Abstract

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common disorder that affects various facets of fertility. Although the ovarian and metabolic aspects of the disease is well studied, its role in uterine dysfunction is not well understood. Our objective was to review the features of endometrial and uterine aberrations in women with PCOS. A systematic literature search was performed in PubMed, Medline, and the Cochrane Library databases for papers published in English up to March 2020. The following key words were used for the search: polycystic ovary syndrome, poly cystic ovarian disease, polycystic ovaries, PCOS, PCOD, PCO, PCOM, oligoovulation, anovulation, oligomenorrhea, amenorrhea, hyperandrogenism and this was combined with terms; endometrium, infertility, uterus, progesterone resistance, endometrial hyperplasia, pregnancy outcomes, preterm delivery. In this review, we highlight various uterine pathologies that are associated with PCOS and explore its impact on fertility. We also discuss key uterine molecular pathways that are altered in PCOS that may be related to infertility, endometrial hyperplasia and cancer.

Keywords: PCOS, Ovary, Uterus, Infertility

Introduction

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is a multifactorial disorder affecting 8%−13% of all reproductive age women depending on the population studied and definitions used (1–3). This condition was first described by Stein and Leventhal in 1935 (4), who speculated that anovulation in these women is a result of a thickened ovarian capsule. The etiology of the disease has perplexed reproductive endocrinologists for many years and still continues to do so. While the diagnostic criteria for PCOS remain controversial, the 2003 Rotterdam consensus is the most widely accepted definition. Based on the consensus, PCOS is diagnosed if two of the three following criteria are present: oligoovulation and/or anovulation, biochemical or clinical evidence of excessive androgen action, and polycystic ovaries (5). Despite extensive progress in treatments approaches, guidelines limitations resulted in inconsistent guidance for clinicians and women. In 2018, Teede et al. proposed an international guideline for the assessment and management of PCOS. This comprehensive evidence-based guideline builds on prior high quality guidelines and provides a single source of evidence-based recommendations to guide clinical practice with the opportunity for adaptation in relevant health systems (2).

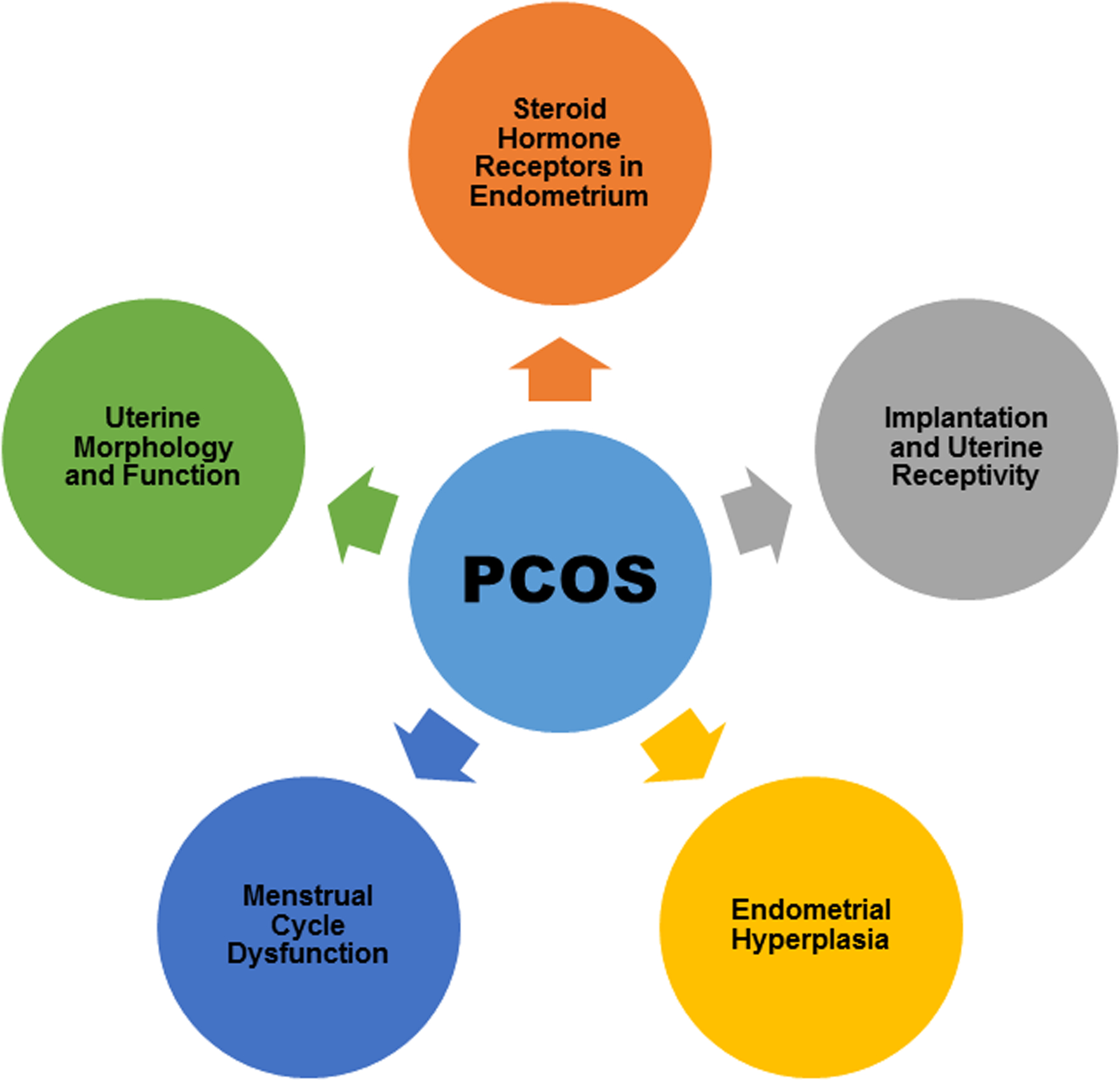

PCOS is often recognized as a reproductive endocrinopathy, as the majority of women with PCOS have anovulatory cycles, irregular/heavy bleeding, acne, hirsutism, and infertility. However, the spectrum of the syndrome is much wider. PCOS is associated with metabolic alterations related to insulin resistance, including impaired glucose tolerance, hyperinsulinemia, early onset type 2 diabetes, obesity, metabolic syndrome, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and increased risk of cardiovascular disease (6–9). PCOS therefore can be characterized as a complex syndrome with reproductive, endocrine, and metabolic manifestations. Anovulation is historically believed to be the main reason for infertility in PCOS patients. Evidence suggest that even after treatment with assisted reproductive techniques, pregnancy outcome in patients with PCOS is less than satisfactory (10–12). It has been reported that women with PCOS had a significantly greater risk of spontaneous abortion compared with non-PCOS women (25 versus 18%, P < 0.01) (13). Obesity is closely associated with PCOS, which is a known risk factor for early pregnancy loss (14), therefore it is still controversial whether PCOS is attributed to miscarriage independently. One study by Lou et al. indicated women with PCOS were at increased risk of early miscarriage following euploid embryo transfer independent of age and BMI (15). These authors hypothesized that the endocrinological disorder impacting endometrial function in PCOS could be a more important factor contributing to compromised pregnancy outcome. There are other studies that show that both poor oocyte quality and impaired endometrial receptivity can result in implantation failure in the PCOS population (16, 17). Women with PCOS are also at higher risk of developing endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer, which can further alter endometrial receptivity and/or chance for future pregnancy (16, 18, 19). Therefore, the impact of this syndrome, goes beyond the ovary in many facets. This review, will address the current literature on the impact of PCOS and associated metabolic and endocrine derangements on the uterus. (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

The impact of the PCOS on the uterus

Methods

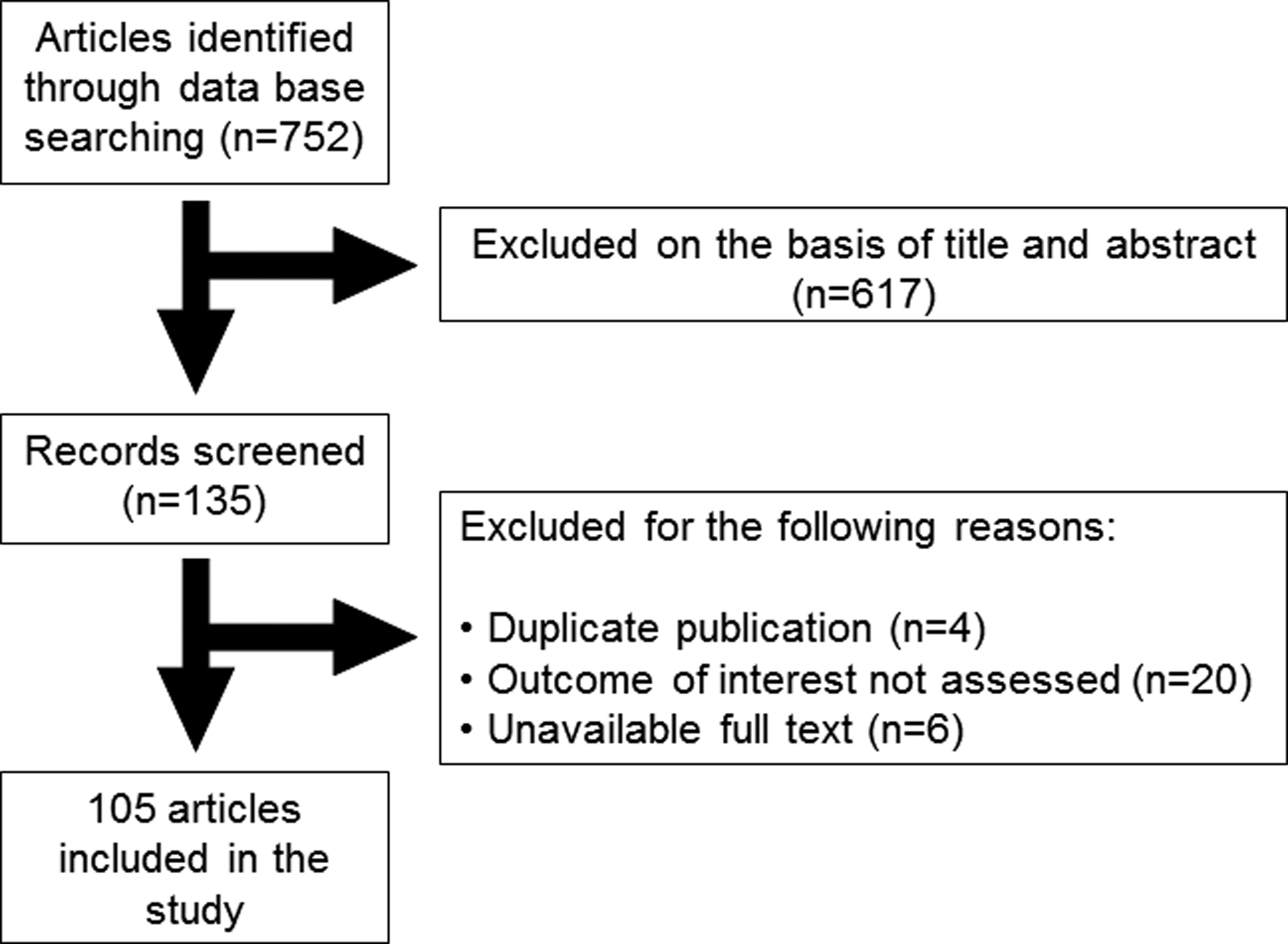

An extensive literature search was performed in PubMed, Medline, and the Cochrane Library. Literature available up to March 2020 was included. The search was limited to articles published in English. A search algorithm was developed incorporating the terms polycystic ovary syndrome, poly cystic ovarian disease, polycystic ovaries, PCOS, PCOD, PCO, PCOM, oligoovulation, anovulation, oligomenorrhea, amenorrhea, hyperandrogenism and this was combined with terms; endometrium, infertility, uterus, progesterone resistance, endometrial hyperplasia, pregnancy outcomes, preterm delivery. Additional journal articles were identified from the bibliographies of the studies included. Exclusion criteria include duplicate publications, publications where outcomes of interests were not assessed, and publications without full text. We also excluded those manuscripts for which more recent published data was available. We limited the number of experimental studies when clinical data was available. Duplicate studies were removed using the EndNote software, version X7.0 (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, USA).

All articles were initially screened for title and abstract. Full texts of eligible articles were subsequently selected. Systematic reviews with meta-analysis were initially included for each specific subject. Recently published articles, which were not included in the systematic reviews, were also included. When specific data for PCOS patients were lacking, data reported in the presence of metabolic disorder involved in PCOS (like hyperandrogenism, hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance) were included. A total number of 105 studies were included in this review as illustrated in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Literature search and review flow chart for selection of literature

Menstrual cycle and uterine dysfunction in women with PCOS

The uterine endometrium is a hormone-dependent tissue that consists of stromal (fibroblastic and muscular) and epithelial (luminal and glandular) compartments, each with a distinct identity and role in reproductive physiology (20). Each of these compartments responds to circulating levels of ovarian derived steroid hormones (progestogens, estrogens and androgens) and hence divide the endometrium’s monthly life cycle into proliferative and secretory phases (21, 22). The proliferative phase is determined by an extensive estrogen-driven proliferation and mitotic activity, with the rising estrogen concentrations promoting the expression of estrogen receptors (ER), which are highest during the late proliferative phase (23, 24). ERα is the main ER in cycling endometrium. Estradiol also increases progesterone receptor (PR) expression, thus enabling progesterone action on the endometrium after ovulation that in turn initiates the secretory phase of the endometrial cycle (25). The secretory phase is divided into 3 distinct stages of early, mid and late secretory stage. Following ovulation, progesterone secreted by corpus luteum inhibits endometrial ER expression and thus estrogen action, especially in the epithelial glands (24). This results in inhibition of cellular proliferation, DNA synthesis and cellular mitotic activity, which initiates endometrial reprogramming and differentiation, pseudodecidualization, in the stromal compartment. All of these actions lead to the preparation of the endometrium for potential embryo implantation, the window of implantation (WOI) (24). In the absence of implantation, withdrawal of progesterone and estrogen, especially progesterone, causes menstruation (25). Progesterone also down regulates androgen receptors (ARs) in glandular and luminal epithelium and stroma (26). Pathway analysis suggests that androgen-dependent changes in gene expression may have a significant impact on stromal cell proliferation, migration, and survival (25, 26).

In women with PCOS, the regulatory roles of progesterone and progesterone withdrawal in the endometrium is deficient secondary to oligo-ovulatory or anovulatory cycles (16). This results in a relatively constant low circulating level of estrogens and endometrial changes comparable to the follicular phase throughout the cycle (3). On the other hand, peripheral conversion of androstenedione to estrone in adipose tissue, and increased free estradiol and testosterone levels in the setting of hyperinsulinemia amplifies the stimulatory and mitogenic effects from unopposed estradiol exposure. This can lead to unpredictable bleeding patterns, and heavy menstrual bleeding (27).

Menstrual dysfunction and uterine abnormalities in adolescents with PCOS

Diagnosing PCOS in adolescents can be challenging due to the overlap of the symptoms with normal adolescent physiology. For instance, it can be difficult to distinguish between perimenarchal versus PCOS-caused anovulation. In normal, healthy girls, half of menstrual cycles are anovulatory in the first two post-menarchal years (28). In addition, half of the patients with physiologic adolescent anovulation have similar biochemical changes (i.e. hyperandrogenism) as PCOS. When these symptoms extend beyond 2 years, PCOS becomes more likely diagnosis (28).

Several studies in the current literature have suggested juvenile menstrual disorders to be a marker of hyperandrogenemia and increased risk of PCOS and metabolic disorder later in life (29–32). PCOS is reported to be diagnosed more often in adolescents with abnormal uterine bleeding who required hospital admission (33). Ubranska et al. has reported a correlation between the severity of bleeding and incidence of PCOS syndrome (32). Shah et al has described ultrasound characteristics of endometrial thickness and uterine measurements in a group of adolescent girls diagnosed with PCOS (33). In this study while endometrial thickness was increased in a subset of PCOS adolescents likely due to unopposed estrogen exposure, uterine length was reported to be shorter. The authors hypothesized that shorter uterine length may be due to the chronic imbalance between estrogen and androgens. It is important to keep the diagnosis of PCOS on the differential when diagnosing and treating adolescence to help identify risk factors for disease and future potential co-morbidities.

Steroid hormone receptors in the endometrium of women with PCOS

The physiology of the endometrium is highly dependent on the circulating steroid hormones and local expression of their specific receptors. Several studies evaluating endometrial samples of women with PCOS who had anovulation of unknown duration have shown an increase in the expression of ERα and AR in the stromal and epithelial compartments in comparison to normal cycling endometrium (34–36). It is well established that estrogen upregulate the endometrial expression of its own receptors (ERα and ERβ) and that of AR (37). The high expression of ERs and AR observed in these studies may be explained, in part, by the progestin-unopposed hyperestrogenic condition that is a characteristic of PCOS. Perhaps estrogens are more “potent” in PCOS through the action of coactivators. A report by Gregory et al. indicated an overexpression of a steroid receptor coactivator family p160 in both proliferative and secretory endometrium (38). Enhanced p160 expression renders PCOS endometrium more sensitive to the actions of estrogens, which in parallel with increased ER expression accounts for the higher incidence of endometrial abnormality in women with PCOS (38).

A study by Quezada et al. investigated endometrial samples obtained during the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle from both fertile cycling woman and patients with PCOS. Interestingly, a greater percentage of epithelial cells exhibit positive staining with ERα isoform in PCOS endometrium compared to normal endometrium. As mentioned previously, marked inhibition of ERα in mid-secretory phase heralds the opening of WOI. Increased expression of ERα in ovulatory PCOS patients may contribute to higher implantation failure and lower pregnancy rates in women with PCOS. No differences were observed in the percentage of positively stained endometrial cells for ERβ or AR (39).

In the same study PR expression was overall higher in ovulatory PCOS endometrium, particularly in the epithelial compartment (39). PR is essential in the mid secretory phase for the WOI to induce a pseudodecidualization reaction in the stromal compartment. It’s been shown that there’s a shift in PR expression from the epithelial compartment out to the stroma during the secretory phase (40). Hence, the abundance of ER and PR in the epithelium, and not in the stroma, of mid-secretory phase endometrium may indicate altered progesterone action in women with PCOS (41, 42). Decreased responsiveness to bioavailable progesterone in the endometrium of PCOS women implies progesterone resistance. Alterations in the expression or function of PR coactivators, chaperones, and co-chaperones that are bound to PR before activation have been implicated in progesterone resistance (43). While the exact mechanism of progesterone resistance is not clear, several human studies indicate that nuclear PR-signaling pathways are associated with progesterone resistance in PCOS women (44–46). The hypothesis of progesterone resistance was further examined by Savaris et al. who compared gene expression profiles of mid-secretory endometrium of normal fertile women vs. PCOS patients, either induced to ovulate with clomiphene citrate or from a modeled secretory phase using exogenous administration of progesterone (46). They concluded that independent of clomiphene citrate, the difference in gene expression provide essential evidence of progesterone resistance in mid-secretory PCOS endometrium (46).

Implantation and uterine receptivity in PCOS patients

Changes in the expression of endometrial steroid receptor and coactivators in PCOS patients are associated with reduced endometrial receptivity and enhanced actions of estrogen. The term “endometrial receptivity” was introduced to define the state of the endometrium during the window of implantation. Implantation occurs approximately 6 days after ovulation, when the endometrium is exhibiting a receptive phenotype, which, as described earlier, is known as WOI (39). Progesterone is essential for successful embryo implantation and post-implantation embryo survival in all placental mammals, including humans. Progesterone action after ovulation promotes decidualization of the endometrial stromal cells. Decidualized fibroblasts from endometrial stroma undergo morphological and functional alterations that result in the accumulation of glycogen and lipids in the cytoplasm, providing a source of nutrition for the developing embryo prior to placental development (47, 48). The effect of progesterone on decidualization also depends on activation of other signaling pathways and transcription factors. Amongst the interacting transcription factors are a member of forkhead box class O protein family (FOXO1) and homeobox class A family (HOXA10) (49, 50). These transcription factors play a vital role in differentiation of the endometrium and endometrial receptivity. HOX genes are responsible for mediating sex hormone’s function and are essential for the proliferation, differentiation of the stromal cells during each reproductive cycle. Alterations of endometrial HOXA10 expression in animal models has demonstrated the necessary role of this gene in development of the endometrium and receptivity to embryonic implantation (51). Interestingly, a study by Cermik et al reported decreased HOXA10 expression in the endometrium of oligo-ovulatory PCOS patients compared with controls (52). The same study identified elevated testosterone as a negative regulator of HOXA10 expression in the endometrium of PCOS patients, as down regulation of HOXA10 expression was noted in cultured endometrial cells treated by testosterone in vitro (52). This effect was reversible by a testosterone blockade with flutamide. Therefore, perhaps the receptivity in these patients is also altered (52).

The extracellular matrix (ECM) not only provides tissue support, its functional macromolecules are also involved in the regulation of cell properties and function. The ECM and its interaction between and endometrial cells play an important role in endometrial remodeling and decidualization. The interaction between endometrial cells and the ECM is mediated by several classes of cell adhesion molecules, one of the most important being integrins (53, 54). In normal endometrium expression of both units of αν and β3 integrins in the endometrium appears to be cycle specific. Immunostaining for αν was found to be increased throughout the menstrual cycle, while the β3 subunit only appeared abruptly after day 19. Therefore, presence of αν β3-integrin is one of the biomarkers of endometrial receptivity (55). Studies have suggested delayed and decreased expression of integrins in the endometrium of women with PCOS (34, 39). However universal data regarding significant differences in abundance of integrins in endometrium of women with PCOS is conflicting with no consensus on integrin levels in the endometrium of women with PCOS (39, 56, 57). A recent study in PCOS women undergoing in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection pointed out beneficial effects of metformin on endometrial receptivity through dose-dependent upregulation of HOXA10 and β3-integrin (58) again pointing to alteration in receptivity in PCOS women.

Insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) is a pleiotropic hormone, exhibiting different effects and activating different intracellular signaling pathways, depending on its target tissue. Insulin-like growth factors and related peptides are believed to regulate and mediate the actions of estrogen and progesterone on the endometrium. Estrogen stimulates IGF-1 gene expression in the endometrium, and IGF-1 in turn mediates estrogen action. IGF binding protein (IGFBP)-1 is abundantly secreted by decidualized endometrial stromal cells under the action of progesterone, and is a recognized biomarker of decidualized and pregnant endometrium (59). Hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance is a common metabolic feature in lean and obese PCOS patients. Hyperinsulinemic state inhibits endometrial decidualization and expression of IGFBP-1 in stromal fibroblasts impairing PCOS endometrial receptivity (60).

The uterus undergoes dramatic physiological and morphological changes during peri-implantation period, which are orchestrated by ovarian hormones, as well as morphogens, growth factors, and transcription factors (61, 62) The existence and role of ligand–receptor signaling mechanisms operating in the peri-implantation uterus have been extensively studied (47). Glycosaminoglycans are natural heteropolysaccharides that are present in every mammalian tissue. Glycoproteins and sulfated glycosaminoglycans such as heparin, and heparan sulfate are integral parts of ECM and have an important role in cell recognition, migration, differentiation and proliferation. Transportation and receptor interaction with the ligands, which is facilitated through binding to heparan sulfate, are crucial for the subsequent signaling cascade activation in target cells. It has been shown in a rodent model that the level of sulfation of heparan sulfate chains in infertile female mice is decreased (63). On the contrary, a study by Giordano et al, has shown an increased level of heparan sulfate in the endometrium of PCOS patients (64). The study concluded that increased level of heparan sulfate in woman with PCOS may lead to interference with maternal-fetal recognition. Further studies are essential to demonstrate the causation and to investigate for potential avenues that may lead to decreased fertility as seen in the PCOS population.

Researchers have explored several signaling proteins such as interleukins, receptors and ligands, cytokines and growth factors to determine how the embryo implants in the endometrium. A study by Piltonen et al suggested an altered inflammatory cytokine and metalloproteinase (MMP) profile in a subset of PCOS endometrium that had decidualization failure. These researchers reported an increase in basal levels of IL-6 and MMP in cultured PCOS endometrium with blunted decidualization (65). Post steroid (estradiol and progesterone) treatment response in the same subset of the cultured endometrial samples was associated with increased IL-8 and MMP compared to the controls (65). These authors indicated that aberrant decidualization response with concomitant pro-inflammatory release of cytokines and MMP might lead to sub-optimal endometrial environment for implantation (65).

Germeyer et al. showed for the first time that metformin influences the decidualization process of stromal cells in vitro, leading to a lower expression of prolactin as well as IGFBP-1. Furthermore, IL-8 and IL-1b gene expression was altered by metformin. IL-8 as well as IL-1b showed an increased expression, particularly short-term, but also significantly long-term, after metformin stimulation (66). Recently Xiong et al. has further investigated the molecular mechanism of metformin in estradiol/ progesterone induced decidualization of endometrial cells in PCOS patients. They showed that metformin use can induce the upregulation of IL-6, IL-8 and IL-1β levels in decidualized endometrial cells. They further revealed that metformin alleviated decidualization of endometrial cells by modulating secretion of multiple cytokines, inhibiting expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9, activating p38-MAPK signaling (67). Altogether it seems that PCOS patients have altered endometrial receptivity through a number of possible mechanisms including alterations in cytokines, MMP, and GAGs as well as expression of HOXA10, integrins, and IGFBP-1 (68).

Overall, the exact mechanism of implantation failure is still poorly understood in patients with PCOS. This is largely due to a lack of data as studies in humans have mostly been in cycles outside of pregnancy and genetic suppression experiments, whether in animal models or in vitro, provide only indirect evidence. The reduced expression of uterine receptivity markers and lack of regulation of expression and activity of steroid receptors can contribute to the low pregnancy rate observed in women with PCOS; however, whether these alterations are due to inadequate progesterone action or increased insulin and androgen action remains to be determined.

Endometrial hyperplasia

The association between PCOS and endometrial carcinoma (EC) was initially described more than 60 years ago (69, 70). A systematic review showed that the risk of EC was three times higher in women with PCOS compared to women without the disease (71), and also noted in a meta-analysis demonstrating that women with PCOS had a 3 fold increased odds of developing EC (OR 2.90, 95% CI 1.52–5.48) (72). Further, EC is usually preceded by endometrial hyperplasia (73), and a case–control study showed that women with PCOS and endometrial hyperplasia have a four times greater risk of developing EC than non-PCOS women (74).

Increased risk of endometrial cancer in PCOS is usually explained by chronic anovulation and therefore prolonged exposure to unopposed estrogen, and lack of progesterone activity. Progestins have been widely used to treat endometrial hyperplasia in women, however, approximately 30% of women with endometrial hyperplasia fail to respond to progesterone treatment and undergo progression to atypical hyperplasia and further transformation to EC (75). Additionally, excess androgen levels in PCOS results in increased bioavailability of unopposed estrogens due to the peripheral conversion of endogenous androgens into estrogen (6). Finally, obesity and hyperinsulinemia/insulin resistance are the two other metabolic disorders involved in PCOS that are linked to endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer. Obesity relates to high estradiol levels from aromatization of androgens in adipose tissue to estrone and conversion to estradiol (76, 77), while insulin promotes cell proliferation (78).

Insulin resistance (IR) and hyperinsulinemia has been shown to promote cell proliferation through the regulation of IGF system (78). IGF-1 and IGF-2 trigger mitogenic intracellular pathways. The expression levels of IGF-1, IGF-2 and IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R) are significantly higher in endometrial cancer than in the normal endometrium (79, 80). IGF-1R is a transmembrane tyrosine kinase, binding of which to IGF-1, IGF-2 and insulin, induces autophosphorylation. This, in turn, results in activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway, eventually promoting cell proliferation and suppressing apoptosis (81). The expression of IGF system in the endometrium of women with PCOS have been measured and compared to that in women with EC without PCOS and control women without EC or PCOS. Women with PCOS have an increased endometrial expression of genes (IGF1, IGFBP1) in endometrial tissue involved in the insulin signaling pathway compared with control women. This may explain the increased risk of EC in PCOS women (82). The expression of IGF-1 and IGFBP-1 have been further studied in decidua of PCOS patients (83). Increased expression of IGF-1 and decreased IGFBP-1 in decidua was reported PCOS patients in comparison with non-PCOS after miscarriage (83).

IGFBPs bind to IGF proteins and play a major role in the availability of IGF proteins to their receptors and therefore, enhance or attenuate proliferation of the cells, as well as the expression of IGFs. IGFBP-1 is the most abundant IGFBP in the human endometrium, primarily in the stroma (81). IGFBP-1 is mainly synthesized in the liver; however, in premenopausal women, late secretory endometrial basal cells also secrete IGFBP-1 (81). Reduced levels of IGFBP-1 have been observed in obese and hyperinsulinemic patients and therefore these patients have higher IGF availability (59, 81, 84). Thus, the insulin potentiates the proliferative action of IGFs by increasing the bioavailability of IGFs in addition to direct binding to the IGF type I receptor. Unopposed IGF-I action, like unopposed estrogen, may lead to uncontrolled endometrial proliferation and favor the development of endometrial cancer. Although these data are not specific to PCOS women, it is clear that PCOS is often associated with hyperinsulinemia/insulin resistance and one can expect that women with PCOS would exhibit similar characteristics.

While most studies are confounded by BMI and other co-morbidities prevalent in the PCOS patients, a study by Piltonen et al. showed an overexpression of inflammatory and proto-oncogenic genes, independent of body mass index, in stromal and epithelial cells of isolated endometrial cells in women with PCOS. Regardless of confounders in studies, the PCOS population is at higher risk for endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia and endometrial cancer (65).

Progesterone-based contraceptive methods are often the first line treatment for conservative management of endometrial hyperplasia in young patients who desire future fertility or older patient with multiple co-morbidities who are not good surgical candidates. Conservative treatment of endometrial hyperplasia in PCOS patients is more challenging due to the presence of progesterone resistance. Approximately 30% of women with PCOS fail to respond to progesterone therapy and progress to endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia or even worse, endometrial cancer (75). Therefore, an alternative treatment for women with PCOS and endometrial hyperplasia is needed.

Li et al reported combination of metformin and cyclic oral contraceptives as an alternative to conventional progesterone therapy to successfully reverse early stage endometrial cancer in PCOS women after 6 months of treatment (44). Metformin has been shown to have a synergic antitumor effect to progesterone on endometrial cancer cells in vitro (85). This study suggested that metformin promotes PR mRNA and protein expression in EC cell lines via activation of AMPK and inhibition of over activated mTOR pathway (44). Additionally, short-term pre-surgical treatment with metformin is described to be associated with a reduction in cellular proliferation assessed by Ki-67 proliferation index. This suggests that metformin induced reduction in Ki-67 expression and therefore cellular proliferation (86). Reduction in Ki-67 expression may be mediated by promoting phosphorylation of AMP-activated kinase and subsequent mTOR proliferative inhibition, independent of insulin and insulin-like growth factor receptor activation (86).

Insulin has also been shown to induce apoptosis in endometrial cells by activation of caspases-dependent mitochondrial apoptotic pathway (87). A recent Cochrane review on the effectiveness and safety of metformin indicated insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of metformin alone or in combination with standard therapy for endometrial hyperplasia (88). However, as discussed previously it has been shown in both in vivo and in vitro studies that metformin is of value in reversing endometrial hyperplasia and future studies may help elucidate this further.

Uterine morphology and function

Data regarding how PCOS impacts uterine morphology and function is scant. A study by Leonhardt et al. revealed no differences in myometrial morphology between PCOS and controls (89). However, uterine peristalsis in a non-pregnant uterus was less common in women with PCOS (89). Under normal conditions, uterine peristalsis is mostly active in the periovulatory period, with the dominant direction being cervicofundal, suggesting its role for sperm transportation (90, 91). Whether disturbed peristalsis contributes to infertility in PCOS is yet to be determined (89).

In a recent study in a PCOS rat model treated with daily DHEA injections, hyperandrogenized rat uterus had increased thickness due to increase in epithelial, sub-epithelial and myometrial height (92). Increased thickness in these tissues were seen as a result of alterations in cell-proliferation, collagen organization, and water absorption (92). The androgen exposure causing these uterine architecture alterations were seen to have a possible association with higher risk of developing uterine pathologies in women with PCOS (92), however such morphological changes need to be studied in hyperandrogenemic PCOS patients as well to draw further conclusions.

There is some evidence that the uterine function is different in PCOS patients in terms of pregnancy outcomes. Two meta-analyses implied that women with PCOS have significantly higher risk of preterm labor (OR 1.75) (93, 94). Data from another meta-analysis published in 2013 failed to show increased risk of preterm delivery in patient with PCOS (95). In a recent cohort study, women with PCOS and hyperandrogenemia had a shorter gestation and higher chance of preterm delivery (OR 2.28, 95% CI 1.51 – 3.45) compared with general population, whereas normoandrogenic PCOS women were not at increased risk (OR 1.35, 95% CI 0.54 – 3.39) (84). The results indicate that preterm delivery is associated with hyperandrogenemia rather than the PCOS diagnosis. Therefore further investigation on the effects of androgens on mechanisms involved in time of parturition is important. Although, progesterone and estrogen are known to be the key players in characterizing the contractility state of the pregnant myometrium and the timing and process of parturition (96), a growing body of literature in human and animal models have explored the role of androgens in mechanisms involved in cervical remodeling by boosting collagenase activity (22, 97–99) and myometrial contractility (100) and therefore determining time of delivery (99). A number of primate studies have investigated the association of androgen levels with preterm delivery. For instance, continuous administration of androstenedione to pregnant rhesus monkeys from early gestation or for a period of 48 hours during third trimester resulted in preterm initiation of myometrial contractions and cervical dilatation leading to preterm delivery (101, 102). In these studies, preterm delivery was associated with an increase in estradiol in maternal serum, suggesting conversion of androstenedione to estradiol in the placenta. However, direct administration of estrogen compounds to pregnant primates failed to result in preterm delivery (103), therefore conversion of androstenedione to estradiol is not sufficient to develop the phenotype and it is likely the androgens having a more direct effect on parturition.

In a recent rat PCOS model study, PCOS rats demonstrated more irregular uterine contractions with higher frequency and resting tone, but not amplitude of regular contractions, compared to the control group after exposure to two contractile agonists (charbacol and oxytocin) (104). These findings raise the question of whether women with PCOS have altered response to and thus success rates post induction of labor. It is clear that further investigation in the uterine morphology and function in PCOS patients are needed. For now, these interesting findings, mostly from animal models, suggest that PCOS patients may not only suffer from decreased fertility but also may have increased risk during pregnancy related to uterine alterations irrespective of metabolic parameters.

Conclusion and Future Perspectives:

PCOS is a complex and multifactorial disorder affecting around 30% of sub-fertile couples seeking treatment (105). As discussed in detail, endometrial and uterine dysfunction plays a pivotal role in PCOS related infertility and is summarized in table 1. In addition, PCOS women present with numerous endometrium-related pathologies affecting uterine health in the long term, leading to endometrial hyperplasia and cancer. Metabolic disorders associated with PCOS including, hyperandrogenism, hyperinsulinemia, and insulin resistance are postulated to be involved in disturbances in uterine morphology and function. The results of recent studies indicate that adverse endometrial changes could be reversible with anti-androgens and metformin. However, no specific treatment strategy can be recommended at this time highlighting that more studies are paramount.

Table 1.

Key points regarding PCOS and uterus molecular pathways

| Alterations in Uterine Molecular Pathways in PCOS | |

|---|---|

| Menstrual cycle dysfunction | |

| Steroid receptors in endometrium | |

| Implantation and uterine receptivity | |

| Endometrial hyperplasia | |

| Uterine morphology and function | |

Although here we discussed a great body of literature on altered endometrial biomarkers in PCOS women as well as potential treatment options, data regarding effects of PCOS on uterine morphology, function, pregnancy, and initiation and induction of labor is sparse. Thus underlying the need to address these issues in the future studies. Clearly, the uterus in PCOS deserves some more attention.

Essential Points:

PCOS affects normal uterine function, uterine receptivity and implantation

Sex steroid hormone signaling is dysregulated in the uterus of a PCOS patient

PCOS increases the risk of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer

Support:

The P.H and M.B. would like to acknowledge the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Baylor College of Medicine for research funding.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References:

- 1.Moran LJ, Hutchison SK, Norman RJ, Teede HJ. Lifestyle changes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011:CD007506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teede HJ, Misso ML, Costello MF, Dokras A, Laven J, Moran L et al. Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 2018;110:364–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azziz R, Carmina E, Chen Z, Dunaif A, Laven JS, Legro RS et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Nature reviews Disease primers 2016;2:16057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein IF, Leventhal ML. Amenorrhoea Associated with Bilateral Polycystic Ovaries. American Journal of Obstetric and Gynecology 1935;29:181–91. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fauser BCJM. Revised 2003 Consensus on Diagnostic Criteria and Long-Term Health Risks Related to Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Fertil Steril 2004;81:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexander CJ, Tangchitnob EP, Lepor NE. Polycystic ovary syndrome: a major unrecognized cardiovascular risk factor in women. Rev Obstet Gynecol 2009;2:232–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunaif A. Insulin Resistance and the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Mechanism and Implications for Pathogenesis. Endocrine Reviews 1997;18:774–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunaif A, KR S, W F, A D. Profound Peripheral Insulin Resistance, Independent of Obesity, in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Diabetes 1989;38:1165–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Setji TL, Nicole DH, Linda LS, Kathy CP, Anna Mae D, Ann JB. Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Young Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2006;91:1741–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melo AS, Ferriani RA, Navarro PA. Treatment of infertility in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: approach to clinical practice. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2015;70:765–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Legro RS, Barnhart HX, Schlaff WD, Carr BR, Diamond MP, Carson SA et al. Clomiphene, metformin, or both for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. The New England journal of medicine 2007;356:551–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Legro RS, Brzyski RG, Diamond MP, Coutifaris C, Schlaff WD, Casson P et al. Letrozole versus clomiphene for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. The New England journal of medicine 2014;371:119–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang JX, Davies MJ, Norman RJ. Polycystic ovarian syndrome and the risk of spontaneous abortion following assisted reproductive technology treatment. Hum Reprod 2001;16:2606–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rees DA, Jenkins-Jones S, Morgan CL. Contemporary Reproductive Outcomes for Patients With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Retrospective Observational Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016;101:1664–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo L, Gu F, Jie H, Ding C, Zhao Q, Wang Q et al. Early miscarriage rate in lean polycystic ovary syndrome women after euploid embryo transfer - a matched-pair study. Reproductive biomedicine online 2017;35:576–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giudice LC. Endometrium in PCOS: Implantation and Predisposition to Endocrine CA. Best Practice and Research: Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2006;20:235–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dokras A, Baredziak L, Blaine J, Syrop C, VanVoorhis BJ, Sparks A. Obstetric outcomes after in vitro fertilization in obese and morbidly obese women. Obstet Gynecol 2006;108:61–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pillay OC, Wong Te Fong LF, Crow JCE, Benjamin T, Mould W, Atiomo P et al. The Association between Polycystic Ovaries and Endometrial Cancer. Human Reproduction 2006;21:924–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niwa K, Imai A, Hashimoto M, Yokoyama Y, Mori H, Matsuda Y et al. A Case-Control Study of Uterine Endometrial Cancer of Pre- and Post-Menopausal Women. Oncology Reports 2000;7:89–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simitsidellis I, Douglas A, Gibson FL, Cousins AE-Z, Philippa TKS. A Role for Androgens in Epithelial Proliferation and Formation of Glands in the Mouse Uterus. Endocrinology 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deligdisch-Schor L. Hormone Therapy Effects on the Uterus. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 2020;1242:145–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ilicic M, Zakar T, Paul JW. The Regulation of Uterine Function During Parturition: an Update and Recent Advances. Reprod Sci 2020;27:3–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lecce G, Geri M, Magali A, Christine B, Martine P-A. Presence of Estrogen Receptor β in the Human Endometrium through the Cycle: Expression in Glandular, Stromal, and Vascular Cells. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2001;86:1379–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehasseb MK, Rina P, Anthony HT, Laurence B, Stephen CB, Marwan H. Estrogen and Progesterone Receptor Isoform Distribution through the Menstrual Cycle in Uteri with and without Adenomyosis. Fertil Steril 2011;95:2228–35.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshall E, Jacqueline L, Sheila M, Jacqueline AM, Frances C, Hilary ODC et al. In Silico Analysis Identifies a Novel Role for Androgens in the Regulation of Human Endometrial Apoptosis. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2011;96:E1746–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hung TT, Gibbons WE. Evaluation of androgen antagonism of estrogen effect by dihydrotestosterone. Journal of steroid biochemistry 1983;19:1513–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deligeoroglou EK, Creatsas GK. Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding as an Early Sign of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome during Adolescence. Minerva Ginecologica 2015;67:375–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenfield RL. Clinical review: Identifying children at risk for polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:787–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bouzas IC, Cader SA, Leao L, Kuschnir MC, Braga C. Menstrual cycle alterations during adolescence: early expression of metabolic syndrome and polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of pediatric and adolescent gynecology 2014;27:335–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.West S, Lashen H, Bloigu A, Franks S, Puukka K, Ruokonen A et al. Irregular menstruation and hyperandrogenaemia in adolescence are associated with polycystic ovary syndrome and infertility in later life: Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1986 study. Hum Reprod 2014;29:2339–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pinola P, Lashen H, Bloigu A, Puukka K, Ulmanen M, Ruokonen A et al. Menstrual disorders in adolescence: a marker for hyperandrogenaemia and increased metabolic risks in later life? Finnish general population-based birth cohort study. Hum Reprod 2012;27:3279–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Urbanska E, Hirnle L, Olszanecka-Glinianowicz M, Skrzypulec-Plinta V, Skrzypulec-Frankel A, Drosdzol-Cop A. Is polycystic ovarian syndrome and insulin resistance associated with abnormal uterine bleeding in adolescents? Ginekologia polska 2019;90:262–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maslyanskaya S, Talib HJ, Northridge JL, Jacobs AM, Coble C, Coupey SM. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: An Under-recognized Cause of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding in Adolescents Admitted to a Children’s Hospital. Journal of pediatric and adolescent gynecology 2017;30:349–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Apparao KBC. Elevated Endometrial Androgen Receptor Expression in Women with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. Biology of Reproduction 2002;66:297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Villavicencio AK, Bacallao C, Avellaira F, Gabler A, Fuentes A, Vega M. Androgen and Estrogen Receptors and Co-Regulators Levels in Endometria from Patients with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome with and without Endometrial Hyperplasia. Gynecologic Oncology 2006;103:307–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maliqueo M, Clementi M, Gabler F, Johnson MC, Palomino A, Sir-Petermann T et al. Expression of Steroid Receptors and Proteins Related to Apoptosis in Endometria of Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Fertil Steril 2003;80 (SUPPL. 2):812–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slayden OD, Nihar R, Nayak KA, Burton K, Chwalisz ST, Cameron HOD et al. Progesterone Antagonists Increase Androgen Receptor Expression in the Rhesus Macaque and Human Endometrium. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2001;86:2668–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Christopher WG, Wilson EM, Apparao KB, Lininger RA, Meyer WR, Kowalik A et al. Steroid receptor coactivator expression throughout the menstrual cycle in normal and abnormal endometrium. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2002;87:2960–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quezada S, Avellaira C, Johnson M, Gabler F, Fuentes A, Vega M. Evaluation of steroid receptors, coregulators, and molecules associated with uterine receptivity in secretory endometria from untreated women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 2006April;85:1017–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lessey BA, ALLEN PK, DEBORAH AM, HANEY AF, GREENE GL, McCARTY KS. Immunohistochemical Analysis of Human Uterine Estrogen and Progesterone Receptors Throughout the Menstrual Cycle. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 1988;67:334–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Young S, Lessey B. Progesterone Function in Human Endometrium: Clinical Perspectives. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine 2010;28:5–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leon L, Bacallao K, Gabler F, Romero C, Valladares L, Vega M. Activities of steroid metabolic enzymes in secretory endometria from untreated women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Steroids 2008;73:88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lonard DM, Kumar R, O’Malley BW. Minireview: the SRC family of coactivators: an entree to understanding a subset of polygenic diseases? Molecular endocrinology 2010;24:279–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li X, Yi F, Jin FL, Håkan B, Ruijin S. Endometrial Progesterone Resistance and PCOS. Journal of Biomedical Science 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Sabbagh M, Lam E, Brosens J. Mechanisms of endometrial progesterone resistance. . Mol Cell Endocrinol 2012;358:208–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Savaris RF, Groll JM, Young SL, DeMayo FJ, Jeong JW, Hamilton AE et al. Progesterone resistance in PCOS endometrium: a microarray analysis in clomiphene citrate-treated and artificial menstrual cycles. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:1737–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cha J, Sun X, Dey SK. Mechanisms of implantation: strategies for successful pregnancy. Nat Med 2012;18:1754–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruiz-Alonso M, David B, Carlos S. The Genomics of the Human Endometrium. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Molecular Basis of Disease 2012;1822:1931–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kajihara T, Jan JB, Osamu I. The Role of FOXO1 in the Decidual Transformation of the Endometrium and Early Pregnancy. Medical Molecular Morphology 2013;46:61–. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taylor HS, Arici A, Olive D, Igarashi P. HOXA10 Is Expressed in Response to Sex Steroids at the Time of Implantation in the Human Endometrium. Journal of Clinical Investigation 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bagot CN, Troy PJ, Taylor HS. Alteration of maternal Hoxa10 expression by in vivo gene transfection affects implantation. Gene Ther 2000;7:1378–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cermik D, Selam B, Taylor H. Regulation of HOXA-10 expression by testosterone in vitro and in the endometrium of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003January;88:238–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Buck CA, Horwitz AF. Integrin, a transmembrane glycoprotein complex mediating cell-substratum adhesion. J Cell Sci Suppl 1987;8:231–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Helfrich MH, Horton MA. Integrins and Other Adhesion Molecules. In Dynamics of Bone and Cartilage Metabolism 2006:129–51. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Franasiak JM, Holoch KJ, Yuan L, Schammel DP, Young SL, Lessey BA. Prospective assessment of midsecretory endometrial leukemia inhibitor factor expression versus alphanubeta3 testing in women with unexplained infertility. Fertil Steril 2014;101:1724–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lopes IM, Ribeiro S, Carla Cristina M, Ricardo Martins O-F, Ricardo Santos S, Manuel Jesus S et al. Histomorphometric Analysis and Markers of Endometrial Receptivity Embryonic Implantation in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome during the Treatment with Progesterone. Reproductive Sciences 2014;21:930–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.DuQuesnay R, Corrina W, Anita AA, Gordon WHS, Geoffrey H, Trew R et al. Infertile Women with Isolated Polycystic Ovaries Are Deficient in Endometrial Expression of Osteopontin but Not Avβ3 Integrin during the Implantation Window. Fertil Steril 2009;91:489–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhai J, Yao G, Wang J, Yang Q, Wu L, Chang Z et al. Metformin Regulates Key MicroRNAs to Improve Endometrial Receptivity Through Increasing Implantation Marker Gene Expression in Patients with PCOS Undergoing IVF/ICSI. Reprod Sci 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rutanen EM. Insulin-like Growth Factors in Endometrial Function. Gynecological Endocrinology : The Official Journal of the International Society of Gynecological Endocrinology 1998;12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Suikkari AM, Ruutiainen K, Erkkola R, Seppala M. Low levels of low molecular weight insulin-like growth factor-binding protein in patients with polycystic ovarian disease. Hum Reprod 1989;4:136–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang S, Kong S, Lu J, Wang Q, Chen Y, Wang W et al. Deciphering the molecular basis of uterine receptivity. Molecular reproduction and development 2013;80:8–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang H, Dey SK. Roadmap to embryo implantation: clues from mouse models. Nature reviews Genetics 2006;7:185–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yin Y, Wang A, Feng L, Wang Y, Zhang H, Zhang I et al. Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycan Sulfation Regulates Uterine Differentiation and Signaling During Embryo Implantation. Endocrinology 2018;159:2459–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Giordano MV, Giordano LA, Teixeira Gomes RC, Simões RS, Nader HB, Giordano MG et al. The Evaluation of Endometrial Sulfate Glycosaminoglycans in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Gynecological Endocrinology : The Official Journal of the International Society of Gynecological Endocrinology 2015;31:278–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Piltonen T, Chen J, Erikson D, Spitzer T, Barragan F, Rabban J et al. Mesenchymal stem/progenitors and other endometrial cell types from women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) display inflammatory and oncogenic potential. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013September;98:3765–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Germeyer A, Jauckus J, Zorn M, Toth B, Capp E, Strowitzki T. Metformin modulates IL-8, IL-1beta, ICAM and IGFBP-1 expression in human endometrial stromal cells. Reproductive biomedicine online 2011;22:327–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xiong F, Xiao J, Bai Y, Zhang Y, Li Q, Lishuang X. Metformin inhibits estradiol and progesterone-induced decidualization of endometrial stromal cells by regulating expression of progesterone receptor, cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie 2019;109:1578–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang Y, Min H, Fanci M, Xiaoyan S, Hongfei X, Jiao Z et al. Metformin Ameliorates Uterine Defects in a Rat Model of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. EBioMedicine 2017;18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jackson RL, Dockerty MB. The Stein-Leventhal Syndrome: Analysis of 43 Cases with Special Reference to Association with Endometrial Carcinoma. Obstetrical and Gynecological Survey 1957;12:574–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gallup DG, Stock RJ. Adenocarcinoma of the Endometrium in Women 40 Years of Age or Younger. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1984;64:417–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shafiee MN, Khan G, Ariffin R, Abu J, Chapman C, Deen S et al. Preventing endometrial cancer risk in polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) women: could metformin help? Gynecol Oncol 2014;132:248–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zeina H, Salman M, Atiomo W. Evaluating the Association between Endometrial Cancer and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Human Reproduction 2012;27:1327–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Matsuo K, Ramzan AA, Marc R, Gualtieri PM-F, Machida H, Moeini A et al. Prediction of Concurrent Endometrial Carcinoma in Women with Endometrial Hyperplasia. Gynecologic Oncology 2015;139:261–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fearnley EJ, Louise M, Spurdle AB, Weinstein P, Webb PM. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Increases the Risk of Endometrial Cancer in Women Aged Less than 50 Years: An Australian Case–Control Study. Cancer Causes & Control 2010;21:2303–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aghajanova L, Velarde MC, Giudice LC. Altered gene expression profiling in endometrium: evidence for progesterone resistance. Semin Reprod Med 2010;28:51–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen YL, Wang KL, Chen MY, Yu MH, Wu CH, Ke YM et al. Risk factor analysis of coexisting endometrial carcinoma in patients with endometrial hyperplasia: a retrospective observational study of Taiwanese Gynecologic Oncology Group. J Gynecol Oncol 2013;24:14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Reeves GK, Kirstin P, Valerie B, Greeb J, Spencer E, Bull D et al. Cancer Incidence and Mortality in Relation to Body Mass Index in the Million Women Study: Cohort Study. BMJ 2007;335:1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dal Maso L, Augustin L, Franceschi S, Talamini R, Polesel J, Kendall CWC et al. Association between Components of the Insulin-like Growth Factor System and Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Risk. Oncology 2004;67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Roy RN, Gerulath AH, Cecutti A, Bhavnani BR. Discordant Expression of Insulin-like Growth Factors and Their Receptor Messenger Ribonucleic Acids in Endometrial Carcinomas Relative to Normal Endometrium. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 1999;153:19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bruchim I, Sarfstein R, Werner H. The IGF Hormonal Network in Endometrial Cancer: Functions, Regulation, and Targeting Approaches. Frontiers in endocrinology 2014;5:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Navarro M, Baserga R. Limited Redundancy of Survival Signals from the Type 1 Insulin-like Growth Factor Receptor. Endocrinology 2001;142:1073–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shafiee MN, Seedhouse C, Mongan N, Chapman C, Deen S, Abu J et al. Up-regulation of genes involved in the insulin signalling pathway (IGF1, PTEN and IGFBP1) in the endometrium may link polycystic ovarian syndrome and endometrial cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2016;424:94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Luo L, Wang Q, Chen M, Yuan G, Wang Z, Zhou C. IGF-1 and IGFBP-1 in peripheral blood and decidua of early miscarriages with euploid embryos: comparison between women with and without PCOS. Gynecological endocrinology : the official journal of the International Society of Gynecological Endocrinology 2016;32:538–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Naver K, Grinsted J, Larsen S, Hedley P, Jørgensen F, Christiansen M et al. Increased risk of preterm delivery and pre-eclampsia in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and hyperandrogenaemia. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2014;121:575–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xie Y, Wang Y-l, Yu L, Hu Q, Ji L, Zhang Y et al. Metformin Promotes Progesterone Receptor Expression via Inhibition of Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (MTOR) in Endometrial Cancer Cells. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2011;126:113–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sivalingam V, McVey R, Gilmour K, Ali S, Roberts C, Renehan A et al. A Presurgical Window-of-Opportunity Study of Metformin in Obesity-Driven Endometrial Cancer. The Lancet 2015;385:S90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yasmeen A, Beauchamp M-C, Piura E, Segal E, Pollak M, Gotlieb WH. Induction of Apoptosis by Metformin in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: Involvement of the Bcl-2 Family Proteins. Gynecologic Oncology 2011;121:492–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Clement NS, Oliver TR, Shiwani H, Sanner JR, Mulvaney CA, Atiomo W. Metformin for endometrial hyperplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Leonhardt H, Gull B, Kishimoto K, Kataoka M, Nilsson L, Janson P et al. Uterine morphology and peristalsis in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Acta Radiol 2012December;53:1195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kido A, Togashi K. Uterine anatomy and function on cine magnetic resonance imaging. Reprod Med Biol 2016;15:191–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kunz G, Beil D, Deininger H, Wildt L, Leyendecker G. The dynamics of rapid sperm transport through the female genital tract: evidence from vaginal sonography of uterine peristalsis and hysterosalpingoscintigraphy. Hum Reprod 1996;11:627–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bracho GS, Altamirano GA, Kass L, Luque EH, Bosquiazzo VL. Hyperandrogenism Induces Histo-Architectural Changes in the Rat Uterus. Reprod Sci 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Boomsma CM, Eijkemans MJ, Hughes EG, Visser GH, Fauser BC, Macklon NS. A meta-analysis of pregnancy outcomes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod Update 2006;12:673–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kjerulff LE, Sanchez-Ramos L, Duffy D. Pregnancy Outcomes in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Metaanalysis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2011;204:P558.E1–.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Qin JZ, Pang LH, Li MJ, Fan XJ, Huang RD, Chen HY. Obstetric Complications in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 2013;11:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mesiano S, Welsh TN. Steroid Hormone Control of Myometrial Contractility and Parturition. Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology 2007;18:321–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sasaki K, Nakano R, Kadoya Y, Iwao M, Shima K, Sowa M. Cervical ripening with dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1982March;89:195–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ji H, Dailey T, Long V, Chien E. Androgen-regulated cervical ripening: a structural, biomechanical, and molecular analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;198:e541–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Makieva S, Saunders PT, Norman JE. Androgens in pregnancy: roles in parturition. Hum Reprod Update 2014;20:542–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Perusquía M, Navarrete E, Jasso-Kamel J, Montaño L. Androgens induce relaxation of contractile activity in pregnant human myometrium at term: a nongenomic action on L-type calcium channels. Biol Reprod 2005August;73:214–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Figueroa JP, Barbera M, Honnebier OM, Binienda Z, Wimsatt J, Nathanielsz PW. Effect of a 48-hour intravenous Δ4-androstenedione infusion on the pregnant rhesus monkey in the last third of gestation: Changes in maternal plasma estradiol concentrations and myometrial contractility. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 1989;161:481–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mecenas C, Giussani D, Owiny Jea. Production of premature delivery in pregnant rhesus monkeys by androstenedione infusion. Nat Med 1996;2:443–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Novy MJ, Walsh SW. Dexamethasone and estradiol treatment in pregnant rhesus macaques: Effects on gestational length, maternal plasma hormones, and fetal growth. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 1983;145:920–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sajadi M, Noroozzadeh M, Bagheripour F, Ramezani Tehrani F. Contractions in the Isolated Uterus of a Rat Model of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Compared to Controls in Adulthood. International journal of endocrinology and metabolism 2018;16:e63135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Barthelmess E, Naz R. Polycystic ovary syndrome: current status and future perspective. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2014January;1:104–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]