Abstract

Introduction

We conducted a systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) regarding quality of life, disability, mood abnormalities (anxiety, depression), fatigue, illness perceptions and fibromyalgia in Takayasu arteritis (TAK). Wherever available, comparisons with healthy controls, disease controls or longitudinal changes in PROMs were noted.

Methods

MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, Web of Science and Pubmed Central databases, major recent international rheumatology conference abstracts, clinical trial databases and the Cochrane library were searched for relevant articles. Wherever possible, outcome measures across studies were pooled using the restricted maximum likelihood model. Inter-group differences were pooled and compared using standardized mean differences (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic. Quality of randomized controlled trials was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. For cross-sectional and cohort studies, the Joana Briggs Institute checklist and Newcastle–Ottawa scale were used, respectively. GRADE methodology was used to determine the certainty of evidence for outcomes.

Results

Twenty-one studies (all but one observational) involving 1311 patients with TAK and 308 healthy controls were identified. Ten studies (559 TAK patients, 182 healthy controls were synthesized in a meta-analysis. Patients with TAK had worse quality of life (pooled SMD − 6.66, 95% CI − 10.08 to − 3.23 for individual domains; − 0.64, 95% CI − 1.19 to − 0.09 for pooled physical and mental component scores of 36-item Short Form Survey), depression (SMD 0.26, 95% 0.05–0.47) and anxiety (SMD 0.34, 95% CI − 0.06 to 0.75) scores and higher disability (SMD 0.64, 95% CI 0.43–0.84) than healthy controls. Patients with active TAK had worse quality of life, depression and work impairment when compared with those with inactive disease. Included studies were of moderate to high quality. Certainty of evidence for individual outcomes was low to very low.

Conclusion

Literature on PROMs in TAK, albeit sparse, appears to indicate worse scores in patients with TAK compared to healthy individuals. These results, however, require cautious interpretation. Development of a TAK-specific PROM is an important focus of the research agenda.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40744-021-00355-3.

Keywords: Takayasu arteritis, Patient-reported outcome measures, Quality of life, Depression, Anxiety, Fibromyalgia

Key Summary Points

| Published literature on patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in patients with Takayasu arteritis (TAK) is sparse. |

| Available evidence appears to suggest that patients with TAK have greater disability and depression than healthy individuals and that active TAK is associated with worse quality of life, disability, depression and anxiety. |

| However, the comparison of PROMs from patients with TAK and healthy controls and from those with active and those with inactive disease is based on small numbers of studies with considerable statistical heterogeneity in some of the pooled estimates (therefore, requiring cautious interpretation). |

| Research gaps in this area include the assessment of longitudinal changes in PROMs in patients with TAK, changes following therapy and relationship of PROMs with disease activity. |

| There is a need to develop a validated disease-specific PROM for patients with TAK. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a slide deck, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.15067938.

Introduction

The importance of comorbidities in rheumatic diseases, including vasculitis, is increasingly being recognized [1, 2]. The Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) group has proposed core outcome measures in different diseases, including large vessel vasculitis (LVV) [3]. Takayasu arteritis (TAK) is a subtype of LVV commonly affecting young females [4]. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) relate to the patient’s perceptions of living with disease [5]. PROMs are a well recognized assessment tool for the more common rheumatic diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and spondyloarthritis [6], but the development of PROMs for vasculitides is an evolving area [3, 7, 8]. Collaborative efforts have successfully developed and validated a PROM for anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) [9]. In the absence of a similarly validated tool, various generic PROMs have been used in TAK, such as the 36-item Short Form Survey (SF-36) [10], the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) [11, 12] and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [13].

The aim of this systematic review was to assess the degree of impairment of quality of life (QOL), disability, mood abnormalities, fatigue, illness perceptions and fibromyalgia in patients with TAK reported using different PROMs. Further, we systematically evaluated differences between PROMs in patients with TAK compared with healthy controls or other disease conditions, and their relationship with disease activity.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted according to guidance provided by the Cochrane collaboration [14] and reported in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) (Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] Table S1) [15], its amendment regarding literature searches (PRISMA-S) (ESM Table S2) [16] and the meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology guidelines (ESM Table S3) [17]. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Study Selection

Studies reporting PROMs in TAK (both adult-onset [18–21] and childhood-onset [22] forms) reporting original data on any PROM were included. Due to the paucity of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in TAK [23], both RCTs and observational studies (with or without control group) were included. Review articles, case reports, editorials and letters to editors were excluded.

Literature Searches

MEDLINE (via OVID), EMBASE (via OVID), Pubmed Central (via Pubmed), Web of Science and Scopus were searched on 12 April 2021 without any date or language restrictions (search strategy presented in ESM Table S4). Identified articles were downloaded to Endnote X9.3 and duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts were screened to identify relevant full-text articles, noting reasons for exclusion. Conference abstracts of major international Rheumatology conferences from 2018 to 2020 (American College of Rheumatology [ACR], European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology [EULAR], Asia–Pacific League of Nations for Rheumatology), Cochrane database of controlled clinical trials (CENTRAL) and clinicaltrials.gov were hand searched for completed but unpublished studies of TAK reporting PROMs. Searches were analyzed in duplicate by two investigators (DPM, PP); any disagreements were resolved by mutual discussion. Additional studies were included based on prior knowledge or screening reference lists of previous reviews [24]. The search results are shown in ESM Fig. S1.

Quality Analysis of Included Studies

Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 tool [25] for RCTs, the Newcastle–Ottawa scale for cohort studies [26] and the Joanna Briggs Institute checklist for cross-sectional studies [27] were used. The study quality of conference abstracts was not assessed. Publication bias was evaluated if at least ten studies assessed a particular outcome [28, 29].

Data Extraction

Data were extracted to pre-designed paper proformas independently by two investigators (DPM, UR). Means and standard deviations (SD) were imputed from medians with interquartile range or medians with range using published methods [30, 31].

Data Analysis

Data were pooled using the STATA version16.1 I/C software package (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA), using the restricted maximum likelihood model (REML) to estimate 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Differences between groups for a particular PROM were pooled after computing the standardized mean difference (SMD) using Hedges’ g. Effect sizes were rated as small, medium or large based on SMD cut-offs of 0.2, 0.5 and 0.8, respectively [32]. The random effects model was used a priori due to the expected heterogeneity owing to the small sample sizes [33] of the TAK studies and diverse PROMs assessed. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using I2 statistic; values > 50% denoted significant heterogeneity [14]. In such cases, individual studies were excluded to assess whether this exclusion ameliorated the observed heterogeneity. Results were summarized descriptively wherever appropriate. Subgroup analyses were pre-planned for adult and childhood-onset TAK [34, 35]. Studies using version 2 of SF-36 were excluded to evaluate the impact of the version of SF-36 in a secondary analysis. Sensitivity analyses were based on study design (cross-sectional or cohort).

Analysis of the Certainty of Evidence

Certainty of evidence for pooled outcomes was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) profiler [36].

Results

Summary of Included Studies

Twenty-one studies (1311 patients with TAK, 308 healthy controls) were identified [37–57], all but one [52] were observational. Ten studies (559 patients with TAK, 182 healthy controls) were synthesized in meta-analysis [37, 39–42, 45, 51, 53, 55, 56], all of whom reported patients with prevalent disease (rather than newly diagnosed disease) on a variety of treatments (ESM Table S5). Most subjects included in the studies were female. Thirteen studies included healthy or disease controls. Eight studies reported longitudinal changes in PROMs. Twelve studies were multicentric. Various PROMs were used for QOL (SF-36, original and version 2 [10], EuroQol 5 dimensions [EQ-5D] [58]], mood disorders (HADS-anxiety [HADS-A], HADS-depression [HADS-D] [13]), fatigue (Multidimensional fatigue inventory [MFI-20] [59]), disability (HAQ, International Physical Activity Questionnaire—Short Form [IPAQ-SF] [60], Walking Impairment Questionnaire (WIQ) [61], Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI) [62]], perceptions about illness (Illness Perception Questionnaire [IPQ-R] [63], Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire [BIPQ] [64], Nottingham Health Profile [NHP] [65]) and fibromyalgia [66]. Characteristics of included studies are summarized in Table 1. Figure 1 presents the geographical distribution of identified studies. Pre-planned subgroup analyses based on childhood or adult-onset TAK were not feasible since only one study exclusively focused on childhood-onset TAK [55].

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| First author of study (reference No) | Number of patients | Gender (male:female) | Age (years) | Duration of disease (years) | QOL outcomes assessed | Included comparison with control | Longitudinal changes in QOL | Relationship of QOL with disease activity | Single/ Multicenter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abularrage 2008 [37] | 158 TAK | 14:144 | 42.2 ± 1.1a | 11.7b | SF-36 | Yes (DC) | No | No | Multi |

| Akar 2008 [38] | 51 TAK, 75 HC | 10:41 TAK, 22:53 HC | 38.4 ± 13.5 aTAK, 38.8 + 10.9a HC | 7.6 ± 7.5a | SF-36, NHP | Yes (HC, DC) | No | Yes | Multi |

| Quartuccio 2012 [39] | 10 TAK | NA | NA | NAd | SF-36, EQ-5D | Yes (HC, DC) | Yes | No | Multi |

| Alibaz-Oner 2013 [40] | 55 TAK, 40 HC | 6: 49 TAK, 9: 31 HC | 42.3 ± 12.4a TAK, 41 ± 10.8a HC | 4.7 ± 6.5 | SF-36, HADS, HAQ, FM | Yes (HC) | Yes | No | Single |

| Grayson 2013 [41] | 57 TAK | 3:54 | 49.4 + 34.1a | 9.5 ± 14.8a | IPQ-R, MFI-20 | Yes (DC) | No | No | Multi |

| Yilmaz 2013 [42] | 165 TAK, 109 HC | 12: 153 TAK, 10:99 HC | 41.3 + 12.1a TAK, 40.4 ± 10.3a HC | 8.7 + 7.7a | SF-36, HADS, HAQ | Yes (HC) | No | Yes | Multi |

| Sreih 2016 [43] | 207 TAK | 6: 201 | 38.7 + 12.9a | NA | SF-36 | No | Yes | Yes | Multi |

| Gunsay 2017 [44] | 68 TAK | 8:60 | 42.9b | NA | SF-36 | No | No | No | Multi |

| Oliveira 2017 [45] | 6 TAK | 0:6 | 35.3 + 6.6a | 11.3 + 5.9a | SF-36, HAQ | No | Yes | No | Single |

| Omma 2017 [46] | 165 TAK, 51 HC | 19:146 TAK, 6:45 HC | 32.5 + 11.7a TAK, 38.2 ± 7.9a HC | 6 ± 5.4a | SF-36 | Yes (HC) | No | Yes | Multi |

| Chen 2018 [47] | 14 TAK | NA | NA | NA | EQ-5D | No | Yes | No | Single |

| Sreih 2018 [48] | 31 TAK | NA | NA | NA | Qualitative study | No | No | No | Multi |

| Campochiaro 2020 [49] | 23 TAK | 2:21 | 43.8 + 14.4a | 8.0 ± 5.1a | HAQ | No | Yes | No | Single |

| Garen 2020 [50] | 33 TAK | 0:33 TAK | 32c TAK | 8.9c | SF-36 | Yes (HC) | No | No | Single |

| Luna-Vargas 2020 [51] | 15 TAK | 0:15 | 38.7 ± 11.1a | 10 ± 8.8a | SF-36, HAQ, MFI | No | No | No | Single |

| Nakaoka 2020 [52] | 36 TAK | 5:31 TAK | 30.9 ± 15.5a TAK | 5.0 ± 6.0a | SF-36 | Yes (HC) | Yes | No | Multi |

| Rimland 2020 [53] | 56 TAK | 11:45 | 33.4 ± 15.9a | 7.4 ± 10.1a | SF-36, BIPQ, MFI | Yes (DC) | No | Yes | Single |

| Schwartz 2020 [54] | 47 TAK | 7:40 | 34 ± 14a | NA | BIPQ | Yes (DC) | Yes | No | Single |

| Astley 2021 [55] | 17 TAK, 17 HC | 6:11 TAK, 6:11 HC | 18.4 ± 3.4a TAK, 18.5 + 3.5b HC | 9.5 + 4.2a | SF-36 | Yes (HC) | No | No | Multi |

| dos Santos 2021 [56] | 20 TAK, 16 HC | 0:20 TAK, 0:16 HC | 41.9 ± 6.2a TAK | 15.2 ± 7.8a | SF-36, HAQ, IPAQ-SF, WIQ | Yes (HC) | No | No | Multi |

| Erdal 2021 [57] | 77 TAK | 7:70 | 44 ± 9.3a | 7 ± 3.7a | IPQ-R, HADS, WPAI | No | No | Yes | Single |

BIPQ Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire, DC Disease controls, EQ-5D EuroQol 5 dimensions, FM Fibromyalgia, HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, HAQ Health Assessment Questionnaire, HC healthy controls, IPAQ-SF International Physical Activity Questionnaire – Short Form, IPQ-R Illness Perception Questionnaire, MFI Multidimensional fatigue inventory, NA Not available, NHP Nottingham Health Profile, QOL quality of life, SF-36 36 item Short Form Survey, TAK Takayasu arteritis, WIQ Walking Impairment Questionnaire, WPAI Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire

aMean (standard deviation [SD])

bMean

cMedian

dMean disease duration (± SD) for entire cohort of 15 patients at baseline was 3.2 ± 2.5 years (not separately mentioned for the ten patients for whom SF-36 and EQ-5D were reported)

Fig. 1.

Geographical distribution of studies assessing patient-reported outcome measures in Takayasu arteritis. Figure generated using the map chart function of Microsoft Excel for Mac v 16.48

Quality Assessment of Included Studies

The RCT of tocilizumab in TAK [52] had some concern about the risk of bias due to unclear allocation concealment and unavailability of a pre-published statistical analysis plan. Most cross-sectional studies were of high quality. Some were downgraded due to lack of adjustment for potential confounders and concerns about the appropriate statistical analysis (ESM Table S6). Most cohort studies were of moderate quality (Newcastle–Ottawa scale scores ranged from 4 to 7) and were downgraded for the lack of appropriate control group or selection of control groups unadjusted for confounders (ESM Table S7). Assessment of publication bias was not feasible.

Patient-Reported Outcome Measures

Quality of Life Assessment

36-Item Short Form Survey

The SF-36 assesses QOL in eight domains, four physical (physical function, physical role limitation, bodily pain and general health) and four mental (social functioning, emotional role limitation, mental health and vitality). Each domain is measured with a score ranging from 0 to 100. In addition, summary scores are provided for the physical component score and the mental component score, respectively (each with their four domains). Higher scores indicate better QOL [10].

Fifteen studies evaluated SF-36 in TAK [37–40, 42–46, 50–53, 55, 56], nine studies compared TAK patients with healthy controls [38–40, 42, 46, 50, 52, 55, 56] and three studies compared TAK patients with disease controls [38, 39, 53]. Five studies each reported longitudinal changes in SF-36 in TAK [39, 40, 43, 45, 52] and the relationship with disease activity [38, 42, 43, 46, 53]. Nine studies used version 1 of SF-36 [37–40, 42, 46, 51, 55, 56] and two used version 2 of SF-36 [52, 53] (the version used could not be determined for four studies [43–45, 50]).

Individual SF-36 Domains

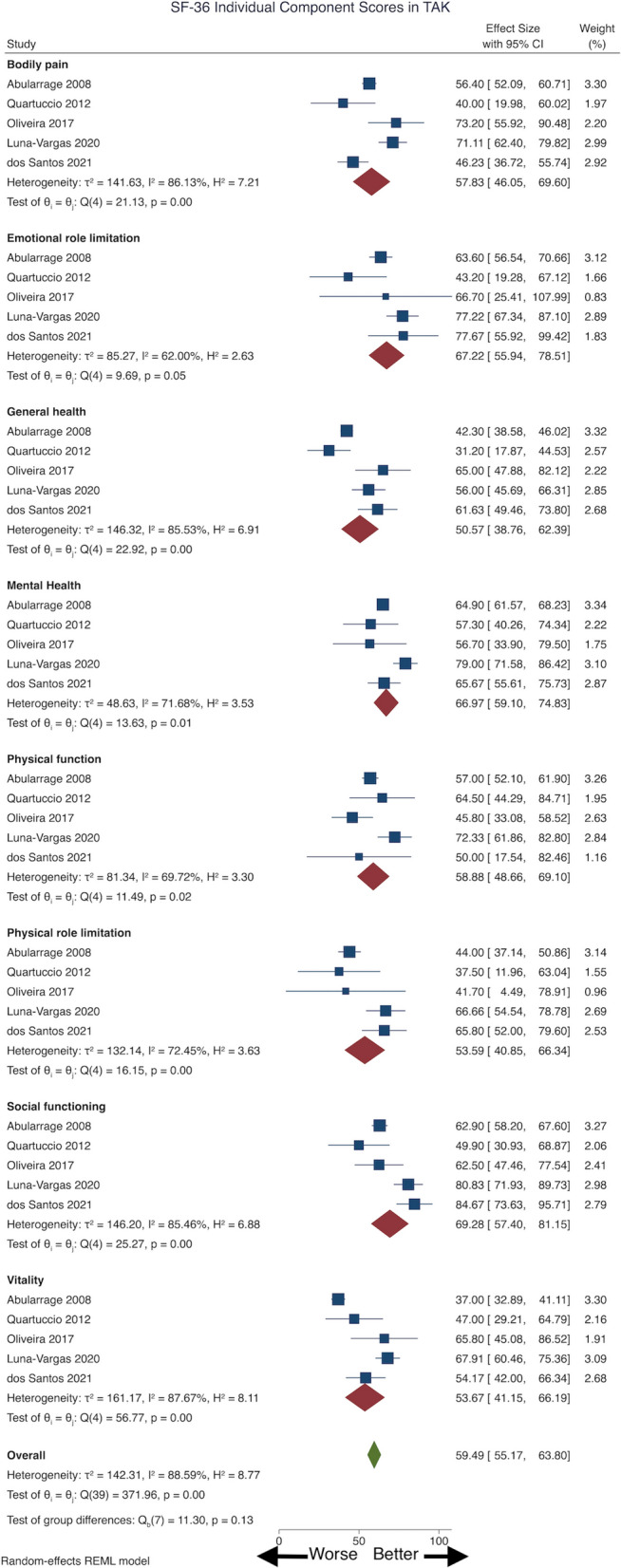

Pooling data from five studies [37, 39, 45, 51, 56] (three cross-sectional, two cohort; 209 patients with TAK), mean (95% CI) SF-36 component scores were obtained in different domains: physical function (58.88, 95% CI 48.66–69.10), physical role limitation (53.39, 95% CI 40.85–66.34), bodily pain (57.83, 95% CI 46.05–69.6), general health (50.57, 95% CI 38.76–62.39), social functioning (69.28, 95% CI 57.40–81.15), emotional role limitation (67.22, 95% CI 55.94–78.51), mental health (66.97, 95% CI 59.10–74.83) and vitality (53.67, 95% CI 41.15–66.19) (Fig. 2); all showed considerable heterogeneity. Excluding the study of Quartuccio et al. [39], the I2 for the domain of emotional role limitation but not for other domains was reduced to < 50%. Excluding the study of Luna–Vargas [51] reduced I2 to < 50% for the domains of physical function, emotional role limitation and mental health but not for other domains. Thus, no single study adequately explained the heterogeneity. Sensitivity analyses reduced I2 < 50% for emotional role limitation, mental health, physical role limitation, social functioning and vitality domains for the cohort studies but not for cross-sectional studies.

Fig. 2.

Pooled 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) individual component scores in patients with Takayasu arteritis (TAK). CI Confidence interval, REML restricted maximum likelihood model

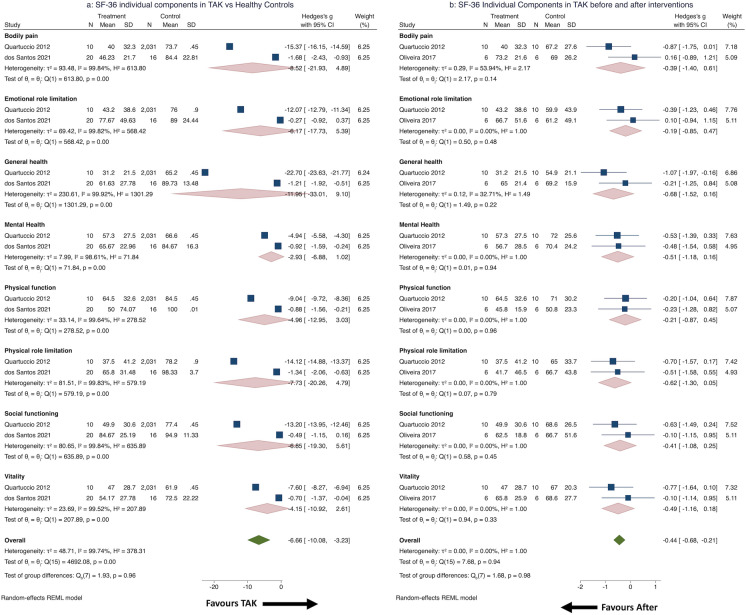

Comparisons between TAK patients and healthy controls were pooled from two studies (one each cross-sectional or cohort studies, 30 patients with TAK) [39, 56]. Large effect sizes denoted worse scores in all domains for patients with TAK, with considerable heterogeneity [32]; however, the differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

SF-36 individual component scores in TAK: comparison with healthy controls and longitudinal changes. a SF-36 individual component scores in patients with TAK compared with healthy controls, b SF-36 individual component scores in patients with TAK before and after therapeutic interventions

Longitudinal changes were pooled from two studies (both cohort, 16 patients with TAK) [39, 45], before and after infliximab [39] or before and after exercise therapy [45]. Effect sizes were small to medium for all domains [32], but not statistically significant, with little observed heterogeneity in domains other than bodily pain (Fig. 3b).

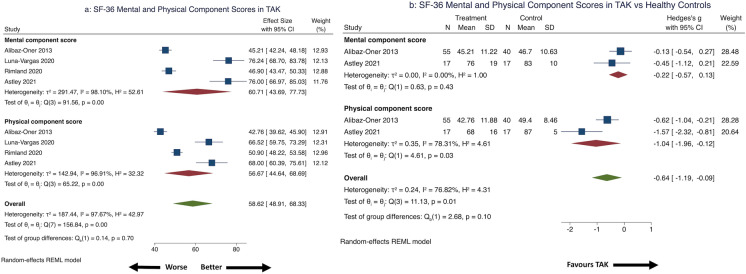

Physical and Mental Component Summary SF-36 Scores

Pooled from four studies (two each cross-sectional or cohort, 153 patients with TAK) [40, 51, 53, 55], the physical component scale score was 56.67 (95% CI 44.64–68.69) and mental component scale score was 60.71 (95% CI 43.69–77.73), with considerable heterogeneity (Fig. 4a) that was not explained by any single study. Sensitivity analyses by study design ameliorated heterogeneity for both the physical component and mental component scales for cross-sectional studies, but only for the mental component scale for cohort studies. Excluding the study using SF-36 version 2 [53] in a secondary analysis, the pooled physical component scale score was 58.80 (95% CI 42.50–75.10) and mental component scale score was 65.48 (95% CI 44.97–86.00).

Fig. 4.

SF-36 physical and mental component summary scores in patients with TAK. a SF-36 summary mental and physical component scores in patients with TAK, b SF-36 summary mental and physical component scores in patients with TAK compared with healthy controls

Comparison with healthy controls were pooled from two studies (72 patients with TAK, 57 healthy controls, one each cross-sectional and cohort) [40, 55]. Effect size was large for the physical component score and small for the mental component scores [32], both favoring worse scores for TAK (statistically significant for physical component score alone). The pooled physical component score had considerable heterogeneity (Fig. 4b). Alibaz-Oner et al. [40] reported no significant changes in the SF-36 physical or mental component scores of 30 patients with TAK over 6 months. Quartuccio et al. [39] reported significant increase in normalized physical component scores (36.9 ± 10.9 before, 44.3 ± 7 after) and non-significant increase in normalized mental component scores (40 + 15 before, 47.7 + 14 after) following infliximab therapy.

Descriptive Results

Akar et al. [38] reported worse SF-36 scores in 51 patients with TAK when compared with 75 healthy controls across all domains; however, the scores were comparable with those for RA or AS. Bodily pain (but not other domains) scored significantly worse for patients with TAK with active disease than for those with inactive disease [38]. Rimland et al. [53] reported similar SF-36 summary physical and mental component scores in 56 patients with TAK or giant cell arteritis (GCA). Yilmaz et al. [42] reported worse SF-36 scores in all domains for 165 patients with TAK compared with 109 healthy controls; with the exception of the domain for mental health, all domains were significantly worse for 71 patients with active TAK compared with 94 patients with inactive TAK. Sreih et al. [43] assessed 207 patients with TAK longitudinally (881 visits with clinical remission, 196 visits with relapse). The physical component score (43.3 ± 10.1 vs. 39 ± 10) but not the mental component scores (46.5 ± 12.3 vs. 47 ± 11) of SF-36 (normalized to North American population) were significantly worse with active disease. Adjusted odds of relapse in the following two visits increased with increment in the physical component score by 1 unit at any visit (odds ratio [OR] 1.07, 95% CI 1.02–1.13) [43]. Gunsay et al. [44] reported that better mental component scores were associated with lesser vascular damage in TAK. Omma et al. [46] reported significantly worse SF-36 scores in all domains except emotional role limitation and summary mental component scores in 165 patients with TAK when compared with 51 healthy controls. Those with resistant TAK (35% of the cohort) had worse scores in all SF-36 domains (except physical function and emotional role limitation) and worse summary physical and mental component scores compared with the rest [46]. Garen et al. [50] reported worse SF-36 scores in six domains in 33 patients with TAK compared with Norwegian standards. Better pain and fatigue were associated with higher mental health scores [50]. Nakaoka et al. [52] assessed SF-36 scores in a RCT of tocilizumab (36 patients with TAK; parallel group, placebo-controlled until 24 weeks, then open-label extension until 96 weeks on tocilizumab). Patients with TAK had worse baseline SF-36 domain scores than the Japanese standard population. There was significant improvement in summary mental component scores of SF-36 from week 12 and in the summary physical component score by week 24 compared with baseline scores (sustained until week 96) with tocilizumab [52].

EuroQol 5-Dimensions

The EQ-5D score assesses QOL across five dimensions, rated across three or five levels, with a visual analog score estimate of overall health ranging from 0 to 100 (higher scores indicating better health) [58]. Two studies reported EQ-5D in patients with TAK. Quartuccio et al. [39] reported significant improvement in EQ-5D scores (derived from SF-36 scores) following infliximab therapy in ten patients with TAK (before 0.57 ± 0.2, after 0.73 ± 0.2). Chen et al. [47] reported improvement in EQ-5D scores in 14 patients with TAK following vascular bypass surgery (before 58.93 + 14.4, after 87.14 + 1.25).

Disability

Health Assessment Questionnaire

The HAQ disability index score is used to measure disability in different disease settings, with scores ranging from 0 to 3 in relation to 12 tasks of daily living. The summary scores are divided by 12 to provide a final score out of 3. Higher scores indicate worse disability [11]. HAQ scores of ≥ 1 indicate significant disability [12]. HAQ scores ≥ 1 indicate significant disability [12].

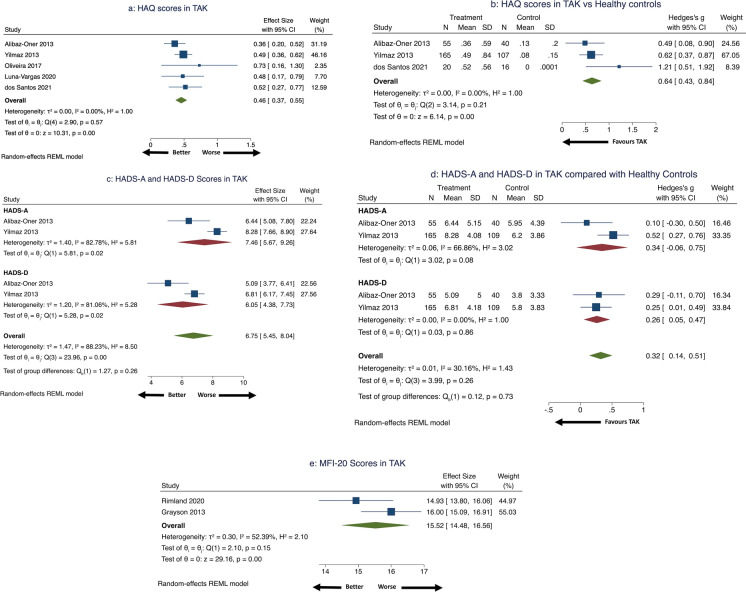

Six studies evaluated HAQ in TAK [40, 42, 45, 49, 51, 56]. Pooled HAQ in 261 patients with TAK (two cohort, three cross-sectional studies) [40, 42, 45, 51, 56] was 0.46 (95% CI 0.37–0.55) with little heterogeneity (Fig. 5a). Three studies (one cohort, two cross-sectional studies) [40, 42, 56] comparing HAQ in 240 patients with TAK with 163 healthy controls identified significantly worse HAQ score in the TAK arm (SMD 0.64, 95% CI 0.43–0.84) (Fig. 5b) with medium effect size [32]. Three studies evaluated longitudinal changes in HAQ. Alibaz-Oner et al. [40] reported similar HAQ for 30 patients with TAK over 6 months. Oliveira et al. [45] reported similar HAQ for six patients with TAK before and after 12 weeks of exercise therapy. Campochiaro et al. [49] reported similar HAQ values at baseline, 6 months and 12 months in 23 patients with TAK after being treated with infliximab biosimilar. This study provided HAQ scores in the range of 3.35 to 3.84 [49]; this was possibly because the authors might have used the original HAQ instead of the HAQ disability index (which provides scores between 0 and 3).

Fig. 5.

HAQ, HADS and MFI-20 scores in patients with TAK. a Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) scores in patients with TAK, b Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) scores in patients with TAK compared with healthy controls, c Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-A and HADS-D, respectively) scores in patients with TAK, d Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) scores in patients with TAK compared with healthy controls, e Multidisciplinary Fatigue Inventory (MFI-20) scores in patients with TAK

International Physical Activity Questionnaire—Short Form

The IPAQ-SF enables assessment of physical activity through seven questions with a subsequent calculation of metabolic equivalents (METs) consumed during such physical activity [60]. dos Santos et al. [56] reported lower physical activity in 20 patients with TAK (mean ± SD: 481.6 ± 379 METs consumed during physical activity per week) compared to 16 healthy controls (1662.7 ± 827.4 METs per week).

Walking Impairment Questionnaire

The WIQ allows self-reporting of walking disability in three domains, namely walking distance, speed of walking and climbing of stairs, on a scale of 0 to 100. Lower scores indicate greater impairment [61]. dos Santos et al. [56] reported worse WIQ scores in 20 patients with TAK (mean ± SD: 64.6 ± 44.5) compared to 16 healthy controls (96.3 ± 8.2).

Work Productivity and Activity Impairment

The WPAI scale assesses work productivity in four domains, with higher scores indicating worse work impairment status [62]. Erdal et al. [57] reported worse scores in the domain of daily activity impairment in individuals with active TAK when compared with those with inactive disease. Both disease activity and depression (measured using HADS-D) mediated the effect on this domain of the WPAI.

Mood Abnormalities

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Score

The HADS assesses the likelihood of anxiety (through the HADS-A questionnaire) and depression (via the HADS-D questionnaire) in respondents. Each questionnaire comprises seven questions, rated between 0 and 3, for a total score of 21 each. Scores of eight or above indicate a greater probability of anxiety (for the HADS-A) or depression (for the HADS-D) [13].

Three studies reported HADS in TAK [40, 42, 57]. Two studies provided comparisons with healthy controls [40, 42]. Data were pooled from two studies (one each cross-sectional and cohort; 220 patients with TAK) [40, 42]. Pooled HADS-A was 7.46 (95% CI 5.67–9.26) and pooled HADS-D was 6.05 (95% CI 4.38–7.73) with significant heterogeneity (Fig. 5c). Comparing 220 patients with TAK with 149 healthy controls revealed significantly higher HADS-D (SMD 0.26, 95% CI 0.05–0.47 without heterogeneity) but not HADS-A (SMD 0.34, 95% CI − 0.06 to 0.75 with considerable heterogeneity) in TAK (Fig. 5d) with a small effect size [32]. Erdal et al. reported higher HADS-A [mean (SD) 10.5 (5.25) versus 6.5 (4)] and HADS-D [8 (4.75) versus 5 (3.25)] in 26 active TAK compared to 50 with inactive TAK [57].

Fatigue

Multidisciplinary Fatigue Inventory

The MFI-20 assesses fatigue using 20 questions scored from 0 to 5, averaged to provide a score from 20, with higher scores indicating worse fatigue [59]. Three studies assessed MFI-20 in TAK [41, 51, 53]. Pooled MFI-20 score in 113 patients with TAK (one each cross-sectional and cohort study) [41, 53] was 15.52 (95% CI 14.48–16.56) denoting significant fatigue (MFI-20 > 13) [41] with considerable heterogeneity (Fig. 5e). Grayson et al. [41] reported similar MFI-20 scores in patients with TAK when compared with those with AAV, GCA, IgA vasculitis, polyarteritis nodosa and primary central nervous system angiitis. Rimland et al. [53] reported similar MFI-20 scores in patients with TAK and GCA. Luna-Vargas et al. [51] reported the association of earlier disease duration with worse general fatigue domain scores of MFI-20 in 15 patients with TAK.

Perceptions of Illness

Illness Perception Questionnaire and Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire

The IPQ-R and its modification the BIPQ help assess the perceptions of patients towards their disease. The IPQ-R assesses patient perceptions in eight dimensions, namely identity, consequences of disease, timeline (acute/chronic), timeline (cyclical), personal control, treatment control, emotional representations and illness coherence [63]. The BIPQ was developed as a modification of the IPQ-R to assess perceptions about illness in eight domains, four of which are in common with the IPQ-R (identity, consequences of disease, personal control, treatment control) and four others (timeline, concern, understanding and emotional response), each with a single question rated from 0 to 10. A further question assesses perceptions regarding the cause of illness in an open-ended manner [64].

Grayson et al. [41] reported IPQ-R scores in 692 subjects with vasculitis (57 with TAK). They noted worse perceptions of illness with respect to the dimensions of identity, timeline (acute/chronic) and illness consequences in TAK patients. Worse perceptions of illness were pervasive across different forms of vasculitis. When compared with patients with other chronic diseases (diabetes melllitus, hypertension, osteoarthritis and systemic sclerosis), those with vasculitis had worse scores on the dimensions of consequences and emotional representations. Younger age (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.02–1.06), depression (OR 4.94, 95% CI 2.9–8.41) and active disease (OR 2.05, 95% CI 1.27–3.29) were associated with worse disease perception [41]. Erdal et al. [57] reported a significant association of scores on the consequences domain of IPQ-R with active disease in 77 patients with TAK. They also identified depression (measured using HADS-D score) as a likely mediator of worse disease perceptions in the consequences domain amongst patients with active TAK [57].

Two cohort studies assessed BIPQ in 103 patients with TAK [53, 54]. Rimland et al. [53] reported mean BIPQ score of 42.6 ± 11.26 (imputed mean with SD) and Schwartz et al. [54] reported BIPQ of 38.4 ± 14.5 (mean with SD) in patients with TAK. Rimland et al. reported similar BIPQ scores in patients with TAK and GCA [53]. Schwartz et al. compared BIPQ scores in different systemic vasculitides. Scores for TAK were highest for the timeline domain and lowest for the domains of personal control and identity. BIPQ scores for TAK were similar to GCA or AAV but worse than those for relapsing polychondritis [54].

Nottingham Health Profile

The NHP assesses the distress of patients in six domains (energy levels, emotional reactions, physical mobility, pain, social isolation and sleep). Higher scores indicate greater distress [65]. Akar et al. [38] reported higher scores in the energy level, physical mobility and pain domains of the NHP for patients with TAK when compared with healthy controls. When compared with patients with RA or AS, those with TAK had comparable NHP scores in most domains other than pain, which was better than the scores for RA [38].

Fibromyalgia

The 2010 ACR diagnostic criteria define fibromyalgia using the WPI and the Symptom Severity Scale (SSS) as persistent pain in patients for at least 3 months without any suitable alternative explanation. The WPI assesses pain in 19 areas of the body, and the SSS assesses the severity of four symptoms, namely fatigue, waking unrefreshed, cognitive symptoms and somatic symptoms, each on a scale of 0–3, with higher scores indicating greater severity. In an individual with duration of symptoms for at least 3 months without a suitable alternative explanation, fibromyalgia can be diagnosed with an WPI score of at least 7 and an SSS score of at least 5, or an WPI score between 3 and 6 and an SSS score of at least 9 [66]. Alibaz-Oner et al. [40] reported fibromyalgia in seven of 55 patients with TAK using the 2010 ACR criteria and in three of 55 patients with TAK using the 1990 ACR criteria, with similar prevalence to the general population. Active TAK was associated with a significantly greater risk of prevalent fibromyalgia than inactive TAK (risk ratio 9.71, 95% CI 1.26–75.15) [40].

Developing a PROM Specific to TAK

A qualitative study by OMERACT reported aspects prioritized by patients with TAK after in-depth interviews with 31 patients from Turkey and the USA. Eleven domains were common between patients from both countries, including impact on various situations at home or work, coping behavior, anxiety, depression, disability in daily activities due to reduced functional capacity, psychological support and social support. These findings might enable the development of a PROM specific to TAK [48].

Certainty of Evidence for Pooled Outcomes

The certainty of evidence for comparisons of QOL, disability, anxiety and depression between TAK and healthy controls ranged from low to very low (ESM Table S8).

Discussion

The present systematic review revealed worse QOL, greater depression and anxiety scores and worse disability in patients with TAK when compared to healthy controls. Fewer studies evaluated changes in PROMs over time or the relationship with disease activity. QOL remained stable or improved with time or following specific treatments in TAK. Disability remained similar over time or after treatment. QOL, depression and work impairment were worse in patients with TAK with active disease when compared with those with inactive disease. Identified studies were of moderate to high quality. Wherever outcomes could be pooled, the certainty of evidence was low to very low. However, it must be emphasized that few studies assessed PROMs in patients with TAK in comparison with healthy controls, or assessed longitudinal changes. Many of the pooled outcomes were heterogenous and, therefore, should be cautiously interpreted. The findings of the systematic review along with the identified knowledge gaps about PROMs in TAK are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of findings from the systematic review on patient-reported outcome measures in patients with TAK

| PROM | Comparison with healthy controls | Changes over time | Comparison between patients with active and inactive disease |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of life | |||

| SF-36 | Worse in TAK* | Stable or better with time | Worse in active TAK* |

| Improvement following exercise therapy or infliximab | |||

| EQ-5D | – | Improve following infliximab or vascular bypass surgery | – |

| Disability | |||

| HAQ | Worse in TAK* | Stable over time/following exercise therapy/following infliximab | – |

| IPAQ-SF | Lesser physical activity in TAK* | – | – |

| WIQ | Worse in TAK* | – | – |

| WPAI | – | – | Greater work impairment in those with active disease* |

| Mood | |||

| Anxiety (HADS-A) | Worse in TAK | – | Worse in active TAK* |

| Depression (HADS-D) | Worse in TAK* | – | Worse in active TAK* |

| Fatigue | |||

| MFI-20 | – | – | – |

| Perceptions of illness | |||

| IPQ-R | – | – | – |

| BIPQ | – | – | – |

| NHP | Worse in TAK* | – | – |

| Fibromyalgia | |||

| Diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia | Similar prevalence in TAK and HC | – | Active TAK associated with greater risk of prevalent fibromyalgia* |

PROM Patient-reported outcome measure

*Significant difference at the 5% level between comparisons

Previous systematic reviews have reported impaired QOL in other inflammatory rheumatic diseases, such as RA [67], AS [68], systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [69] and systemic sclerosis (SSc) [70]. While active disease associates with worse QOL in AS [68], this is less clear for other rheumatic diseases. Longer duration of RA is associated with better SF-36 scores [67], possibly reflecting better adjustment to disease with time or better control of active disease. Patients with RA have worse HAQ scores which improve following control of disease activity and worsen with longer disease duration [71]. Depression is more prevalent in patients with RA [72], AS [73, 74] and SSc [75] and is associated with worse pain in RA. Risk of developing incident RA is higher in those with depression [76]. Up to one half of patients with SLE [77, 78] and SSc experience work disability [79]. Work disability in the setting of RA [80], AS [81] and SSc [79] is multifactorial, related to disease and socio-behavioral aspects. The current systematic review is the first to highlight worse PROMs in patients with TAK, akin to other systemic vasculitides [53, 54]. Factors determining PROMs in TAK require further exploration via qualitative research.

The present systematic review has a number of limitations. Relatively fewer studies (many with small sample sizes) have evaluated PROMs in TAK. However, this is a limitation of TAK studies in general and must be viewed in the context of the rarity of the disease. Paucity of identified studies did not permit assessment of publication bias. Pooled outcomes had considerable statistical heterogeneity, possibly due to the small sample size of individual studies [33]; this heterogeneity was partially explained by excluding findings from individual studies. Searching across multiple databases and sources of information to identify relevant studies and reasonable study quality were strengths of our systematic review.

This systematic review has identified research gaps about PROMs in TAK. Hardly any studies assessed PROMs in TAK from Asia, where the disease is relatively more common [4]. Few studies have reported longitudinal changes in PROMs in TAK, changes following treatment or PROMs in childhood-onset TAK. Previous reviews (and this one) have identified the paucity of studies assessing the impact of pharmacotherapy on QOL in LVV [82]. The development of a specific PROM for TAK is underway; however, this effort represents perspectives from patients with TAK from restricted geographic locations (Turkey and USA) [48]. Such a PROM shall require validation across different populations. There might even be a need to develop a specific PROM for TAK from different geographic regions, taking into consideration socio-cultural diversities across the world. While studies have used the generic HAQ disability index (also validated in TAK [42]), this tool had originally been designed for patients with arthritides such as RA and osteoarthritis [83]. Inclusion of clinical features, such as limb claudication, neck pain and breathlessness due to heart failure, might enhance the representativeness of the HAQ in TAK.

Conclusions

To conclude, the present systematic review uncovers reasonable evidence for worse disability and depression in patients with TAK compared with healthy controls. Patients with active TAK have worse QOL, mood and disability than those with inactive TAK. There exists an unmet need to longitudinally assess changes in PROMs in TAK (particularly following therapy) and to develop and validate a TAK-specific PROM.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding was received for the publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authors’ Contributions

DPM, VA, AS conceived and designed the study; DPM, UR and PP prepared the material and collected and analyzed the data; DPM performed the statistical analysis; DPM, UR and PP wrote the first draft; VA and AS criticially revised the first draft for important intellectual content. All authors (DPM, UR, PP, VA, AS) approved the final version to be submitted. All authors (DPM, UR, PP, VA, AS) aggree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Prior Presentation

The data reported in this manuscript have not been presented previously.

Disclosures

Durga Prasanna Misra has nothing to disclose. Upendra Rathore has nothing to disclose. Pallavi Patro has nothing to disclose. Vikas Agarwal has nothing to disclose. Aman Sharma has nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

All the analyses performed for this systematic review have been reported in the main text or in the supplementary files. The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author (Durga Prasanna Misra, durgapmisra@gmail.com ) on reasonable request.

Footnotes

Durga P. Misra and Upendra Rathore are joint first authors.

Contributor Information

Durga P. Misra, Email: dpmisra@sgpgi.ac.in, Email: durgapmisra@gmail.com

Upendra Rathore, Email: upen0007@gmail.com.

Pallavi Patro, Email: patropallavi17@gmail.com.

Vikas Agarwal, Email: vikasagr@yahoo.com, Email: vikasagr@sgpgi.ac.in.

Aman Sharma, Email: amansharma74@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Nikiphorou E, Nurmohamed MT, Szekanecz Z. Editorial: Comorbidity burden in rheumatic diseases. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:197. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dougados M, Soubrier M, Antunez A, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities in rheumatoid arthritis and evaluation of their monitoring: results of an international, cross-sectional study (COMORA) Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):62. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aydin SZ, Robson JC, Sreih AG, et al. Update on outcome measure development in large-vessel vasculitis: report from OMERACT 2018. J Rheumatol. 2019;46(9):1198–1201. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.181072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Misra DP, Wakhlu A, Agarwal V, Danda D. Recent advances in the management of Takayasu arteritis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019;22(Suppl 1):60–68. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weldring T, Smith SMS. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) Health Serv Insights. 2013;6:61–68. doi: 10.4137/HSI.S11093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pincus T, Sokka T. Can a Multi-Dimensional Health Assessment Questionnaire (MDHAQ) and Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data (RAPID) scores be informative in patients with all rheumatic diseases? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21(4):733–753. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merkel PA, Herlyn K, Mahr AD, et al. Progress towards a core set of outcome measures in small-vessel vasculitis. Report from OMERACT 9. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(10):2362–2368. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aydin SZ, Direskeneli H, Sreih A, Alibaz-Oner F, Gul A, Kamali S, et al. Update on outcome measure development for large vessel vasculitis: report from OMERACT 12. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(12):2465–2469. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robson JC, Dawson J, Doll H, Cronholm PF, Milman N, Kellom K, et al. Validation of the ANCA-associated vasculitis patient-reported outcomes (AAV-PRO) questionnaire. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(8):1157–1164. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lins L, Carvalho FM. SF-36 total score as a single measure of health-related quality of life: scoping review. SAGE Open Med. 2016;4:2050312116671725. doi: 10.1177/2050312116671725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruce B, Fries JF. The Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23(5 Suppl 39):S14–S18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sokka T, Krishnan E, Häkkinen A, Hannonen P. Functional disability in rheumatoid arthritis patients compared with a community population in Finland. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(1):59–63. doi: 10.1002/art.10731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:29. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al., editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 2. Chichester: Wiley; 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rethlefsen ML, Kirtley S, Waffenschmidt S, et al. PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s13643-020-01542-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arend WP, Michel BA, Bloch DA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(8):1129–1134. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishikawa K. Diagnostic approach and proposed criteria for the clinical diagnosis of Takayasu's arteriopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;12(4):964–972. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(88)90462-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma BK, Jain S, Suri S, Numano F. Diagnostic criteria for Takayasu arteritis. Int J Cardiol. 1996;54(Suppl):S141–S147. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5273(96)88783-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 revised international Chapel Hill consensus conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(1):1–11. doi: 10.1002/art.37715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ozen S, Pistorio A, Iusan SM, et al. EULAR/PRINTO/PRES criteria for Henoch-Schönlein purpura, childhood polyarteritis nodosa, childhood Wegener granulomatosis and childhood Takayasu arteritis: Ankara 2008. Part II: Final classification criteria. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(5):798–806. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.116657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Misra DP, Rathore U, Patro P, Agarwal V, Sharma A. Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs for the management of Takayasu arteritis—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10067-021-05743-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pittam B, Gupta S, Ahmed AE, Hughes DM, Zhao SS. The prevalence and impact of depression in primary systemic vasculitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int. 2020;40(8):1215–1221. doi: 10.1007/s00296-020-04611-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 11 Aug 2021.

- 27.The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). The Joanna Briggs Institute checklist for analytical cross sectional studies. https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Analytical_Cross_Sectional_Studies2017_0.pdf. Accessed 16 Apr 2021.

- 28.Lin L, Chu H. Quantifying publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2018;74(3):785–794. doi: 10.1111/biom.12817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Misra DP, Agarwal V. Systematic reviews: challenges for their justification, related comprehensive searches, and implications. J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33(12):9. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Method. 2014;14:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Method. 2005;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lakens D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front Psychol. 2013;4:863. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.IntHout J, Ioannidis JPA, Borm GF, Goeman JJ. Small studies are more heterogeneous than large ones: a meta-meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(8):860–869. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brunner J, Feldman BM, Tyrrell PN, Kuemmerle-Deschner JB, Zimmerhackl LB, Gassner I, et al. Takayasu arteritis in children and adolescents. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49(10):1806–1814. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Misra DP, Aggarwal A, Lawrence A, Agarwal V, Misra R. Pediatric-onset Takayasu's arteritis: clinical features and short-term outcome. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35(10):1701–1706. doi: 10.1007/s00296-015-3272-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.GRADEPro GDT. GRADEpro guideline development tool. 2020. Hamilton: McMaster University (developed by Evidence Prime, Inc.). Available from https://gradepro.org/.

- 37.Abularrage CJ, Slidell MB, Sidawy AN, Kreishman P, Amdur RL, Arora S. Quality of life of patients with Takayasu's arteritis. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47(1):131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akar S, Can G, Binicier O, Solmaz D, et al. Quality of life in patients with Takayasu's arteritis is impaired and comparable with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27(7):859–865. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0813-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quartuccio L, Schiavon F, Zuliani F, et al. Long-term efficacy and improvement of health-related quality of life in patients with Takayasu's arteritis treated with infliximab. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30(6):922–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alibaz-Oner F, Can M, İlhan B, Polat Ö, Mumcu G, Direskeneli H. Presence of fibromyalgia in patients with Takayasu's arteritis. Intern Med. 2013;52(24):2739–2742. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.52.0848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grayson PC, Amudala NA, McAlear CA, et al. Illness perceptions and fatigue in systemic vasculitis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65(11):1835–1843. doi: 10.1002/acr.22069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yilmaz N, Can M, Oner FA, et al. Impaired quality of life, disability and mental health in Takayasu's arteritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52(10):1898–1904. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sreih AG, Kermani TA, Tomasson G, et al. The utility of patient-reported outcomes in predicting disease activity in patients with Takayasu's arteritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:2. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gunsay GC, Unal AU, Oner FA, Direskeneli H, et al. P1_21 Damage assessment in Takayasu arteritis: Disease-related damage is more prominent. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017;56(Suppl 3):iii50. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oliveira DS, Shinjo SK, Silva MG, et al. Exercise in Takayasu arteritis: effects on inflammatory and angiogenic factors and disease-related symptoms. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017;69(6):892–902. doi: 10.1002/acr.23011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Omma A, Erer B, Karadag O, et al. Remarkable damage along with poor quality of life in Takayasu arteritis: cross-sectional results of a long-term followed-up multicentre cohort. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017;35(1):S77–S82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen ZGG, Chen YXX, Diao YPP, et al. Simultaneous multi-supra-aortic artery bypass successfully implemented in 17 patients with type I Takayasu arteritis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2018;56(6):903–909. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2018.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sreih AG, Alibaz-Oner F, Easley E, et al. Health-related outcomes of importance to patients with Takayasu’s arteritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2018;36:S51–S57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Campochiaro C, Tomelleri A, Sartorelli S, et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximabbiosimilar in takayasu arteritis (takasim): a monocentric, observational, prospective, open-label study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(Suppl 1):1531. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garen T, Palm O, Gudbrandsson B. Impaired health-related quality of life and physical function in Norwegian patients with Takayasu arteritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:1274. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-eular.3595. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luna-Vargas L, Hinojosa CA, Contreras-Yáñez I, Anaya-Ayala JE, Hinojosa-Azaola A. Takayasu's arteritis from the patients' perspectives: measuring the pulse to the patient-reported outcomes. Ann Vasc Surg 2021;73:314–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Nakaoka Y, Isobe M, Tanaka Y, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in refractory Takayasu arteritis: final results of the randomized controlled phase 3 TAKT study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020;59(9):2427–2434. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rimland CA, Quinn KA, Rosenblum JS, et al. Outcome measures in large vessel vasculitis: relationship between patient-, physician-, imaging-, and laboratory-based assessments. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2020;72(9):1296–1304. doi: 10.1002/acr.24117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schwartz MN, Rimland CA, Quinn KA, et al. Utility of the brief illness perception questionnaire to monitor patient beliefs in systemic vasculitis. J Rheumatol. 2020;47(12):1785–1792. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.190828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Astley C, Gil S, Clemente G, et al. Poor physical activity levels and cardiorespiratory fitness among patients with childhood-onset takayasu arteritis in remission: a cross‐sectional, multicenter study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2021;19:39. 10.1186/s12969-021-00519-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.dos Santos AM, Misse RG, Borges IBP, et al. Increased modifiable cardiovascular risk factors in patients with Takayasu arteritis: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Adv Rheumatol 2021;61:1. 10.1186/s42358-020-00157-1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Erdal S, Nalbantoğlu B, Gür MB, et al. HADS-depression score is a mediator for illness perception and daily life impairment in Takayasu's arteritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10067-021-05719-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brooks R, Boye KS, Slaap B. EQ-5D: a plea for accurate nomenclature. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2020;4(1):52. doi: 10.1186/s41687-020-00222-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smets EM, Garssen B, Bonke B, De Haes JC. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39(3):315–325. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)00125-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee PH, Macfarlane DJ, Lam TH, Stewart SM. Validity of the international physical activity questionnaire short form (IPAQ-SF): a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8(1):115. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jain A, Liu K, Ferrucci L, et al. The Walking Impairment Questionnaire stair-climbing score predicts mortality in men and women with peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55(6):1662–73.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang W, Bansback N, Boonen A, Young A, Singh A, Anis AH. Validity of the work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire–general health version in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(5):R177-R. doi: 10.1186/ar3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moss-Morris R, Weinman J, Petrie K, Horne R, Cameron L, Buick D. The revised Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ-R) Psychol Health. 2002;17(1):1–16. doi: 10.1080/08870440290001494. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Main J, Weinman J. The brief illness Perception Questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60(6):631–637. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wiklund I. The Nottingham Health Profile–a measure of health-related quality of life. Scand J Prim Health Care Suppl. 1990;1:15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62(5):600–610. doi: 10.1002/acr.20140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Matcham F, Scott IC, Rayner L, et al. The impact of rheumatoid arthritis on quality-of-life assessed using the SF-36: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;44(2):123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang X, Fan D, Xia Q, et al. The health-related quality of life of ankylosing spondylitis patients assessed by SF-36: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(11):2711–2723. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1345-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gu M, Cheng Q, Wang X, et al. The impact of SLE on health-related quality of life assessed with SF-36: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Lupus. 2019;28(3):371–382. doi: 10.1177/0961203319828519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li L, Cui Y, Chen S, et al. The impact of systemic sclerosis on health-related quality of life assessed by SF-36: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2018;21(11):1884–1893. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pollard L, Choy EH, Scott DL. The consequences of rheumatoid arthritis: quality of life measures in the individual patient. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23(5 Suppl 39):S43–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dickens C, McGowan L, Clark-Carter D, Creed F. Depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(1):52–60. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Park JY, Howren AM, Zusman EZ, Esdaile JM, De Vera MA. The incidence of depression and anxiety in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Rheumatol. 2020;4:12. doi: 10.1186/s41927-019-0111-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang L, Wu Y, Liu S, Zhu W. Prevalence of depression in ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Investig. 2019;16(8):565–574. doi: 10.30773/pi.2019.06.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thombs BD, Taillefer SS, Hudson M, Baron M. Depression in patients with systemic sclerosis: a systematic review of the evidence. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(6):1089–1097. doi: 10.1002/art.22910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vallerand IA, Patten SB, Barnabe C. Depression and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2019;31(3):279–284. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Baker K, Pope J. Employment and work disability in systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48(3):281–284. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Scofield L, Reinlib L, Alarcón GS, Cooper GS. Employment and disability issues in systemic lupus erythematosus: a review. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(10):1475–1479. doi: 10.1002/art.24113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sharif R, Mayes MD, Nicassio PM, et al. Determinants of work disability in patients with systemic sclerosis: a longitudinal study of the GENISOS cohort. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41(1):38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.de Croon EM, Sluiter JK, Nijssen TF, Dijkmans BA, Lankhorst GJ, Frings-Dresen MH. Predictive factors of work disability in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(11):1362–1367. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.020115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cakar E, Taskaynatan MA, Dincer U, Kiralp MZ, Durmus O, Ozgül A. Work disability in ankylosing spondylitis: differences among working and work-disabled patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28(11):1309–1314. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1249-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Misra DP, Sharma A, Kadhiravan T, Negi VS. A scoping review of the use of non-biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in the management of large vessel vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16(2):179–191. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2016.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bruce B, Fries JF. The Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire: a review of its history, issues, progress, and documentation. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(1):167–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the analyses performed for this systematic review have been reported in the main text or in the supplementary files. The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author (Durga Prasanna Misra, durgapmisra@gmail.com ) on reasonable request.