Abstract

In recent years, the number of dental technicians (DTs) in Japan has fluctuated around 35,000. However, this number is expected to decline dramatically in future, given the increase in the number of older DTs and marked decline in the number of younger DTs. This is a review of various reports analyzing the supply of and demand for DTs in Japan and a description of prospective measures to ensure a sufficient supply of DTs in future.

Several previous reports have suggested that the number of DTs will fall more rapidly than the demand. However, there are only few quantitative assessments of the supply of and demand for DTs, and extensive investigation of how the decrease in numbers will affect the future of dental services is required.

The role of each Japanese dental profession, that is, dentists, dental hygienists, and dental technicians, is well-defined; they are to provide dental services to the Japanese people. Therefore, it is necessary to maintain the required number of each dental profession in future. For clarity on the social situation of DTs and to help in taking immediate measures, it is important to analyze the supply and demand of DTs from various perspectives, such as region.

Keywords: Dental technician, Supply and demand, Future estimation, Report on Public Health Administration and Services

1. Introduction

The number of dental technicians (DTs) working in Japan has fluctuated around 35,000 in recent years [1]. However, the number of older DTs is increasing, while that of younger DTs is decreasing [1]. Hence, the number of DTs in Japan may decrease dramatically in future [2]. In addition, many schools training DTs have closed or are unable to meet their enrollment capacities, which may further accelerate the decline. On the other hand, given the improved oral health of the Japanese people [3,4] and increasing availability of dental technologies such as computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM) systems [5], some authors argue that it is only natural for the number of DTs to decline.

In reports by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) of Japan, indicators of “supply” and “demand” related to healthcare professionals are defined and estimated, to quantitatively assess the actual situation of healthcare professionals [[6], [7], [8]]. Regarding the analysis of their supply, trend analyses and estimations of the prospective number of healthcare professionals are performed [[6], [7], [8]]. On the other hand, the demand for healthcare professionals is analyzed considering the number of diseases and number of patients as indicators [[6], [7], [8]]. Since the duties of DTs are to manufacture prosthetic restorations, the total number of prosthetic restorations manufactured in Japan is an appropriate indicator of the demand for DTs. However, there are few reports on the social conditions of DTs in relation to their supply and demand; therefore, this article is a detailed analysis of the supply and demand of DTs. Based on a quantitative assessment of the social conditions of DTs and an understanding of their issues, policymakers need to make appropriate policies to maintain DTs.

This article aimed to summarize the current status of the Japanese DT system and DT employment, review the literature on the analysis of DT supply and demand, and propose prospective measures to ensure a sufficient supply of DTs in future.

2. Summary of the dental technician system and employment in Japan

The Japanese DT system started with the Dental Technicians Act in 1955. Persons wishing to become DTs must enroll in a DT school. As of March 2020, there were 49 of such schools in Japan, including universities, colleges, and vocational schools [9,10]. According to the law, the training for DTs should be at least two years. Thereafter, graduates of such programs are required to take the Japanese National Examination for Dental Technicians. This exam is divided into a theory section (consists of: dental materials science, dental anatomy, stomatognathic function science, dental technology for removable dentures, dental technology for fixed dental prostheses and restorations, dental technology for orthodontic appliances, dental technology for pedodontics appliances, and laws and regulations for dental technicians) and practical section. Successful candidates submit their application documents to the MHLW for registration in the DT directory, after which they receive their DT license.

The scope of practice of DTs as specified by the Dental Technicians Act entails the manufacturing, repair and alteration of prostheses, restorations, and orthodontic appliances. DTs are prohibited from undertaking activities that require direct contact with the patient’s oral cavity, such as dental impression taking, maxillomandibular registration, trial fitting, and restoration fitting.

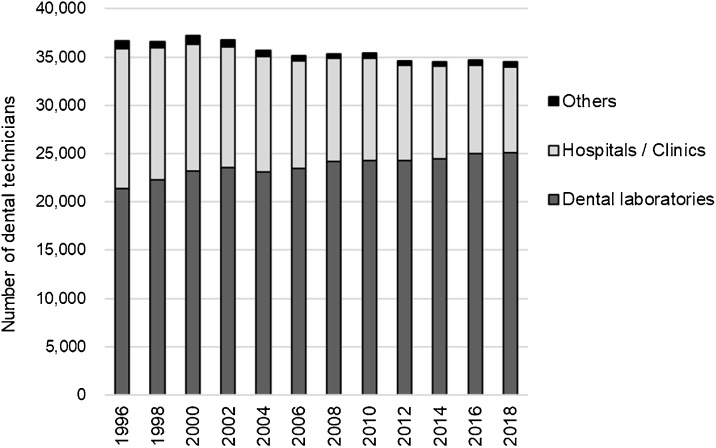

The law requires that practicing DTs should submit a notice of working status every two years (on even years on the Gregorian calendar) to the prefectural governor. The data is published in the MHLW Report on Public Health Administration and Services [1]. A 2018 study showed that 34,468 DTs (28.7% of the total 120,157 people with DT licenses) were actively working [1]. According to this study, most of the DTs worked in dental laboratories (72.7%), followed by hospitals and clinics (25.7%), education and training institutions (0.8%), and other settings (0.8%). Recent trends show a decreasing number of DTs working in hospitals and clinics and an increasing number in dental laboratories (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Yearly trend of number of dental technicians by working place.

As of 2018, there were 68,613 dental clinics [11] and 21,004 dental laboratories in Japan [1]. A total of 91.7% of Japanese dental clinics ordered prosthetic restorations to be manufactured in external dental laboratories [11]. Most dental laboratories operated independently, and 76.7% of dental laboratories had only one worker. Dental laboratories that had 2, 3, 4, 5–9, 10–19, and >20 workers comprised 12.4%, 4.2%, 2.2%, 3.2%, 0.8%, and 0.5% of the total number of dental laboratories, respectively [1].

3. Analysis of DT supply and other analyses

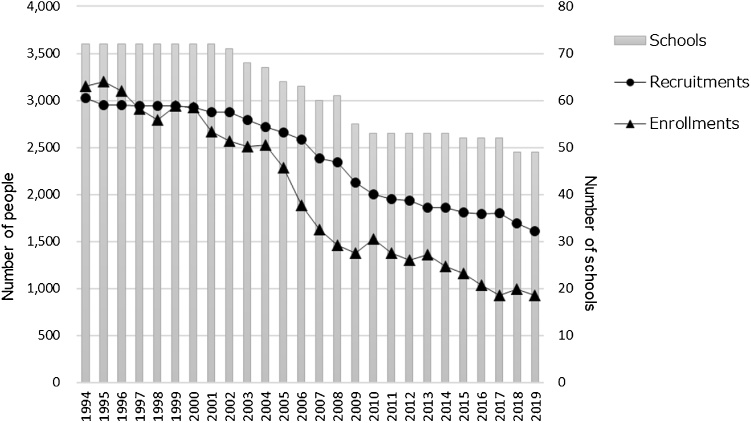

The number of students enrolling in DTs schools has decreased; this has resulted in the closure of several of these schools in the last 20 years. Although there were 72 DT schools nationwide in 2000, 49 were recorded in 2019 (Fig. 2) [9,10]. Consequently, the number of DTs who qualify each year has been steadily falling, as shown by the following numbers: 1104 in 2016, 987 in 2017, 902 in 2018, 798 in 2019, and 838 in 2020 [12]. Moreover, regarding the age of DTs, as of 2018, 10.8% were in their 20 s, 16.1% in their 30 s, 23.1% in their 40 s, and 50.0% in their 50 s and above; therefore, the young DTs constituted the minority [1]. Therefore, there is a concern that the number of DTs will decrease in future [2].

Fig. 2.

Yearly trend of number of dental technician schools and recruitments/enrollments.

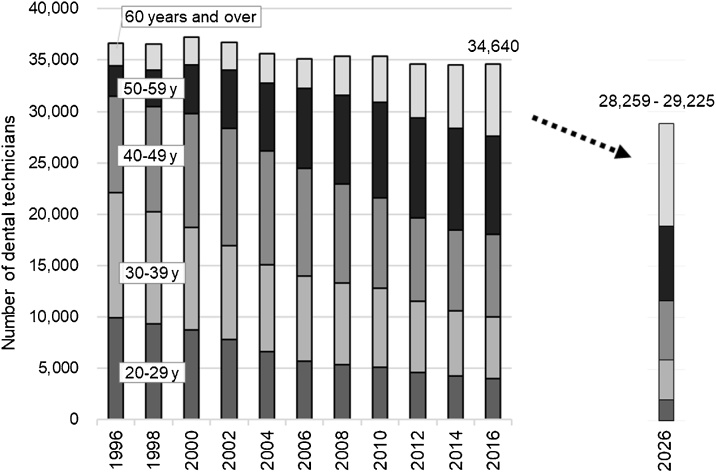

To find countermeasures for this situation, Oshima et al. estimated the prospective number of DTs who will be working in Japan [13]. Based on the analysis of data from the Report on Public Health Administration and Services and the numbers of those who passed the DT national examination, using the cohort change rate method, the number of practicing DTs is projected to decrease to 28,259–29,225 by 2026, that is, a decrease of approximately 5400–6400 from 2016 [13] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Actual and projected the number of dental technicians.

In addition, to obtain supplementary data of the supply of DTs, surveys were conducted to understand the actual situation of DTs in specific regions and the awareness of DTs among high school students.

A survey on dental clinics in Akita region reported that about 50% of clinics were observing signs of decline in DT numbers, such as dental laboratories with no successor [14]. After confirming the addresses of dental laboratories that supplied prosthetic restorations to dental clinics in this region, 84.2% of these clinics ordered them from dental laboratories in the same prefecture. This suggests that if the number of DTs declines further, it may be difficult to find a dental laboratory in Akita to order prosthetic restorations from. Moreover, a survey on high schoolers on their knowledge of health-care related occupations showed that about half of high schoolers had never heard of DT as an occupation, while only 10% were unfamiliar with dental hygienists [15]. These differences will inevitably affect the likelihood of high schoolers choosing the DT profession as a career.

The aforementioned reports show that many issues affect DT supply, and also support the assertion that DT numbers may decrease greatly in future.

4. Relationship between the demand for prostheses and DT supply

In discussing DT demand, it is helpful to understand data that reflects changes and trends in the manufacturing of prosthetic restorations. Japan has a universal healthcare insurance system, and some of the prosthetic restorations are covered by the medical insurance system and are set as official prices. Data on prosthetic restorations covered by the medical insurance system are aggregated by the MHLW [5,16]. A secondary analysis of these data will help visualize the trend of the number of prosthetic restorations manufactured nationwide (in Japan).

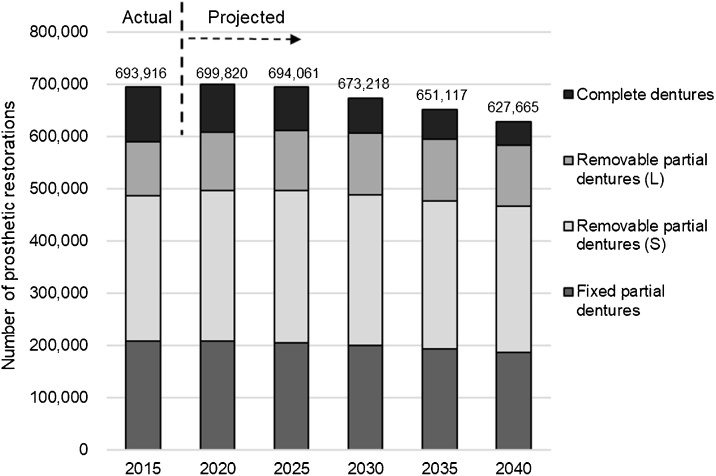

A report of data from the Statistics of Medical Care Activities in Public Health Insurance showed that the number of new complete dentures has decreased slightly, but numbers of fixed partial dentures and removable partial dentures have remained constant [5,17]. This may be because the demand for complete dentures has shifted to removable partial dentures and fixed partial dentures, due to the increase in the number of remaining teeth in the elderly [3] and the increase in the proportion of elderly people [18]. The numbers of these prosthetic restorations for missing teeth are projected to remain constant until 2025, but may start to fall gradually around 2030 (Fig. 4) [19].

Fig. 4.

Actual and projected number of dentures manufactured.

Partial dentures (S): The number of missing teeth per denture is 1–8, Partial dentures (L): The number of missing teeth per denture is 9–14.

In addition, reports using other MHLW statistical data can provide information on trends in dental prosthetic treatment. In the Patient Survey, the estimated numbers of patients in dental clinics were expressed as provided treatments by disease or injury type [20]. Of these, the numbers of dental prosthetic treatment were unchanged. When the data was stratified by age group, treatment numbers increased gradually for patients ≥65 years. An analysis of the Survey of Dental Diseases suggested that the number of people using prostheses does not decrease with an increase in the number of remaining teeth [3,21].

It is important to assess whether these trends in population demographics will continue. A report on the projected population by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research showed that although the Japanese population has been decreasing since 2010, the number of people aged ≥65 years is expected to keep rising until 2040, after which it is expected to start declining [18].

The reports collectively suggest that while the demand for the manufacturing of prosthetic restorations and dental prosthetic treatment will remain steady for some time, it is expected to decrease in the long run, especially considering the changes in the population structure. Therefore, based on the review of the previous reports, supply of and demand for DTs will decrease thereafter, but the drop in the number of DTs will occur faster.

5. Limitations of the DT supply and demand analyses

Although the previous section provided an overview of some analyses of the supply and demand of DTs, these analyses had several limitations. First, the authors calculated future estimates for prosthetic restorations for missing teeth such as complete dentures, removable partial dentures, and fixed partial dentures under the Japanese medical insurance system [5,16], but did not calculate future estimates for prosthetic restorations other than prosthetic restorations for missing teeth. This creates the need for a further detailed analysis of the number of different types of prosthetic restorations using statistical data, such as data from the Statistics of Medical Care Activities in Public Health Insurance [5] and the National Database of Health Insurance Claims and Specific Health Checkups of Japan [16]. Second, the Japanese medical insurance system does not cover all types of prosthetic restorations, such as metal base dentures and porcelain fused to metal crowns. Therefore, the analyses considered only prosthetic restorations that are covered by the medical insurance system to evaluate the demand for DTs. Third, there are no reports on the analysis of the job description of DTs such as dentures, crown restoration, CAD/CAM, etc. This is unlike the analysis of the supply and demand of medical doctors that was divided into detailed parameters, such as hospitalization, outpatient care, and long-term care welfare [6]. Therefore, studies that classify the DTs work in detail are required, for improved data accuracy.

Although nationwide data e.g., government statistics are the ideal in analyzing the supply and demand of healthcare professionals, available DT-related nationwide data is scarce. Therefore, other sources of data for measuring the state of DTs in a specific area, such as the Akita survey, were used [14].

6. Measures to prevent a shortage of DTs

The MHLW has established the Commission for Recruitment and Training of Dental Technicians to invite experts to discuss measures related to education, training, and recruitment of DTs [9]. This commission held eight meetings between May 2018 and December 2019. The topics that were discussed in these meetings are summarized briefly below.

Consideration was given to revising the DT scope of practice to promote further cooperation between dentists and DTs. Unlike DTs in some countries [22], the Japanese system prohibits DTs from undertaking activities that involve direct contact with the patient’s oral cavity. In addition, most contemporary DTs work in dental laboratories, which are not conducive for interaction with patients. However, there are many cases in which dental prosthetic treatment would proceed more efficiently through increased dentist-DT collaboration. The benefits of this teamwork are not limited to the dental examination room, but extend to home-visit dental treatment as well [23]. Most home-visit dental treatment patients use prostheses [24], and the DT can assist the dentist during the prosthetic treatment in such visits—this may shorten the consultation times [23]. Therefore, it is necessary to consider reviewing the scope of work of DTs, including work that involves direct contact with the patient's oral cavity. If it is revised, the educational content of the DT training will also need to be changed.

Consideration was also given to promoting the efficiency of DTs by improving their working environment. Recently, the use of the CAD system has become widespread among DTs [25,26]. Since CAD requires work on a computer, it is possible to implement teleworking; however, the current Japanese system does not allow the operation of CAD by telework. The number of women among the younger DTs is increasing [1]. Female dental healthcare professionals have a higher turnover rate than male professionals due to life events, such as childbirth [27,28]. Allowing teleworkers to operate CAD is expected to provide a more comfortable working environment for women.

Consideration was also given to strategies to promote public awareness of dental services and dental technology. A recent survey of parents with high school-aged children showed that 25.5% of parents had an interest in their child pursuing a career as a dentist, 18.8% in their child in becoming a dental hygienist, and 15.5% in DT as a future occupation for their child [29]. The remarkable characteristic of parents who were interested in DT as a future career for their child was that they had friends or acquaintances who were DTs. This finding shows that parents who have DT acquaintances are more likely to understand the job responsibilities of DTs, and thus are interested in it as a future profession for their child. Thus, raising awareness on the occupational details of DTs could lead to a higher level of recruitment of dental professionals.

The environment surrounding dentists and DTs has changed dramatically since 1955 when the Dental Technicians Act was enacted. The DT system must adapt accordingly. The discussions of the MHLW commission [9] shed light on the challenges faced by DTs, and an early implementation of measures to respond to them is anticipated by DTs and other dental professionals.

7. Conclusions

This manuscript sought to provide an overview of the various reports that have analyzed the supply of and demand for DTs in Japan, and the key points of suggested policies to ensure adequate DT recruitment. In summary, previous studies point to the concern that DT numbers will decrease at a faster rate than the demand for prosthetic restorations, which may lead to a shortage of DTs. However, reports that have quantitatively assessed the supply of and demand for DTs are few, and the effects of the decline in DT numbers on the future of dental services are poorly defined.

The role of each Japanese dental profession, that is, dentists, dental hygienists, and dental technicians, is well-defined; they are to provide dental services to the Japanese people. Therefore, it is necessary to maintain the required number of each dental profession in future. For clarity on the social situation of DTs and to help in taking immediate measures, it is important to analyze the supply and demand of DTs from various perspectives, such as region.

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest are declared in relation to this manuscript.

Role of the funding source

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP19K10435.

References

- 1.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Report on Public Health Administration and Services. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/36-19.html. (in Japanese) [Accessed 6 April 2020].

- 2.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Commission on the Improvement of the Qualifications of Dentists: Interim Report. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/shingi2/0000189587.html. (in Japanese) [Accessed 1 April 2020].

- 3.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Survey of Dental Diseases. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/62-17.html. (in Japanese) [Accessed 9 April 2020].

- 4.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. National Health and Nutrition Survey. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkou/kenkou_eiyou_chousa.html. (in Japanese) [Accessed 6 April 2020].

- 5.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Statistics of Medical Care Activities in Public Health Insurance. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/26-19.html. (in Japanese) [Accessed 8 April 2020].

- 6.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Commission on the Supply and Demand of Medical professionals, subcommittee of Physician: Third Interim Report. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/shingi2/0000209695.html. (in Japanese) [Accessed 20 March 2020].

- 7.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Commission on the Supply and Demand of Medical professionals, subcommittee of Nurses: Interim Report. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/newpage_07927.html. (in Japanese) [Accessed 20 March 2020].

- 8.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Commission on the Supply and Demand of Medical professionals, subcommittee of Physical therapists and Occupational therapists. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/shingi2/0000132674_00001.html. (in Japanese) [Accessed 20 March 2020].

- 9.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Commission for Recruitment and Training of Dental Technicians. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/shingi/other-isei_547700.html. (in Japanese) [Accessed 8 April 2020].

- 10.Japan Society for Education of Dental Technology. http://www.jsedt.jp/. [Accessed 1 April 2020].

- 11.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Survey of Medical Institutions. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/79-1.html. (in Japanese) [Accessed 6 April 2020].

- 12.Japan Foundation of Dental Promotion. http://www.dc-training.or.jp/siken2.html. [Accessed 6 April 2020].

- 13.Oshima K., Takei R., Ando Y. An estimation of the number of future dental technicians. Jpn J Dent Prac Admin. 2019;54:199–207. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oshima K., Ando Y., Suzuki F., Fujiwara M. Understanding of status of dental techniques and situation of sign regarding decreasing number of dental technicians at dental clinics: an analysis through a questionnaire survey with members of Akita Dental Association. Jpn J Dent Prac Admin. 2018;53:64–71. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oshima K., Ando Y. Study on awareness of healthcare professionals including dental hygienists and dental technicians using a web-based survey: approximately half of high school students unaware of the occupation of dental technician. Jpn J Dent Prac Admin. 2018;52:200–210. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. National Database of Health Insurance Claims and Specific Health Checkups of Japan. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000177182.html. (in Japanese) [Accessed 6 April 2020].

- 17.Oshima K., Ando Y., Aoyama H. Change in the number of denture according to survey/statistics of medical care activities in public health insurance. Health Sci Health Care. 2016;16:48–54. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Institute of Population and Security Research. Population Projections for Japan. http://www.ipss.go.jp/index-e.asp. [Accessed 8 April 2020].

- 19.MHLW grants system. Study on the promotion of reinstatement support for dental hygienists and dental technicians: Analysis of supply and demand for dental technicians. https://mhlw-grants.niph.go.jp/project/26170/1. (in Japanese) [Accessed 2 April 2020].

- 20.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Patient Survey. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/10-20.html. (in Japanese) [Accessed 8 April 2020].

- 21.Sato Y., Issiki Y. Estimation of denture patients’ absolute number in elderly from survey of dental diseases and vital statistics. Jpn J Dent Prac Admin. 2014;49:162–167. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 22.International Federation of Denturists. https://international-denturists.org/index.php/en/. [Accessed 8 April 2020].

- 23.Kamijo S., Sugimoto K., Oki M., Tsuchida Y., Suzuki T. Trends in domiciliary dental care including the need for oral appliances and dental technicians in Japan. J Oral Sci. 2018;60:626–633. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.18-0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oshima K., Miura H. Characteristics of dental clinics providing home-visit dental treatment based on oral health management: focusing on the use of dental hygienists. Jpn J Dent Prac Admin. 2018;53:166–173. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Japan Dental Technologists Association. Survey of dental technicians. http://sp.nichigi.or.jp/about_shikagikoshi/2018jittaichousa_gaiyou.html. [Accessed 10 April 2020].

- 26.Miyazaki T., Hotta Y., Kunii J., Kuriyama S., Tamaki Y. A review of dental CAD/CAM: current status and future perspectives from 20 years of experience. Dent Mater J. 2009;28:44–56. doi: 10.4012/dmj.28.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newton J.T., Buck D., Gibbons D.E. Workforce planning in dentistry: the impact of shorter and more varied career patterns. Community Dent Health. 2001;18:236–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ayers K.M., Thomson W.M., Rich A.M., Newton J.T. Gender differences in dentists’ working practices and job satisfaction. J Dent. 2008;36:343–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oshima K., Ando Y. Periodic dental visits give parents interest in their child becoming a dentist/dental hygienist as a future profession. Jpn J Dent Prac Admin. 2019;54:48–57. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]