Abstract

Objectives

To provide information on systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients’ experiences, satisfaction, and expectations with treatments and examine the association between treatment satisfaction and patient-reported outcomes (PRO).

Methods

A cross-sectional, non-interventional, online survey of US adult patients with SLE was conducted in 2019. The survey consisted of 104 questions about SLE and the following PRO instruments: LupusPRO™, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) Fatigue, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI), an 11-point Worst Pain Numerical Rating scale (NRS), and an 11-point Worst Joint Pain NRS.

Results

Five hundred participants (75% female, 76% White/Caucasian, mean age 42.6 ± 12.7 years, 63% with an associate degree or higher) completed the survey. Most participants were “completely” or “somewhat satisfied” with their treatments, although satisfaction rates were lower for corticosteroids (65%), immunosuppressants (71%), and anti-malarials (55%) than for belimumab (intravenous or subcutaneous) (86%) and rituximab (94%). Treatments were more often considered “burdensome” or “very burdensome” for belimumab (67%) and rituximab (63%) than for corticosteroids (48%), immunosuppressants (49%), and anti-malarials (30%). Pain and productivity assessments supported substantial impairment for the majority of participants, even those who indicated that they were completely satisfied with treatments. The treatment goals most commonly reported as “very important” were reducing fatigue, pain, and the frequency or severity of flares. Three-quarters of participants (76.6%) indicated that their physician’s goals for their therapy matched their own goals “very” or “somewhat closely.” Despite high levels of satisfaction, most participants (63.0%) indicated that their physicians had not asked about their treatment goals during the past 3 months.

Conclusion

SLE patients reported high rates of satisfaction with current therapies despite identifying substantial treatment burdens, residual pain, and fatigue. Reduced fatigue, pain, and flares were the most important treatment goals for these patients.

Keywords: Patient-reported outcomes, Systemic lupus erythematosus, Treatment goals, Treatment satisfaction

Key Summary Points

| SLE is an autoimmune disease, with only one biologic treatment approved in the last 10 years |

| The current study explored experiences, satisfaction, and expectations with treatments and examined the association between treatment satisfaction and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) |

| The most prominent symptoms of SLE were fatigue and pain and important treatment goals were reducing fatigue, pain, and the frequency or severity of flares |

| The SLE population in the US demonstrated a high rate of satisfaction with their current therapies, although satisfaction rates were lower for corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and anti-malarials than for biologic treatment |

| Despite high levels of satisfaction, most participants indicated that their physicians had not asked about their treatment goals during the past 3 months |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.14673216

Introduction

Advances in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) have occurred more slowly than for other autoimmune conditions. The only biologic approved for the treatment of SLE is belimumab, which became available almost a decade ago and is authorized as an add-on therapy to standard of care [1]. Because of the limited use of belimumab, SLE continues to be treated with older, non-SLE specific therapies, including anti-malarials, corticosteroids, and immunosuppressants [2]. Treatment goals of currently available therapies include prevention of organ damage, minimization of drug side effects through reduced dosage or use of glucocorticoids, and improvement of patients’ quality of life [3]. The extent to which the commonly used therapeutic armamentarium reaches these goals and patient satisfaction with these therapies has not been well characterized.

Studies that have assessed treatment satisfaction with routinely used standard of care therapies have generally found a fairly high rate of patient-reported satisfaction. A cross-sectional survey comprising 50 rheumatologists and 99 patients with SLE from the US, performed before the approval of belimumab, found that 79% of physicians were satisfied with their patient’s disease control and that almost 76% of patients were satisfied with their current treatment. Agreement between physician and patient satisfaction was modest, with patients more frequently being more dissatisfied than physicians with the degree of fatigue, pain, joint, and skin symptom control [4]. A more recent survey of physician and patient satisfaction conducted after belimumab became available found that 86% of patients reported being at least “somewhat satisfied” with treatment regimens including belimumab and 78% being at least “somewhat satisfied” with treatment regimens not including belimumab [5]. The main drivers of satisfaction in patients using belimumab were improvement in leisure activities, fatigue, and pain.

In addition to the treatment goals described, more recent initiatives have set out to establish standardized treat-to-target goals in SLE including remission and low disease activity states [6]. Remission and low disease activity are defined based on validated clinician-assessed instruments, such as the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) [7] and the Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA) [8]. Maximum thresholds of glucocorticoid dose are also incorporated in these definitions. Retrospective data suggest that remission and low disease activity are associated with improvements in organ damage, mortality, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [9–10]. However, patient-reported outcomes (PRO) are not included in these treat to target definitions. The discordance between physicians and SLE patients in the importance and prioritization of disease manifestations may also lead to different expectations of remission and low disease activity states, which may also ultimately affect patient satisfaction with therapy [11–12].

The UNVEIL survey, conducted in 2014 in a partnership with the Lupus Foundation of America, examined the burden of SLE for patients and their caregivers in the US [13–14]. In 2019, the partnership conducted a further survey—SLE-Understanding Preferences, Disease Activity, and Treatment Expectations (SLE-UPDATE)—to provide detailed information on patient experiences, satisfaction, and expectations with current SLE treatment. Here, we describe the results of the survey and the association between treatment satisfaction and PROs.

Methods

Study Design

This was a cross-sectional, non-interventional, online survey of adult patients with SLE conducted between October and November 2019 in the US. The study consisted of: (1) a qualitative pilot phase to refine the survey and confirm that the survey content was understood and relevant and (2) a main study phase. This study was approved by a US ethical institutional review board in accordance with local law. Advarra, a US-based institutional review board, reviewed study documents (protocol, informed consent form, and patient survey) prior to completion of any patient data. All participants completed an electronic informed consent form prior to completing the online survey. All data were de-identified and kept confidential in accordance with International Council for Harmonization for Good Clinical Practice.

Participants

Participants were recruited from various sources including: two patient proprietary databases and four patient panels (confirmed as being pre-profiled as having a diagnosis of Lupus) as well as supplementary ad hoc clinician referrals from various geographical locations in the US. Members of patient panels or databases were sent email invitations containing a link to the online survey. Participants were screened for eligibility electronically as part of the survey and were included if they were ≥ 18 years old, had a self-reported clinician diagnosis of SLE, and were able to read, speak, and understand English. Participants were excluded if they reported having cutaneous lupus (subacute or discoid) and/or drug-induced lupus, were currently participating in a clinical trial for SLE, or had any condition that could interfere with their ability to provide consent and participate in the survey. Efforts were made to limit the proportion of patients with self-identified comorbid fibromyalgia or Sjogren’s syndrome.

SLE-UPDATE Survey

A targeted literature review was conducted to gather information on the symptoms of SLE and their impact on the daily lives of patients to support the development of the SLE-UPDATE survey. The survey was developed by: (1) reviewing the items included in previous lupus patient-focused surveys and discussions with the Lupus Foundation of America about the issues important to patients with SLE, (2) the targeted literature review, and (3) expert opinion about key PRO measures. Feedback was obtained from authors on the content of the survey, with recommendations for revisions. The survey went through three rounds of revision before considered final by all authors.

The survey consisted of 104 SLE-related questions on patient demographics, clinical presentation of SLE symptoms, lupus flares, work productivity and career progression, current treatments, treatment goals and expectations, healthcare access, and coverage and reimbursement. For each treatment that the participants were taking, they were asked about their overall satisfaction with the medication, how burdensome the medication was, and reasons for burden, including side effects experienced. In addition, the survey included the following five PRO instruments: LupusPRO™, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT)-Fatigue, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI), Worst Pain Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), and Worst Joint Pain NRS. LupusPRO™ [15] is a 43-item SLE-targeted measure of HRQoL and non-HRQoL over the past 4 weeks that has been validated for SLE assessment in the US [16]. The LupusPRO™ scores range from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating better quality of life. FACIT-Fatigue is a 13-item instrument assessing fatigue, tiredness, and their impact on daily activities and functioning. FACIT-Fatigue scores range from 0–52 with higher scores indicating less fatigue [17]. WPAI:Lupus is a six-item measure covering absenteeism, presenteeism, work productivity loss, and activity impairment over the past 7 days. WPAI:Lupus scores range from 0–100 with higher scores indicating worse productivity [18]. The Worst Pain and Worst Joint Pain NRSs are 11-point (0–10) scales of worst pain and worst joint pain over the past 24 h, with higher scores indicating higher levels of pain [19]. The FACIT-Fatigue, WPAI: Lupus, and Lupus PRO measures [15, 18, 20–22] included in the SLE-UPDATE Survey have been previously validated for use in the SLE population. The Worst Pain NRS and Worst Joint Pain NRS have been validated in other chronic conditions [23].

Prior to fielding the survey in the patient population, internal usability testing was conducted to ensure comprehension and understandability of the survey. It also served to assess the functionality of the survey to confirm that formatting and skip logic performed as expected.

Following the completion of an online eligibility questionnaire, participants completed the survey online, lasting approximately 45 min. All sections of the online survey were programmed to prevent participants from moving on to the next question before completing the previous item. However, multi-item questions where some items may not be applicable to all survey respondents did allow for missing data that were recorded for those survey items not applicable.

Pilot Survey

The survey was pilot tested through interviews of five participants with SLE residing in the US. Participants were asked to complete the SLE-UPDATE survey using their own electronic device prior to the interview. This was followed by a 60-min one-on-one telephone interview using a semi-structured discussion guide to assess comprehension and understanding. Participants were asked to provide feedback on possible issues with understanding or administration of the survey. Participants were able to access their responses to the survey during the interview to facilitate discussion. Participant feedback was reviewed, and the survey was updated to improve content and layout with the goal of improving understanding and completion.

Main Survey

Potentially eligible participants were invited to participate in the study by e-mail, using standardized templates, shared with the participants via their patient panel. Interested participants clicked on the survey link provided within the invite. Before starting the SLE-UPDATE survey, participants were screened for eligibility; if they passed, they provided electronic consent as part of the survey. The main survey was completed anonymously.

Statistical Analysis

Associations between categorical data were analyzed by chi-square test or Fisher test (for n < 5). Normality was assessed by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Means were compared by t-tests (two groups) or analysis of variance (three or more groups) for normally distributed data and by Kruskal-Wallis test for non-normally distributed data. The significance level for all statistical tests was set at p < 0.05. No adjustments were applied for multiplicity. All statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 or higher.

No data imputation was performed, and unanswered questions (where questions were not applicable) were coded as missing. Data from participants who completed only a portion of the survey were included in the analyses where possible. Participants were not able to progress through the survey without answering all questions on the screen; however, due to the skip logic patterns of some SLE-UPDATE survey items, some questions were only answered by a proportion of the overall participant sample. Some data reported as “missing” are due to a precursor question answered by the participant in the preceding section, for example, a participant selecting a type of medication would only be shown questions about that particular medication and not any other.

Results

Participants

Demographics

The main survey was completed by 500 participants, of whom 75% were female, 76% were White/Caucasian, 14% were Black or African American, and 16% were Hispanic or Latino (Table 1). The mean age (standard deviation) was 42.6 (12.7). Participants were highly educated, with 63% (n = 317) having an associate degree or higher. All patients reported they had been diagnosed with SLE by a physician.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants in the main survey

| Characteristic | Total N = 500 |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 42.6 (12.7) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 126 (25.2%) |

| Female | 373 (74.6%) |

| Intersex | 1 (0.2%) |

| Employment status, n (%) | |

| Employed (full and part time) | 291 (58.2%) |

| Student (full and part time) | 12 (2.4%) |

| Full-time homemaker | 38 (7.6%) |

| Retired | 50 (10%) |

| On disability | 107 (21.4%) |

| Unemployed | 36 (7.2%) |

| Other | 11 (2.2%) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 378 (75.6%) |

| Black or African-American | 71 (14.2%) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 4 (0.8%) |

| Asian | 26 (0.8%) |

| Mixed race or other | 29 (58%) |

| Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, n (%) | |

| No | 418 (83.6%) |

| Yes | 84 (16.8%) |

| Highest level of education completed, n (%) | |

| Less than high school | 7 (1.4%) |

| High school graduate | 59 (11.8%) |

| Some college, but no degree | 85 (17.0%) |

| Trade/technical/vocational training | 32 (6.4%) |

| Associate degree or professional certificate | 71 (14.2%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 171 (34.2%) |

| Master’s degree | 62 (12.4%) |

| Doctoral degree or higher | 13 (2.6%) |

Clinical Characteristics

The mean time since symptom onset was 12.9 years, and the mean time since diagnosis was 11.1 years. Thus, on average, approximately 2 years elapsed between onset to diagnosis. Nearly two-thirds of participants (n = 329, 66%) reported being diagnosed with SLE without nephritis and one-third (n = 171, 34%) SLE with nephritis. Fibromyalgia was reported by 31% (n = 155) of the participants and Sjogren’s by 20% (n = 100). The most common organ systems involved were musculoskeletal (muscles, and joints), reported by more than half of the study participants (n = 261, 52%), and mucocutaneous (including skin ulcers and rashes), reported by 42%. Other comorbid conditions included stomach, intestine, or liver problems (ulcers, irritable bowel syndrome, hepatitis) reported by almost a third of patients (n = 154, 31%); blood vessel disorders (clotting, atherosclerosis, Raynaud’s disease) were reported by 24%, and eye problems (e.g., cataracts) reported by 21% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comorbid conditions by treatment group

| Total N = 500 n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Eye problems more than needing glasses (cataracts) | 103 (20.6%) |

| Brain or spinal cord problems (stroke, seizures) | 51 (10.2%) |

| Lung problems (lung fibrosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma) | 98 (19.6%) |

| Heart problems (heart attack, angina, or heart valve disease) | 58 (11.6%) |

| Blood vessel problems (blood clots, atherosclerosis, or blocked arteries, Raynaud’s disease) | 121 (24.2%) |

| Stomach, intestine, or liver problems (ulcers, irritable bowel syndrome, hepatitis) | 154 (30.8%) |

| Muscle, bone, and joint problems (osteoporosis, joint pain, joint damage) | 261 (52.2%) |

| Skin problems (skin ulcers, rashes) | 212 (42.4%) |

| Diabetes | 39 (7.8%) |

| Cancer | 11 (2.2%) |

| Mental health problems (depression, anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, schizophrenia) | 169 (33.8%) |

| None of the above | 97 (19.4%) |

| “Kidney problems” selected and currently undergoing Dialysis | 24 (18.6%) |

Almost three-quarters of the sample had experienced lupus flares over the past 3 months, with the majority (n = 217; 43%) experiencing one to three lupus flares during this time frame. Most participants indicated that, on average, the severity of their flares are moderate (n = 127; 58.2%), with 12.2% (n = 61) saying most of their flares on average are severe. Around a quarter (n = 127; 26%) of participants had experienced continuously active lupus over the past 3 months (Table 3).

Table 3.

Lupus flare experience by treatment group

| Total N = 500 | |

|---|---|

| 1. The following most closely describes the frequency of lupus flares (of any severity) over the last 3 months, n (%) | |

| I did not experience any lupus flares or have active lupus symptoms (my lupus was quiet) over the past 3 months | 74 (14.8%) |

| I experienced continuously active lupus but no flares (new or worsened lupus symptoms) over the past 3 months | 127 (25.4%) |

| I experienced one to three lupus flares over the last 3 months | 217 (43.4%) |

| I experienced four to six lupus flares over the last 3 months | 54 (10.8%) |

| I experienced seven or more lupus flares over the last 3 months | 28 (5.6%) |

| 2. Considering the definitions of a mild, moderate, and severe flare above, the following most closely describes the severity of lupus flares on average, n (%) | |

| Most of my flares are mild | 148 (29.6%) |

| Most of my flares are moderate | 291 (58.2%) |

| Most of my flares are severe | 61 (12.2%) |

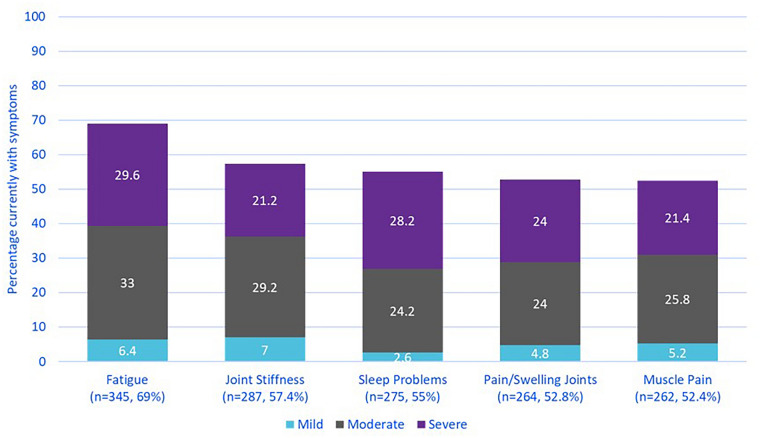

Symptom Experience

Survey participants reported a broad range of symptoms. The most frequently reported symptoms currently experienced were fatigue (69%), joint stiffness (57%), sleep problems (55%), pain or swelling in joints (53%), and muscle pain (52%), most of which was reported to be moderate to severe (Fig. 1). The mean (standard deviation) FACIT-Fatigue total score was 22.9 (12.0), indicating a substantial impact of fatigue. Sixty percent of participants reported pain all or most of the time over the past 7 days, and the Worst Pain and Worst Joint Pain NRS scores were both 5.8 (out of 10).

Fig. 1.

Current symptoms

Medication Use

The most frequently reported prescription medications were anti-malarials (n = 211, 42%), followed by oral or injected corticosteroids (n = 163, 33%), immunosuppressants (n = 163, 33%), anti-inflammatory agents (including nonsteroidal) (n = 158, 32%), aspirin (n = 118, 24%), and analgesics (n = 75, 15%). Just over half of the participants (n = 255, 51%) reported taking vitamins, minerals, or supplements as a preferred over-the-counter medication, followed by paracetamol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and herbal medications. Most participants (n = 391, 78%) reported supplementing treatments with lifestyle changes, especially through diet or exercise. Participants also reported using cannabis-derived products (n = 108, 22%) and medical marijuana (n = 91, 18%) to supplement medical treatment. Tofacitinib was another medication reported by participants but not systematically recorded because of the survey skip logic options (Table 4).

Table 4.

LupusPRO scores by treatment group

| LupusPRO | Treatment group | p-value** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-biologic N = 407 Mean (SD) | Biologic N = 93 Mean (SD) | ||

| Lupus HRQOL total | 57.1(22.7) | 48.2(21.6) | 0.0007* |

| Lupus symptoms domain | 62.9(25.7) | 53.3(27.9) | 0.0016* |

| Lupus medications domain | 52.1(29.9) | 45.3(26.1) | 0.0425* |

| Cognition domain | 62.3(32.6) | 57.1(28.7) | 0.1548 |

| Procreation domain | 66.9(39.6) | 56.7(40.3) | 0.0264* |

| Physical health domain | 60.4(28.1) | 48.7(27.5) | 0.0003* |

| Emotional health domain | 46.8(27.8) | 36.5(22.9) | 0.0009* |

| Pain & vitality domain | 48.4(27.9) | 43.8(27.1) | 0.1511 |

| Body image domain | 56.9(29.9) | 44.6(26.7) | 0.0003* |

| Lupus N-HRQOL total | 55.5(17.8) | 58.4(15.2) | 0.1554 |

| Desires & goals domain | 50.7(28.8) | 39.1(26.8) | 0.0004* |

| Coping domain | 53.9(30.2) | 62.5(30.7) | 0.0138* |

| Social support domain | 57.6(25.7) | 62.8(22.0) | 0.0726 |

| Satisfaction with medical care domain | 59.8(31.8) | 69.0(24.0) | 0.0089* |

*Significant result

**p-value from ANOVA F-test to compare mean scores between the groups

Pathway to Biologics

When asked about their experience with biologic therapies, approximately 40% of participants (n = 213, 43%) reported that their doctor had discussed the use of biologics with them. From these discussions > 70% of clinicians did recommend a biologic medication, with 75% (n = 113) of participants following their doctor’s advice to try biologic medication. Of those who did not follow the advice, the most common reasons were fear of possible side effects (n = 9, 29%), fear of infections (n = 9, 29%), or the cost of the treatment (n = 9, 29%).

Nineteen percent (n = 93) reported currently using an intravenous or injectable biologic treatment. The most frequent was belimumab (n = 57). Off-label biologic use included rituximab (n = 16), ustekinumab (n = 5), tocilizumab (n = 3), abatacept (n = 2), and “other” biologics (n = 10).

Patient Reported Health-Related Quality of Life

Health-related quality of life was assessed using the LupusPRO™. The mean total score for the HRQoL domain was 55 (SD = 23), and the non-HRQoL domain was 56 (SD = 17). Participants reported the most impacted LupusPRO™ domains were Emotional Health, Pain/Vitality, and Lupus Medications. Participants currently treated with biologics generally had lower (worse) LupusPRO™ HRQoL domain scores compared to those currently treated with non-biologics. Two LupusPRO™ non-HRQoL domains trended higher (better) in those treated with biologics, those were the Coping domain and Satisfaction with Medical Care domain (Appendix Table 2).

Treatment Satisfaction and Patient-reported Burden

Most participants were “completely” or “somewhat satisfied” in all treatment categories, although rates were lower for corticosteroids (65%), immunosuppressants (71%), and anti-malarials (55%) than for belimumab (86%) and rituximab (94%) (Fig. 2a). Nearly half of participants considered corticosteroids (48%) and immunosuppressants (49%) to be “burdensome” or “very burdensome”, while nearly two-thirds considered belimumab (67%) and rituximab (63%) “burdensome” or “very burdensome” (Fig. 2b). Only 30% of participants considered anti-malarials to be “burdensome” or “very burdensome.”

Fig. 2.

Satisfaction and burden in each treatment class

Reasons for patient perceived burden did vary by medication, but overall, administration-related reasons and side effects were most frequent. The top two patient-reported reasons for burden across the treatment categories were the following: anti-malarials—have to take pills daily (49.8%) and routine monitoring for possible eye problems (44.5%); corticosteroids—risk of long-term problems (50.6%) and experienced side effects (45.5%); immunosuppressants—experienced side effects (46%) and risk of organ damage (36.8%); belimumab—inconvenience of infusion visits (42.1%) and did not start working fast enough (28.1%); rituximab—inconvenience of infusion visits (68.8%) and routine laboratory monitoring (37.5%).

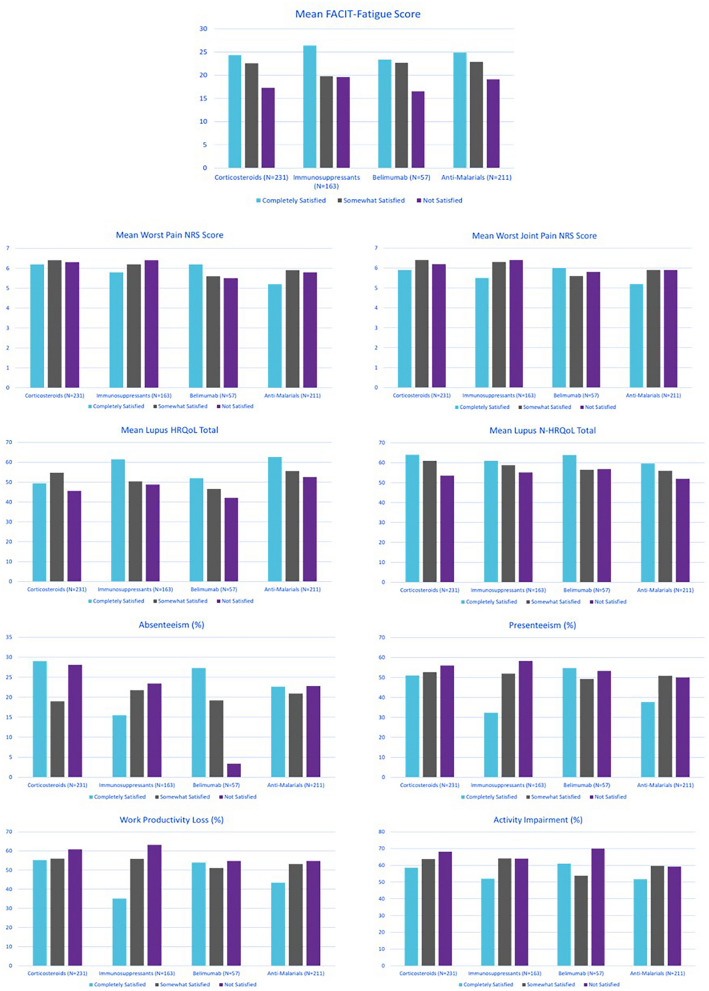

Relationship Between Treatment Satisfaction and PRO Measures

Satisfaction with treatment was generally associated with better quality of life scores (LupusPRO™ HRQoL, p = 0.016 for corticosteroids, p = 0.014 for immunosuppressants, and p = 0.0231 for anti-malarials; LupusPRO™ non-HRQoL, p = 0.001 for corticosteroids, p = 0.006 for immunosuppressants, and 0.038 for anti-malarials) (Fig. 3). Satisfaction with belimumab was not associated with improvement in the HRQoL or non-HRQoL domains of the LupusPRO™. Satisfaction with corticosteroids (p = 0.001), immunosuppressants (p = 0.014), and anti-malarials (p = 0.034) was also significantly associated with less fatigue, as indicated by a higher FACIT-Fatigue score, and satisfaction with anti-malarials was associated with reduced work productivity loss (p = 0.023) and activity impairment (p = 0.041). For rituximab, numbers of participants were too low to analyze associations. For all treatments, Worst Pain, Worst Joint Pain, and WPAI assessments of productivity and activity impairment did not statistically significantly improve as treatment satisfaction improved and still showed substantial impairment even for participants who indicated that they were completely satisfied with the individual treatments.

Fig. 3.

Association between satisfaction and PRO measure

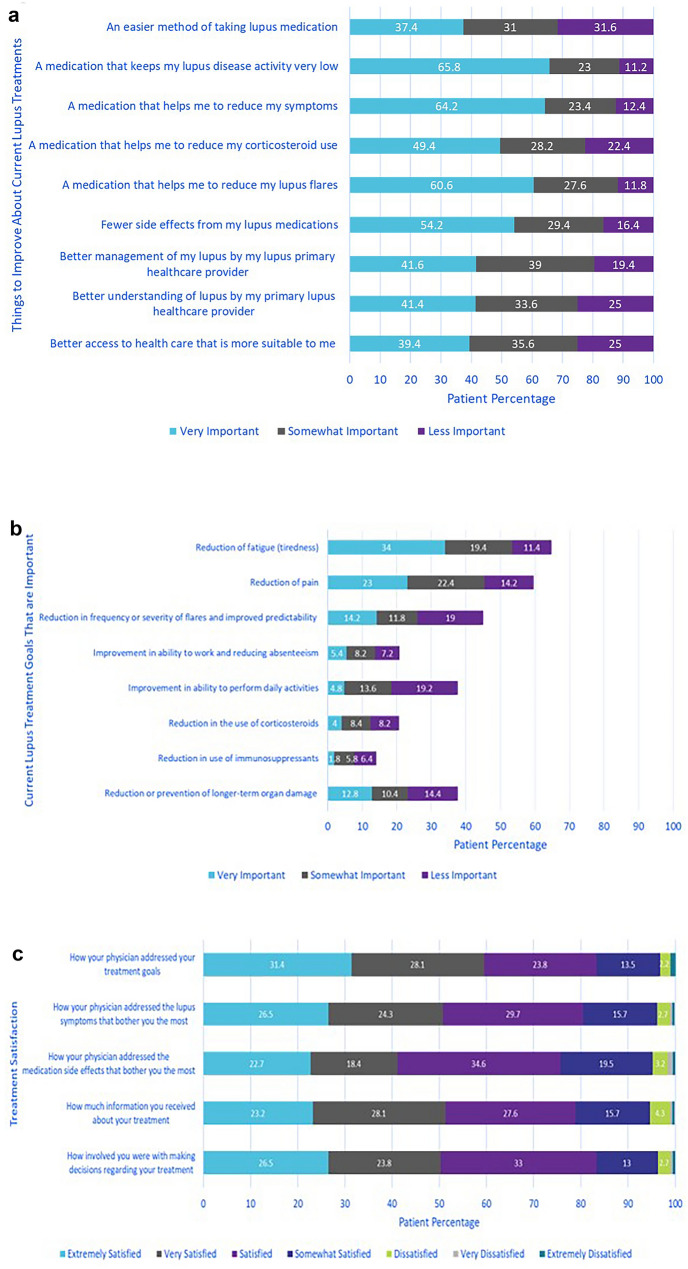

Desired Improvements with SLE Therapy and Treatment Goals

In response to a question on what improvements they would like to see with their current lupus treatment, the three most frequent choices, selected by > 60% of participants, were that they would like their medication to: keep lupus disease activity very low, reduce lupus symptoms, and reduce lupus flares (Fig. 4a). Fewer participants indicated reducing corticosteroids, having fewer side effects, and an easier method of taking lupus medication as their most important desired improvements to their current lupus medications.

Fig. 4.

Treatment satisfaction goals

Participants were given eight options of potential treatment goals covering individual symptom improvement, flares, organ damage, reduced medication use, and work productivity (Fig. 4a). They were asked to select their top three treatment goals. Of the treatment goal options presented to participants, reducing fatigue, reducing pain, and reducing the frequency or severity of flares were the most common goals reported as “very important.” Goals that were of lesser importance included reducing or preventing long-term organ damage, reducing steroid use, and reducing immunosuppressant use (Fig. 4a).

Across all survey participants (n = 500), 30% indicated that their physician’s goals for their current therapy matched their own goals “very closely,” 47% said their physician’s goals and their own matched “somewhat closely,” while 16% indicated their physician’s goals and their own matched “not very closely” or “not at all.” Approximately 2/3 of survey participants (n = 315; 63%) indicated their healthcare provider had not asked them about their most important treatment goals over the past 3 months. Of the remaining 37% (n = 185) of survey participants who had discussed treatment goals with their physician over the past 3 months, most participants, approximately 80%, had a high degree of satisfaction with how their physician addressed their treatment goals and with their participation in decision making with their clinician (Fig. 4b).

Discussion

This survey of 500 adults with SLE in the US explored the patients’ burden of disease and their experiences, satisfaction, and goals within the current therapeutic landscape. Survey participants described a wide range of SLE-related symptoms; the most commonly reported were fatigue, musculoskeletal symptoms, and sleep disturbance. Patient-reported pain was also prominent. As described in other studies, these symptoms had significant impact on patients’ HRQoL [24–27].

As previously reported in patient surveys [28], prescribed therapies included anti-malarials, corticosteroids, and immunosuppressants, with relatively little use of biologics. Unexpectedly in our study, anti-malarial use was less frequent than reported in other surveys. The current study also showed that participants were more satisfied with biologics (belimumab and rituximab) and relatively less satisfied with corticosteroids and immunosuppressants, even though biologics were considered more burdensome and were generally associated with a lower HRQoL compared to non-biologic therapies. Our results are similar to those from another observational study where patients with SLE reported being highly satisfied with their treatment despite describing a substantial impact of side effects [29].

When asked why they considered their medication(s) to be burdensome, participants in our survey most commonly indicated reasons related to experiencing side effects, or inconvenient administration of their therapies, although a slow onset of effect, need to have procedures for routine monitoring for adverse effects, and risk of longer-term complications associated with the treatment were also frequently reported. These results highlight the multi-factorial etiology of treatment satisfaction which could also be impacted by individual expectations in relation to past medication experiences.

For all medications, participants who reported high levels of satisfaction were still experiencing high levels of fatigue and pain. Fatigue appeared to play a role in satisfaction, mainly as it generally decreased as patient-reported satisfaction improved. However, improvement in pain was not associated with improvement in satisfaction in this analysis, although fatigue and pain have both been demonstrated to be drivers of treatment satisfaction in other surveys [4–5]. The apparent paradox between the reported high satisfaction despite inadequate relief from two of the SLE symptoms reported as the most impactful (i.e., fatigue and pain) could be the result of the lived experience with fatigue and pain as chronic symptoms and their expected inevitability. These symptoms did play a prominent role in the desired future state of medication therapy and as priority treatment goals.

The most frequently selected desired improvement for current SLE treatments was a medication that would maintain low lupus disease activity. This coincides, at least conceptually, with the current initiatives around treat-to-target endpoints, such as clinician-assessed remission or low disease activity, which are usually composite outcome measures based on one or more validated disease activity indices often in conjunction with minimization of steroid use [30–31]. However, physicians and patients with SLE take into account different aspects of the disease when assessing disease activity [32]. Thus, the conceptual definition of low disease activity might have a different meaning to clinicians and their patients. Including one or more PRO measures as part of a composite assessment of a SLE low disease activity state may help in bridging the gap between patient and clinician assessments as has been done for other disease states, such as psoriatic arthritis [33–34].

As treatment goals, participants prioritized reduction of symptoms, especially fatigue, pain, and flares. Overall, reduction in organ damage and use of corticosteroids was considered to be of lower priority. Although treatment guidelines emphasize reduction of corticosteroid use [3], survey participants did not consider this a high priority. This could indicate a need for patient education about risks associated with long-term steroid use and the importance of trying to reduce steroid doses. This also highlights the need for new steroid-sparing treatments, which may in turn help elevate steroid reduction priority from the patient perspective and improve patient outcomes [35].

Assessment of the collaboration between the healthcare provider and their patient on the setting of treatment goals found closely matched goals reported by 30% of survey participants, with 16% indicating their treatment goals did not match their physicians. In the survey participants who said their physician had asked them about their treatment goals recently were generally satisfied with their treating physician and their own involvement in decision making. Additionally, the use of PROs in clinical care can assist with physician/patient dialogue, which may add to general satisfaction and shared decision-making; steroid use and long-term risks are another area that can warrant shared discussion. This concept was also demonstrated in a cohort of SLE patients by Bennett and colleagues who found that harmonization of the goals of treatment between the physician and patient predicted better patient adherence, as well as higher satisfaction, and quality of life [36].

This survey benefited from a large, diverse sample of SLE patients that was representative of the US population in terms of race and employment, albeit with a somewhat higher average education level, which may not be a true representation of the US SLE population [37]. The results, however, may not be generalizable to other countries because of different populations and medical practices. Patients’ self-reported diagnosis of SLE was not verified. Another potential limitation is that, as with other online surveys, the SLE-UPDATE survey was unable to capture the perspectives of participants who do not have access to electronic devices. Furthermore, the online survey may have favored those with less severe disease activity and the ability to participate. The wording of the questions and responses may have also affected the study outcome. In some cases, low numbers may have limited the ability to make inferences.

Conclusions

This survey showed that patients with SLE in the US reported relatively high rates of satisfaction with current therapies despite identifying heavy treatment burdens, especially residual pain and fatigue. The study also showed that reduced fatigue, pain, and flares were indicated as the most important treatment goals for these patients. The study results further demonstrated the importance of continuous physician/patient discussions around treatment goals and decision making. Given the growing interest in assessment of individual organ domains within SLE, future research to understand the symptom and treatment burden, HRQoL, treatment satisfaction, and treatment goals in patients predominantly affected with a specific manifestation (e.g., arthritis, or skin rash) could help elucidate current unmet need related to individual symptoms.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the patients who participated in this research.

Funding

Funding for this study and the journal’s Rapid Service Fee was provided by Eli Lilly and Company.

Medical Writing

Medical writing was provided by Phillip S. Leventhal, PhD, from Evidera.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Julie A. Birt, Monica A. Hadi, Nashmel Sargalo, Ella Brookes, and Paul Swinburn conceived the study, participated in its co-ordination, and guided the statistical analysis. Julie A. Birt, Monica A. Hadi, Nashmel Sargalo, Ella Brookes, Paul Swinburn, Leslie Hanrahan, Karin Tse, Natalia Bello, Kirstin Griffing, Maria E. Silk, Laure A. Delbecque, and Diane Kamen participated in the development of the study surveys, and interpretation of the study data, as well as contributed towards the manuscript. Anca D. Askanase was involved in interpretation of the data, critical revision for important intellectual content, and contributed towards the manuscript.

Disclosures

Julie A. Birt, Natalia Bello, Kirstin Griffing, Maria E. Silk, Laure A. Delbecque are current employees and shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company. Monica A. Hadi, Nashmel Sargalo, Ella Brookes and Paul Swinburn are employees of Evidera, which was paid by Eli Lilly for work related to this manuscript. Karin Tse, employee of Lupus Foundation of America, employee of Lupus Foundation of America at the time of the study was conducted were paid consultants to Eli Lilly. Diane Kamen is employee of Medical University of South Carolina Health was a paid consultant to Eli Lilly. Anca D. Askanase is an employee of Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons was a paid consultant to Eli Lilly.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was approved by a US ethical institutional review board in accordance with local law. Advarra, a US-based institutional review board, reviewed study documents (protocol, informed consent form, and patient survey) prior to completion of any patient data. Documentation was updated following interviews with patients in the pilot phase, and an amendment was sought prior to collecting data in the main study. All participants completed an electronic informed consent form prior to completing the online survey. All data were de-identified and kept confidential in accordance with International Council for Harmonization for Good Clinical Practice.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.FDA. BENLYSTA® (belimumab) Label. 2012.

- 2.Kariburyo F, Xie L, Sah J, Li N, Lofland JH. Real-world medication use and economic outcomes in incident systemic lupus erythematosus patients in the United States. J Med Econ. 2020;23(1):1–9. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2019.1678170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fanouriakis A, Kostopoulou M, Alunno A, Aringer M, Bajema I, Boletis JN, Cervera R, Doria A, Gordon C, Govoni M, Houssiau F, Jayne D, Kouloumas M, Kuhn A, Larsen JL, Lerstrom K, Moroni G, Mosca M, Schneider M, Smolen JS, Svenungsson E, Tesar V, Tincani A, Troldborg A, van Vollenhoven R, Wenzel J, Bertsias G, Boumpas DT. 2019 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(6):736–745. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mozaffarian N, Lobosco S, Lu P, Roughley A, Alperovich G. Satisfaction with control of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis: physician and patient perspectives. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:2051–2061. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S111725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pascoe K, Lobosco S, Bell D, Hoskin B, Chang DJ, Pobiner B, Ramachandran S. Patient- and physician-reported satisfaction with systemic lupus erythematosus treatment in US clinical practice. Clin Ther. 2017;39(9):1811–1826. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franklyn K, Lau CS, Navarra SV, Louthrenoo W, Lateef A, Hamijoyo L, Wahono CS, Le Chen S, Jin O, Morton S. Definition and initial validation of a lupus low disease activity state (LLDAS) Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(9):1615–1621. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gladman DD, Ibanez D, Urowitz MB. Systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index 2000. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(2):288–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chessa E, Piga M, Floris A, Devilliers H, Cauli A, Arnaud L. Use of Physician Global Assessment in systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review of its psychometric properties. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020 doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saccon F, Zen M, Gatto M, Margiotta DPE, Afeltra A, Ceccarelli F, Conti F, Bortoluzzi A, Govoni M, Frontini G, Moroni G, Dall'Ara F, Tincani A, Signorini V, Mosca M, Frigo AC, Iaccarino L, Doria A. Remission in systemic lupus erythematosus: testing different definitions in a large multicentre cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(7):943–950. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parodis I, Johansson P, Gomez A, Soukka S, Emamikia S, Chatzidionysiou K. Predictors of low disease activity and clinical remission following belimumab treatment in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2019;58(12):2170–2176. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neville C, Clarke AE, Joseph L, Belisle P, Ferland D, Fortin PR. Learning from discordance in patient and physician global assessments of systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(3):675–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yen JC, Abrahamowicz M, Dobkin PL, Clarke AE, Battista RN, Fortin PR. Determinants of discordance between patients and physicians in their assessment of lupus disease activity. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(9):1967–1976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al Sawah S, Daly RP, Foster SA, Naegeli AN, Benjamin K, Doll H, Bond G, Moshkovich O, Alarcon GS. The caregiver burden in lupus: findings from UNVEIL, a national online lupus survey in the United States. Lupus. 2017;26(1):54–61. doi: 10.1177/0961203316651743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lupus Foundation of America. "UNVEIL" Survey Reveals a Life Interrupted by Lupus. Accessed 18 August, 2020. https://www.lupus.org/news/unveil-survey-reveals-a-life-interrupted-by-lupus

- 15.Jolly M, Pickard AS, Block JA, Kumar RB, Mikolaitis RA, Wilke CT, Rodby RA, Fogg L, Sequeira W, Utset TO, Cash TF, Moldovan I, Katsaros E, Nicassio P, Ishimori ML, Kosinsky M, Merrill JT, Weisman MH, Wallace DJ. Disease-specific patient reported outcome tools for systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;42(1):56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azizoddin DR, Weinberg S, Gandhi N, Arora S, Block JA, Sequeira W, Jolly M. Validation of the LupusPRO version 18: an update to a disease-specific patient-reported outcome tool for systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2018;27(5):728–737. doi: 10.1177/0961203317739128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cella D. The functional assessment of cancer therapy-anemia (FACT-An) Scale: A new tool for the assessment of outcomes in cancer anemia and fatigue. Semin Hematol. 1997;34(3 Suppl 2):13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4(5):353–365. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.British Pain Society. Outcome Measures. Accessed 19 February, 2020. https://www.britishpainsociety.org/static/uploads/resources/files/Outcome_Measures_January_2019.pdf

- 20.Alghadir AH, Anwer S, Iqbal A, Iqbal ZA. Test–retest reliability, validity, and minimum detectable change of visual analog, numerical rating, and verbal rating scales for measurement of osteoarthritic knee pain. J Pain Res. 2018;11:851. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S158847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evidera. Meeting Minutes Project: EVM-27209. 2020;

- 22.Strand V, Simon LS, Meara AS, Touma Z. Measurement properties of selected patient-reported outcome measures for use in randomised controlled trials in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review. Lupus Sci. Med. 2020;7(1):e000373. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2019-000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T, French M. Measures of adult pain: Visual analog scale for pain (vas pain), numeric rating scale for pain (nrs pain), mcgill pain questionnaire (mpq), short-form mcgill pain questionnaire (sf-mpq), chronic pain grade scale (cpgs), short form-36 bodily pain scale (sf-36 bps), and measure of intermittent and constant osteoarthritis pain (icoap) Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(S11):S240–S252. doi: 10.1002/acr.20543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon C, Isenberg D, Lerstrom K, Norton Y, Nikai E, Pushparajah DS, Schneider M. The substantial burden of systemic lupus erythematosus on the productivity and careers of patients: a European patient-driven online survey. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52(12):2292–2301. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kent T, Davidson A, Newman D, Buck G, D'Cruz D. Burden of illness in systemic lupus erythematosus: results from a UK patient and carer online survey. Lupus. 2017;26(10):1095–1100. doi: 10.1177/0961203317698594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piga M, Congia M, Gabba A, Figus F, Floris A, Mathieu A, Cauli A. Musculoskeletal manifestations as determinants of quality of life impairment in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2018;27(2):190–198. doi: 10.1177/0961203317716319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamayo T, Fischer-Betz R, Beer S, Winkler-Rohlfing B, Schneider M. Factors influencing the health related quality of life in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: long-term results (2001–2005) of patients in the German Lupus Erythematosus Self-Help Organization (LULA Study) Lupus. 2010;19(14):1606–1613. doi: 10.1177/0961203310377090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morgan C, Bland AR, Maker C, Dunnage J, Bruce IN. Individuals living with lupus: findings from the LUPUS UK Members Survey 2014. Lupus. 2018;27(4):681–687. doi: 10.1177/0961203317749746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mathias SD, Berry P, Pascoe K, de Vries J, Askanase AD, Colwell HH, Chang DJ. Treatment satisfaction in systemic lupus erythematosus: Development of a patient-reported outcome measure. J Clin Rheumatol. 2017;23(2):94–101. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tselios K, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB. How can we define low disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus? Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;48(6):1035–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Vollenhoven R, Voskuyl A, Bertsias G, Aranow C, Aringer M, Arnaud L, Askanase A, Balazova P, Bonfa E, Bootsma H, Boumpas D, Bruce I, Cervera R, Clarke A, Coney C, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Czirjak L, Derksen R, Doria A, Dorner T, Fischer-Betz R, Fritsch-Stork R, Gordon C, Graninger W, Gyori N, Houssiau F, Isenberg D, Jacobsen S, Jayne D, Kuhn A, Le Guern V, Lerstrom K, Levy R, Machado-Ribeiro F, Mariette X, Missaykeh J, Morand E, Mosca M, Inanc M, Navarra S, Neumann I, Olesinska M, Petri M, Rahman A, Rekvig OP, Rovensky J, Shoenfeld Y, Smolen J, Tincani A, Urowitz M, van Leeuw B, Vasconcelos C, Voss A, Werth VP, Zakharova H, Zoma A, Schneider M, Ward M. A framework for remission in SLE: consensus findings from a large international task force on definitions of remission in SLE (DORIS) Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(3):554–561. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Golder V, Ooi JJY, Antony AS, Ko T, Morton S, Kandane-Rathnayake R, Morand EF, Hoi AY. Discordance of patient and physician health status concerns in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2018;27(3):501–506. doi: 10.1177/0961203317722412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coates LC, Fransen J, Helliwell PS. Defining minimal disease activity in psoriatic arthritis: a proposed objective target for treatment. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(1):48–53. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.102053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wervers K, Luime JJ, Tchetverikov I, Gerards AH, Kok MR, Appels CWY, van der Graaff WL, van Groenendael J, Korswagen LA, Veris-van Dieren JJ, Hazes JMW, Vis M. Comparison of disease activity measures in early psoriatic arthritis in usual care. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2019;58(12):2251–2259. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamirou F, Arnaud L, Talarico R, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus: state of the art on clinical practice guidelines. RMD Open. 2019;4:e000793. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bennett JK, Fuertes JN, Keitel M, Phillips R. The role of patient attachment and working alliance on patient adherence, satisfaction, and health-related quality of life in lupus treatment. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(1):53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.United States Census Bureau. Quick Facts United States. Accessed 19 Jun 2020, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.