BioRoot RCS group retreated with PTUR system (Group 2B) showed a higher frequency of failure in re-establishing WL than the other groups [Table 2].

Table 2.

Working length and apical patency re-establishment during retreatment for the different groups

| Group | WL re-established | Pearson χ2, P | Patency regained | Pearson χ2, P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Count (percentage within group) | Count (percentage within group) | |||||

|

|

|

|||||

| Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | |||

| Group 1A (n=15) | 15 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.024 (HS)* | 13 (86.7) | 2 (13.3) | 0.326 (NS) |

| Group 1B (n=15) | 15 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Group 2A (n=15) | 15 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (80.0) | 3 (20.0) | ||

| Group 2B (n=15) | 12 (80.0) | 3 (20.0) | 12 (80.0) | 3 (20.0) | ||

*Kruskal–Wallis test. WL: Working length, NS: Not significant, HS: Highly significat

In Group 1B, apical patency was regained in 100% of samples. However, patency was regained in only 86.7% of samples in Group 1A and 80% of samples in Groups 2A and 2B. BioRoot RCS groups (Group 2A and 2B) showed a higher frequency of failure in regaining apical patency than AH plus groups (Group 1A and 1B), but this difference was found to be statistically nonsignificant (P > 0.05) [Table 2].

DISCUSSION

Complete removal of existing root filling material during retreatment is important for the effective disinfection of the canal system.[6] The findings of the present study revealed that no retreatment technique was found to be capable of completely removing the obturating material, which is in accordance with the previous studies.[7,8,9,10]

Anatomical variations are considered to be one of the main confounding factors for comparability of the groups, and in order to minimize these variables, experimental groups have been standardized in the present study by taking extracted human mandibular premolars with single and oval root canal of approximately similar dimensions. This was controlled by taking radiographs in both mesial-distal and buccal-lingual views to minimize bias. Furthermore, the lengths of all the samples were standardized to 16 ± 1 mm and root canals were prepared up to master apical file F3 (#30/0.09).

Novel root canal filling materials have been introduced to improve the effectiveness of endodontic treatment; however, they must be easily removable when retreatment is needed.[9] In this study, the epoxy resin-based AH Plus sealer was chosen as a gold standard because of its extensive use in most of the studies for comparing with the tested sealers.

BioRoot RCS is a relatively new sealer with superior properties; however, limited studies are there for its retreatment. It is based on Active Biosilicate Technology and its bioactivity is reflected by mineralization of the dentinal structure and stimulating bone physiological process, thus providing a favourable environment for periapical healing[2,11] Furthermore, mineral infiltration zone formed by the precipitation of apatite as well as the cement plugs (up to 2000 μm) in the dentinal tubules, creates a unique chemical and micromechanical model of bonding that resists the dislocation of sealer from dentin.[12,13,14]

The root fillings were allowed to set for 3 weeks, to exclude the possibility of incompletely set sealer at the time of retreatment.

Various methods have been used in previous studies to assess the filling remnants such as radiographic examination, scanning electron microscopy,[15] confocal microscopy, optical microscopy, and stereomicroscopy or taking digital images after splitting teeth longitudinally.[16,17,18,19] The main drawback of these techniques is the loss of remnants during splitting with variation between different observers owing to subjective evaluation or underestimation of remnants as a result of two-dimensional imaging. Recently, micro-CT has been used in many of the studies[20] as it is nondestructible, repeatable, and can quantitatively measure the remnants with minimal operator control. Nevertheless, micro-CT is incongruous for clinical use and high-resolution CBCT imaging has been reported as a clinical alternative to micro-CT.

Various retreatment techniques have been described in the literature such as the use of the Gates Glidden drills, heat, or ultrasonic tips for the removal of the coronal obturation material.[17,18,19] These techniques were not implemented in the present study as their concurrent use could influence the results and be accountable for the confounding bias for the evaluation of the efficiency of the rotary retreatment files tested in this study. Rotary Ni-Ti systems are reported to be faster than hand instruments, thereby reducing patient and operator fatigue. This may be related to the heat produced due to frictional movement, which could plasticize the gutta-percha and facilitates its dissolution with easier removal along with less resistance.[19]

The efficacy of the PTUR file system for removing the obturating material has been comprehensively documented[21] and therefore used in the present study as standard.

Moreover, the file blades have a negative cutting angle with no radial land, thus, exerting a cutting and not a planning action on gutta-percha that may facilitate its easier removal.[22]

NeoEndo retreatment files have a heat-treated Ni-Ti metallurgy design having parallelogram cross-section, positive cutting edge with microgrinding manufacturing technology which limits the engagement zone. There is no literature review regarding the NeoEndo retreatment file; hence, the study was conducted with available data obtained from the manufacturer.

Reports on the effect of solvents on gutta-percha removal have been contradictory.[23] Horvath et al.[24] found that solvents resulted in more obturating remnants on the root canal surface because of its softening effect, resulting in the inadvertent distribution in the form of a film that is difficult to remove from the root canal walls.[23] Therefore, no solvent was used for retreatment in conjunction with the rotary retreatment files.

Regaining WL and patency in retreatment cases has been shown to substantially improve the periapical healing rates.[25] The present study reported re-establishment of WL in 100% of samples of BioRoot RCS retreated with NeoEndo Retreatment system but failed in 20% of the samples retreated with PTUR system. Furthermore, with BioRoot RCS, a higher frequency of failure was recorded in regaining apical patency irrespective of the retreatment technique used. This may be explained by the fact that files are unlikely to penetrate BCS because of the hardness upon the setting of bioceramics, but in some cases, the unset sealer may be penetrable. These findings are in accordance with the previous studies.[17]

Regardless of the technique used, the present study recorded greater remnants in the apical which may be explicated by the fact that both PTUR and NeoEndo-R system has a large taper, which is responsible for cutting more of coronal dentin. Furthermore, due to greater anatomical variations in the apical third region,[10,20] considerable enlargement is required for effective cleaning and shaping.

In the present study, straight root canals have retreated; therefore, the result of this study cannot be specifically applied to the teeth with complex root canal anatomy. Furthermore, in the present study, the preparation size of the primary treatment has not been increased following the removal of the obturation material which has been resulted in more volume percentage of the residual filling material in the apical sections. Thus, further studies are needed to evaluate the effect of canal re-instrumentation with larger sized instruments after retreatment procedure to obtain better apical cleaning.

CONCLUSION

The null hypothesis is rejected as no significant difference in filling remnants seen in root canals obturated with GP/Bioroot RCS and with GP/AH Plus sealer. The present study reported that the BioRoot RCS groups showed more filling remnants when retreated with PTUR system and least when retreated with NeoEndo Retreatment system. Furthermore, irrespective of the retreatment technique adopted, greater amounts of filling remnants persisted in the apical areas.

It can, therefore, be inferred that the novel BioRoot RCS can be considered to be manageable in a normal clinical setup. Furthermore, the NeoEndo Retreatment file system proves to be equally effective in the removal of BioRoot RCS with improved cyclic fatigue resistance and flexibility.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

I would like to acknowledge “Dr. Vikram Khanna,” Associate Professor, Oral Medicine and Radiology, Faculty of Dental Sciences, KGMC, Lucknow and “Dr. Vasu Siddharth Saxena,” Reader, Career Institute of Dental Sciences, Lucknow.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schirrmeister JF, Wrbas KT, Meyer KM, Altenburger MJ, Hellwig E. Efficacy of different rotary instruments for gutta-percha removal in root canal retreatment. J Endod. 2006;32:469–72. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dimitrova-Nakov S, Uzunoglu E, Ardila-Osorio H, Baudry A, Richard G, Kellermann O, Goldberg M. In vitro bioactivity of BiorootTM RCS, via A4 mouse pulpal stem cells. Dental Materials. 31;2;15:1290–7. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2015.08.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prüllage RK, Urban K, Schäfer E, Dammaschke T. Material properties of a tricalcium silicate-containing, a mineral trioxide aggregate-containing, and an Epoxy Resin-based Root Canal Sealer. J Endod. 2016;42:1784–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2016.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arias-Moliz MT, Camilleri J. The effect of the final irrigant on the antimicrobial activity of root canal sealers. J Dent. 2016;52:30–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Siqueira Zuolo A, Zuolo ML, Da Silveira Bueno CE, Chu R, Cunha RS. Evaluation of the efficacy of TRUShape and reciproc file systems in the removal of Root filling material: An ex vivo micro-computed tomographic study. J Endod. 2016;42:315–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stuart CH, Schwartz SA, Beeson TJ, Owatz CB. Enterococcus faecalis: Its role in root canal treatment failure and current concepts in retreatment. J Endod. 2006;32:93–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Somma F, Cammarota G, Plotino G, Grande NM, Pameijer CH. The effectiveness of manual and mechanical instrumentation for the retreatment of three different root canal filling materials. J Endod. 2008;34:466–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zanesco C, Prestes RG, Dotto RF, Geremia M, Fontanela VRC, Barletta FB. Effectiveness of ProTaper Universal® and D-RaCe® retreatment files in the removal of root canal filling material: An in-vitro study using digital subtraction radiography. Stomatos. 2014;20:42–50. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Good ML, McCammon A. An removal of gutta-percha and root canal sealer: A literature review and an audit comparing current practice in dental schools. Dent Update. 2012;39:703–8. doi: 10.12968/denu.2012.39.10.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Athkuri S, Mandava J, Chalasani U, Ravi RC, Munagapati VK, Chennareddy AR. Effect of different obturating techniques and sealers on the removal of filling materials during endodontic retreatment. J Conserv Dent. 2019;22:578–82. doi: 10.4103/JCD.JCD_241_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Camps J, Jeanneau C, El Ayachi I, Laurent P, About I. Bioactivity of a Calcium Silicate-based Endodontic Cement (BioRoot RCS): Interactions with human periodontal ligament cells in vitro. J Endod. 2015;41:1469–73. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagas E, Uyanik MO, Eymirli A, Cehreli ZC, Vallittu PK, Lassila LV, et al. Dentin moisture conditions affect the adhesion of root canal sealers. J Endod. 2012;38:240–4. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McMichael GE, Primus CM, Opperman LA. Dentinal tubule penetration of tricalcium silicate sealers. J Endod. 2016;42:632–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reyes-Carmona JF, Felippe MS, Felippe WT. The biomineralization ability of mineral trioxide aggregate and Portland cement on dentin enhances the push-out strength. J Endod. 2010;36:286–91. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kakoura F, Pantelidou O. Retreatability of root canals filled with Gutta percha and a novel bioceramic sealer: A scanning electron microscopy study. J Conserv Dent. 2018;21:632–6. doi: 10.4103/JCD.JCD_228_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ersev H, Yilmaz B, Dinçol ME, Daǧlaroǧlu R. The efficacy of ProTaper Universal rotary retreatment instrumentation to remove single gutta-percha cones cemented with several endodontic sealers. Int Endod J. 2012;45:756–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2012.02032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hess D, Solomon E, Spears R, He J. Retreatability of a bioceramic root canal sealing material. J Endod. 2011;37:1547–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim H, Kim E, Lee SJ, Shin SJ. Comparisons of the retreatment efficacy of calcium silicate and epoxy resin-based sealers and residual sealer in dentinal tubules. J Endod. 2015;41:2025–30. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2015.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simsek N, Keles A, Ahmetoglu F, Ocak MS, Yologlu S. Comparison of different retreatment techniques and root canal sealers: A scanning electron microscopic study. Braz Oral Res. 2014;28:S1806–83242014000100221. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107bor-2014.vol28.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Versiani MA, Pécora JD, de Sousa-Neto MD. Flat-oval root canal preparation with self-adjusting file instrument: A micro-computed tomography study. J Endod. 2011;37:1002–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gu LS, Ling JQ, Wei X, Huang XY. Efficacy of ProTaper Universal rotary retreatment system for gutta-percha removal from root canals. Int Endod J. 2008;41:288–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rios Mde A, Villela AM, Cunha RS, Velasco RC, De Martin AS, Kato AS, et al. Efficacy of 2 reciprocating systems compared with a rotary retreatment system for gutta-percha removal. J Endod. 2014;40:543–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilcox LR, Krell KV, Madison S, Rittman B. Endodontic retreatment: Evaluation of gutta-percha and sealer removal and canal reinstrumentation. J Endod. 1987;13:453–7. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(87)80064-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horvath SD, Altenburger MJ, Naumann M, Wolkewitz M, Schirrmeister JF. Cleanliness of dentinal tubules following gutta-percha removal with and without solvents: A scanning electron microscope study. Int Endod J. 2009;42:1032–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2009.01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ng YL, Mann V, Gulabivala K. A prospective study of the factors affecting outcomes of nonsurgical root canal treatment: Part 1: Periapical health. Int Endod J. 2011;44:583–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]