Abstract

The biomolecular modeling field has flourished since its early days in the 1970s due to the rapid adaptation and tailoring of state-of-the-art technology. The resulting dramatic increase in size and timespan of biomolecular simulations has outpaced Moore’s law. Here, we discuss the role of knowledge-based versus physics-based methods and hardware versus software advances in propelling the field forward. This rapid adaptation and outreach suggests a bright future for modeling, where theory, experimentation and simulation define three pillars needed to address future scientific and biomedical challenges.

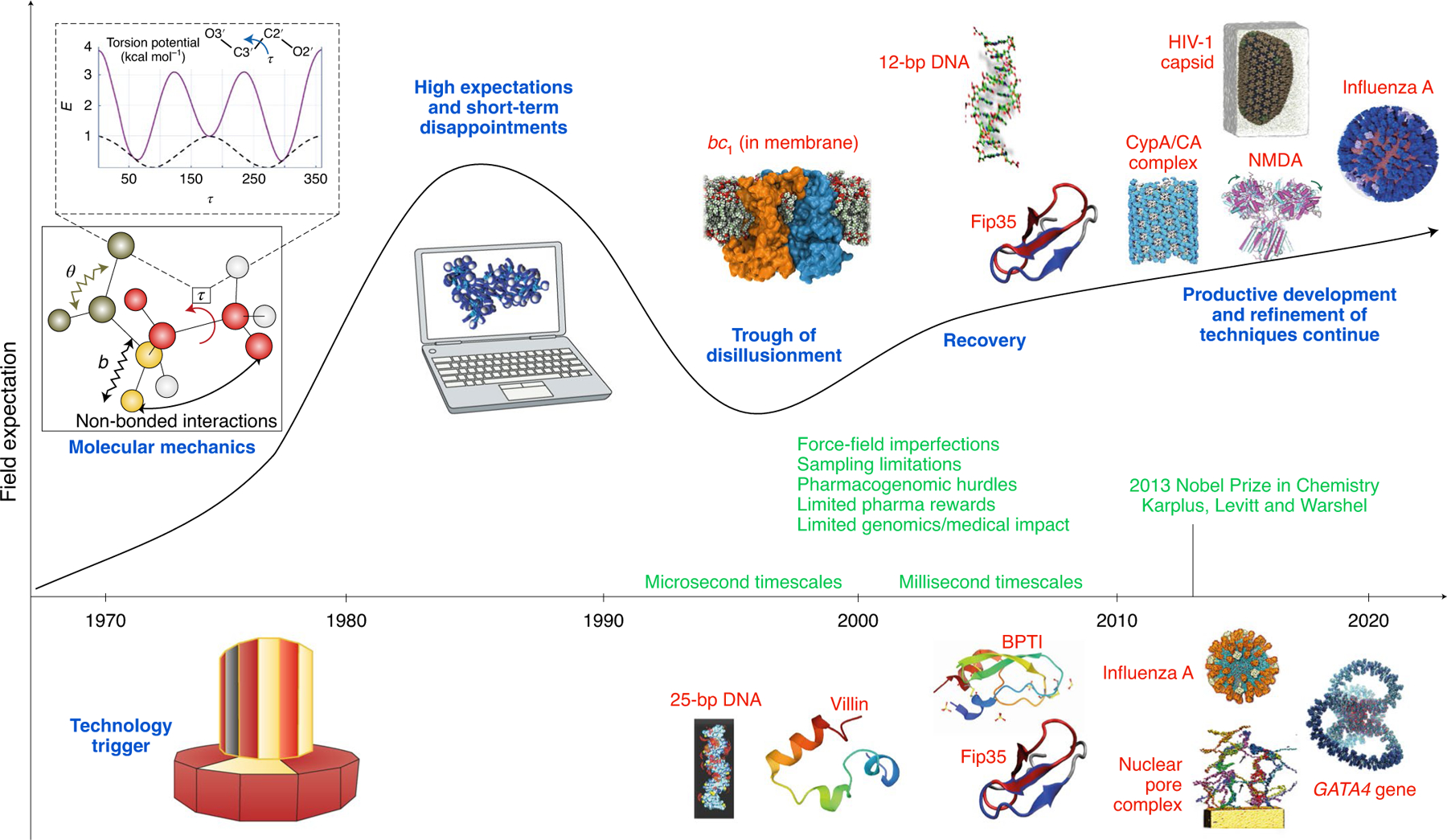

The trajectory of the field of biomolecular modeling and simulation is a classic example of success driven by an eclectic mixture of ideas, people, technology and serendipity. From the early days of simulations and force-field development through pioneering applications to structure determination, enzyme kinetics and molecular dynamics simulations, the field has gone through notable highs and lows1 (Fig. 1). The 1980s were marked by advances made possible by supercomputers2,3, and, at the same time, by deflated high expectations when it was realized that computations could not easily or quickly supplant Bunsen burners and lab experiments1,4. The 1990s saw disappointments when, in addition to unmet high biomedical expectations1, such as the failure of the human genome information to lead quickly to medical solutions5, it was realized that force fields and limited conformational sampling could hold us back from successful practical applications. Fortunately, this period was followed by many new approaches, using both software and hardware, to address these deficiencies. The past two decades took us through huge triumphs, as successes in key areas were realized. These include protein folding (for example, millisecond all-atom simulations of protein folding6), mechanisms of large biomolecular networks (for example, virus simulations7) and drug applications (for example, search of drugs for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)8). On the shoulders of the force-field pioneers Allinger, Lifson, Scheraga and Kollman, computations in biology were celebrated in 2013 with the Nobel Prize in Chemistry recognizing the work of Martin Karplus, Michael Levitt and Arieh Warshel9. Clearly, experimentation and modeling have become full partners in a vibrant and successful field.

Fig. 1 |. Expectation curve for the field of biomolecular modeling and simulation.

The field started with comprehensive molecular mechanics efforts, and it took off with the increasing availability of fast workstations and later supercomputers. In the molecular mechanics illustration (top left panel), symbols b, θ and τ represent bond, angle and dihedral angle motions, respectively, and non-bonded interactions are also indicated. The torsion potential (E) contains two-fold (dashed black curve) and three-fold (solid violet curve) terms. Following unrealistically high short-term expectations and disappointments concerning the limited medical impact of modeling and genomic research on human disease treatment, better collaborations between theory and experiment has ushered the field to its productive stage. Challenges faced in the decade 2000–2010 include force-field imperfections, conformational sampling limitations, some pharmacogenomics hurdles and limited medical impact of genomics-based therapeutics for human diseases. Technological innovations that have helped drive the field include distributed computations and the advent of the use of GPUs for biomolecular computations. The molecular-dynamics-specialized supercomputer Anton made it possible in 2009 to reach the millisecond timescale for explicit-solvent all-atom simulations. The 2013 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded to Levitt, Karplus and Warshel helped validate a field that lagged behind experiment and propel its trajectory. Along the timeline, we depict landmark simulations: 25-bp DNA (5 ns and ~21,000 atoms)144; villin protein (1 μs and 12,000 atoms)145; bc1 membrane complex (1 ns and ~91,000 atoms)146; 12-bp DNA (1.2 μs and ~16,000 atoms)147; Fip35 protein (10 μs and ~30,000 atoms)148 (image from149); Fip35 and bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitory (BPTI) proteins (100 μs for Flip35 and 1 ms for BPTI, and ~13,000 atoms)150; nuclear pore complex (1 μs and 15.5 million atoms)151; influenza A virus (1 μs and >1 million atoms)152; N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor in membrane (60 μs and ~507,000 atoms)153; tubular cyclophilin A/capsid protein (CypA/CA) complexes (100 ns and 25.6 million atoms)154; HIV-1 fully solvated empty capsid (1 μs and 64 million atoms)7; GATA4 gene (1 ns and 1B atoms)39; and influenza A virus H1N1 (121 ns and ~160 million atoms)36. Figure adapted with permission from ref.1, Cambridge Univ. Press.

Scientists studying chemical and biological systems, from small molecules to huge viruses, now routinely combine computer simulations and a variety of experimental information to determine or predict structures, energies, kinetics, mechanisms and functions of these fascinating and important systems. Pioneers and leaders of the field who pushed the envelopes of applications and technologies through large simulation programs and state-of-the-art methodologies have unveiled the molecules of life in action, similar to what the light microscopes and X-ray techniques did in the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. Biomolecular modeling and simulation applications have allowed us to pose and answer new questions and pursue difficult challenges, in both basic and applied research. Problems range from unraveling the folding pathways of proteins and identification of new therapeutic targets for common human diseases to the design of novel materials and pharmaceuticals. With the recent emergence of the coronavirus pandemic, all these tools are being utilized in numerous community efforts for simulating COVID-19 related systems. Similar to the exponential growth so familiar to us now in connection with the spread of COVID-19 infections, exponential progress is only realized when we take stock of long timeframes.

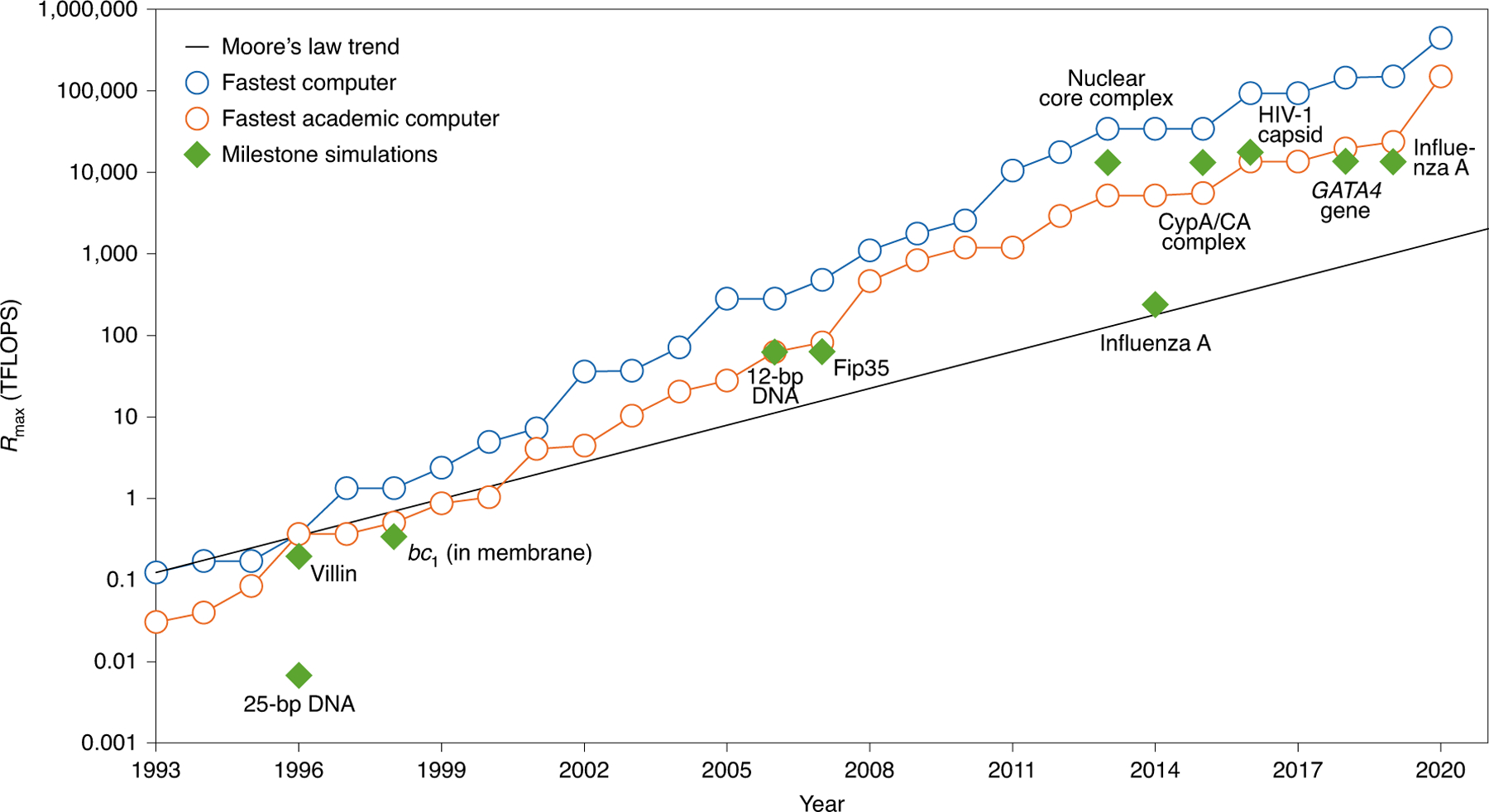

A key element in this success is the relentless pursuit and exploitation of the state-of-the-art technology by the biomolecular simulation community. In fact, the excellent utilization of supercomputers and technology by modelers led to comparable performance for landmark simulations with the world’s fastest computers (Fig. 2). The simulation time of biomolecular complexes scales up by about three orders of magnitude every decade10, and this progress is faster than Moore’s law, which projected a doubling every two years11. While some aspects of this doubling have been debated, it has also been argued that such doubling of computation/performance has held over 100 years in many fields12.

Fig. 2 |. Performance of landmark simulations compared with the world’s fastest supercomputers and moore’s law trend.

Plot of the computational system ranked first (blue) and the highest ranked academic computer (orange) as reported in Rmax according to the LINPACK benchmark as assembled in the Top500 supercomputer lists (www.top500.org). Rmax is the unit used to define computer performance in TFLOPS (trillion floating point operations per second). Landmark simulations (green diamonds) are dated assuming calculations were performed about a year before publication, except for the publications in 1998, which we assumed were performed in 1996. These include, from 1996 to the present, 25-bp DNA using National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) Silicon Graphics Inc. (SGI) machines144; villin protein145 using the Cray T3E900; bc1 membrane complex146 using the Cray T3E900; 12-bp DNA147 using MareNostrum/Barcelona; Fip35 protein148 using NCSA Abe clusters; nuclear core complex151 using Blue Waters; influenza A virus152 using the Jade Supercomputer; CypA/CA complex154 using Blue Waters; HIV-1 capsid7 using Titan Cray XK7; GATA4 gene39 using Trinity Phase 2; and influenza A virus H1N136 using Blue Waters. As Blue Waters has opted out of the Top500, we use estimates of sustained system performance/sustained petascale performance (SSP/SPP) from 2012 and 2020. For system size and simulation time of each landmark simulation, see Fig. 1.

Today, concurrent advances in many technological fields have led to exponential growth in allied fields. Take, for example, the dramatic drop in the cost of gene sequencing technology, from US$2.7 billion for the Human Genome Project to US$1,000 today to sequence an individual’s genome13. Not only can this information be used for personalized medicine, but we can also sequence genomes such as of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in hours and apply such sequence variant information to map the disease spread across the world in nearly real time14. Fields such as artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, energy and robotics are all benefiting from exponential growth as well. This in turn means that urgent problems can be solved to improve our lives, health and environment, from wind farms to vaccines. In particular, biomolecular modeling and simulation is thriving in this ever-evolving landscape, evidenced by many successes, and in experiments driven by modeling15.

A detailed account of this triumphant field trajectory is described separately in our recent field perspective1. A review on the success of computations in this field was also recently published by Dill et al.16. In our field perspective, we covered metrics of the field’s rise in popularity and productivity, examples of success and failure, collaborations between experimentalists and modelers, and the impact of community initiatives and exercises. Here, we focus on two aspects of technology advances that are relevant to numerous areas of computational science at large: knowledge-based methods versus physics-based methods, and the role of hardware versus software in driving the field.

Knowledge-based versus physics-based approaches

Physics-type models based on molecular mechanics principles1 have been successfully applied to molecular systems since the 1960s, providing insights into structures and mechanisms involved in biomolecular rearrangements, flexibility, pathways and function. In these methods, energy functions that treat molecules as physical systems, similar to balls connected by springs, are used to express biomolecules in terms of fundamental vibrations, rotations and non-bonded interactions. Target data taken from experiments on relevant molecular entities are used to parametrize these functions, which are then applied to larger systems composed of the same basic chemical subgroups. Thus, experimental data are used in constructing these general functions but in a fundamental way, such as the nature of C–O bonds or the rotational flexibility around alpha carbons.

Knowledge-based methods, in contrast, lack a fundamental energy framework. Instead, various structural, energetic or functional data are used to train a computer program into discovering these trends in related systems from known chemical and biophysical information on specific molecular systems. Thus, such approaches use available data to make extrapolative predictions regarding related biological and chemical systems.

While physics-based models have been in continuous usage, knowledge-based methods have gained momentum since the 2000s with the increasing amount of both available data and computational power for handling voluminous data. Although physics-based approaches remain essential for understanding mechanisms, knowledge-based methods are inevitably succeeding in specific applications and overtaking many fields of science and engineering. As we argue below, both are important to develop, and their combination can be particularly fruitful.

Physics-based methods.

Physics-based methods offer us a conceptual understanding of biological processes. Indeed, the development of improved all-atom force fields for biomolecular simulations17–19 in both functional form and parameters has been crucial to the increasing accuracy of modeling many biological processes of large systems. Force fields for proteins, nucleic acids, membranes and small organic molecules have been applied to study problems such as protein folding, enzymatic mechanisms, ligand binding/unbinding, membrane insertion mechanisms and many others20,21. Current fourth-generation force fields have introduced polarization effects22–24, important for processes or systems with induced electronic polarization, such as intrinsically disordered proteins, metal/protein interactions and membrane permeation mechanisms25,26. Despite 50 years of developments, force fields are far from perfect27, and further refinement, expansion, standardization and validation can be expected in the future28. Transferability to a wide range of biomolecular systems and ‘convergence’ among different force fields will continue to be issues. In parallel to all-atom force fields, numerous coarse-grained potentials have been developed for many systems29,30, but these are far less unified compared with all-atom force fields. Much development can be expected in the near future in this area as the complexity of biomolecular problems of interest increases.

In the area of protein structure prediction, for example, the physics-based coarse-grained united-residue (UNRES) force field developed by the lab of the late Harold Scheraga demonstrated exceptional results in predicting the orientations of domains in the tenth Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction (CASP10)31. Such predictions were free of biases from structural databases and relied on energetically favorable residue/residue interactions (‘first principles’).

Physics-based methods are essential for studying protein dynamics and folding pathways. For example, UNRES32 and many all-atom force fields17–19 have been successful in the study of folding pathways of several proteins33,34, including a small protein inside its chaperonin35. Besides folding mechanisms, kinetic and thermodynamic parameters can be determined33.

Many other areas of applications demonstrate how molecular mechanics and dynamics simulations provide insights on structures and mechanisms. These include structures of viruses7,36 (including SARS-CoV-237), pathways in DNA repair38 or folding of chromatin fibers39–41. In drug discovery, molecular docking has shown to be successful for high-throughput screening. For instance, restrained-temperature multiple-copy molecular dynamics (MD) replica-exchange combined with molecular docking suggested molecules that bind to the spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2 virus42.

The most common concerns in such molecular mechanics approaches involve insufficient conformational sampling and limited simulation length compared with biological timeframes. Other drawbacks are approximations due to force-field imperfections and other model simplifications, absence of adequate statistical information and the lack of general applicability to all molecular systems43. Increases in computer power, advances in enhanced simulation techniques and fourth-generation force fields with incorporated polarizabilities22–24 are helping overcome these limitations. For example, the Frontera petascale computing system allowed multiple microsecond all-atom MD simulations of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein embedded in the viral membrane44. Enhanced sampling simulations combining parallel tempering with well-tempered ensemble metadynamics revealed how phosphorylation of intrinsically disordered proteins regulates their binding to their interacting partners45. The polarizable force-field AMOEBA has allowed the determination of the phosphate binding mode to the phosphate binding protein46, which has remained controversial for a long time.

Knowledge-based methods.

Knowledge-based methods are less conceptually demanding than physics-based models and can in principle overcome the approximations of physics-based methods.

In the field of protein folding and structure prediction, knowledge-based methods, such as homology47, threading48 and minithreading modeling49 have shown to be more effective than physics-based methods in some cases50. Other successful algorithms use information on evolutionary coupled residues, namely, residues involved in compensatory mutations51. Such information can be detected from multiple sequence alignments and used to predict protein structures de novo with high accuracy, as observed in CASP11.52

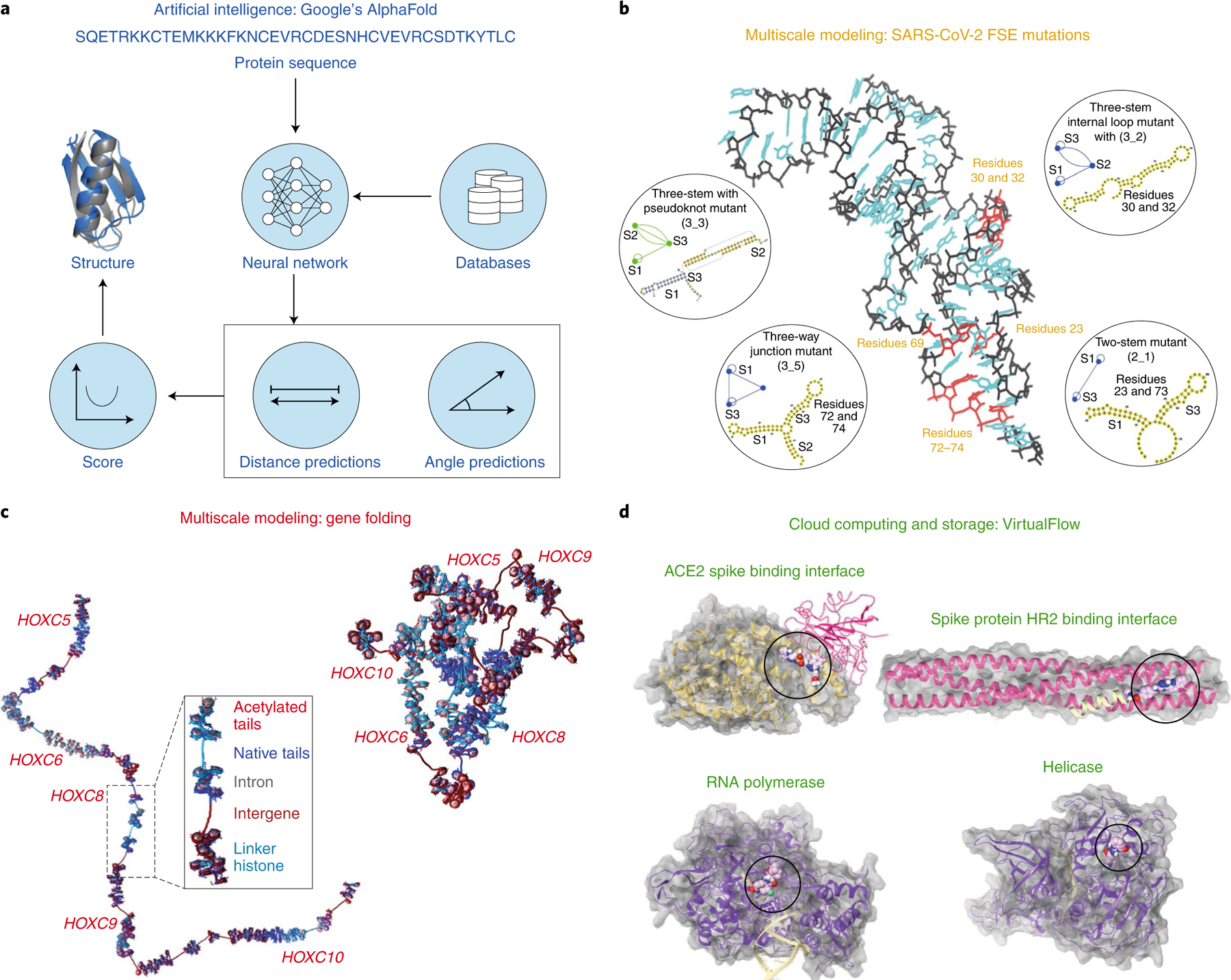

In particular, the artificial intelligence approach by Google AlphaFold, a co-evolution-based method, upstaged the CASP13 exercise held in 2018, outperforming other methods for protein structure prediction53 (Fig. 3a). More recently, analyses of CASP14 (2020) results with the updated AlphaFold2 revealed unprecedented levels of accuracy across all targets54.

Fig. 3 |. Applications of biomolecular modeling made possible by technology advances.

a, AlphaFold workflow. Deep neural networks are trained with known structures deposited in the Protein Data Bank to predict protein structures de novo155. The distribution of distances and angles are obtained and then the scores are optimized with gradient descent to improve the designs. b, RNA mesoscale modeling. Target residues for drugs or gene editing in SARS-2-CoV frameshifting element (FSE) identified by graph theory combined with all-atom microsecond MD simulations made possible by a new four-petaflop ‘Greene’ supercomputer at New York University. c, Chromatin mesoscale modeling. HOXC mesoscale model at nucleosome resolution constructed with experimental information on nucleosome positioning, histone tail acetylation and linker histone binding130. Shown is the unfolded gene (left) and the folded structure of the gene (right). d, Cloud computing. Targeted protein sites related to SARS-CoV-2 with bound ligands from the billion compound database screened with VirtualFlow platform that makes use of cloud computing and cloud storage156. Figure reproduced with permission from: a, ref.157, Springer Nature America, Inc. (structure image); b, ref.119, Cell Press; c, ref.130, PNAS; d, https://vf4covid19.hms.harvard.edu, Harvard Univ. See original works for full names and abbreviations.

The increasing amount of high-resolution structural data for protein/ligand binding, as deposited in the Protein Data Bank, has accelerated the use of knowledge-based methods in drug discovery, a key application of biomolecular modeling. For example, the crystal structure of the main protease of the SARS-CoV-2 virus was solved unliganded and in complex with a peptide mimetic inhibitor55, providing the basis for the development of improved inhibitors using knowledge-based methods56. Also related to COVID-19, artificial intelligence tools have been used to identify potential drugs against SARS-CoV-257.

Of course, the accuracy of knowledge-based methods depends on the quality and size of the database available, similarity between the underlying database and the systems studied, and the analysis methods applied. Even in large databases, some systems are underrepresented. These include, for example, RNAs with higher-order junctions58, where few experimental data exist, and intrinsically disordered proteins, which are difficult to solve by conventional X-ray or NMR techniques. Such problems may be alleviated in principle as more data become available. Nonetheless, unbalanced databases can produce erroneous results. For example, models trained with databases of ligand–protein complexes where ligands that bind weakly are underrepresented59,60 can overestimate binding affinities.

For some applications, such as deriving force fields by machine learning protocols, access to a large and diverse high-quality training dataset obtained by quantum mechanics calculations is essential to obtain reliable results for general applications61. However, there are no known criteria of sufficiency. How many molecular descriptors are required to satisfactorily explain ligand binding or chemical reactivity? How many large non-coding RNAs are diverse enough to represent the universe of RNA folds for these systems?

Combined knowledge and physics-based methods.

Fortunately, combinations of knowledge and physics-based approaches can merge the strengths of each technique, integrating specific molecular information with learned patterns. For instance, maximum entropy62 and Bayesian63 approaches integrate simulations with experimental data. They generate structural ensembles for the systems using MD or Monte Carlo simulations and incorporate them by imposing restraints to reproduce experimental data.

Protein-folding approaches can be improved by the use of hybrid energy functions that combine physics-based with knowledge-based components. For example, physics-based functions can be modified with structural restraints from NMR experiments49, torsion angle correction terms for the backbone or side chains of residues64 or hydrogen-bonding potentials based on high-resolution protein crystal structures65.

In protein structure refinement, combinations of physics-based and knowledge-based approaches have shown to be particularly successful. For example, in the CASP10 exercise, MD simulations from the Shaw66 and Zhang67 groups showed that experimental constraints were crucial for refining predicted structures. Pure physics-based methods were unsuccessful at correcting non-native conformations toward native states. Recently, it was reported that refinements with MD simulations of models obtained with AlphaFold substantially improve the predicted structures68.

In computer-aided drug design, quantitative structure/property relationship (QSPR) models combine experimental and quantum mechanical descriptors to improve the prediction of Gibbs free energies of solvation69. MD simulations combined with machine learning algorithms can help create improved quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) models70.

In the long run, inferring mechanisms is critical for understanding and addressing complex problems in biophysics. Force fields will not likely disappear any time soon, despite the growing success of knowledge-based methods. As shown in public citizen projects, such as Foldit for protein folding71, combinations of both physics-based and knowledge-based methods will probably work best. Importantly, human intuition and insight is needed to fully merge both approaches and properly interpret the computational findings.

The role of algorithms versus hardware

Rigorous and efficient algorithms are essential for the success of any biomolecular modeling or simulation. New algorithms are required to address problems as they emerge, as well as to utilize new technologies and hardware developments. Classic examples of algorithms that enhanced the reliability and efficiency of biomolecular simulations include the particle-mesh Ewald method for treatment of electrostatics72 and symplectic and resonance-free methods for long-time integration1,73–75 in MD simulations. Hardware advances, in addition, are essential for expanding system size and simulation timeframes. The continuing increase in computer power, in combination with parallel computing, has been crucial in the development of the field of biomolecular simulations. Both hardware and software will be essential to the continued success of the field.

Algorithms and software advances.

Outstanding progress has been reported in developing software to enhance sampling, reduce computational cost and integrate information from machine learning and artificial intelligence methods to solve biological problems. Algorithms that utilize novel hardware such as graphics processing units (GPUs) and coupled processors have also been impactful. Enhanced sampling methods and particle-based methods such as Ewald summations have revolutionized how molecular simulations are performed and how conformational transitions can be captured, for example, to connect experimental endpoints76. MD algorithms such as multiple timestep approaches, in contrast, have achieved far less impact than hardware innovations, due to a relatively small net computational gain. However, their framework may be useful in combination with other improvements such as enhanced sampling algorithms77 or optimized particle-mesh Ewald algorithms78. The complexity and size of the biological systems of interest increases every year and thus continued algorithm development is crucial to obtain reliable methods that balance accuracy and performance.

Density functional theory (DFT)79,80, used in quantum mechanical (QM) applications since the 1990s, has become one of the most popular QM methods to study biomolecules. DFT has a computational cost similar to semi-empirical methods but higher accuracy. New DFT functionals are continuously being developed to improve the description of dispersion and for special applications81. The high efficiency of DFT implies that larger and more complex systems can be studied, expanding the applications and predictive power of electronic structure theory, and promoting collaborations between modelers and experimentalists82. This high efficiency has also been exploited by MD methods; DFT-based MD simulation methods, such as Car–Parrinello MD83 and ab initio MD84, are widely applied to study electronic processes in biological systems, such as chemical reactions85.

Because of the computational cost of QM methods and the large size of most biological systems, the development of combined quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) methods was fundamental to advance electronic structure calculations of biological systems86. In particular, computational enzymology has driven the development of these methods since the pioneering work of Warshel and Levitt on the reaction mechanism of the lysozyme87. By partitioning the system into an electronic active region and the rest, which is treated at a molecular mechanical level, computational effort is centered in the part of the system where it is needed, and the overall cost is substantially reduced. Nowadays, several QM/MM methods differing in the scheme used to compute QM/MM energies, the treatment of the boundary region and the QM to MM interactions are applied to study many enzymatic mechanisms, metal–protein interactions, photochemical processes and redox processes, among others86,88,89. Adaptive QM/MM methods that reassign the QM and MM regions on the fly have also been developed90. These methods are particularly important to study ions in solution or in biomolecules, and chemical reactions in explicit solvent.

Recent QM/MM methods employ machine learning (ML) potentials in place of MM calculations91. Such QM/ML schemes can avoid problems associated with force fields as well as boundary issues between the QM and MM regions. Other recent developments use neural networks coupled with QM/MM algorithms; the neural networks are used to predict potential energy surfaces at an ab initio/MM level from semi-empirical/MM calculations92.

Many of the biological processes of interest occur on timescales that are not easily accessible by conventional MD simulations. Thus, a variety of enhanced sampling algorithms have been developed93,94. These methods improve the sampling efficiency by reducing energy barriers and allowing the systems to escape local minima in the potential energy surface. Speedups compared with conventional MD can be around one order of magnitude or more95. Methods based on collective variables such as umbrella sampling96, metadynamics97 and steered MD98 have advanced the field with applications to ligand binding/unbinding, conformational changes of proteins and nucleic acids, free energy profiles along enzymatic reactions and ligand unbinding, and protein folding. Methods that do not require definition of specific collective variables or reaction coordinates, such as replica exchange MD99 and accelerated MD100 have shown to be particularly successful when defining a collective variable is difficult, for example, when exploring transition pathways and intermediate states. Markov state models (MSMs) can help describe pathways between different relevant metastable states identified by experiments or MD. For example, when studying the folding of a dimeric protein101, an MSM of the metastable states on the free-energy surface has identified the states that describe the folding process, as well as the specific inter-residue interactions that can lead to kinetic traps. Physics-based protein folding has benefited from the application of MSMs that combine many short independent trajectories102,103. Related thermodynamic integration104 and free-energy perturbation105 methods, which calculate free-energy differences between initial and final states, have also helped determine protein/ligand binding constants, membrane/water partition coefficients, pKa values and folding free energies106,107 to connect simulations to experimental measurements.

Enhanced sampling techniques are now being combined with machine learning to improve the selection of collective variables108 and to develop new methods109,110. Clearly, artificial intelligence and ML algorithms are changing the way we do molecular modeling. Coupled with the growth of data, GPU-accelerated scientific computing and physics-based techniques, these algorithms are revolutionizing the field. Since the pioneering work of Behler and Parrinello on the use of neural networks to represent DFT potential energy surfaces and thus to describe chemical processes111, ML has been applied to design all-atom and coarse-grained force fields, analyze MD simulations, develop enhanced sampling techniques and construct MSMs, among others112. As discussed above, Google’s AlphaFold performance in CASP13 and CASP14 showed how impactful these kinds of algorithms can be for predicting protein structure53,54. Artificial intelligence platforms for drug discovery have also led to clinical trials for COVID-19 treatments in record times57.

Multiscale models.

A special case of algorithms that has potential to revolutionize the field involves multiscale models. Crucial for bridging the gap between experimental and computational timeframes, such models increase spatial and temporal resolution by use of coarse graining, interpolation and other ways to connect all the information on different levels.

The 2013 Nobel Prize in Chemistry that recognized Karplus, Levitt and Warshel for their work on developing multiscale models has underscored the importance of these models. In the 1970s, bridging molecular mechanics with quantum mechanics defined indeed a new way of simulating molecular systems113. The first hybrid model of this type by Warshel and Karplus113 was initially intended to study chemical properties and reactions of planar molecules but was later extended to study enzymatic reactions87. Today’s models are numerous and varied. While useful in practice, they are generally tailored to specific systems and lack a rigorous theoretical framework.

For example, numerous coarse-grained protein models have been developed and applied to protein dynamics, folding and flexibility, protein structure prediction, protein interactions and membrane proteins, as recently reviewed114.

Coarse-grained models have also been developed to study nucleic acids. Possibly due to small volumes of structural data, high charge density and wide structural diversity, they have progressed somewhat slower than for proteins, especially in the case of RNA.

DNA coarse-grained models allow us to study, in reasonable time, large DNA systems that could not be approached by all-atom models. The reduction in the degrees of freedom achieved by coarse-grained models has allowed the study of thousands of base pair systems in scales of microseconds to milliseconds. Crucial studies include self-assemblies of large DNA molecules, the denaturalization process, the hybridization process important for many biological functions, the topology of DNA mini-circles and the sequence-dependence of single-stranded DNA structures29,115,116.

The flexibility of RNAs and the huge spectrum of possible conformations make their modeling challenging, and numerous coarse-grained models that differ in the number of beads per nucleotide and interactions included in the model and their treatment have been developed117,118. A different coarse-grained approach using two-dimensional and three-dimensional graphs to represent RNA structure has also proven useful to analyze and design novel RNAs, including the SARS-CoV-2 frameshifting element119 (Fig. 3b).

Coarse-grained models have also been applied to biomembranes, systems of thousands of lipids that undergo large-scale transitions in the microsecond-to-millisecond regime120–122. Membrane protein dynamics, virion capsid assembly, lipid recognition by proteins and many remodeling processes have been successfully captured in such coarse-grained applications121.

Finally, to study DNA complexed with proteins, such as in the context of chromatin fibers, multiscale approaches are essential, as recently reviewed123,124. These approaches derive the chromatin model from the atomistic DNA, nucleosomes and linker histones. Successful models by the groups of the late Langowski41, Wedemann125, Nordenskiöld126, Olson127, Spakowitz128, de Pablo129 and ours40,123 have been applied to understand the mechanisms that regulate chromatin compaction and function. For example, our recent three-dimensional folding of the HOXC gene cluster (~55 kbp) at nucleosome resolution by mesoscale modeling130 revealed how epigenetic factors act together to regulate chromatin folding (Fig. 3c). The next challenge for these types of model is to merge the kilobase to megabase levels of understanding chromatin while retaining a basic dependency on the physical parameters that dictate fiber conformations.

Multiscale models are as much art as science, as they require subjective decisions on what parts to approximate and what parts to resolve. Yet much information guides these models, and important biological problems serve as motivators. Overall, innovative advances in both algorithms and hardware, especially in multiscale modeling, will be pivotal for the progress of the biological sciences in the coming years.

Hardware advances.

The computational biology and chemistry communities have utilized hardware exceptionally well. This is evident from the expectation curve in Fig. 1 and from the computer technology plot in Fig. 2. We see that hardware innovations have propelled the field of biomolecular simulations forward by around six orders of magnitude over three decades as reflected by simulation length and size of biomolecular systems.

In the first decade of the twenty-first century, hardware innovations such as the supercomputers Anton and Blue Waters propelled the field by expanding the limits of both system size and simulation time that is possible. Today, nanosecond simulations of a 160-million-atom influenza virus36 or the 1-billion-atom GATA4 gene39 have become possible.

At the same time, the introduction of GPUs for biomolecular simulations by NVIDIA broke new grounds. GPUs are specialized electronic circuits designed to rapidly manipulate and alter memory to accelerate computations. Such GPUs contain hundreds of arithmetic units and possess a high degree of parallelism, allowing performance levels tens or hundreds of times higher than a single central processing unit (CPU) core with tailored software131.

The acceleration of MD simulations by GPU computing and supercomputers substantially reduced the gap between experimental and theoretical scales. For example, as mentioned above, the world’s second-fastest supercomputer—Summit from the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, with more than 27,000 NVIDIA GPUs and 9,000 IBM Power9 CPUs—was used to explore SARS-CoV-2 virus inhibitors among more than 8,000 compounds42. Such simulations were conducted in just a few days, with 77 compound candidates found. GPU-based algorithms for free-energy calculations can achieve a speedup of 200 compared with CPU-based methods132. QM/MM GPU-based methods have also accelerated calculations focused on enzymatic mechanisms. For example, GPU-based DFT in the framework of hybrid QM/MM calculations such as ONIOM133 or additive QM/MM134 realize speedup factors of 20 to 30 compared with CPU-based calculations. The Folding@home distributed computing project, dedicated to understanding the role of protein folding in several diseases, is conducting most calculations on GPUs by using simulation packages adapted to this architecture135. Recently, over a million citizen scientists helped solve COVID-19 challenges; they combined ~280,000 GPUs, reaching the exascale and generating more than 0.1 s of simulation136. These simulations helped understand how the SARS-CoV-2 virus spike surface protein attaches to the receptors in human cells. MD software adapted to GPU-accelerated architectures is also being used to perform enormous cell-scale simulations137, important to mimic realistic cellular environments and to study viral and bacterial infections.

Cloud-based computing is surging as a viable alternative to supercomputers, providing researchers with remote high-performance computing platforms for large-scale simulations, analysis and visualization. Acquisition and maintenance of such hardware is not affordable for individual research groups, but feasible for institutions and companies. For example, Google’s Exacycle has been used to conduct millisecond simulations of the G-protein-coupled receptor β2AR that revealed its activation pathway, important for the design of drugs to treat heart diseases138. Recently, in an unprecedented study, the Google Cloud Platform and Google Cloud Storage were combined to screen around 1 billion compounds against 15 SARS-CoV-2 proteins and 2 human proteins involved in the infection139 (Fig. 3d). A high-performance version of the popular visualization program VMD has been implemented on the Amazon cloud140, as well as the MD toolkit QwikMD141 and the molecular dynamics flexible fitting (MDFF) method for structure refinement from cryo-electron microscopy densities142. These efforts allow scientists worldwide to access powerful computational equipment and software packages in a cost-effective way.

Overall, tailored computers for molecular simulations, such as Anton, can accelerate the calculation of computationally expensive interactions with specialized software143, while general-purpose supercomputers or cloud computing that parallelize MD calculations across multiple processors with thousands of GPUs or CPUs can accelerate performance (for example, trillions of calculations per second) for large systems36,39.

Although hardware advances have overwhelmed software advances, both are clearly needed for optimal performance. Hardware bottlenecks will inevitably emerge as computer storage limits are reached. Yet, whether or not Moore’s law will continue to be realized11, software advances will always be important. Certainly, engineers and mathematicians will not be out of jobs.

Figure 4 summarizes key software, hardware and algorithm developments that helped breakthrough studies.

Fig. 4 |. Key developments in algorithms, software and hardware that advanced the field.

1970s: simulations of <1,000-atom systems and few picoseconds in vacuo were possible due to the development of digital computers and algorithms to treat long-range Coulomb interactions. The image depicts the structure of the small protein BPTI that was simulated for 8.8 ps without hydrogen atoms and with four water molecules158. 1980s: simulations that considered solvent effects became possible, and algorithms such as SHAKE, to constrain covalent bonds involving hydrogen atoms, allowed the study of systems with explicit hydrogens. The image depicts the 125 ps simulation of the 12 bp DNA in complex with the lac repressor protein159 in aqueous solution using the simple three-point charge water model. 1990s: QM/MM methods can perform geometry optimizations, MD and Monte Carlo simulations160. The image depicts the acetyl-CoA enolization mechanism by the citrate synthase enzyme studied with AM1/CHARMM. 2000s: GPU-based MD simulations, specialized supercomputers such as Anton, shared resources such as Folding@home, enhanced sampling algorithms and Markov state models (MSMs) all contributed to advance protein folding161. The image depicts the long 100 μs simulation of the Fip35 folding conducted in Anton (red) compared with the X-ray structure (blue). 2010s: all-atom and coarse-grained MD simulations of viruses performed on supercomputers such as Blue Waters became common162. The image depicts the MD simulation of the all-atom HIV capsid using the MDFF method that uses cryo-electron microscopy data to guide simulations. 2020s: physical whole-cell models are being developed to fully understand how biomolecules behave inside cells and to study interactions between them, for example, within viruses and cells. The image depicts the model of the interaction between the spike protein in the SARS-CoV-2 surface and the ACE2 receptor on a human cell surface being developed in the Amaro Lab. From left to right, images adapted with permission from: (left to right); second image, ref.159, Wiley; third image, ref.163, Wiley; fourth image, ref.150, AAAS; fifth image, ref.164, Springer Nature Ltd; sixth image, https://amarolab.ucsd.edu/news.php, Amaro Lab.

Conclusions and outlook

Technology has driven many advances that affect our everyday life, from cellphones and personal medical devices, to solar energy and coping in times of physical isolation during the current COVID-19 pandemic. Biomolecular modelers have consistently leveraged technology to solve important practical problems efficiently and will undoubtedly continue to do so. Machine learning and other data science approaches are now offering new tools for discovery in numerous fields. These tools for predicting structures, dynamics and functions of biomolecules can be combined with physics-based approaches not only to find solutions but also to understand associated mechanisms. Algorithms such as MSMs, neural networks, multiscale modeling, enhanced conformational sampling and comparative modeling can be leveraged as never before, especially in combination with these data-science approaches.

We expect that force-field based methods will remain essential for the understanding of mechanisms of biomolecular systems, but knowledge-based methods will certainly gain momentum. Although the recent breathtaking results from AlphaFold254 might tempt us to believe that the physics-based era is over, the range of complex problems beyond protein folding is unlikely to be easily solved by knowledge-based methods alone. Novel computing platforms will also play an important role in the future of biomolecular simulations. As quantum computing, neuromorphic computing and other architectures enter the arena, we can be sure that they will be exploited avidly by the biomolecular community. Despite the extraordinary technical impact of computers on our field and the incredible potential of artificial intelligence techniques to address many scientific problems, human intuition and intelligence will continue to be instrumental for developing ideas and pursuing new research avenues. After all, such human talent is responsible for artificial intelligence design and implementation in the first place and will probably continue to do so.

Finally, gone are the days when modelers worked in isolation. Whether on Zoom or sharing a bench, teams of multidisciplinary scientists (and likely automated machines too in the future) are collaborating to address essential problems of life, from energy to vaccines. Despite some bumps, exponential growth appears a reality in the near future, and the field of biomolecular modeling and simulation will undoubtedly continue to incorporate, innovate and digitize the inner workings of biological systems to solve the secrets of life and to develop solutions for treating human disease, improving global health and enhancing our environment.

Acknowledgements

Support from the National Institutes of Health, National Institutes of General Medical Sciences Awards R01GM055264 and R35-GM122562, NSF RAPID Award (2030377) from the Division of Mathematical Sciences, and Philip-Morris USA Inc. and Philips-Morris International to T.S. are gratefully acknowledged. Computing support from NYU HPC facility and team was instrumental for our own research throughout the decades.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Schlick T, Collepardo-Guevara R, Halvorsen LA, Jung S & Xiao X Biomolecular modeling and simulation: a field coming of age. Q. Rev. Biophys 44, 191–228 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schaefer HF Methylene: a paradigm for computational quantum chemistry. Science 231, 1100–1107 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maddox J Statistical mechanics by numbers. Nature 334, 561 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munos B Lessons from 60 years of pharmaceutical innovation. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 8, 959–968 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayden EC Human genome at then: life is complicated. Nature 464, 664–667 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindorff-Larsen K, Piana S, Dror RO & Shaw DE How fast-folding proteins fold. Science 334, 517–520 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perilla JR & Schulten K Physical properties of the HIV-1 capsid from all-atom molecular dynamics simulations. Nat. Commun 8, 15959 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acharya A et al. Supercomputer-based ensemble docking drug discovery pipeline with application to COVID-19. J. Chem. Inf. Model 60, 5832–5852 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schlick T The 2013 Nobel Prize in Chemistry celebrates computations in chemistry and biology. SIAM News 46, 1–4 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vendruscolo M & Dobson CM Protein dynamics: Moore’s Law in molecular biology. Curr. Biol 21, R68–R70 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore GE Cramming more components onto integrated circuits. Electronics 38, 114–117 (1965). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ismail S, Malone MS & Van Geest Y Exponential Organizations. Why New Organizations Are Ten Times Better, Faster, and Cheaper Than Yours (and What to Do About It) (Diversion Publishing, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wetterstrand KA DNA Sequencing Costs: Data from the NHGRI Large-Scale Genome Sequencing Program (NIH, 2016); www.genome.gov/sequencingcostsdata [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forster P, Forster L, Renfrew C & Forster M Phylogenetic network analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 9241–9243 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlick T et al. Biomolecular modeling and simulation: a prospering multidisciplinary field. Annu. Rev. Biophys 50, 267–301 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brini E, Simmerling C & Dill K Protein storytelling through physics. Science 370, eaaz3041 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cornell WD et al. A second generation force field for the simulation of proteins, nucleic acids, and organic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc 117, 5179–5197 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacKerell AD, Wiorkiewicz-Kuczera J & Karplus M An all-atom empirical energy function for the simulation of nucleic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 117, 11946–11975 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oostenbrink C, Villa A, Mark AE & Van Gunsteren WF A biomolecular force field based on the free enthalpy of hydration and solvation: the GROMOS force-field parameter sets 53A5 and 53A6. J. Comput. Chem 25, 1656–1676 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dror RO, Dirks RM, Grossman JP, Xu H & Shaw DE Biomolecular simulation: a computational microscope for molecular biology. Annu. Rev. Biophys 41, 429–452 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huggins DJ et al. Biomolecular simulations: from dynamics and mechanisms to computational assays of biological activity. Wiley. Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci 9, e1393 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel S & Brooks CL CHARMM fluctuating charge force field for proteins: I parameterization and application to bulk organic liquid simulations. J. Comput. Chem 25, 1–16 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopes PEM et al. Polarizable force field for peptides and proteins based on the classical drude oscillator. J. Chem. Theory Comput 9, 5430–5449 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang C et al. AMOEBA polarizable atomic multipole force field for nucleic acids. J. Chem. Theory Comput 14, 2084–2108 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inakollu VS, Geerke DP, Rowley CN & Yu H Polarisable force fields: what do they add in biomolecular simulations? Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 61, 182–190 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jing Z et al. Polarizable force fields for biomolecular simulations: recent advances and applications. Annu. Rev. Biophys 48, 371–394 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dauber-Osguthorpe P & Hagler AT Biomolecular force fields: where have we been, where are we now, where do we need to go and how do we get there? J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des 33, 133–203 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Spoel D Systematic design of biomolecular force fields. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 67, 18–24 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noid WG Perspective: coarse-grained models for biomolecular systems. J. Chem. Phys 139, 90901 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamerlin SCL, Vicatos S, Dryga A & Warshel A Coarse-grained (multiscale) simulations in studies of biophysical and chemical systems. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem 62, 41–64 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He Y et al. Lessons from application of the UNRES force field to predictions of structures of CASP10 targets. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 14936–14941 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maisuradze GG, Senet P, Czaplewski C, Liwo A & Scheraga HA Investigation of protein folding by coarse-grained molecular dynamics with the UNRES force field. J. Phys. Chem. A 114, 4471–4485 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piana S, Lindorff-Larsen K & Shaw DE Protein folding kinetics and thermodynamics from atomistic simulation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 17845–17850 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miao Y, Feixas F, Eun C & McCammon JA Accelerated molecular dynamics simulations of protein folding. J. Comput. Chem 36, 1536–1549 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piana S & Shaw DE Atomic-level description of protein folding inside the GroEL cavity. J. Phys. Chem. B 122, 11440–11449 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Durrant JD et al. Mesoscale all-atom influenza virus simulations suggest new substrate binding mechanism. ACS Cent. Sci 6, 189–196 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu A et al. A multiscale coarse-grained model of the SARS-CoV-2 virion. Biophys. J 10.1016/j.bpj.2020.10.048 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Radhakrishnan R et al. Regulation of DNA repair fidelity by molecular checkpoints: ‘gates’ in DNA polymerase β’s substrate selection. Biochemistry 45, 15142–15156 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jung J et al. Scaling molecular dynamics beyond 100,000 processor cores for large-scale biophysical simulations. J. Comput. Chem 40, 1919–1930 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bascom G & Schlick T in Translational Epigenetics Vol. 2 (eds Lavelle C & Victor J-M) 123–147 (Academic Press, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wedemann G & Langowski J Computer simulation of the 30-nanometer chromatin fiber. Biophys. J 82, 2847–2859 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith MD & Smith JC Repurposing therapeutics for COVID-19: supercomputer-based docking to the SARS-CoV-2 viral spike protein and viral spike protein–human ACE2 interface. Preprint at 10.26434/chemrxiv.11871402.v4 (2020). [DOI]

- 43.Van Gunsteren WF et al. Biomolecular modeling: goals, problems, perspectives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 45, 4064–4092 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Casalino L et al. Beyond shielding: the roles of glycans in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. ACS Cent. Sci 6, 1722–1734 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu N, Guo Y, Ning S & Duan M Phosphorylation regulates the binding of intrinsically disordered proteins via a flexible conformation selection mechanism. Commun. Chem 3, 123 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qi R et al. Elucidating the phosphate binding mode of phosphate-binding protein: the critical effect of buffer solution. J. Phys. Chem. B 122, 6371–6376 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Warme PK, Momany FA, Rumball SV, Tuttle RW & Scheraga HA Computation of structures of homologous proteins. Alpha-lactalbumin from lysozyme. Biochemistry 13, 768–782 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones D & Thornton J Protein fold recognition. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des 7, 439–456 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rohl CA, Strauss CEM, Misura KMS & Baker D Protein structure prediction using Rosetta. Methods Enzymol. 383, 66–93 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abriata LA, Tamò GE, Monastyrskyy B, Kryshtafovych A & Dal Peraro M Assessment of hard target modeling in CASP12 reveals an emerging role of alignment-based contact prediction methods. Proteins 86, 97–112 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marks DS et al. Protein 3D structure computed from evolutionary sequence variation. PLoS ONE 6, e28766 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ovchinnikov S et al. Improved de novo structure prediction in CASP11 by incorporating coevolution information into Rosetta. Proteins 84, 67–75 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kryshtafovych A, Schwede T, Topf M, Fidelis K & Moult J Critical assessment of methods of protein structure prediction (CASP)—round XIII. Proteins 87, 1011–1020 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Callaway E ‘It will change everything’: DeepMind’s AI makes gigantic leap in solving protein structures. Nature 588, 203–204 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang L et al. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved α-ketoamide inhibitors. Science 368, 409–412 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mohammad T et al. Identification of high-affinity inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease: towards the development of effective COVID-19 therapy. Virus Res. 288, 198102 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou Y et al. Artificial intelligence in COVID-19 drug repurposing. Lancet Digit. Health 2, e667–e676 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Laing C et al. Predicting helical topologies in RNA junctions as tree graphs. PLoS ONE 8, e71947 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Durrant JD & McCammon JA NNScore: a neural-network-based scoring function for the characterization of protein–ligand complexes. J. Chem. Inf. Model 50, 1865–1871 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang C & Zhang Y Improving scoring-docking-screening powers of protein–ligand scoring functions using random forest. J. Comput. Chem 38, 169–177 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Botu V, Batra R, Chapman J & Ramprasad R Machine learning force fields: construction, validation, and outlook. J. Phys. Chem. C 121, 511–522 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pitera JW & Chodera JD On the use of experimental observations to bias simulated ensembles. J. Chem. Theory Comput 8, 3445–3451 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hummer G & Köfinger J Bayesian ensemble refinement by replica simulations and reweighting. J. Chem. Phys 143, 243150 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Park H, Lee GR, Heo L & Seok C Protein loop modeling using a new hybrid energy function and its application to modeling in inaccurate structural environments. PLoS ONE 9, e113811 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kortemme T, Morozov AV & Baker D An orientation-dependent hydrogen bonding potential improves prediction of specificity and structure for proteins and protein–protein complexes. J. Mol. Biol 326, 1239–1259 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Raval A, Piana S, Eastwood MP, Dror RO & Shaw DE Refinement of protein structure homology models via long, all-atom molecular dynamics simulations. Proteins 80, 2071–2079 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang J, Liang Y & Zhang Y Atomic-level protein structure refinement using fragment-guided molecular dynamics conformation sampling. Structure 19, 1784–1795 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Heo L & Feig M High-accuracy protein structures by combining machine-learning with physics-based refinement. Proteins 88, 637–642 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Borhani TN, García-Muñoz S, Vanesa Luciani C, Galindo A & Adjiman CS Hybrid QSPR models for the prediction of the free energy of solvation of organic solute/solvent pairs. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 21, 13706–13720 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ash J & Fourches D Characterizing the chemical space of ERK2 kinase inhibitors using descriptors computed from molecular dynamics trajectories. J. Chem. Inf. Model 57, 1286–1299 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Koepnick B et al. De novo protein design by citizen scientists. Nature 570, 390–394 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Darden T, York D & Pedersen L Particle mesh Ewald: an N·log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys 98, 10089–10092 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hockney RW & Eastwood JW Computer Simulation Using Particles (Taylor & Francis, 1988). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Verlet L Computer ‘experiments’ on classical fluids. I. Thermodynamical properties of Lennard–Jones molecules. Phys. Rev 159, 98–103 (1967). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Barth E & Schlick T Overcoming stability limitations in biomolecular dynamics. I. Combining force splitting via extrapolation with Langevin dynamics in LN. J. Chem. Phys 109, 1617–1632 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Radhakrishnan R & Schlick T Orchestration of cooperative events in DNA synthesis and repair mechanism unraveled by transition path sampling of DNA polymerase β’s closing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 5970–5975 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chen PY & Tuckerman ME Molecular dynamics based enhanced sampling of collective variables with very large time steps. J. Chem. Phys 148, 24106 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Batcho PF, Case DA & Schlick T Optimized particle-mesh Ewald/multiple-time step integration for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Phys 115, 4003–4018 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hohenberg P & Kohn W Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev 136, B864–B871 (1964). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kohn W & Sham LJ Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev 140, A1133–A1138 (1965). [Google Scholar]

- 81.Su NQ & Xu X Development of new density functional approximations. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem 68, 155–182 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ban F, Rankin KN, Gauld JW & Boyd RJ Recent applications of density functional theory calculations to biomolecules. Theor. Chem. Acc 108, 1–11 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 83.Car R & Parrinello M Unified approach for molecular dynamics and density-functional theory. Phys. Rev. Lett 55, 2471–2474 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Marx D & Hutter J Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics: Basic Theory and Advanced Methods (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2009); 10.1017/CBO9780511609633 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Iftimie R, Minary P & Tuckerman ME Ab initio molecular dynamics: concepts, recent developments, and future trends. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 6654–6659 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Senn HM & Thiel W QM/MM methods for biomolecular systems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 48, 1198–1229 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Warshel A & Levitt M Theoretical studies of enzymic reactions: dielectric, electrostatic and steric stabilization of the carbonium ion in the reaction of lysozyme. J. Mol. Biol 103, 227–249 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Carloni P, Rothlisberger U & Parrinello M The role and perspective of ab initio molecular dynamics in the study of biological systems. Acc. Chem. Res 35, 455–464 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wallrapp FH & Guallar V Mixed quantum mechanics and molecular mechanics methods: looking inside proteins. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci 1, 315–322 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zheng M & Waller MP Adaptive quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics methods. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci 6, 369–385 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang YJ, Khorshidi A, Kastlunger G & Peterson AA The potential for machine learning in hybrid QM/MM calculations. J. Chem. Phys 148, 241740 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shen L, Wu J & Yang W Multiscale quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics simulations with neural networks. J. Chem. Theory Comput 12, 4934–4946 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yang YI, Shao Q, Zhang J, Yang L & Gao YQ Enhanced sampling in molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys 151, 70902 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Liao Q in Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science Vol. 170 (eds. Strodel B & Barz B) 177–213 (Academic Press, 2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pan AC, Weinreich TM, Piana S & Shaw DE Demonstrating an order-of-magnitude sampling enhancement in molecular dynamics simulations of complex protein systems. J. Chem. Theory Comput 12, 1360–1367 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Torrie GM & Valleau JP Nonphysical sampling distributions in Monte Carlo free-energy estimation: umbrella sampling. J. Comput. Phys 23, 187–199 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 97.Laio A & Parrinello M Escaping free-energy minima. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 12562–12566 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lu H & Schulten K Steered molecular dynamics simulations of force-induced protein domain unfolding. Proteins 35, 453–463 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sugita Y & Okamoto Y Replica-exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding. Chem. Phys. Lett 314, 141–151 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hamelberg D, Mongan J & McCammon JA Accelerated molecular dynamics: a promising and efficient simulation method for biomolecules. J. Chem. Phys 120, 11919–11929 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Piana S, Lindorff-Larsen K & Shaw DE Atomistic description of the folding of a dimeric protein. J. Phys. Chem. B 117, 12935–12942 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Husic BE & Pande VS Markov state models: from an art to a science. J. Am. Chem. Soc 140, 2386–2396 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schwantes CR, McGibbon RT & Pande VS Perspective: Markov models for long-timescale biomolecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys 141, 90901 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Straatsma TP & Berendsen HJC Free energy of ionic hydration: analysis of a thermodynamic integration technique to evaluate free energy differences by molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Phys 89, 5876–5886 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chipot C & Pohorille A Free Energy Calculations (Springer-Verlag, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 106.Deng Y & Roux B Computations of standard binding free energies with molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 2234–2246 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chipot C in New Algorithms for Macromolecular Simulation (eds. Leimkuhler B et al.) 185–211 (Springer, 2006); 10.1007/3-540-31618-3_12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Schöberl M, Zabaras N & Koutsourelakis PS Predictive collective variable discovery with deep Bayesian models. J. Chem. Phys 150, 24109 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bonati L, Zhang YY & Parrinello M Neural networks-based variationally enhanced sampling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 17641–17647 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhang J, Yang YI & Noé F Targeted adversarial learning optimized sampling. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 10, 5791–5797 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Behler J & Parrinello M Generalized neural-network representation of high-dimensional potential-energy surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett 98, 146401 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Noé F, Tkatchenko A, Müller KR & Clementi C Machine learning for molecular simulation. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem 71, 361–390 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Warshel A & Karplus M Calculation of ground and excited state potential surfaces of conjugated Molecules. I. Formulation and parametrization. J. Am. Chem. Soc 94, 5612–5625 (1972). [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kmiecik S et al. Coarse-grained protein models and their applications. Chem. Rev 116, 7898–7936 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Dans PD, Walther J, Gómez H & Orozco M Multiscale simulation of DNA. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 37, 29–45 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Potoyan DA, Savelyev A & Papoian GA Recent successes in coarse-grained modeling of DNA. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci 3, 69–83 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 117.Šponer J et al. RNA structural dynamics as captured by molecular simulations: a comprehensive overview. Chem. Rev 118, 4177–4338 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Dawson WK, Maciejczyk M, Jankowska EJ & Bujnicki JM Coarse-grained modeling of RNA 3D structure. Methods 103, 138–156 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Schlick T, Zhu Q, Jain S & Yan S Structure-altering mutations of the SARS-CoV-2 frameshifting RNA element. Biophys. J 120, 1040–1053 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Marrink SJ & Tieleman DP Perspective on the Martini model. Chem. Soc. Rev 42, 6801–6822 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Cascella M & Vanni S in Chemical Modelling Vol. 12 (eds. Springborg M & Joswig J-O) 1–52 (Royal Society of Chemistry, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 122.Soares TA, Vanni S, Milano G & Cascella M Toward chemically resolved computer simulations of dynamics and remodeling of biological membranes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 8, 3586–3594 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Portillo-Ledesma S & Schlick T Bridging chromatin structure and function over a range of experimental spatial and temporal scales by molecular modeling. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci 10, wcms.1434 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Bendandi A, Dante S, Zia SR, Diaspro A & Rocchia W Chromatin compaction multiscale modeling: a complex synergy between theory, simulation, and experiment. Front. Mol. Biosci 7, 15 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Stehr R et al. Exploring the conformational space of chromatin fibers and their stability by numerical dynamic phase diagrams. Biophys. J 98, 1028–1037 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Fan Y, Korolev N, Lyubartsev AP & Nordenskiöld L An advanced coarse-grained nucleosome core particle model for computer simulations of nucleosome–nucleosome interactions under varying ionic conditions. PLoS ONE 8, e54228 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kulaeva OI et al. Internucleosomal interactions mediated by histone tails allow distant communication in chromatin. J. Biol. Chem 287, 20248–20257 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.MacPherson Q, Beltran B & Spakowitz AJ Bottom-up modeling of chromatin segregation due to epigenetic modifications. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 12739–12744 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Lequieu J, Córdoba A, Moller J & de Pablo JJ 1CPN: a coarse-grained multi-scale model of chromatin. J. Chem. Phys 150, 215102 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Bascom G, Myers C & Schlick T Mesoscale modeling reveals formation of an epigenetically driven hoxc gene hubs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 4955–4962 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Stone JE, Hardy DJ, Ufimtsev IS & Schulten K GPU-accelerated molecular modeling coming of age. J. Mol. Graph. Model 29, 116–125 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Harger M et al. Tinker-OpenMM: absolute and relative alchemical free energies using AMOEBA on GPUs. J. Comput. Chem 38, 2047–2055 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Jász Á, Rák Á, Ladjánszki I, Tornai GJ & Cserey G Towards chemically accurate QM/MM simulations on GPUs. J. Mol. Graph. Model 96, 107536 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Nitsche MA, Ferreria M, Mocskos EE & Lebrero MCG GPU accelerated implementation of density functional theory for hybrid QM/MM simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput 10, 959–967 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Active CPUs and GPUs by OS. Folding@home https://stats.foldingathome.org/os (accessed 1 March 2021).

- 136.Zimmerman MI et al. Citizen scientists create an exascale computer to combat COVID-19. Preprint atbioRxiv 10.1101/2020.06.27.175430 (2020). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Acun B et al. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD on the summit system. IBM J. Res. Dev 62, 1–9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Kohlhoff KJ et al. Cloud-based simulations on Google Exacycle reveal ligand modulation of GPCR activation pathways. Nat. Chem 6, 15–21 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Gorgulla C et al. A multi-pronged approach targeting SARS-CoV-2 proteins using ultra-large virtual screening. iScience 24, 102021 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Stone JE, Messmer P, Sisneros R & Schulten K High performance molecular visualization: in-situ and parallel rendering with EGL. In Proc. 2016 IEEE 30th International Parallel Distributed Processing Symposium 1014–1023 (IEEE, 2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Ribeiro JV et al. QwikMD—integrative molecular dynamics toolkit for novices and experts. Sci. Rep 6, 26536 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Singharoy A et al. Molecular dynamics-based refinement and validation for sub-5 Å cryo-electron microscopy maps. Elife 5, e16105 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Shaw DE et al. Anton, a special-purpose machine for molecular dynamics simulation. Commun. ACM 51, 91–97 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 144.Young MA & Beveridge DL Molecular dynamics simulations of an oligonucleotide duplex with adenine tracts phased by a full helix turn. J. Mol. Biol 281, 675–687 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Duan Y & Kollman PA Pathways to a protein folding intermediate observed in a 1-microsecond simulation in aqueous solution. Science 282, 740–744 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Izrailev S, Crofts AR, Berry EA & Schulten K Steered molecular dynamics simulation of the Rieske subunit motion in the cytochrome bc1 complex. Biophys. J 77, 1753–1768 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Pérez A, Luque FJ & Orozco M Dynamics of B-DNA on the microsecond time scale. J. Am. Chem. Soc 129, 14739–14745 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Freddolino PL, Liu F, Gruebele M & Schulten K Ten-microsecond molecular dynamics simulation of a fast-folding WW domain. Biophys. J 94, L75–L77 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Zanetti-Polzi L et al. Parallel folding pathways of Fip35 WW domain explained by infrared spectra and their computer simulation. FEBS Lett 591, 3265–3275 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Shaw DE et al. Atomic-level characterization of the structural dynamics of proteins. Science 330, 341–346 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Gamini R, Han W, Stone JE & Schulten K Assembly of Nsp1 nucleoporins provides insight into nuclear pore complex gating. PLoS Comput. Biol 10, e1003488 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Reddy T et al. Nothing to sneeze at: a dynamic and integrative computational model of an influenza a virion. Structure 23, 584–597 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Song X et al. Mechanism of NMDA receptor channel block by MK-801 and memantine. Nature 556, 515–519 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Liu C et al. Cyclophilin A stabilizes the HIV-1 capsid through a novel non-canonical binding site. Nat. Commun 7, 10714 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Senior AW et al. Improved protein structure prediction using potentials from deep learning. Nature 577, 706–710 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Miao Y et al. Accelerated structure-based design of chemically diverse allosteric modulators of a muscarinic G protein-coupled receptor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, E5675–E5684 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Rollins NJ et al. Inferring protein 3D structure from deep mutation scans. Nat. Genet 51, 1170–1176 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.McCammon JA, Gelin BR & Karplus M Dynamics of folded proteins. Nature 267, 585–590 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.de Vlieg J, Berendsen HJC & van Gunsteren WF An NMR-based molecular dynamics simulation of the interaction of the lac repressor headpiece and its operator in aqueous solution. Proteins 6, 104–127 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Field MJ, Bash PA & Karplus M A combined quantum mechanical and molecular mechanical potential for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem 11, 700–733 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 161.Lane TJ, Shukla D, Beauchamp KA & Pande VS To milliseconds and beyond: challenges in the simulation of protein folding. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 23, 58–65 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Ode H, Nakashima M, Kitamura S, Sugiura W & Sato H Molecular dynamics simulation in virus research. Front. Microbiol 3, 258 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Mulholland AJ & Richards WG Acetyl-CoA enolization in citrate synthase: a quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical (QM/MM) study. Proteins 27, 9–25 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Zhao G et al. Mature HIV-1 capsid structure by cryo-electron microscopy and all-atom molecular dynamics. Nature 497, 643–646 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]