Abstract

Yield loss due to noxious weeds is one among several reasons for the reduced economy for the developing countries. Impacts of one such weed i.e. Mikania micrantha were investigated on the rate of seed germination, growth, biomass, photosynthetic pigments, total soluble protein, phenolics and proline content of leaves of Macrotylama uniflorum (an important pulse). In a completely randomized setup, control and four concentrations (10 mg/ml, 50 mg/ml, 100 mg/ml and 200 mg/ml) of the aqueous leaf extracts of M. micrantha were tested on the seeds of M. uniflorum. The extracts inhibited germination, growth, biomass, chlorophyll, carotenoid and protein contents. The protein content of M. uniflorum decreased to 8.48 mg/g at 200 mg/ml. Similarly, shoot length and root length were also decreased up to 5.11 cm and 0.85 cm respectively and water content increased with the increasing concentration of weed extracts. The leaf extracts resulted in an increase in the phenolics (19.66 mg) and proline (24.49 mg) content of the crop plant. The preliminary study indicated that the aqueous leaf extracts of weed plant resulted in negative or detrimental impact on growth and physiology of the plant and this might be due to the release of secondary metabolites. The present investigation may further lead to the identification of certain secondary metabolites or allelo-chemicals that may have an important agricultural application for sustainability and may enhance the level of crop protection against several other harmful plant species.

Keywords: Allelopathy, Mikania micrantha, Macrotylama uniflorum, Phenolics, Proline, Secondary metabolites

Highlights

-

•

Allelopathic impacts of Mikania micrantha Kunth were investigated on the rate of seed germination, growth, biomass, photosynthetic pigments, total soluble protein, phenolics and proline content of Macrotylama uniflorum (Lam.) Verdc.

-

•

The extracts inhibited germination, growth, biomass, chlorophyll, carotenoid and protein contents. The protein content of M. uniflorum decreased to 8.48 mg/g at 200 mg/ml. Similarly shoot length, root length also decreased up to 5.11 cm, 0.85 cm respectively and water content increased with increasing concentration of weed extracts.

-

•

The leaf extracts resulted in an increase in the phenolics (19.66 mg) and proline (24.49 mg) content of the crop plant. The aqueous extracts of leaves caused detrimental impact on growth and physiology of the crop plant and this might be due to release of secondary metabolites.

-

•

This present investigation may further lead to identification of certain secondary metabolites or allelo-chemicals for agricultural application and might enhance the level of crop protection against several other harmful plant species.

Allelopathy; Mikania micrantha; Macrotylama uniflorum; Phenolics; Proline; Secondary metabolites

1. Introduction

A biological phenomenon by virtue of which an organism produces biochemical substances which influence the morphology and physiology of another organism is referred to as allelopathy (Cheng and Cheng, 2015). Root exudation, leaching, deposition of leaf particles and volatilization are the process involved in transport of the chemicals from one plant to another (Liza and Ram, 2017). The biochemicals or allelo-chemicals are secondary metabolites which are not required for growth, development and reproduction (Stamp, 2003; Langenheim, 1994). They could have detrimental effects on the target organisms. Allelo-chemicals are an important part of defense mechanisms in plants such as herbivory, microbial attack etc. (Stamp, 2003; Fraenkel, 1981).

Macrotyloma uniflorum belongs to family Fabaceae or leguminosae. It is a short day, twining, succulent and annual climbing herb. M. uniflorum has excellent nutritional as well as ethnomedicinal properties (Kumar, 2006; Singh, 1991; Ranasinghe and ERHSS, 2017). It has various properties like anti-obesity, anti-diabetic, antioxidant etc. (Kaundal et al., 2019). It is a rich source of vitamins, proteins and minerals used in developing countries to meet nutritional requirements.

Mikania micrantha is an invasive species which is responsible to alter the morphology and physiology of indigenous crop plants (Stamp, 2003; Matawali et al., 2016a, Matawali et al., 2016b). Mikania micrantha (weed plant) is known to grow in such a way that other plant growth and activities are retarded. It is known to release substances that hamper the growth and development of other plant species (Tiwari et al., 2005). In this way, the weed plants deteriorate young plantations as well as nurseries which have become a threat to today's sustainable agriculture system. In the current study, for exploring the allelopathic potential of M. micrantha, aqueous leaf extracts were used against an important ethnomedicinal pulse Macrotyloma uniflorum. The biochemical changes of the crop plant (Macrotyloma uniflorum) were recorded to verify the negative impact of Mikania micrantha. Allelopathic impacts may be studied further as an important mechanism to know the chemicals or metabolites involved and also may be utilized to inhibit some unwanted growth of plant species. This approach may further lead to sustainable agriculture and crop protection.

1.1. Study of different weeds on plant system

| Allelopathic plant | Effect on different plant systems |

|---|---|

| Black walnut | reduced corn yield |

| Leucaena | reduced the yield of wheat and turmeric |

| Lantana | germination and growth of milkweed vine |

| Sour orange | inhibited seed germination and root growth of pigweed, bermudagrass, and lambsquarters |

| Red maple, swamp chestnut oak, sweet bay, and red cedar | inhibited lettuce seed |

| Chaste tree or box elder | retarded the growth of pangolagrass, a pasture grass |

2. Materials and methods

The experiments were conducted to study the potential allelopathic effects of M. micrantha on M. uniflorum.

2.1. Collection of plant materials

The weed Mikania micrantha were collected from Centurion University of Technology and Management (CUTM), Jatni campus, Odisha, India (Sahoo and Mahalik, 2020). The high quality and viable seeds of Macrotyloma uniflorum were collected from the Plant Breeding and Genetics department, Orissa University of Agriculture and Technology (OUAT), Odisha (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Seeds of Macrotylama uniflorum.

2.2. Preparation of aqueous extracts of plant material

Plant leaves were separated from the shoots and were shade dried until removal of moisture. Samples were crushed to powdered form and stored in the airtight glass jars until further use. Sample solutions of varied concentrations with increasing order (10, 50, 100 and 200 mg/ml) were prepared and stored at 4ᵒC in a refrigerator and used within 24–48 h to treat the M. uniflorum seeds.

2.3. Seed germination assay and screening

Healthy and fresh seeds of M. uniflorum were kept on moist filter paper soaked with different concentrations of M. micrantha aqueous extracts. Controls were treated with 20 ml of distilled water (Bhatt et al., 2016; Mittra et al., 2004). The seeds were kept under dark for four days in a controlled room temperature. The germination was considered when the radicals were ~ 2 mm or more in length. The radical length was measured after 4 days of germination. The seedling vigour index (Abdul-Baki and Anderson, 1973), plant tolerance index (Turner and Marshall, 1972) and phytotoxicity percent (Chou and Lin, 1976) were calculated as follows:

| SVI = Germination percentage x Radical length |

| PTI = Radical length of the treatment/ radical length of control x 100 |

| Phytotoxicity percent = Root length of control-root length of treatment x 100 |

2.4. Water content and biomass

Biomass was determined after 14 days of treatment with aqueous extracts of Mikania micrantha by taking the single whole plant (Macrotyloma uniflorum) including shoots and roots. The seedlings were taken and properly washed with distilled water, dried using blotting paper and later the fresh weights were recorded. The samples were dried at 60 °C for 2–3 days in an oven and later the dry weights (DW) were measured (Kim et al., 2005).

2.5. Photosynthetic pigments

500 mg fresh and healthy leaves were properly homogenized in 80% chilled acetone. The homogenized samples were then centrifuged for 10 min at 4ᵒC, 10,000 rpm in the dark. Supernatant was taken and the absorbances were recorded (Arnon, 1949).

2.6. Total leaf protein

The soluble proteins were extracted using Acetone-TCA method (Parida et al., 2002; Lowry et al., 1951). After the extraction, samples were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 20 min and the supernatant was collected. Sample (0.2 ml) was taken to which 1 ml de-ionized water was added. Further alkaline Copper (5 ml) solution was added and kept for 10 min. Folin-Ciocalteau reagent (0.5 ml) was added and then incubated for 30 min in the dark. Later the absorbance at 660 nm was recorded.

2.7. Total phenolics

Sample extraction was carried out using 80% ethanol and estimated using Folin – Ciocalteau reagent (Parida et al., 2002; Mallik and Singh, 1980). 0.5 g leaf samples were homogenized with 80% ethanol. The homogenates were centrifuged for 20 min at 10,000 rpm. Residues were re-extracted several times with 80% ethanol by centrifugation. The supernatant collected was evaporated and the residues after evaporation were dissolved with distilled water (5 ml). 2 ml sample was taken and the volume was made up to 3ml, by distilled water. 0.5 ml Folin-Ciocalteau reagent and 20% Sodium Carbonate (2 ml) solution was further added. The reagents were mixed properly and kept in boiling water bath for 1 min. The mixture was then cooled to room temperature and absorbance at 650 nm was recorded.

2.8. Proline

0.5g fresh leaves were taken and properly homogenized using 3% sulfosalicylic acid. The homogenates were filtered through filter paper. 2 ml each of the filtrate, ninhydrin and glacial acetic acid was mixed altogether and incubated at 100 °C for 1 h (Bates et al., 1973). The reaction was later stopped by keeping test tubes in an ice bucket. Toluene (2 ml) was added and the mixture was vigorously shaken for a few seconds. The separated aqueous layer of toluene was warmed at room temperature; the colored sample was measured at 520nm wavelength.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Data represented through mean along with the standard deviation calculated from five number of replicates and three experiments consecutively. DMRT was used as a post hoc test after running ANOVA to analyze and compare the allelopathic effect of M. micrantha on M. uniflorum at p < 0.05 (5% significance level).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Seed germination assay and plant growth

The rate of germination of M. uniflorum seeds responded differently manner to different concentrations of M. micrantha aqueous extracts. Germination rate decreased with increasing concentration of M. micrantha extracts and the detrimental effect was more pronounced at 200 mg/ml concentration (Table 1). The germination percentage was observed to be 85.55% (control), 83.75% (10 mg), 76.25% (50 mg), 50.78% (100 mg) and 30.44% (200 mg). The radical length decreased with increasing aqueous extract concentrations of M. micrantha that accounted for 4.12 cm and 1.26 cm for 10 mg and 200 mg respectively (Table 1). The seedling vigor index of M. uniflorum was found to be 343.37 and 38.55 in 10 mg and 200 mg treatment respectively. Plant tolerance index was observed to show a decreasing trend from 10 mg to 200 mg aqueous extracts of M. micrantha. Tolerance to M. micrantha decreased when treatment reached to 200 mg amounting to 29.68.

Table 1.

Germination percentage, Radical length, Seedling vigour index (SVI), Plant tolerance index (PTI) and Phytotoxicity percentage of M. uniflorum.

| Sample | M. micrantha extracts (mg/ml) | Germination (%) | Radical length (cm) | SVI | PTI | % Phytotoxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. uniflorum | 0 | 85.55 ± 0.74a | 4.26 ± 0.65a | 373.54 | 100 | 0 |

| 10 | 83.75 ± 0.94a | 4.12 ± 0.61a | 343.37 | 96.09 | 166 | |

| 50 | 76.25 ± 1.69b | 2.61 ± 0.33b | 198.25 | 60.93 | 258 | |

| 100 | 50.78 ± 1.69c | 1.76 ± 0.12c | 89.71 | 41.41 | 283 | |

| 200 | 30.44 ± 0.94d | 1.26 ± 0.21c | 38.55 | 29.68 | 329 |

∗Values represent mean ± SD, letters represent significant differences among treatments at 5% level of significance (P ≤ 0.05) as per the DMRT analysis.

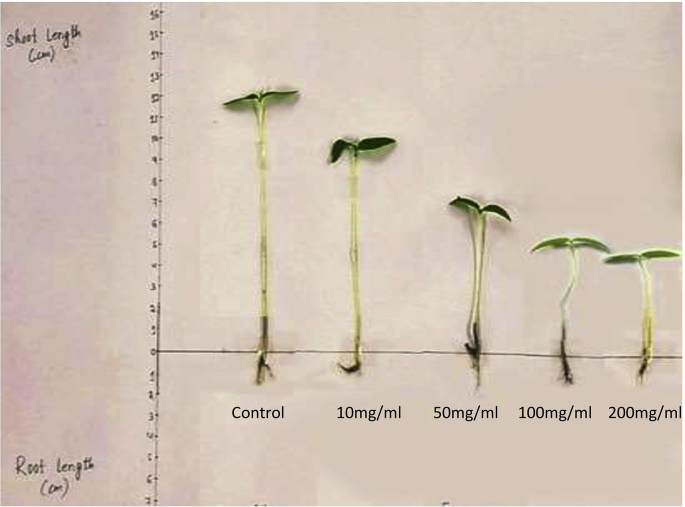

3.2. Effect of M. micrantha on growth of M. uniflorum

M. micrantha extracts in the experimental conditions a showed significant amount of growth reduction in M. uniflorum. Growth of shoots were affected significantly at 200 mg (5.11 cm), 100 mg (5.67 cm), 50 mg (6.43 cm) and 10 mg (9.59 cm) as compared to control (12.61 cm) (Table 2, Figure 2). Root length indicated growth reduction in all the samples i.e. 2.48 cm, 1.56 cm, 1.31 cm and 0.85 cm at 10 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg and 200 mg respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of M. micrantha on growth of M. uniflorum.

| Treatments (mg/ml) | Shoot length (cm) | Root length (cm) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 12.61 ± 0.16a | 4.14 ± 0.24a |

| 10 | 9.59 ± 0.12b | 2.48 ± 0.19b |

| 50 | 6.43 ± 0.19c | 1.56 ± 0.01c |

| 100 200 |

5.67 ± 0.21d 5.11 ± 0.13d |

1.31 ± 0.21c 0.85 ± 0.07d |

∗Values represent mean ± SD, letters represent significant differences among treatments at 5% level of significance (P ≤ 0.05) as per the DMRT analysis.

Figure 2.

Shoot and Root length of M. uniflorum exposed to different concentrations of M. micrantha plant extracts.

Abiotic stress is known to be highly toxic and have severe deleterious impacts on the growth of the plant (Rubio et al., 1994; Watanabe and Suzuki, 2002; Maksymiec and Krupa, 2006). In the growth medium it is observed to be having significant shoot and root length reduction (Dong et al., 2005) (Figure 3). The most noticeable symptoms of abiotic toxicity were found to be the stunted growth (Huang et al., 2000; Li and Jin, 2010; Kaur and Malhotra, 2012). Similar results regarding the effects of leaf extracts of different weeds (Parthenium hysterophorus, Tridax Procumbens and Hyptis Saveolens) on Vigna mungo germination and growth were observed (Babu et al., 2014).

Figure 3.

Morphological changes of M. uniflorum upon exposure to M. micrantha extracts.

3.3. Effect of M. micrantha on biomass of M. uniflorum

M. micrantha extracts showed significant biomass reduction in M. uniflorum plants. Biomass was significantly affected by M. micrantha treated aqueous extracts to Macrotyloma uniflorum plants i.e. 10 mg (90.56%), 50 mg (89.18%), 100 mg (90.32%) and 200 mg (94.73%) as compared to control (44.25%) plants (Table 3). Growth reduction affects biomass of the plant (Ismail and Mah., 1993; Day et al., 2016). With an increase in concentrations of the weed extracts, there was a noticeable reduction of biomass of M. uniflorum. The water content increased with increasing concentrations of aqueous extracts.

Table 3.

Effect of M. micrantha on biomass of M. uniflorum.

| Treatments (mg/ml) | Fresh Weight (g) | Dry Weight (g) | Water Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.62 ± 0.26a | 0.11 ± 0.14a | 82.25 |

| 10 | 0.53 ± 0.22b | 0.05 ± 0.11b | 90.56 |

| 50 | 0.37 ± 0.09c | 0.04 ± 0.11b | 89.18 |

| 100 200 |

0.31 ± 0.11c 0.19 ± 0.03d |

0.03 ± 0.31b 0.01 ± 0.27c |

90.32 94.73 |

∗Values represents mean ± SD, letters represent significant differences among treatments at 5% level of significance (P ≤ 0.05) as per the DMRT analysis.

3.4. Changes in concentrations of photosynthetic pigments

The quantity of pigments (Chl a, Chl b, total chlorophyll and carotenoids) under different M. micrantha aqueous extract concentrations were studied. Total Chlorophyll and carotenoid contents of M. uniflorum decreased significantly with an increase in M. micrantha levels compared to control plants (Figure 4). The Chl a, Chl b and carotenoid contents showed decreasing effects upon exposure to M. micrantha extracts. Chl a contents were recorded 234.31 μg/g and 89.07 μg/g at 10 mg/ml and 200 mg/ml respectively. Carotenoids showed 28.19 μg/g, 37.02 μg/g, 56.11 μg/g and 69.42 μg/g upon exposure to 200, 100, 50, 10 mg/ml of extracts of M. micrantha respectively whereas control carotenoid levels showed 83.13 μg/g.

Figure 4.

Photosynthetic pigments of M. uniflorum exposed to varying concentrations of M. micrantha extracts.

Extracts of M. micrantha effectively inhibit the photosynthetic pigments of M. uniflorum at various concentrations. This might be due to the release of secondary metabolites (CEN et al., 2004; Huang et al., 2012; Jyothilakshmi et al., 2015; Matawali et al., 2016a, Matawali et al., 2016b) that resulted in the reduction or inhibition of the photosynthetic activity or destruction of some chloroplasts. It was observed that Chl a, Chl b and carotenoid contents significantly decreased due to reduction in cellular Mg2+ ion concentration, which is essential for the biosynthesis of chlorophyll (Yildirim et al., 2008; Mohamed and Gomaa, 2012). Earlier it was reported that a decrease in the chlorophyll content might be due to failure in chlorophyll biosynthesis or disruption of some chloroplasts (Padmaja et al., 1990; Ahmad et al., 2007). The similar decreasing trend in the photosynthetic activity was also observed upon treatment of Amaranthus viridis extracts on Triticum aestivum (Shinde and Salve, 2019; Patel and Kumbhar, 2016).

3.5. Changes in soluble protein content

Total soluble leaf protein of M. uniflorum (obtained in mg/ml fr wt.) showed remarkable variations when treated with different extracts of this weed (Figure 5) 14.96 mg/g, 12.69 mg/g, 10.48 mg/g and 8.48 mg/g at 10, 50, 100 and 200 mg/ml respectively as compared to control plants (16.63 mg/g). The above results showed that upon exposure to stress, plants show reduced protein levels as compared to the control.

Figure 5.

Total soluble protein content, Phenolics and Proline content of M. uniflorum exposed to different concentrations of M. micrantha aqueous extracts.

The total protein contents reduced significantly as the result of exposure to M. micrantha plant extracts in M. uniflorum. The decline in protein level may be due to the disruption in translation pathway after being exposed to the allelochemicals released. This phenomenon was also observed in plants exposed to both biotic and abiotic stress (Parida et al., 2004; Jali et al., 2019).

3.6. Changes in phenolics and proline contents

Control plants showed minute phenolic content i.e. 2.79 mg/g. The phenolic contents in treated samples of M. uniflorum increased up to 8.51 mg/g, 12.35 mg/g, 15.46 mg/g and 19.66 mg/g at 10, 50, 100 and 200 mg/ml aqueous extracts respectively which is significantly higher than control (Figure 5). Enhanced phenolic metabolism produces antioxidative activity which focuses to decrease the toxic and negative effects of the stress (Zheng et al., 2011; Dai et al., 2006; Kovacsluik and Backor, 2007). Extracts of M. micrantha slow down the germination and growth of a number of plant species (Zhang et al., 2002). At least three sesquiterpenoids (secondary metabolites) have been recognized that produce this effect (Shao et al., 2005; Matawali et al., 2016). Low dose of phenolic compounds stimulates protein synthesis and activation of antioxidant enzymes (Baziramakenga et al., 1995) which are effective in plant protection (Kleiner et al., 1999), while high levels of phenolic application result in plant damage (Politycka et al., 2004). Proline accumulation in leaf tissues wase more pronounced with an increase in M. micrantha treated samples of M. uniflorum. In M. uniflorum, the maximum proline level was reported at 200 mg/ml (24.49 mg/g) followed by 100 mg (20.19 mg/g), 50 mg/ml (13.13 mg/g) and 50 mg/ml (14.83 mg/g) (Figure 5). Proline accumulation is a general phenomenon in all stressed plants (Saradhi and Vani, 1993; Lee and Liu, 1999; Hernandez et al., 2000; Dhir et al., 2004; Ahmad et al., 2006; Koca et al., 2007; Parida and Jha, 2010; Shahbaz et al., 2013). Proline also acts as a major reservoir of nitrogen and energy, that can be utilised in resuming the growth of the plant after removal of the stress (Chandrashekar and Sandhyarani, 1996).

4. Conclusions

The rate of seed germination, plant growth, biochemical parameters of M. uniflorum increased in control conditions as compared with plant exposed to different concentrations of M. micrantha extract. There was a noticeable reduction in seed germination, plant growth (shoot and root length), photosynthetic pigments and protein content in plants treated with weed extracts, while there was an increase in total phenolics and proline content. The decrease of biomolecules of M. uniflorum in the present study might be due to the release of secondary metabolites from M. micrantha. The increase in phenolics and proline content might be due to the inherent capacity of the plants to respond to different stress conditions. Higher the amount of phenolics and proline, higher the level of stress builds up in the plant system. In the present study, the weed extracts inhibit the crop plant's growth and physiology. This study will definitely lead to the identification of few phytocompounds or metabolites having beneficial agricultural applications for sustainability in near future. Sensitivity to the allelo-chemicals and extent of inhibition vary from crop to crop but it will enhance future aspects of crop protection from several harmful plant species.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Pallavi Jali; Gyanranjan Mahalik: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Ipsita Priyadarsini Samal; Sameer Jena: Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors highly acknowledge Department of Botany, School of Applied Sciences, Centurion University of Technology and Management (CUTM), Odisha, India for necessary support to conduct the present research work. Nevertheless, authors are very much thankful to the Dean, SoAS and Head, Department of Botany for necessary Laboratory facilities to carry out the work. The research work has no funding.

References

- Abdul-Baki A.A., Anderson J.D. Vigor determination in soybean seed by multiple criteria. Crop Sci. 1973;13:630–633. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad P., Sharma S., Srivastava P.S. Differential physio-biochemical responses of high yielding varieties of mulberry (Morus alba) under alkalinity (Na2CO3) stress in vitro. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants. 2006;12:59. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad P., Sharma S., Srivastava P.S. In vitro selection of NaHCO3 tolerant cultivars of Morus alba (Local and Sujanpuri) in response to morphological and biochemical parameters. Hortic. Sci. (Prague) 2007;34:114–122. [Google Scholar]

- Arnon D.I. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidases in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949;24:1. doi: 10.1104/pp.24.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu G.P., Vinita H., Audiseshamma K., Paramageetham C.H. Allelopathic effects of some weeds on germination and growth of Vigna mungo (L) Hepper. Int. J. Current Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2014;3:122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Bates L.S., Waldren R.P., Teare I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil. 1973;39:205–207. [Google Scholar]

- Baziramakenga R., Leroux G.D., Simard R.R. Effects of benzoic and cinnamic acids on membrane permeability of soybean roots. J. Chem. Ecol. 1995;21:1271–1285. doi: 10.1007/BF02027561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt A., Santo A., Gallacher D. Seed mucilage effect on water uptake and germination in five species from the hyper-arid Arabian desert. J. Arid Environ. 2016;128:73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cen Y.J., Pang X.F., Ling B., Kong C.H. Study on the active components of oviposition repellency of Mikania micrantha HBK against citrus red mite, Panonychus citri McGregor. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2004;11 [Google Scholar]

- Chandrashekar K.R., Sandhyarani S. Salinity induced chemical changes in Crotalaria striata DC plants. Indian J. Plant Physiol. 1996;1:44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng F., Cheng Z. Research progress on the use of plant allelopathy in agriculture and the physiological and ecological mechanisms of allelopathy. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:1020. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.01020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou C.H., Lin H.J. Autointoxication mechanism of Oryza sativa I. Phytotoxic effects of decomposing rice residues in soil. J. Chem. Ecol. 1976;2:353–367. [Google Scholar]

- Dai L.P., Xiong Z.T., Huang Y., Li M.J. Cadmium-induced changes in pigments, total phenolics, and phenylalanine ammonia-lyase activity in fronds of Azolla imbricata. Environ. Toxicol. 2006;21:505–512. doi: 10.1002/tox.20212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day M.D., Clements D.R., Gile C., Senaratne W.K., Shen S., Weston L.A., Zhang F. Biology and impacts of pacific islands invasive species. 13. Mikania micrantha Kunth (Asteraceae) 1. Pac. Sci. 2016;70(3):257–285. [Google Scholar]

- Dhir B., Sharmila P., Saradhi P.P. Hydrophytes lack potential to exhibit cadmium stress induced enhancement in lipid peroxidation and accumulation of proline. Aquat. Toxicol. 2004;66:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J., Wu F.B., Zhang G.P. Effect of cadmium on growth and photosynthesis of tomato seedlings. J. Zhejiang Univ. - Sci. 2005;6:974. doi: 10.1631/jzus.2005.B0974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraenkel G. The Ecology of Bruchids Attacking Legumes (Pulses) Springer; Dordrecht: 1981. Importance of Allelochemics in plant insect relations; pp. 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez S., Deleu C., Larher F. Proline accumulation by tomato leaf tissue in response to salinity. Comptes rendus de l'Academie des Sci. Serie. III, Sci. de. la. vie. 2000;323:551–557. doi: 10.1016/s0764-4469(00)00167-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.L., Fang X.T., Lu L., Yan Y.B., Chen S.F., Hu L., Shi S.H. Transcriptome analysis of an invasive weed Mikania micrantha. Biol. Plant. 2012;56:111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z., Cao H., Liang X., Ye W., Feng H., Cai C. The growth and damaging effect of Mikania micrantha in different habitats. J. Trop. Subtrop. Bot. 2000;8:131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail B.S., Mah L.S. Effects of Mikania micrantha HBK on germination and growth of weed species. Plant Soil. 1993;157:107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Jali P., Acharya S., Mahalik G., Das A.B., Pradhan C.P. Low dose cadmium (II) induced antifungal activity against blast disease in rice. Physiol. Mol. Plant P. 2019;108:101422. [Google Scholar]

- Jyothilakshmi M., Jyothis M., Latha M.S. Antidermatophytic activity of Mikania micrantha Kunth: an invasive weed. Pharmacol. Res. 2015;7:S20. doi: 10.4103/0974-8490.157994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaundal S.P., Sharma A., Kumar R., Kumar V. Exploration of medicinal importance of an underutilized legume crop, Macrotyloma uniflorum (Lam.) Verdc.(Horse gram): a review. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2019;10:3178–3186. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur R., Malhotra S. Effects of invasion of Mikania micrantha on germination of rice seedlings, plant richness, chemical properties and respiration of soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 2012;48:481–488. [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.W., Rakwal R., Agrawal G.K., Jung Y.H., Shibato J., Jwa N.S., Usui K. A hydroponic rice seedling culture model system for investigating proteome of salt stress in rice leaf. Electrophoresis. 2005;26:4521–4539. doi: 10.1002/elps.200500334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner K.W., Raffa K.F., Dickson R.E. Partitioning of 14C-labeled photosynthate to allelochemicals and primary metabolites in source and sink leaves of aspen: evidence for secondary metabolite turnover. Oecologia. 1999;119:8–418. doi: 10.1007/s004420050802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koca H., Bor M., Ozdemir F., Turkan I. The effect of salt stress on lipid peroxidation, antioxidative enzymes and proline content of sesame cultivars. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007;60:344–355. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacik J., Bačkor M. Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase and phenolic compounds in chamomile tolerance to cadmium and copper excess. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 2007;185:185–193. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar D. Horsegram research: an introduction. In: Kumar D., editor. Horse Gram in India. 2006. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Langenheim J.H. Higher plant terpenoids: a phytocentric overview of their ecological roles. J. Chem. Ecol. 1994;20:1223–1280. doi: 10.1007/BF02059809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T.M., Liu C.H. Correlation of decreased calcium contents with proline accumulation in the marine green macroalga Ulva fasciata exposed to elevated NaCl contents in seawater. J. Exp. Bot. 1999;50:1855–1862. [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Jin Z. Potential allelopathic effects of Mikania micrantha on the seed germination and seedling growth of Coix lacryma-jobi. Weed Biol. Manag. 2010;10:194–201. [Google Scholar]

- Liza K.C., Ram A.M. Allelopathic effect of extract of Mikania micrantha on seed germination and seedling growth of Melia azedarach. J. Phys. Environ. Stud. 2017;3:52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry O.H., Rosebrough N.J., Farr A.L., Randall R.J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maksymiec W., Krupa Z. The effects of short-term exposition to Cd, excess Cu ions and jasmonate on oxidative stress appearing in Arabidopsis thaliana. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2006;57:187–194. [Google Scholar]

- Mallik C.P., Singh M.B. 1980. Plant Enzymology and Histoenzymology. A Text Manual; p. 281. [Google Scholar]

- Matawali A., Chin L.P., Eng H.S., Gansau J.A. Antibacterial and phytochemical investigations of Mikania micrantha HBK (Asteraceae) from Sabah, Malaysia. Trans. Sci. Tech. 2016;3:244–250. [Google Scholar]

- Matawali A., Chin L.P., Eng H.S., Gansau J.A. Antibacterial and phytochemical investigations of Mikania micrantha HBK (Asteraceae) from Sabah, Malaysia. Trans. Sci. Techno. 2016;3:244–250. [Google Scholar]

- Mittra B., Ghosh P., Henry S.L., Mishra J., Das T.K., Ghosh S., Mohanty P. Novel mode of resistance to Fusarium infection by a mild dose pre-exposure of cadmium in wheat. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2004;42:781–787. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed H.I., Gomaa E.Z. Effect of plant growth promoting Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas fluorescens on growth and pigment composition of radish plants (Raphanus sativus) under NaCl stress. Photosynthetica. 2012;50:263–272. [Google Scholar]

- Padmaja K., Prasad D.D.K., Prasad A.R.K. Inhibition of chlorophyll synthesis in Phaseolus vulgaris L. seedlings by cadmium acetate. Photosynthetica. 1990;24:399–405. [Google Scholar]

- Parida A., Das A.B., Das P. NaCl stress causes changes in photosynthetic pigments, proteins, and other metabolic components in the leaves of a true mangrove, Bruguiera parviflora, in hydroponic cultures. J. Plant. Biol. 2002;45:28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Parida A.K., Das A.B., Mittra B. Effects of salt on growth, ion accumulation, photosynthesis and leaf anatomy of the mangrove, Bruguiera parviflora. Trees. 2004;18:167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Parida A.K., Jha B. Antioxidative defense potential to salinity in the euhalophyte Salicornia brachiata. J. Plant Grow. Regul. 2010;29:137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Patel D.D., Kumbhar B.A. Weed and its management: a major threats to crop economy. J. Pharm. Sci. Biosci. Res. 2016;6:453–758. [Google Scholar]

- Politycka B., Kozłowska M., Mielcarz B. Cell wall peroxidases in cucumber roots induced by phenolic allelochemicals. Allelopathy J. 2004;13:29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ranasinghe R.L.D.S., ERHSS E. Medicinal and nutritional values of Macrotyloma uniflorum (Lam.) verdc (kulattha): a conceptual study. Global J. Pharm. Pharmac. Sci. 2017;1:44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio M.I., Escrig I., Martinez-Cortina C., Lopez-Benet F.J., Sanz A. Cadmium and nickel accumulation in rice plants. Effects on mineral nutrition and possible interactions of abscisic and gibberellic acids. Plant Growth Regul. 1994;14:151–157. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo H., Mahalik G. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants of Kantapada block of Cuttack district, Odisha, India. Int. J. Biosci. 2020;16:284–292. [Google Scholar]

- Saradhi P.P., Vani B. Inhibition of mitochondrial electron transport is the prime cause behind proline accumulation during mineral deficiency in Oryza sativa. Plant Soil. 1993;155:465–468. [Google Scholar]

- Shahbaz M., Mushtaq Z., Andaz F., Masood A. Does proline application ameliorate adverse effects of salt stress on growth, ions and photosynthetic ability of eggplant (Solanum melongena L.)? Sci. Horticult. 2013;164:507–511. [Google Scholar]

- Shao H., Peng S., Wei X., Zhang D., Zhang C. Potential allelochemicals from an invasive weed Mikania micrantha. H.B.K. J. Chem. Ecol. 2005;31:1657–1668. doi: 10.1007/s10886-005-5805-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinde M.A., Salve J.T. Allelopathic effects of weeds on Triticum aestivum. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2019;9:19873–19876. [Google Scholar]

- Singh D.P. Kalyani Publishers; Ludhiana: 1991. Lentils in India-Genetics and Breeding of Pulse Crops; pp. 217–238. [Google Scholar]

- Stamp N. Out of the quagmire of plant defense hypotheses. Q. Rev. Biol. 2003;78:23–55. doi: 10.1086/367580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari S., Siwakoti M., Adhikari B., Subedi K. IUCN Nepal; 2005. An Inventory Assessment of Invasive Alien Plant Species of Nepal. [Google Scholar]

- Turner R.G., Marshall C. The accumulation of zinc by subcellular fractions of roots of Agrostis tenuis Sibth. in relation to zinc tolerance. New Phytol. 1972;71:671–676. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M., Suzuki T. Involvement of reactive oxygen stress in cadmium-induced cellular damage in Euglena gracilis. Comp. Biochem. Physio. Part C: Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2002;131:491–500. doi: 10.1016/s1532-0456(02)00036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim E., Turan M., Guvenc I. Effect of foliar salicylic acid applications on growth, chlorophyll, and mineral content of cucumber grown under salt stress. J. Plant Nutr. 2008;31:593–612. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Ling B., Kong C., Zhao H., Pang X. Allelopathic potential of volatile oil from Mikania micrantha. J. Appl. Ecol. 2002;13:1300–1302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y., Zheng W., Lin F., Zhang Y., Yi Y., Wang B., Wu W. AVR1-CO39 is a predominant locus governing the broad avirulence of Magnaporthe oryzae 2539 on cultivated rice (Oryza sativa L.) Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2011;24:13–17. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-10-09-0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.