Abstract

The treatment of malignant bone tumors by chemotherapeutics often receives poor therapeutic response due to the specific physiological bone environment, and thus calls for the development of new therapeutic options. Here, we reported a bone-targeted protein nanomedicine for this purpose. Saporin, a toxin protein, was co-assembled with a boronated polymer for intracellular protein delivery, and the formed nanoparticles were further coated with an anionic polymer poly (aspartic acid) to shield the positive charges on nanoparticles and provide the bone targeting function. The prepared ternary complex nanoparticles showed high bone accumulation both in vitro and in vivo, and could reverse the surface charge property from negative to positive after locating at tumor site triggered by tumor extracellular acidity. The boronated polymer in the de-shielded nanoparticles further promote intracellular delivery of saporin into tumor cells, exerting the anticancer activity of saporin by inactivation of ribosomes. As a result, the bone-targeted and saporin-loaded nanomedicine could kill cancer cells at a low saporin dose, and efficiently prevented the progression of osteosarcoma xenograft tumors and bone metastatic breast cancer in vivo. This study provides a facile and promising strategy to develop protein-based nanomedicines for the treatment of malignant bone tumors.

Keywords: Boronated polymer, Dendrimers, Intracellular protein delivery, Bone targeting, Cancer therapy

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

This work developed a targeted and protein-based nanotherapeutics for the treatment of bone tumors.

-

•

The nanomedicine showed tumor acitivity activated charge reveral property.

-

•

The protein nanotherapeutics efficiently inhibited the growth of bone tumors and osteolysis in vivo.

1. Introduction

Malignant bone tumors are classified into orthotopic bone tumors and bone metastatic tumors. Osteosarcoma, the most common type of orthotopic bone tumor, mainly occurs in adolescents and young adults. Though the five-year survival rate for patients with localized osteosarcoma has been improved to 60–80%, the rate for the ones with metastatic osteosarcoma is still low (15–30%) [1]. Bone metastasis is frequently diagnosed in advanced cancer patients such as breast and prostate cancers. Nearly 73% breast cancers and 68% prostate cancers may progress to bone metastasis [2]. Bone metastasis is life threatening and will cause serious complications such as pathological fracture, bone pain, neurological deficit and paralysis, severely affecting the quality of life. The current scenarios for the treatment of orthotopic and metastatic bone cancers are far from satisfactory. Patients with surgical resection of bone tumor usually suffer from reoccurrence due to incomplete removal of tumor located in bone marrows. In addition, surgical treatment is not available for patients with multiple metastatic bone tumors. Most bone tumors are not sensitive to conventional radiotherapy due to the specific physiological bone environment. The treatment of bone tumors by chemotherapeutics is also limited due to multidrug resistance and poor drug accumulation at the bone tumor site.

In recent years, bone-targeted nanomedicines with enhanced drug accumulation at bone tissues were proposed as promising candidates for the treatment of bone tumors [3]. Inorganic minerals in bone tissues such as hydroxyapatite were proposed as the targets. Ligands with high hydroxyapatite binding affinities such as bisphosphonates, aspartic acid-rich peptides, phytic acid, anionic polymers and tetracycline were conjugated to nanoparticles to improve their bone accumulation [4]. These ligands possess stronger binding with highly crystallized hydroxyapatite, and thus are beneficial for targeted delivery of therapeutic agents to bone defects and osteolytic lesions around bone tumors. For example, bisphosphonate conjugated poly (lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) or poly (lactic acid) (PLA) nanoparticles were loaded with anticancer drugs for the treatment of metastatic bone tumors and osteosarcoma [5]. The natural compound phytic acid with six phosphonate groups were reacted with cisplatin to prepare bone-targeted nanomedicine for the treatment of bone metastatic cancer [6]. Bisphosphonate and peptide conjugated nanoparticles were also proposed to treat bone tumors via photothermal therapy [7]. Besides, targeted nanoparticle mediated combination therapies were proposed to enhance therapeutic response in bone tumor therapy [8], and to break down the vicious cycle between tumor growth and bone resorption [9]. Though these nanomedicines showed promising therapeutic results in vivo, there is still an urgent need to develop novel and efficient therapeutic scenarios for the treatment of orthotopic bone tumors and metastatic ones.

Protein drugs have high potency and specificity compared to conventional small-molecule chemotherapeutics [10]. However, proteins are easily degraded by proteases and hard to penetrate through cell membranes to act on intracellular targets. To solve these issues, polymers that are capable of protecting protein against proteolysis and delivering protein cargoes inside cells were developed [11]. Boronated polymer was proposed to complex with proteins via a combination of nitrogen-boronate coordination and ionic interactions, and showed promising efficiency in cytosolic delivery of cargo proteins and peptides with maintained bioactivity [12]. Here, we used a boronated dendrimer as the protein carrier to deliver saporin, a toxin protein into bone tumor cells for cancer therapy (Fig. 1). The polymer/saporin nanoparticle was further coated with a bone targeting polymer poly-(α, β)-DL-aspartic acid (PASP, pKa4.9) via ionic interactions. Besides bone targeting, PASP coating could turn the charge property of the nanoparticles from positive to negative, which avoids the rapid clearance of cationic nanoparticles by reticuloendothelial system during blood circulation. The de-shielding of PASP coating could be triggered by protonation of PASP when the nanoparticles were located in tumor microenvironment, and saporin was further delivered into tumor cells by the boronated polymer to exert its anticancer activity.

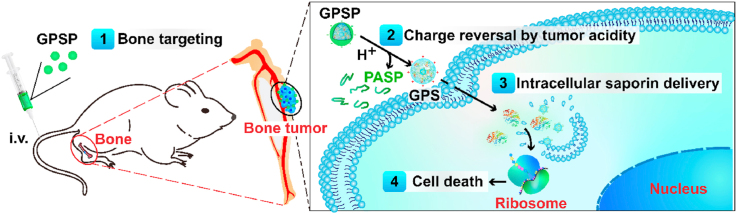

Fig. 1.

Design of bone-targeted protein nanomedicine for the treatment of malignant bone tumors. The ternary complex GPSP is consisted of an intracellular protein delivery carrier GP, a toxin protein saporin and a bone-targeted polyanion PASP. PASP on the surface enhances the accumulation of protein therapeutics in the bone tumor site, and GP facilitates the intracellular delivery of saporin protein into tumor cells. The polymer PASP on GPSP shields the positive charges on GPS nanoparticles during blood circulation, but will be detached on GPS after localization in tumor tissues triggered by tumor extracellular acidity.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Generation 5 amine-terminated polyamidoamine dendrimer (G5-NH2) with an ethylenediamine core was obtained from Dendritech Inc. (Midland, MI, USA). 4-(Bromomethyl)phenylboronic acid was purchased from Meryer Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Saporin and PASP sodium (2000–11000 Da) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Cy5.5 NHS ester was purchased from Lumiprobe (USA). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) was bought from Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Methanol and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) was purchased from Sangon Biotech. (Shanghai, China). BCA assay kit were purchased from Beyotime (Jiangsu, China).

2.2. Synthesis of boronated dendrimer

The boronated dendrimer was synthesized according to a previously reported method [12a]. 4-(Bromomethyl)phenylboronic acid (PBA) and G5-NH2 were dissolved in anhydrous methanol at a PBA/dendrimer molar ratio of 256:1 and stirred at 70 °C for 24 h. After that, the product was intensively dialyzed against methanol and distilled water using a dialysis bag (3500 Da, Biosharp, USA), followed by lyophilization to obtain G5-PBA (GP). The average number of PBA in each GP molecule is calculated to be 70 according to 1H NMR analysis (500 MHz, Varian).

2.3. Synthesis of FITC-labeled saporin (saporinFITC) and Cy5.5-labeled saporin (saporinCy5.5)

In a typical procedure, FITC was dissolved in DMSO and added into the saporin (32.8 kDa) solution (phosphate buffer saline, pH 7.4) at a FITC/saporin molar ratio of 3:1. The reaction mixture was stirred for 24 h in the dark at room temperature. The product was purified by Millipore Amicon Ultra-15 filtration device (Mw: 3000 Da) to obtain FITC-labeled saporin (saporinFITC). The protein concentration in the obtained solution was measured by a BCA assay kit. The sample was stored at −20 °C before further use. saporinCy5.5 was synthesized by the same procedure.

2.4. Synthesis and characterization of GPS and GPSP nanoformulations

GP was mixed with saporin in distilled water at a saporin/GP weight ratio of 0.75:1 for 30 min to obtain the binary complex GPS (349 nM GP and 304.9 nM saporin). Then, the anionic polymer PASP was added into the GPS solution at a PASP/GP weight ratio of 1.05:1 and the solution was incubated at room temperature for 20 min to obtain the ternary complex termed GPSP. The obtained GPS and GPSP complexes were further characterized. The morphology and size of the complexes were characterized by a transmission electron microscope (TEM) operated at 100 kV (HT7700, Hitachi, Japan). The hydrodynamic size and zeta potential of complexes were measured by Zetasizer Nano ZS90 (Malvern Instruments, UK) at 25 °C. To explore the detachment of PASP from the GPSP ternary complex nanoparticles, the zeta potential of GPSP nanoparticles (349 nM GP and 304.9 nM saporin) were measured at pH 7.5, 7.0, 6.5 and 6.0, respectively. The hydrodynamic sizes of GPS and GPSP complexes were measured at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h after preparation to evaluate the stability of nanoparticles. The complex was also diluted with distilled water containing 10% FBS and further incubated for 2 h before size measurement.

The GPSFITC complex consisting of GP and saporinFITC (34.9 nM GP and 30.5 nM saporin) were prepared as described above and characterized by a fluorescence spectrophotometer (F-4500, Hitachi, Japan). Free saporinFITC was measured as a control. The excitation wavelength is 470 nm, and the emission wavelength ranges from 475 nm to 600 nm. To mimic the release of saporin from GP triggered by anionic biomolecules, the GPSFITC complex solution was also added with heparin sodium (5 mg/mL) and the samples were incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The samples were then measured by the fluorescence spectrophotometer.

2.5. Cell culture and intracellular saporin delivery

143B cells (a human osteosarcoma cell line, ATCC) and MDA-MB-231 cells (a human breast carcinoma cell line, ATCC) stably expressing luciferase were cultured in DMEM (Gibco) and MEM (Gibco), respectively containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gemini Bio), 100 μg/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. The cells were cultured at 37 °C under 5% CO2 atmosphere in an incubator (Thermo, USA). For cell viability assay, 143B or MDA-MB-231 cells were diluted by culture medium contained 10% FBS and cultured in 96-well plates (104 cells/well) overnight. The samples including saporin (0–1 μg/mL), GPS (0–1 μg/mL saporin, the saporin/GP weight ratio is 3:4) and GPSP (0–1 μg/mL saporin, the saporin/GP/PASP weight ratio is 3:4:4.2) were diluted with serum-free culture medium, and added into the wells and incubated for 4 h with five repeats for each sample. After that, the incubation medium was replaced by fresh culture medium containing 10% FBS and the cells were further incubated for 20 h. GPSP pre-treated with serum-free culture medium at pH 6.5 for 5 min was also tested to confirm the pH-responsive behavior of the nanoparticles. A standard MTT assay was used to determine the viability of cells after treatment.

For confocal experiments, 143B cells or MDA-MB-231 cells were diluted by culture medium containing 10% FBS and cultured in confocal culture dishes (105 cells) overnight. 2.0 μg saporinFITC was mixed with 2.67 μg G5-NH2 or GP, respectively, followed by dilution with 50 μL serum-free culture media and incubation for 30 min at room temperature to obtain G5SFITC and GPSFITC, respectively. GPSFITCP was obtained by adding 2.8 μg PASP into the above GPSFITC solution and further incubated for 20 min at room temperature. After that, 950 μL serum-free culture media was added into the complex solution and mixed thoroughly before cell culture. The final concentrations of saporin, GP and PASP were 61.0 nM, 69.8 nM GP, and 430.8 nM, respectively. The samples were added into the dishes and incubated with 143B cells or MDA-MB-231 cells for 4 h. Then cells stained with Lysotracker red (DND-99, Invitrogen) and Hoechst 33342, respectively and washed with PBS buffer before observing by a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSCM, Leica SP5, Germany). To quantitatively measured the internalized saporinFITC, the cells were also cultured in 48-well plates and treated with 200 μL medium containing 0.4 μg saporinFITC, G5SFITC (0.4 μg saporinFITC and 0.53 μg G5-NH2), GPSFITC (0.4 μg saporinFITC and 0.53 μg GP) and GPSFITCP (0.4 μg SaporinFITC, 0.53 μg GP and 0.56 μg PASP), respectively for 4 h before harvesting and washed with PBS for three times. The fluorescence intensity of cells and percent of positive cells were quantitatively analyzed by flow cytometry (BD FACSCalibur, San Jose).

2.6. Bone-binding affinity of GPSP

The binding affinity of GPS and GPSP on highly-crystallized hydroxyapatite tablets and isolated tibias from mice were investigated. The hydroxyapatite tablets gifted from Prof. Kaili Lin at the Ninth People's Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University were immersed in 2 mL solutions containing saporin (1 μg/mL), GPS (1 μg/mL saporin, 1.34 μg/mL GP) and GPSP (1 μg/mL saporin, 1.34 μg/mL GP, and 1.4 μg/mL PASP), respectively for 24 h followed by washing with distilled water and drying in air. Hydroxyapatite tablets incubated with distilled water was tested as a blank control. After that, a scanning electron microscope (SEM, S4800, Hitachi, Japan) operated at 3 kV was employed to characterize of the adsorbed nanoparticles on the hydroxyapatite tablets. To visualize the adsorbed nanoparticles on the tablets, saporin was labeled with Cy5.5 and further complexed into GPSCy5.5 and GPSCy5.5P, respectively. The adsorption procedures were the same as described above. An in vivo imaging system (IVIS, Lumina-II, Caliper Life Sciences) was employed to image the hydroxyapatite tablets adsorbed with saporinCy5.5. The relative radiant efficiency on the tablets were quantitatively measured by IVIS. Similarly, tibias collected from health nude mice and bone tumor-bearing mice were incubated with GPSCy5.5 and GPSCy5.5P solutions, respectively, at equal concentrations as described above for 24 h. After washing with distilled water, the tibias were imaged and quantitatively analyzed by IVIS. Three repeats were conducted for each sample.

2.7. Biodistribution of GPSCy5.5 and GPSCy5.5P

The animal experiments were conducted according to the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and approved by the ethics committee of East China Normal University. 4-Week-old male BALB/c nude mice were bought from SLAC Laboratory Animal Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). 143B cells (2 × 105 in 20 μL PBS) stably expressing luciferase were injected into the medullary cavity of the right tibias by a sterile insulin syringe to establish the osteosarcoma model. Two weeks post-injection, each mouse was intraperitoneally injected with D-luciferin (3 mg in 200 μL PBS) and imaged by IVIS. The mice with similar luminescence intensities were chosen for further studies. Two mice were intravenously injected with 150 μL GPSCy5.5 (100 μg/kg saporinCy5.5 and 133.3 μg/kg GP) and GPSCy5.5P (100 μg/kg saporinCy5.5, 133.3 μg/kg GP and 140 μg/kg PASP), respectively. The mice were monitored by IVIS at 3 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h and 72 h post-injection. To quantitatively analyze the intensity of Cy5.5 fluorescence in the tissues, the residual mice were randomly divided into two groups with five mice in each group, and intravenously injected with 150 μL GPSCy5.5 (100 μg/kg saporinCy5.5 and 133.3 μg/kg GP) and GPSCy5.5P (100 μg/kg saporinCy5.5, 133.3 μg/kg GP and 140 μg/kg PASP), respectively. After 24 h, the main organs and tissues such as heart, liver, spleen, lungs, kidneys, tumor and tibias from tumor bearing legs were harvested, and imaged by IVIS.

2.8. Treatment of malignant bone tumors by GPSP nanoparticles

The orthotopic osteosarcoma model was established using 143B cells as described above. The mice with similar luminescence intensities at tumor site were rationally divided into five groups (five mice in each group) and intravenously injected with 150 μL PBS, GP (133.3 μg/kg), saporin (100 μg/kg), GPS (100 μg/kg saporin and 133.3 μg/kg GP) and GPSP (100 μg/kg saporin, 133.3 μg/kg GP and 140 μg/kg PASP), respectively. The treatments were repeated every other day with a total number of six injections, and the mice were imaged and quantitatively analyzed by IVIS before the first injection, after the third and sixth injection, respectively. The circumference of tumor-bearing legs and the body weight of each mouse were recorded every day. The mice were sacrificed after treatment. The tumor-bearing legs were excised from the mice bearing osteosarcoma 143B tumor, and scanned by Siemens Biograph micro-CT (Skyscan 1076, Antwerp, Belgium). A CTVox program (Bruker micro-CT NV, Antwerp, Belgium) was employed to reconstruct the 3D structure of tibias.

Bone metastatic breast cancer model was established by injection of MDA-MB-231 cells stably expressing luciferase into the medullary cavity of tibias of nude mice as described above (2 × 105 cells in 20 μL PBS). The mice with similar luminescence intensities were chosen for therapy studies. The mice were randomly divided into five groups with five mice in each group, and treated with 150 μL PBS, GP (200 μg/kg), saporin (150 μg/kg), GPS (150 μg/kg saporin and 200 μg/kg GP) and GPSP (150 μg/kg saporin, 200 μg/kg GP and 210 μg/kg PASP), respectively, with a total number of five injections. The mice were imaged and quantitatively analyzed by IVIS before the first injection, after the third and fifth injection, respectively.

2.9. Histopathological examination and apoptosis analysis

The apoptosis of cells in bone tumors were analyzed by TdT-mediated dUTP Nick-End Labeling (TUNEL) assay. The bone tumors were isolated from the tibias after micro-CT analysis, and fixed in paraffin and sectioned into slices with a thickness of 4 μm. The sections were then treated with proteinase K, Hoechst 33342 and TUNEL reaction solution according to the protocol of a Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and imaged by a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Preparation and characterization of bone-targeted protein nanoparticles

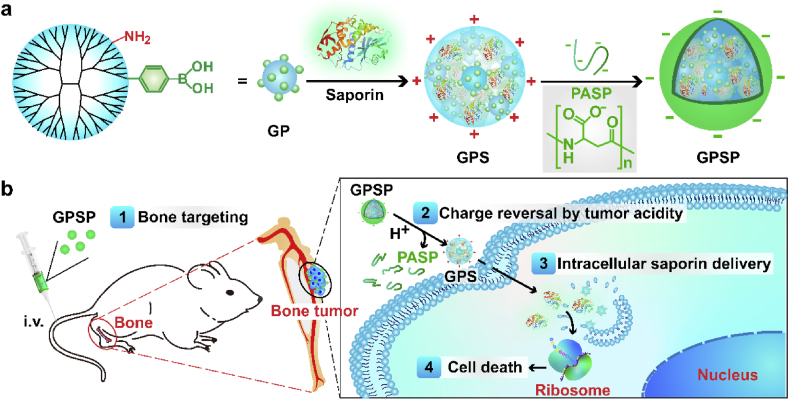

Boronated dendrimer was synthesized by reacting G5-NH2 with 4-(bromomethyl)phenylboronic acid according to a previously reported method [12a]. The average number of phenylboronic acid (PBA) ligands decorated on each G5-NH2 was 70 calculated by 1H NMR analysis (Fig. S1), and the product G5-PBA conjugate was termed GP. The complexation of GP with saporin yielded nanoparticles termed GPS. The size of GPS nanoparticles measured by dynamic light scattering was around 100 nm (Fig. 2a). Further coating of GPS nanoparticles with PASP via ionic interactions produced a ternary complex named GPSP. The size of GPS was increased after PASP coating (Fig. 2b). Both GPS and GPSP nanoparticles were stable when incubated in aqueous solutions for 72 h (Fig. 2c). GPSP also showed good stability in the presence of serum, which is probably due to the anionic nanoparticle surface (Fig. 2d). On the contrary, GPS nanoparticles with positive surface charges could interact with anionic serum proteins, and form larger aggregates in serum solutions (Fig. 2d). We further measured the zeta-potential of GPS and GPSP nanoparticles at different pH conditions. As shown in Fig. 2e, the zeta-potential of GPSP nanoparticles was gradually turned from −20 mV to about +10 mV when the solution pH was decreased from 7.4 to 6.5, suggesting the charge reversal property of GPSP triggered by tumor extracellular acidity (pH 6.2–6.8). In comparision, the value of GPS nanoparticles was only slightly changed within the pH range. This property is beneficial for targeted cancer therapy by shielding the positive charges on nanoparticles during blood circulation, while de-shielding the coating to promote tumor cell internalization after localizing in tumor tissues [13]. We further analyzed the efficacy of GPS and GPSP in the delivery of saporin into cancer cells. For visualization and quantitative analysis, saporin was labeled with fluorescein-5-isothiocyanate (saporinFITC). The prepared complexes were termed GPSFITC and GPSFITCP, respectively. The binding of saporinFITC with GP significantly quenched the fluorescence from FITC due to the formation of nanoparticles. However, the bound saporinFITC in the nanoparticles could be efficiently released in the presence of anionic polymers such as heparin (Fig. S2). Free saporinFITC and G5-NH2 complexed saporinFITC (G5SFITC) showed poor cellular uptake by osteosarcoma 143B cells, in comparison, GPSFITC was efficiently internalized into the cells (Fig. 2f). The internalized saporinFITC were not co-localized with endolysosomes stained by Lysotracker Red, suggesting efficient endosomal escape after endocytosis. Similar results were obtained on MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. S3). Though GPSFITCP nanoparticles are negatively charged, they could also be internalized by 143B cells, but the amount of internalized saporin was decreased by nearly 50% after PASP coating (Fig. 2g). The cytotoxicity of GPS and GPSP were further tested on 143B and MDA-MB-231 cells. Free saporin showed minimal toxicity on the cells at concentrations up to 1 μg/mL, however, the GPS nanoparticles efficiently killed both cells with a half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) below 0.4 μg/mL for saporin (Fig. 2h and i). After PASP coating, the toxicity of GPS nanoparticles was reduced and this result was in accordance with cellular uptake results in Fig. 2g. When pH value of the GPSP solution was changed to 6.5, the efficiency of GPSP nanoparticles on killing cancer cells was increased. This is due to the charge reversal of GPSP nanoparticles from negative to positive, which is beneficial for cell internalization.

Fig. 2.

Characterizations of GPS and GPSP nanoparticles. The hydrodynamic sizes of GPS (a) and GPSP (b), respectively. Insets are TEM images of GPS and GPSP nanoparticles, respectively. Scale bar, 100 nm. (c) The hydrodynamic sizes of GPS and GPSP measured at 0, 24, 48 and 72 h after preparation. (d) The hydrodynamic size of GPS and GPSP nanoparticles before and after incubation with 10% FBS for 2 h. (e) The zeta potentials of GPS and GPSP measured at different pH values. (f) Confocal images of 143B cells treated with SaporinFITC, G5SFITC, GPSFITC and GPSFITCP, respectively for 4 h. The endolysosomes were stained by Lysotracker red. Scale bar, 30 μm. (g) Mean fluorescence intensity of 143B cells treated with the above samples for 4 h. Viability of 143B (h) and MDA-MB-231 (i) cells treated with saporin, GPS and GPSP, respectively. GPSP pretreated with serum-free medium at pH 6.5 was also tested to confirm pH-responsiveness. **p < 0.01 analyzed by student's t-test, one tailed. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

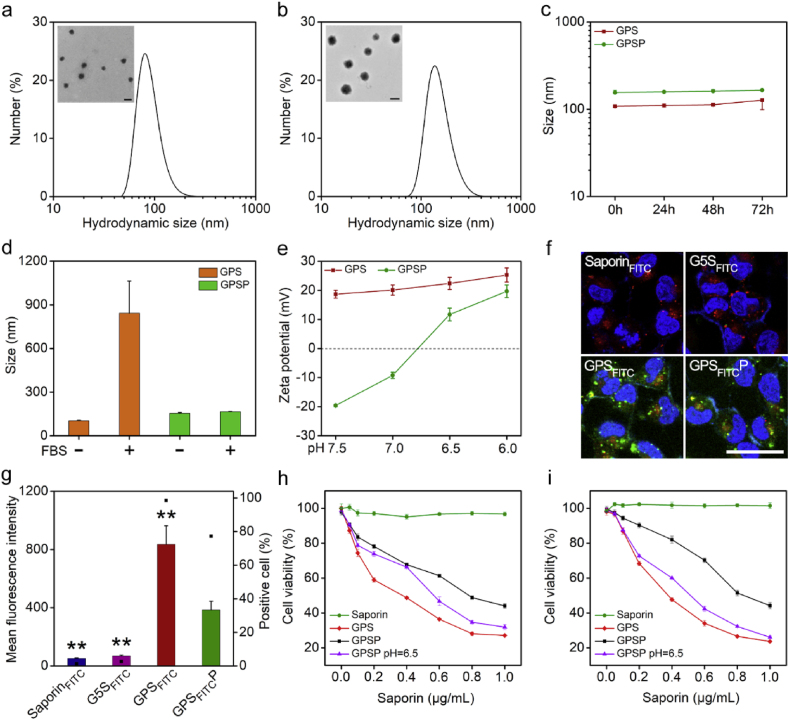

3.2. Bone targeting ability of GPSP nanoparticles

The binding ability of GPSP nanoparticles on hydroxyapatite and isolated tibias were further characterized. Free saporin and GPS nanoparticles were tested as negative controls. The nanoparticles adsorbed on hydroxyapatite tablets were directly observed by scanning electron microscope (SEM). The amount of GPSP nanoparticles adsorbed on the surface of hydroxyapatite were more than those of GPS particles (Fig. 3a). For quantitative analysis, saporin was labeled with Cy5.5 (saporinCy5.5), and the prepared complexes were termed GPSCy5.5 and GPSCy5.5P, respectively. As shown in Fig. 3b and c, the fluorescence signals on GPSCy5.5P adsorbed hydroxyapatite tablets were much stronger than those on saporinCy5.5 and GPSCy5.5P treated tablets. Similar results were obtained on isolated tibias (Fig. 3d and e). Besides, the amount of GPSCy5.5P adsorbed on tumor bearing tibias was higher than that on healthy tibias. We further investigated the in vivo biodistribution of GPSCy5.5 and GPSCy5.5P after intravenous administration (Fig. 3f). The results showed that saporinCy5.5 in GPSCy5.5 were rapidly cleared via kidney, probably due to instability of the GPS nanoparticle in the blood. After PASP coating, the kidney biodistribution of saporinCy5.5 was significantly decreased, while the amounts of protein accumulated in tumors and tumor bearing tibias were increased (Fig. 3g and h). The accumulation of GPSCy5.5P around the tumor bearing tibias was even observed at 48 h post-injection (Fig. 3f). These results clearly proved that GPSP nanoparticles have higher complex stability and bone targeting ability in vivo.

Fig. 3.

Bone-targeting capability of GPSP. (a) SEM images of hydroxyapatite tablets incubated with distilled water, saporin, GPS and GPSP, respectively for 24 h. The white arrows indicate GPS or GPSP nanoparticles adsorbed on the hydroxyapatite tablets. (b) Fluorescence images of hydroxyapatite tablets incubated with saporinCy5.5, GPSCy5.5 and GPSCy5.5P, respectively for 24 h. (c) Relative radiant efficiency of the samples in (b) measured by IVIS. (d) Fluorescence images of tibias from healthy mice and bone tumor-bearing mice incubated with GPSCy5.5 and GPSCy5.5P, respectively for 24 h. (e) Relative radiant efficiency of the samples in (d). (f) Fluorescence images of mice intravenously injected with GPSCy5.5 and GPSCy5.5P for 3, 6, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h, respectively. The red dotted circles represent the tumor sites. (g) Fluorescence images of the main organs and tissues collected from mice after treatment with GPSCy5.5 and GPSCy5.5P, respectively for 24 h. (h) Quantitative analysis of saporinCy5.5 in the main organs at 24 h post-injection. He = heart; Li = liver; Sp = spleen; Ki = kidney; Lu = lung; Tu = tumor; Ti = tibia. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 analyzed by student's t-test, one tailed. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

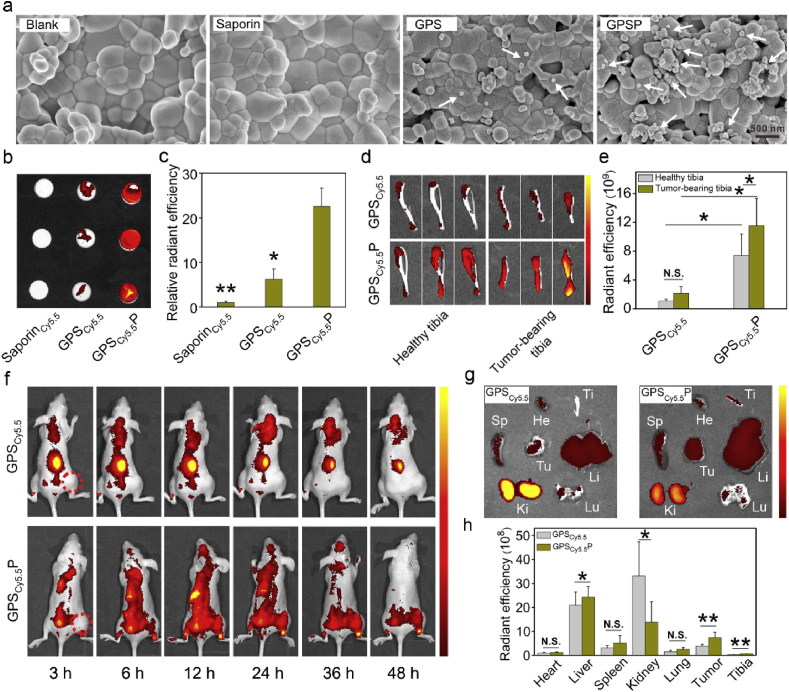

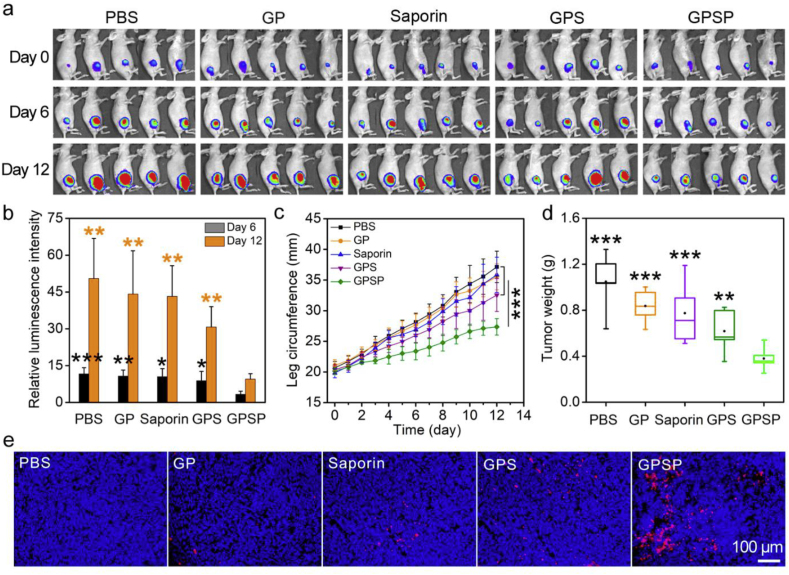

3.3. GPSP nanoparticles in the treatment of bone tumors

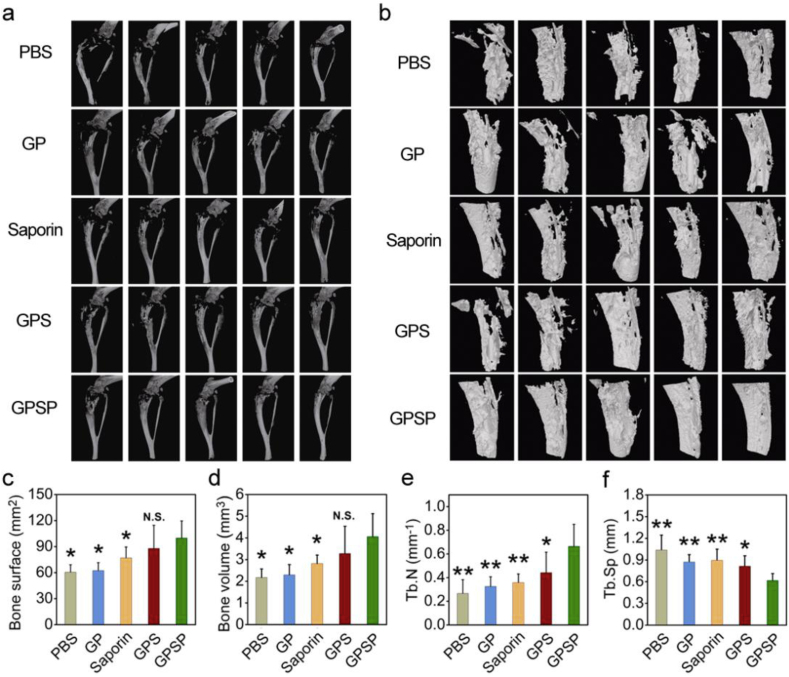

We firstly tested the therapeutic efficiency of GPSP in an osteosarcoma 143B tumor model. 143B cells stably expressing luciferase were injected into medullary cavity of the right tibias by a sterile syringe. The mice with similar luminescence intensity around the tumor bearing tibias were chosen for further studies and randomly divided into five groups. The mice were administrated with PBS, free saporin, GP, GPS and GPSP, respectively. During the treatment, the body weights of mice were scarcely changed (Fig. S4). In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS) was used to monitor the tumor growth at the sixth and twelfth day. As shown in Fig. 4a and b, the 143B tumors rapidly progressed in the control groups receiving PBS, free saporin, GP and GPS, respectively. In comparison, the growth of 143B tumors in the mice treated with GPSP was significantly inhibited according to the IVIS results. During tumor growth, circumference of the leg bearing 143B tumor was significantly increased. The increase of leg circumference of mice receiving GPSP was significantly inhibited compared to those in control groups (Fig. 4c). The weight and size of isolated tumors in the GPSP group were also lower (Fig. 4d and Fig. S5). Terminal-deoxynucleotidyl transferase mediated nick end labeling (TUNEL) analysis confirmed that the apoptosis level of tumor cells in mice treated with GPSP was the highest among the five groups (Fig. 4e). We further analyzed the isolated tibias bearing 143B tumors after treatment by micro-computed tomography (micro-CT). The results clearly showed that the bone structures in the mice treated with GPSP were maintained, while those in the control groups were severely broken (Fig. 5a and b and Fig. S6). Quantitative analysis in Fig. 5c–f demonstrated that the bone parameters including bone surface area, bone volume, trabecular number and trabecular separation were improved in mice treated with GPSP compared to those in control groups. These data proved that the GPSP nanoparticles can efficiently prevent tumor growth in osteosarcoma 143B model, and inhibit the tumor-associated osteolysis. We also tested the therapeutic efficiency of GPSP in the treatment of bone metastatic MDA-MB-231 breast cancer (Fig. S7). The luminescence intensities at tumor site were significantly increased in the PBS, GP, saproin and GPS groups during the therapeutic perioid, while the signals were much lower in the GPSP group after treatment (Fig. S7a and S7b). In addition, GPSP treatment efficiently inhibited the growth of tumors (Fig. S7c and S7d) compared to all the control groups. These results supported that GPSP treatment can also inhibit the growth of MDA-MB-231 tumors located in the tibias.

Fig. 4.

The treatment of orthotopic osteosarcoma 143B tumor by PASP. (a) Luminescence images of mice before treatment, and at day 6 and day 12 post-treatment, respectively by IVIS. (b) Relative luminescence intensities at the bone tumor site at day 6 (black) and day 12 (orange), respectively. The values were relative to those at day 0 for each group. (c) The circumference of tumor-bearing legs during the treatment period. (d) Average weight of tumors excised from the tumor-bearing legs after treatment. (e) Apoptosis of tumor cells (red) after treatment determined by TUNEL assay. The cell nuclei were stained by Hoechst 33342 (blue). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 analyzed by student's t-test, one tailed. Statistical differences for the PBS, GP, saporin and GPS groups compared to the GPSP group were analyzed. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Fig. 5.

Micro-CT analysis of the tumor-bearing tibias after treatment. (a) 3D micro-CT reconstruction of tumor-bearing tibias after treatment. (b) 3D sagittal reconstruction of tumor-bearing tibias. (c–f) Tibia parameters including bone surface (c), bone volume (d), trabecular number (e) and trabecular separation (f) in the tumor-bearing mice after treatment. N.S.p > 0.05, *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 analyzed by student's t-test, one tailed.

4. Conclusion

In summary, we reported a bone-targeted protein nanomedicine for the treatment of malignant bone tumors. The nanomedicine consisted of an intracellularly delivering polymer vector, a therapeutic cargo protein saporin, and a bone-targeting polymer PASP. The protein nanomedicine showed a charge reversal property at acidic conditions, and could be efficiently internalized into tumor cells to exert the anticancer activity. The nanomedicine displayed high binding affinity on hydroxyapatite and isolated tibias. Therapeutic results confirmed that the bone-targeted protein nanomedicine could inhibit the tumor growth in several bone tumor models. The results provide a new therapeutic option for the treatment of malignant bone tumors.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yang Yan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Lei Zhou: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Zhengwang Sun: Methodology, Data Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Dianwen Song: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Yiyun Cheng: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Interdisciplinary Program of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (ZH2018ZDA18). We are grateful for the support of ECNU Multifunctional Platform for Innovation (011), and the Flow Cytometry Core Facility at ECNU.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of KeAi Communications Co., Ltd.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.05.041.

Contributor Information

Zhengwang Sun, Email: specialsamsun@126.com.

Dianwen Song, Email: dianwen.song@shgh.cn.

Yiyun Cheng, Email: yycheng@mail.ustc.edu.cn.

Appendix B. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Chen Y., Di Grappa M.A., Molyneux S.D., McKee T.D., Waterhouse P., Penninger J.M., Khokha R. RANKL blockade prevents and treats aggressive osteosarcomas. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015;7 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad0295. 317ra197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suva L.J., Washam C., Nicholas R.W., Griffin R.J. Bone metastasis: mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2011;7:208–218. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2010.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Gao X., Li L., Cai X., Huang Q., Xiao J., Cheng Y. Targeting nanoparticles for diagnosis and therapy of bone tumors: opportunities and challenges. Biomaterials. 2021;265 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120404. 120404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Rotman S.G., Grijpma D.W., Richards R.G., Moriarty T.F., Eglin D., Guillaume O. Drug delivery systems functionalized with bone mineral seeking agents for bone targeted therapeutics. J. Contr. Release. 2018;269:88–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Cheng H., Chawla A., Yang Y., Li Y., Zhang J., Jang H.L., Khademhosseini A. Development of nanomaterials for bone-targeted drug delivery. Drug Discov. Today. 2017;22:1336–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2017.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Zhou Z., Fan T., Yan Y., Zhang S., Zhou Y., Deng H., Cai X., Xiao J., Song D., Zhang Q., Cheng Y. One stone with two birds: phytic acid-capped platinum nanoparticles for targeted combination therapy of bone tumors. Biomaterials. 2019;194:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wang Y., Jiang C., He W., Ai K., Ren X., Liu L., Zhang M., Lu L. Targeted imaging of damaged bone in vivo with gemstone spectral computed tomography. ACS Nano. 2016;10:4164–4172. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b07401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Yan Y., Gao X., Zhang S., Wang Y., Zhou Z., Xiao J., Zhang Q., Cheng Y. A carboxyl-terminated dendrimer enables osteolytic lesion targeting and photothermal ablation of malignant bone tumors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11:160–168. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b15827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Thamake S.I., Raut S.L., Gryczynski Z., Ranjan A.P., Vishwanatha J.K. Alendronate coated poly-lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) nanoparticles for active targeting of metastatic breast cancer. Biomaterials. 2012;33:7164–7173. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yin Q., Tang L., Cai K., Tong R., Sternberg R., Yang X., Dobrucki L.W., Borst L.B., Kamstock D., Song Z., Helferich W.G., Cheng J., Fan T.M. Pamidronate functionalized nanoconjugates for targeted therapy of focal skeletal malignant osteolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Unit. States Am. 2016;113:E4601–E4609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603316113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang C., Li L., Zhang S., Yan Y., Huang Q., Cai X., Xiao J., Cheng Y. Carrier-free platinum nanomedicine for targeted cancer therapy. Small. 2020;16 doi: 10.1002/smll.202004829. e2004829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Sun W., Ge K., Jin Y., Han Y., Zhang H., Zhou G., Yang X., Liu D., Liu H., Liang X.J., Zhang J. Bone-targeted nanoplatform combining zoledronate and photothermal therapy to treat breast cancer bone metastasis. ACS Nano. 2019;13:7556–7567. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b00097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wang Y., Yang J., Liu H., Wang X., Zhou Z., Huang Q., Song D., Cai X., Li L., Lin K., Xiao J., Liu P., Zhang Q., Cheng Y. Osteotropic peptide-mediated bone targeting for photothermal treatment of bone tumors. Biomaterials. 2017;114:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y., Huang Q., He X., Chen H., Zou Y., Li Y., Lin K., Cai X., Xiao J., Zhang Q., Cheng Y. Multifunctional melanin-like nanoparticles for bone-targeted chemo-photothermal therapy of malignant bone tumors and osteolysis. Biomaterials. 2018;183:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li C.Y., Zhang Y.J., Chen G.C., Hu F., Zhao K., Wang Q.B. Engineered multifunctional nanomedicine for simultaneous stereotactic chemotherapy and inhibited osteolysis in an orthotopic model of bone metastasis. Adv. Mater. 2017;29 doi: 10.1002/adma.201605754. 1605754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Lv J., Fan Q., Wang H., Cheng Y. Polymers for cytosolic protein delivery. Biomaterials. 2019;218 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119358. 119358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Cheng Y. Design of polymers for intracellular protein and peptide delivery. Chin. J. Chem. 2021;39:1443–1449. [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Zhang Z., Shen W., Ling J., Yan Y., Hu J., Cheng Y. The fluorination effect of fluoroamphiphiles in cytosolic protein delivery. Nat. Commun. 2018;9 doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03779-8. 1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chang H., Lv J., Gao X., Wang X., Wang H., Chen H., He X., Li L., Cheng Y. Rational design of a polymer with robust efficacy for intracellular protein and peptide delivery. Nano Lett. 2017;17:1678–1684. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b04955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ren L.F., Lv J., Wang H., Cheng Y.Y. A coordinative dendrimer achieves excellent efficiency in cytosolic protein and peptide delivery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:4711–4719. doi: 10.1002/anie.201914970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Zhang S., Shen J., Li D., Cheng Y. Strategies in the delivery of Cas9 ribonucleoprotein for CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. Theranostics. 2021;11:614–648. doi: 10.7150/thno.47007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Rong G., Wang C., Chen L., Yan Y., Cheng Y. Fluoroalkylation promotes cytosolic peptide delivery. Sci. Adv. 2020;6 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz1774. eaaz1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Xu J., Lv J., Zhuang Q., Yang Z., Cao Z., Xu L., Pei P., Wang C., Wu H., Dong Z., Chao Y., Wang C., Yang K., Peng R., Cheng Y., Liu Z. A general strategy towards personalized nanovaccines based on fluoropolymers for post-surgical cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020;15:1043–1052. doi: 10.1038/s41565-020-00781-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Lv J., Cheng Y. Fluoropolymers in biomedical applications: state-of-the-art and future perspectives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021;50(9):5435–5467. doi: 10.1039/d0cs00258e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Yang W., Wei Y., Yang L., Zhang J., Zhong Z., Storm G., Meng F. Granzyme B-loaded, cell-selective penetrating and reduction-responsive polymersomes effectively inhibit progression of orthotopic human lung tumor in vivo. J. Contr. Release. 2018;290:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Yu J., Yang W., Zhang J., Meng F., Zhong Z. Protein toxin chaperoned by LRP-1-targeted virus-mimicking vesicles induces high efficiency glioblastoma therapy in vivo. Adv. Mater. 2018;30 doi: 10.1002/adma.201800316. 1800316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Posey N.D., Tew G.N. Associate and dissociative processes in non-covalent polymer mediated intracellular protein delivery. Chem. Asian J. 2018;13:3351–3365. doi: 10.1002/asia.201800849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k) He H., Chen Y., Li Y., Song Z., Zhong Y., Zhu R., Cheng J., Yin L. Effective and selective anti-cancer protein delivery via all-functions-in-one nanocarriers coupled with visible light-responsive, reversible protein engineering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018;28 1706710. [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Liu C., Wan T., Wang H., Zhang S., Ping Y., Cheng Y. A boronic acid-rich dendrimer with robust and unprecedented efficiency for cytosolic protein delivery and CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. Sci. Adv. 2019;5 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw8922. eaaw8922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lv J., Wang C., Li H., Li Z., Fan Q., Zhang Y., Li Y., Wang H., Cheng Y. Bifunctional and bioreducible dendrimer bearing a fluoroalkyl tail for efficient protein delivery both in vitro and in vivo. Nano Lett. 2020;20:8600–8607. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c03287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lv J., Liu C., Lv K., Wang H., Cheng Y. Boronic acid-rich dendrimer for efficient intracellular peptide delivery. Sci. China Mater. 2019;63:620–628. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y., Song Z., Zheng N., Nagasaka K., Yin L., Cheng J. Systemic siRNA delivery to tumors by cell-penetrating α-helical polypeptide-based metastable nanoparticles. Nanoscale. 2018;10:15339–15349. doi: 10.1039/c8nr03976c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.