Abstract

Typical carcinoid tumors of the lungs carry an excellent prognosis after complete surgical excision. However, recurrence of these cancers remains poorly described in the literature and may occur many years after surgery.

We report a case of carcinoid tumor of the lung. Clinical presentation and follow-up were uneventful.

The 55 years old patient had got a surgical removal of a huge typical carcinoid tumor of the left lung. A left pneumonectomy with a mediastinal lymph node resection were performed. Thirteen years later, paraneoplastic acromegaly revealed a pulmonary and extrapulmonary recurrence of the tumor. We prescribed a chemotherapy regimen including Cisplatin and Etoposide.

Endocrine paraneoplastic syndromes are related to mutations in specifically known genes. Several mutations may become a promising therapeutic target in the future. In the case of neuro-endocrine pulmonary tumors, authors described BCOR gene mutation as an oncogenic development inducer and an eventual generator of ectopic tumoral secretions.

The more we get familiar with carcinoid tumor mutations, the closer we get to targeted therapy for non-resectable tumors.

Keywords: Carcinoid tumor, Recurrence, Paraneoplastic syndrome, Acromegaly

1. Background

Twenty-five percent of carcinoid tumors are pulmonary in origin and comprise as much as 5% of all primary lung tumors [1]. They are summarily classified as either typical or atypical by histopathologic examination. As much as 90% of tumors are typical [2,3].

The invasive metastatic potential of pulmonary carcinoid tumors is well known. Atypical carcinoid tumors metastasize from 27 to 66% to the lymph node while typical carcinoid (TC) tumors metastasize in 2–11% [4]. Further distant metastases are rare in both cases [5]. Resectable carcinoid tumors carry an excellent prognosis after complete surgical excision. However, local or distant recurrence of these cancers remains poorly described in the literature and may occur many years after surgery. The management of the metastatic stage is not currently standardized due to a lack of relevant studies. Usually, atypical carcinoids are more aggressive with a higher incidence of distant metastases [6]. The overall 5-year survival rate for TC is around 90–100% but much worse for atypical carcinoids (40–93% depending on the series).

We report a case of a carcinoid tumor of the lung. Clinical presentation and follow-up were uneventful.

2. Case report

The patient was a 55-year-old man current smoker. He underwent a left pneumonectomy with lymph node resection in 2007 for a huge tumor of the left lower lobe. The pathological examination found a typical carcinoid tumor of 8 cm long axis of the left lower lobe with minimal infiltration of the upper lobe, pulmonary and lymph node caseo-follicular tuberculosis. Hilar and mediastinal lymph node examination had shown no metastasis.

A histological diagnosis of bronchial carcinoid tumor was made. No adjuvant chemotherapy was undergone. Pulmonary tuberculosis was treated using a six-months-lasting oral quadritherapy including Isoniazid, Rifampicin, Pyrazinamide, and Ethambutol. Clinical and radiological follow-up for ten years had shown no recurrence sign. The patient presented in 2019 an intense lumbar squeezing pain progressively worsened, not relieved after using Paracetamol or Ibuprofen. Our patient noted also crural electrical discharges when he walked.

On examination, there were new obvious signs detected on sight: protruding lower jaw and brow, an enlarged nose, thickened lips, coarse fingers and toes (Fig. 1). Acromegaly was recognized and we suspected a paraneoplastic mechanism. We detected on examination also, the presence of a left paravertebral swelling at the level of T 12, quite painful on palpation.

Fig. 1.

Obvious signs detected on sight: protruding lower jaw, an enlarged nose, thickened lips, Olympian forehead and protrusive eyebrow arches.

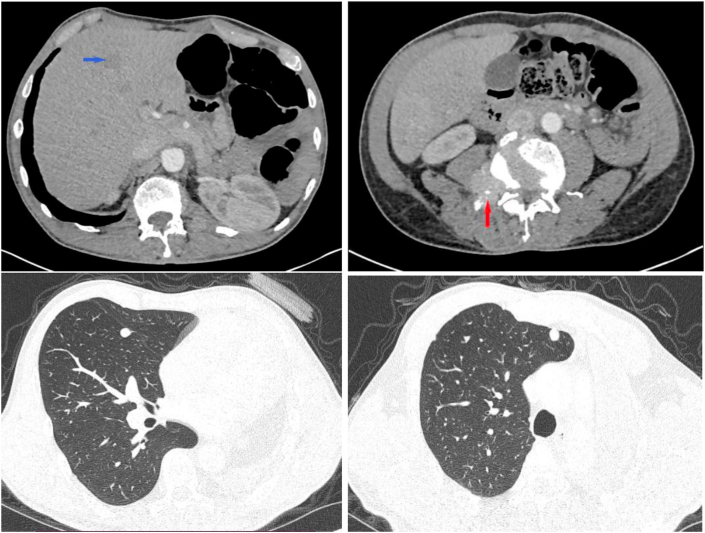

A whole-body scanner was requested. It has shown a left pneumonectomy with a free right bronchial stump, diffuse dense right pulmonary nodules of different sizes. The largest nodule sits at the ventral segment of the right upper lobe and measures 13mm. We spotted multiple osseous lesions concerning the posterior arch of the 12th left rib with extension to the soft parts, the right side of the third lumbar vertebra, and into the medullary canal (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Hypodense liver metastatic nodule (blue arch), lesion in the right side of the third lumbar vertebra reaching the medullary canal (red arch), left pneumonectomy with diffuse right pulmonary dense nodules. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

CT scan had shown also multiple hypodense liver nodules, the greatest of which sized 21 mm in diameter, osteocondensing lesions of the skull, which sit at the frontal bone and the left parietal bone.

A biopsy of the hepatic nodule by echo-guided route was performed, concluding with a secondary localization of a typical carcinoid tumor (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Malignant epithelial proliferation arranged in cords within a thin fibro-vascular stroma (A). Cells Immunostaining revealed Synaptophysin and Chromogranin (B).

Oral route morphine was prescribed to get sufficient spinal analgesia. Palliative chemotherapy based on Cisplatin and Etoposide was started. After having received four cycles of chemotherapy, a body CT scan compared to the first imaging findings concluded to stability of the tumor volume. There was no regression of the paraneoplastic signs after chemotherapy. The patient is alive nowadays after a follow-up of 14 months.

3. Discussion

An analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program of the National Cancer Institute noted an increased incidence of pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors in the last decades, especially for TC [7].

This trend could be just secondary to increased precision in pathological diagnostic tools. Bronchial TC usually occurs in the fifth decade, a younger age compared with other high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms. There is an equal distribution between genders, even if, in younger patients with TC, women are affected twice more than men.

There is no clear correlation between pulmonary carcinoid tumors and smoking habits. Only a minority of patients with TC had a smoking history and usually with low smoking index [8].

Neurological or neuro-endocrine para-neoplastic syndromes were noted in neuro-endocrine type tumors. Published cases presented with Cushing syndrome, limbic encephalitis and Guillain-Barre-like syndrome [[9], [10], [11]]. A paraneoplastic syndrome associated with a pulmonary TC is rare. Hypothalamo-pituitary axis was involved in one case which presented with TC of the lung and Cushing syndrome [12]. The paraneoplastic syndrome was precisely an ectopic ACTH secretion in the tumor. The index case had a specific missense mutation of BCOR gene: mRNA coding carried a shifting change with Serine amino-acid in the position 1240 which turned to be Cysteine. BCOR gene codes a protein known as the transcription corepressor of BCL6 gene. The mutation can impact cell apoptosis involving certain immune system cells. Authors assumed it could induce pituitary hormones secretion. A study by Tibery et al. proved BCL6/BCOR/SIRT1 complex as the repressor of the Sonic Hedgehog pathway (SHH) in normal and oncogenic neural development [13]. SHH signaling pathway is a major regulator of cell differentiation, cell proliferation, and tissue polarity. Aberrant activation of the SHH pathway has been shown in a variety of solid cancers [14].

On the other hand, paraneoplastic acromegaly was described in pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors [15]. Laboratory tests revealed markedly increased growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) without GHRH elevation. Knowing all pituitary hormones have one precursor, we can assume that one genetic aberration leads to those neuro-endocrine paraneoplastic syndromes.

A non-negligible fraction of bronchial carcinoids evolves metastatically, most often at the locoregional level with lymph node invasion but also extrathoracic localizations occur in 7–18% of cases depending on the series [16]. Metastatic evolution can be very late and appear years, even decades after total exeresis of the primary. For inoperable or metastatic patients, the therapeutic attitude is similar to that applied for digestive TC. Few prospective studies have been conducted concerning this tumor subtype and there is no consensual chemotherapy protocol. The efficiency and the contribution of chemotherapy for advanced neuroendocrine tumors remain debated [17].

Chemotherapy should only be offered in the case of a benefit/risk balance evaluated well thought. A Mono- or polychemotherapy regimen could be performed. Agents such as doxorubicin, 5-fluorouracil (5FU), dacarbazine, cisplatin, etoposide, streptozotocin have shown modest effects [[18], [19], [20], [21]].

Usually, physicians do not verify BCOR gene mutation in neuroendocrine tumors. Studying BCOR gene mutation in a therapeutic intent is a promising hypothesis. So far, targeted therapy of TC is still groping. The SHH signaling pathway is highly complex that has been shown to play important roles in promoting oncogenesis, tumor growth and progression, and tumor drug resistance [14]. Therefore, several components of the SHH pathway are viable therapeutic targets for anti-cancer therapies [14].

4. Conclusions

Bronchial CT are rare tumors with heterogeneous evolution and metastatic potential in 6–18% of cases when discovered or essentially after treatment. Given the rarity of the tumor, there are few specific data in the literature. Long-term survival of several years can therefore be observed even in metastatic patients with a good quality of life, as these two observations illustrate. Close surveillance may lead to earlier detection and treatment of recurrences, improving overall outcomes.

Consent for publication

A written consent for publication was obtained from the patient.

Funding

None.

Declaration of competing interest

Interests related to the manuscript theme: None.

Acknowledgement

None.

References

- 1.Thomas C.F., Tazelaar H.D., Jett J.R. Typical and atypical pulmonary carcinoids: outcome in patients presenting with regional lymph node involvement. Chest. 2001;119(4):1143–1150. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.4.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fjällskog M.-L.H., Janson E.T., Falkmer U.G., Vatn M.H., Öberg K.E., Eriksson B.K. Treatment with combined streptozotocin and liposomal doxorubicin in metastatic endocrine pancreatic tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2008;88(1):53–58. doi: 10.1159/000117575. https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/117575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.García-Yuste M., Matilla J.M., Cueto A., Paniagua J.M.R., Ramos G., Cañizares M.A. Typical and atypical carcinoid tumours: analysis of the experience of the Spanish multi-centric study of neuroendocrine tumours of the lung. Eur. J. Cardio. Thorac. Surg. Off. J. Eur. Assoc. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2007;31(2):192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moertel C.G., Johnson C.M., McKusick M.A., Martin J.K., Nagorney D.M., Kvols L.K. The management of patients with advanced carcinoid tumors and islet cell carcinomas. Ann. Intern. Med. 1994;120(4):302–309. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-4-199402150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forde P.M., Hooker C.M., Boikos S.A., Petrini I., Giaccone G., Rudin C.M. Systemic therapy, clinical outcomes, and overall survival in locally advanced or metastatic pulmonary carcinoid: a brief report. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2014;9(3):414–418. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steuer C.E., Behera M., Kim S., Chen Z., Saba N.F., Pillai R.N. Atypical carcinoid tumor of the lung: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database analysis. J. Thorac. Oncol. Off. Publ. Int. Assoc. Stud. Lung Canc. 2015;10(3):479–485. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Modlin I.M., Sandor A. An analysis of 8305 cases of carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 1997;79(4):813–829. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970215)79:4<813::aid-cncr19>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sachithanandan N., Harle R.A., Burgess J.R. Bronchopulmonary carcinoid in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Cancer. 2005;103(3):509–515. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20825%20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richa C.G., Saad K.J., Halabi G.H., Gharios E.M., Nasr F.L., Merheb M.T. Case-series of paraneoplastic Cushing syndrome in small-cell lung cancer. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. Case Rep. 2018;2018:1. doi: 10.1530/EDM-18-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kacem M., Belloumi N., Bachouche I., Mersni M., Chermiti Ben Abdallah F., Fenniche S. Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis revealing a small cell carcinoma of the lung. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2018;26:157–160. doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2018.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung I., Gurzu S., Balasa R., Motataianu A., Contac A.O., Halmaciu I. A coin-like peripheral small cell lung carcinoma associated with acute paraneoplastic axonal Guillain-Barre-like syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94(22) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000910. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4616354/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Y., Yue L., Li J., Yuan M., Chai Y. Cushing's syndrome secondary to typical pulmonary carcinoid with mutation in BCOR gene: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96(34) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tiberi L., Bonnefont J., van den Ameele J., Le Bon S.-D., Herpoel A., Bilheu A. A BCL6/BCOR/SIRT1 complex triggers neurogenesis and suppresses medulloblastoma by repressing sonic Hedgehog signaling. Canc. Cell. 2014;26(6):797–812. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rimkus T.K., Carpenter R.L., Qasem S., Chan M., Lo H.-W. Targeting the sonic Hedgehog signaling pathway: review of smoothened and GLI inhibitors. Cancers (Basel) 2016;8(2) doi: 10.3390/cancers8020022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krug S., Boch M., Rexin P., Pfestroff A., Gress T., Michl P. Acromegaly in a patient with a pulmonary neuroendocrine tumor: case report and review of current literature. BMC Res. Notes. 2016;9:326. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-2132-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouvier N., Zengerling V., Halley A., Le Pennec V., Le Rochais J.P., Madelaine J. Carcinoïde bronchique d’emblée multimétastatique et survie prolongée. Rev. Mal. Respir. 2007;24(1):63–68. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S076184250791013X [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phan A.T., Öberg K., Choi J., Harrison L.H., Hassan M.M., Strosberg J.R. NANETS consensus guideline for the diagnosis and management of neuroendocrine tumors: well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors of the thorax (includes lung and thymus) Pancreas. 2010;39(6):784–798. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ec1380. http://journals.lww.com/00006676-201008000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beasley M. Pulmonary atypical carcinoid: predictors of survival in 106 cases. Hum. Pathol. 2000;31(10):1255–1265. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2000.19294. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0046817700430248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Granberg D., Eriksson B., Wilander E., Grimfjärd P., Fjällskog M.-L., Öberg K. Experience in treatment of metastatic pulmonary carcinoid tumors. Ann. Oncol. 2001;12(10):1383–1391. doi: 10.1023/a:1012569909313. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0923753419543307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chong C.R., Wirth L.J., Nishino M., Chen A.B., Sholl L.M., Kulke M.H. Chemotherapy for locally advanced and metastatic pulmonary carcinoid tumors. Lung Canc. 2014;86(2):241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.08.012. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0169500214003572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forde P.M., Hooker C.M., Boikos S.A., Petrini I., Giaccone G., Rudin C.M. Systemic therapy, clinical outcomes, and overall survival in locally advanced or metastatic pulmonary carcinoid: a brief report. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2014;9(3):414–418. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000065. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1556086415302264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]