Abstract

Purpose:

We investigated if targeting chromatin stability through a combination of the curaxin CBL0137 with the histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, panobinostat, constitutes an effective multimodal treatment for high-risk neuroblastoma.

Experimental Design:

The effects of the drug combination on cancer growth were examined in vitro and in animal models of MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma. The molecular mechanisms of action were analyzed by multiple techniques including whole transcriptome profiling, immune deconvolution analysis, immunofluorescence, flow cytometry, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, assays to assess cell growth and apoptosis, and a range of cell-based reporter systems to examine histone eviction, heterochromatin transcription, and chromatin compaction.

Results:

The combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat enhanced nucleosome destabilization, induced an interferon response, inhibited DNA damage repair, and synergistically suppressed cancer cell growth. Similar synergistic effects were observed when combining CBL0137 with other HDAC inhibitors. The CBL0137/panobinostat combination significantly delayed cancer progression in xenograft models of poor outcome high-risk neuroblastoma. Complete tumor regression was achieved in the transgenic Th-MYCN neuroblastoma model which was accompanied by induction of a type I interferon and immune response. Tumor transplantation experiments further confirmed that the presence of a competent adaptive immune system component allowed the exploitation of the full potential of the drug combination.

Conclusions:

The combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat is effective and well-tolerated in preclinical models of aggressive high-risk neuroblastoma, warranting further preclinical and clinical investigation in other pediatric cancers. Based on its potential to boost interferon and immune responses in cancer models, the drug combination holds promising potential for addition to immunotherapies.

Keywords: curaxin, HDAC inhibitor, chromatin destabilization, interferon, neuroblastoma

Introduction

Neuroblastoma is the most common extracranial solid tumor in children (1). It is a group of heterogeneous embryonal tumors that arise from organs with neural crest origin such as adrenal glands and sympathetic ganglia. Based on the patients’ age, histology, and tumor staging, neuroblastoma is stratified into low, intermediate, and high-risk groups. High-risk neuroblastoma comprises half of newly diagnosed cases and is frequently characterized by MYCN amplification, which is a strong predictor of poor prognosis (1,2). Current treatments for high-risk neuroblastoma include high doses of chemotherapy, surgery, radiotherapy, myeloablation and stem cell transplant, retinoid therapy, and immunotherapy. However, despite this intensive multimodal regimen, more than 50% of high-risk neuroblastoma patients die within five years post diagnosis. Even with achieving initial remission post-treatment, therapy resistance and early relapse are common in these high-risk patients (3). Moreover, conventional cytotoxic drugs, which still comprise the first-line treatment for neuroblastoma, have detrimental long-term health effects including treatment-induced secondary tumors, cardiac and neurological toxicity, and infertility (4-6). Development of more efficacious and safer drugs for high-risk neuroblastoma thereby remains a high unmet need.

CBL0137 is a non-genotoxic anti-cancer drug belonging to a family of small molecules called curaxins (7,8). It is currently in phase 1 adult clinical trials for advanced melanoma or sarcoma (NCT03727789), and metastatic or unresectable advanced solid neoplasms (NCT01905228). Our group and others have demonstrated that CBL0137, either as a monotherapy or in combination with standard-of-care chemotherapeutic agents, significantly delays cancer progression in several high-risk childhood cancer models, including MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma, and aggressive forms of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (9-11).

CBL0137 exerts its anti-cancer effect through a novel mechanism of action. By intercalating into DNA and interfering with DNA–histone interactions, the drug induces a genome-wide nucleosome destabilization, or “chromatin damage”, without causing DNA damage such as nucleotide alterations or breaks (12-14). This chromatin damage promotes dysregulation of cellular transcriptional and replication programs, ultimately leading to cell death (14). Moreover, nucleosome destabilization induced by CBL0137 increases heterochromatin transcription, stimulating a double-stranded RNA-induced interferon response called Transcription of Repeats Activates INterferon (TRAIN) in tumors (10,13). CBL0137 also acts as an indirect inhibitor of histone chaperone Facilitator of Chromatin Transcription (FACT), trapping FACT onto DNA (i.e. c-trapping) (7,9,12,15). This mediates an array of downstream effects, including p53 activation, NFκB suppression, as well as inhibition of DNA damage repair, all of which restrict cancer progression (7).

Inhibitors of histone deacetylases (HDACs) represent another group of compounds that affect chromatin stability (reviewed in (16)). Panobinostat is a pan-HDAC inhibitor which, through increasing histone acetylation levels, loosens nucleosome structure and decondenses chromatin (16). In addition, the drug induces DNA damage and enhances anti-tumor immunity (17). Panobinostat is an FDA-approved HDAC inhibitor for multiple myeloma and has demonstrated efficacy in a wide range of preclinical pediatric cancer models including high-risk neuroblastoma (18-20). Currently, it is also in early phase trials for hematological (NCT00723203) and solid (NORTH Trial by ANZCHOG) childhood malignancies including neuroblastoma, with previous phase I trials showing good tolerability of the drug in pediatric patients (21,22).

Based on their differing mechanisms of action in destabilizing chromatin, we hypothesized that CBL0137 could synergize with panobinostat. Herein we observed enhanced efficacy of the combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat in animal models of high-risk neuroblastoma. Remarkably, this therapeutic enhancement is significantly more pronounced in an immunocompetent setting and associated with an induction of a type I interferon response and heightened immune responses.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Reagents

CBL0137 was provided by Incuron, Inc. Panobinostat, entinostat (MS-275), and SAHA (vorinostat) were purchased from Sapphire Bioscience Pty Ltd. (Redfern, NSW, Australia), Selleck Chem, and Cayman Chemical, respectively.

Cell lines, cell culture and cell-based assays

All cell lines used in this study are mycoplasma free (mycoplasma testing every six months) and have been authenticated using STR profiling. The patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model COG-N-424x was obtained from the Childhood Cancer Repository, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center in Lubbock, TX, USA. The culturing of neuroblastoma cell lines SK-N-BE(2)-C (referred to as BE(2)-C), KELLY, SH-SY5Y, and NH02A cells, and cell-based assays were performed as previously described (23-26). Caspase-3/7 activity was measured using the Invitrogen CellEvent Caspase-3/7 Green Flow Cytometry Assay Kit according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Etoposide-treated cells were included as a positive control. Samples were run on a BD FACSCanto II and analyzed by FlowJo software. Data are represented as percentages of cells positive for caspase 3/7 activity.

Histone eviction, Micrococcal Nuclease and heterochromatin transcription reporter-cell assays

Histone eviction, Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase), and heterochromatin transcription reporter-cell assays were performed as described previously (13,27,28). Generation of HT1080 cell nuclei tagged with mCherry-H1.5 histone and HeLa-TI cells carrying an integrated avian sarcoma genome with silent green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene was reported previously (13,27,28).

DNA damage repair assays

Assays to assess DNA damage repair after panobinostat treatment (immunoblotting for γH2AX and RPA, immunofluorescence for γH2AX/53BP1-positive foci and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for detection of double stranded DNA breaks) were performed as described previously (9).

Live cell imaging

HT1080 6TG cells were a gift from Eric Stanbridge (University of California, Irvine). HT1080 6TG H2B-mCherry and HT1080 6TG BAX/BAK DKO H2B-mCherry cells were derived previously (24). Imaging was performed on a Zeiss Cell Observer SD spinning disk confocal microscope. HT1080 6TG H2B-mCherry and HT1080 6TG BAX/BAK DKO cell lines were imaged using Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) microscopy combined with fluorescent imaging (10% light source intensity of 561 nm laser, 1 × 1 binning, EM gain of 600 and 50% light source intensity of TL LED, 1 × 1 binning, EM gain of 150) using appropriate filter sets, a 40x/0.95 air objective, 16-bit depth, at 37⁰ C, 10 % CO2 and 3 % oxygen. A total of 10 z-stacks (11.25 ¼m) were captured in an image scaled to 170.67 × 170.67 pixels. Images were captured with Zen software using an Evolve Delta (Photometrics) camera, every 6 minutes for up to 3 days. Image analysis and processing were done using Zen software. Two sets of independent experiments were performed. Quantification of nuclear blebbing was done by manual counting of nuclei in a representative image from each treatment group for the same timepoint.

Western blotting

Western blotting experiments were performed as previously described (9,23). The following antibodies were used: anti-γH2AX antibody [3F2] (phospho S139, ab22551, Abcam, Melbourne, VIC, Australia), anti-H3K27ac antibody (06–599, Millipore, North Ryde, NSW, Australia or ab4729, Abcam), anti-pRPA (ser4/8) antibody (A300–245A, Bethyl, Montgomery, TX, USA), anti-cleaved PARP antibody (95415, Cell Signaling Technology, Genesearch, Arundel, QLD, Australia), anti-total PARP antibody (9532, Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-actin (A2066, Sigma) and anti-GAPDH antibody (Sapphire Bioscience) as loading controls.

Colony formation and cytotoxicity assays

Colony and cytotoxicity assays of neuroblastoma cell lines were performed according to previously published methods (9,23). For colony assays, cells were plated at 500 cells/well in 6-well plates, treated with drugs for 72 hours and after an incubation of 10–14 days, colonies were stained and counted. For cytotoxic assays, cells were plated at 5000 cells/well in 96-well plates and treated for 72 hours before addition of resazurin-based dye and reading of fluorescence on a plate reader. Each experiment was performed in triplicate and drug synergy was determined by Chou and Talalay’s median effect equations using CalcuSyn software (Biosoft) as described previously (9,23).

Animal experiments

All animal experimental procedures were approved by the University of New South Wales Animal Care and Ethics Committee according to the Animal Research Act, 1985 (New South Wales, Australia) and the Australian Code for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes (2013).

The Th-MYCN transgenic mouse model of neuroblastoma has been previously described (9,29,30). All experiments utilized only Th-MYCN+/+ mice with 10 mice per treatment group. Treatment was commenced once the tumor reached 5 mm in diameter by palpation and mice were euthanized when the tumor reached 10 mm in diameter, when signs of a thoracic tumor manifested or in the absence of tumor relapse, at 20 weeks of age.

For neuroblastoma xenograft models, female BALB/c nude mice (nu/nu) (BALB/c-Foxn1nu/Arc) at 4–5 weeks of age were purchased from Australian Resources Centre (Canning Vale, WA, Australia) and allowed to acclimatize for one week before subcutaneous inoculation of 5 × 106 BE(2)-C cells in suspension or 1 × 106 COG-N-424x cells in RPMI (Life Technologies, Mulgrave, VIC, Australia) and an equal volume of growth factor reduced Matrigel (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) into the dorsal flank. Each group consisted of 6 mice.

For immunocompromised vs immunocompetent models, neuroblastoma tumors of approximately 1000 mm3 in size were harvested from Th-MYCN+/+ mice, digested, and then pooled to obtain single cell suspensions. These cells were subsequently subcutaneously transplanted into either BALB/c nudes or the wild-type 129/SvJ littermates of Th-MYCN+/+ mice, with 4.8 × 106 tumor cell suspension/mouse in the dorsal flank.

For all subcutaneously implanted tumors, mice were randomized to the treatment groups and treatment started when the tumor reached 100 mm3 in volume, except for the BE(2)-C tumor model for which treatment started at 50 mm3. Tumor size was measured every other day and calculated as 1/2(length × width x depth).

Mice were given CBL0137 intravenously (40 mg/kg, except for xenograft models which were treated with 60 mg/kg, dissolved in 50 mg/mL Captisol) every four days for 8 doses, panobinostat intraperitoneally (5 mg/kg/day, dissolved in 5% PEG400 and 5% Tween80 saline) for 7 days, or the combination. Mice were euthanized when the tumor reached 1000 mm3, or until the end of the holding period if tumor relapse did not occur. Two-sided log-rank tests were performed to determine statistical significance of survival differences between treatment groups. P-values below 0.05 were considered significant.

Whole transcriptome sequencing and analysis

Total RNA-seq libraries were prepared using Illumina’s cBot cluster generation system with TruSeq PE Cluster Generation Kits (Cat. No. PE-401–3001) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Libraries were pooled and sequencing performed in paired-end mode using Illumina NextSeq 500, with approximately 33M reads per sample. Whole transcriptome sequencing and analysis were performed as described previously (31). Single sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) was performed on the gene expression data generated from the whole transcriptome sequencing using the R graphical user interface ssgsea2.0 (https://github.com/broadinstitute/ssGSEA2.0). All RNA-sequencing data are available through GEO Series accession number GSE151689 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE151689).

Immune cell deconvolution analysis

Immune deconvolution analysis was performed using CIBERSORTx to impute cell fractions from whole transcriptome expression profiles against the previously developed LM22 immune cell signature matrix on control mice or mice treated with either CBL0137, panobinostat or the combination (32,33).

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using a Qiagen RNeasy kit and cDNA synthesized using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (BioRad). SYBR green quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) was run and analyzed on BioRad’s CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System with primers described in Supplementary Table S1.

Immunohistochemistry

Slides of 4 ¼m thickness were prepared and hematoxylin & eosin stained as previously described (9).

Immunofluorescence and whole-tumor scanning

Slides of 4 ¼m thickness were prepared and stained as previously described (34). Slides were incubated with primary antibodies against IFIT3 (Millipore ABF1048, 1:100) and Ki67 (Ab16667, Abcam, 1:60), and Alexa Fluor-labelled secondary antibodies (Life technologies). Whole tumor images were scanned using the Aperio FL (Leica Biosystems, USA). Images were analyzed using ImageScope software (Leica Biosystems, USA) and ImageJ. Three tumors were imaged and quantified for each treatment group. For each tumor image, three fixed-size areas were randomly selected, measured, and averaged. Fixed threshold values of each fluorescence channel were used to highlight and quantify area size. DAPI measurement was used for normalization. All the images were quantified using the same set of parameters, and were adjusted for contrast and brightness in the exact same way.

Flow cytometry analysis of immune cells

Tumors were harvested and digested with 20 ¼g/ml type II DNase I (Sigma, D4527) and 1 mg/mL collagenase IV (Worthington LS004186) to obtain single cell suspensions. Spleen and blood samples were processed with red blood cell lysis buffer (1 mM ammonium bicarbonate and 114 mM ammonium chloride). Antibodies (1:100 ratio) and Zombie Aqua™ live/dead dye (1:500 ratio) (Biolegend, 423102) were added to cell suspensions in PBS and incubated for 20 min on ice before flow analysis on BD FACS CantoB. Data were analyzed on FlowJo and represented as percentages of positive cells. Antibodies: FITC rat anti-mouse CD45 (Biolegend, 103108), APC rat anti-mouse CD3 (Biolegend, 100235), PE rat anti-mouse CD4 (Biolegend, 116005), and PE/Cyanine7 rat anti-mouse CD8a (Biolegend, 100721).

LC-MS/MS determination of CBL0137 and panobinostat concentration in plasma and tumor

Neuroblastoma tumors and plasma were collected from Th-MYCN mice and snap frozen for storage. All samples were prepared at the same time for analysis using a methanol extraction procedure. Approximately 100 mg sections of tumor tissue were supplemented by methanol 1:10 (wt:vol) containing 0.1% formic acid and homogenised using a hand held homogeniser. To complete the compound extraction, the sample solutions were rocked overnight at 2–8°C and then centrifuged for 10 minutes at 14000 rpm and 2–8°C to precipitate the homogenised tissue pellet. The supernatant was then separated and diluted 1:4 (vol/vol) with mobile phase A (MPA) and analysed by LC-MS/MS vs. a reagent-matched calibration curve. Plasma samples were prepared by 1:4 (vol/vol) methanol extraction followed by vortexing for 5 minutes. The samples were then centrifuged for 10 minutes at 14000 rpm and 2–8°C to precipitate the proteins and the supernatant was collected. A detailed description of the LC-MS/MS method is provided in Supplementary Methods.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism8 was used for all statistical analyses. Event-free survival curves were compared by two-sided log-rank tests. All data are represented as mean ± SEM. Comparisons of variables between groups were performed by ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons, or unpaired two-tailed T-tests as indicated in figure legends. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

The combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat induces enhanced chromatin destabilization

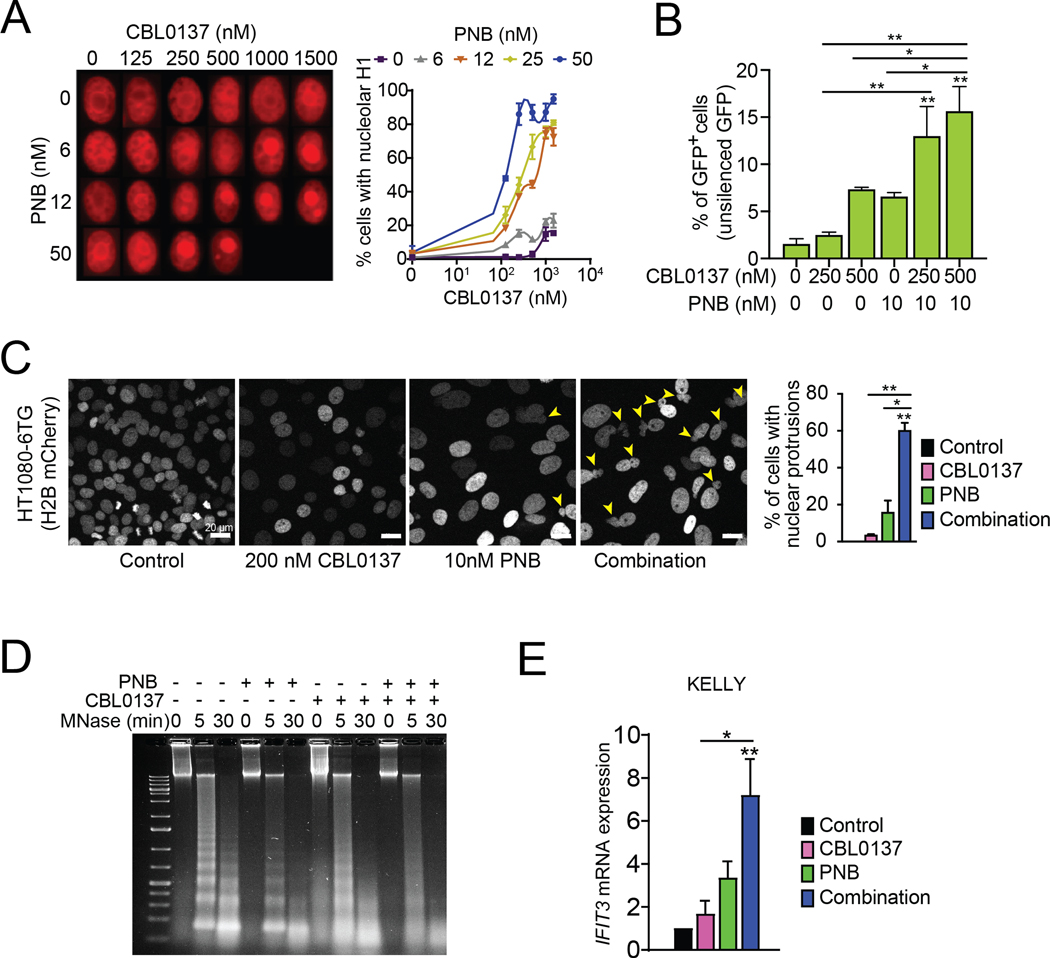

As CBL0137 and panobinostat both promote an open chromatin conformation (1), we postulated that combining these two drugs would induce enhanced nucleosome and chromatin destabilization. Our previous studies showed that eviction of linker histone H1 from the nucleosomes is a highly sensitive measure of nucleosome destabilization (13). We therefore assessed the combined effect of CBL0137 and panobinostat on histone H1 eviction by evaluating the subnuclear localization of H1 in nuclei of HeLa cells overexpressing mCherry-histone H1 (Fig. 1A). H1 lost from chromatin accumulates in nucleoli, which allows easy monitoring of this process in live cells (13). While panobinostat and CBL0137 as single agents induced nucleolar accumulation of histone H1 (mCherry-histone H1, red) in less than 20% of cells at highest applied doses, the combination of both drugs markedly enhanced this effect (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1. The combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat (PNB) induces chromatin destabilization.

A. Fluorescence imaging of HT1080 cell nuclei tagged with mCherry-H1.5 histone after treatment with increasing concentrations of CBL0137 and PNB. Left panel shows representative images of HT1080 cell nuclei at indicated drug concentrations. Right panel shows quantifications of the nucleolar accumulation of mCherry-H1.5 histone. B. Percentages of GFP+ HeLa cells following CBL0137 and PNB treatment. These cells carry a silenced GFP gene in the heterochromatin region; GFP expression indicates activation of heterochromatin transcription. C. Representative fluorescence images of HT1080 6TG-H2B mCherry cells treated with CBL0137 and PNB. Yellow arrowheads indicate nuclei with blebs. Live imaging videos of each treatment can be found in Supplementary Videos (1-4). Right panel shows quantifications of nuclear blebs in C. D. MNase assay on nuclei isolated from human neuroblastoma KELLY cells and treated with CBL0137 (25 ¼M) and/or PNB (50 nM) for 15 min. E. Gene expression of IFIT3 in human neuroblastoma KELLY cells treated with 200 nM CBL0137, 10 nM PNB, or the combination for 72 hr relative to vehicle-treated cells, as determined by qRT-PCR. Bar graphs represent mean +/− SEM of at least three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by One-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01. Statistical data displayed at the top of a bar in the graphs correspond to comparisons with control cells.

Our previous data also demonstrated that nucleosome destabilization induced by CBL0137 results in an increased transcription of silenced heterochromatin regions (13). To determine if concurrent exposure to panobinostat could further enhance this effect, we used HeLa cells carrying an integrated avian sarcoma virus genome containing a green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene of which expression is silenced under basal conditions of chromatin condensation (13,28). Indeed, while CBL0137 dose-dependently increased GFP expression, the combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat doubled the percentage of cells with GFP expression in comparison to cells treated with the single agents (Fig. 1B), confirming that this combination promotes enhanced chromatin destabilization and heterochromatin transcription.

A highly organized chromatin state is essential to maintain structural integrity of the nucleus. Chromatin decompaction and destabilization can lead to morphological aberrations such as nuclear blebbing (35). We assessed if the combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat impacted nuclear structural integrity by live-cell imaging using HT1080 6TG cells expressing H2B-mCherry, which facilitates nuclear visualization (24). While panobinostat caused nuclear blebbing in a small proportion of cells, when treated with the combination, approximately 60% of the cells displayed nuclear protrusions (Fig. 1C, and Supplementary Videos S1-S4). As the HT1080 6TG cells are a p53-mutant line, the observed effect is independent of p53 activation (24). Moreover, a similar percentage of cells with nuclear blebbing was seen in apoptosis-deficient BAX−/−/BAK−/− cells, confirming that the combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat negatively impacted nuclear structural integrity and that this observation was not a direct downstream effect of apoptosis (Supplementary Fig. S1A, S1B).

The combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat induces chromatin destabilization, activates an interferon response, and enhances DNA damage in neuroblastoma cells

To confirm that the combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat enhanced chromatin destabilization in neuroblastoma cells, we performed MNase assays to assess the relative condensation of chromatin in cells after treatment with CBL0137, panobinostat or the combination. As MNase preferentially digests protein-free DNA, the pattern of DNA fragmentation resulting from treatment of cell nuclei is an indicator of relative chromatin condensation. Compared to untreated nuclei, DNA isolated from neuroblastoma cell nuclei treated with either CBL037 or panobinostat as a single agent was digested into smaller fragments more rapidly (Fig. 1D). This effect was even more pronounced upon combined treatment with CBL0137 and panobinostat, with the isolated DNA appearing as a smear without clear laddering. This confirms enhanced chromatin destabilization in neuroblastoma cells treated with the combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat.

Downstream of chromatin destabilization, CBL0137 induces an interferon response in tumor cells (10,13). Panobinostat was also recently shown to activate a type I interferon response in dendritic cells through epigenetic reprogramming (36). To determine whether adding panobinostat to CBL0137 augmented the interferon response in tumor cells, we assessed the effect of the drug combination on expression levels of IFIT3. The expression of this interferon-induced gene was previously shown to be significantly upregulated in cancer cells in vitro and in vivo in response to CBL0137 treatment (10). Adding panobinostat to CBL0137 significantly increased IFIT3 gene expression in neuroblastoma cells compared to treatment with vehicle or CBL0137 alone (Fig. 1E), confirming that the combination enhanced interferon signaling within the tumor cells.

Furthermore, panobinostat treatment has been shown to result in DNA damage accumulation in cancer cells (37), while CBL0137 inhibits repair of DNA damage caused by genotoxic chemotherapy, sensitizing tumor cells to chemotherapy (9). To assess if CBL0137 potentiates the effects of panobinostat via inhibition of the repair of panobinostat-induced DNA damage in high-risk neuroblastoma cells, we examined the extent of DNA repair in a MYCN-amplified, multidrug-resistant neuroblastoma cell line BE(2)-C, post panobinostat-treatment in the presence or absence of CBL0137. Following 20 hours of panobinostat pretreatment and a 20-hour recovery, BE(2)-C neuroblastoma cells were able to spontaneously repair the panobinostat-induced DNA damage as evidenced by a reversal of the panobinostat-induced increase in number of treated BE(2)-C cells with γH2AX and 53BP1 double-positive foci in the nuclei (Fig. 2A). However, upon addition of CBL0137 during the recovery phase, the resolution of γH2AX and 53BP1 double-positive foci was significantly attenuated indicating that the repair of panobinostat-induced DNA damage was prevented by the drug (Fig. 2A). Similarly, phosphorylated RPA and γH2AX levels, as markers of DNA damage, in panobinostat-pretreated BE(2)-C and KELLY neuroblastoma cells returned to baseline levels upon recovery in the absence of CBL0137 (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Fig. S2A and S2B). This effect was diminished when cells recovered in the presence of CBL0137, while H3K27 acetylation levels remained unchanged (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Fig. S2A and S2B). The inhibitory effects of CBL0137 on the repair of panobinostat-induced DNA damage were further confirmed in a pulsed-field gel electrophoresis assay in BE(2)-C cells demonstrating that the presence of CBL0137 during recovery after panobinostat administration attenuated repair of DNA double strand breaks (Fig. 2C, Supplementary Fig. S2C).

Figure 2. The combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat (PNB) promotes DNA damage and synergistically decreases neuroblastoma cell growth.

A. Experimental design (upper panel) for the DNA damage repair assay showing that human neuroblastoma BE(2)-C cells were first treated with PNB for 20h. The drug was then washed out, and cells were subsequently allowed to recover in the absence (0 nM) or presence (100 nM, 200 nM) of CBL0137 for an additional 20h before downstream analyses. Lower panel shows immunofluorescence images of expression of γH2AX (red) and 53BP1 (green) in the presence or absence of CBL0137 post-PNB treatment, with a quantification graph on the right. DAPI (blue) was used for nuclear staining. Right panel shows percentages of cells with more than 5 γH2AX/53BP1 double positive foci in BE(2)-C cells. For each treatment group the number of double positive foci in a total of 50 cells was counted in 3 fields. B. Western blot analysis of phosphorylated (p)RPA, γH2AX, and H3K27Ac in the absence or presence of CBL0137 after PNB pretreatment of BE(2)-C cells. C. Pulse-field gel electrophoresis image showing the repair of PNB-induced DNA double-strand breaks in the presence or absence of CBL0137 during recovery. Representative data of two independent biological assays in BE(2)-C are shown. D. Colony assays conducted in human neuroblastoma KELLY cells. Cells were treated with escalating doses of CBL0137 and/or PNB for 72 hr and then allowed to form colonies for 10 to 14 days. Data were collated from three independent biological assays, and representative images of treatment wells were shown under the graph. The Combination Index (CI) was calculated using CalcuSyn software. CI < 0.9 indicates drug synergy. E. Caspase-3/7 activity in human neuroblastoma KELLY cells treated with 200 nM CBL0137, 10 nM panobinostat or the combination for 72 hr. Data are represented as percentages of cells positive for caspase 3/7 activity (relative to vehicle-control treated cells). F. Western blots showing levels of cleaved (c)PARP in KELLY cells after treatment with 200 nM CBL0137 and 5 nM PNB for 72 hr. Bar graphs represent the mean +/− SEM of at least three independent experiments relative to vehicle-treated cells. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. * P<0.05, *** P<0.001, *** P<0.0001. Statistical data displayed at the top of a bar in the graphs correspond to comparisons with control cells.

The combination of CBL0137 and HDAC inhibitors synergistically inhibits neuroblastoma cell growth

As chromatin stability, suppression of the interferon pathway and repair of DNA damage are critical for cancer cell proliferation, we assessed the downstream effects of the combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat on neuroblastoma cell growth and survival. CBL0137 and panobinostat synergistically reduced colony formation of human and mouse MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma cell lines (Fig. 2D, Supplementary Fig. S3A, S3B). This attenuated tumor cell growth was accompanied by increased caspase-mediated apoptosis induction as indicated by elevated levels of caspase-3/7 activity (Fig. 2E) and enhanced PARP cleavage (Fig. 2F, Supplementary Fig. S3C, S3D), which was preventable by pre-incubation with the pan-caspase inhibitor QVD (Supplementary Fig. S3E).

To confirm that the mechanistic basis of the observed synergy between CBL0137 and panobinostat was dependent on the inhibitory action of panobinostat on HDACs, we tested whether similar synergy was also observed between CBL0137 and other HDAC inhibitors. We observed that CBL0137 synergized with the pan-HDAC inhibitor SAHA as well as with entinostat, an inhibitor of class I HDACs, in colony formation assays with neuroblastoma cells (Supplementary Fig. S4A, S4B). Similarly, CBL0137 combined with entinostat and SAHA induced caspase-mediated apoptosis evidenced by increased levels of caspase-3/7 activity (Supplementary Fig. S4C) and PARP cleavage (Supplementary Fig. S4D). CBL0137 thus synergizes with other HDAC inhibitors in addition to panobinostat, providing further evidence that inhibition of histone deacetylation lies at the mechanistic basis of the detected synergy between CBL0137 and panobinostat.

As one of the important anti-cancer actions of CBL0137 involves inhibition of histone chaperone FACT, we subsequently investigated whether loss of FACT would influence the observed synergy between CBL0137 and panobinostat. We therefore assessed the effect of silencing the expression of SSRP1, the major protein subunit of FACT, on sensitivity of neuroblastoma cells to panobinostat. We observed that panobinostat decreased colony growth to a similar extent in BE(2)-C neuroblastoma cells, irrespective of the presence or absence of SSRP1 silencing, indicating that silencing of FACT alone does not synergize with HDAC inhibition in neuroblastoma cells (Supplementary Fig. S5).

We previously reported on a positive feedback loop between FACT and MYCN signaling in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma and on the particular potency of CBL0137 against neuroblastoma cell lines with high MYCN expression. We also demonstrated that CBL0137 limits MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma tumor growth by decreasing expression levels of the MYCN oncogene, thereby limiting N-MYC signaling, an important oncogenic driver in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma. Similarly, panobinostat was shown to decrease MYCN expression in neuroblastoma models (18). We found that combining CBL0137 and panobinostat further reduced N-MYC protein levels in neuroblastoma cells compared to either agent alone (Supplementary Fig. S6A). As N-MYC is instrumental for the proliferation and survival of MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma cells, the decreased expression of N-MYC is likely to negatively impact neuroblastoma cell proliferation.

To assess whether the combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat also exerted synergistic cytotoxicity against non-MYCN amplified neuroblastoma cells, we performed synergy assays in non-MYCN amplified human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Synergy assays confirmed that CBL0137 and panobinostat were highly synergistic in SH-SY5Y cells (Supplementary Fig. S6B) indicating that synergy between CBL0137 and panobinostat is independent of MYCN gene amplification status. These data are consistent with our finding that the drug combination induces several anti-cancer mechanisms that are independent of N-MYC signaling (Fig. 1, Fig. 2).

Overall, our in vitro data demonstrate that the combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat limited several cancer cell survival pathways and synergistically suppressed cell growth in high-risk neuroblastoma cell lines.

The combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat suppresses tumor progression in high-risk neuroblastoma mouse models

We have previously shown that CBL0137 as a single agent significantly extends survival in preclinical models of MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma (9), and others have demonstrated preclinical efficacy of panobinostat in these models (18). Based on our in vitro data demonstrating synergistic inhibitory effects of the combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat on neuroblastoma cell growth and survival, we hypothesized that in vivo therapeutic enhancement would occur when combining both drugs in preclinical neuroblastoma models.

Athymic nude mice were subcutaneously engrafted with either the drug-refractory neuroblastoma cell line BE(2)-C, or a highly aggressive neuroblastoma patient-derived xenograft line (COG-N-424x), both of which carry MYCN gene amplification (9,38). The combination treatment extended the median survival from 12.4 to 23.7 days in the BE(2)-C model and from 20.6 to 29.9 days in mice bearing COG-N-424x neuroblastoma tumors, corresponding to an extension of survival of 91% and 45% compared to vehicle-treated mice, respectively (Fig. 3A, 3B; Supplementary Table S2). The survival extension induced by the combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat was significantly longer than that achieved for either single agent, demonstrating therapeutic enhancement of both drugs in combination (Fig. 3A, 3B; Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 3. The combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat (PNB) limits tumor progression in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma cell line xenograft and PDX models.

(A) Kaplan-Meier survival plot (top) and tumor growth curve (bottom) of mice engrafted with BE(2)-C neuroblastoma xenografts following treatment with vehicle, CBL0137, PNB, or the combination. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival plot (top) and tumor growth curve (bottom) of mice engrafted with COG-N-424x PDX cells following treatment with vehicle, CBL0137, PNB, or the combination. A tumor volume > 1000 mm3 was defined as endpoint for survival analysis. Growth curves of individual tumors are shown as colored lines. The dotted line in the tumor growth curve plots indicates the tumor burden at endpoint. The solid bar above the survival graphs represents treatment duration for PNB and arrows indicate the CBL0137 treatment regimen. Long-rank test was used to compare survival between treatment groups. P-values comparing survival of control and treatment groups are denoted directly under each graph in the graph legend.

There is clear evidence for an activation of an interferon response in tumors treated with CBL0137 as demonstrated by increased expression of IFIT3 (Supplementary Fig. S7). Moreover, endpoint tumors from mice treated with CBL0137, panobinostat or the combination showed increased presence of necrotic lesions compared to vehicle controls, consistent with these drugs inducing neuroblastoma cell death in vitro (Supplementary Fig. S8).

The combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat induces complete tumor regression in Th-MYCN transgenic neuroblastoma mice

It was recently shown that one of the anti-cancer mechanisms of CBL0137 constitutes the stimulation of anti-tumor immunity downstream of chromatin destabilization and induction of an interferon response (10,13,39). To determine whether the therapeutic enhancement of CBL0137 by addition of panobinostat could be further potentiated in the presence of a fully functioning immune system, we next determined the efficacy of the combination in an immunocompetent transgenic mouse model of MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma.

Th-MYCN transgenic mice spontaneously develop neuroblastomas at three to five weeks of age, and the tumors rapidly progress to maximum tumor burden within five to seven days without therapeutic intervention. In agreement with our findings in vitro, treatment with the CBL0137 and panobinostat combination significantly increased IFIT3 protein levels in vivo (Supplementary Fig. S9A, S9B). Panobinostat as a single agent and combined with CBL0137 augmented histone H3 acetylation levels (Supplementary Fig. S9C), confirming target engagement by both drugs at applied doses in vivo.

While treatment of the Th-MYCN transgenic mice with CBL0137 and panobinostat as single agents significantly extended event-free survival, the combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat produced complete ablation of established neuroblastoma in 100% of the Th-MYCN transgenic mice (Fig. 4A, Supplementary Table S3). None of the mice treated by the combination displayed tumor relapse at the termination of the experiment, whereas tumors progressed to the maximum burden within 60 days post-treatment initiation in all the mice treated with either vehicle, CBL0137, or panobinostat alone, demonstrating the powerful anti-tumor effect of the combination in this model (Fig. 4A, Supplementary Table S3). These results indicate that efficacy of the CBL0137 and panobinostat combination may be augmented by the presence of an intact immune system.

Figure 4. The combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat (PNB) produces complete tumor regression in the immunocompetent Th-MYCN transgenic neuroblastoma model.

A. Kaplan-Meier survival plot of neuroblastoma-bearing Th-MYCN mice following treatment with vehicle, CBL0137, PNB, or the combination. A tumor size > 10 mm in diameter as determined by palpation was defined as the endpoint for survival analysis. Long-rank test was used to compare survival between treatment groups. P-values comparing the control and treatment groups are denoted directly next to each group in the graph legend. B. RNA-seq data displayed in a heatmap showing differential gene expression in transcripts per million (TPM) in tumors harvested from Th-MYCN mice 16 hr post treatment with one dose of vehicle, CBL0137, PNB, or the combination. C. Gene ontology (GO) analyses of the RNA-seq data showing top ten most significantly enriched biological processes in tumors treated with the combination of CBL0137 and PNB. Significantly changed genes (False Discovery Rate (FDR)<0.05) with an absolute fold change (FC) greater than 2 were used for the GO analyses. D. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) plots showing significant enrichment of inflammatory and interferon pathways. NES: normalized enrichment score. E. Gene expression of interferon-related genes in Th-MYCN tumors after a 16 hr treatment with CBL0137, PNB, or the combination. Bar graphs represent mean expression +/− SEM relative to vehicle controls, as determined by qRT-PCR in at least two mice per group. Statistical significance was determined by One-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01. Statistical data displayed at the top of a bar in the graphs correspond to comparisons with the control group.

The combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat induces an interferon response in Th-MYCN transgenic neuroblastoma mice

To confirm that the combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat affected immune pathways in the tumor, whole transcriptome expression profiling (RNA-seq) was performed on tumors from mice treated with a single dose of CBL0137, panobinostat or the combination. The combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat induced a strong alteration in gene expression compared with the control or single-agent treatment groups (Fig. 4B). We observed a highly significant upregulation of multiple pathways associated with immune responses, and downregulation of cell cycle, nucleosome assembly, and cell division pathways (Fig. 4C). In particular, gene sets associated with immune responses and type I interferon were substantially enriched in tumors treated with the combination (Fig. 4D). This was confirmed by ssGSEA analysis showing uniform enrichment of these pathways in individual samples from each treatment group, with a higher level of enrichment in the combination treatment group compared to vehicle and single-agent treatment (Supplementary Fig. S10A). Many genes encoding for cytokines and chemokines are differentially expressed in mice following treatment with the CBL0137 and panobinostat combination by comparison with vehicle-treated mice (Supplementary Table S4). The genes with the most significant and highest fold change in expression (i.e., Ccl12, Ifnb1, Cxcl10, Cxcl11, Isg15, Cxcl9, Ccl5, Ccl7 etc) are all interferon-induced, which is consistent with our finding that the combination induces a robust interferon response. We further validated the upregulation of interferon-regulated genes, including Ifit3, Ifit3b, Ifit1b1, Ccl12, Ccl8 and Slfn4 by qRT-PCR in the neuroblastoma tumors (Fig. 4E). These data together demonstrated a robust interferon response and immune-stimulating effect of the combination compared with either single agent. Conversely, gene sets related to chromatin function were negatively impacted as shown by GSEA and ssGSEA analyses (Supplementary Fig. S10B, S10C). Mki67, Ccnb1, and Cdk4, genes involved in cell proliferation, cell cycle, and chromatin assembly, were significantly downregulated by the combination as demonstrated by qRT-PCR and immunofluorescence of neuroblastoma tumors (Supplementary Fig. S11A-C). Similar changes in expression of genes involved in cell cycle and division pathways were observed in human neuroblastoma cells treated with the combination in vitro (Supplementary Fig. S11D).

Importantly, the observed changes in gene expression upon CBL0137 and panobinostat treatment were confined to the tumor, and were not observed in other non-tumor tissues (liver, lung, and kidney) of treated mice (Supplementary Fig. S12). Moreover, induction of the interferon response genes Ifit3 and Ccl12 in liver, lung, and kidney tissue by either CBL0137 or the combination was at least 5–10 times lower than that in the tumor, while Ki67 was not affected by the drugs in these normal tissues, suggesting the synergy of the combination is tumor-specific.

In line with this, and consistent with our previous findings that CBL0137 accumulates in tumors compared to normal tissues (9), we observed that CBL0137 levels in the Th-MYCN tumors were more than 100 times higher than in plasma and were not affected by addition of panobinostat (Supplementary Fig. S13A). The panobinostat concentration was lower in tumors treated with the combination than in those treated with panobinostat alone, possibly due to decreased uptake by the compromised tumor cells (Supplementary Fig. S13B).

The combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat induces an immune response in Th-MYCN transgenic neuroblastoma mice

To confirm that the combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat activated an immune response, and to study the effects of the drug combination on the immune response within neuroblastoma tumors, we next performed CIBERSORT, a computational method designed to quantify cell fractions from bulk tissue gene expression profiles (RNA-seq data). This approach has been used to characterize tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and accurately estimate the immune composition of tumors (40). CIBERSORT was applied to the RNA-seq data from murine neuroblastoma tumors from Th-MYCN mice treated with vehicle, CBL0137, panobinostat or the combination for 16 hours. Based on this analysis, the combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat significantly increased (4-fold) tumor infiltration by CD45+ lymphocytes while a trend was observed for higher levels of immune infiltration by treatment with either agent alone compared to the vehicle control (Fig. 5A). The drug combination also significantly increased the number of CD4+ T cells, both naïve and memory CD4+ T cells, by comparison with the vehicle control and single agent treatment arms (Fig. 5A), while a trend for higher levels of total CD3+ T cells was also noted for the combination relative to vehicle controls (Supplementary Fig. S14). Whilst no significant changes were observed in amounts of CD8+ T cells, NK cells, B cells or monocytes within the tumor, intratumoral levels of macrophages and dendritic cells were elevated after combination treatment compared to treatment with the vehicle or either agent alone (Supplementary Fig. S14).

Figure 5. The combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat (PNB) activates an immune response that contributes to the efficacy of the drug combination.

A. Analysis of immune cell infiltration in Th-MYCN tumors treated with vehicle, CBL0137, PNB, or the combination for 16 hr as determined by the CIBERSORT deconvolution method. Each dot point represents one tumor. Statistical significance was determined by One-Way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. B. Flow cytometry analysis of CD3+ CD4+ T cells (relative to total number of CD45+ immune cells) in Th-MYCN tumors treated with vehicle, CBL0137, PNB or the combination for 16 hr. Each dot point represents the measurement in one tumor. Statistical significance was determined by One-Way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. C. Schematic of the experiment (top panel). Neuroblastomas developed in Th-MYCN mice were isolated, dissociated, pooled and then subcutaneously (SC) engrafted in either immunocompetent 129/SvJ or immunocompromised Balb/c nude mice. Treatment started when tumor size reached 200 mm3. Bottom panel shows Kaplan-Meier survival curves of immunocompetent mice (left) and immunocompromised mice (right) following treatment with vehicle, CBL0137, PNB, or the combination. CBL0137 was administered i.v. every four days for eight doses; PNB was administered i.p. consecutively for seven days. Timepoints at which mice in each treatment group were culled after reaching the maximum tumor burden (1000 mm3) were used to plot the survival curves. Long-rank test was used to compare survival between treatment groups. P-values comparing the control and treatment groups are denoted directly next to each group in the graph legend. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001.

We subsequently analyzed the composition of the tumor lymphocyte infiltrate (CD45+ cells) by performing flow cytometry on digested Th-MYCN tumors treated with CBL0137, panobinostat or the combination for 16 hours. Consistent with the CIBERSORT analysis, we confirmed that the lymphocyte infiltrate of tumors treated with the combination contained a significantly increased percentage of CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5B). The blood and spleens of animals treated with the combination also contained significantly increased percentages of CD4+ T cells in these tissues compared to vehicle-treated mice, confirming the immune-stimulating effect of the combination (Fig. 5B). Consistent with the CIBERSORT data, flow analysis showed that there was no increase in intratumoral CD8+ cells after treatment with the combination or with either drug alone (Supplementary Fig S15). However, a significant increase in CD8+ T cells was seen in the spleen, but not the blood, after treatment with the combination, suggesting the mounting of a cytotoxic T cell response against the tumor within the spleen at this time point after treatment (Supplementary Fig S15). No significant changes were observed in the proportions of other immune cell subsets within the tumor lymphocyte infiltrate (data not shown).

Taken together, these data indicate that the combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat activates a T cell response in an immunocompetent neuroblastoma model and that this response is associated with complete tumor regression.

Presence of an intact immune system with an adaptive immune component promotes durable tumor regression by the combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat

To provide further evidence that the activation of a T cell response by the combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat contributes to its anti-cancer effects and therapeutic enhancement by comparison with the effect of either treatment alone, we compared the efficacy of the drug combination against neuroblastoma tumours xenografted in immunocompetent versus immunocompromised mouse strains. We subcutaneously transplanted dissociated Th-MYCN tumor cells into either immunodeficient BALB/c nude mice that lack T cells and have a dysfunctional adaptive immune system, or into the immunocompetent 129/SvJ mice that have a fully functioning immune system, and then treated with CBL0137, panobinostat, or the combination (Fig. 5C, Supplementary Fig. S16). Panobinostat treatment displayed a similar efficacy in the immunodeficient and immunocompetent mice. However, CBL0137 and particularly the combination was more effective against tumors engrafted in the immunocompetent mouse strain (Fig. 5C, Supplementary Fig. S16, Supplementary Table S5). All the immunocompetent mice (100%) treated with the combination achieved complete tumor regressions, compared to 50% of the immunodeficient mice in the same treatment group. The immunocompetent mice treated with the combination exhibited complete and durable tumor regression without relapse for up to a year at which point the experiment was terminated. These findings confirm that the combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat has reduced efficacy in an immunodeficient model that lacks T cells and that the presence of a fully functional immune system with an adaptive immune component allows the drug combination to exert its full anti-cancer potential.

Taken together, our study has modeled an effective, previously unexplored, multiagent cancer treatment strategy targeting chromatin stability. Our data demonstrate that upon combining CBL0137 with panobinostat, multiple anti-cancer mechanisms are activated and channeled into two major pathways, culminating in an enhanced direct and indirect inhibition of cancer progression (Fig. 6). More importantly, presence of an intact immune system is shown to be critical in achieving a durable therapy response, indicating that the combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat may regulate key factors in anti-tumor immunity.

Figure 6. Schematic of mechanism of action for the CBL0137 and panobinostat (PNB) combination.

The combination of CBL0137 and PNB inhibits tumor growth via a multi-pronged attack. Chromatin destabilization caused by the combination increases transcription of heterochromatin, leading to activation of an interferon response. The drug combination also stimulates the immune system with activation of an adaptive immune response, increasing tumor-infiltrating and circulating CD4+ T cells, which enhances anti-tumor immunity. Chromatin disassembly and damage compromises DNA repair contributing to DNA damage accumulation, ultimately resulting in decreased proliferation and increased tumor cell death.

Discussion

The identification of safer and cancer-selective multimodal treatment options for high-risk neuroblastoma is urgent. Herein we report on a novel combination of anti-cancer drugs, the curaxin CBL0137 and the HDAC inhibitor panobinostat, which was well-tolerated in several mouse strains and displays enhanced preclinical efficacy in multiple animal models of high-risk neuroblastoma. Mechanistic studies reveal that CBL0137 and panobinostat amplify each other’s effects to accelerate nucleosome disassembly and histone eviction, and this dual targeting of chromatin stability may thus constitute an alternative therapeutic modality for high-risk neuroblastoma.

We propose a model whereby CBL0137 and panobinostat work in tandem to destabilize chromatin, enhance heterochromatin transcription, activate an interferon response and promote DNA damage accumulation in cancer cells, resulting in direct inhibition of cancer cell growth and survival (Fig. 6). A parallel pathway boosts a T cell immune response against the tumors, indirectly limiting cancer progression. The resulting two-pronged attack on cancer cells by the combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat induces complete tumor regressions in an immunocompetent model of MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma, which is dependent on the presence of an adaptive immune component.

The combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat elicits a tumor-specific interferon response and growth suppression that is absent in normal tissues, suggesting a highly targeted anti-tumor effect. The tendency of CBL0137 to accumulate in tumor cells could further mitigate adverse effects even with prolonged treatment. These are ideal properties of a drug candidate for pediatric cancers where severe debilitating side effects from standard multi-modal chemotherapies are a major concern. The combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat thereby presents a clinically viable option for the treatment of high-risk neuroblastoma, providing support for further investigations into targeting chromatin stability as a treatment strategy for other childhood cancers.

Recently, immunotherapies have achieved remarkable results in halting progression of relapsed and refractory cancers that were once considered incurable (41). Based on this initial success, currently available immunotherapeutic regimens are rapidly moving into first-line therapy. However, the efficacy of immunotherapy is hampered by immune-evasion of the tumor and the development of drug resistance. The identification of compounds that can further potentiate current immunotherapies through reprogramming the tumor microenvironment and/or enhancing anti-tumor immunity is therefore highly desirable.

One of the well documented immune evasion mechanisms in solid tumors is the suppression of interferon pathways (42). As CBL0137 has been shown to induce a robust interferon response in tumors, the drug could reactivate innate immune sensing. This is supported by our findings of increased immune pathway engagement upon CBL0137 treatment in our transgenic neuroblastoma model. Combining CBL0137 with the known immunomodulator panobinostat further augmented this effect, and produced durable and complete tumor regression in immunocompetent tumor-bearing mice. Corroborating our findings, other studies have uncovered a strong link between the host immune response and tumor cell chromatin structure and modifications, initiating a wave of clinical and animal studies, in which epigenetic targeting agents are combined with immunotherapies to improve efficacy (reviewed in (43)).

Together, our results suggest that the combination of CBL0137 and panobinostat holds potential as an immunotherapeutic or immunomodulatory approach. Additional work defining the entire spectrum of the pathways of this immune enhancement by the combination offers great promise for designing more effective therapies and identifying biomarkers for patient stratification. Moreover, to further elucidate the clinical potential of the immunomodulatory actions of CBL0137, future combination studies with current immunotherapies such as immune checkpoint inhibitors and CAR-T cells are warranted.

Supplementary Material

Statement of translational relevance.

Despite escalation of treatment intensity in recent years, high-risk neuroblastoma, frequently driven by MYCN amplification, has a survival rate below 50%. Furthermore, the long-term quality of life of survivors is often severely compromised by detrimental consequences of conventional treatments. In light of the high unmet need for more effective and safer treatments for high-risk neuroblastoma, this study proposes the combination of the curaxin CBL0137 with the HDAC inhibitor panobinostat as a novel treatment strategy targeting chromatin stability. Our data demonstrate that the drug combination induces enhanced chromatin destabilization, DNA damage accumulation and synergistic inhibition of cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo. In addition, the combination mediates part of its action through eliciting a type I interferon response and engaging the immune system. Thus, this provides opportunities for the use of this drug combination in the modulation of anti-tumor immunity.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank QIMR Histology Staining Facility, Garvan Histopathology Facility, the Animal Facility at Children’s Cancer Institute, and Ramaciotti Centre for Genomics at UNSW, for providing technical assistance for this project. Scott Page and the Australian Cancer Research Foundation Telomere Analysis Centre at the Children’s Medical Research Institute (CMRI) are thanked for microscopy infrastructure.

L. Xiao and E. Ronca are supported by a grant from Cancer Institute NSW (ECF171127) and philanthropy from Neuroblastoma Australia. K. Somers is supported by funding from the Kids Cancer Alliance (KCA). K. Somers, M. Karsa, A. Bongers and M. Henderson are supported by funding from Tenix Foundation and Anthony Rothe Memorial Trust. D. Carter and L. Zhai are supported by grant (1123235) awarded through the Priority-driven Collaborative Cancer Research Scheme and co-funded by Cancer Australia and The Kids’ Cancer Project. A. O’Connor and A. Cesare is supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (1053195, 1106241, 1104461), and philanthropy from the Goodridge Foundation and Stanford Brown, Inc (Sydney, Australia). M. Haber and M. Norris are supported by grants from NHMRC (APP1132608 and APP1085411), Cancer Institute NSW (14/TPG/1-13), Cancer Council NSW (PG 16-01), Tour de Cure, and Neuroblastoma Australia.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure statement

KVG and AVG are co-authors of patent WO2010/042445 “Carbazol compounds and the therapeutic use of the compounds”. KVG is a recipient of research grants and consulting payments from Incuron, Inc.

References

- 1.Louis CU, Shohet JM. Neuroblastoma: molecular pathogenesis and therapy. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:49–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinto NR, Applebaum MA, Volchenboum SL, Matthay KK, London WB, Ambros PF, et al. Advances in risk classification and treatment strategies for neuroblastoma. JCO. 2015;33:3008–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basta NO, Halliday GC, Makin G, Birch J, Feltbower R, Bown N, et al. Factors associated with recurrence and survival length following relapse in patients with neuroblastoma. Br J Cancer. 2016;115:1048–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen LE, Gordon JH, Popovsky EY, Gunawardene S, Duffey-Lind E, Lehmann LE, et al. Late effects in children treated with intensive multimodal therapy for high-risk neuroblastoma: high incidence of endocrine and growth problems. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49:502–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Applebaum MA, Vaksman Z, Lee SM, Hungate EA, Henderson TO, London WB, et al. Neuroblastoma survivors are at increased risk for second malignancies: A report from the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group Project. Eur J Cancer. 2017;72:177–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman DN, Goodman PJ, Leisenring W, Diller L, Cohn SL, Tonorezos ES, et al. Long term morbidity and mortality among survivors of infant neuroblastoma: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS). JCO. American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2019;37:10051–1. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gasparian AV, Burkhart CA, Purmal AA, Brodsky L, Pal M, Saranadasa M, et al. Curaxins: anticancer compounds that simultaneously suppress NF-κB and activate p53 by targeting FACT. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:95ra74–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burkhart C, Fleyshman D, Kohrn R, Commane M, Garrigan J, Kurbatov V, et al. Curaxin CBL0137 eradicates drug resistant cancer stem cells and potentiates efficacy of gemcitabine in preclinical models of pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget. 2014;5:11038–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter DR, Murray J, Cheung BB, Gamble L, Koach J, Tsang J, et al. Therapeutic targeting of the MYC signal by inhibition of histone chaperone FACT in neuroblastoma. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:312ra176–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Somers K, Kosciolek A, Bongers A, El-Ayoubi A, Karsa M, Mayoh C, et al. Potent antileukemic activity of curaxin CBL0137 against MLL-rearranged leukemia. Int J Cancer. 2020;146:1902–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lock R, Carol H, Maris JM, Kolb EA, Gorlick R, Reynolds CP, et al. Initial testing (stage 1) of the curaxin CBL0137 by the pediatric preclinical testing program. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64:e26263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nesher E, Safina A, Aljahdali I, Portwood S, Wang ES, Koman I, et al. Role of chromatin damage and chromatin trapping of fact in mediating the anticancer cytotoxicity of DNA-binding small-molecule drugs. Cancer Res. 2018;78:1431–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leonova K, Safina A, Nesher E, Sandlesh P, Pratt R, Burkhart C, et al. TRAIN (Transcription of Repeats Activates INterferon) in response to chromatin destabilization induced by small molecules in mammalian cells. eLife. 2018;7:631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurova KV. Chromatin Stability as a Target for Cancer Treatment. Bioessays. 2019;41:e1800141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barone TA, Burkhart CA, Safina A, Haderski G, Gurova KV, Purmal AA, et al. Anticancer drug candidate CBL0137, which inhibits histone chaperone FACT, is efficacious in preclinical orthotopic models of temozolomide-responsive and -resistant glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19:186–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.West AC, Johnstone RW. New and emerging HDAC inhibitors for cancer treatment. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:30–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medon M, Vidacs E, Vervoort SJ, Li J, Jenkins MR, Ramsbottom KM, et al. HDAC inhibitor panobinostat engages host innate immune defenses to promote the tumoricidal effects of trastuzumab in HER2+ tumors. Cancer Res. 2017;77:2594–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waldeck K, Cullinane C, Ardley K, Shortt J, Martin B, Tothill RW, et al. Long term, continuous exposure to panobinostat induces terminal differentiation and long term survival in the TH-MYCN neuroblastoma mouse model. Int J Cancer. 2016;139:194–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hennika T, Hu G, Olaciregui NG, Barton KL, Ehteda A, Chitranjan A, et al. Pre-clinical study of panobinostat in xenograft and genetically engineered murine diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma models. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0169485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wirries A, Jabari S, Jansen EP, Roth S, Figueroa-Juárez E, Wissniowski TT, et al. Panobinostat mediated cell death: a novel therapeutic approach for osteosarcoma. Oncotarget. 2018;9:32997–3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldberg J, Sulis ML, Bender J, Jeha S, Gardner R, Pollard J, et al. A phase I study of panobinostat in children with relapsed and refractory hematologic malignancies. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2020;:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wood PJ, Strong R, McArthur GA, Michael M, Algar E, Muscat A, et al. A phase I study of panobinostat in pediatric patients with refractory solid tumors, including CNS tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2018;82:493–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gamble LD, Purgato S, Murray J, Xiao L, Yu DMT, Hanssen KM, et al. Inhibition of polyamine synthesis and uptake reduces tumor progression and prolongs survival in mouse models of neuroblastoma. Sci Transl Med. American Association for the Advancement of Science; 2019;11:eaau1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masamsetti VP, Low RRJ, Mak KS, O’Connor A, Riffkin CD, Lamm N, et al. Replication stress induces mitotic death through parallel pathways regulated by WAPL and telomere deprotection. Nat Commun. Nature Publishing Group; 2019;10:4224–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng AJ, Cheng NC, Ford J, Smith J, Murray JE, Flemming C, et al. Cell lines from MYCN transgenic murine tumours reflect the molecular and biological characteristics of human neuroblastoma. European Journal of Cancer. 2007;43:1467–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Somers K, Chudakova DA, Middlemiss SMC, Wen VW, Clifton M, Kwek A, et al. CCI-007, a novel small molecule with cytotoxic activity against infant leukemia with MLL rearrangements. Oncotarget. Impact Journals; 2016;7:46067–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Safina A, Cheney P, Pal M, Brodsky L, Ivanov A, Kirsanov K, et al. FACT is a sensor of DNA torsional stress in eukaryotic cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;5:gkw1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poleshko A, Einarson MB, Shalginskikh N, Zhang R, Adams PD, Skalka AM, et al. Identification of a functional network of human epigenetic silencing factors. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:422–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiss WA, Aldape K, Mohapatra G, Feuerstein BG, Bishop JM. Targeted expression of MYCN causes neuroblastoma in transgenic mice. The EMBO Journal. 1997;16:2985–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henderson MJ, Haber M, Porro A, Munoz MA, Iraci N, Xue C, et al. ABCC multidrug transporters in childhood neuroblastoma: clinical and biological effects independent of cytotoxic drug efflux. JNCI. 2011;103:1236–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Somers K, Evans K, Cheung L, Karsa M, Pritchard T, Kosciolek A, et al. Effective targeting of NAMPT in patient-derived xenograft models of high-risk pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. Nature Publishing Group; 2019;125:3977–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, Gentles AJ, Feng W, Xu Y, et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods. Nature Publishing Group; 2015;12:453–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newman AM, Steen CB, Liu CL, Gentles AJ, Chaudhuri AA, Scherer F, et al. Determining cell type abundance and expression from bulk tissues with digital cytometry. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:773–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quek H, Luff J, Cheung K, Kozlov S, Gatei M, Lee CS, et al. A rat model of ataxia-telangiectasia: evidence for a neurodegenerative phenotype. Hum Mol Gen. 2017;26:109–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stephens AD, Liu PZ, Banigan EJ, Almassalha LM, Backman V, Adam SA, et al. Chromatin histone modifications and rigidity affect nuclear morphology independent of lamins. Mol Biol Cell. 2018;29:220–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salmon J, Todorovski I, Vervoort SJ, bioRxiv KS, 2020. Epigenetic reprogramming of plasmacytoid dendritic cells drives type I interferon-dependent differentiation of acute myeloid leukemias for therapeutic benefit. biorxivorg. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Hamamah MA, Alotaibi MR, Ahmad SF, Ansari MA, Attia MSM, Nadeem A, et al. Genetic and epigenetic alterations induced by the small-molecule panobinostat: A mechanistic study at the chromosome and gene levels. DNA Repair (Amst). 2019;78:70–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rokita JL, Rathi KS, Cardenas MF, Upton KA, Jayaseelan J, Cross KL, et al. Genomic Profiling of Childhood Tumor Patient-Derived Xenograft Models to Enable Rational Clinical Trial Design. Cell Reports. 2019;29:1675–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen M, Brackett CM, Burdelya LG, Punnanitinont A, Patnaik SK, Matsuzaki J, et al. Stimulation of an anti-tumor immune response with “chromatin-damaging” therapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2021; doi: 10.1007/s00262-020-02846-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen B, Khodadoust MS, Liu CL, Newman AM, Alizadeh AA. Profiling Tumor Infiltrating Immune Cells with CIBERSORT. Methods Mol Biol. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2018;1711:243–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emens LA, Ascierto PA, Darcy PK, Demaria S, Eggermont AMM, Redmond WL, et al. Cancer immunotherapy: Opportunities and challenges in the rapidly evolving clinical landscape. Eur J Cancer. 2017;81:116–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parker BS, Rautela J, Hertzog PJ. Antitumour actions of interferons: implications for cancer therapy. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2016;16:131–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dunn J, Rao S. Epigenetics and immunotherapy: The current state of play. Mol Immunol. 2017;87:227–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.