Abstract

Background

The impact of prior fragility fractures and osteoporosis treatment before total hip arthroplasty (THA) on postoperative complications is unclear. The purpose of this study was to characterize the effect of prior fragility fractures and preoperative osteoporosis treatment on short-term complications and secondary fragility fractures after THA.

Methods

A propensity score–matched retrospective cohort study was conducted using a commercially available database to (1) characterize the impact of prior fragility fractures on rates of short-term complications after THA and (2) evaluate if osteoporosis treatment before arthroplasty reduces risk of postoperative complications. Rates of periprosthetic fracture, revision THA, and fragility fractures were compared via multivariable logistic regression.

Results

After 1:1 propensity score matching, 2188 patients were assigned to each cohort. Patients with a fragility fracture in the 3 years preceding THA were more likely to sustain a periprosthetic fracture (1 year: 1.7% vs 1.0%, odds ratio [OR] 1.89; 2 years: 2.1% vs 1.1%, OR 1.82), fragility fracture (1 year: 4.7% vs 1.1%, OR 3.59; 2 years: 6.7% vs 1.7%, OR 3.21), and revision THA (1 year: 2.7% vs 1.7%, OR 1.65; 2 years: 3.1% vs 1.9%, OR 1.58). Among patients with a prior fragility fracture, only 13.8% received osteoporosis pharmacotherapy before THA. Rates of all complications were statistically comparable postoperatively for patients with and without pre-THA osteoporosis treatment.

Conclusions

Fragility fractures within 3 years before THA are associated with significantly increased risk of periprosthetic fracture, all-cause revision, and secondary fragility fractures postoperatively. Preoperative osteoporosis treatment may not decrease risk of postoperative complications.

Keywords: Fragility, Fracture, Treatment, Arthroplasty, Hip, Osteoporosis

Introduction

Osteoporosis affects more than 54 million Americans and is the most prevalent chronic musculoskeletal condition worldwide [1]. Characterized by the loss of structural integrity of trabecular bone, it is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a bone mineral density T-score less than −2.5 via dual-emission x-ray absorptiometry, which predisposes an individual to an increased risk of fracture [[2], [3], [4]]. Fragility fractures, which are those caused by low-impact trauma equal to a fall from standing height or less, represent a significant and growing cause of morbidity in the United States [2,5]. The lifetime risk of sustaining a fragility fracture has been estimated to be as high as 50% for women and 22% for men [6]. Between 2013 and 2014, fragility fractures were responsible for more than 540,600 hospitalizations and 935,700 visits to an emergency department by Americans aged 50 and older [5]. Notably, these rates are likely a significant underestimate, and the true incidence of fragility fractures is likely much higher given the frequency of incidental diagnoses, asymptomatic fractures, and increasing prevalence of osteoporosis in an expanding elderly population [3,[7], [8], [9]].

Fragility fractures tend to occur at sites with high proportions of trabecular bone, and the most commonly affected skeletal areas include the hip, humerus, wrist, femur, and vertebral column [5,10,11]. Morbidity and mortality escalate substantially after a fracture, and many patients experience long-term deficits in mobility, function, and quality of life [5,11]. Hip fractures are particularly pernicious accounting for 14% of all fractures, yet responsible for 72% of related health-care expenditure [12]. Patients with hip fracture exhibit up to an eight-fold increase in all-cause mortality for the 3 months in the acute postoperative setting and a mortality rate up to 30% within 1 year [13,14]. A prior fragility fracture has been demonstrated to be strongly predictive of a future fragility fracture [15]. A recent study found that 11.3% of patients who sustained a fragility fracture suffered a second fragility fracture within 3 years, nearly 58% of which involved the hip independent of initial fracture site [9].

Periprosthetic fractures have been broadly observed to occur after less than 1% of total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty; however, they are associated with significantly increased mortality [16]. Short-term morbidity is significantly higher than that experienced after native hip fractures, and the 5-year mortality risk for patients undergoing revision THA for periprosthetic fracture has been reported to be 60% for high-risk patients [17,18]. Two well-documented risk factors for periprosthetic fracture are osteoporosis and advanced age [16]. Seventy-five percent of periprosthetic fractures are reportedly caused by low-energy trauma, mirroring the etiology of fragility fractures [16]. As over 90% of THA are performed on patients older than 50 years, an estimated 25% of patients undergoing THA have an osteoporosis diagnosis at the time of surgery [[19], [20], [21]]. While substantial evidence exists linking osteoporosis and advanced age to periprosthetic fracture after total joint arthroplasty, the impact of a prior fragility fracture on the prevalence of similar postoperative complications has not been studied.

The purpose of this study was to characterize the effect of a prior fragility fracture on rates of short-term joint complications and incident fragility fractures including periprosthetic fractures after primary THA. We hypothesize that a prior fragility fracture is associated with increased risk of postoperative periprosthetic fracture and revision THA at medium-term follow-up. A secondary goal was to determine if osteoporosis pharmacotherapy before THA reduces the risk of postoperative complications and secondary fragility fractures among patients with a recent history of fragility fracture.

Material and methods

Patient records were queried from PearlDiver (PearlDiver Inc., Fort Wayne, IN), a commercially available administrative claims database of deidentified inpatient and outpatient data. Current Procedural Technology (CPT) and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revision (ICD-9/ICD-10), diagnosis codes were used to identify eligible patients and outcomes. The database contains the medical records of approximately 122 million patients across the United States from 2010 through 2019 which are collected by an independent data aggregator. All payors including commercial, private, and government health plans are represented. Institutional review board exemption was granted for this study as provided data were deidentified and compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. For the sake of protecting patient identities, the PearlDiver software only reports exact patient counts when defined groups have at least 11 patients; if defined cohorts are smaller, “−1” is reported. When such instances arose in the present study, a value of 5 (median between 1 and 10) was assigned for the patient count. No outside funding from the commercial, government, or nonprofit sectors was received for this study.

A propensity score–matched retrospective cohort study was conducted to (1) characterize the impact of prior fragility fractures on rates of short-term complications after primary THA (CPT-27,130) and (2) evaluate if osteoporosis treatment before arthroplasty reduces risk of postoperative complications among patients with prior fragility fractures. Fragility fractures were defined by ICD-9/10 diagnosis codes for primary closed fractures of the hip, wrist, spine, pelvis, and humerus. Hip fragility fractures were defined by ≥1 inpatient claim(s) (any diagnostic position), while all other fracture locations were defined by either (1) ≥1 inpatient claim(s) (any diagnostic position) or (2) ≥1 outpatient claim(s). In addition, to ensure the fragility-based etiology of the fractures, fractures with an ICD trauma code on a claim within 7 days before or 7 days after the index fracture claim were excluded. A history of fragility fracture was defined as at least one of the aforementioned criteria within 3 years before joint replacement.

Prearthroplasty osteoporosis pharmacotherapy criteria were defined by at least one drug claim between the dates of the prior fragility fracture and joint replacement. Generic drug codes were used to identify prescription claims filed for the following medications: alendronate, risedronate, ibandronate, zoledronic acid, raloxifene, denosumab, teriparatide, abaloparatide, and calcitonin. These codes are cross-mapped to eleven-digit National Drug Codes on patients’ charging records. A full list of fracture diagnosis codes and drug codes used is provided in Supplemental Table 1.

In order to limit potential transfer bias due to patients leaving or joining the data set during the follow-up period, only patients with continuous database enrollment for at least 2 years after arthroplasty were included. As such, to capture a 3-year preoperative period of fragility fracture history and a 2-year follow-up for evaluating complications, only primary THAs performed on patients aged 50 years and older between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2017, were included in the analysis. In order to ensure complications tied to the index THA, patients with contralateral hip surgery including but not limited to THA, hemiarthroplasty, and conversion to THA during the 2-year follow-up were excluded. Patients with metastatic cancer, infectious indications, contraindications to first-line pharmacotherapy for osteoporosis (eg, Roux-en-Y bypass for bisphosphonates), and various metabolic diseases that predispose to low bone density were excluded. In addition, to capture only elective THA cases, patients with a hip fracture claim within 30 days before or on the same day as THA were excluded. A complete list of codes used to define inclusion/exclusion criteria is available in Supplemental Table 1.

Rates of postoperative complications after THA were compared for (1) patients with and without a prior fragility fracture, and (2) among patients with a prior fragility fracture, patients with and without osteoporosis treatment before THA. Complications assessed included periprosthetic fracture, all-cause revision joint arthroplasty, and fragility fractures at 1 and 2 years postoperatively. Fragility fractures during the follow-up period were defined using the same criteria as preoperative fractures. The diagnostic and procedural codes used to define each complication are available in Supplemental Table 2.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software (R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) integrated within the PearlDiver software with an α level set to 0.05. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were obtained for all patients, including age, sex distribution, body mass index (BMI), insurance plan type, United States region, average Elixhauser Comorbidity Index score, and major comorbidities. Categorical variables were compared with chi-square analysis, and continuous variables were compared with Welch’s t test or the Mann-Whitney U test.

For comparing outcomes among patients with and without a prior fragility fracture, propensity score matching was performed using a logistic regression model accounting for the following clinical variables: age, gender, insurance plan type, US region, diabetes mellitus, tobacco use, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic kidney disease, and dementia. Propensity scores represent the conditional probability of assignment to a “test” group and can be used to control for multiple observed covariates that are associated with both the exposure and outcome. The propensity score was used to match patients with a prior fragility fracture and patients with no fracture history using a fixed 1:1 ratio and a caliper of 0.20 to achieve nearest neighbor matching without replacement. Rates of postoperative complications were compared with multivariable logistic regression controlling for age, gender, Elixhauser Comorbidity Index score, and baseline diagnoses of rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, and dementia to calculate adjusted odds ratios with corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

Matching was not performed for the secondary analysis of osteoporosis treatment before joint replacement because of small sample sizes of the treatment cohorts, which would prevent adequate statistical power from being achieved. Rates of postoperative complications for patients with vs without osteoporosis treatment before THA were compared with multivariable logistic regression controlling for the same variables mentioned previously. Post hoc power analyses were performed for the primary and secondary outcomes to assess power at an α of 0.05.

Results

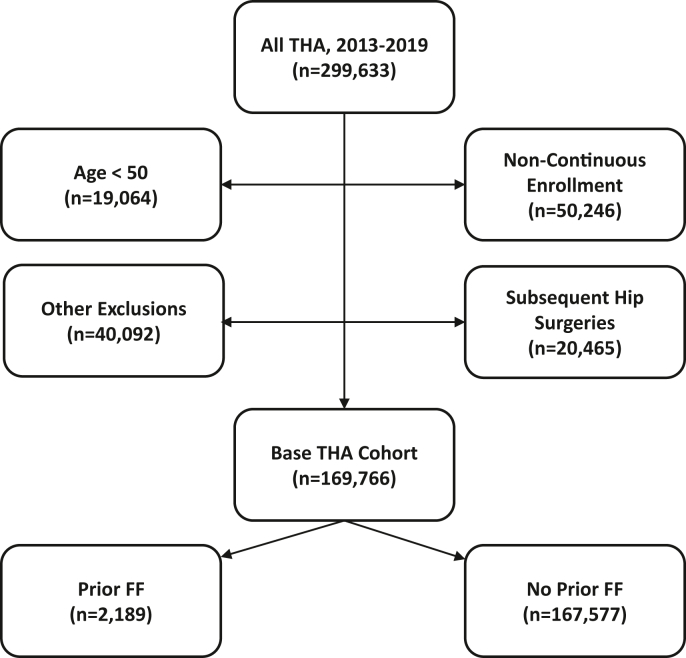

A total of 169,766 patients who underwent THA met all inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Within this cohort, 2189 (1.3%) patients had a prior fragility fracture in the last 3 years while 167,577 (98.7%) patients did not. There were considerable baseline demographic differences between the patient populations with vs without prior fragility fractures, including average age, patient sex distribution, region, plan type, and prevalence of major comorbidities (Table 1). Following 1:1 propensity score matching, 2188 patients were assigned to each cohort. Matching eliminated much of the baseline differences yielding comparable base populations. Despite matching, a significantly greater proportion of patients with a prior fragility fracture had a diagnosis of dementia (2.5% vs 1.1%, P < .001). Other baseline diagnoses significantly more prevalent in the cohort with a prior fragility fracture after matching included osteoporosis diagnoses (24.9% vs 6.3%, P < .001) and vitamin D deficiency (23.7% vs 18.7%, P < .001).

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing identification of base unmatched THA cohorts. FF, fragility fracture.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic data for unmatched and matched THA cohorts.

| Characteristics | Unmatched |

Matched |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior FF |

No prior FF |

P value | Prior FF |

No prior FF |

P value | |

| (n = 2189) | (n = 167,577) | (n = 2188) | (n = 2188) | |||

| Sex, female (%) | 1587 (72.5) | 94640 (56.5) | <.001 | 1586 (72.5) | 1602 (73.2) | .61 |

| Age, mean ± SD | 69.0 ± 7.7 | 66.4 ± 8.1 | <.001 | 69.1 ± 7.7 | 68.9 ± 7.8 | .521 |

| Age range (%) | ||||||

| 50-59 | 325 (14.8) | 39760 (23.7) | <.0001 | 325 (14.9) | 338 (15.4) | .613 |

| 60-69 | 669 (30.6) | 61029 (36.4) | <.001 | 669 (30.6) | 666 (30.4) | .948 |

| 70-74 | 342 (15.6) | 25418 (15.2) | .580 | 342 (15.6) | 337 (15.4) | .867 |

| 75+ | 853 (39.0) | 41370 (24.7) | <.001 | 852 (38.9) | 847 (38.7) | .901 |

| Plan type (%) | ||||||

| Cash | 5a (0.2) | 134 (0.08) | <.001 | 5a (0.23) | 5a (0.23) | 1 |

| Commercial | 1336 (61.0) | 108356 (64.7) | .94 | 1336 (61.1) | 1319 (60.3) | .621 |

| Government | 28 (1.3) | 2935 (1.8) | .32 | 28 (1.3) | 26 (1.2) | .891 |

| Medicaid | 67 (3.1) | 3538 (2.1) | .57 | 66 (3.0) | 54 (2.5) | .309 |

| Medicare | 747 (34.1) | 51246 (30.6) | <.001 | 747 (34.1) | 782 (35.7) | .281 |

| Unknown | 5a (0.2) | 1368 (0.8) | 1 | 5a (0.23) | 5a (0.23) | .422 |

| BMI (%)b | ||||||

| <30 | 440 (20.1) | 24223 (14.5) | .11 | 440 (20.1) | 391 (17.9) | .064 |

| 30-35 | 298 (13.6) | 22948 (13.7) | <.001 | 298 (13.6) | 312 (14.3) | .571 |

| 35-40 | 203 (9.3) | 16650 (9.9) | <.001 | 203 (9.3) | 217 (9.9) | .505 |

| >40 | 184 (8.4) | 14705 (8.8) | .05 | 183 (8.4) | 159 (7.3) | .195 |

| Region (%) | ||||||

| Northeast | 396 (18.1) | 50625 (30.2) | <.001 | 396 (18.1) | 384 (17.6) | .664 |

| South | 642 (29.3) | 36478 (21.8) | <.001 | 642 (29.3) | 650 (29.7) | .817 |

| Midwest | 854 (39.0) | 58395 (34.8) | <.001 | 853 (39.0) | 863 (39.4) | .781 |

| West | 294 (13.4) | 21900 (13.1) | .64 | 294 (13.4) | 287 (13.1) | .789 |

| N/A | 5a (0.2) | 179 (0.1) | .92 | 5a (0.23) | 5a (0.23) | 1 |

| Osteoporosis diagnosis (%) | 546 (24.9) | 6542 (3.9) | <.001 | 545 (24.9) | 137 (6.3) | <.001 |

| ECI, mean ± SD | 7.8 ± 4.2 | 5.6 ± 3.6 | <.001 | 7.8 ± 4.2 | 6.4 ± 3.7 | <.001 |

| Comorbidities (%) | ||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 939 (42.9) | 65311 (39.0) | <.001 | 938 (42.9) | 944 (43.1) | .879 |

| Vitamin D deficiency | 520 (23.8) | 27568 (16.5) | <.001 | 519 (23.7) | 410 (18.7) | <.001 |

| Tobacco use | 833 (38.0) | 39656 (23.7) | <.001 | 832 (38.0) | 825 (37.7) | .852 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 220 (10.0) | 9547 (5.7) | <.001 | 219 (10.0) | 231 (10.6) | .584 |

| Dementia | 56 (2.6) | 1150 (0.7) | <.001 | 55 (2.5) | 24 (1.1) | <.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 292 (13.3) | 13259 (7.9) | <.001 | 292 (13.3) | 243 (11.1) | .027 |

ECI, Elixhauser Comorbidity Index; FF, fragility fracture; SD, standard deviation.

Exact counts under 11 are unavailable in PearlDiver. A patient count of 5 (median between 1 and 10) was assigned in such instances.

BMI data was available for 51% and 47% of unmatched patients with and without a prior fragility fracture, respectively; BMI data was available for 51% and 49% of matched patients with and without a prior fragility fracture, respectively.

Outcomes were compared for patients with and without a prior fragility fracture at 1 and 2 years postoperatively (Table 2). After THA, periprosthetic fractures, secondary fragility fractures, and all-cause revision were all significantly more likely at both 1 and 2 years for patients with a history of fragility fractures (all P < .05). A post hoc power analysis of each primary outcome showed that the study was adequately powered (>90%) to detect significant differences in rates of all outcomes.

Table 2.

Outcomes at 1 and 2 years postoperatively for matched THA cohorts, history of fragility fracture vs no prior fragility fracture.

| Complication | Prior FF (n = 2188) | No prior FF (n = 2188) | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPFx, n (%) | |||

| 1 y | 38 (1.7) | 21 (1.0) | 1.89 (1.10-3.33) |

| 2 y | 47 (2.1) | 25 (1.1) | 1.82 (1.11-3.06) |

| FF, n (%) | |||

| 1 y | 103 (4.7) | 25 (1.1) | 3.59 (2.31-5.78) |

| 2 y | 147 (6.7) | 38 (1.7) | 3.21 (2.23-4.74) |

| Revision, n (%) | |||

| 1 y | 60 (2.7) | 37 (1.7) | 1.65 (1.08-2.55) |

| 2 y | 67 (3.1) | 42 (1.9) | 1.58 (1.06-2.39) |

CI, confidence interval; FF, fragility fracture; PPFx, periprosthetic fracture; revision, all-cause revision THA; OR, odds ratio.

Among the 2189 patients that underwent THA and had a prior fragility fracture, 303 (13.8%) filed at least one claim for osteoporosis pharmacotherapy between their fracture and THA (Table 3). Alendronate was the most common medication on claims filed (64.7%) in the treatment cohort (Supplementary Table 3). At 1-year follow-up, rates of periprosthetic fracture, secondary fragility fractures, and revision THA were higher in the treatment group. At 2 years, rates of periprosthetic fracture and revision THA were lower in the treatment group while the rate of secondary fragility fractures was higher. However, all outcomes were statistically comparable at both 1 and 2 years postoperatively for the treatment vs no treatment cohorts. Post hoc power analyses showed that the sample sizes are likely underpowered (<80%) to detect significant differences for all secondary outcomes.

Table 3.

Outcomes for patients with a fragility fracture history, received treatment vs no treatment before total hip arthroplasty.

| Complication | Treatment (n = 303) | No treatment (n = 1886) | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPFx, n (%) | |||

| 1 y | 5a (1.7) | 32 (1.7) | 1.41 (0.51-3.33) |

| 2 y | 5a (1.7) | 41 (2.2) | 0.91 (0.34-2.09) |

| FF, n (%) | |||

| 1 y | 21 (6.9) | 82 (4.3) | 1.23 (0.71-2.03) |

| 2 y | 29 (9.6) | 118 (6.3) | 1.16 (0.73-1.80) |

| Revision, n (%) | |||

| 1 y | 5a (1.7) | 51 (2.7) | 1.03 (0.46-2.08) |

| 2 y | 5a (1.7) | 58 (3.1) | 0.89 (0.40-1.77) |

CI, confidence interval; FF, fragility fracture; PPFx, periprosthetic fracture; revision, all-cause revision THA; OR, odds ratio.

Exact counts under 11 are unavailable in PearlDiver. A patient count of 5 (median between 1 and 10) was assigned in such instances.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that a history of fragility fracture correlates with increased rates of complications after THA. Among patients who underwent THA, periprosthetic fractures and fragility fractures were significantly more likely at both 1 and 2 years postoperatively for patients with a prior fragility fracture. Furthermore, all-cause revision after THA was also significantly more likely for patients with a previous fragility fracture at both postoperative intervals. In patients who underwent THA with a history of fragility fracture, rates of periprosthetic fracture, secondary fragility fractures, and all-cause revision were statistically comparable at both 1 and 2 years postoperatively between patients that filed at least one claim for osteoporosis pharmacotherapy before THA and patients that did not receive pharmacotherapy. However, post hoc power analyses showed that the study was underpowered to evaluate these secondary outcomes.

Surgeons make decisions during THA regarding hip stem geometry and method of fixation such that understanding the risk profile of each patient is paramount. In patients undergoing THA with Dorr type C bone or increased risk of fracture, surgeons may choose press-fit femoral stem geometries that have increased stability to rotational and axial forces [22]. In patients with severely compromised bone and risk factors, cemented stems or prophylactic cerclage wires may be indicated [23]. The present study found significantly increased risk of periprosthetic fracture, fragility fracture, and all-cause revision for patients with a history of fragility fracture as compared to matched controls with no fracture history. This result highlights the significance of fragility fractures with respect to preoperative risk stratification, patient counseling, and intraoperative planning. Certain comorbidities such as dementia have also been linked to significantly higher risk of falls and secondary fragility fractures [24]. As higher rates of dementia persisted in the cohort with a prior fragility fracture despite matching across this diagnosis, identification of dementia as a risk factor for falls and related sequelae even in the absence of prior fragility fractures may be warranted. In addition, only 13.8% of patients with a fragility fracture filed a claim for pharmacologic therapy after a fragility fracture even with documented treatment by an orthopedic surgeon for a subsequent elective THA. However, this study demonstrated that short-term implementation of pharmacotherapy did not decrease the periprosthetic fracture risk in patients who had fragility fractures before THA. This suggests that once a patient has a fragility fracture, selection of implant type and fixation method remains important despite short-term pharmacotherapy.

The findings of the present study suggest that initiating pharmacotherapy after a fragility fracture may not decrease the risk of complications after a fragility fracture and supports efforts of the Own the Bone program to have both male and female patients screened for osteoporosis at the appropriate age as a preventative tool [25]. These medications may take longer to provide a protective benefit after a fragility fracture, or may not be able to restore bone quality of this population to a level equivalent to patients without prior fragility fracture. However, as the treatment cohort in this study was defined as patients with a fragility fracture at any point within 3 years before THA and at least one subsequent pharmacologic claim, a wide range of possible treatment lengths were included. Therefore, our results do not rule out potential risk reduction with osteoporosis treatment after a fragility fracture but instead suggest prearthroplasty treatment alone may not reduce risk of THA complications for patients with a prior fracture within 3 years and with at least minimal treatment exposure before THA. The inadequate power (<80%) of the sample sizes in the secondary analysis further reinforces the inability to make definitive claims regarding the utility of prearthroplasty short-term osteoporosis treatment. Future randomized controlled trials are warranted to ascertain the potential of preoperative osteoporosis treatment protocols in reducing postoperative complications after THA and to investigate the impact of fragility fractures on the efficacy of such interventions.

There are several limitations to this study. First, as the PearlDiver database only provides data on a particular group of patients during a specific time period, sampling bias is present. By only measuring joint complications 2 years after the index arthroplasty procedure, this analysis is limited to short-term data and excludes long-term complications. With the complex nature of medical billing, there is a possibility of coding bias through manual entry of diagnosis/procedural codes. Furthermore, as this study includes patient data from both before and after 2015, both ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes were used. As diagnosis codes do not match exactly across ICD-9 and ICD-10, a translator application was used to identify corresponding codes. Coding errors are inherent with any analysis of administrative claims data; however, a study by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid demonstrates such instances made up only 1.0% of payments in 2019 [26]. In addition, by limiting the preoperative window to 3 years for fragility fracture evaluation, it is possible some patients in the “non-fragility fracture” cohort had a prior fragility fracture before this period. Furthermore, as prior literature shows only one in 3 vertebral fractures are clinically identified, more patients could have had prior undiagnosed fragility fractures [27]. An additional limitation is that, by defining prearthroplasty pharmacotherapy exposure as at least one claim for any osteoporosis medication at any time between the dates of the index fracture and THA, it is possible that some patients included in the “treatment” cohort did not receive clinically adequate treatment exposure. As the benefit of osteoporosis medications is well-established, this limitation may misconstrue the potential impact of preoperative osteoporosis treatment on reducing rates of postoperative complications. Furthermore, although the power analysis showed the number of patients included in the primary analysis possessed adequate power (>90%), the sample sizes in the secondary analysis were underpowered (<80%). In addition, postoperative pharmacotherapy exposure was not examined which could influence clinical outcomes. Given the limitations of using claims to infer exposure, the efficacy of pharmacotherapy to reduce postoperative complications remains unclear, and future research is warranted. Various supplements (eg, calcium and vitamin D) were excluded from the criteria used to define osteoporosis pharmacotherapy. As these medications are available over the counter, more included patients with a prior fragility fracture could have been treated with such pharmacotherapy before THA. Another limitation is that, although propensity score matching and multivariable regression were used, other confounders could have influenced the results. Although rates of certain comorbidities remained significantly different at baseline, double adjustment via multivariable logistic regression was used to limit potential confounding effects when evaluating prior fragility fractures as an independent risk factor. Finally, as is a limitation of many database studies, BMI data were not universally available for all included patients, and therefore, our adjustment for BMI was incomplete.

Further research investigating optimal perioperative management strategies and intraoperative implant type and fixation techniques for THA candidates with osteoporosis is warranted. This population of patients has an increased risk profile that, with recognition and appropriate screening, can be mitigated with surgical techniques and perioperative care during THA.

Conclusions

Fragility fractures within 3 years before THA are associated with significantly increased risk of periprosthetic fracture, all-cause revision, and secondary fragility fractures postoperatively. Surgeons should recognize this increased risk even in the absence of a formal osteoporosis diagnosis. Among patients with a history of fragility fracture, starting osteoporosis pharmacotherapy within 3 years before THA may not significantly mitigate the risk of these postoperative complications.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: O. C. Lee is an AAOS delegate to the Board of the United States Bone and Joint Initiative and US Subcommittee Chair of the Fragility Fracture Network. G. N. Guild is a paid consultant for and received reserach support from Smith & Nephew; has stock or stock options in Total Joint Orthopaedics; is a member in the AAHKS Education Committee. W. F. Sherman is a critical evaluator for AAOS and is in the Knee Program Committee of AAOS.

Footnotes

Appendix

Supplemental Table 1.

| Description | Code(s) |

|---|---|

| THA | CPT-27130 |

| Fragility fracture diagnosis codes | |

| Hip | ICD-9-D-82000:ICD-9-D-82009, ICD-9-D-82020:ICD-9-D-82022, ICD-9-D-8208, ICD-9-D-73314, ICD-10-D-S72001A, ICD-10-D-S72002A, ICD-10-D-S72009A, ICD-10-D-S72011A, ICD-10-D-S72012A, ICD-10-D-S72019A, ICD-10-D-S72021A, ICD-10-D-S72022A, ICD-10-D-S72023A, ICD-10-D-S72031A, ICD-10-D-S72032A, ICD-10-D-S72033A, ICD-10-D-S72041A, ICD-10-D-S72042A, ICD-10-D-S72043A, ICD-10-D-S72091A, ICD-10-D-S72092A, ICD-10-D-S72099A, ICD-10-D-S72101A, ICD-10-D-S72102A, ICD-10-D-S72109A, ICD-10-D-S72141A, ICD-10-D-S72142A, ICD-10-D-S72143A, ICD-10-D-S72231A, ICD-10-D-S72232A, ICD-10-D-S7223XA, ICD-10-D-M84451A, ICD-10-D-M84452A, ICD-10-D-M84453A, ICD-10-D-M84459A, ICD-9-D-73314, ICD-10-D-M80051A, ICD-10-D-M80052A, ICD-10-D-M80059A, ICD-10-D-M80851A, ICD-10-D-M80852A, ICD-10-D-M80859A |

| Spine | ICD-9-D-80500, ICD-9-D-80501, ICD-9-D-80502, ICD-9-D-80503, ICD-9-D-80504, ICD-9-D-80505, ICD-9-D-80506, ICD-9-D-80507, ICD-9-D-8052, ICD-9-D-8054, ICD-9-D-8058, ICD-9-D-8060, ICD-9-D-80600:ICD-9-D-80609, ICD-9-D-80620:ICD-9-D-80629, ICD-9-D-8064, ICD-9-D-8068, ICD-9-D-73313, ICD-10-D-S129XXA, ICD-10-D-S12000A, ICD-10-D-S12001A, ICD-10-D-S12100A, ICD-10-D-S12101A, ICD-10-D-S12200A, ICD-10-D-S12201A, ICD-10-D-S12300A, ICD-10-D-S12301A, ICD-10-D-S12400A, ICD-10-D-S12401A, ICD-10-D-S12500A, ICD-10-D-S12501A, ICD-10-D-S12600A, ICD-10-D-S12601A, ICD-10-D-S22009A, ICD-10-D-S32009A, ICD-10-D-S3210XA, ICD-10-D-S322XXA, ICD-10-D-S14101A, ICD-10-D-S14102A, ICD-10-D-S14103A, ICD-10-D-S14104A, ICD-10-D-S14111A, ICD-10-D-S14112A, ICD-10-D-S14113A, ICD-10-D-S14114A, ICD-10-D-S14121A, ICD-10-D-S14122A, ICD-10-D-S14123A, ICD-10-D-S14124A, ICD-10-D-S14131A, ICD-10-D-S14132A, ICD-10-D-S14133A, ICD-10-D-S14134A, ICD-10-D-S14151A, ICD-10-D-S14152A, ICD-10-D-S14153A, ICD-10-D-S14154A, ICD-10-D-S14105A, ICD-10-D-S14106A, ICD-10-D-S14107A, ICD-10-D-S14115A, ICD-10-D-S14116A, ICD-10-D-S14117A, ICD-10-D-S14125A, ICD-10-D-S14126A, ICD-10-D-S14127A, ICD-10-D-S14135A, ICD-10-D-S14136A, ICD-10-D-S14137A, ICD-10-D-S14155A, ICD-10-D-S14156A, ICD-10-D-S14157A, ICD-10-D-S24101A, ICD-10-D-S24102A, ICD-10-D-S24111A, ICD-10-D-S24112A, ICD-10-D-S24131A, ICD-10-D-S24132A, ICD-10-D-S24151A, ICD-10-D-S24152A, ICD-10-D-S24103A, ICD-10-D-S24104A, ICD-10-D-S24113A, ICD-10-D-S24114A, ICD-10-D-S24133A, ICD-10-D-S24134A, ICD-10-D-S24153A, ICD-10-D-S24154A, ICD-10-D-S34109A, ICD-10-D-S34119A, ICD-10-D-S34129A, ICD-10-D-S32009A, ICD-10-D-S34101A, ICD-10-D-S34111A, ICD-10-D-S34121A, ICD-10-D-S32019A, ICD-10-D-S34102A, ICD-10-D-S34112A, ICD-10-D-S34122A, ICD-10-D-S32029A, ICD-10-D-S34103A, ICD-10-D-S34113A, ICD-10-D-S34123A, ICD-10-D-S32039A, ICD-10-D-S34104A, ICD-10-D-S34114A, ICD-10-D-S34124A, ICD-10-D-S32049A, ICD-10-D-S34105A, ICD-10-D-S34115A, ICD-10-D-S34125A, ICD-10-D-S32059A, ICD-10-D-S14109A, ICD-10-D-S24109A, ICD-10-D-S34109A, ICD-10-D-S34139A, ICD-10-D-M4850XA, ICD-10-D-M8008XA, ICD-10-D-M8448XA, ICD-10-D-M8468XA, ICD-9-D-73313, ICD-9-D-73315, ICD-10-D-M8008XA, ICD-10-D-M8088XA |

| Pelvis | ICD-9-D-8080, ICD-9-D-8082, ICD-9-D-80841, ICD-9-D-80842, ICD-9-D-80849, ICD-9-D-8088, ICD-10-D-S32401A, ICD-10-D-S32402A, ICD-10-D-S32409A, ICD-10-D-S32501A, ICD-10-D-S32502A, ICD-10-D-S32501A, ICD-10-D-S32502A, ICD-10-D-S32509A, ICD-10-D-S32301A, ICD-10-D-S32302A, ICD-10-D-S32309A, ICD-10-D-S32601A, ICD-10-D-S32602A, ICD-10-D-S32609A, ICD-10-D-S32810A, ICD-10-D-S32811A, ICD-10-D-S3282XA, ICD-10-D-S3289XA, ICD-10-D-S329XXA, ICD-10-D-M84454A |

| Wrist | ICD-9-D-81340:ICD-9-D-81347, ICD-9-D-73312, ICD-10-D-S5290XA, ICD-10-D-S52531A, ICD-10-D-S52532A, ICD-10-D-S52539A, ICD-10-D-S52541A, ICD-10-D-S52542A, ICD-10-D-S52549A, ICD-10-D-S52501A, ICD-10-D-S52502A, ICD-10-D-S52509A, ICD-10-D-S52601A, ICD-10-D-S52602A, ICD-10-D-S52609A, ICD-10-D-S52111A, ICD-10-D-S52112A, ICD-10-D-S52119A, ICD-10-D-S52521A, ICD-10-D-S52522A, ICD-10-D-S52529A, ICD-10-D-S52011A, ICD-10-D-S52012A, ICD-10-D-S52019A, ICD-10-D-S52621A, ICD-10-D-S52622A, ICD-10-D-S52629A, ICD-10-D-S52011A, ICD-10-D-S52012A, ICD-10-D-S52019A, ICD-10-D-S52621A, ICD-10-D-A52622A, ICD-10-D-S52629A, ICD-10-D-M84431A, ICD-10-D-M84432A, ICD-10-D-M84439A, ICD-9-D-73312, ICD-10-D-M80031A, ICD-10-D-M80032A, ICD-10-D-M80039A, ICD-10-D-M80831A, ICD-10-D-M80832A, ICD-10-D-M80839A |

| Humerus | ICD-9-D-81200:ICD-9-D-81209, ICD-9-D-81220, ICD-9-D-81221, ICD-9-D-81240:ICD-9-D-81249, ICD-9-D-73311, ICD-10-D-S42201A, ICD-10-D-S42202A, ICD-10-D-S42209A, ICD-10-D-S42211A, ICD-10-D-S42212A, ICD-10-D-S42213A, ICD-10-D-S42214A, ICD-10-D-S42215A, ICD-10-D-S42216A, ICD-10-D-S42291A, ICD-10-D-S42292A, ICD-10-D-S42293A, ICD-10-D-S42294A, ICD-10-D-S42295A, ICD-10-D-S42296A, ICD-10-D-S42251A, ICD-10-D-S42252A, ICD-10-D-S42253A, ICD-10-D-S42254A, ICD-10-D-S42255A, ICD-10-D-S42256A, ICD-10-D-S42291A, ICD-10-D-S42292A, ICD-10-D-S42293A, ICD-10-D-S42294A, ICD-10-D-S42295A, ICD-10-D-S42296A, ICD-10-D-S42301A, ICD-10-D-S42302A, ICD-10-D-S42309A, ICD-10-D-S42391A, ICD-10-D-S42392A, ICD-10-D-S42399A, ICD-10-D-S42401A, ICD-10-D-S42402A, ICD-10-D-S42409A, ICD-10-D-S42411A, ICD-10-D-S42412A, ICD-10-D-S42413A, ICD-10-D-S42414A, ICD-10-D-S42415,A ICD-10-D-S42416A, ICD-10-D-S42431A, ICD-10-D-S42432A, ICD-10-D-S42433A, ICD-10-D-S42434A, ICD-10-D-S42435A, ICD-10-D-S42436A, ICD-10-D-S42451A, ICD-10-D-S42452A, ICD-10-D-S42453A, ICD-10-D-S42454A, ICD-10-D-S42455A, ICD-10-D-S42456A, ICD-10-D-S42441A, ICD-10-D-S42442A, ICD-10-D-S42443A, ICD-10-D-S42444A, ICD-10-D-S42445A, ICD-10-D-S42446A, ICD-10-D-S42461A, ICD-10-D-S42462A, ICD-10-D-S42463A, ICD-10-D-S42464A, ICD-10-D-S42465A, ICD-10-D-S42466A, ICD-10-D-S42471A, ICD-10-D-S42472A, ICD-10-D-S42473A, ICD-10-D-S42474A, ICD-10-D-S42475A, ICD-10-D-S42476A, ICD-10-D-S42491A, ICD-10-D-S42492A, ICD-10-D-S42493A, ICD-10-D-S42494A, ICD-10-D-S42495A, ICD-10-D-S42496A, ICD-10-D-M84421A, ICD-10-D-M84422A, ICD-10-D-M84429A, ICD-9-D-73311, ICD-10-D-M80011A, ICD-10-D-M80012A, ICD-10-D-M80019A, ICD-10-D-M80021A, ICD-10-D-M80022A, ICD-10-D-M80029A, ICD-10-D-M80811A, ICD-10-D-M80812A, ICD-10-D-M80819A, ICD-10-D-M80821A, ICD-10-D-M80822A, ICD-10-D-M80829A |

| Other | ICD-9-D-73310, ICD-9-D-73316, ICD-9-D-73319, ICD-10-D-M8000XA, ICD-10-D-M80041A, ICD-10-D-M80042A, ICD-10-D-M80049A, ICD-10-D-M80061A, ICD-10-D-M80062A, ICD-10-D-M80069A, ICD-10-D-M80071A, ICD-10-D-M80072A, ICD-10-D-M80079A, ICD-10-D-M8080XA, ICD-10-D-M80841A, ICD-10-D-M80842A, ICD-10-D-M80849A, ICD-10-D-M80861A, ICD-10-D-M80862A, ICD-10-D-M80869A, ICD-10-D-M80871A, ICD-10-D-M80872A, ICD-10-D-M80879A |

| Exclusion criteria | |

| Traumatic fractures | ICD-9-D-E800:ICD-9-D-E848, ICD-9-D-E916:ICD-9-D-E919, ICD-9-D-E9288, ICD-9-D-E9289, ICD-9-D-E9290, ICD-9-D-E9291, ICD-9-D-E957:ICD-9-D-E959, ICD-9-D-E960:ICD-9-D-E966, ICD-9-D-E968:ICD-9-D-E979, ICD-9-D-E987:ICD-9-D-E989, ICD-9-D-E999, ICD-10-D-V00:ICD-10-D-V99, ICD-10-D-W09:ICD-10-D-W17, ICD-10-D-X34:ICD-10-D-X39, ICD-10-D-X79:ICD-10-D-X83, ICD-10-D-Y00:ICD-10-D-Y04, ICD-10-D-Y08:ICD-10-D-Y09, ICD-10-D-Y29:ICD-10-D-Y38 |

| Prior revision THA | CPT-27134, CPT-27137, CPT-27138 |

| Active hip infection | ICD-9-D-73005, ICD-9-D-73015, ICD-9-D-73025, ICD-9-D-73035, ICD-9-D-71105, ICD-9-D-6143, ICD-9-D-6144, ICD-10-D-M86051, ICD-10-D-M86052, ICD-10-D-M86059, ICD-10-D-M8608, ICD-10-D-M86151, ICD-10-D-M86152, ICD-10-D-M86159, ICD-10-D-M8618, ICD-10-D-M86251, ICD-10-D-M86252, ICD-10-D-M86259, ICD-10-D-M8628, ICD-10-D-M86351, ICD-10-D-M86352, ICD-10-D-M86359, ICD-10-D-M8638, ICD-10-D-M86451, ICD-10-D-M86452, ICD-10-D-M86459, ICD-10-D-M8648, ICD-10-D-M86551, ICD-10-D-M86552, ICD-10-D-M86559, ICD-10-D-M8658, ICD-10-D-M009 |

| Primary hip surgeries during follow-up | CPT-27130, CPT-27125, CPT-27132, CPT-27265, CPT-27266, CPT-27245, CPT-27244, CPT-27120 |

| Achalasia | ICD-9-D-5300, ICD-10-D-K220 |

| Multiple myeloma | ICD-9-D-20300, ICD-9-D-20301, ICD-9-D-20302, ICD-10-D-C9002, ICD-10-D-C9001, ICD-10-D-C9000 |

| Paget’s disease | ICD-9-D-7310, ICD-9-D-7311, ICD-10-D-M880, ICD-10-D-M881, ICD-10-D-M88811, ICD-10-D-M88812, ICD-10-D-M88819, ICD-10-D-M88821, ICD-10-D-M88822, ICD-10-D-M88829, ICD-10-D-M88831, ICD-10-D-M88832, ICD-10-D-M88839, ICD-10-D-M88841, ICD-10-D-M88849, ICD-10-D-M88851, ICD-10-D-M88852, ICD-10-D-M88859, ICD-10-D-M88861, ICD-10-D-M88862, ICD-10-D-M88869, ICD-10-D-M88871, ICD-10-D-M88872, ICD-10-D-M8888, ICD-10-D-M8889, ICD-10-D-M889, ICD-10-D-M9060, ICD-10-D-M90621, ICD-10-D-M90641, ICD-10-D-M90651, ICD-10-D-M90652, ICD-10-D-M90661, ICD-10-D-M90671, ICD-10-D-M90672, ICD-10-D-M9068, ICD-10-D-M9069 |

| Hyperparathyroidism | ICD-9-D-25200, ICD-9-D-25201, ICD-9-D-25202, ICD-9-D-25208, ICD-9-D-58881, ICD-10-D-E210, ICD-10-D-E211, ICD-10-D-E212, ICD-10-D-E213, ICD-10-D-N2581 |

| Drug allergy | ICD-9-D-V148, ICD-10-D-Z888 |

| Hyperthyroidism | ICD-9-D-24290, ICD-9-D-24200, ICD-10-D-E0590, ICD-10-D-E0500, ICD-10-D-E0520, ICD-10-D-E0591 |

| Metastatic cancer | ICD-9-D-1960:ICD-9-D-1999, ICD-10-D-C770:ICD-10-D-C809 |

| Esophageal varices | ICD-9-D-4560, ICD-9-D-4561, ICD-10-D-I8500, ICD-10-D-I8501 |

| Esophageal stricture | ICD-9-D-5303, ICD-10-D-Q393 |

| Barrett esophagus | ICD-9-D-53085, ICD-10-D-K2270, ICD-10-D-K22710, ICD-10-D-K22711, ICD-10-D-K22719 |

| Roux-en-Y Bypass | CPT-43621, CPT-43633, CPT-43644 |

| Cachexia | ICD-9-D-7994, ICD-10-D-R64 |

| Other | |

| Osteoporosis | ICD-10-D-M810, ICD-10-D-M818, ICD-9-D-73300, ICD-9-D-73301, ICD-9-D-73309, ICD-9-D-73302, ICD-9-D-73303 |

| Vitamin D deficiency | ICD-9-D-2689, ICD-10-D-E559 |

| Pharmacotherapy | |

| Alendronate | GENERIC_DRUG-ALENDRONATE_SODIUM GENERIC_DRUG-ALENDRONATE_SODIUM/VITAMIN_D3 |

| Risedronate | GENERIC_DRUG-RISEDRONATE_SOD/CALCIUM_CARB GENERIC_DRUG-RISEDRONATE_SODIUM |

| Ibandronate | GENERIC_DRUG-IBANDRONATE_SODIUM |

| Zoledronic acid | GENERIC_DRUG-ZOLEDRONIC_AC/MANNITOL/0.9NACL GENERIC_DRUG-ZOLEDRONIC_ACID GENERIC_DRUG-ZOLEDRONIC_ACID/MANNITOL&WATER GENERIC_DRUG-ZOLEDRONIC_ACID/MANNITOL-WATER |

| Raloxifene | GENERIC_DRUG-RALOXIFENE_HCL |

| Denosumab | GENERIC_DRUG-DENOSUMAB |

| Teriparatide | GENERIC_DRUG-TERIPARATIDE |

| Abaloparatide | GENERIC_DRUG-ABALOPARATIDE |

| Calcitonin | GENERIC_DRUG-CALCITONIN_SALMON_SYNTHETIC |

Supplemental Table 2.

| Complication | Code(s) |

|---|---|

| Periprosthetic fracture | ICD-9-D-99644, ICD-10-D-M9701XA, ICD-10-D-M9702XA, ICD-10-D-T84040A, ICD-10-D-T84041A |

| Fragility fractures | See Supplemental Table 1 |

| Revision THA | CPT-27134, CPT-27137, CPT-27138 |

Supplemental Table 3.

| Medications | Patients | Claims | Average RX length (d) | Average RX CoPay |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 303 | 1836 | 46 | $21.85 |

| ALENDRONATE_SODIUM | 196 | 1136 | 46.39 | $5.45 |

| CALCITONIN_SALMON_SYNTHETIC | 29 | 164 | 35.23 | $14.71 |

| DENOSUMAB | 16 | 25 | 78.08 | $52.84 |

| IBANDRONATE_SODIUM | 46 | 167 | 54.4 | $35.75 |

| RALOXIFENE_HCL | 15 | 84 | 41.79 | $24.33 |

| RISEDRONATE_SODIUM | 20 | 112 | 56.18 | $65.87 |

| TERIPARATIDE | 21 | 146 | 32 | $101.41 |

| ZOLEDRONIC_ACID/MANNITOL-WATER | −1a | −1a | 227.5 | $0.00 |

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Wright N.C., Looker A.C., Saag K.G. The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(11):2520. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armas L.A., Recker R.R. Pathophysiology of osteoporosis: new mechanistic insights. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2012;41(3):475. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lane N.E. Epidemiology, etiology, and diagnosis of osteoporosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(2 Suppl):S3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sözen T., Özışık L., Başaran N. An overview and management of osteoporosis. Eur J Rheumatol. 2017;4(1):46. doi: 10.5152/eurjrheum.2016.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.United States Bone and Joint Initiative: The Burden of Musculoskeletal Diseases in the United States (BMUS), Fourth Edition, 2020. Rosemont, IL. http://www.boneandjointburden.org Available at.

- 6.Cummings S.R., Melton L.J. Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet. 2002;359(9319):1761. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08657-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones L., Singh S., Edwards C., Goyal N., Singh I. Prevalence of vertebral fractures in CTPA's in adults aged 75 and older and their association with subsequent fractures and mortality. Geriatrics (Basel) 2020;5(3) doi: 10.3390/geriatrics5030056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerdhem P. Osteoporosis and fragility fractures: vertebral fractures. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27(6):743. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dang D.Y., Zetumer S., Zhang A.L. Recurrent fragility fractures: a cross-sectional analysis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019;27(2):e85. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-17-00103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dennison E., Mohamed M.A., Cooper C. Epidemiology of osteoporosis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2006;32(4):617. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman S.M., Mendelson D.A. Epidemiology of fragility fractures. Clin Geriatr Med. 2014;30(2):175. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burge R., Dawson-Hughes B., Solomon D.H., Wong J.B., King A., Tosteson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005-2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(3):465. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dyer S.M., Crotty M., Fairhall N. A critical review of the long-term disability outcomes following hip fracture. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):158. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0332-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang H.X., Majumdar S.R., Dick D.A. Development and initial validation of a risk score for predicting in-hospital and 1-year mortality in patients with hip fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(3):494. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanis J.A., Johnell O., De Laet C. A meta-analysis of previous fracture and subsequent fracture risk. Bone. 2004;35(2):375. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Capone A., Congia S., Civinini R., Marongiu G. Periprosthetic fractures: epidemiology and current treatment. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2017;14(2):189. doi: 10.11138/ccmbm/2017.14.1.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan T., Middleton R., Alvand A., Manktelow A.R.J., Scammell B.E., Ollivere B.J. High mortality following revision hip arthroplasty for periprosthetic femoral fracture. Bone Joint J. 2020;102-b(12):1670. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.102B12.BJJ-2020-0367.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haughom B.D., Basques B.A., Hellman M.D., Brown N.M., Della Valle C.J., Levine B.R. Do mortality and complication rates differ between periprosthetic and native hip fractures? J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(6):1914. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cram P., Landon B.E., Matelski J. Utilization and short-term outcomes of primary total hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States and Canada: an analysis of New York and Ontario administrative data. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(4):547. doi: 10.1002/art.40407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karachalios T.S., Koutalos A.A., Komnos G.A. Total hip arthroplasty in patients with osteoporosis. Hip Int. 2020;30(4):370. doi: 10.1177/1120700019883244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ha C.W., Park Y.B. Underestimation and undertreatment of osteoporosis in patients awaiting primary total knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2020;140(8):1109. doi: 10.1007/s00402-020-03462-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson A.J., Desai S., Zhang C. A calcar collar is protective against early torsional/spiral periprosthetic femoral fracture: a paired cadaveric biomechanical analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102(16):1427. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.19.01125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waligora ACt, Owen J.R., Wayne J.S., Hess S.R., Golladay G.J., Jiranek W.A. The effect of prophylactic cerclage wires in primary total hip arthroplasty: a biomechanical study. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(6):2023. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh I., Duric D., Motoc A., Edwards C., Anwar A. Relationship of prevalent fragility fracture in dementia patients: three years follow up study. Geriatrics (Basel) 2020;5(4) doi: 10.3390/geriatrics5040099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bunta A.D., Edwards B.J., Macaulay W.B., Jr. Own the bone, a system-based intervention, improves osteoporosis care after fragility fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(24):e109. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.01494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Services USDoHaH 2019 Medicare fee-for service supplemental improper payment data. 2019. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Monitoring-Programs/Medicare-FFS-Compliance-Programs/CERT/Downloads/2017-Medicare-FFS-Improper-Payment.pdf

- 27.Cooper C., Atkinson E.J., O'Fallon W.M., Melton L.J., 3rd Incidence of clinically diagnosed vertebral fractures: a population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota, 1985-1989. J Bone Miner Res. 1992;7(2):221. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650070214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.