Abstract

Objectives

To compare the accuracy of coronary calcium quantification of cadaveric specimens imaged from a photon-counting detector (PCD)-CT and an energy-integrating detector (EID)-CT.

Methods

Excised coronary specimens were scanned on a PCD-CT scanner, using both the PCD and EID subsystems. The scanning and reconstruction parameters for EID-CT and PCD-CT were matched: 120 kV, 9.3–9.4 mGy CTDIvol, and a quantitative kernel (D50). PCD-CT images were also reconstructed using a sharper kernel (D60). Scanning the same specimens using micro-CT served as a reference standard for calcified volumes. Calcifications were segmented with a half-maximum thresholding technique. Segmented calcified volume differences were analyzed using the Friedman test and post hoc pairwise Wilcoxon signed rank test with the Bonferroni correction. Image noise measurements were compared between EID-CT and PCD-CT with a repeated-measures ANOVA test and post hoc pairwise comparison with the Bonferroni correction. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The volume measurements in 12/13 calcifications followed a similar trend: EID-D50 > PCD-D50 > PCD-D60 > micro-CT. The median calcified volumes in EID-D50, PCD-D50, PCD-D60, and micro-CT were 22.1 (IQR 10.2–64.8), 21.0 (IQR 9.0–56.5), 18.2 (IQR 8.3–49.3), and 14.6 (IQR 5.1–42.4) mm3, respectively (p < 0.05 for all pairwise comparisons). The average image noise in EID-D50, PCD-D50, and PCD-D60 was 60.4 (± 3.5), 56.0 (± 4.2), and 113.6 (± 8.5) HU, respectively (p < 0.01 for all pairwise comparisons).

Conclusion

The PCT-CT system quantified coronary calcifications more accurately than EID-CT, and a sharp PCD-CT kernel further improved the accuracy. The PCD-CT images exhibited lower noise than the EID-CT images.

Keywords: X-ray tomography, Coronary artery disease, Cadaver, Artifacts

Introduction

Cardiovascular (CV) disease, in general, and coronary artery disease (CAD), in particular, are the most common causes of death worldwide [1]. The presence of coronary artery calcifications (CAC) is a specific marker of CAD, and the amount of CAC is shown to be proportional to the CAD severity [2, 3]. Also, the extent of CAC is an important predictor of future CV risk [4, 5]. Computed tomography (CT) is an established modality for CAC imaging [6] and is commonly performed using calcium scoring computed tomography (CSCT) [5–8], coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) [6, 8, 9], and non-contrast, non-gated chest CT (NCCT) [10].

A CSCT is performed on asymptomatic patients to predict the risk of future CV events [4, 7, 8], using quantitative calcium scoring techniques, e.g., the Agatston score [11]. A CCTA is performed in symptomatic patients to assess CAC and coronary non-calcified plaques [6, 8, 9]. A CCTA has an excellent sensitivity to detect obstructive CAD, but the specificity is moderate [12]. A NCCT is performed for several scan indications. The Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography and the Society of Thoracic Radiology recommend a CAC evaluation to be performed in all NCCT scans [10].

Clinical CT scanners are equipped with energy-integrating detectors (EIDs), which utilize scintillators to generate visible light that is converted to an electric signal proportional to the total energy deposited by all incident photons. The EID pixel size and its supported resolution are limited by separating septa between detector cells, necessary to prevent signal leakage (cross-talk) between adjacent detectors elements. The limited spatial resolution in EID-CT scanners leads to partial volume averaging (PVA) if tissues with heterogeneous attenuation are encompassed in one voxel [13]. When PVA causes CAC overestimation, it is referred to as calcium blooming artifacts (CBA) [14]. For small- and low-density CAC, the PVA may result in CAC underestimation, especially when the CT number of affected calcium drops below the threshold (e.g., 130 HU in Agatston score). In CSCT, the accuracy of the Agatston score is affected by PVA around calcifications [15–17], which contributes to inter-scan variability [18, 19]. Similar limitations impact NCCT scans [20]. In CCTA, CBA causes CAD overestimation, which limits specificity [21, 22].

In contrast to the EID technology, photon-counting detectors (PCDs) use a semiconductor to directly convert individual x-ray photons into electrical signals, which removes the need for a scintillation layer and separating septa. The PCD elements can therefore be made smaller, without compromising geometric efficiency (fill factor) [23]. Pixel sizes as small as 0.25 mm (at the isocenter of CT gantry) can be enabled using PCD technology (compared with 0.5–0.6 mm pixel size for EIDs), thereby improving spatial resolution for ultra-high-resolution (UHR) imaging [24].

The high-resolution benefits of PCD-CT [23–26] have been previously reported, but not in the context of reducing CBA. The aim of this study was to compare the accuracy of coronary calcification quantification from cadaveric specimens, imaged with a PCD-CT and an EID-CT, using measurements from micro-CT as the reference standard.

Materials and methods

Coronary specimens’ preparation

With the approval of the institutional biospecimens committee (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA), a total of six coronary arteries and one coronary venous graft were excised from three human cadavers, subsequently fixed in neutral-buffered formalin, and separately embedded in methyl methacrylate (MMA).

PCD-CT and EID-CT image acquisition and reconstruction

The coronary specimens were placed within a 30-cm (lateral width) water tank and scanned on a research PCD-CT (SOMATOM CounT; Siemens Healthcare GmbH). The PCD-CT scanner was built on a modified second-generation dual-source CT scanner platform (SOMATOM Definition Flash; Siemens Healthcare GmbH), with two subsystems, one EID and one PCD, operated independently. The specimens were identically scanned from end-to-end using both the EID and PCD subsystems. The scan field of view (FOV) of the EID-CT and PCD-CT subsystems is 50 and 27.5 cm, respectively. Due to the limited FOV in the PCD-CT subsystem, a data completion scan using the EID-CT subsystem is needed for objects larger than 27.5 cm. Four modes of detector operation are available on the PCD-CT subsystem (macro mode, chess mode, UHR mode, and sharp mode), which use between 2 and 4 energy thresholds. Details of the PCD-CT scanner have been previously described elsewhere [27–29].

The EID-CT and PCD-CT scans were performed using spiral-scan protocols at a tube potential of 120 kV. The radiation dose used was matched as close as possible, with a volume CT dose index (CTDIvol) of 9.3 and 9.4 mGy, respectively. The PCT-CT scan was performed using the sharp acquisition mode, which included a collimation of 48 × 0.25 mm, energy threshold settings of 25 and 65 keV, and effective detector pixel sizes of 0.25 and 0.5 mm for the low and high energy thresholds respectively. Sharp mode was chosen over UHR mode due to the availability of 0.5-s rotation time and larger z-coverage (12 mm). The low energy threshold images (25–120 keV, 0.25 mm effective detector pixel size similar to UHR mode) were used in our image analysis. Reconstructions were performed with the vendor-provided weighted filtered back projection (WFBP) technique [30], using sharp quantitative kernels. The EID-CT and PCD-CT data were both reconstructed with a D50 kernel. In addition, the PCD-CT data were reconstructed with a sharper D60 kernel, which was not available for the EID-CT data. For brevity, these three CT reconstructed image sets will henceforth be referred to as “EID-D50,” “PCD-D50,” and “PCD-D60.” The reconstruction parameters for EID-CT and PCD-CT were matched, including a slice thickness of 1 mm, FOV of 120 mm, and voxel dimensions of 0.23 × 0.23 × 1 mm. Further details about the acquisition and reconstruction parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

CT acquisition and reconstruction parameters for EID-CT and PCD-CT scans

| CT system | EID-CT | PCD-CT |

|---|---|---|

| Scanner platform | SOMATOM Definition Flash | SOMATOM CounT |

| Scan mode | Spiral | Spiral |

| CTDIvol (mGy) | 9.3 | 9.4 |

| Tube potential (kV) | 120 | 120 |

| Tube current-time product (mAs) | 138 | 116 |

| Pitch | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Collimation (mm) | 128 × 0.6 | 48 × 0.25 |

| Rotation time (s) | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Energy thresholds (keV) | N/A | 25/65 |

| Reconstruction technique | WFBP | WFBP |

| Kernel | D50 | D50, D60 |

| Slice thickness (mm) | 1 | 1 |

| Increment (mm) | 1 | 1 |

| Reconstruction field of view (mm) | 120 | 120 |

| Image matrix size | 512 × 512 | 512 × 512 |

CT, computed tomography; EID, energy-integrating detector; PCD, photon-counting detector; CTDIvol, volume CT dose index; WFBP, weighted filtered back projection

Micro-CT image acquisition and reconstruction

The coronary specimens were individually imaged on a custom-built micro-CT scanner (Mayo Clinic X-Ray Imaging Core), equipped with a microfocus x-ray source (PANalytical B.V.) with a molybdenum x-ray anode and an external zirconium filter to obtain a near monochromatic spectrum centered around 17 keV. The images were acquired using a Pixis-XB detector (Pixis-XB: 1300, Princeton Instruments) which possessed a CsI scintillator and Tb Fiber optic plate to detect incident x-rays and pixels of pitch 0.02 × 0.02 mm. A total of 721 projection images were acquired over 360° of specimen rotation. Reconstructions were performed with a Feldkamp filtered back projection algorithm and produced images with voxel dimensions of 0.02 × 0.02 × 0.02 mm.

Sample inclusions

A thoracic radiologist (M.S., 11 years’ experience in cardiac CT) reviewed all the EID-CT, PCD-CT, and micro-CT images. A total of 7 coronary vessels from the three cadavers resulted in 13 included calcifications. In total, 12/13 calcifications were derived from native coronary arteries and 1/13 from a coronary venous graft calcification. The graft calcification may have another pathogenesis than the native calcifications [31], but was morphologically similar.

Coronary calcification volume quantification

The 13 calcifications were segmented and volumetrically compared across the four reconstructed image sets (EID-D50, PCD-D50, PCD-D60, and micro-CT). All calcifications were segmented using a half-maximum thresholding (HMT) technique [32] to identify their external boundaries. The HMT value represented the midpoint between the background MMA attenuation and the calcification’s attenuation, which yields a representative boundary between the two materials.

In the four reconstructed image sets, the mean attenuation value of the central calcification and the MMA was determined image-by-image by the use of circular region of interests (ROIs). In the EID and PCD-CT reconstructions, the ROI positions were initially identified in the PCD-D50 images and then positioned identically in the EID-D50 and PCD-D60 images. The PCD-D50 image set was selected to represent the ROI locations due to its images being found to exhibit the least noise. The image attenuation values were expressed as Hounsfield units for the EID and PCD-CT image sets and linear attenuation coefficients for the micro-CT image set. All ROI positions were identified using the ImageJ software [33].

The volumetric computations for all 13 calcifications in the four reconstructed image sets were performed using an in-house Matlab algorithm (MATLAB, year 2018, Version b: The MathWorks Inc.). The algorithm calculated each calcification’s HMT on an image-by-image basis using the ROI positions defined previously. For each image, any voxels within the calcification exceeding the HMT were counted as part of its total area. To determine the ultimate volume of each calcification, the segmented areas in all corresponding images were summated. The calcification’s volume in voxels was then converted to mm3 using the voxel dimensions noted previously. The segmented volume measurements corresponding to the 13 calcifications were finally compared among the four reconstructed image sets.

In 5/170 (2.9%) separately located EID-CT and/or PCD-CT images, the calcification was too small for adequate attenuation measurements. For those images, the adjacent image’s HMT was applied for segmentation instead. Any part of a calcification too small for attenuation measurements in > 1 contiguous image was not included.

Image noise measurements

Image noise was derived from the CT number standard deviation (SD) measured within the background water of the 30-cm water tank. A circular ROI with a diameter of 100 voxels (23.4 mm) was applied to measure image noise in all EID-D50, PCD-D50, and PCD-D60 CT image sets (n = 258 images per image set).

Morphological description

One radiologist (M.S.) reviewed the calcifications morphological features, which were organized into three classes, each with two categories. The classes were border, appearance, and shape. The categories were smooth/irregular, continuous/discontinuous, and oval/ring-shaped. The review was performed on the PCD-D50 data, since CBA was hypothesized to be most apparent in EID-D50, and image noise highest in PCD-D60. For each calcification, the morphological description was based on the features in a majority of the CT images. To optimize the visual depiction of calcification morphology, the window width/level was adjusted according to attenuation variations in the calcifications. Examples of the morphological features in the included calcifications are shown in Fig. 1.

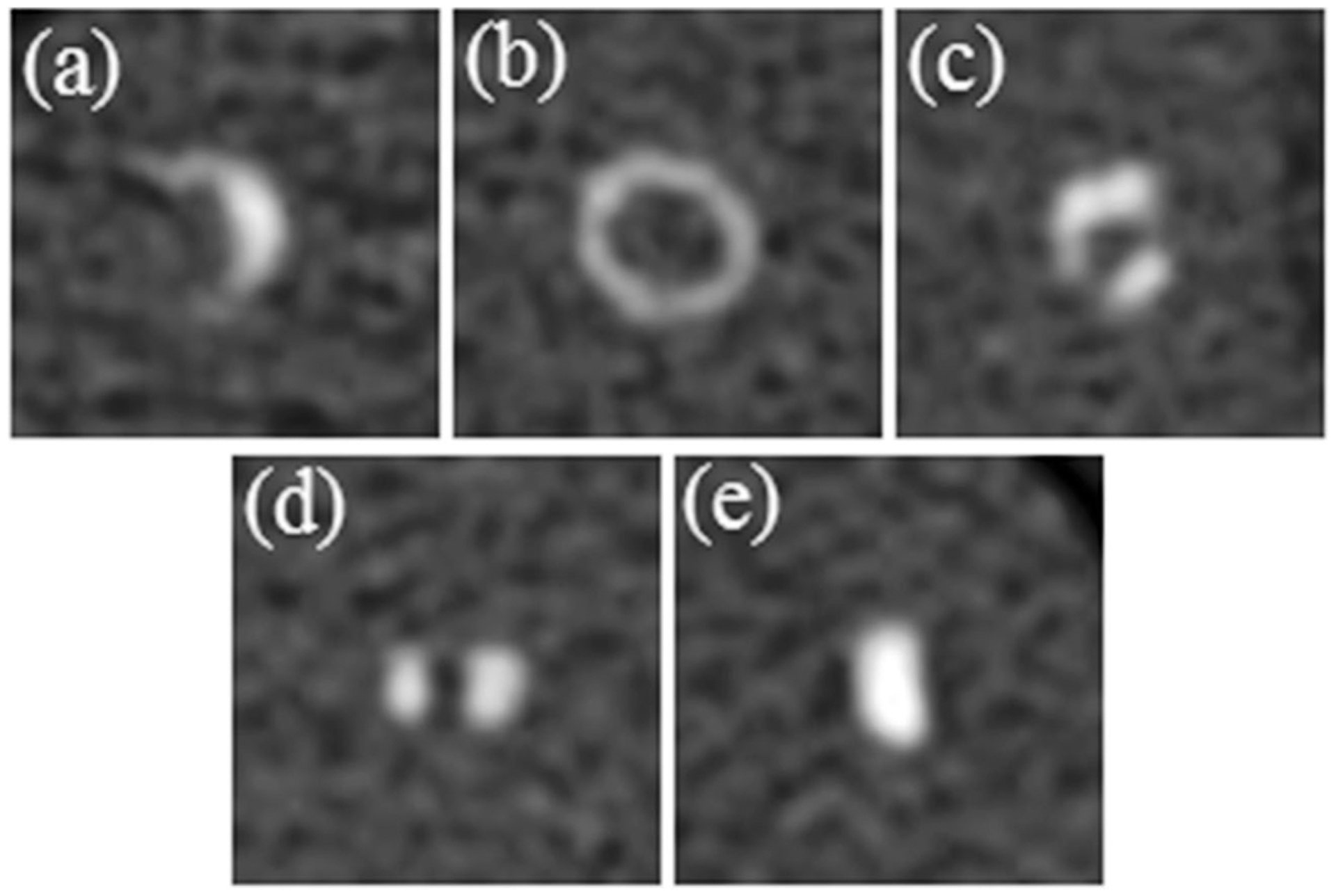

Fig.1.

Five calcification types with different morphological features, reconstructed using PCD-D50 data. Each magnified image is 50 × 50 voxels (11.7 mm × 11.7 mm). The window level/width was adjusted to clearly visualize the morphological features in each calcification. a A calcification with an irregular border. b A ring-shaped calcification. c A discontinuous calcification with irregular border. d A discontinuous calcification with a smooth border. e A continuous, oval-shaped calcification

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as median and interquartile ranges (IQR) or mean and SD. Normality was tested with Shapiro-Wilk’s test. Differences in calcified volume measurements between EID-D50, PCD-D50, PCD-D60, and micro-CT were analyzed with the Friedman test and a post hoc pairwise Wilcoxon signed rank test with the Bonferroni correction. The concordance for EID-D50, PCD-D50, and PCD-D60 in relation to micro-CT was analyzed with Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) and presented with 95% confidence interval (CI). The Bland-Altman method [34] evaluated the mean difference and 95% limits of agreement for EID-D50, PCD-D50, and PCD-D60 in relation to micro-CT. Since the data were not normally distributed, quantiles of the original data were applied for the analyses, according to the method of Harrell and Davis [35].

Differences in image noise measurement between EID-D50, PCD-D50, and PCD-D60 were analyzed with a repeated-measures ANOVA test and post hoc pairwise comparison with the Bonferroni correction. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In 12 of the 13 calcifications (92.3%), the calcified volume measurements were the largest in the EID-D50 image set. These 12 calcifications exhibited the following volumetric trend: EID-D50 > PCD-D50 > PCD-D60 > micro-CT (Figs. 2 and 3). In 1 of the 13 calcifications (7.7%), the calcified volume measurement was largest in PCD-D60, showing a gradual decrease following the order of PCD-D50, EID-D50, and micro-CT.

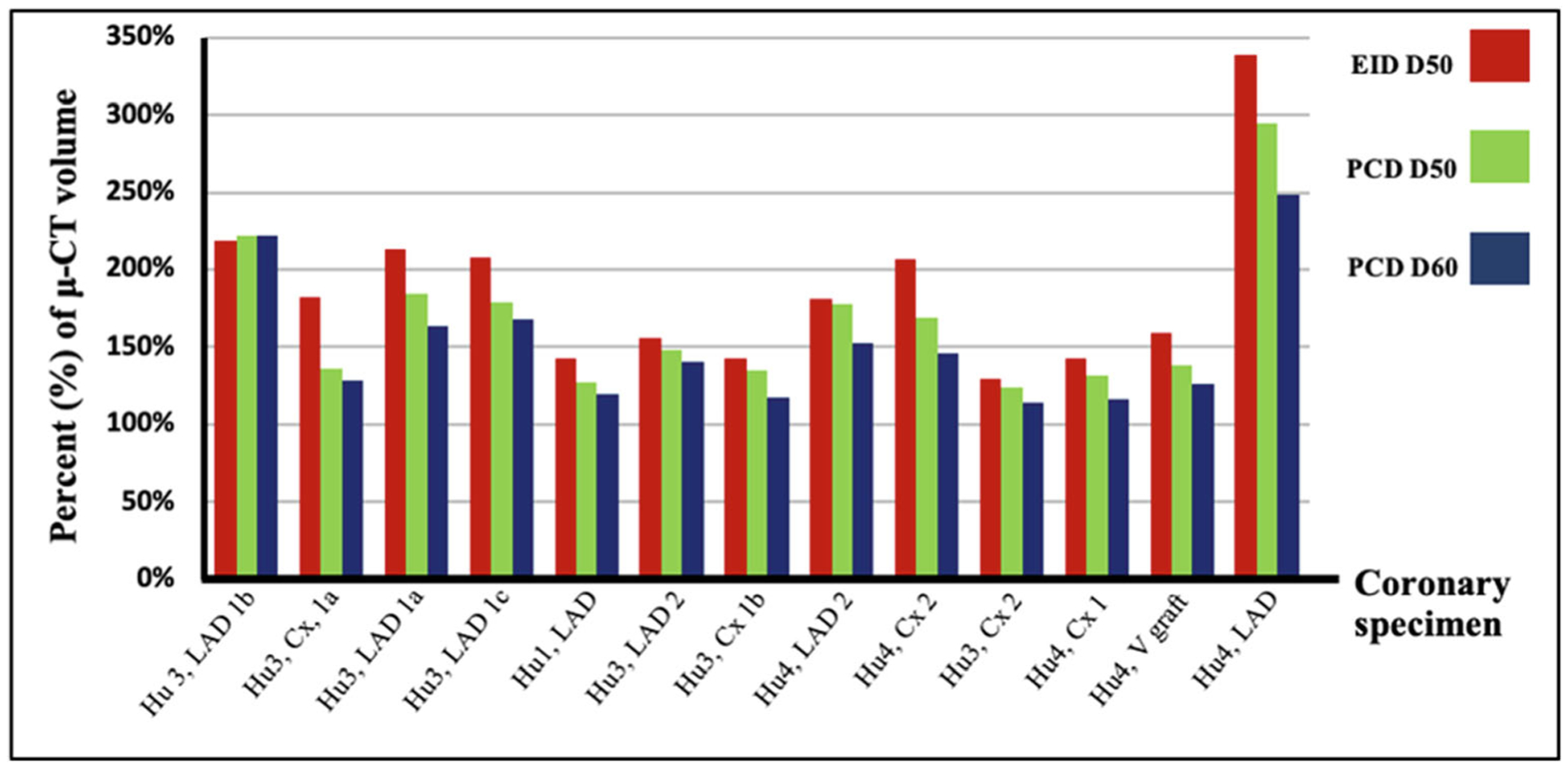

Fig. 2.

The volume of each calcification measured on EID-D50, PCD-D50, and PCD-D60 expressed as a percentage of the micro-CT volume. The volume in 12 of the 13 total calcifications followed a similar trend: EID-D50 > PCD-D50 > PCD-D60 > micro-CT

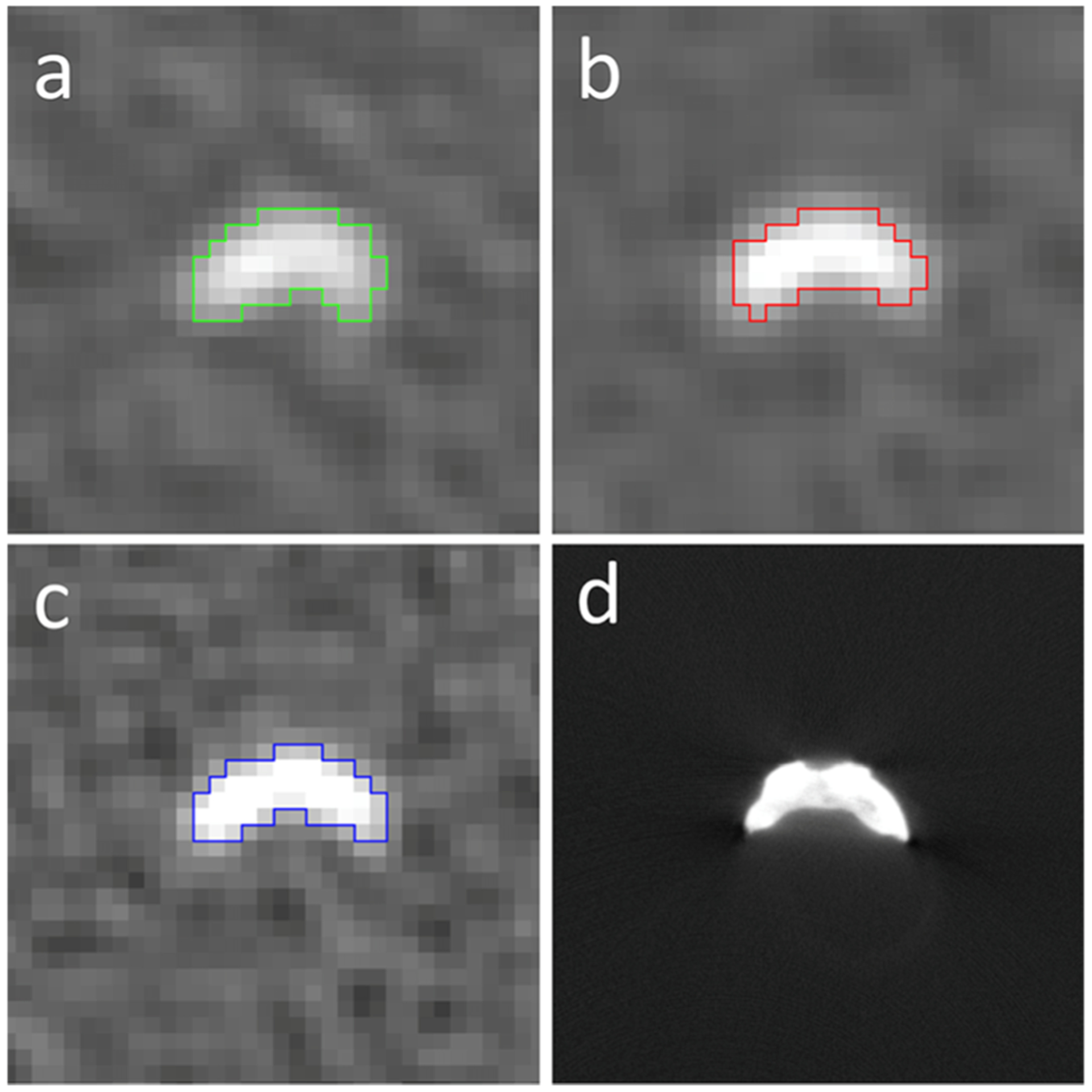

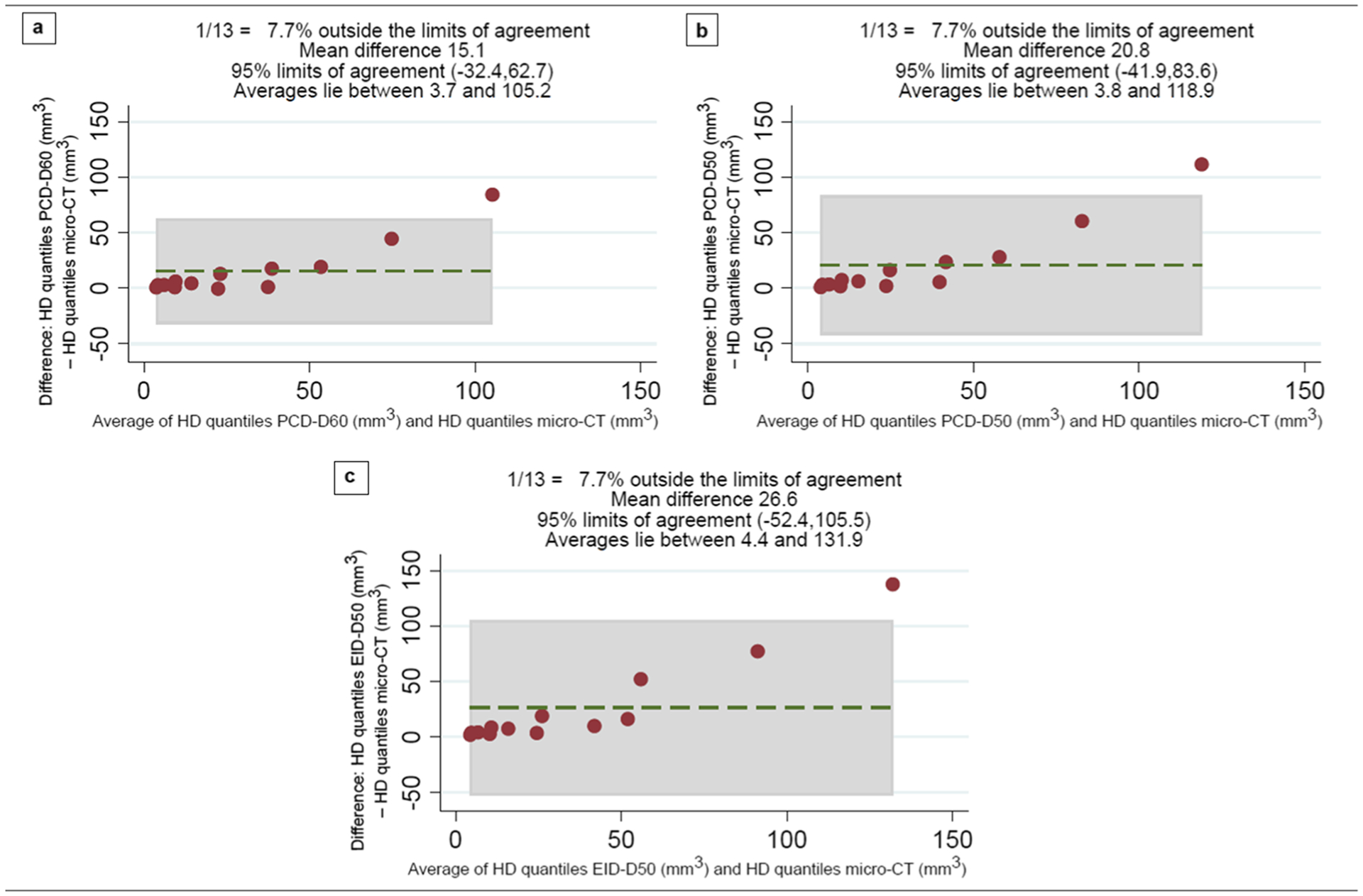

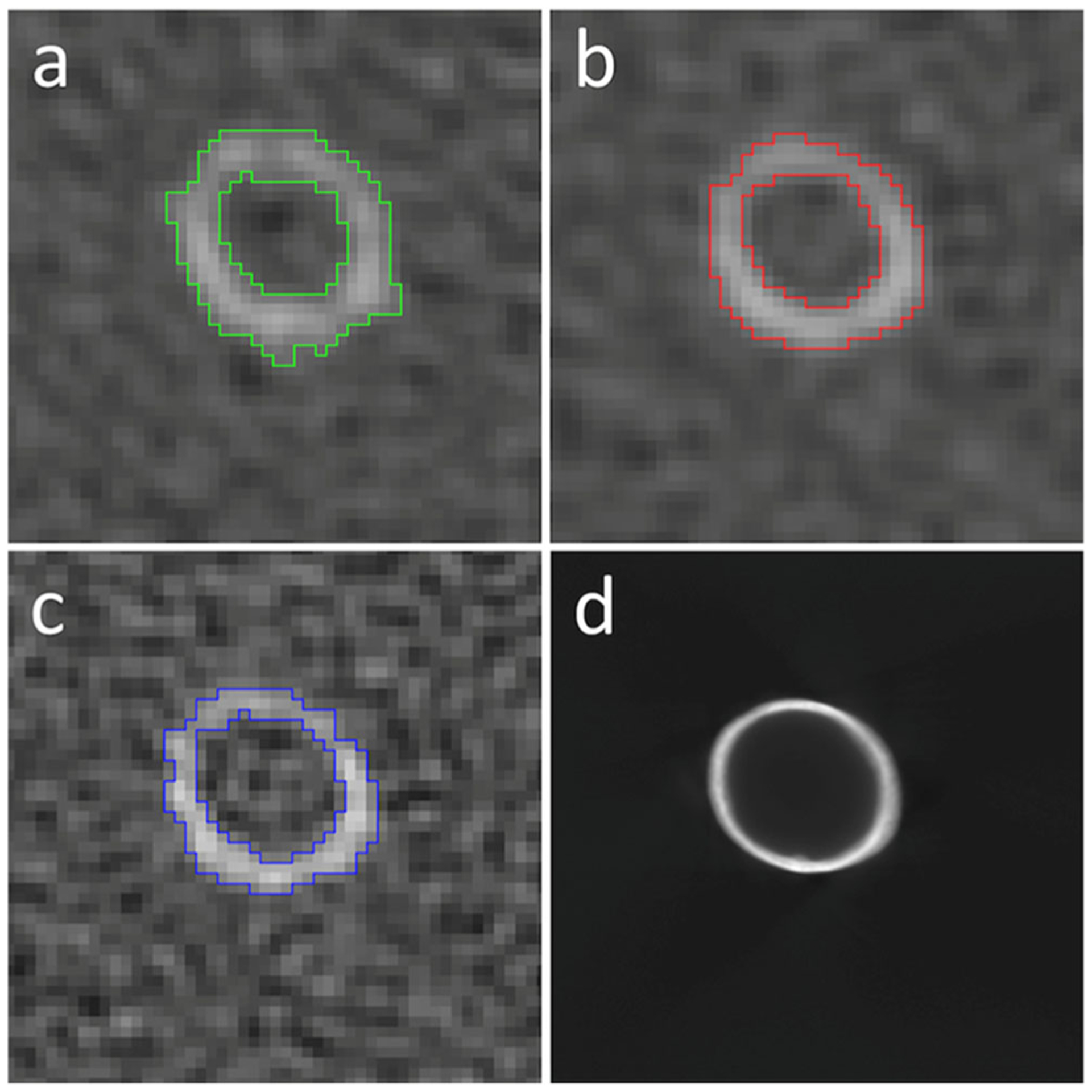

Fig. 3.

A smooth border, continuous, oval-shaped calcification with the half-maximum thresholds (HMT) overlaid (EID-CT, PCD-CT display window level/width: 2128/458 HU). a EID-D50: HMT in green, 62 voxels. b PCD-D50: HMT in red, 55 voxels. c PCD-D60: HMT in blue, 48 voxels. d Corresponding micro-CT image

The median calcified volume measurements in EID-D50, PCD-D50, PCD-D60, and micro-CT were 22.1 (IQR 10.2–64.8), 21.0 (IQR 9.0–56.5), 18.2 (IQR 8.3–49.3), and 14.6 (IQR 5.1–42.4) mm3, respectively. Summary statistics for EID-D50, PCD-D50, PCD-D60, and micro-CT volumes are shown in Fig. 4. A Friedman test and a post hoc pairwise Wilcoxon signed rank test with the Bonferroni correction showed significant differences between the calcified volume measurements comparing EID-D50 with PCD-D50, EID-D50 with PCD-D60, and PCD-D50 with PCD-D60 (p<0.05 for all pairwise comparisons). Also, there were significant differences in the calcified volume measurements comparing EID-D50 with micro-CT, PCD-D50 with micro-CT, and PCD-D60 with micro-CT (p < 0.01 for all pairwise comparisons). The CCC for EID-D50, PCD-D50, and PCD-D60 in relation to micro-CT was 0.49 (95% CI 0.30–0.67), 0.56 (95% CI 0.37–0.75), and 0.66 (95% CI 0.48–0.83), respectively. Bland-Altman plots with the Harrell and Davis method for EID-D50, PCD-D50, and PCD-D60 in relation to micro-CT showed mean difference and 95% limits of agreement 26.6 (− 52.4 to 105.5), 20.8 (− 41.9 to 83.6), and 15.1 (− 32.4 to 62.7), respectively (Fig. 5).

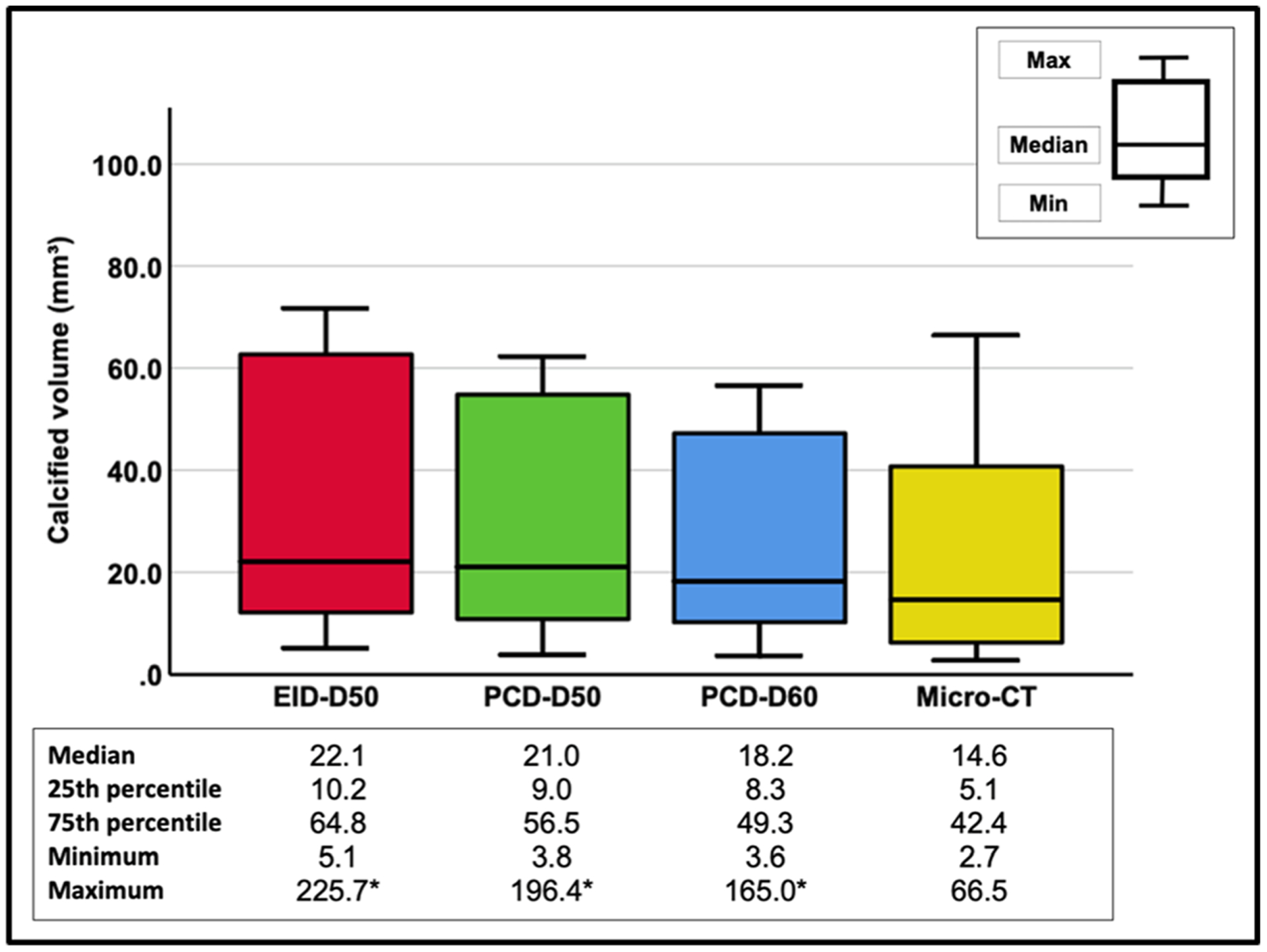

Fig. 4.

Summary statistics with boxplots showing the calcified volume measurements (mm3) for EID-D50, PCD-D50, PCD-D60, and micro-CT, respectively. Inside each box, the horizontal line indicates the median, while the bottom and top edges indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The whiskers indicate variability outside the quartiles. Below the boxplots are the corresponding volume measurements depicted (mm3). The volume of the largest calcification in EID-D50, PCD-D50, and PCD-D60 was 225.7, 196.4, and 165.0 mm3, respectively. These three outliers’ value is shown as the numerical maximum volume measurements (mm3) and indicated with an asterisk (below the boxplots) but are not depicted in the graph

Fig. 5.

Bland-Altman plots according to the Harrell and Davis method, using quantiles of the original values. The mean difference is indicated with a dotted green line and the 95 % limits of agreement are shown in gray. a PCD-D60 in relation to micro-CT: mean difference 15.1 and 95% limits of agreement − 32.4 to 62.7. b PCD-D50 in relation to micro-CT: mean difference 20.8 and 95 % limits of agreement −41.9 to 83.6. c EID-D50 in relation to micro-CT: mean difference 26.6 and 95% limits of agreement − 52.4 to 105.5. HD quantiles indicate Harrell and Davis quantiles

Table 2 shows the 13 calcified volume measurements for EID-D50, PCD-D50, PCD-D60, and micro-CT. Also, the morphological description is displayed. One calcification displayed large measurement discrepancies comparing micro-CT with EID-CT and PCD-CT and also between EID and PCD reconstructions (EID-D50, PCD-D50, PCD-D60, and micro-CT volumes of 225.7, 196.4, 165.0, and 66.5 mm3). The discrepancies can be explained as excessive PVA, due to the extensive ring-like shape, and likely a high-density calcification, contributing at both the internal and external borders (Fig. 6).

Table 2.

The EID-D50, PCD-D50, PCD-D60, and micro-CT volume measurements in mm3 for all 13 calcifications, with the number of voxels in parenthesis (the micro-CT voxels are not applicable in comparison with CT). A morphological description of the calcifications is displayed in classes and categories. Classes are border, appearance, and shape. Categories are smooth/irregular, continuous/discontinuous, and oval/ring-shaped, respectively

| Coronary calcium specimen | EID D50 mm3 (voxels) | PCD D50 mm3 (voxels) | PCD D60 mm3 (voxels) | Micro-CT mm3 (voxels) | Morphological description (border/appearance/shape) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hu 1, LAD | 12.1 (222) | 10.8 (197) | 10.2 (186) | 8.5 (n/a) | Smooth border/continuous/oval shaped |

| Hu 3, LAD 1a | 12.9 (235) | 11.1 (202) | 10.4 (189) | 6.2 (n/a) | Smooth border/continuous/oval shaped |

| Hu 3, LAD 1b | 5.9 (107) | 6.0 (109) | 6.0 (110) | 2.7 (n/a) | Irregular border/continuous/oval shaped |

| Hu 3, LAD 1c | 8.3 (152) | 7.2 (131) | 6.4 (117) | 3.9 (n/a) | Smooth border/continuous/oval shaped |

| Hu 3, LAD 2 | 22.8 (416) | 21.6 (394) | 20.6 (375) | 14.6 (n/a) | Irregular border/discontinuous/oval shaped |

| Hu 3, Cx 1a | 5.1 (92) | 3.8 (68) | 3.6 (66) | 2.8 (n/a) | Smooth border/continuous/oval shaped |

| Hu 3, Cx 1b | 22.1 (403) | 21.0 (383) | 18.2 (331) | 15.5 (n/a) | Smooth border/continuous/oval shaped |

| Hu 3, Cx2 | 52.9 (964) | 50.6 (922) | 46.4 (846) | 40.7 (n/a) | Smooth border/continuous/oval shaped |

| Hu 4, LAD 1 | 225.7 (4127) | 196.4 (3578) | 165.0 (3006) | 66.5 (n/a) | Smooth border/continuous/ring shaped |

| Hu 4, LAD 2 | 18.0 (327) | 17.6 (320) | 15.1 (275) | 9.9 (n/a) | Irregular border/discontinuous/oval shaped |

| Hu 4, Cx 1 | 62.7 (1143) | 58.1 (1059) | 51.4 (936) | 44.0 (n/a) | Smooth border/discontinuous/oval shaped |

| Hu 4, Cx 2 | 66.8 (1216) | 54.8 (998) | 47.2 (859) | 32.3 (n/a) | Irregular border/continuous/oval shaped |

| Hu 4, V graft | 71.8 (1308) | 62.3 (1135) | 56.6 (1030) | 45.0 (n/a) | Irregular border/continuous/oval shaped |

Hu, human; LAD, left anterior descending artery; Cx, circumflex artery; V graft, venous graft; EID, energy-integrating detector; PCD, photon-counting detector; n/a, not applicable

Fig. 6.

A smooth border, continuous calcification with a ring-like shape, with the half-maximum thresholds (HMT) overlaid. Compound calcium blooming artifacts present at both the inner and outer boundaries induced an incremental volume discrepancy between EID-CT, PCD-CT, and micro-CT measurements (EID-CT, PCD-CT display window level/width: 1735/466 HU). a EID-D50: HMT in green, 249 voxels. b PCD-D50: HMT in red, 197 voxels. c PCD-D60: HMT in blue, 137 voxels. d Corresponding micro-CT image

The average image noise in EID-D50, PCD-D50, and PCD-D60 was 60.4 (± 3.5), 56.0 (± 4.2), and 113.6 (± 8.5) HU, respectively. A repeated-measures ANOVA test with post hoc pairwise comparison using the Bonferroni correction showed significant differences comparing EID-D50 with PCD-D50, EID-D50 with PCD-D60, and PCD-D50 with PCD-D60 (p < 0.01 for all pairwise comparisons).

Discussion

In this study, ex vivo coronary calcifications exhibited more accurate volume measurements in PCD-CT than in EID-CT. This could be attributed to the increased spatial resolution with smaller detector pixels employed in PCD-CT that minimizes the PVA and reduces CBA.

The volume measurements in 12/13 calcifications followed a similar trend: EID-D50 > PCD-D50 > PCD-D60 > micro-CT. Correspondingly, PCD-D60 had the strongest volume measurement concordance in relation to micro-CT, followed by PCD-D50 and EID-D50. In 1/13 calcifications, the largest volume measurements were found in PCD-CT, induced by local noise variations, but only resulted in 0.1 mm3 EID-CT and PCD-CT differences. Notably, this calcification was relatively small, making the measurements more vulnerable to noise. A ring-shaped calcification displayed large volume measurement discrepancies, particularly comparing micro-CT with EID-CT and PCD-CT, reflecting shape-dependent variations in the magnitude and direction of CBA (Fig. 6). This may have clinical implications, since CAC surrounding > 50% of lumen circumference is shown to reduce CCTA specificity [36]. There were further morphological variations among the 13 calcifications, but no other correlations were found between the morphological features and the volume.

Most calcification volume measurements (92.3%) were less in PCD-CT than in EID-CT, while all micro-CT volume measurements were less than PCD-CT. Thus, even though PCD-CT has less CBA than EID-CT, it is still present. However, the PCD-CT utilization of high energy data has the potential to further reduce CBA [37, 38]. This study used the sharp mode, which acquired high energy threshold data, but the corresponding images are also associated with more noise, which requires noise reduction techniques; this was considered beyond the scope of this study.

The image noise was less in PCD-D50 than in EID-D50, which was expected [24], and likely clinically beneficial alongside reduced CBA. However, due to the use of thin (1 mm) slices with conventional WFBP, all EID-CT and PCD-CT images exhibited relatively high noise levels. As a tradeoff to improved resolution, image noise was the highest in PCD-D60. The noise could be reduced by using an iterative reconstruction algorithm or denoising techniques [39].

An adaptive HMT technique was used, while clinical CAC scoring typically uses a fixed threshold of 130 HU. Previous works have shown CT number differences between EID-CT and PCD-CT for the same attenuating medium, since the photon energy-weighting scheme in PCD-CT is uniform whereas EIDs have non-uniform weighting [38, 40]. The HMT methodology takes into account the HU differences between modalities (EID-CT, PCD-CT, micro-CT) and could be applied on each image, in each calcification, and is well-suited across different kernels and reconstruction settings.

While the PCD-CT performance on CSCT previously has been reported on [41], this study has another approach, namely investigating the PCD-CT benefits of ultra-high resolution for CAC volume quantification. The results reflect that smaller PCD-CT detectors cause less PVA, which reduces CBA. By extension, PCD-CT could have the potential to improve the diagnostic accuracy of CAC evaluation in CT imaging. Recently introduced EID-CT system offers small detector pixel size (0.25 mm) for UHR imaging [42]. In comparison to this system, PCD-CT does not use inter-pixel reflective septa which results in better geometric dose efficiency for UHR imaging. PCD provides additional benefits such as simultaneous multi-energy imaging [43, 44], elimination of electronic noise through energy thresholding [45], and improved CNR due to uniform photon-weighting [38].

This study has several limitations. First, it is conducted using static cadaveric specimens, but in vivo studies are warranted to further demonstrate the PCD-CT applicability on coronary calcification imaging. An in vivo coronary PCD-CT imaging study will, despite adequate cardiac gating and temporal resolution, probably have some degree of motion artifacts that could affect calcification quantification. Second, to approach the potential PCD-CT benefits of reducing CBA in CCTA, additional studies are needed with iodine in the vessel lumen. Multi-energy processing (such as material decomposition) needs to be evaluated in the context of contrast-enhanced CCTA. Third, this study had a relatively few numbers of inclusions. However, the results should primarily guide further research involving PCD-CT for coronary calcium imaging. Similar to any image segmentation techniques, image noise could influence the performance of the proposed technique and requires further investigation. For instance, we did not utilize iterative reconstruction which could introduce contrast-dependent non-linearity and variable performance between PCD-CT and EID-CT; our primary focus was to assess the fundamental performance of the two modalities for calcium volume quantification at the current clinical dose level without any additional processing; therefore, we reconstructed all images using standard filtered back projection. Even though the calcified volume measurements showed statistically significant differences, in vivo human studies in a larger population are needed to validate the results.

Conclusion

The quantification of coronary calcifications in human cadaver specimens was more accurate using the PCD-CT than the EID-CT, and the sharp kernel on PCD-CT further improved the accuracy. The results reflect that smaller detector pixels such as the ones used in PCD-CT improves spatial resolution and reduces PVA, consequently minimizing the blooming-induced discrepancies. The PCD-CT images also exhibited lower noise than the EID-CT images at matched radiation dose and kernel.

Key Points.

High spatial resolution offered by PCD-CT reduces partial volume averaging and consequently leads to better morphological depiction of coronary calcifications.

Improved quantitative accuracy for coronary calcification volumes could be achieved using high-resolution PCD-CT compared to conventional EID-CT.

PCD-CT images exhibit lower image noise than conventional EID-CT at matched radiation dose and reconstruction kernel.

Acknowledgements

The authors would also like to thank Mats Fredriksson, Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Linköping University, who provided statistical advice. The authors thank Kristina Nunez, Mayo Clinic, for her assistance in manuscript preparation.

Funding

The research reported in this work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under awards R01 EB016966 and C06 RR018898. This work was supported in part by the Mayo Clinic X-ray Imaging Research Core. This research project was also supported by the Mayo Clinic-Karolinska Institutet Collaboration platform and by ALF grants, Region Östergötland.

Conflict of interest

Research support for this work was provided, in part, to the Mayo Clinic from Siemens Healthcare GmbH. The research CT system used in this work was provided by Siemens Healthcare GmbH; it is not commercially available.

Abbreviations

- CAC

Coronary artery calcifications

- CAD

Coronary artery disease

- CBA

Calcium blooming artifacts

- CCC

Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient

- CCTA

Coronary computed tomography angiography

- CI

Confidence interval

- CNR

Contrast-to-noise ratio

- CSCT

Calcium scoring computed tomography

- CT

Computed tomography

- CTDIvol

Volume CT dose index

- CV

Cardiovascular

- EID

Energy-integrating detector

- FOV

Field of view

- HMT

Half-maximum threshold

- HU

Hounsfield Units

- IQR

Interquartile ranges

- MMA

Methyl methacrylate

- NCCT

Non-contrast, non-gated chest CT

- PCD

Photon-counting detector

- PVA

Partial volume averaging

- ROI

Region of interest

- SD

Standard deviation

- UHR

Ultra-high resolution

- WFBP

Weighted filtered back projection

Footnotes

- prospective

- observational

- performed at one institution

References

- 1.Global Health Estimates (2016) Deaths by cause, age, sex, by country and by region, 2000–2016. World Health Organization, Geneva [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sangiorgi G, Rumberger JA, Severson A et al. (1998) Arterial calcification and not lumen stenosis is highly correlated with atherosclerotic plaque burden in humans: a histologic study of 723 coronary artery segments using nondecalcifying methodology. J Am Coll Cardiol 31:126–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rumberger JA, Simons DB, Fitzpatrick LA, Sheedy PF, Schwartz RS (1995) Coronary artery calcium area by electron-beam computed tomography and coronary atherosclerotic plaque area. A histopathologic correlative study. Circulation 92:2157–2162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Detrano R, Guerci AD, Carr JJ et al. (2008) Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N Engl J Med 358:1336–1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenland P, Blaha MJ, Budoff MJ, Erbel R, Watson KE (2018) Coronary calcium score and cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol 72:434–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y, Osborne MT, Tung B, Li M, Li Y (2018) Imaging cardiovascular calcification. J Am Heart Assoc 7(13):e008564. 10.1161/JAHA.118.008564PMID:29954746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G et al. (2014) 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 63:2935–2959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A et al. (2020) 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 41:407–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J et al. (2012) 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation 126:e354–e471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hecht HS, Cronin P, Blaha MJ et al. (2017) 2016 SCCT/STR guidelines for coronary artery calcium scoring of noncontrast noncardiac chest CT scans: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography and Society of Thoracic Radiology. J Thorac Imaging 32:W54–w66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M Jr, Detrano R (1990) Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 15:827–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mowatt G, Cummins E, Waugh N et al. (2008) Systematic review of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of 64-slice or higher computed tomography angiography as an alternative to invasive coronary angiography in the investigation of coronary artery disease. Health Technol Assess 12:iii–iv ix–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kroft LJ, de Roos A, Geleijns J (2007) Artifacts in ECG-synchronized MDCT coronary angiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 189:582–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalisz K, Buethe J, Saboo SS, Abbara S, Halliburton S, Rajiah P (2016) Artifacts at cardiac CT: physics and solutions. Radiographics 36:2064–2083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blaha MJ, Mortensen MB, Kianoush S, Tota-Maharaj R, Cainzos-Achirica M (2017) Coronary artery calcium scoring: is it time for a change in methodology? JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 10:923–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Bijl N, de Bruin PW, Geleijns J et al. (2010) Assessment of coronary artery calcium by using volumetric 320-row multidetector computed tomography: comparison of 0.5 mm with 3.0 mm slice reconstructions. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 26:473–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dehmeshki J, Ye X, Amin H, Abaei M, Lin X, Qanadli SD (2007) Volumetric quantification of atherosclerotic plaque in CT considering partial volume effect. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 26:273–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muhlenbruch G, Klotz E, Wildberger JE et al. (2007) The accuracy of 1- and 3-mm slices in coronary calcium scoring using multi-slice CT in vitro and in vivo. Eur Radiol 17:321–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu B, Budoff MJ, Zhuang N et al. (2002) Causes of interscan variability of coronary artery calcium measurements at electron-beam CT. Acad Radiol 9:654–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sprem J, de Vos BD, Lessmann N et al. (2018) Coronary calcium scoring with partial volume correction in anthropomorphic thorax phantom and screening chest CT images. PLoS One 13:e0209318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Budoff MJ, Dowe D, Jollis JG et al. (2008) Diagnostic performance of 64-multidetector row coronary computed tomographic angiography for evaluation of coronary artery stenosis in individuals without known coronary artery disease: results from the prospective multicenter ACCURACY (Assessment by Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography of Individuals Undergoing Invasive Coronary Angiography) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 52:1724–1732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdulla J, Pedersen KS, Budoff M, Kofoed KF (2012) Influence of coronary calcification on the diagnostic accuracy of 64-slice computed tomography coronary angiography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 28:943–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leng S, Yu Z, Halaweish A et al. (2016) Dose-efficient ultrahigh-resolution scan mode using a photon counting detector computed tomography system. J Med Imaging (Bellingham) 3:043504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leng S, Rajendran K, Gong H et al. (2018) 150-mum spatial resolution using photon-counting detector computed tomography technology: technical performance and first patient images. Invest Radiol 53:655–662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou W, Lane JI, Carlson ML et al. (2018) Comparison of a photon-counting-detector CT with an energy-integrating-detector CT for temporal bone imaging: a cadaveric study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 39:1733–1738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mannil M, Hickethier T, von Spiczak J et al. (2018) Photon-counting CT: high-resolution imaging of coronary stents. Invest Radiol 53:143–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kappler S, Glasser F, Janssen S, Kraft E, Reinwand M (2010) A research prototype system for quantum-counting clinical CT. SPIE, Proc. SPIE 7622, Medical Imaging 2010: Physics of Medical Imaging, 76221Z 10.1117/12.844238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kappler S, Henning A, Kreisler B, Schoeck F, Stierstorfer K, Flohr T (2014) Photon counting CT at elevated X-ray tube currents: contrast stability, image noise and multi-energy performance. SPIE. Proc. SPIE 9033, Medical Imaging 2014: Physics of Medical Imaging, 90331C 10.1117/12.2043511 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu Z, Leng S, Jorgensen SM et al. (2016) Evaluation of conventional imaging performance in a research whole-body CT system with a photon-counting detector array. Phys Med Biol 61:1572–1595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stierstorfer K, Rauscher A, Boese J, Bruder H, Schaller S, Flohr T (2004) Weighted FBP–a simple approximate 3D FBP algorithm for multislice spiral CT with good dose usage for arbitrary pitch. Phys Med Biol 49:2209–2218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pedigo SL, Guth CM, Hocking KM et al. (2017) Calcification of human saphenous vein associated with endothelial dysfunction: a pilot histopathophysiological and demographical study. Front Surg 4:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rajendran K, Leng S, Jorgensen SM et al. (2017) Measuring arterial wall perfusion using photon-counting computed tomography (CT): improving CT number accuracy of artery wall using image deconvolution. J Med Imaging (Bellingham) 4:044006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rueden CT, Schindelin J, Hiner MC et al. (2017) ImageJ2: ImageJ for the next generation of scientific image data. BMC Bioinformatics 18:529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bland JM, Altman DG (1986) Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1:307–310 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrell FE, Davis CE (1982) A new distribution-free quantile estimator. Biometrika 69:635–640 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qi L, Tang LJ, Xu Y et al. (2016) The diagnostic performance of coronary CT angiography for the assessment of coronary stenosis in calcified plaque. PLoS One 11:e0154852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Hedent S, Grosse Hokamp N, Kessner R, Gilkeson R, Ros PR, Gupta A (2018) Effect of virtual monoenergetic images from spectral detector computed tomography on coronary calcium blooming. J Comput Assist Tomogr 42:912–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gutjahr R, Halaweish AF, Yu Z et al. (2016) Human imaging with photon counting-based computed tomography at clinical dose levels: contrast-to-noise ratio and cadaver studies. Invest Radiol 51:421–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Z, Leng S, Yu L, Manduca A, McCollough CH (2017) An effective noise reduction method for multi-energy CT images that exploit spatio-spectral features. Med Phys 44:1610–1623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Juntunen MAK, Inkinen SI, Ketola JH et al. (2020) Framework for photon counting quantitative material decomposition. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 39:350–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Symons R, Sandfort V, Mallek M, Ulzheimer S, Pourmorteza A (2019) Coronary artery calcium scoring with photon-counting CT: first in vivo human experience. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 35:733–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kakinuma R, Moriyama N, Muramatsu Y et al. (2015) Ultra-high-resolution computed tomography of the lung: image quality of a prototype scanner. PLoS One 10:e0137165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Willemink MJ, Persson M, Pourmorteza A, Pelc NJ, Fleischmann D (2018) Photon-counting CT: Technical Principles and Clinical Prospects. Radiology 289:293–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ren L, Rajendran K, McCollough CH, Yu L (2019) Radiation dose efficiency of multi-energy photon-counting-detector CT for dual-contrast imaging. Phys Med Biol 64:245003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu Z, Leng S, Kappler S et al. (2016) Noise performance of low-dose CT: comparison between an energy integrating detector and a photon counting detector using a whole-body research photon counting CT scanner. J Med Imaging 3:043503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]