Abstract

This brief report highlights the impact of the COVID-19 restrictions on the utilization of Victim Advocacy Agencies’ (VAAs’) services across Pennsylvania, using VAA utilization data from 2019–2020. VAA utilization data in this report were collected from 2019–2020 by the Pennsylvania Coalition Against Rape (PCAR). VAA utilization data were anchored to COVID-19 restriction timelines, defined by the Pennsylvania Office of the Governor. For each month, a percent change in VAA utilization (e.g., Jan 2020 utilization compared to Jan 2019 utilization) was calculated. A one-way ANOVA was run to assess whether the association between restriction phase and percent change in overall VAA utilization from 2019 to 2020 was statistically significant. A substantial decrease in VAA utilization was observed once lockdown restrictions were enacted, as well as a sustained decrease in utilization between 2019 and 2020. When restrictions were eased, an increase in service utilization was noted. This pattern of findings held for the three variables assessed: hotline utilization, new client, and medical accompaniments for FREs per month. The one-way ANOVA confirmed a statistically significant decrease in overall VAA utilization when comparing the most severe COVID-19 related restrictions to both pre-COVID and less severe restrictions. A variety of barriers (e.g., financial instability, loss of childcare, technology access, chronic physical proximity to abuser, hospital visitation restrictions, fears of contracting the virus) may result in decreased utilization of VAA services. Future research should investigate the relevance of potential causal mechanisms behind VAA utilization to help inform intervention approaches.

Keywords: COVID-19, Sexual assault, Domestic violence, Victim advocacy, Utilization of care

Introduction

In March 2020, many countries enacted lockdown measures to slow the spread of COVID-19. While necessary to curb illness and death, the repercussions of these measures resulted in stress, financial instability, and limited resources, all of which can increase risk for violence in the home (Jarnecke & Flanagan, 2020). Early data has confirmed that interpersonal violence including sexual assault and domestic violence, has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic (Campbell, 2020; Gosangi et al., 2020). This brief report focuses on another potential consequence of lockdowns: decreased utilization of victim advocacy services for victims of interpersonal violence.

Victim advocacy agencies (VAA) that provide support to victims of sexual assault and domestic violence offer services such as counseling, legal and medical advocacy, shelter, and connection to community resources. Having support following interpersonal violence can lead to positive healing trajectories for victims (Howard et al., 2003; Sylaska & Edwards, 2014; Trabold et al., 2020; Ullman, 1996). Agencies also support 24/7 crisis hotlines which can be a first point of contact between victim and VAA. Hotlines provide crisis counseling and connection to advocacy services.

Many VAAs that traditionally provide face-to-face services shifted to remote or telehealth services once COVID-19 lockdown measures were enacted. These changes had the potential to either increase or decrease utilization of VAA during the lockdowns. Service utilization could increase through telehealth by decreasing barriers associated with travel (Fryer et al., 2020). Alternatively, concerns about privacy when the abuser resides with the victim, or hospital policies limiting victim advocates’ ability to accompany sexual assault victims during examinations, may result in decreased service utilization (Barbara et al., 2020; Jarnecke & Flanagan, 2020).

Limited evidence from Europe has reported decreased utilization of VAAs during the initial lockdowns (Barbara et al., 2020). The United States has reported mixed results for domestic violence-related police and hotline calls through April 2020, with some cities showing call-related signals of increased domestic violence concerns and others seeing no change or decreases in domestic violence-related calls (Lee, 2020; Tolan, 2020). Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANEs), nurses trained to provide Forensic Rape Exams (FRE), have reported decreases in FREs performed during the lockdown periods of March and April 2020 compared to the year prior (Stahl, 2020). It is important to understand how VAA utilization is impacted by pandemic-related restrictions so solutions can be developed to prevent decreased access or utilization of services when measures must be taken that limit face-to-face interaction. The purpose of this brief report is to highlight the impact of the COVID-19 restrictions on the utilization of VAAs across Pennsylvania using VAA utilization data from 2019–2020.

Methods

Data in this report were collected from 2019–2020 by the Pennsylvania Coalition Against Rape (PCAR). PCAR provides funding, training, and support for VAAs that serve those who experience sexual assault across the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. PCAR-supported VAAs are either sexual-assault specific agencies or dual agencies; those that serve individuals who experience sexual assault and/or domestic violence. VAAs that only serve victims of domestic violence are not affiliated with PCAR and therefore were not included in this study. PCAR collects aggregate, deidentified data from its affiliated agencies to examine service utilization. As these data are aggregate and not identifiable, PCAR was able to provide the authors with 2019–2020 utilization data to analyze the impact of COVID-19 on VAA utilization. Analysis of these data were deemed exempt by the university’s Institutional Review Board.

Data Collection

Victim Advocacy Agencies

Data were collected from the 49 VAAs that cover all 67 counties in Pennsylvania for sexual assault-related services. Of those centers, 33 are considered “dual centers”, providing services to both victims of domestic violence and sexual assault. Data from the dual centers included data from individuals experiencing sexual assault and/or domestic violence whereas the sexual assault-specific agencies provide data from individuals experiencing sexual assault.

Variables

Utilization

The number of hotline calls per month includes number of unique calls to each VAA’s crisis hotline per month. The number of new clients per month includes all clients receiving services for the first time at a VAA. A client is any child or adult victim as well as any family members who receive services. Number of FREs per month includes when a victim advocate joins a victim at the hospital and a FRE is performed.

COVID-19 Restrictions

Timelines of COVID-related restrictions were defined by the Pennsylvania Office of the Governor (Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 2020). Counties transitioned into phases at differing time points depending on levels of virus transmission. The restrictions were defined in phases: Red, Yellow, Green, and Targeted Restrictions. The Red Phase was the most restrictive with stay-at-home orders in place, followed by the Yellow Phase which included aggressive mitigation but allowed schools and certain business to open at reduced capacity. The Green Phase was the least restrictive, allowing for greater capacity for gatherings and an increase in the types of businesses that could open, although at reduced capacity. The Targeted Restrictions were in response to a Fall surge in COVID-19 cases and were focused on school closures in areas with high COVID-19 transmission, limiting travel, and mandating teleworking in all circumstances where possible. Table 1 provides detailed definitions and time frames for each restriction level.

Table 1.

COVID-19 State Enacted Restriction Levels for Pennsylvania

| Restriction Level | Definition | Time Frame |

|---|---|---|

| Red Phase |

• Only life sustaining businesses open • Masks required in public spaces • In person school and childcare closed • Stay at home orders in place • Limitations on in person gatherings • Only travel for life-sustaining purposes |

Mid-March 2020 to May 8th, 2020 |

| Yellow Phase |

Changes from Red to Yellow: • Telework where feasible • Certain businesses open at reduced capacity • Schools and childcare opened • Stay at home order changed to aggressive mitigation • Outdoor dining may resume |

May 8th, 2020 through June 5th, 2020 |

| Green Phase |

Changes from Yellow to Green: • Increased size of gatherings • Indoor dining allowed with reduced capacity • Personal care services and fitness facilities opened • Visitation to hospitals may resume at discretion of facility |

May 29th, 2020 through July 3rd, 2020 and lasted until Targeted Restrictions were enacted November 23rd, 2020 |

| Targeted Restrictions |

Changes from Green to Targeted: • Stay at home advisory • Schools in counties with substantial transmission close for two weeks • Telework mandatory unless impossible • Reduction in gatherings, • Limit unnecessary and out of state travel • Indoor dining and fitness facilities closed |

November 23rd, 2020 to the end of 2020 |

Timelines of COVID-related restrictions were defined by the Pennsylvania Office of the Governor. Counties transitioned into phases at differing time points depending on levels of virus transmission

Analysis

Percent change was calculated between months during the initial COVID-19 restrictions and between corresponding months for 2019 and 2020 (i.e., June 2019 and June 2020). Of note, annually on July 1st, PCAR reclassifies all continuing clients as new clients. Thus, the July 2019 and 2020 new client data is inflated with both continuing clients and new clients.

A one-way ANOVA with two levels on the independent variable (restriction phase: Pre-COVID/Green/Targeted, Red/Yellow) was conducted to examine percent change in utilization from 2019 to 2020. There were a limited amount of data represented by this dataset as there were only 36 datapoints representing percent change for each month (e.g., Jan 2020 hotline calls compared to Jan 2019 hotline calls) across the three types of VAA utilization (i.e., hotline calls, new clients, medical accompaniments for FREs per month). Therefore, a decision was made to collapse Pre-COVID, Green Phase, and Targeted Restrictions Phases of the pandemic into one group, and Red Phase and Yellow Phase into another group. Functionally, phases of the pandemic were dichotomized into least restrictive (e.g., Pre-COVID/Green Phase/Targeted Restrictions Phases) and most restrictive (e.g., Red/Yellow Phases) and compare the percent change in utilization of Victim Advocacy Agencies’(VAAs’) services from 2019 to 2020 across these two levels of restrictions. In addition to dichotomizing the restriction phase, we collapsed data across hotline calls, medical accompaniments, and new client percent change values to create an overall utilization value to provide more stable statistical estimates of association.

Results

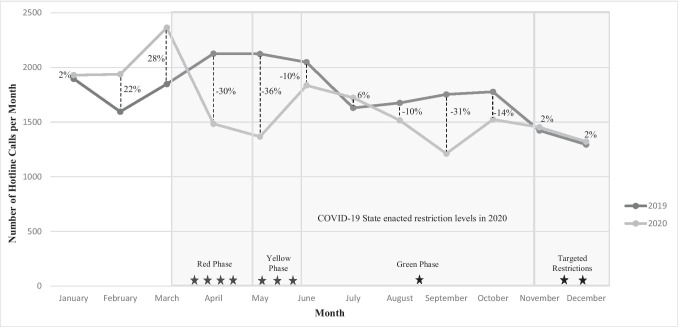

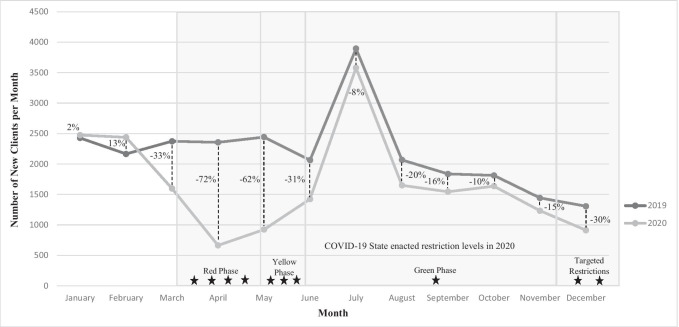

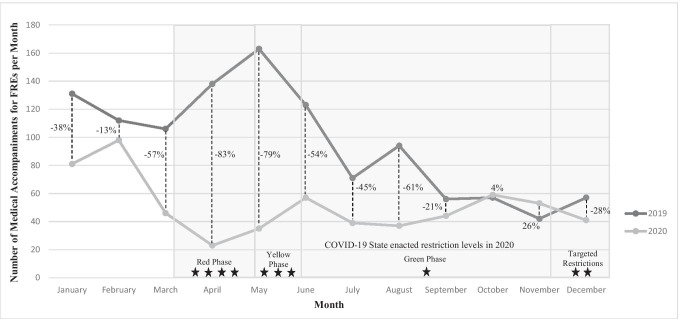

Findings represent data from the 49 VAAs across Pennsylvania from 2019 to 2020. Figure 1 represents the number of hotline calls per month. There was a 37% drop in calls from March to April 2020 when restrictions began. During April and May 2020 hotline utilization was 30% and 36% lower than April and May 2019, respectively. As restrictions eased in June 2020, hotline utilization increased 34%, with only 10% fewer calls compared to June 2019. The average number of hotline calls per month in 2020 across all months was 7% lower than 2019 levels. Similar findings were noted for the number of new clients per month (see Fig. 2); the number of new clients dropped 58% from March to April 2020. The number of new clients per month were 33%, 72%, and 62% lower compared to the corresponding 2019 months of March, April, and May, respectively. While new clients increased by 54% in June 2020, utilization was still 31% lower compared to June 2019. The average number of new clients per month across all months in 2020 was 23% lower than 2019 levels. Figure 3 represents the number of medical accompaniments for FREs per month. There was a 50% drop in medical accompaniments from March to April 2020. Medical accompaniments for FREs in March, April, and May 2020 were 57%, 83%, and 79% lower compared to their corresponding months in 2019, respectively. While medical accompaniments increased by 63% in June 2020, they were still 54% lower than in June 2019. The average number of medical accompaniments for FREs across all months in 2020 was 47% lower than 2019 levels.

Fig. 1.

Monthly Differences in Hotlines Calls to Victim Advocacy Agenices in Pennsylvania between 2019 to 2020, with Corresponding State-Enacted COVID-19 Restrictions. Legend. Dotted lines = percent change between 2019 and 2020 for each month. July 2019 and July 2020 numbers are inflated as continuing and new clients are counted as new clients in July. Number of ★ represents severity of restrictions. Counties transitioned into phases at differing time points depending on levels of virus transmission. Red phase (March 15th- May 8th, 2020) = Stay at home orders, only life sustaining businesses open, schools and childcare closed, masks required in all public spaces. Yellow phase (May 8th—June 5th, 2020) = Stay at home order lifted but aggressive mitigation and must limit gathering sizes, telecommute when feasible, businesses open with limited capacity and safety orders in place, childcare and schools opened. Green Phase (May 29th-November 23rd, 2020) = Increased size of gatherings allowed, indoor dining resumed at reduced capacity, fitness facilities opened. Targeted (November 23rd, 2020-Jan 4th, 2021) = Stay at home advisory, schools in counties with substantial transmission closed for two weeks, telework mandatory unless impossible, reduction in indoor and outdoor gatherings, limit unnecessary and out of state travel, and indoor dining and fitness facilities closed

Fig. 2.

Monthly Differences in Medical Accompaniments for Forensic Rape Exams (FRE) for Victim Advocacy Agencies in Pennsylvania between 2019 to 2020, with Corresponding State-Enacted COVID-19 Restrictions. Legend. Dotted lines = percent change between 2019 and 2020 for each month. July 2019 and July 2020 numbers are inflated as continuing and new clients are counted as new clients in July. Number of ★ represents severity of restrictions. Counties transitioned into phases at differing time points depending on levels of virus transmission. Red phase (March 15th- May 8th, 2020) = Stay at home orders, only life sustaining businesses open, schools and childcare closed, masks required in all public spaces. Yellow phase (May 8th—June 5th, 2020) = Stay at home order lifted but aggressive mitigation and must limit gathering sizes, telecommute when feasible, businesses open with limited capacity and safety orders in place, childcare and schools opened. Green Phase (May 29th-November 23rd, 2020) = Increased size of gatherings allowed, indoor dining resumed at reduced capacity, fitness facilities opened. Targeted (November 23rd, 2020-Jan 4th, 2021) = Stay at home advisory, schools in counties with substantial transmission closed for two weeks, telework mandatory unless impossible, reduction in indoor and outdoor gatherings, limit unnecessary and out of state travel, and indoor dining and fitness facilities closed

Fig. 3.

Monthly Differences in Medical Accompaniments for Forensic Rape Exams (FRE) for Victim Advocacy Agenices in Pennsylvania between 2019 to 2020, with Corresponding State-Enacted COVID-19 Restrictions. Legend. Dotted lines = percent change between 2019 and 2020 for each month. Number of ★ represents severity of restrictions. Counties transitioned into phases at differing time points depending on levels of virus transmission. Red phase (March 15th- May 8th, 2020) = Stay at home orders, only life sustaining businesses open, schools and childcare closed, masks required in all public spaces. Yellow phase (May 8th—June 5th, 2020) = Stay at home order lifted but aggressive mitigation and must limit gathering sizes, telecommute when feasible, businesses open with limited capacity and safety orders in place, childcare and schools opened. Green Phase (May 29th-November 23rd, 2020) = Increased size of gatherings allowed, indoor dining resumed at reduced capacity, fitness facilities opened. Targeted (November 23rd, 2020-Jan 4th, 2021) = Stay at home advisory, schools in counties with substantial transmission closed for two weeks, telework mandatory unless impossible, reduction in indoor and outdoor gatherings, limit unnecessary and out of state travel, and indoor dining and fitness facilities closed

Results of the one-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of restriction phase on percent change in overall utilization of VAA services from 2019 to 2020, F (1, 34) = 6.59, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.36, with larger percent changes from 2019 to 2020 during Red and Yellow Phase restrictions (M(SD) = -60.33 (22.42)) than pre-COVID, Green Phase, and Targeted Restrictions Phases (M(SD) = -14.60 (23.41)).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine VAA utilization throughout the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. The findings reveal a statistically significant decrease in VAA utilization that corresponds to the initiation of the most severe lockdown restrictions (i.e., Red and Yellow Phases) between 2019 and 2020. The difference in utilization during the Red and Yellow Phase restrictions between 2019 and 2020 is troubling, as decreased utilization does not necessarily reflect decreased violence (Gosangi et al., 2020). Early COVID-19 data shows that interpersonal violence is still occurring (Campbell, 2020; Gosangi et al., 2020; Lee, 2020; Tolan, 2020). Increased injuries due to interpersonal violence have been seen during the pandemic compared to interpersonal violence related injuries in 2019 (Gosangi et al., 2020). Given the prevalence of interpersonal violence during COVID-19, the deviation in service utilization seen in this study is likely associated with additional and substantial barriers to seeking and accessing care during COVID-19.

Fear of leaving the home or pandemic-related stress such as financial instability, health concerns, and loss of childcare, can make it challenging to prioritize accessing help. While VAAs offer services through phone or video, those needing help may not have the technology required to receive that care (Saunders, 2020). Many victims of violence live with their abuser, making it hard to find safe space or time away from an abuser to receive phone counseling. Hospital visitor restrictions can prevent advocates from providing accompaniment during FREs. Fear of contracting COVID-19 may prevent victims from seeking care at hospitals. Across the U.S. there was a 42% drop in overall Emergency Department visits from March to April 2020 compared to March to April 2019 (Hartnett et al., 2020).

The percentage change between 2019 and 2020 during Green and Targeted Restriction Phases were smaller in magnitude compared to the change during Red and Yellow Phases. This may reflect the notion that individuals and systems (e.g., survivors, hospitals, and advocates) began to adjust to new ways of operating in a world of COVID-19-related restrictions. Research is needed to understand factors that drive decreased utilization of VAAs in a pandemic, especially as rates of violence are stable, if not increased (Campbell, 2020; Gosangi et al., 2020). By understanding these factors, system changes, such as ensuring equitable access to telehealth platforms for VAAs and their clients or increased funding for VAAs to offer a robust 24/7 counseling and advocacy response, can be implemented when public health or other restrictions in utilization occur. In situations where a victim is isolated at home with an abuser, developing a safety plan on how to reach the victim (e.g., identifying the best time or method to reach a victim, storing the contact as a non-descript name on your phone, have a trusted friend relay messages to the victim from the VAA) or utilizing text message-based counseling may decrease some barriers. Because lockdown measures have varied throughout the pandemic, a continued analysis of VAA data paired with COVID-19 epidemiologic data can provide a more nuanced understanding of how rising or falling COVID-19 case counts and tightening or easing of restrictions may impact victim advocacy utilization.

A few limitations of this study are worth noting. The first is a potential problem endemic to many administrative databases; namely, the variability in the quality of the data collected across a variety of different agencies. There is reason, however, to expect that these data are reliable, given the fluctuation observed from month-to-month both pre- and post-COVID, as well as the fact that these data are utilized by the governing body (i.e., PCAR) to determine funding allocations to VAAs, leaving a standing incentive to accurately report the data. Another limitation is that this study was not able to include data from stand-alone domestic violence agencies, which prevented a more complete picture of utilization for those experiencing interpersonal violence. Including PCAR data with singular domestic violence agencies and comparing to other states that had differing levels of virus circulation and restrictions would allow for enhanced understanding of the impact of COVID-19 cases and mitigation efforts on VAA utilization.

Purposeful funding for VAAs is needed to support the promotion of effective methods to reach victims of violence during restrictions in the provision of care. Funding could support telehealth, additional staff to create a robust 24/7 response to provide counseling during non-business hours, social media outreach campaigns, or even provide cellphones or wireless internet cards to decrease technology barriers. Encouraging hospitals to access telehealth or develop protocols to safely allow victim advocates to provide accompaniments to FREs can increase victims’ connection to advocacy services. Ongoing communication to victims of violence that services are still available and victim advocates will continue to be a safe space for support is warranted to increase awareness of services. Finally, high-quality multi-faceted data collection on the quality of service-provision through VAAs will further the field’s ability to detect challenges in service-provision and test potential solutions so that VAA services can be continuously accessible to all, especially in future public health emergencies.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Miller Hoffman and Lou Ann Williams from the Pennsylvania Coalition Against Rape for their hard work in providing us with this valuable victim advocacy data.

Author Contributions

E.N.W contributed to study design, data analysis and interpretation, figure development, and writing. S.M. contributed to study design, data interpretation, figure development, and writing. C.R. contributed to data analysis and interpretation, figure development, and writing.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- COVID-19, lockdown, and intimate partner violence: Some data from an Italian service and suggestions for future approaches. Journal of Women’s Health, 29(10), 1239–1242. 10.1089/jwh.2020.8590. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Campbell AM. An increasing risk of family violence during the Covid-19 pandemic: Strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Science International: Reports. 2020;2:100089. doi: 10.1016/j.fsir.2020.100089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. (2020). Process to reopen Pennsylvania. Retrieved from https://www.governor.pa.gov/process-to-reopen-pennsylvania/.

- Fryer K, Delgado A, Foti T, Reid CN, Marshall J. Implementation of obstetric telehealth during COVID-19 and beyond. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2020;24(9):1104–1110. doi: 10.1007/s10995-020-02967-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosangi, B., Park, H., Thomas, R., Gujrathi, R., Bay, C. P., Raja, A. S., … Khurana, B. (2020). Exacerbation of physical intimate partner violence during COVID-19 lockdown. Radiology, 202866. 10.1148/radiol.2020202866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hartnett KP, Kite-Powell A, DeVies J, Coletta MA, Boehmer TK, Adjemian J, Gundlapalli AV. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Emergency Department visits — United States, January 1, 2019–May 30, 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2020;69(23):699–704. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6923e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard A, Riger S, Campbell R, Wasco S. Counseling services for battered women: A comparison of outcomes for physical and sexual assault survivors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18(7):717–734. doi: 10.1177/0886260503253230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarnecke AM, Flanagan JC. Staying safe during COVID-19: How a pandemic can escalate risk for intimate partner violence and what can be done to provide individuals with resources and support. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2020;12(S1):S202. doi: 10.1037/tra0000688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M. (2020). Visits to New York City’s domestic violence website surged amid coronavirus pandemic. Retrieved from CNN website: https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/07/us/nyc-domestic-violence-website-surging/index.html.

- Stahl, A. (2020). How COVID-19 is affecting assault survivors seeking care . Retrieved February 24, 2021, from The Appeal website: https://theappeal.org/how-covid-19-is-affecting-assault-survivors-seeking-care/.

- Tolan, C. (2020). Some cities see jumps in domestic violence during the pandemic. Retrieved from CNN website: https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/04/us/domestic-violence-coronavirus-calls-cases-increase-invs/index.html.

- Trabold N, McMahon J, Alsobrooks S, Whitney S, Mittal M. A systematic review of intimate partner violence interventions: State of the field and implications for practitioners. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2020;21(2):311–325. doi: 10.1177/1524838018767934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, K. (2020). Experiences of sex workers during lockdown.https://scotlandinlockdown.co.uk/2020/12/01/experiences-of-sex-workers-during-lockdown/ .

- Sylaska KM, Edwards KM. Disclosure of intimate partner violence to informal social support network members: A review of the literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2014;15(1):3–21. doi: 10.1177/1524838013496335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE. Social reactions, coping strategies, and self-blame attributions in adjustment to sexual assault. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1996;20(4):505–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1996.tb00319.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]