Abstract

Human rhinovirus (HRV) is one of the most important cold-causing pathogens in humans. Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) are a recently discovered class of small non-coding RNAs whose best-understood function is to repress mobile element (ME) activity in animal germline. However, the profile of human/host piRNA during HRV infection is largely unknown. Here we performed high-throughput sequencing of piRNAs from H1-HeLa cells infected with HRV16 at 12 h, 24 h, and 36 h. The results showed that 22,151,664, 24,362,486 and 22,726,546 piRNAs displayed differential expression after HRV16 infection for three time points. A significant differential expression of 21 piRNAs was found in all time points and further verified by RT-qPCR, including 7 known piRNAs and 14 newly found piRNAs. In addition, piRNA prediction was performed on Piano using the SVM algorithm and transposon information. It found that novel_pir78110, novel_pir78107, novel_pir78097, novel_pir78094 and novel_pir76584 are associated with the DNA/hobo of Drosophila, Ac of maize and Tam3 of snapdragon (hAT)-Charlie transposon. The novel_pir97924, novel_pir105705 and novel_pir105700 recognize long interspersed nuclear elements 1 (LINE-1). The novel_pir33182 and novel_pir46604 are related to the long terminal repeat (LTR)/(Endogenous Retrovirus1) ERV1 repetitive element. The novel_pir73855 is related to the LTR/ERVK repetitive element. Both novel_pir70108 and novel_pir70106 are associated with the LTR/ERVL-MaLR repetitive element. The novel_pir15900 is associated with the DNA/hAT-Tip100 repetitive element. Overall, our results indicated that rhinovirus infection could reduce the expression of some piRNAs to facilitate upregulation of LINE-1 transcription or retrotransposons' expression, which is helpful to further explore the mechanism of rhinovirus infection.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12250-021-00344-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Human rhinovirus (HRV), Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), Small non-coding RNAs, Virus infection

Introduction

Small RNAs can be categorized into three types based on their structures, origin, processing factors and the Argonaute proteins to which they bind, including microRNA (miRNA), small interfering RNA (siRNA), and Piwi-interacting RNA (piRNA) (Lipovich et al. 2010; Hombach and Kretz 2016). Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) are a class of small non-coding RNAs containing 25–31 nucleotides in length (Aravin et al. 2006; Girard et al. 2006; Sarkar et al. 2017). piRNAs are distinguished from microRNAs by being slightly longer, mainly expressed in the germline and binding to Piwi-class opposed to Ago-class Argonaute proteins (Aravin et al. 2006; Girard et al. 2006; Siomi et al. 2011). piRNAs are initially found to bind to Piwi family proteins to form Piwi/piRNA complexes. These complexes play important biological functions in the silencing of transposons, maintenance of genome stability and integrity in germ cells, regulation of germ cell development and differentiation, and formation of gametes (Rouget et al. 2010; Huang et al. 2013; Gou et al. 2015). Previous studies show that Piwi/piRNA complexes epigenetically and post-transcriptionally silence transposable elements in germline stem cells (Aravin and Bourc’his 2008; Aravin et al. 2008; Kuramochi-Miyagawa et al. 2008; Ku and Lin 2014). Furthermore, piRNAs are associated with the development and progression of several types of cancers (Cheng et al. 2011, 2012; Cui et al. 2011). A study has found that piRNA-823 in extracellular vesicles is associated with the production of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its proangiogenic activity in multiple myeloma cells (Yan et al. 2015; Li et al. 2019). Recent studies indicate that piRNAs play a vital role in physiological and pathological processes at the transcriptional or post-transcriptional level through piRNAs/piwi complex-mediated transcriptional gene silencing (TGS) and post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) (Liu et al. 2019). The piRNAs/piwi complex directly binds with some proteins by piRNAs or the piwi protein PAZ domain to facilitate multi-protein interactions or to alter their subcellular localization (Liu et al. 2019).

Human rhinovirus (HRV) is one of the most important cold-causing pathogens in humans. HRV causes 50% or more upper respiratory tract infections and is the primary pathogen of acute lower respiratory tract infection in children. HRV is not only a key inducer of pediatric asthma (Stenberg-Hammar et al. 2017), but also associated with aggravation of acute exacerbations of chronic lung diseases, including asthma, bronchiectasis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (Gunawardana et al. 2014; Dijkema et al. 2016; Miller et al. 2016; Makris and Johnston 2018). However, the pathogenesis of HRV is unclear entirely. Whether piRNAs change during the HRV infection or whether piRNAs participates in the HRV pathogenesis remains unclear. Here we performed high-throughput sequencing on piRNAs of H1-HeLa cells infected with HRV16 at 12 h, 24 h and 36 h post-infection (p.i). Differential expression piRNAs were identified, their locations and functions were further predicted. Our data provide important insights into the interactions between piRNAs and HRV16 infection.

Materials and Methods

Cell and Virus

HRV16 strain (ATCC® VR-283™) was propagated at MOI of 5 in H1-HeLa cells with 2% serum for maintenance and infection. H1-HeLa cells were purchased from American type culture collection (ATCC) and maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and antibiotics. Cells were harvested and analyzed at 12 h, 24 h, and 36 h p.i.

RNA Extraction

RNA was extracted from H1-HeLa cells infected with HRV16 at 12 h, 24 h, 36 h p.i and no-infected H1-HeLa cells through Trizol methods. For each sample, we subjected three micrograms (μg) of total RNA to PO treatment (Kirino and Mourelatos 2007). Total RNA (3 μg) and NaIO4 (10 mmol/L) were mixed and kept at 0 °C for 40 min, then 5 μL of 1 mol/L rhamnose was added to quench the unreacted NaIO4 at 0 °C for 30 min. Fifty-five μL of 2 mol/L Lys-HCl (pH 8.5) was then added and the mixture was incubated at 45 °C for 90 min for β-elimination. The treated RNAs were purified using a standard isopropanol precipitation method.

High-Throughput Sequencing

Small RNA (sRNA) library was constructed using the SOLiD Small RNA Expression Kit (Ambion). First, sRNAs were ligated to the 5′ and 3′ adaptors, and then reverse transcribed into cDNAs. A small amount of RNase was added to the cDNAs to remove any untranscribed RNAs. The cDNAs were amplified by PCR to obtain sufficient high-quality cDNAs for the construction of the sequencing library. After the library was constructed, the quality of the library was assessed using Bioanalyzer 2100, and the library was then sequenced using high-throughput sequencing. A substantial amount of sRNA sequences (16–31 nt) were obtained after removal of linkers and low-quality data. Most of these sRNAs were 22 nt in length, which is the typical length of sRNA generated from the Dicer pathway, and are hence well-conserved. After the removal of < 18 nt sequences, the final total purified sequences were used for piRNAs analysis.

piRNA Analysis of Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Approximately 1.5 × 104 cells were inoculated with HRV16 (MOI = 5) in a 96-well cell culture plate. Infected or uninfected cells of three repetitive wells were collected at 12 h, 24 h, and 36 h. Total cellular RNA of each well was isolated with Trizol Reagent. cDNAs of 21 piRNAs were gotten using stem-loop RT primers. The specific forward primer of each piRNA and a universal reverse primer were used to quantitatively analyze the expression of piRNAs on CFX96 (Bioread USA) using U6 small nuclear RNA (U6 snRNA) as a control. The relative amount of expressed piRNA was also calculated by the log2 conversion of 2−△△Ct.

Data Analysis

The sequencing data of the four samples were analyzed in this study through TPM (Transcripts Per Kilobase Million). Comparable data were obtained by determining non-redundant sequences and copy number. piRNA prediction was performed on Piano using the SVM algorithm and transposon information (Wang et al. 2014). Genome distributions of piRNAs were produced by filtering reads with a length of 25–31 nts respectively and mapping the genome positions of the 5′ end of each read. Known piRNAs were verified by the Bowtie software with piRBase, and the secondary structure/folding of new piRNA sequences was predicted using UNAFold. The expression of piRNAs was normalized and compared using the t-test. The differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. Differential gene expression analysis based on the negative binomial distribution was performed using DESeq2 as described (Love et al. 2014). We use adjusted P-value ≤ 0.1 and the absolute value of Log2Ratio ≥ 1 as the default threshold to judge the significance of gene expression difference. Heatmap of piRNAs, which concurrently expressed among H1-HeLa cells at 12 h, 24 h and 36 h p.i, was generated by MultiExperiment Viewer.

Results

Overall Difference in piRNAs Expression between Control and HRV16-Infected H1-HeLa Cells

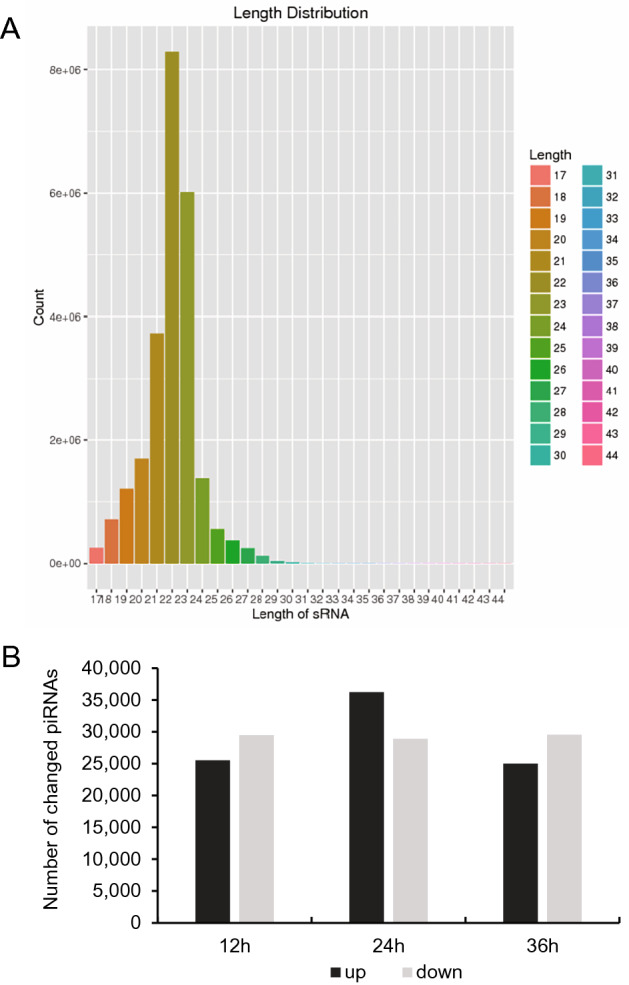

To determine the overall differences in piRNA type and expression, we compared the common and unique piRNA sequences among H1-HeLa cells at 12 h, 24 h, and 36 h p.i. The results not only exhibited the typical size distribution of small ncRNAs (around 25–31 nts) (Fig. 1A), but also showed signatures of 5′1U and 10A biases as reported (Miesen et al. 2016a; Leggewie and Schnettler 2018), suggesting that both primary and secondary piRNAs produced when H1-HeLa cells were infected with HRV16. Compared with normal control cells, there were 25,523 of total 22,151,664, 36,229 of total 24,362,486 and 25,009 of total 22,726,546 upregulated piRNAs, and 29,472 of total 22,151,664, 28,906 of total 24,362,486 and 29,541 of total 22,726,546 downregulated piRNAs in H1-HeLa cells at 12 h, 24 h and 36 h p.i, respectively (Fig. 1B, Supplementary Table S1). In particular, the infected H1-HeLa cells had 35,264 upregulated and 25,855 downregulated piRNAs at 24 h p.i compared with 12 h p.i; 25,564 upregulated and 26,782 downregulated piRNAs at 36 h p.i compared with 12 h p.i; and 25,268 upregulated and 34,172 downregulated piRNAs at 36 h p.i compared with 24 h p.i.

Fig. 1.

Overall difference in piRNA expression among HRV16-infected H1-HeLa cells. A The overall nucleotide length distribution of RNA-sequencing results. B Upregulated and downregulated piRNAs in H1-HeLa cells at 12 h, 24 h and 36 h post-HRV16 infection. Black column indicates upregulated piRNAs. Grey column indicates downregulated piRNAs.

HRV16 Infection Induces piRNAs Changes in H1-HeLa Cells at Different Time Points Post Infection

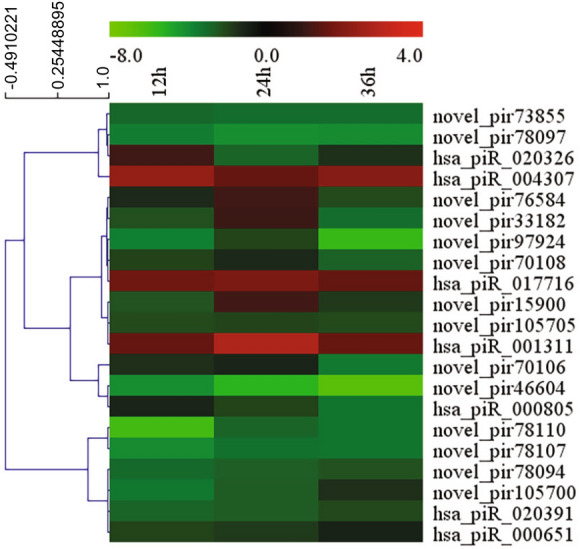

To screen for piRNAs induced from HRV16 infection, differentially expressed piRNAs at different time points post infection were analyzed. The expression of piRNAs was normalized by the filtering of known and highly-homologous sequences. Normalized piRNAs with a log2 ratio < 1 were removed. Compared with normal control cells, 120, 99 and 165 piRNAs were differentially expressed in H1-HeLa cells at 12 h, 24 h and 36 h p.i, respectively (Supplementary Table S2). In particular, 87 piRNAs were differentially expressed at 24 h p.i compared with 12 h p.i (Supplementary Table S3); 170 piRNAs were differentially expressed at 36 h p.i compared with 12 h p.i (Supplementary Table S3), and 174 piRNAs were differentially expressed at 36 h p.i compared with 24 h p.i (Supplementary Table S3). Our results showed that the expression of 21 piRNAs was concurrently changed among H1-HeLa cells at 12 h, 24 h and 36 h p.i (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Heatmap of 21 piRNAs concurrently expression among H1-HeLa cells at 12 h, 24 h and 36 h p.i by MultiExperiment Viewer.

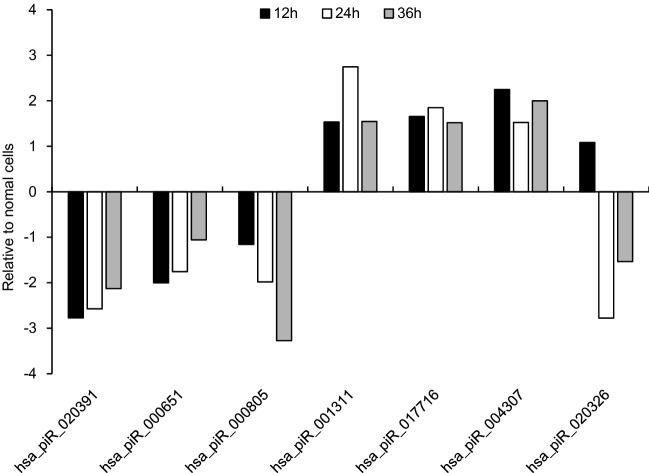

Of these 21 piRNAs, seven piRNAs expression was significantly changed at the three infection time points, which have been reported in piRBase. The overall expression of hsa_piR_020391, hsa_piR_000805 and hsa_piR_000651 was downregulated relative to normal cells. Three of these piRNAs were higher than normal cells, which were respectively hsa_piR_017716, hsa_piR_004307 and hsa_piR_001311 (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the expression of has_piR_020326 was upregulated at 12 h p.i but downregulated from 1.49 to -2.38 and -1.18 compared with normal cells (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The RNA-sequencing result of seven known piRNAs expression levels in HRV16-infected H1-HeLa cells at the 12 h, 24 h and 36 h post-infection.

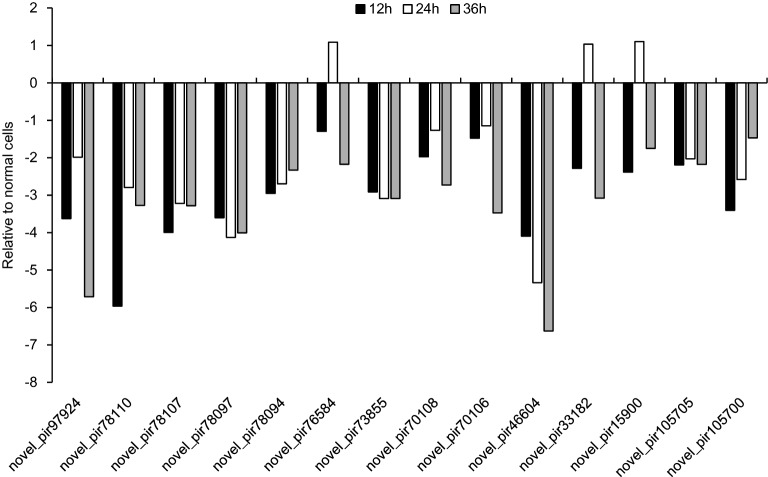

Our results also found that 14 new piRNAs were differently expressed in infected-H1-HeLa cells relative to normal H1-HeLa cells at 12 h, 24 h and 36 h p.i. These new piRNAs were named as novel_pir97924, novel_pir78110, novel_pir78107, novel_pir78097, novel_pir78094, novel_pir76584, novel_pir73855, novel_pir70108, novel_pir70106, novel_pir46604, novel_pir33182, novel_pir15900, novel_pir105705, and novel_pir105700, respectively. After the expression of these piRNA transcripts in infected H1-HeLa cells relative to normal cells was calculated, we found that the overall expression of these new piRNAs was downregulated, except novel_pir78107, novel_pir76584, novel_pir70106, which were slightly upregulated at 24 h p.i (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The RNA-sequencing result of 14 new piRNAs expression levels in HRV16-infected H1-HeLa cells at the 12 h, 24 h and 36 h post-infection.

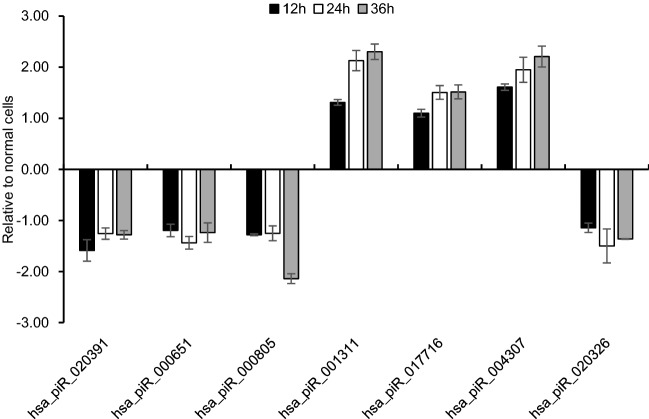

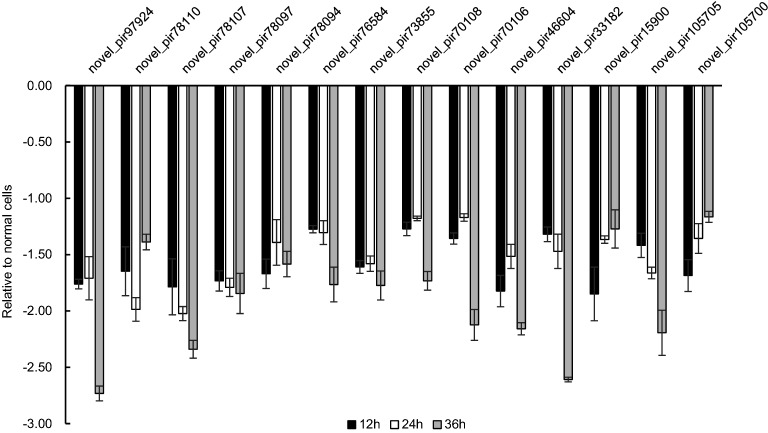

Validation of Differentially Expressed piRNAs by RT-qPCR

To confirm the expression of above piRNAs identified by sequencing, we performed stem-loop RT-qPCR to examine the expression of those piRNAs in HRV16-infected H1-HeLa cells. Of these seven piRNAs, hsa_piR_001311, hsa_piR_004307 and hsa_piR_017716, appeared trend of upregulation at 12 h, 24 h and 36 h p.i (Fig. 5). Expression of hsa_piR_004307 upregulated continuously over 1.5-fold as high as that of normal cells at 12 h, 24 h and 36 h p.i (Fig. 5). Expression of hsa_piR_001311 and hsa_piR_017716 reached over 1.5-fold of normal cells at 24 h and 36 h p.i. However, expression of hsa_piR_020391, hsa_piR_000651, hsa_piR_000805, and hsa_piR_020326 were lower than normal cells and present a trend of downregulation at 12 h, 24 h and 36 h p.i (Fig. 5). The results showed that changes in piRNAs expression levels were consistent with RNA-seq data. Similarly, we also examined the expression of 14 new piRNAs using stem-loop RT-qPCR in HRV16-infected H1-HeLa cells. Of these novel piRNAs, similar to high-throughput results, the expression of all novel piRNAs was lower than normal cells at 12 h, 24 h and 36 h p.i (Fig. 6). The fold-change of expression level of new piRNAs that compared to normal cells were shown in Table 2.

Fig. 5.

The expression of seven known piRNAs in HRV16-infected H1-HeLa cells at 12 h, 24 h and 36 h p.i. was validated by RT-qPCR. The infected and normal cells of three repetitive wells were collected at 12 h, 24 h, and 36 h post-infection. Total cellular RNA of each well was isolated with TRIzol Reagent. cDNAs of piRNAs were gotten using stem-loop RT primers. RT-qPCR was performed using specific forward primer of each piRNA and a universal reverse primer. U6 was used as an endogenous control for data normalization. The relative amount of expressed mRNA was calculated by the log2 conversion of 2−△△Ct.

Fig. 6.

The expression of new piRNAs in HRV16-infected H1-HeLa cells at 12 h, 24 h and 36 h p.i. was validated by RT-qPCR. The infected and normal cells of three repetitive wells were collected at 12 h, 24 h, and 36 h post-infection. Total cellular RNA of each well was isolated with TRIzol Reagent. cDNAs of piRNAs were gotten using stem-loop RT primers. RT-qPCR was performed using specific forward primer of each piRNA and a universal reverse primer. U6 was used as an endogenous control for data normalization. The relative amount of expressed mRNA was also calculated by the log2 conversion of 2−△△Ct.

Table 2.

Characteristics of 14 novel piRNAs in the H1-HeLa cells.

| piRNA id | Chromosome | Repeat family | Strand | Start | End | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| novel_pir97924 | chr8 | LINE/L1 | − | 136,785,683 | 136,786,238 | GGGGGGCCCAAGTCCTTCTG |

| novel_pir78110 | chr3 | DNA/hAT-Charlie | − | 61,684,855 | 61,685,144 | CCACCCTGAACGCGCCCGA |

| novel_pir78107 | chr3 | DNA/hAT-Charlie | − | 61,684,855 | 61,685,144 | ACCACCCTGAACGCGCCCGA |

| novel_pir78097 | chr3 | DNA/hAT-Charlie | − | 61,684,855 | 61,685,144 | TACCACCCTGAACGCGCCCGA |

| novel_pir78094 | chr3 | DNA/hAT-Charlie | − | 61,684,855 | 61,685,144 | TACCACCCTGAACGCGCCCG |

| novel_pir76584 | chr3 | DNA/hAT-Charlie | − | 31,021,593 | 31,021,781 | GTTGGGACAAAAAAAAAA |

| novel_pir73855 | chr3 | LTR/ERVK | − | 15,779,666 | 15,780,942 | TTCTGGGCTGTAGTGCGCTA |

| novel_pir70108 | chr2 | LTR/ERVL-MaLR | − | 12,439,669 | 12,440,139 | GGTTGGGAAAAAAAAAAAA |

| novel_pir70106 | chr2 | LTR/ERVL-MaLR | − | 12,439,669 | 12,440,139 | GGTTGGGAAAAAAAAAAAAA |

| novel_pir46604 | chr18 | LTR/ERV1 | − | 68,878,785 | 68,880,277 | GGGCGGCGGGGCGGGGCGG |

| novel_pir33182 | chr14 | LTR/ERV1 | + | 102,706,661 | 102,707,085 | TCCCGGGTTTCGGCACCAAA |

| novel_pir15900 | chr11 | DNA/hAT-Tip100 | + | 62,126,034 | 62,126,618 | TGGTTAGCACTCTGGACT |

| novel_pir105705 | chrX | LINE/L1 | + | 121,106,366 | 121,108,397 | ACGTAGCAGAGCAGCTCCCTCGC |

| novel_pir105700 | chrX | LINE/L1 | + | 121,106,366 | 121,108,397 | TACGTAGCAGAGCAGCTCCCTCGC |

Prediction of piRNAs and Functional Analyses

piRNA prediction was performed using Piano (Wang et al. 2014), and known piRNAs were verified by the Bowtie software. Secondary structure/folding of new piRNA sequences were predicted by UNAFold. The chromosome (chr) location of seven piRNAs was analyzed through piRBase. We found that hsa_piR_004307 and hsa_piR_020391 were located on chr 10 and 18, respectively. hsa_piR_001311 was located on chr 1 and 3, hsa_piR_020326 was located on chr 2, 8 and 9. Interesting, hsa_piR_020326 recognized 6 sequences of chr 9. hsa_piR_001311 recognized two sequences of chr 1. hsa_piR_017716, hsa_piR_000805 and hsa_piR_000651 are located on chr 15. hsa_piR_000805 was also located on chr 13 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of seven known piRNAs in the H1-HeLa cells.

| piRNA id | Chomosome | Strand | Start | End | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa_piR_020391 | chr18 | − | 11,644,914 | 11,644,943 | UGGUGAGAACUGACAAAUGUGGUAGGUGGU |

| hsa_piR_000651 | chr15 | − | 20,649,047 | 20,649,074 | ACCAAACCCAUUCUCCCAUCAGUGCUGC |

| hsa_piR_000805 | chr15 | + | 60,329,537 | 60,329,567 | ACCUAGGACUUGACCAAGGCCACAGCCAGGU |

| chr13 | + | 130,067,407 | 130,067,437 | ||

| hsa_piR_001311 | chr1 | − | 16,745,061 | 16,745,089 | AUUGGUGGUUCAGUGGUAGAAUUCUCGCC |

| chr1 | + | 17,061,005 | 17,061,033 | ||

| chr3 | + | 15,524,505 | 15,524,533 | ||

| hsa_piR_017716 | chr15 | + | 49,375,486 | 49,375,517 | UGGAUUUCCAGAAGCUGCUUGAUGAUUCUUCC |

| hsa_piR_004307 | chr10 | + | 126,301,128 | 126,301,156 | UCCAAAUCGUUCCUUGGGCCCGAGACUCC |

| hsa_piR_020326 | chr2 | − | 94,796,255 | 94,796,280 | UGGUGAAAUGAACUUCUAGGCAGCAA |

| chr8 | + | 43,498,228 | 43,498,253 | ||

| chr9 | + | 42,454,099 | 42,454,124 | ||

| chr9 | − | 43,027,769 | 43,027,794 | ||

| chr9 | − | 43,966,958 | 43,966,983 | ||

| chr9 | − | 66,114,219 | 66,114,244 | ||

| chr9 | + | 68,761,351 | 68,761,376 |

piRNA prediction found that novel_pir97924 is located on chr 8 and recognizes Long interspersed nuclear elements 1 (LINE-1). The novel_pir78110, novel_pir78107, novel_pir78097, novel_pir78094 and novel_pir76584, which are associated with the DNA/ hobo of Drosophila, Ac of maize and Tam3 of snapdragon (hAT)-Charlie transposon, are located on chromosome 3. The novel_pir73855, related to the long terminal repeat (LTR)/ Endogenous Retrovirus-K (ERVK) repetitive element, is located on chr 3. Both novel_pir70108 and novel_pir70106, which are associated with the LTR/ERVL-MaLR repetitive element, are located on chr 2. Novel_pir46604, which is related to the LTR/ERV1 repetitive element, are located on chr 18. The novel_pir33182 is located on chr 14 and is associated with the LTR/ERV1 repetitive element. The novel_pir15900 is located on chr 11 and is associated with the DNA/hAT-Tip100 repetitive element. Both novel_pir105705 and novel_pir105700 are located on the X chromosome and are associated with the LINE/L1 repetitive element (Table 2). Our results indicated that HRV16 infection-induced change of many new piRNA to recognize chromosomes.

Discussion

SncRNAs are non-protein-coding RNAs that are shorter than 50 nt. These RNAs alone or in complexes with other proteins play certain biological functions. As a type of sncRNA, piRNAs along with miRNAs and siRNAs represent the three major mechanisms of small RNA interference in most animals (Malone and Hannon 2009). piRNAs are primarily found in intergenic regions that contain large numbers of transposons and repetitive sequences, which are otherwise known as piRNA clusters (Moyano and Stefani 2015). Compared with miRNAs and siRNAs, piRNAs are longer and are not derived from double-stranded hairpin RNAs, but from single-stranded RNAs transcribed from the piRNA gene cluster near the centromere. Though piRNAs are highly diverse in sequence and variable in length, characteristics of piRNA sequences preferentially harbor a Uridine(U) at their 5′-most position (Brennecke et al. 2007; Stein et al. 2019). This 1U-bias has also been observed for other classes of small RNAs (Iwasaki et al. 2015). A report showed that there is a 60.9% bias of 1U in the sense reads for transposable elements (TEs), a 84.3% bias of 1U in antisense reads (George et al. 2015). However, in this study, we identified 28.2% bias of 1U from a total of 173,084 novel piRNAs. Whether HRV infection disturbs on the formation of 1U bias needs further study.

piRNAs have diverse biological functions, including blockage of transcription and translation, silencing of transposons, regulation of development, and modulation of the transmission of genetic information. One of the major functions of piRNA is the regulation of retrotransposons during germ cell development. Methylation is one of the most effective means of retrotransposon regulation in normal cells. However, during the early stages of germ cell and embryonic development, epigenetic reprogramming provides versatility to the development of these cells through large-scale demethylation of the genome. This, in turn, activates the transcription of a large number of retrotransposons RNAs and enhances transposition activity. piRNA is the most effective means of transposon regulation at early stage, as it ensures that the integrity and stability of the genome are maintained when the genome is passed to the offspring (Ernst et al. 2017). Recent studies using C. elegans have shown that piRNAs can regulate almost all mRNAs in germ cells. The mode of binding between piRNA and its target gene is similar to miRNA, where a low degree of mismatch is permitted. Since the binding efficiency of piRNA is dependent on its binding affinity and not richness, piRNA can still exert its functions when it is at an extremely low concentration. Besides, it was found that transgenic alteration of the recognition and matching between piRNA and its target gene resulted in continuous, stable and high expression of the unregulated target gene, which demonstrates the broadness and effectiveness of piRNA-mediated regulation of gene expression in germ cells (Shen et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2018). Furthermore, germ cell development can be severely impaired if the PIWI protein is mutated or the piRNA pathway is blocked (Watanabe et al. 2011; Gou et al. 2017). These studies demonstrate that piRNA regulates the transposition of transposons in multiple aspects and levels.

One of the major mechanisms by which piRNA inhibits the transposition of transposons is through histone modification at specific sites (Sienski et al. 2012; Le Thomas et al. 2013). A previous study showed that Piwi protein could directly interact with histone H1, which in turn increases H1 concentration at transposon gene sites and causes chromatin contraction (Watanabe and Lin 2014; Iwasaki et al. 2016). Moreover, piRNA can inhibit the transposition of LINE-1 DNA by inducing the latter's methylation (Aravin and Bourc’his 2008; Newkirk et al. 2017). In Mus musculus sperm cells, piRNA precursors transcribed from piRNA clusters bind to PIWI proteins to form piRNA-PIWI complexes. Upon entrance into the cell nucleus, recognition of the primary transcript of LINE-1 by these complexes leads to the recruitment of chromatin modifiers, which then results in the methylation of transposon-related histone H3K9 and demethylation of H3K4. The change in histone signaling subsequently recruits the DNA methyltransferase Dnmt3A/Dnmt3L complex, leading to the demethylation of LINE-1 DNA and, ultimately inhibiting LINE-1 transcription (Aravin et al. 2008). Our results showed that HRV16 infection induced the downregulation of several new piRNAs. We predicted that novel_pir97924, novel_pir105705 and novel_pir105700 could recognize LINE-1 since all of them were downregulated at the three infection time points. Therefore, we speculate that rhinovirus infection reduced these piRNAs to facilitate upregulation of LINE-1 transcription.

Our prediction also found that novel_pir78110, novel_pir78107, novel_pir78097, novel_pir78094 and novel_pir76584 are associated with the DNA/hAT-Charlie transposon. Novel_pir73855, novel_pir70108, novel_pir70106, novel_pir33182, novel_pir46604 and novel_pir15900 are related to the repetitive element LTR/ERVK, LTR/ERVL-MaLR, LTR/ERV1 and DNA/hAT-Tip100. Given that these piRNAs were downregulated, it suggests that rhinovirus infection may upregulate the expression of retrotransposons. And whether the upregulation of retrotransposons transcripts promotes pathogenesis of HRV infection or virus replication required further studies to confirm.

In addition to transposons, sufficient evidence supports the antiviral effect of piRNA pathway in host strategies for protection against invading viruses. It is worth noting that the genome analysis of Aag2 mosquito cells shows that a valuable ‘genome record’ of host virus interaction is closely related to the production of piRNAs, which leads to a genetic immune system based on piRNA (Whitfield et al. 2017). The system is believed to be a defense mechanism against viruses that have infected Anopheles aegypti in the past and is proposed to provide long-term virus specific protection for future infections. The piRNA pathway has been shown to be a contributor to antiviral immunity in mosquitoes or derived cells (Morazzani et al. 2012; Schnettler et al. 2013). The piRNA has also been found to origin from a number of mosquito-borne viruses, including Dengue virus (DENV), Chikungunya virus, Semliki Forest virus (SFV) and Rift Valley fever virus (Morazzani et al. 2012; Schnettler et al. 2013). Further, Piwi4 has been demonstrated to inhibit replication of SFV (Schnettler et al. 2013), and both Ago3 and Piwi5 benefit the generation of specific piRNAs to prohibit the proliferation of DENV and SINV in Aag2 cells (Miesen et al. 2015, 2016a, b); Recent findings showed that the human piwil 2 (hili) bound to tRNAs to inhibit HIV replication in activated CD4+ T cells (Peterlin et al. 2017). Our previous study found that Coxsackievirus B3 infection-induced changes in many piRNAs expression in HeLa cells (Yao et al. 2020). However, we don't know whether piRNAs effect on gene expression of H1-HeLa cells to benefit viral replication.

Although previous research suggests that piRNAs are germline specific, the high-throughput small RNA sequencing data show widespread presence of piRNA in multiple somatic tissues in more than 130 fruit fly, mouse and rhesus macaque, and piRNA abundance of mouse pancreas and macaque epididymis was compatible with piRNA abundance in the germline (Yan et al. 2011). These findings indicate that piRNA-like molecules might play important roles outside of the germline. The role of somatic piRNAs in cancer biology is increasingly being recognized. Growing evidence shows that piRNAs strongly correlate with tumor cell malignant phenotype and clinical stage through maintaining genomic stability (Yan et al. 2011). Not only that, some evidence showed that expression of many piRNAs are wildely found in somatic tissues of human, flies, mice and macaques (Yan et al. 2011), but also participate in cancer development (Martinez et al. 2015). Though both level of expression and the number of piRNAs are lesser in somatic cells than in germline, piRNAs contribution to tumorigenesis is significant. Research results from Martinez et al. showed that 273 known piRNAs are found in somatic tissues (n = 508), and 522 cancer-type specific piRNAs appeared in tumor samples (n = 5,752) from 12 tumor types (Gou et al. 2017). The functional role of piRNAs in nongonadal cells is a rapidly emerging field of research. Numerous piRNAs are dysregulated in tumor tissues, playing tumor-promoting or tumor-suppressor roles (Liu et al. 2019). 369 down-regulated piRNAs and 235 up-regulated piRNAs appear in 106 renal clear cell carcinoma tissues through piRNA microarray's study (Busch et al. 2015). Some invertebrates affect antiviral machinery, which piRNA pathway processes viral RNA into piRNAs (Miesen et al. 2016b). However, some virus infections, for example, CVB3, can also induce abnormal expression of piRNA in host cells (Yao et al. 2020). Our results showed that many dysregulated piRNAs appeared in HRV16-infected H1-HeLa cells again.

Most piRNA pathway proteins localize to specific cytoplasmic compartments, including nuage in animal germ cells, Yb bodies in the somatic ovarian follicle cells of flies, and the mitochondrial outer membrane in all phased piRNA-producing cells (Trenkmann 2019). The enrichment of the piRNA machinery in these subcellular structures may serve to increase the local concentration of specific proteins or protect piRNA precursors from housekeeping nucleases. Virus infection may prevent compartmentalization from entering the piRNA pathway. It is possible to explain that many piRNAs decreased in the H1-HeLa cells infected with HRV16. In the meantime, virus infection-induced increase of some piRNA through different piRNA biosynthesis mechanisms. Production of some piRNA precursor transcripts may be shunted to other sites of piRNA production (Zhang et al. 2012).

In this study, we detected and analyzed the expression of piRNAs in HRV16 infected H1-HeLa cells, and found HRV16 infection altered the expression of piRNAs compared to normal cells. Further analysis showed that rhinovirus infection could reduce some piRNAs, which may facilitate upregulation of LINE-1 transcription or upregulate retrotransposons’ expression. Though a variety of human cells, including human embryonic kidney, diploid fibroblast lines from human embryonic lung, and the HEP-2, KB, L132, and H1-HeLa cell lines, are available for growth of rhinovirus (Fields et al. 2006), only H1-HeLa cells were used to evaluate the expression of piRNAs in this study. If the expression of piRNAs from HRV16 infected different cells are compared, a comprehensive map of affected piRNA will be drawn.

Supplementary Information

Table S1 Overall Difference in piRNAs Expression between Control and HRV16-Infected H1-HeLa Cells (XLSX 8370 kb)

Table S2 Normalized piRNAs between Control and HRV16-Infected H1-HeLa Cells (XLSX 20 kb)

Table S3 Differential Expression piRNAs at Different Time Points Post Infection (XLSX 32 kb)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the China Mega-Project for Infectious Disease (2018ZX10102001, 2018ZX10711001, 2018ZX10734401 and 2018ZX10734404), and the SKLID Development Grant (2011SKLID104).

Author contributions

JH designed the experiments. JL, XW, YW, JS, QS carried out the experiments. JL, YW and JH analyzed and interpreted the data. JL, XW and JH wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Animal and Human Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Jie Li and Xinling Wang have contributed equally to this work.

Change history

7/12/2021

The subheading in Results has been updated.

Contributor Information

Yanbin Wang, Email: wangyb@cnas.org.cn.

Jun Han, Email: hanjun_sci@163.com.

References

- Aravin AA, Bourc'his D. Small RNA guides for de novo DNA methylation in mammalian germ cells. Genes Dev. 2008;22:970–975. doi: 10.1101/gad.1669408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravin A, Gaidatzis D, Pfeffer S, Lagos-Quintana M, Landgraf P, Iovino N, Morris P, Brownstein MJ, Kuramochi-Miyagawa S, Nakano T, Chien M, Russo JJ, Ju J, Sheridan R, Sander C, Zavolan M, Tuschl T. A novel class of small RNAs bind to MILI protein in mouse testes. Nature. 2006;442:203–207. doi: 10.1038/nature04916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravin AA, Sachidanandam R, Bourc'his D, Schaefer C, Pezic D, Toth KF, Bestor T, Hannon GJ. A piRNA pathway primed by individual transposons is linked to de novo DNA methylation in mice. Mol Cell. 2008;31:785–799. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke J, Aravin AA, Stark A, Dus M, Kellis M, Sachidanandam R, Hannon GJ. Discrete small RNA-generating loci as master regulators of transposon activity in Drosophila. Cell. 2007;128:1089–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch J, Ralla B, Jung M, Wotschofsky Z, Trujillo-Arribas E, Schwabe P, Kilic E, Fendler A, Jung K. Piwi-interacting RNAs as novel prognostic markers in clear cell renal cell carcinomas. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2015;34:61. doi: 10.1186/s13046-015-0180-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J, Guo JM, Xiao BX, Miao Y, Jiang Z, Zhou H, Li QN. piRNA, the new non-coding RNA, is aberrantly expressed in human cancer cells. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412:1621–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J, Deng H, Xiao B, Zhou H, Zhou F, Shen Z, Guo J. piR-823, a novel non-coding small RNA, demonstrates in vitro and in vivo tumor suppressive activity in human gastric cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2012;315:12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L, Lou Y, Zhang X, Zhou H, Deng H, Song H, Yu X, Xiao B, Wang W, Guo J. Detection of circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood from patients with gastric cancer using piRNAs as markers. Clin Biochem. 2011;44:1050–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkema JS, van Ewijk BE, Wilbrink B, Wolfs TFW, Kimpen JLL, van der Ent CK. Frequency and duration of rhinovirus infections in children with cystic fibrosis and healthy controls. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35:379–383. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst C, Odom DT, Kutter C. The emergence of piRNAs against transposon invasion to preserve mammalian genome integrity. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1411. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01049-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM (2006) Fields Virology. 5th Edition. 2:3177

- George P, Jensen S, Pogorelcnik R, Lee J, Xing Y, Brasset E, Vaury C, Sharakhov IV. Increased production of piRNAs from euchromatic clusters and genes in Anopheles gambiae compared with Drosophila melanogaster. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2015;8:50. doi: 10.1186/s13072-015-0041-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard A, Sachidanandam R, Hannon GJ, Carmell MA. A germline-specific class of small RNAs binds mammalian Piwi proteins. Nature. 2006;442:199–202. doi: 10.1038/nature04917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou LT, Dai P, Yang JH, Xue Y, Hu YP, Zhou Y, Kang JY, Wang X, Li H, Hua MM, Zhao S, Hu SD, Wu LG, Shi HJ, Li Y, Fu XD, Qu LH, Wang ED, Liu MF. Pachytene piRNAs instruct massive mRNA elimination during late spermiogenesis. Cell Res. 2015;25:266. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou LT, Kang JY, Dai P, Wang X, Li F, Zhao S, Zhang M, Hua MM, Lu Y, Zhu Y, Li Z, Chen H, Wu LG, Li D, Fu XD, Li J, Shi HJ, Liu MF. Ubiquitination-deficient mutations in human piwi cause male infertility by impairing histone-to-protamine exchange during spermiogenesis. Cell. 2017;169(1090–1104):e1013. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunawardana N, Finney L, Johnston SL, Mallia P. Experimental rhinovirus infection in COPD: implications for antiviral therapies. Antivir Res. 2014;102:95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hombach S, Kretz M. Non-coding RNAs: classification, biology and functioning. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;937:3–17. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-42059-2_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang XA, Yin H, Sweeney S, Raha D, Snyder M, Lin H. A major epigenetic programming mechanism guided by piRNAs. Dev Cell. 2013;24:502–516. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki YW, Siomi MC, Siomi H. PIWI-Interacting RNA: its biogenesis and functions. Ann Rev Biochem. 2015;84:405–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki YW, Murano K, Ishizu H, Shibuya A, Iyoda Y, Siomi MC, Siomi H, Saito K. Piwi modulates chromatin accessibility by regulating multiple factors including histone H1 to repress transposons. Mol Cell. 2016;63:408–419. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirino Y, Mourelatos Z. Mouse Piwi-interacting RNAs are 2'-O-methylated at their 3' termini. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:347–348. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku HY, Lin H. PIWI proteins and their interactors in piRNA biogenesis, germline development and gene expression. Natl Sci Rev. 2014;1:205–218. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwu014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramochi-Miyagawa S, Watanabe T, Gotoh K, Totoki Y, Toyoda A, Ikawa M, Asada N, Kojima K, Yamaguchi Y, Ijiri TW, Hata K, Li E, Matsuda Y, Kimura T, Okabe M, Sakaki Y, Sasaki H, Nakano T. DNA methylation of retrotransposon genes is regulated by Piwi family members MILI and MIWI2 in murine fetal testes. Genes Dev. 2008;22:908–917. doi: 10.1101/gad.1640708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Thomas A, Rogers AK, Webster A, Marinov GK, Liao SE, Perkins EM, Hur JK, Aravin AA, Toth KF. Piwi induces piRNA-guided transcriptional silencing and establishment of a repressive chromatin state. Genes Dev. 2013;27:390–399. doi: 10.1101/gad.209841.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggewie M, Schnettler E. RNAi-mediated antiviral immunity in insects and their possible application. Curr Opin Virol. 2018;32:108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Hong J, Hong M, Wang Y, Yu T, Zang S, Wu Q. piRNA-823 delivered by multiple myeloma-derived extracellular vesicles promoted tumorigenesis through re-educating endothelial cells in the tumor environment. Oncogene. 2019;38:5227–5238. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-0788-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipovich L, Johnson R, Lin CY. MacroRNA underdogs in a microRNA world: evolutionary, regulatory, and biomedical significance of mammalian long non-protein-coding RNA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799:597–615. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Dou M, Song X, Dong Y, Liu S, Liu H, Tao J, Li W, Yin X, Xu W. The emerging role of the piRNA/piwi complex in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:123. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1052-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makris S, Johnston S. Recent advances in understanding rhinovirus immunity. F1000Research. 2018;7:1537. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.15337.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone CD, Hannon GJ. Small RNAs as guardians of the genome. Cell. 2009;136:656–668. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez VD, Vucic EA, Thu KL, Hubaux R, Enfield KS, Pikor LA, Becker-Santos DD, Brown CJ, Lam S, Lam WL. Unique somatic and malignant expression patterns implicate PIWI-interacting RNAs in cancer-type specific biology. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10423. doi: 10.1038/srep10423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miesen P, Girardi E, van Rij RP. Distinct sets of PIWI proteins produce arbovirus and transposon-derived piRNAs in Aedes aegypti mosquito cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:6545–6556. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miesen P, Ivens A, Buck AH, van Rij RP. Small RNA profiling in dengue virus 2-infected aedes mosquito cells reveals viral piRNAs and novel host miRNAs. PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miesen P, Joosten J, van Rij RP. PIWIs Go Viral: Arbovirus-Derived piRNAs in Vector Mosquitoes. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1006017. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EK, Linder J, Kraft D, Johnson M, Lu PC, Saville BR, Williams JV, Griffin MR, Talbot HK. Hospitalizations and outpatient visits for rhinovirus-associated acute respiratory illness in adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:734. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morazzani EM, Wiley MR, Murreddu MG, Adelman ZN, Myles KM. Production of virus-derived ping-pong-dependent piRNA-like small RNAs in the mosquito soma. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002470. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyano M, Stefani G. piRNA involvement in genome stability and human cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2015;8:38. doi: 10.1186/s13045-015-0133-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newkirk SJ, Lee S, Grandi FC, Gaysinskaya V, Rosser JM, Vanden Berg N, Hogarth CA, Marchetto MCN, Muotri AR, Griswold MD, Ye P, Bortvin A, Gage FH, Boeke JD, An W. Intact piRNA pathway prevents L1 mobilization in male meiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:E5635–E5644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1701069114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterlin BM, Liu P, Wang X, Cary D, Shao W, Leoz M, Hong T, Pan T, Fujinaga K. Hili inhibits HIV replication in activated T cells. J Virol. 2017;91:e00237-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00237-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouget C, Papin C, Boureux A, Meunier AC, Franco B, Robine N, Lai EC, Pelisson A, Simonelig M. Maternal mRNA deadenylation and decay by the piRNA pathway in the early drosophila embryo. Nature. 2010;467:1128–1132. doi: 10.1038/nature09465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar A, Volff JN, Vaury C. piRNAs and their diverse roles: a transposable element-driven tactic for gene regulation? Faseb j. 2017;31:436–446. doi: 10.1096/fj.201600637RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnettler E, Donald CL, Human S, Watson M, Siu RW, McFarlane M, Fazakerley JK, Kohl A, Fragkoudis R. Knockdown of piRNA pathway proteins results in enhanced Semliki Forest virus production in mosquito cells. J Gen Virol. 2013;94:1680–1689. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.053850-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen EZ, Chen H, Ozturk AR, Tu S, Shirayama M, Tang W, Ding YH, Dai SY, Weng Z, Mello CC. Identification of piRNA binding sites reveals the argonaute regulatory landscape of the C. elegans Germline. Cell. 2018;172(937–951):e918. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sienski G, Donertas D, Brennecke J. Transcriptional silencing of transposons by Piwi and maelstrom and its impact on chromatin state and gene expression. Cell. 2012;151:964–980. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siomi MC, Sato K, Pezic D, Aravin AA. PIWI-interacting small RNAs: the vanguard of genome defence. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:246–258. doi: 10.1038/nrm3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein CB, Genzor P, Mitra S, Elchert AR, Ipsaro JJ, Benner L, Sobti S, Su YJ, Hammell M, Joshua-Tor L, Haase AD. Decoding the 5' nucleotide bias of PIWI-interacting RNAs. Nat Commun. 2019;10:828. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08803-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenberg-Hammar K, Hedlin G, Soderhall C. Rhinovirus and preschool wheeze. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2017;28:513–520. doi: 10.1111/pai.12740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trenkmann M. Synthetic readers and writers for mammalian chromatin. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20:68–69. doi: 10.1038/s41576-018-0090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Liang C, Liu J, Xiao H, Huang S, Xu J, Li F. Prediction of piRNAs using transposon interaction and a support vector machine. BMC Bioinform. 2014;15:419. doi: 10.1186/s12859-014-0419-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Lin H. Posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression by Piwi proteins and piRNAs. Mol Cell. 2014;56:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Tomizawa S, Mitsuya K, Totoki Y, Yamamoto Y, Kuramochi-Miyagawa S, Iida N, Hoki Y, Murphy PJ, Toyoda A, Gotoh K, Hiura H, Arima T, Fujiyama A, Sado T, Shibata T, Nakano T, Lin H, Ichiyanagi K, Soloway PD, Sasaki H. Role for piRNAs and noncoding RNA in de novo DNA methylation of the imprinted mouse Rasgrf1 locus. Science. 2011;332:848–852. doi: 10.1126/science.1203919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield ZJ, Dolan PT, Kunitomi M, Tassetto M, Seetin MG, Oh S, Heiner C, Paxinos E, Andino R. The diversity, structure, and function of heritable adaptive immunity sequences in the aedes Aegypti genome. Curr Biol. 2017;27(3511):3519.e3517. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z, Hu HY, Jiang X, Maierhofer V, Neb E, He L, Hu Y, Hu H, Li N, Chen W, Khaitovich P. Widespread expression of piRNA-like molecules in somatic tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:6596–6607. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H, Wu QL, Sun CY, Ai LS, Deng J, Zhang L, Chen L, Chu ZB, Tang B, Wang K, Wu XF, Xu J, Hu Y. piRNA-823 contributes to tumorigenesis by regulating de novo DNA methylation and angiogenesis in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2015;29:196–206. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H, Wang X, Song J, Wang Y, Song Q, Han J. Coxsackievirus B3 infection induces changes in the expression of numerous piRNAs. Arch Virol. 2020;165:105–114. doi: 10.1007/s00705-019-04451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Wang J, Xu J, Zhang Z, Koppetsch BS, Schultz N, Vreven T, Meignin C, Davis I, Zamore PD, Weng Z, Theurkauf WE. UAP56 couples piRNA clusters to the perinuclear transposon silencing machinery. Cell. 2012;151:871–884. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Tu S, Stubna M, Wu WS, Huang WC, Weng Z, Lee HC. The piRNA targeting rules and the resistance to piRNA silencing in endogenous genes. Science. 2018;359:587–592. doi: 10.1126/science.aao2840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Overall Difference in piRNAs Expression between Control and HRV16-Infected H1-HeLa Cells (XLSX 8370 kb)

Table S2 Normalized piRNAs between Control and HRV16-Infected H1-HeLa Cells (XLSX 20 kb)

Table S3 Differential Expression piRNAs at Different Time Points Post Infection (XLSX 32 kb)