Abstract

Background

In resource limited countries breast self-examination has been recommended as the most appropriate method for early detection of breast cancer. Available studies conducted on breast self-examination practice in Africa currently are inconsistent and inclusive evidences. On top of that the available studies are unrepresentative by regions with small sample size. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted to summarize and pool the results of individual studies to produce content level estimates of breast self-examination practice in Africa.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis were done among studies conducted in Africa using Preferred Item for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISRMA) guideline. Studies were identified from PubMed, Google Scholar, HINARI, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane, African Journals Online and reference lists of identified prevalence studies. Unpublished sources were also searched to retrieve relevant articles. Critical appraisal of studies was done through Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-MAStARI). The meta-analysis was conducted using STATA 13 software. Heterogeneity was assessed using I2 statistics while publication was assessed through funnel plot. Forest plot were used to present the pooled prevalence with a 95% confidence interval (CI) using the random effect model.

Results

In this meta-analysis 56 studies were included with a total of 19, 228 study participants. From the included studies 25(44.64%) were from West Africa, 22(39.29%) East Africa, 5(8.93%) North Africa, 3(5.36%) Central Africa and 1(1.79%) South Africa. The overall pooled prevalence of ever and regular breast self-examination practice in Africa was found to be 44.0% (95% CI: 36.63, 51.50) and 17.9% (95% CI: 13.36, 22.94) respectively. In the subgroup analysis there was significant variations between sub regions with the highest practice in West Africa, 58.87% (95 CI%: 48.06, 69.27) and the lowest in South Africa, 5.33% (95 CI%: 2.73, 10.17).

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that breast self-examination practice among women in Africa was low. Therefore, intensive behavioral change communication and interventions that emphasize different domains should be given by stakeholders.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42020119373.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13690-021-00671-8.

Keywords: Breast self-examination, Prevalence, Women, Africa, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Background

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in women and the leading cause of cancer death worldwide, with an estimated 1.7 million new cases and 521,900 deaths in 2012 compared to 1.38 million new cases and 458,000 deaths in 2008 [1–3]. Based on Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN) estimates, about 14.1 million new cancer cases and 8.2 million deaths occurred in 2012 worldwide [3].

The burden of cancer has shifted to low and middle income countries (LMIC), which currently account for about 57% of cases and 65% of cancer deaths worldwide [3]. Nearly 60% of deaths due to breast cancer occur in LMIC [4]. Recent global cancer statistics indicated that breast cancer incidence is rising at a faster rate in populations of LMIC [5, 6]. The age-standardized incidence rates of breast cancer incidence for the year 2012 in Africa regions were estimated as; 30.4 in eastern Africa (per 100,000 women per year), 26.8 in middle Africa, 38.6 in western Africa, 38.9 in southern Africa and, 33.8 in sub-Saharan Africa [1, 7, 8]. Morbidity and mortality of breast cancer is emerging as a major public health concerns in many LMICs [9]. The lifetime risk of a woman getting breast cancer is 1 in 10 [10]. The main reason for increasing mortality is mainly due to late diagnosis of the disease and lack of feasible early screening programs [11, 12].

Early diagnosis and survival improvement of breast cancer is a top priority to reduce the increasing mortality rate, projected to reach 112, 000 deaths in 2040 [13]. Detecting and preventing breast cancer at an early stage through feasible screening approaches is a very essential recommendation to meet sustainable development goal (SDG) 3.4 by 2030 [14]. Breast cancer is curable if detected early through screening and early diagnosis by breast self-examination (BSE), clinical breast examination (CBE), and mammography [15]. Despite the existence of controversies about the effectiveness breast self-examination in reducing mortality and morbidity [16–18], the technique remains an important approach for early detection mainly in low and middle-income countries where access to diagnostic and curative facilities may be problematic [19, 20].

Breast self-examination practice is the recommended approach in developing countries because it is easy to perform, feasible, convenient, safe and requires no specific equipment and set up [21–23]. Despite this recommendation, available studies conducted on breast self-examination practice in Africa currently are inconsistent and inclusive to inform and direct stakeholders. On top of that the available reviews lacks comprehensives since they were limited to country level with small sample size and high heterogeneity in their results. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted to summarize and pool the results of individual studies to produce continent level estimates of breast self-examination practice in Africa. The finding of the study will be contributing for designing feasible strategies, polices and guidelines to improve breast self-examination practice and also to fight against breast cancer among women in Africa.

Methods

Search strategy

This systematic review and meta-analysis was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement guideline. Pertinent published articles were searched in the following electronic bibliographic databases: PubMed, EMBASE, Science Direct, HINARI, Google scholar, WHO Global Index Medicus and African Journals Online (AJOL) were searched to retrieve all available studies. In addition, cross-references of included studies were hand-searched as well to access additional relevant articles that may have been missed in the search. We used Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) and keywords to identify relevant studies from the respective database. The search terms were used separately and together using Boolean operators “OR” or “AND”. The key word of search strategy used to retrieve relevant articles was as follows: (((“Breast Self Examination”[MeSH Terms] OR “self examination breast” OR “early detection of breast cancer” OR “breast cancer screening”])) AND (“health knowledge, attitudes, practice”[MeSH Terms]])) AND (“women”[MeSH Terms] OR “Girls” OR “Woman” OR “female” OR “females” OR “Reproductive age women” OR “reproductive aged women”])) AND (“Africa”[MeSH Terms] OR (((“Africa central”] OR “Africa eastern” OR “Africa southern” OR “Africa western” OR “Africa northern”))). The software EndNote version X8 (Tomson Reuters, New York, NY) was used to manage references and remove duplicated references. All articles published up to June 30, 2020 in English language were included in the review if fulfilled the eligibility criteria. This systematic review and meta-analysis was registered in PROSPERO with a registration number; http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42020119373

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Study design

Observational (case-control, cohort, cross-sectional) studies reporting breast self-examination practice among women in Africa were included.

Study area

Only studies conducted in Africa continent were included.

Language

Studies that were conducted only in English language were included.

Publication status

Both published and unpublished articles were included.

Publication period

All publication reported up to June 30, 2020 were included.

Population

Studies which were conducted among women in Africa.

Outcome

Women who have ever/regularly performed breast self-examination for detection of breast abnormalities and lumps.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if they were not primary studies (such as review articles, conference abstract, editorials, case reports am expert opinion). Moreover, studies not reporting the outcome variable, published in any language other than English, author contact not replied within 3 weeks, and qualitative studies were excluded.

Study selection

First, articles were assessed for inclusion through a title and abstract review by two independent reviewers. Second, potentially-eligible studies were undergoing full-text review to determine if they satisfy the criteria set for inclusion. We did a full-text review in duplicate and clearly document reasons for inclusion and exclusion. Finally, data were extracted from all articles that meet the inclusion criteria. The data extraction form was pre-tested with 3–5 eligible studies. The practice of breast self-examination was extracted if only reported and/or estimated based on experts’ opinion or previously published studies or guidelines. In case of incomplete data, the corresponding author(s) were contacted to find full information. Disagreement and unclear information in the selection of articles being included in the review were resolved through discussion and consensus.

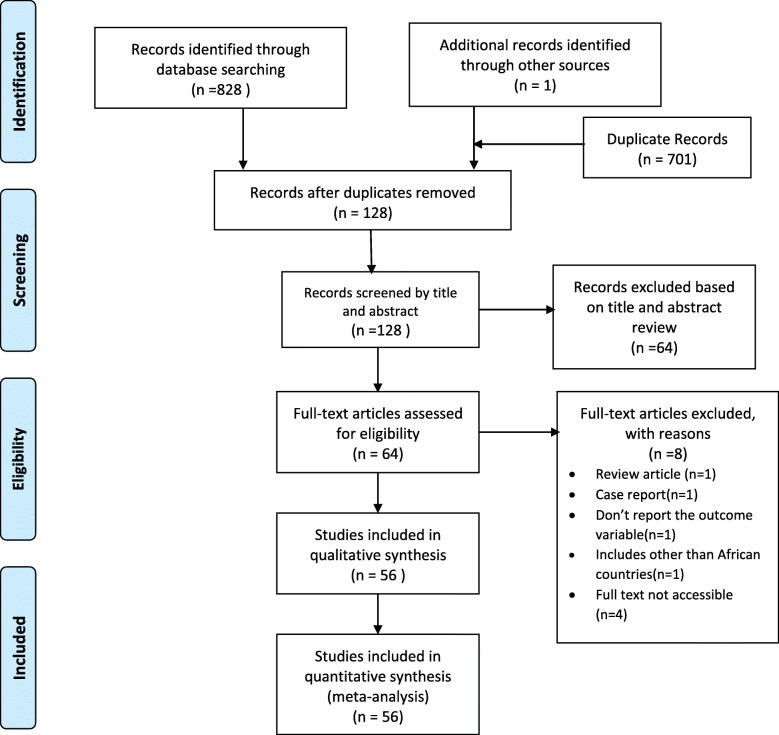

In our search we identified 829 articles from different electronic databases. From these, 701 were found duplicate records and removed from the review. Fifty-one and thirteen articles were excluded by reviewing the title and abstract respectively. After a full review of articles, eight were excluded. Three studies didn’t fulfill the inclusion criteria, one articles fail to report the outcome variables and four articles unable to get access to the full articles. Finally, 56 were found to be eligible and included in this meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart diagram describing selection of studies for a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence of breast self-examination in Africa, 2020 (identification, screening, eligible and included studies)

Outcome measures

The primary outcome variable of this study is breast self-examination practice (ever/regular) among women in Africa. Ever breast self-examination practice is defined as a woman who performed breast self-examination irregularly for the purpose of detecting and feeling any abnormal swelling or lumps in their breast tissue which was assessed through interview administered questionnaires. Regular breast self-examination practice when a woman performed breast self-examination during menses once per month which was assessed through interview administered questionnaires.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment was conducted based on Hoy 2012 tool by two reviewers using 10 criteria addressing internal and external validity [24]. The items included the following ten parameters: (1) representation of the population, (2) sampling frame, (3) methods of participants’ selection, (4) non-response bias, (5) data collection directly from subjects, (6) was an acceptable case definition used, (7) was tool shown reliability and validity, (8) was the same mode of data collection used, (9) was the length of prevalence period appropriate, and (10) were the numerator and denominator appropriate. Each item was assessed as either low or high risk of bias. Unclear was regarded as high risk of bias. In this study, each of the ten parameters in the risk of bias tool was allocated an equal weight. Therefore, the overall assessment of bias was ultimately dependent on the number of high risk parameters out of the ten parameters in the included studies. Finally, the overall risk of bias was graded as high quality (≤ 2), medium quality [3, 4], and low quality (≥ 5) based on the number of high risk parameters per individual studies (Table 1).

Table 1.

Risk of bias/quality assessment of included studies using the Hoy 2012 tool

| Study | Representation | Sampling | Random selection | Non response bias | Data collection | Case Definition | Reliability and validity of study tool | Method of data collection | Prevalence period | Numerator and denominator | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birhane et al. | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Obaji et al. | Low risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Moderate risk |

| Onwere et al. | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Moderate risk |

| Abay et al. | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Minasie A et al. | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Abdel Fattah, M et al. | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Moderate risk |

| Abeje et al. | High risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Birhane K et al. | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Carlson-Babila Sama et al. | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Kasahun AF | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Dagne AH et al. | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Dadzi R, Adam A | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Gwarzo, UMD et al | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Isara, A. R. and Ojedokun, C. I | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Segni, MT et al | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Azage M. et al | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Elshamy, Karima F et al | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Moderate risk |

| Akhigbe, A. O. et al | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Nde et al. | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Negeri et al. | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Odusanya et al | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Ogunbode A M | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High risk |

| Ossai EN et al. | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Moderate risk |

| Feleke D. et al | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Kayode F.O. et al. | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High risk |

| Okobia, Michael N et al. | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Getu et al. | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Shallo et al. | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Suh et al | Low risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Ifediora, C. O., & Azuike, E. C. | High risk | Low risk | High risk | High Risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Moderate risk |

| Ameer, K et al | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Moderate risk |

| Agboola AOJ et al | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Moderate risk |

| Amoran, O. E. and Toyobo, O. O | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Godfrey, Katende et al | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Bayumi E | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High risk |

| Bellgam H.I. amd Buowari Y. D | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Boulos, Dina NK and Ghali, Ramy R | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Moderate risk |

| E. Kudzawuet al. | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Fondjo LA et al | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Idris SA et al | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | High risk |

| Kifle MM et al | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Morse EP et al | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Ndikubwimana J et al | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Obaikol R et al | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Moderate risk |

| Ramathuba, Dorah U et al | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Ramson, Lombe Mumba | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Florence, Adeyemo O et al | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Yakubu AA et al | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Andegiorgishet al. | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Kimani, SM and Muthumbi, E | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Moderate risk |

| Agbonifoh, Julia Adesua | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Casmir, Ebirim Chikere Ifeanyi et al | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Joel Olayiwola Faronbi | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Makanjuola, OJ et al | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Olowokere et al. | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Sambo, MN et al | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

Data extraction

Data extraction of included articles was made using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) tool for prevalence studies [25]. A Microsoft excel sheet was prepared and the following information were extracted; author/s name, title, year of publication, study area and country, study design, study setting, study population, age of the study participants, sample size, response rate, prevalence of breast self-examination practice (ever/regular).

Heterogeneity and publication bias

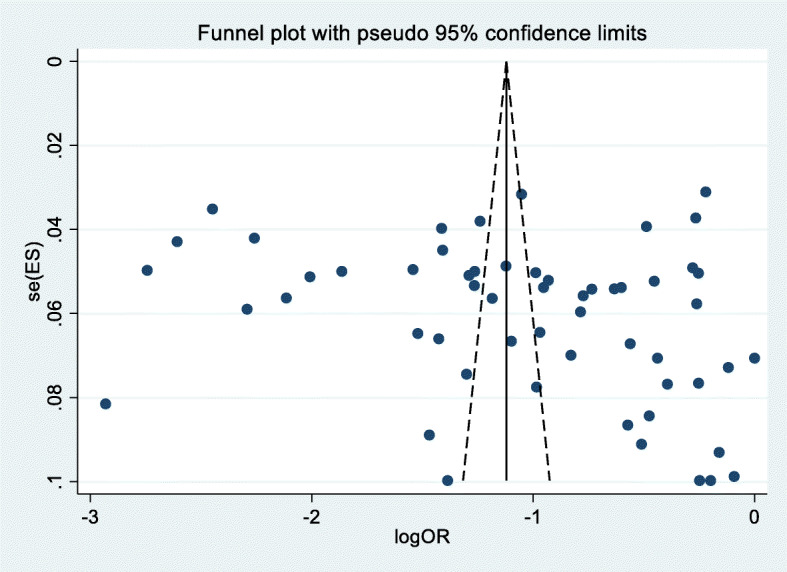

The heterogeneity of included studies was assessed by using the I2 statistics. The p-value for I2 statistics less than 0.05 were used to determine the presence of heterogeneity. I2 values of 25, 50, and 75% are assumed to represent low, moderate and high heterogeneity respectively [26]. Graphically publication bias and small study effect were evaluated by funnel plot test. We had plotted the studies’ logit event rate and standard error to detect asymmetry in the distribution. When there is a gap in the funnel plot, it indicates that is a potential for publication bias. In addition, the publication bias was assessed using the Egger regression asymmetry test [27].

Statistical analysis and synthesis

Findings were illustrated in the form of forest plots and tables. Eligible primary studies data were extracted, entered into Microsoft Excel and then exported to STATA version 13. Forest plot was used to present the combined estimate with 95% confidence interval (CI) of the meta analysis in Africa. The random effect model of analysis was used as a method of meta-analysis since it enables us to minimize the heterogeneity of included studies. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses were also conducted by different study characteristics such as sub-regions of Africa (East, South, West, Central and Northern Africa), study period (2000–2005, 2006–2010, 2011–2015, 2016–2020), setting (community/institution based), study area (urban, rural or both), study participants’ profession (health/non health professionals), and risk of bias (low, moderate and high).

Result

Characteristics of included studies

A total of 56 studies were included in this meta-analysis. Fourteen African countries were included in this review. From the included studies, 25(44.64%) were from West Africa [28–52], 22(39.29%) from East Africa [19, 53–73], 5(8.93%) from North Africa [21, 74–77], 3(5.36%) from Central Africa [78, 79], 1(1.79%) from South Africa [80]. All the included fifty-six studies in this systematic review and meta-analysis conducted in African countries were cross sectional study designs.

The sample size of the included studies ranged from a minimum of 100 in a study conducted in Nigeria [29, 49, 50] to a maximum of 1036 a study conducted in Ghana [44]. A total of 19, 228 study participants were included in this review (Table 2). Almost all 55(98.21%) of the included studies were published on peer reviewed journals while only 1(1.178%) study was unpublished [58]. Majority 43(76.79%) of the included studies were institution based while around one forth 13(23.21%) of the studies were community based [19, 28, 30, 38, 41–43, 50, 51, 62, 71, 80, 81]. From the total included studies, 10(17.86%) were conducted among health professionals [19, 33, 40, 42, 46, 54, 61, 64, 72, 75]. Majority 40 (71.43%) of the study participant were urban residents and the age of the participants ranged from 13 [32] to 85 [42] year-old.

Table 2.

Summary of characteristics of included studies in meta-analysis of breast self-examination practice in Africa

| Author/s | Year | Sub- region | Study design | Study setting | Response rate | Sample size | Event (Ever Practiced) |

Prevalence of BSE (%) | Risk of Bias | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ever BSE | Regular BSE | |||||||||

| Birhane et al. | 2015 | East Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 99.6 | 315 | 38 | 12 | Not reported | Low risk |

| Obaji et al. | 2013 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Community Based | 100 | 238 | 52 | 21.8 | 0.24 | Moderate risk |

| Onwere et al. | 2009 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 100 | 100 | 78 | 78 | 78 | Moderate risk |

| Abay et al. | 2018 | East Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 99 | 404 | 26 | 6.4 | 6.2 | Low risk |

| Minasie A et al. | 2017 | East Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 100 | 281 | 128 | 46.5 | 6.4 | Low risk |

| Abdel Fattah, M et al. | 2000 | North Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 100 | 565 | 59 | 10.4 | 2.7 | Moderate risk |

| Abeje et al. | 2019 | East Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 100 | 633 | 154 | 24.3 | 10.1 | Low risk |

| Birhane K et al. | 2017 | East Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 94 | 400 | 113 | 28.3 | 17.5 | Low risk |

| Sama, C. B. et al | 2017 | Central Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 82.1 | 345 | 133 | 38.5 | Not reported | Low risk |

| Kasahun AF | 2014 | East Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 95.2 | 400 | 62 | 15.5 | 9.25 | Low risk |

| Dagne AH et al. | 2019 | East Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 100 | 421 | 137 | 32.5 | 15.2 | Low risk |

| Dadzi R, Adam A | 2019 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Community Based | 100 | 385 | 106 | 27.5 | 16.1 | Low risk |

| Gwarzo, UMD et al | 2009 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 100 | 221 | 126 | 57 | 19 | Low risk |

| Isara, A. R. and Ojedokun, C. I | 2011 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 95.7 | 287 | 29 | 10.1 | Not reported | Low risk |

| Segni, MT et al | 2016 | East Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 100 | 368 | 145 | 39.4 | 2.3 | Low risk |

| Azage M. et al | 2013 | East Africa | Cross sectional | Community Based | 98.01 | 395 | 147 | 32.2 | 14.2 | Low risk |

| Elshamy, Karima F et al | 2010 | North Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 80 | 133 | 75 | 56.4 | 10.5 | Moderate risk |

| Akhigbe, A. O. et al | 2009 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 77.8 | 393 | 305 | 77.6 | Not reported | Low risk |

| Nde et al. | 2015 | Central Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 91.1 | 166 | 62 | 37.3 | 3 | Low risk |

| Negeri et al. | 2017 | East Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 95.5 | 300 | 231 | 77 | 33.7 | Low risk |

| Odusanya et al | 2001 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 94 | 188 | 167 | 88.9 | 61.7 | Low risk |

| Ogunbode A M | 2015 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 100 | 140 | 87 | 62 | 7.9 | High risk |

| Ossai EN et al. | 2019 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 100 | 365 | 232 | 63.6 | 15.9 | Moderate risk |

| Feleke D. et al | 2019 | East Africa | Cross sectional | Community Based | 100 | 810 | 70 | 8.6 | Not reported | Low risk |

| Kayode F.O. et al. | 2005 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 84 | 341 | 181 | 53 | 33.7 | High risk |

| Okobia, Michael N et al. | 2006 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Community Based | 95.1 | 1000 | 349 | 34.9 | Not reported | Low risk |

| Getu et al. | 2019 | East Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 100 | 407 | 87 | 21.4 | 11 | Low risk |

| Shallo et al. | 2019 | East Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 87.9 | 340 | 163 | 47.9 | 32.4 | Low risk |

| Suh et al | 2012 | Central Africa | Cross sectional | Community Based | 100 | 120 | 72 | 60 | Not reported | Low risk |

| Ameer, K et al | 2014 | East Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 100 | 126 | 29 | 23 | Not reported | Moderate risk |

| Ifediora, C. O., & Azuike, E. C. | 2018 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 74.3 | 321 | 148 | 46.1 | 6.2 | Moderate risk |

| Agboola AOJ et al | 2009 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 100 | 115 | 98 | 85.2 | 46.9 | Moderate risk |

| Amoran, O. E. and Toyobo, O. O | 2015 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Community Based | – | 495 | 121 | 24.4 | 5.23 | Low risk |

| Godfrey, Katende et al | 2016 | East Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 100 | 204 | 89 | 43.6 | 19.6 | Low risk |

| Bayumi E | 2016 | North Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 100 | 240 | 91 | 37.9 | 15.8 | High risk |

| Bellgam H.I. amd Buowari Y. D | 2012 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Community Based | 98.7 | 691 | 200 | 28.9 | Not reported | Low risk |

| Boulos, Dina NK and Ghali, Ramy R | 2013 | North Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 89.8 | 543 | 40 | 7.4 | 1.3 | Moderate risk |

| E. Kudzawuet al. | 2016 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Community Based | 100 | 170 | 132 | 77.6 | 68 | Low risk |

| Fondjo LA et al | 2018 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 100 | 1036 | 831 | 80.2 | 8.1 | Low risk |

| Idris SA et al | 2013 | North Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 88.9 | 200 | 129 | 64.5 | 64.5 | High risk |

| Kifle MM et al | 2016 | East Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 100 | 380 | 51 | 13.4 | 5.5 | Low risk |

| Morse EP et al | 2014 | East Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 100 | 225 | 75 | 33.3 | 14.2 | Low risk |

| Ndikubwimana J et al | 2016 | East Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 94.8 | 229 | 55 | 24 | 4.4 | Low risk |

| Obaikol R et al | 2010 | East Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 98.1 | 314 | 96 | 30.6 | 14 | Moderate risk |

| Ramathuba, Dorah U et al | 2015 | South Africa | Cross sectional | Community Based | 100 | 150 | 8 | 5.3 | 0 | Low risk |

| Ramson, Lombe Mumba | 2017 | East Africa | Cross sectional | Community Based | 100 | 351 | 99 | 28.2 | 12 | Low risk |

| Florence, Adeyemo O et al | 2016 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 100 | 200 | 200 | 100 | 75 | Low risk |

| Yakubu AA et al | 2014 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 100 | 102 | 93 | 91.1 | 44.1 | Low risk |

| Andegiorgishet al. | 2018 | East Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 97 | 414 | 313 | 75.6 | 45.9 | Low risk |

| Kimani, SM and Muthumbi, E | 2008 | East Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 100 | 169 | 114 | 67.5 | 20.1 | Moderate risk |

| Agbonifoh, Julia Adesua | 2016 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 93.2 | 647 | 397 | 61.4 | 18.7 | Low risk |

| Casmir, Ebirim Chikere Ifeanyi et al | 2015 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 100 | 720 | 552 | 76.7 | 32.5 | Low risk |

| Joel Olayiwola Faronbi | 2012 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 100 | 100 | 82 | 82 | 12 | Low risk |

| Makanjuola, OJ et al | 2013 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Community Based | 100 | 100 | 25 | 25 | 13 | Low risk |

| Olowokere et al. | 2012 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Community Based | 100 | 180 | 49 | 27.2 | Not reported | Low risk |

| Sambo, MN et al | 2013 | West Africa | Cross sectional | Institution based | 100 | 345 | 189 | 54.8 | 13.9 | Low risk |

Prevalence of breast self-examination practice in Africa

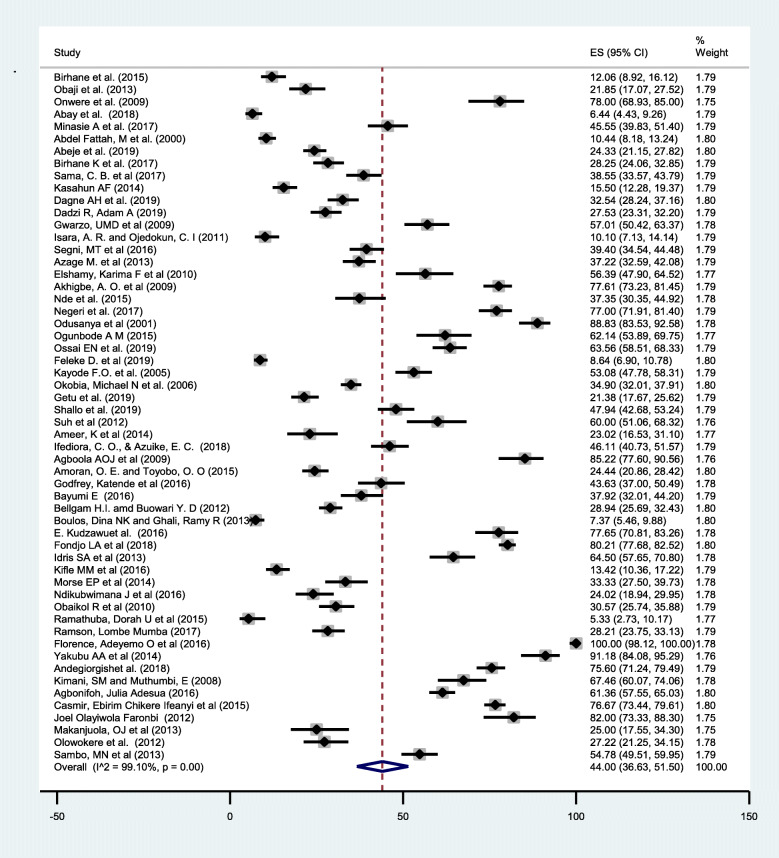

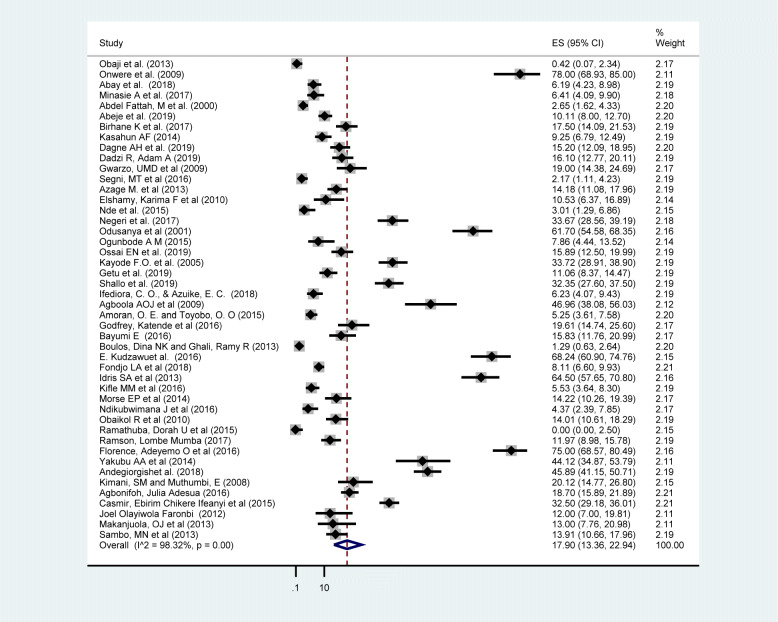

The pooled prevalence of ever breast self-examination practice in Africa was 44.0% (95% CI: 36.63, 51.50) (Fig. 2). Whereas the pooled prevalence of regular breast self-examination practice was 17.9% (95% CI: 13.36, 22.94) (Fig. 3). The lowest breast self-examination was reported in South Africa 5.3% (95% CI: 2.73, 10.17) [80] and the highest was in Nigeria 100%(95% CI: 98.12, 100.00) [45]. The prevalence of breast self-examination was highest 58.87% (95% CI: 48.06, 69.27) in West Africa followed by Central Africa 44.87% (95% CI: 32.50, 57.57), North Africa 32.63%(95% CI: 12.09–57.46), East Africa 32.18%(95%CI: 23.74,41.24) and the lowest was in South Africa 5.33% (95% CI: 2.73,10.17). The I-square test result showed that there was a high heterogeneity among the included studies (I2 = 99.10%, p-value = < 0.001). This result is an indicative to use the random effect model and subgroup analysis.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot displaying the pooled prevalence of ever breast self-examination practice among women in Africa

Fig. 3.

Forest plot displaying the pooled prevalence of regular breast self-examination practice among women in Africa

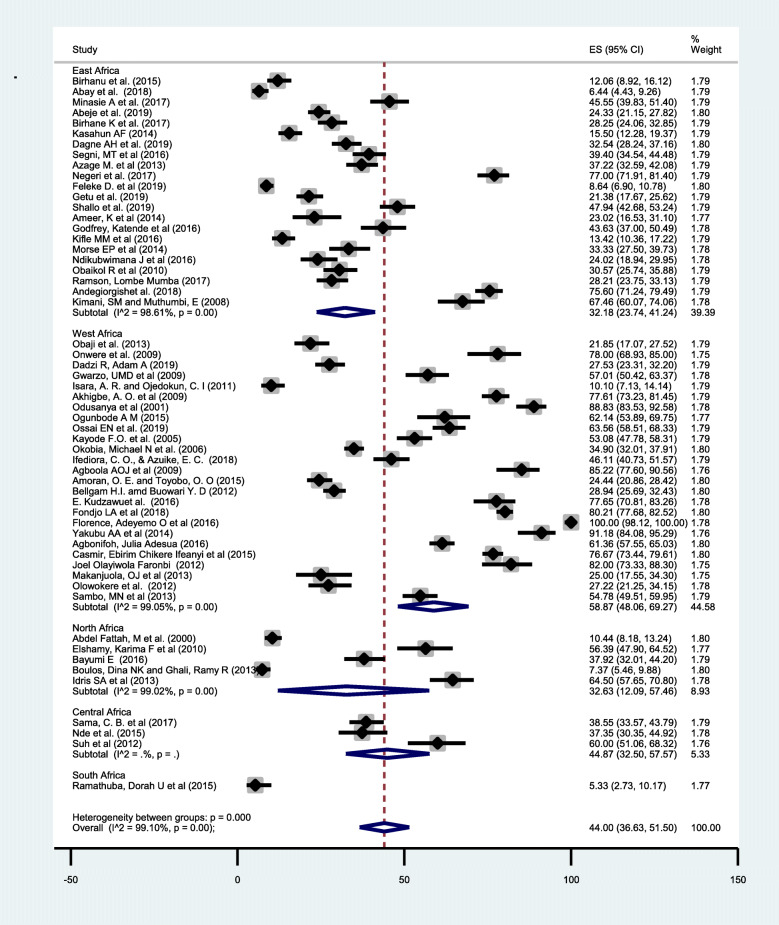

Subgroup analysis

A subgroup analysis was conducted since there was statistically significant heterogeneity, I-square test statistics less than 0.05(I2 = 99.10%, p-value = < 0.001). The purpose of the analysis was to identify the source of heterogeneity so that correct interpretation of the findings is made. We did subgroup meta-analysis of the included studies by sub region, study setting, study period, study participants, place of resident and risk of bias. However, the subgroup analysis found no significant variable which can explain the heterogeneity in this review. Therefore, the heterogeneity can be explained by other factors not included in this review.

The highest prevalence of ever breast self-examination practice was reported in West African countries 58.87% (95%CI: 48.06,69.27) while the lowest was in South African country’s 5.33% (95%CI: 2.73,10.17) (Fig. 4). A higher 48.39%(95%CI:39.39,57.44) prevalence of breast self-examination among institutional based studies compared with community-based studies 29.95% (95%CI:21.53, 39.11). In the subgroup analysis by publication period there was irregular trend in the practice of breast self-examination practice. The highest, 61.42% (95%CI:45.28, 76.39) prevalence of breast self-examination practice was reported during 2006–2010 while the lowest, 38.58% (95%CI: 27.39, 50.42) was in the period of 2011–2015. Breast self-examination practice was higher 63.33% (95% CI: 48.62, 76.88) among health professionals and urban residents 48.55% (95% CI:39.20,57.95). The prevalence of breast self-examination among low risk of bias studies was 43.20% (95%CI: 34.53, 52.08) and 54.30 (95%CI: 42.62,65.75) for high risk of bias studies (Table 3).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of ever breast self-examination practice in Africa by sub region

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis of the prevalence of breast self-examination practice in Africa

| Subgroup | Number of studies | Prevalence BSE Practice (95% CI) | Heterogeneity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 | p-value | ||||

| Sub region | West Africa | 25 | 58.87(48.06, 69.27) | 99.05 | < 0.001 |

| East Africa | 22 | 32.18 (23.74, 41.24) | 98.61 | < 0.001 | |

| North Africa | 5 | 32.63(12.09, 57.46) | 99.02 | < 0.001 | |

| Central Africa | 3 | 44.87(32.50, 57.57) | – | – | |

| South Africa | 1 | 5.33 (2.73,10.17) | – | – | |

| Study participant | Health professional | 10 | 63.33(48.62, 76.88) | 98.56 | < 0.001 |

| Non health professionals | 46 | 39.81(31.85, 48.06) | 99.12 | < 0.001 | |

| Study setting | Institutional based | 43 | 48.39(39.39,57.44) | 99.16 | < 0.001 |

| Community based | 13 | 29.95(21.53, 39.11) | 97.85 | < 0.001 | |

| Publication Period | 2000–2005 | 3 | 50.50(8.05, 92.48) | – | – |

| 2006–2010 | 8 | 61.42(45.28, 76.39) | 98.28 | < 0.001 | |

| 2011–2015 | 22 | 38.58(27.39, 50.42) | 98.88 | < 0.001 | |

| 2016–2020 | 23 | 42.34 (30.75, 54.37) | 99.29 | < 0.001 | |

| Risk of bias | Low | 41 | 43.20(34.53, 52.08) | 99.19 | < 0.001 |

| Moderate | 11 | 43.26 (26.29, 61.07) | 98.95 | < 0.001 | |

| High | 4 | 54.30 (42.62,65.75) | 92.04 | < 0.001 | |

| Place of residence | Urban | 40 | 48.55(39.20,57.95) | 99.18 | < 0.001 |

| Rural | 12 | 34.25(23.60, 45.75) | 98.36 | < 0.001 | |

| Mixed | 4 | 28.78(15.04, 44.86) | 97.15 | < 0.001 | |

| Total | 56 | 44.0% (36.63, 51.50) | 99.10 | < 0.001 | |

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was done to assess the effect of each study on the heterogeneity by excluding studies with small sample size (n < =100) and high risk of bias one by one. However, the excluded studies did not brought reduction in the heterogeneity of the estimates (Table 4).

Table 4.

Sensitivity analysis of the included studies to estimate the pooled prevalence of breast self-examination practice among women in Africa

| S. No | Study Omitted | Reason for omission | Pooled prevalence of BSE practice (95% CI) | I2 values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Ogunbode A M, 2015 | High risk of bias | 43.67(36.24–51.2) | 99.10 |

| 2. | Kayode F.O. et al., 2005 | High risk of bias | 43.84 (36.35–51.46) | 99.11 |

| 3. | Bayumi E et al., 2016 | High risk of bias | 44.11(36.63–51.73) | 99.12 |

| 4. | Idris SA et al., 2013 | High risk of bias | 43.63(36.20–51.21) | 99.11 |

| 5. | Onwere et al., 2009 | Small sample size (100) | 43.37(35.98–50.92 | 99.11 |

| 6. | Joel Olayiwola Faronbi et, 2012 | Small sample size (100) | 43.28(35.90–50.82) | 99.11 |

| 7. | Makanjuola, OJ et al., 2013 | Small sample size (100) | 44.36(36.90–51.94) | 99.12 |

Risk of bias

Studies included in this meta-analysis were assessed for risk of bias by using Hoy 2012 tool [24] (Table 1). From the 56 included studies, 41(73.21%) of them were categorized as low risk [19, 30–33, 38, 41–53, 55–64, 66–69, 71, 72, 78–83], 11(19.64%) moderate risk [28, 29, 36, 39, 40, 65, 70, 73–75, 77] and 4(7.14%) high risk of bias [21, 35, 37, 76]. It is also found that 23(41.1%) and 21(37.5%) of the included studies did not apply random selection and represent the national population respectively.

Publication bias

Small study effect of the included studies was assessed through visually and statistically. In this meta-analysis there was no publication bias since the included studies were distributed symmetrically in the funnel plot (Fig. 5). Additionally, the result of Egger’s test showed that no publication bias (p- value = 0.232).

Fig. 5.

Graphic representation of publication bias using funnel plot of included studies in systematic review and meta-analysis of breast self-examination practice among women in Africa

Discussion

In low and middle income countries, breast self-examination is one of feasible and practical options to screen breast cancer at an early stage [84, 85]. Breast self-examination has shown in reduction of incidence and death, improvement of survival rate and detection of breast cancer at an early stage [86, 87]. This systematic review and meta-analysis is paramount in showing the status of breast self-examination practice in Africa. This review showed that significant numbers of women in Africa are not practicing breast examination.

In this meta-analysis the overall pooled prevalence of ever breast self-examination practice was 44.0% (95%CI: 36.63, 51.50). The finding was comparable (44.4%) with a study conducted in Indonesia [88] among women in the age group of 20–60. However, it is higher than a nationwide cancer screening survey in South Korea (16.1%) [89] and Russia (24%) [90]. This discrepancy might be attributed due to difference in the age of the study population. In this meta-analysis majority (67.9%) of the study participant are younger age groups [20–40] and this age groups are more likely to perform breast self-examination than older one [91]. On the other hand, this finding was lower than a study conducted among nurses in Poland (100%) [91] and University staffs in Malaysia 83.7% [92]. This discrepancy might be attributed due to difference in the study population as health professionals and university staffs are more aware and skilled about breast self-examination compared to the general population.

The pooled prevalence of regular (monthly) breast self-examination practice was 17.9% (95% CI: 13.36, 22.94) which is comparable (15.2%) with a study done in Vietnam [93]. However, the finding was lower than a study done in Poland (56.7%) [91], Malaysia (41%) [92], Russia (32%) [90]. This might be attributed due to difference in culture and tradition towards breast self-examination in the study population. In addition to this, the level of awareness and information dissemination about breast self-examination frequency and interval is not well addressed in African women compared to European and Asian. This indicates that even if breast self-examination is the most feasible and affordable option to early diagnose breast cancer, African women are not practicing as per the recommended frequency and interval.

In the sub group analysis, the highest prevalence of ever breast self-examination practice was reported in West African countries 58.87% (95%CI: 48.06, 69.27) compared with other regions. The possible reason for this variation might be attributed due to the difference in the study population. In this review, 25 studies were included from West African region and among this 17(68%) of the studies were conducted among urban residents. In general, urban resident tends to have positive attitudes toward and as well as better awareness about breast self-examination. Breast self-examination practice was higher 63.33% (95% CI: 48.62, 76.88) among health professionals compared with non-health professionals. This might be attributed to the level of awareness about the disease, skill difference to perform the procedure and perception towards breast self-examination practice. Additionally, health care providers are expected to be role models for other women and because of this reason they engaged more in breast self-examination.

Limitation of the study

The estimation of the pooled prevalence of breast self-examination may have been affected by the heterogeneity, as suggested by the very high I2 statistic of 99.10%. This might be attributed to the methodological variation among the included studies. We have also included only articles published in English language and some of the included articles published on emerging journals. Some of the studies included in this review had small sample size and this might affect the pooled estimate finding. Furthermore, most of the studies included in this meta-analysis were represented from west and east African countries due to the limited number of studies in the other areas. Therefore, some regions may be underrepresented.

Conclusion

Implications for practice

This systematic review and meta-analysis found that the pooled prevalence of ever and regular breast self-examination was very low compared with other LMIC and high income countries. Even though, most literatures recommend regular breast self-examination is feasible and practical screening options for LMIC nations, the practice was not satisfactory in Africa. Therefore, intensive behavioral change communication and interventions that emphasize different domains should be given by stakeholders to increase the practice of breast self-examination in Africa.

Implications for research

In low and middle income countries breast self-examination is a feasible and beneficial approach to reduce morbidity and mortality of breast cancer through early diagnosis. Thus, further large scale follow-up studies should be conducted to identify barriers and challenges of breast self-examination practice among women in Africa.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

We author would like to thank Jigjiga University, school of public health staffs and all authors of primary studies included in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Abbreviations

- BSE

Breast self-examination practice

- CBE

Clinical breast examination

- CI

Confidence interval

- GLOBOCAN

Global Cancer Observatory

- JBI-MAStARI

Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument

- LMIC

Low and Middle Income Countries

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- SE

Standard error

- SDG

Sustainable Development Goal

Authors’ contributions

WS conceived and designed the study, preparation of protocol, analyzed data, and drafted the manuscript. WS and LM select and assess quality of studies, extract data, interpret result, and editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved final draft of manuscript.

Funding

This meta-analysis was not funded by any organization.

Availability of data and materials

All data pertaining to this review were included and presented in the document as well its supplementary files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

We author declare there is no any competing interests on the publication of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Wubareg Seifu, Email: wub2003@gmail.com.

Liyew Mekonen, Email: liy900@gmail.com.

References

- 1.World Health Organization WHO. International Agency for Research on Cancer GLOBOCAN v1.0 2012: estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012. IARC Cancer Base, No. 11.

- 2.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–EE86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parkin D. WHO, International Agency for Research on Cancer and International Association of Cancer Registries, IARC Scientific Publication. 1992. Cancer incidence in five continents, volume VI. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bray F, McCarron P, Parkin DM. The changing global patterns of female breast cancer incidence and mortality. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6(6):1–11. doi: 10.1186/bcr932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azubuike SO, Muirhead C, Hayes L, McNally R. Rising global burden of breast cancer: the case of sub-Saharan Africa (with emphasis on Nigeria) and implications for regional development: a review. World J Surg Oncol. 2018;16(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12957-018-1345-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brinton LA, Figueroa JD, Awuah B, Yarney J, Wiafe S, Wood SN, Ansong D, Nyarko K, Wiafe-Addai B, Clegg-Lamptey JN. Breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: opportunities for prevention. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;144(3):467–478. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2868-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Modeste NN, Caleb-Drayton VL, Montgomery S. Barriers to early detection of breast cancer among women in a Caribbean population. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 1999;5(3):152–156. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49891999000300003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abu-Salem OA, Hassan MA. Breast self-examination among female nurses in Jordan. Shiraz E Med J. 2007;8(2):51–7.

- 11.Parkin DM. Burden of Breast Cancer in Developing and Developed Countries. Breast Cancer Women Afr Descent Springer. 2006:1–22.

- 12.Pinotti J, Barros A, Hegg R, Zeferino L. Breast cancer control program in developing countries. Breast Dis. 1995;3(8):243–250. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, et al. Global cancer observatory: cancer today. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14.GA U . Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development. New York: Division for Sustainable Development Goals; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.HL TSS, Aghamolaei T, Zare S, Gregory D, et al. Prediction of breast self-examination in a sample of Iranian women: An application of the Health Belief Model. BMC Womens Health. 2009;9(37):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Thomas DB, Gao DL, Ray RM, Wang WW, Allison CJ, Chen FL, Porter P, Hu YW, Zhao GL, Pan LD, Li W, Wu C, Coriaty Z, Evans I, Lin MG, Stalsberg H, Self SG. Randomized trial of breast self-examination in Shanghai: final results. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(19):1445–1457. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.19.1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kösters JP, Gøtzsche PC. Regular self-examination or clinical examination for early detection of breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;2(2):1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Tarrant M. Why are we still promoting breast self-examination? Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43(4):519–520. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azage M, Abeje G, Mekonnen A. Assessment of factors associated with breast self-examination among health extension workers in west Gojjam zone, Northwest Ethiopia. Int J Breast Cancer. 2013;2013:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2013/814395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sayed S, Moloo Z, Ngugi A, Allidina A, Ndumia R, Mutuiri A, Wasike R, Wahome C, Abdihakin M, Kasmani R, Spears CD, Oigara R, Mwachiro EB, Busarla SVP, Kibor K, Ahmed A, Wawire J, Sherman O, Saleh M, Zujewski JA, Dawsey SM. Breast camps for awareness and early diagnosis of breast Cancer in countries with limited resources: a multidisciplinary model from Kenya. Oncologist. 2016;21(9):1138–1148. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Idris SA, Hamza AA, Hafiz MM, Ali MEA, El Shallaly GE. Knowledge, attitude and practice of breast self examination among final years female medical students in Sudan. Breast Cancer. 2013;116:58.0. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gemta E, Bekele A, Mekonen W, Seifu D, Bekurtsion Y, Kantelhardt E. Patterns of breast Cancer among Ethiopian patients: presentations and histopathological features. J Cancer Sci Ther. 2019;11:038–042. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Secginli S, Nahcivan N. Breast self examination remains an important component of breast health: a response to Tarrant (2006) Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;4(43):521–523. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, March L, Bain C, Baker P, Smith E, Buchbinder R. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(9):934–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthcare. 2015;13(3):147–153. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Obaji N, Elom H, Agwu U, Nwigwe C, Ezeonu P, Umeora O. Awareness and practice of breast self. Examination among market women in Abakaliki, south East Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3(1):7–12. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.109457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Onwere S, Okoro O, Chigbu B, Aluka C, Kamanu C, Onwere A. Breast self-examination as a method of early detection of breast cancer: knowledge and practice among antenatal clinic attendees in south eastern Nigeria. Pak J Med Sci. 2009;25(1):122–125. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dadzi R, Adam A. Assessment of knowledge and practice of breast self-examination among reproductive age women in Akatsi south district of Volta region of Ghana. PLoS One. 2019;14(12):e0226925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gwarzo U, Sabitu K, Idris S. Knowledge and practice of breast self-examination among female undergraduate students. Ann Afr Med. 2009;8(1):55–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Isara AR, Ojedokun CI. Knowledge of breast cancer and practice of breast self examination among female senior secondary school students in Abuja, Nigeria. J Prev Med Hygiene. 2011;52(4):186–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akhigbe AO, Omuemu VO. Knowledge, attitudes and practice of breast cancer screening among female health workers in a Nigerian urban city. BMC Cancer. 2009;9(1):203. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Odusanya OO. Breast cancer: knowledge, attitudes, and practices of female schoolteachers in Lagos, Nigeria. Breast J. 2001;7(3):171–175. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.1998.410062.x-i1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ogunbode AM, Fatiregun AA, Ogunbode OO. Breast self-examination practices in Nigerian women attending a tertiary outpatient clinic. Indian J Cancer. 2015;52(4):520–524. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.178376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ossai EN, Azuogu BN, Ogaranya IO, Ogenyi AI, Enemor DO, Nwafor MA. Predictors of practice of breast self-examination: a study among female undergraduates of Ebonyi State University, Abakaliki, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2019;22(3):361–369. doi: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_482_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kayode F, Akande T, Osagbemi G. Knowledge, attitude and practice of breast self examination among female secondary school teachers in Ilorin, Nigeria. Eur J Sci Res. 2005;10(3):42–47. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okobia MN, Bunker CH, Okonofua FE, Osime U. Knowledge, attitude and practice of Nigerian women towards breast cancer: a cross-sectional study. World J Surg Oncol. 2006;4(1):11. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ifediora CO, Azuike EC. Tackling breast cancer in developing countries: insights from the knowledge, attitudes and practices on breast cancer and its prevention among Nigerian teenagers in secondary schools. J Prev Med Hygiene. 2018;59(4):E282–e300. doi: 10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2018.59.4.964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Agboola A, Deji-Agboola A, Oritogun K, Musa A, Oyebadejo T, Ayoade B. Knowledge, attitude and practice of breast self examination in female health workers in Olabisi Onabanjo university teaching hospital, Sagamu, Nigeria. IIUM Med J Malaysia. 2009;8(1):5–10.

- 41.Amoran OE, Toyobo OO. Predictors of breast self-examination as cancer prevention practice among women of reproductive age-group in a rural town in Nigeria. Nigerian Med J. 2015;56(3):185–189. doi: 10.4103/0300-1652.160362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bellgam HI, Buowari YD. Knowledge, attitude and practice of breast self examination among women in Rivers state, Nigeria. Nigerian Health J. 2012;12(1):16–18. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kudzawu E, Agbokey F, Ahorlu CS. A cross sectional study of the knowledge and practice of self-breast examination among market women at the makola shopping mall, Accra, Ghana. Adv Breast Cancer Res. 2016;5(3):111–120. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fondjo LA, Owusu-Afriyie O, Sakyi SA, Wiafe AA, Amankwaa B, Acheampong E, et al. Comparative assessment of knowledge, attitudes, and practice of breast self-examination among female secondary and tertiary school students in Ghana. Int J Breast Cancer. 2018;2018:7502047. doi: 10.1155/2018/7502047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Florence AO, Felicia AE, Dorcas AA, Ade-Aworetan FA. An assessment of the knowledge and practice of self breast examination (BSE) amongst university students. Health. 2016;8(5):409–415. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yakubu A, Gadanya M, Sheshe A. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of breast self-examination among female nurses in Aminu Kano teaching hospital, Kano, Nigeria. Nigerian J Basic Clin Sci. 2014;11(2):85. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Agbonifoh JA. Breast self examination practice among female students of tertiary institutions. J Educ Pract. 2016;7(12):11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Casmir ECI, Anyalewechi NE, Onyeka ISN, Agwu ACO, Regina NC. Knowledge and practice of breast self-examination among female undergraduates in South-Eastern Nigeria. Health. 2015;7(09):1134–1141. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Faronbi JO, Abolade J. Breast self examination practices among female secondary school teachers in a rural community in Oyo State, Nigeria. Open J Nurs. 2012;02(02):4. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Makanjuola O, Amoo P, Ajibade B, Makinde O. Breast cancer: knowledge and practice of breast self examination among women in rural community of Ondo state Nigeria. IOSR J Pharm Biol Sci. 2013;8(1):32–37. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Olowokere AE, Onibokun AC, Oluwatosin O. Breast cancer knowledge and screening practices among women in selected rural communities of Nigeria. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sambo M, Idris S, Dahiru I, Gobir A. Knowledge and practice of self-breast examination among female undergraduate students in a northern Nigeria university. J Med Biomed Res. 2013;12(2):62–68. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abay M, Tuke G, Zewdie E, Abraha TH, Grum T, Brhane E. Breast self-examination practice and associated factors among women aged 20–70 years attending public health institutions of Adwa town, North Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):622. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3731-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Minasie A, Hinsermu B, Abraham A. Breast self-examination practice among female health extension workers: a cross sectional study in Wolaita zone, southern Ethiopia. Reprod Syst Sex Disord. 2017;6(4):2161–038X. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abeje S, Seme A, Tibelt A. Factors associated with breast cancer screening awareness and practices of women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0695-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Birhane K, Alemayehu M, Anawte B, Gebremariyam G, Daniel R, Addis S, Worke T, Mohammed A, Negash W. Practices of breast self-examination and associated factors among female Debre Berhan University students. Int J Breast Cancer. 2017;2017:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2017/8026297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Birhane N, Mamo A, Girma E, Asfaw S. Predictors of breast self-examination among female teachers in Ethiopia using health belief model. Arch Public Health. 2015;73(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s13690-015-0087-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kasahun A. Assessment of breast cancer knowledge and practice of breast self-examination among female students in Madawalabu University. Bale: Addis Ababa University; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dagne AH, Ayele AD, Assefa EM. Assessment of breast self- examination practice and associated factors among female workers in Debre Tabor town public health facilities, north West Ethiopia, 2018: cross- sectional study. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0221356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Segni M, Tadesse D, Amdemichael R, Demissie H. Breast self-examination: knowledge, attitude, and practice among female health science students at Adama science and Technology University, Ethiopia. Gynecol Obstet (Sunnyvale) 2016;6(368):2161–0932. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Negeri EL, Heyi WD, Melka AS. Assessment of breast self-examination practice and associated factors among female health professionals in Western Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Int J Med Med Sci. 2017;9(12):148–157. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Agide FD, Garmaroudi G, Sadeghi R, Shakibazadeh E, Yaseri M, Koricha ZB. Likelihood of breast screening uptake among reproductive-aged women in Ethiopia: a baseline survey for randomized controlled trial. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2019;29(5):577–584. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v29i5.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Getu MA, Kassaw MW, Tlaye KG, Gebrekiristos AF. Assessment of breast self-examination practice and its associated factors among female undergraduate students in Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2016. Breast Cancer. 2019;11:21. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S189023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shallo SA, Boru JD. Breast self-examination practice and associated factors among female healthcare workers in west Shoa zone, Western Ethiopia 2019: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):637. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4676-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ameer K, Abdulie SM, Pal SK, Arebo K, Kassa GG. Breast cancer awareness and practice of breast self-examination among female medical students in Haramaya University, Harar, Ethiopia. Ethiopia IJIMS. 2014;2(2):109–119. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Godfrey K, Agatha T, Nankumbi J. Breast cancer knowledge and breast self-examination practices among female university students in Kampala, Uganda: a descriptive study. Oman Med J. 2016;31(2):129–134. doi: 10.5001/omj.2016.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kifle MM, Kidane EA, Gebregzabher NK, Teweldeberhan AM, Sielu FN, Kidane KH, et al. Knowledge and practice of breast self-examination among female college students in Eritrea. AJPHR. 2016;4(4):104–108. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morse EP, Maegga B, Joseph G, Miesfeldt S. Breast cancer knowledge, beliefs, and screening practices among women seeking care at district hospitals in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Breast Cancer. 2014;8(BCBCR):S13745. doi: 10.4137/BCBCR.S13745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ndikubwimana J, Nyandi J, Mukanyangezi MF, Kadima JN. Breast cancer and breast self examination: awareness and practice among secondary school girls on Nyarungenge district, Rwanda. Int J Trop Dis Health. 2016;12(2):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Obaikol R, Galukande M, Fualal J. Knowledge and practice of breast self examination among female students in a sub Saharan African University. East Central Afr J Surg. 2010;15(1):22–27. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ramson LM. Knowledge, attitude and practice of breast self-examination for early detection of beast cancer among women in Roan constituency in Iuanshya, Copperbelt province, Zambia. Asian Pac J Health Sci. 2017;4(3):74–82. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Andegiorgish AK, Kidane EA, Gebrezgi MT. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of breast Cancer among nurses in hospitals in Asmara. Eritrea BMC Nurs. 2018;17(1):33. doi: 10.1186/s12912-018-0300-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kimani S, Muthumbi E. Breast self examination and breast cancer: Knowledge and practice among female medical students in a Kenyan university. Ann Afr Surg. 2008;3(1):37–42.

- 74.Abdel-Fattah M, Zaki A, Bassili A, el-Shazly M, Tognoni G. Breast self-examination practice and its impact on breast cancer diagnosis in Alexandria, Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 2000;6(1):34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Elshamy KF, Shoma AM. Knowledge and practice of breast cancer screening among Egyptian nurses. Afr J Haematol Oncol. 2010;1(4):122–8.

- 76.Bayumi E. Breast self-examination (BSE): knowledge and practice among female faculty of physical education in Assuit, South Egypt. J Med Physiol Biophys. 2016;25:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boulos DN, Ghali RR. Awareness of breast cancer among female students at Ain Shams University, Egypt. Global J Health Sci. 2013;6(1):154–161. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v6n1p154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sama CB, Dzekem B, Kehbila J, Ekabe CJ, Vofo B, Abua NL, et al. Awareness of breast cancer and breast self-examination among female undergraduate students in a higher teachers training college in Cameroon. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;28:91. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2017.28.91.10986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nde FP, Assob JC, Kwenti TE, Njunda AL, Tainenbe TR. Knowledge, attitude and practice of breast self-examination among female undergraduate students in the University of Buea. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:43. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1004-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ramathuba DU, Ratshirumbi CT, Mashamba TM. Knowledge, attitudes and practices toward breast cancer screening in a rural south African community. Curationis. 2015;38(1):1–8. doi: 10.4102/curationis.v38i1.1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Suh MAB, Atashili J, Fuh EA, Eta VA. Breast self-examination and breast cancer awareness in women in developing countries: a survey of women in Buea, Cameroon. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Minasie A, Hinsermu B, Abraham A. Breast self-examination practice among female health extension workers: a cross sectional study in Wolaita zone, Southern Ethiopia. Reprod Syst Sex Disord. 2017;6(4):219. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Odusanya OO, Tayo OO. Breast cancer knowledge, attitudes and practice among nurses in Lagos, Nigeria. Acta oncologica (Stockholm, Sweden) 2001;40(7):844–848. doi: 10.1080/02841860152703472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Anderson BO, Shyyan R, Eniu A, Smith RA, Yip CH, Bese NS, Chow LWC, Masood S, Ramsey SD, Carlson RW. Breast cancer in limited-resource countries: an overview of the breast health global initiative 2005 guidelines. Breast J. 2006;12(s1):S3–S15. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2006.00199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bonsu AB, Ncama BP. Evidence of promoting prevention and the early detection of breast cancer among women, a hospital-based education and screening interventions in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13643-018-0889-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Foster RS Jr, Costanza MC. Breast self-examination practices and breast cancer survival. Cancer. 1984;53(4):999–1005. 10.1002/1097-0142(19840215)53:4<999::AID-CNCR2820530429>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 87.Shetty MK. Breast and gynecological cancers: an integrated approach for screening and early diagnosis in developing countries: Springer Science & Business Media. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dewi TK, Massar K, Ruiter RAC, Leonardi T. Determinants of breast self-examination practice among women in Surabaya, Indonesia: an application of the health belief model. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1581. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7951-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yoo B-N, Choi KS, Jung K-W, Jun JK. Awareness and practice of breast self-examination among Korean women: results from a nationwide survey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(1):123–125. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Levshin V, Fedichkina T, Droggachih V. The experience of breast cancer screening. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34(1005):S95-S. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Woynarowska-Sołdan M, Panczyk M, Iwanow L, Bączek G, Gałązkowski R, Gotlib J. Breast self-examination among nurses in Poland and their reparation in this regard. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2019;26(3):450–455. doi: 10.26444/aaem/102762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dahlui M, Ng C, Al-Sadat N, Ismail S, Bulgiba A. Is breast self examination (BSE) still relevant? A study on BSE performance among female staff of University of Malaya. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12(2):369–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tuyen DQ, Dung TV, Dong HV, Kien TT, Huong TT. Breast self-examination: knowledge and practice among female textile Workers in Vietnam. Cancer Control. 2019;26(1):1073274819862788. doi: 10.1177/1073274819862788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data pertaining to this review were included and presented in the document as well its supplementary files.