Significance

From Imperial Rome to North Korea, religious persecution entwined with various degrees of totalitarian control has caused conflict and bloodshed for millennia. In this paper, we ask the following: Can religious persecution have repercussions long after it has ceased? Using data on the Spanish Inquisition, we show that in municipalities where the Spanish Inquisition persecuted more citizens, incomes are lower, trust is lower, and education is markedly lower than in other comparable towns and cities. Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition to still matter today, but it does.

Keywords: religion, persistence, Spain, persecution

Abstract

Religious persecution is common in many countries around the globe. There is little evidence on its long-term effects. We collect data from all across Spain, using information from more than 67,000 trials held by the Spanish Inquisition between 1480 and 1820. This comprehensive database allows us to demonstrate that municipalities of Spain with a history of a stronger inquisitorial presence show lower economic performance, educational attainment, and trust today. The effects persist after controlling for historical indicators of religiosity and wealth, ruling out potential selection bias.

Religious freedom is a basic human right, but it is under threat in many parts of the world. Some countries like Saudi Arabia expressly forbid all religions except one; others, like North Korea, do not permit any religion at all. The 2018 annual report of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom lists 28 countries—home to 57% percent of the world population—as actively persecuting citizens for their religious views (1). Religious intolerance is not new. From the Roman Emperor Nero’s outlawing of Christians to the Armenian genocide in Turkey after WWI and attacks on the Rohingya in modern-day Myanmar, religious factors have played an important role in the persecution of minorities, social upheavals, civil war, and interstate conflict (2–4).

Beginning with Max Weber’s work on Protestantism and modern growth, a rich literature has examined the relationship between religion and economic performance (5–7). On the one hand, monotheistic religions may contribute to the evolution of pro-social norms, fostering the idea of omniscient, all-powerful “Big Gods” (5) while breaking down growth-impeding social structures (7). At the same time, many religions discourage education and science (8) and view economic success with skepticism. In the cross-section of countries, church attendance is associated with lower growth, while beliefs in heaven and hell correlate positively with economic performance (9). What has received less attention are the long-run consequences of religious persecution and state-imposed religious homogeneity and in particular, how religion in the hands of a powerful state can become a tool for totalitarian rule, affecting every aspect of people’s lives (10). Many state religions persecute nonbelievers and those who deviate from doctrinal orthodoxy. Religion is often opposed to scientific inquiry and can be associated with low educational attainment (11); where persecuted minorities are more educated than the population in general, the associated loss of human capital may be particularly severe (4, 12). Religious uniformity as a means of supporting the legitimacy of the ruler may also be an obstacle to the development of state capacity, resulting in slower development (13). Persecution often relies on denunciations from local neighbors, colleagues, and friends, undermining trust. Instrumentalized religion can therefore become part and parcel of totalitarian control of people’s lives, with severe repercussions for how society functions, destroying trust and social cooperation (14). For example, regions with high trust have happier populations, more financial intermediation, higher life expectancy, and lower infant mortality (15–18). Education, trust, and state capacity facilitate economic exchange and are positively correlated with per capita income around the globe (19–22).

In this paper, we investigate the long-run impact of religious persecution on economic performance, education, and trust. The Spanish Inquisition is among the most iconic examples of a state-sponsored apparatus enforcing religious homogeneity. The Inquisition was “one of the most effective means of thought control that Europe has ever known” (10). Recent analyses have highlighted its focus on social control (23–25), its role as a repressive tool of the state (26, 27), and innovations in judicial procedure (28). Histories of Spain’s decline and fall as an economic power frequently emphasize the role of the Inquisition (29), and sociological studies have argued for a “persistence of the inquisitorial mind” in modern-day Spanish thought (30). At the same time, there are questions about its contemporary and modern-day consequences: some in-depth historical accounts of the Inquisition argue that it had a limited impact on social interactions, economic development, and intellectual life (31, 32). The notion that religious persecution leads to poor economic, social, and educational outcomes is not new, but it has largely remained beyond the reach of formal measurement and documentation of concrete mechanisms [one exception is recent work by Squicciarini (11)]. By shedding light on the mechanism responsible for the Inquisition's long-term impact, we also contribute to the literature on historical persistence (33).

Materials and Methods

We examine the records of more than 67,000 trials conducted by the Spanish Inquisition over the period 1478 through 1834 and combine this information with modern-day survey data on trust and socioeconomic status as well as information on income proxies and education (34). Where the Inquisition made its presence felt more often or conducted more trials, economic activity is markedly lower today. Levels of trust and educational attainment are lower as well, while religiosity is higher. Using historical indicators of religiosity and wealth, we show that the Inquisition did not focus its efforts on particularly poor or religious areas. Therefore, our results are not simply the product of economic backwardness or religious fervor persisting since the Middle Ages. Coarsened exact matching estimation, in which we only compare geographical units with high levels of similarity, reinforces this conclusion, including for other modern-day outcomes.

Historical Background

The Spanish Inquisition was established in 1478 and was only dissolved in 1834. Its charge was to combat heresy, defined as deviation from Catholic doctrine. It persecuted tens of thousands of individuals over the course of its 356-y history for crimes ranging from crypto-Judaism and Lutheranism to blasphemy and witchcraft. Its reach extended into almost every corner of Spain’s global empire and affected all strata of society, from simple peasants to kings themselves. Up to 10% of those tried were clergy; one-quarter were women.

The Inquisition was organized in territorial tribunals, of which there were 16 in the territory of modern-day Spain and five in overseas possessions. Tribunals were headed by three inquisitors each and relied on a network of ecclesiastical officials (“comisarios”) and unpaid lay collaborators (“familiars”). Tribunal boundaries, mostly designed to cover equally sized portions of the territory, were settled by 1526 and remained virtually unchanged for the next three centuries (35).

Trials originated with secret denunciations. According to Dedieu (28), these went through a double round of review by the prosecutor and the tribunal. If there was a sufficiently strong case against the accused, he or she was arrested, held in special jails, and tried according to a tightly regimented procedure. Trials typically lasted several years. For those convicted, penalties ranged from mild admonishments to burning at the stake. Sentences both mild and strong were typically handed down in large public ceremonies—the infamous “autos de fe”—ensuring wide publicity of the Inquisition’s activities. Executions were carried out by the secular authorities.

While confessions under torture were not rare, they could only be used in certain types of trials (those for major heresies) and, at least in theory, could be considered evidence only if the accused did not recant afterward. Community involvement was key for the Inquisition. Its local presence consisted largely of the network of “familiares,” for whom the prestige associated with their position was often the only reward. The central pieces of evidence in a case almost always took the form of testimony from the accused’s relatives, acquaintances, and extended social network.

While judicial procedures remained largely unaltered while the Inquisition was in operation, the intensity of persecution, the types of charges, and the severity of sentences all varied to reflect evolving social, political, and religious paradigms. During its heyday in the mid-sixteenth century, the Inquisition probed all kinds of social interactions, with a heavy emphasis on the policing of speech. More than one-quarter of its trials were for “heretical propositions,” which encompassed both theological writings that ran afoul of official doctrine as well as oral statements deemed blasphemous (36). Toward the end of the eighteenth century, when liberal ideas had gained a strong foothold in Spanish politics and society, tribunals conducted many fewer trials, often ending in acquittals. Nonetheless, for much of its history, the Inquisition cast a shadow over all social interactions, undermining the strength of “social capital”—the ability of citizens to solve collective problems informally through regular, free interactions (37).

Data.

We compile a database on inquisitorial trials, containing a total of 67,521 individual records. Of these, 43,526 were collected directly from primary sources, as part of the Early Modern Inquisition Database (EMID) collaborative project (38). This effort updates and digitizes the early cataloguing by Gustav Henningsen and Jaime Contreras, vastly expanding the information collected on each case (36, 39). The EMID project focuses mostly on the period 1540 through 1700, during which Inquisition tribunals produced annual reports with summaries of every case (“relaciones de causas”). This period also coincided with the peak of Inquisitorial activity. To cover the years before and after, we collect additional information on individual trials from a wide range of secondary sources (40–46).

The coverage of our data varies widely across the 16 inquisitorial tribunals. We have nearly complete records from the Toledo and Cuenca courts and high coverage for Murcia, Barcelona, and Madrid. Conversely, the surviving documentation from the Valladolid tribunal is particularly scarce, and Seville, Córdoba, and Granada also suffer from poor coverage. Because of poor data availability, as well as their remote location, we exclude the Canary Islands from the analysis. SI Appendix, Fig. A.1 provides a heatmap of data density by tribunal and year. Our database contains a nonzero number of trials for 2,244 tribunal–year pairs (44% of the total) with a peak coverage of over 70% between 1560 and 1650. Accordingly, accounting for missing data matters for our analysis.

Our data allow us to estimate the total number of trials conducted by the Inquisition. We estimate the equation:

where is the number of trials conducted by tribunal k in year t, is the tribunal fixed-effect, and is the year fixed-effect. We then use the estimates and to calculate predicted values for the number of trials in years with missing data. This simple methodology yields an overall estimate of 135,967 trials throughout the life of the Inquisition. This is consistent with the recent historiography, which has offered tentative guesses of between 115,000 and 135,000 trials (47). SI Appendix, Fig. A.2 shows a 10-y moving average of our trial estimates as well as 95% CIs.

For each entry in our database, we use the available information to establish the location where the effect of the trial would have been felt the most. This is taken to be either the place of residence of the accused, their place of birth, or the place where the alleged offense took place, in that order of preference. A total of 57,924 observations can thus be geo-referenced to a modern-day municipality. The data from EMID also contain information on name, gender, and age of the accused, type of offense, verdict, and, if found guilty, type of punishment. Relative to other “counting” efforts, our database provides a broader spatial and temporal coverage as well as substantively richer detail for a large subset of the data (47).

In addition to the historical data, we also collect the responses to the opinion barometer surveys conducted by the Spanish Center for Sociological Research (CIS). We obtained the individual response data, geocoded to the municipality, for 70 surveys, with 2,000 respondents each, conducted between 2000 and 2015, under a confidentiality agreement. From them, we compiled municipal estimates of a variety of individual socioeconomic indicators as well as a measure of trust. Despite the large number of individual responses, coverage is not universal, but CIS selects municipalities so that responses are nationally representative. Religiosity information is available for 2,766 out of 8,122 municipalities, socioeconomic standing for 2,824, and trust data for 1,150.

Variation in Inquisitorial Intensity

Our geographical unit of analysis is the modern-day municipality. We focus on “inquisitorial intensity”—the number of years when the Inquisition persecuted at least one member of a particular community as a proportion of the number of years with surviving data. Like most repressive institutions, the Inquisition exerted its influence more through fear instilled by a few visible examples rather than through actual widespread surveillance and regular violence (32).* Our choice of inquisitorial intensity as our preferred treatment variable reflects this observation. As a robustness check, we also compute a second treatment variable based on the frequency of trials in a municipality. To account for missing data, we define our “trial frequency” variable as the total number of trials linked to a municipality throughout the life of the Inquisition divided by the number of years for which data exist. All results presented in the main text, using our preferred measure of inquisitorial intensity, also obtain when using trial frequency instead. In computing both variables, we use only surviving data. No imputation is applied.

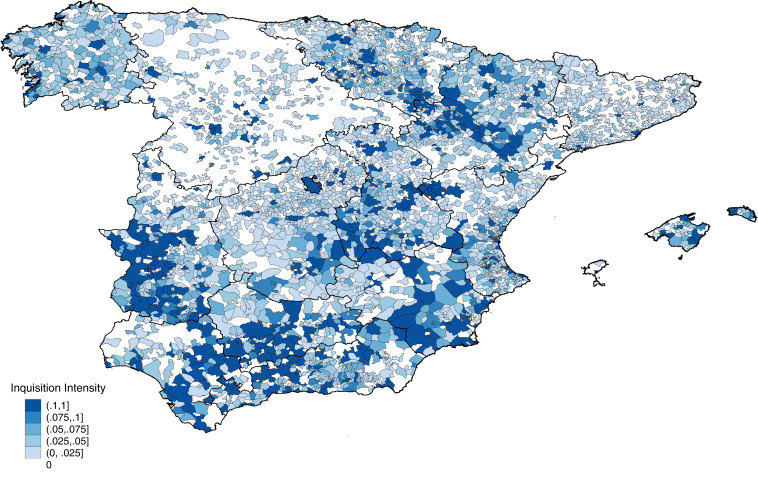

Fig. 1 shows how the intensity of persecution varied across the territory of modern-day Spain; internal divisions are tribunal boundaries. Southern tribunals saw a relatively higher intensity of persecution. Parts of the kingdom of Aragon to the northeast of the map also stand out as hot spots. The Inquisition’s arm even reached the most remote areas, including secluded valleys in the Pyrenees and most municipalities of the Balearic Islands.

Fig. 1.

Inquisitorial intensity in Spain. Note that the map gives values for inquisitorial intensity by municipality for the period 1478 through 1834. Intensity is defined as the number of years that a municipality experienced at least one inquisition trial divided by the number of years for which municipality-level data are available.

About half of all municipalities have no recorded trials against their residents. The nature of our data does not make it possible to distinguish precisely between missing data and true absence of activity. For tribunals with largely complete records, white areas are likely to have been untouched by the Inquisition; in other courts, missing data does not allow a clear determination (such as in the Valladolid tribunal, the sparsely colored patch in the northwest). In the analysis that follows, we refer to municipalities with an inquisitorial intensity value of zero—slightly over 53% of the total—as “low impact” to reflect the possibility that trials took place there in years for which the documentary evidence has been lost.† Since low-impact areas are sparsely populated, our data imply that a total of 36 million Spaniards today live in areas affected historically by the Inquisition; only 8.1 million live in areas that have no recorded impact.

Economic Consequences

What are the economic effects of 350 y of religious persecution, denunciations, interrogations, and intrusive thought control? In Spain, estimating gross domestic product (GDP) at the municipal level from administrative data are fraught with data availability and compliance problems.‡ Nightlight is highly correlated with per capita income (49, 50) and widely used as a proxy for economic performance in the development literature (22, 51, 52). We use measured nightlight variation to obtain estimates of GDP per capita at the municipal level. We first compute the residuals of a regression of median nightlight in a municipality on population. We then rescale this variable using the coefficients from a regression of these residuals on available municipal GDP data to arrive at an estimate of municipal GDP per capita denominated in euros for every Spanish municipality. SI Appendix, Appendix B describes this procedure in detail.

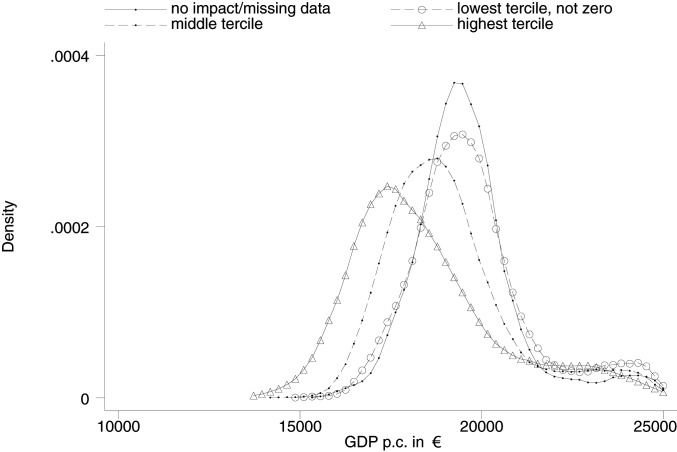

Fig. 2 shows four distributions. The solid line gives the distribution of economic activity for municipalities with no recorded Inquisition presence (n = 4,345). We split the rest into three equally sized groups (except for ties). Municipalities with no recorded inquisitorial activity as well those in the lowest tercile of persecution have the highest GDP per capita today. Those affected but in the middle tercile already have markedly lower income. Where the Inquisition struck with highest intensity (top tercile), the level of economic activity in Spain today is sharply lower. Magnitudes are large: In places with no persecution, median GDP per capita was 19,450€; where the Inquisition was active in more than 3 y out of 4, it is below 18,000€. For a municipality with average GDP per capita, a one-SD increase in inquisitorial intensity (0.058) is associated with a 330-€ decline in average annual income per capita, while going from the 75% to the 99% percentile reduces income by 1,428€. Our estimates imply that had Spain not suffered from the Inquisition, its annual national production today would be 4.1% higher—or 811€ for every man, woman, and child.§

Fig. 2.

Inquisitorial intensity and economic performance.

Column 1 in Table 1 shows the association between inquisitorial intensity and income when controlling for population, socioeconomic and geographic characteristics, and tribunal and regional fixed-effects and excluding the cities that hosted the tribunals, which naturally exhibited abnormally high levels of inquisitorial activity (ideally, one would estimate with inquisitor fixed effects, but granular information on their identity and activities has not survived with sufficient frequency). SI Appendix, Table A.1 in SI Appendix, Appendix A shows that the association is robust to using different subsets of these controls, while SI Appendix, Table A.2 demonstrates that the use of trial frequency as the treatment variable yields similar results. SI Appendix, Table A.3 explores the robustness of the specification to alternative measures of income. The results survive using an unscaled version of nightligh, as well as levels instead of logs. We also report results obtained using municipal GDP estimates constructed by the Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas on the basis of income tax returns, which yields less precisely estimated results, though still of the expected sign. This measure, as discussed above, is only available for 36% of Spanish municipalities and is prone to strong biases from the high levels of tax evasion (between 40 and 55% for nonsalaried activities) (48). In SI Appendix, Appendix C, we explore the potential implications of the large proportion of missing data in the period after 1700 and show that this is not driving our results. The Inquisition was also the driving force behind the expulsion of Spain’s Muslim convert population (“moriscos”) in 1609. The main area affected was Valencia (53). We re-examine the effects of the Inquisition on the income per capita of Valencian municipalities in SI Appendix, Appendix D; adding a control for pre-expulsion morisco population has little impact on the results.

Table 1.

Inquisitorial intensity and modern-day outcomes

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Log GDP p.c. | Religiosity | Education | Trust | |

| Inquisitorial intensity | −0.396*** | 0.445*** | −0.0535** | −0.400*** |

| (−9.58) | (4.83) | (−2.33) | (−2.80) | |

| Log population | 0.000828 | −0.0556*** | 0.0301*** | 0.00389 |

| (0.43) | (−6.78) | (14.55) | (0.29) | |

| Latitude | −0.00213 | 0.0173 | 0.0199*** | 0.0346 |

| (−0.53) | (0.92) | (4.89) | (0.95) | |

| Longitude | −0.000681 | 0.0230* | −0.00137 | 0.0326 |

| (−0.26) | (1.91) | (−0.51) | (1.57) | |

| Ruggedness | −0.00160*** | −0.000807 | 0.0000890 | 0.000955 |

| (−11.95) | (−1.32) | (0.59) | (0.90) | |

| Distance to tribunal | −0.000480*** | −0.0000592 | −0.000179*** | −0.000654 |

| (−9.30) | (−0.28) | (−3.49) | (−1.49) | |

| Distance to river | 0.000302*** | −0.000494** | 0.000180*** | −0.000609 |

| (5.92) | (−2.34) | (3.21) | (−1.64) | |

| −0.000453*** | −0.000437 | −0.000392*** | −0.000253 | |

| (−3.95) | (−0.88) | (−3.44) | (−0.28) | |

| Distance to sea | −0.000187*** | 0.000139 | 0.0000356 | −0.000464 |

| (−4.96) | (0.73) | (0.91) | (−1.32) | |

| Share married | −0.0165 | 0.214*** | 0.000107 | 0.246* |

| (−1.18) | (2.73) | (0.01) | (1.96) | |

| Share upper class | 0.148*** | −0.277** | 0.267*** | 0.200 |

| (6.77) | (−2.51) | (12.28) | (1.30) | |

| Average age | −0.00205*** | 0.0240*** | −0.00320*** | −0.00716 |

| (−3.30) | (6.98) | (−4.84) | (−1.20) | |

| Constant | 10.07*** | 0.247 | −0.412** | −0.863 |

| (64.08) | (0.34) | (−2.57) | (−0.63) | |

| regional FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| N | 2,214 | 2,191 | 2,215 | 976 |

| R 2 | 0.491 | 0.429 | 0.572 | 0.050 |

Coefficients of OLS regressions on inquisitorial intensity with a full set of controls. Dependent variables are the nightlight-based estimate of municipal GDP per capita; the average number of times survey respondents from a given municipality attended religious services in the previous week; the share of the municipal population with a high school degree or higher as of the 2011 census; and average standardized trust in the municipality, calculated from the CIS barometer surveys. Population is the log of the population of the municipality as of the 2011 census. Socioeconomic controls are the average age of the municipal population in the 2011 census, the share of respondents to the CIS barometer surveys that identify as upper-middle class or upper class, and the share of respondents that are married. Geographic controls are longitude and latitude (not reported); ruggedness, calculated using the Nunn and Puga (54) measure averaged over the territory of the municipality; the distance from the centroid of the municipality to the corresponding tribunal city; distance in kilometers to the closest navigable river; distance in kilometers to the closest Roman road; and distance in kilometers to the coastline. Fixed effects are coded for “comunidad autónoma” (NUTS-2 [nomenclature of territorial units of statistics level 2]) regions. t statistics are in parentheses.

P < 0.1, **P < 0.05, and ***P < 0.01.

Correlates and Mechanisms

To understand the mechanisms behind the startling negative impact of the Inquisition on per capita incomes, we compile detailed municipal-level data on religiosity, education, and trust. Results show that higher inquisitorial activity in the past correlates with higher levels of religious observance, lower education, and lower general trust.

The Inquisition’s ostensible goal was to enforce doctrinal orthodoxy and ensure homogeneity of religious beliefs. Is a greater presence of the Inquisition in the past associated with greater religiosity today? We measure religiosity through the frequency of church attendance, obtained from survey data. In column 2 of Table 1, we regress this variable on inquisitorial impact, with the same set of fixed effects and controls as in the economic performance regression. A one-SD increase in inquisition intensity is associated with an increase of between 1.3% and 3.7% in religious service attendance. SI Appendix, Table A.4 shows that results are robust to using different subsets of the control variables, while SI Appendix, Table A.5 does the same, substituting trial frequency as the treatment variable.

Since the Inquisition was particularly suspicious of the educated, literate, and prosperous middle class, its impact on Spain’s cultural, scientific, and intellectual climate was severe [similar effects of government surveillance have been investigated in the context of the Stasi’s legacy in East Germany (14)]. It banned the printing of forbidden books and systematically targeted the richer and more educated parts of society (55, 56). This reduced incentives to become educated, to work hard and become rich, and to think for oneself. Reactions to religious pressure may well have become ingrained in local culture.

This matters because education is a key determinant of economic performance (22); it can be a more reliable predictor than geography or institutions for income levels, both across countries and within them. Its positive effects are well-documented historically: For example, Protestant regions of Prussia in the nineteenth century were richer because literacy rates there were higher (57), areas of South America where the Jesuits—a pro-education order—established missions continue to have higher literacy and output today (58), and the political persecution of intellectuals arguably reduced human capital formation in China (59).

In column 3 of Table 1, we regress the share of population with secondary and tertiary education in Spanish municipalities today on inquisitorial intensity. We find a consistently negative relationship between persecution and educational attainment. Once we control for our standard set of covariates and fixed effects, going from no exposure to the Inquisition to half of all years being affected by persecutions would reduce the share of the population receiving higher education today by 2.7 percentage points, relative to a mean of 47.5 percentage points—a 5.6% relative reduction. SI Appendix, Tables A.6 and A.7 provide full results for alternative specifications and outcome measures.¶

The Inquisition arguably did not only modify individuals’ incentives to become educated. It also changed the way civil society functioned—the extent to which people could cooperate and resolve problems without recourse to the state. The prospect of secret denunciations by acquaintances in localities with a strong inquisitorial presence must have made it harder for residents to engage in communal life, cooperate, and share information—to solve collective action problems that facilitate municipal administration and economic activity (60).

Lower trust as a result of systematic, century-long persecution could be an additional channel for lower incomes. We analyze the relationship between trust and the Inquisition, controlling for a range of potentially confounding variables. The reasons for trust being high or low in some countries or regions but not in others are poorly understood (61). Some scholars have emphasized “amoral familism” driven by family structures, while others have argued that a lack of democratic traditions and weak institutions are important determinants of a lack of trust (20, 62). A more recent research trend emphasizes that trust levels are not predetermined and can be modified by shocks and interventions. For example, areas of Africa more exposed to slave-raiding in the past show markedly lower trust (and income) today (63, 64), while individuals exposed to war seem to be more pro-social and also exhibit higher trust levels (65).

A standard trust question is asked frequently in the Spanish surveys conducted by the CIS: “In general, would you say that people on average can be trusted, or would you say that one can never be too careful?” We analyze responses from more than 26,000 Spaniards interviewed over the period 2006 through 2015. We standardize them by adjusting the response scales from different waves to a mean of zero and SD of one, correct for time and wave fixed effects, and aggregate the answers to the municipal level.

Column 4 in Table 1 presents our main result. A one-SD increase in inquisitorial intensity reduces average municipality-level trust by 0.03 to 0.05 SDs. While the effect may seem small, the limited number of municipalities with trust data—less than 15% of the total—means that attenuation bias is likely. The results are robust to using different subsets of controls (SI Appendix, Table A.8). If we use the second indicator of the Inquisition’s activities, the average number of trials per year in each location, the main effect retains its size and significance in the specification with full controls but is less tightly estimated in others (SI Appendix, Table A.9).

All our results rely on spatial variation. Recent research argues that SEs in persistence studies can be severely understated. We first estimate Moran’s I and find that spatial error correlations are below standard levels of significance for almost all distance thresholds (SI Appendix, Table A.10). Second, we use a recent implementation of the Conley correction to allow for spatial dependence of errors across observations (66).# SI Appendix, Table A.11 shows the SEs for our main results for different cut-offs of spatial dependence. Coefficients are significant at the 1% confidence level in all cases except for education, which is significant at the 5% level for the 100-km cutoff, and at the 10% level for the remaining ones.

Identification

Areas strongly affected by the Inquisition’s activities between the sixteenth and nineteenth century are today poorer, more religious, less educated, and exhibit lower trust. However, the Inquisition may have been more active in towns and cities that were already underperforming by the sixteenth century—places with low trust, low education, high religiosity, and economic problems may have been more prone to collaborating with the Inquisition, for example. If that were the case, our results would reflect the persistence of these characteristics rather than potential effects of religious persecution.

Empirically, the selection issue would ideally be addressed by controlling for indicators of our outcome variables measured before the onset of the Inquisition. Municipal level measures of any of them are not available for the late fifteenth century. Nonetheless, we can use two proxies to make progress.

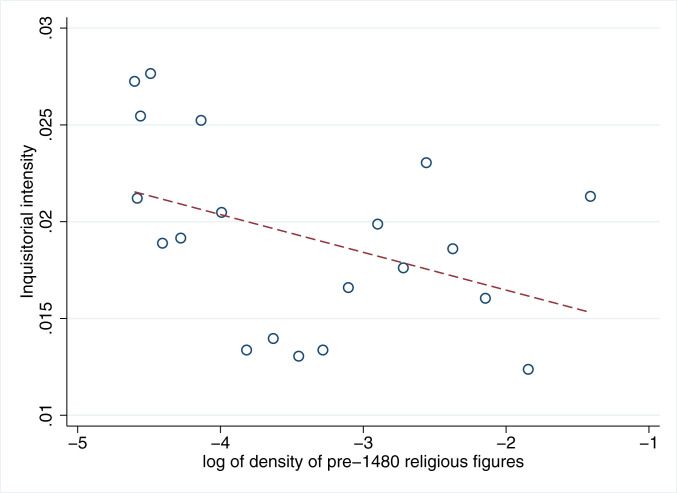

To address the possibility that the Inquisition might have favored locales with high levels of preexisting religiosity, we collect data on pre-Inquisition religious figures from the Spanish Biographical Dictionary (SI Appendix, Appendix E). We then estimate the local density of famous people with strong links to the church and use it to examine whether inquisitorial intensity was systematically higher in places that were more religious pre-1480. Our data suggests the opposite—places with greater inquisitorial intensity had a lower density of famous religious individuals (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Inquisitorial intensity and density of religious individuals pre-1480.

A second concern is that the Inquisition could have been attracted to poorer areas. Standard histories of the Inquisition suggest this is unlikely. The Inquisition was self-financing. It had to confiscate property and impose fines to pay for its expenses and the salaries of inquisitors. While its mission was to persecute heresy, it had strong incentives to look for it in richer places.‖ Its early focus on persecuting Jews and later Protestants led it to target populations with higher levels of education (56).

To rule out issues of reverse causation in the relationship between inquisitorial intensity and economic performance, we can use indicators of municipal wealth from the Catastro de Ensenada, a comprehensive economic census conducted in the 1750s in the Crown of Castile, conducted at the level of the population nucleus.** While the Catastro dates from the mid-eighteenth century, one of its questions targeted a manifestation of wealth that can be reliably tied to the early sixteenth century: hospitals. The early 1500s saw a large wave of creation and consolidation of all sorts of public assistance institutions into proper hospitals, spurred by a decree issued in the Cortes of Toledo in 1525 (69–71). The vast majority of hospitals surveyed in the Catastro date back to this period, when the Inquisition was still in its infancy. Largely geared to care for the poor and for out-of-towners who fell ill and had no other place to stay, hospitals were credited with reducing the number of destitute people living and dying on the streets (72, 73). They required a substantial upfront investment and continuing maintenance expenditures. Municipalities with a hospital in our sample had an average population of 775 households in the 1528 census and were predominantly in rural areas. While some large hospitals in capital cities were endowed by prelates or ecclesiastical institutions, most institutions in our sample were small operations with just a handful of beds, funded from municipal sources and civic groups. Their presence thus reflects both local wealth in the early sixteenth century as well as a measure of social capital (74, 75).††

We code the presence of hospitals for all 710 Castilian municipalities that are also part of the CIS barometer sample.‡‡ Inquisitorial intensity was five times higher in places with hospitals, and the difference is highly significant (SI Appendix, Fig. A.4). The result is robust to controlling for the standard set of covariates and fixed effects as well as for a measure of sixteenth century population (SI Appendix, Table A.12).§§

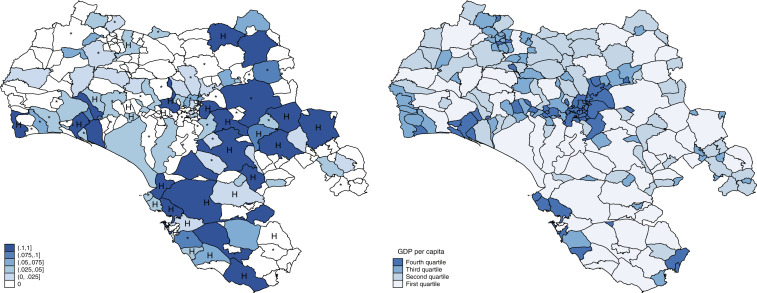

Next, we repeat our main empirical analysis, adding a control for early modern wealth as proxied by hospitals. Fig. 4 illustrates the basic pattern for the case of the tribunal of Seville. The presence of a hospital is strongly correlated with more inquisitorial persecution. Those same municipalities today have much lower incomes than their population would predict.

Fig. 4.

Inquisitorial intensity and income per capita by municipality (Tribunal of Seville). (Left) Inquisitorial intensity. (Right) Nightlight-based GDP per capita. H denotes the presence of at least one early modern hospital in a municipality belonging to our sample of the Catastro de Ensenada. Asterisks mark municipalities in our sample with no hospitals.

Modern economic performance remains negatively associated with inquisitorial impact after controlling for historical measures of wealth, but the coefficient declines in size by one-third. This rules out the possibility that our estimated negative effect of Inquisitorial persecution on incomes reflects the Inquisition targeting poorer areas in the first place. In Panel A of Table 2, we add our control for historical wealth (number of hospitals) to the regressions with income, religiosity, education, and trust as outcome variables. The coefficients on inquisition intensity in the education and trust regressions are broadly comparable to our baseline results in both size and significance. The coefficient in the religiosity regression, however, falls by about half. Including the historical measure of wealth nonetheless shuts down one potential channel of endogeneity and confirms the robustness of our results.

Table 2.

Identification—OLS controlling for historical wealth and CEM estimates

| Log GDP per capita | Religiosity | Share higher education | Standardized trust | |

| Panel A: OLS | ||||

| Inquisitorial intensity | −0.268*** | 0.247* | −0.0713** | −0.474** |

| (−5.10) | (1.79) | (−2.31) | (−2.29) | |

| N | 546 | 545 | 546 | 526 |

| R2 | 0.437 | 0.336 | 0.676 | 0.075 |

| Panel B: CEM | ||||

| Inquisitorial intensity | −0.422*** | 0.316** | −0.121*** | −0.721*** |

| (−7.72) | (2.25) | (−3.52) | (−3.59) | |

| N | 1,336 | 1,324 | 1,337 | 582 |

| R2 | 0.513 | 0.422 | 0.569 | 0.100 |

Panel A: OLS estimation. Dependent variables are as in Table 1. Specifications are shown with a full set of controls including population size, hospital presence, geographic and socioeconomic controls. Panel B: CEM estimates, matching for population today, population in 1528, latitude, longitude, ruggedness, distance to river, and distance to the sea. t statistics in parentheses. *P < 0.1, **P < 0.05, and ***P < 0.01.

Next, we use coarsened exact matching to strengthen our argument that we identify a strong link between religious persecution and lower incomes, education, and trust today. This also helps to address potential issues of imbalance. CEM estimates can demonstrate the strength of a treatment’s impact (76). The CEM estimator picks control observations for each treated unit, ensuring (approximate) covariate balance. Instead of matching observations precisely, CEM estimation involves coarsening covariates to ensure balance of treated and untreated observations. In Panel B, we match municipalities with either above or below median inquisitorial intensity based on their modern-day and historical (1528) population, latitude, longitude, and distance to the sea and to a river.¶¶ Since not all treated municipalities can be matched to an untreated town, the number of observations compared with Table 1 declines. All effects remain large and significant. For religiosity, the estimated impact of persecution declines under CEM compared with OLS but remains significant. For trust, GDP, and education, it grows in size.

One common critique of persistence studies is the “compression of history”—modern-day outcome variables are regressed on indicators of past events, which often occurred centuries earlier (77), with no intervening steps. We can show that in our case, there is evidence of the Inquisition’s impact almost immediately after its abolition. Between 1833 and 1876, Spain suffered from a series of internal conflicts known as the Carlist Wars. The Carlist movement disputed the legitimacy of the ruling branch of the Bourbon dynasty. Carlist supporters were ultra-conservative and highly religious. In SI Appendix, Appendix F, we use granular data from Catalonia, Valencia, and the Balearic Islands to show that the presence of Carlist community organizations (“cercles”) and the share of active Carlist supporters in the population is well-predicted by inquisitorial persecution between 1480 and 1834 (78, 79). This strongly suggests that the Inquisition’s effects were visible immediately after its abolition.

Conclusion

There are major differences in income and wealth across the globe today. Many of these correlate with attitudes and beliefs, which appear to have “deep historical roots,” with differences perpetuating themselves (20, 33, 64, 80, 81). This begs the question of how attitudes diverge in the first place. Do they reflect cultural, ethnic and linguistic differences since prehistoric times or are they driven by human agency in the form of shocks, interventions, and decisions?

In this paper, we focus on a highly repressive institution—the Spanish Inquisition. The Inquisition combined religious persecution with an early state-sponsored form of “totalitarian” control, scrutinizing and controlling every aspect of everyday life, from eating habits to dress code, reading matter, and topics of conversation often with grave consequences over a 350-y period. Relying mostly on accusations and evidence by local informers and members of an individual’s social network, the Inquisition was ideally suited to reduce social capital and imbue citizens with a culture of mistrust and low ambition. Areas where the Inquisition persecuted more citizens are markedly poorer today. We also present evidence that the mechanism behind the long-term detrimental impact of the Inquisition operated through lower trust and education. While we cannot establish that these relationships are causal in a strict sense, historical indicators of religiosity and wealth show that the areas targeted by the Inquisition were not poor or particularly religious in the early modern period.

The negative effect of the Inquisition suggests that adverse shocks at a critical juncture can trap societies in permanently low equilibria, in which high local conflict, low education, and limited trust lead to low income with the risk of undermining social capital and trust still further (82).## While many studies have demonstrated persistence—a link between a modern-day outcome and historical variables, based on geographical variation—few have been able to pin down a mechanism responsible for history’s long shadows (58, 64). Our study contributes to this literature by linking the persistent effects of the Inquisition to modern-day economic performance, showing intermediate outcomes for trust and education.

In this way, we also contribute to the broader literature on the causes of underdevelopment in Southern Europe. Lower incomes and lower trust have been attributed by anthropologists to “amoral familism” (61). Our findings imply that differences in trust and economic performance in Spain today can be directly traced back to religious persecution. Our study has only examined the Spanish Inquisition’s effect in its heartland. However, the Inquisition also operated in Southern Italy and throughout Spanish America. Inquisitorial practices were also instituted throughout the Portuguese Empire and the Papal States. All of these areas today show relatively low education, lower incomes, and less generalized trust. Similar mechanisms to the ones documented in our study may well be at work in these places, affecting the lives of hundreds of millions to this day.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Gustav Henningsen and Gunnar W. Knutsen, without whose collaboration on the EMID this project would not have been possible. For helpful comments, we thank Martha Bailey, Sascha Becker, Roland Benabou, Jeanet Bentzen, Jean-Pierre Dedieu, David Green, Matthew Jackson, Marit Rehavi, Martín Rossi, Jared Rubin, Carlos Santiago Caballero, Felipe Valencia Caicedo, and seminar participants at Harvard, Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR), York, Australian National University (ANU), CEMFI, Carlos III, Universidad de Barcelona, Universidad Torcuato Di Tella (UTDT), Bank of Spain, and Universidad de San Andrés (UdeSA). Research assistance from David González Agudo, Tuomas Kaari, Milena Khalil, Ignacio Sánchez Ayuso, Víctor Saldarriaga, Colin Spear, James Godlonton, Ana Vargas Martínez, and Germán Vega Acuña is gratefully acknowledged. All errors are ours. M.D., J.V.-R., and H.-J.V. acknowledge support from Humanities and Social Sciences Research Council of Canada Grant 435-2015-0285. M.D. acknowledges support from the Canada Excellence Research Chair awarded to Dr. Erik Snowberg in Data Intensive Methods in Economics.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. J.M. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

*With about 135,000 trials conducted over its life, the inquisition averaged some 380 trials per year for all of Spain, or about 16 trials per municipality during three and a half centuries. The unconditional probability of any individual being actually prosecuted was therefore quite small. As the Spanish theologian Francisco Pena commented in this guide for inquisitors: “... the main purpose of the trial and execution is... to achieve the public good and put fear into others” (32).

†Survivorship bias, normally a concern in analysis with substantial missing data, can be largely ruled out in our case. While many tribunal archives did not survive the end of the Inquisition, the majority of our data comes from the “relaciones de causas.” These annual reports were compiled by each tribunal and immediately sent to Madrid, where they were kept in the central archive of the Holy Office. They were not at risk for destruction in the local archives and do not reflect the quality of local record-keeping. While many of them have not survived, this is due to the vagaries of archival preservation in one central location and is uncorrelated with events in regional tribunals.

‡GDP proper is only compiled at the provincial level. Municipal GDP estimates by the National Institute of Statistics are based on income tax returns. These estimates cover only 36% of Spanish municipalities, excluding those with less than 1,000 inhabitants. They are also based on a tax that features a 40 to 55% level of evasion for non-salaried activities (48).

§Reestimating column 1 of Table 1 with population weights gives a coefficient of −0.1579 for inquisitorial intensity. Together with the population-weighted mean impact, 0.2634, this implies a €811 reduction in GDP per capita.

¶SI Appendix, Table A.7 explores the robustness of the relationship to using trial frequency as an impact measure. The coefficient for trial frequency is insignificant in the specification with full controls but regains its significance if the percentage of the population with high school diplomas is used as a dependent variable instead. This suggests an interaction with large cities, where most university graduates live. Once the most populous 10% of municipalities are excluded (population > 30,000), the coefficient in the main specification regains its size and significance.

‖The hypothesis that the motivations of inquisitorial activity were primarily financial was advanced by Llorente, who wrote during the waning days of the Inquisition (68). Kamen has argued forcefully against this view (32). We do not need to take a stand on the Inquisition’s central motive; for our purposes, it is enough that between two localities with similar probability of yielding suspects, the Inquisition directed its attention first to the richer one.

**Digital images of the original responses to the main questionnaire of the Catastro de Ensenada are available online at http://pares.mcu.es/Catastro/.

††The information in the Catastro de Ensenada, like other fiscal surveys, is often suspected of being subject to underreporting. Using hospitals as a measure of wealth circumvents this problem. Hospitals were difficult or impossible to hide, and respondents would likely not have thought that declaring the presence of a hospital in their town would result in higher fiscal pressure.

‡‡The various waves of the CIS barometer surveys contain trust data for 1,148 municipalities. Of these, 438 belong to the historical kingdom of Aragon and hence were not covered in the Catastro. For the remainder 710, we collected data from each population nucleus, aggregating the data at the level of the modern-day municipal boundaries.

§§In some of the specifications in SI Appendix, Table A.12, we control for the number of households reported in the 1528 census of commoners (“censo de los pecheros”) to allow for the possibility that hospitals may simply have reflected a larger population. Because the 1528 census only contains information for the Crown of Castile, only counts commoners, and is known to be fraught with underreporting, we use it cautiously.

¶¶For example, CEM creates 14 different strata for distance to the sea. It will then only match a treated town in one of these strata to another town in the same distance stratum. Overall, the algorithm creates 2,855 combinations of different strata, of which 924 can be matched.

##The opposite is also possible. Valencia Caicedo shows this for the case of an intervention that enhanced human capital exogenously (58).

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2022881118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

The analysis dataset and replication package for this article is available at OpenICPSR (https://doi.org/10.3886/E143781V1) (34). Survey data from the Centre for Sociological Studies is provided at the municipal level of aggregation per confidentiality requirements.

References

- 1.United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, “2018 Annual Report” (USCIRF, Washington, DC, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris S., The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Reason (W. W. Norton & Company, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hitchens C., God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything (McClelland & Stewart, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becker S. O., Rubin J., Woessmann L., “Religion in economic history: A survey” in Handbook of Historical Economics (Academic Press, London, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norenzayan A., Big Gods: How Religion Transformed Cooperation and Conflict (Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber M., The Protestant Ethic and the” Spirit” of Capitalism (Scribner, New York, 1958). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulz J. F., Bahrami-Rad D., Beauchamp J. P., Henrich J., The Church, intensive kinship, and global psychological variation. Science 366, eaau5141 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benabou R., Ticchi D., Vindigni A., Forbidden fruits: The political economy of science, religion, and growth. National Bureau of Economic Research [Preprint] (2015). 10.3386/w21105 (Accessed 11 August 2021). [DOI]

- 9.Barro R. J., McCleary R. M., Religion and Economic Growth across Countries. Am. Sociol. Rev. 68, 760 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saxonberg S., Pre-Modernity, Totalitarianism and the Non-Banality of Evil: A Comparison of Germany, Spain, Sweden and France (Springer, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Squicciarini M., Devotion and development: Religiosity, education, and economic progress in 19th-century France. Am. Econ. Rev. 11, 3454–3491 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hornung E., Immigration and the diffusion of technology: The Huguenot diaspora in Prussia. Am. Econ. Rev. 104, 84–122 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson N. D., Koyama M., Persecution and Toleration: The Long Road to Religious Freedom (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lichter A., Löffler M., Siegloch S., The long-term costs of government surveillance: Insights from stasi spying in East Germany. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 19, 741–789 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawachi I., Kennedy B. P., Lochner K., Prothrow-Stith D., Social capital, income inequality, and mortality. Am. J. Public Health 87, 1491–1498 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rothstein B., The Quality of Government: Corruption, Social Trust, and Inequality in International Perspective (University of Chicago Press, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bjørnskov C., The happy few: Cross-country evidence on social capital and life satisfaction. Kyklos 56, 3–16 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennelly B., O’Shea E., Garvey E., Social capital, life expectancy and mortality: A cross-national examination. Soc. Sci. Med. 56, 2367–2377 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knack S., Keefer P., Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. Q. J. Econ. 112, 1251–1288 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guiso L., Sapienza P., Zingales L., Long term persistence. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 14, 1401–1436 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Besley T., Persson T., The origins of state capacity: Property rights, taxation, and politics. Am. Econ. Rev. 99, 1218–1244 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gennaioli N., La Porta R., Lopez-de-Silanes F., Shleifer A., Human capital and regional development. Q. J. Econ. 128, 105–164 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Netanyahu B., The Origins of the Inquisition in Fifteenth-Century Spain (New York Review of Books, New York, ed. 2, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rawlings H., The Spanish Inquisition (Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas W., “The metamorphosis of the Spanish Inquisition, 1520–1648” in A Companion to Heresy Inquisitions (Brill, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019), pp. 198–227. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haliczer S., Inquisition and Society in the Kingdom of Valencia, 1478-1834 (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1990). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vidal-Robert J., War and Inquisition: Repression in Early Modern Spain (CAGE Online Working Paper Series, Department of Economics, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dedieu J.-P., L’Inquisition et le Droit: Analyse formelle de la procédure inquisitoriale en cause de foi. Melanges Casa Velazquez 23, 227–251 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landes D. S., The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some Are So Rich and Some So Poor (W. W. Norton & Company, 1999). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abellán J. L., “La persistencia de la mentalidad inquisitorial en la vida y cultura española contemporánea, y la teoría de las dos Españas” in Inquisición Española y Mentalidad Inquisitorial, Alcalá A., Ed. (Ariel, Barcelona, 1984), pp. 542–554. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perez J., The Spanish Inquisition: A History (Yale University Press, New Haven, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamen H., The Spanish Inquisition: A Historical Revision (Yale University Press, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nunn N., The historical roots of economic development. Science 367, eaaz9986 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drelichman M., Vidal-Robert J., Voth H.-J., Replication: The long run effects of religious persecution: Evidence from the Spanish Inquisition. OpenICPSR. 10.3886/E143781V1. Deposited 26 June 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Contreras J., Dedieu J.-P., Geografía de la Inquisición Española: La formación de los distritos (1470-1820). Hispania XL, 37–93 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henningsen G., “The Database of the Spanish Inquisition. The “realciones de causas” project revisited” in Vorträge zur Justizforschung. Geschichte und Theorie, Mohnhaupt H., Simon D., Eds. (Vittorio Klosterman, Frankfurt am Main, 1993), pp. 43–85. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Putnam R., Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (Simon & Schuster, New York, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Early Modern Inquisition Database. https://emid.h.uib.no/. Accessed 1 October 2016.

- 39.Contreras J., Henningsen G., “Fourty-four thousand cases of the Spanish Inquisition (1540-1700): Analysis of a historical data bank” in The Inquisition in Early Modern Europe: Studies on Sources and Methods, Henningsen G., Tedeschi J., Eds. (Northern Illinois University Press, DeKalb, IL, 1986), pp. 100–129. [Google Scholar]

- 40.García Cárcel R., Origenes de la Inquisicion Española. El Tribunal de Valencia. 1478-1530 (Península, Madrid, 1976). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blázquez Miguel J., Catálogo de procesos inquisitoriales del Tribunal de Corte. Revista de la Inquisición 3, 205–257 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blázquez Miguel J., Catálogo de los procesos inquisitoriales del Tribunal del Santo Oficio de Murcia. Murgetana 74, 5–109 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blázquez Miguel J., El tribunal de la Inquisición en Murcia (Academia Alfonso X el Sabio, Madrid, 1986). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blázquez Miguel J., Catálogo de los procesos inquisitoriales del Tribunal del Santo Oficio de Barcelona. Espacio, Tiempo y Forma, Serie IV, H. Moderna 3, 11–158 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gracia Boix R., “Autos de fe y causas de la Inquisición de Córdoba” in Colección de Textos para la Historia de Córdoba (Diputación Provincial de Córdoba, 1983), vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pérez Ramírez D., Catálogo del Archivo de la Inquisición de Cuenca (Fundación Universitaria Española, Madrid, 1982). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carrasco R., “Cuantificar las causas de fe” in El Primer Siglo de la Inquisición Española, Cruselles J. M., Ed. (Publicacions de la Universitat de València, Valencia, 2013), pp. 409–430. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Domínguez Barrero F., López Laborda J., Rodrigo Sauco F., El hueco que deja el diablo: una estimación del fraude en el IRPF con microdatos tributarios. Revista de Economía Aplicada XXIII, 81–102 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Doll C. N. H., Muller J.-P., Morley J. G., Mapping regional economic activity from night-time light satellite imagery. Ecol. Econ. 57, 75–92 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Henderson J. V., Storeygard A., Weil D. N., Measuring economic growth from outer space. Am. Econ. Rev. 102, 994–1028 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Michalopoulos S., Papaioannou E., Pre-colonial ethnic institutions and contemporary African development. Econometrica 81, 113–152 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hodler R., Raschky P. A., Regional favoritism. Q. J. Econ. 129, 995–1033 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chaney E., Hornbeck R., Economic dynamics in the Malthusian era: Evidence from the 1609 Spanish expulsion of the Moriscos. Econ. J. (Lond.) 126, 1404–1440 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nunn N., Puga D., Ruggedness: The blessing of bad geography in Africa. Rev. Econ. Stat. 94, 20–36 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Becker S. O., Pino F. J., Vidal-Robert J., “Freedom of the Press? Catholic Censorship during the Counter-Reformation” (Warwick Economics Research Papers No. 1356, Warwick Economics, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Juif D., Baten J., Pérez-Artés M. C., Numeracy of religious minorities in Spain and Portugal during the inquisition era. Rev Hist Econ. 38, 147–184 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Becker S. O., Woessmann L., Was Weber wrong? A human capital theory of protestant economic history. Q. J. Econ. 124, 531–596 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Valencia Caicedo F., The mission: Human capital transmission, economic persistence and culture in South America. Q. J. Econ. 134, 507–556 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koyama M., Xue M., The literary inquisition: The persecution of intellectuals and human capital accumulation in China. SSRN [Preprint] (2015). 10.2139/ssrn.2563609 (Accessed 11 August 2021). [DOI]

- 60.Putnam R. D., Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. J. Democracy 6, 65–78 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Edward B., The moral basis of a backward society. Glencoe 111, 85 (1958). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tabellini G., The scope of cooperation: Normes and incentives. Q. J. Econ. 123, 905–950 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nunn N., The long-term effects of Africa’s slave trades. Q. J. Econ. 123, 139–176 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nunn N., Wantchekon L., The slave trade and the origins of mistrust in Africa. Am. Econ. Rev. 101, 3221–3252 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bauer M., et al., Can war foster cooperation? J. Econ. Perspect. 30, 249–274 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Colella F., Lalive R., Orcan S., Thoenig M., Inference with Arbitrary Clustering (IZA Institute of Labor Economics, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kelly M., The standard errors of persistence. SSRN [Preprint] (2019). 10.2139/ssrn.3398303 (Accessed 3 August 2021). [DOI]

- 68.Llorente J. A., Historia Crítica de la Inquisición (Imprenta del Censor, 1822). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Martínez Martín A. F., El Hospital de la Purísima Concepción de Tunja, 1553-1835 (Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia, Tunja, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 70.García Oro J., Portela Silva M. J., Felipe II y el problema hospitalario: Reforma y patronato. Cuad. Hist. Mod. 25, 87–124 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 71.García Barreño P. R., “Evolución del Hospital” in II Encuentro Hispanoamericano de Historia ce las Ciencias (Ediciones Informatizadas, Madrid, 1990), pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pérez Álvarez M. J., Los pacientes del “Hospital de paisanos” de Zamora en el siglo XVIII. Asclepio 66, p038 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zamorano Rodríguez M. L., El Hospital de San Juan Bautista de Toledo Durante el Siglo XVI (Instituto provincial de investigaciones y estudios toledanos, Toledo, 1997). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barceló Prats J., Comelles Esteban J. M., La economía política de los hospitales en la Cataluña moderna. Asclepio 68, 127 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Solà Colomer X., Petits hospitals rurals: Caritat, misèria i supervivència en els segles XVI i XVII. Alguns exemples de pobles de la Garrotxa i la Selva. Annals del Patronat d’Estu- dis Històrics d’Olot i Comarca 27, 99–134 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Iacus S. M., King G., Porro G., Causal inference without balance checking: Coarsened exact matching. Polit. Anal. 20, 1–24 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Austin G., The ‘reversal of fortune’ thesis and the compression of history: Perspectives from African and comparative economic history. J. Int. Dev. 20, 996–1027 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 78.Toledano Gonzalez L. F., “Antiliberalisme i guerra civil a Catalunya. El moviment Carli davant de la revolucio democratica i la tercera guerra carlina, 1868-1876,” Doctoral dissertation, Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain (1999).

- 79.de Riquer B., Cassassas J., Història. Política, societat i cultura dels Països Catalans (Enciclopedia Catalana, Barcelona, 1996). https://www.enciclopedia.cat/materia/historia?page=1604. Accessed 1 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Voigtländer N., Voth H.-J., Persecution perpetuated: The medieval origins of anti-semitic violence in Nazi Germany. Q. J. Econ. 127, 1339–1392 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 81.Inglehart R., The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles among Western Publics (Princeton University Press, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 82.Acemoglu D., Robinson J. A., The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty (Penguin, 2019). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The analysis dataset and replication package for this article is available at OpenICPSR (https://doi.org/10.3886/E143781V1) (34). Survey data from the Centre for Sociological Studies is provided at the municipal level of aggregation per confidentiality requirements.