Abstract

Sepsis remains to be a significant health care problem associated with high morbidities and mortalities. Recognizing its heterogeneity, it is critical to understand our host immunological responses to develop appropriate therapeutic approaches according to the type of sepsis. Because pattern recognition receptors are largely responsible for the recognition of microbes, we reviewed their role in immunological responses in the setting of bacterial, fungal and viral sepsis. We also considered their therapeutic potentials in sepsis.

Keywords: sepsis, bacteria, fungus, virus, pattern recognition receptors

Background

Sepsis is a very complex, heterogeneous and pathological syndrome resulting from microbial infection. Sepsis remains to be associated with high morbidities and mortalities but there are no specific therapies available other than supportive management 1. Supportive management largely consists of antibiotics therapy, fluid resuscitation and respiratory support as needed 2. As sepsis is defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to any infection in the third International Consensus Definitions Task Force (Sepsis-3) 3, responsible pathogens range widely from bacteria, virus to fugal species. Causative microbes are identified in only 60-70% of cases 4 and bacteria account for most of the identified organisms, followed by fungus. The reported percentage of viral sepsis is only in a range of 1% 5,6. Viral panel is not necessarily included in a routine sepsis workup algorithm, however, so that viral sepsis may be under-represented 7 The heterogeneity of sepsis has been well recognized and could at large explain the fact that the clinical trials of various anti-cytokine antibodies universally failed. In addition to current supportive treatment, a new therapy is urgently warranted.

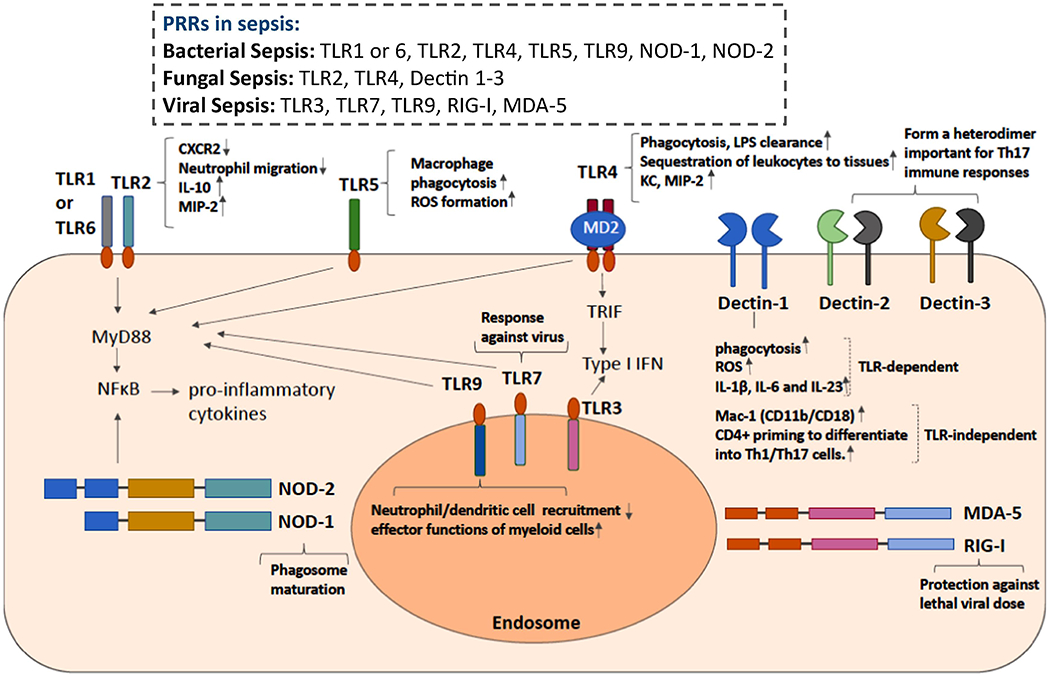

Our immune system is mounted with a number of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) to respond to a wide variety of microbes in the environment. PRRs include Toll-like receptors (TLRs), nucleotide binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs), retinoic acid-inducible gene (RIG)-I-like receptors (RLRs), C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) and DNA-sensing molecules 8. Understanding how our host immunity responds to microbial components by using these PRRs is critical to decipher sepsis pathophysiology. With PRRs as new targets for sepsis treatment, we reviewed host immunological responses to bacterial, fungal and viral sepsis for their similarities and differences in respect to PRR responses.

Bacterial sepsis

Bacterial sepsis is the most common type of sepsis. Bacterial species are largely divided into Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. According to the Extended Prevalence of Infection in Intensive Care (EPIC) II study, 62.2% of patients had positive blood cultures harboring Gram-negative bacteria and 46.8% were infected with Gram-positive bacteria 9,10. A group of patients experienced polymicrobial sepsis with both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. While Escherichia coli (E. coli) can be found in approximately 1 in 6 culture-positive septic patients, and other predominant Gram-negative bacteria species in sepsis include Pseudomonas, Klebsiella and Enterobacter species. Gram-positive bacterial species such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) have made up an increasing percentage of sepsis with the advent of excessive antibiotic treatment.

Immunological responses in bacterial sepsis

The components of bacterial cell walls are main targets that host immune cells use as to recognize bacteria. Among PRRs, TLR and NLR members play a pivotal role in sensing bacteria. The cell walls of Gram-positive bacteria consist mainly of peptidoglycan, glycolipid lipoteichoic acid, and lipoproteins. Peptidoglycan is a unique component of the cell wall of virtually all the bacteria and recognized by TLR2, and NOD-containing protein-1 and -2 (NOD-1, NOD-2). Lipoteichoic acid and lipoproteins are recognized by TLR2 8. In addition to these cell wall components, TLR9 recognizes unmethylated CpG motifs present in bacterial DNA 11. The cell walls of Gram-negative bacteria contain peptidoglycan, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), phospholipids and proteins. Lipid A portion of LPS is characteristic of Gram-negative bacteria and consists of a mono- or biphosphorylated disaccharide backbone acetylated with fatty acids. The level of both phosphorylation and acylation determines the immunostimulatory potency of lipid A/LPS. LPS is recognized by myeloid differentiation factor 2 (MD-2)/TLR4 complex. Flagellin is a major component of flagella, mainly found in Gram negative bacteria. Flagellin is recognized by TLR5.

A number of PRRs used for bacterial recognition are distributed on different cell types and activate overlapping but redundant signaling pathways. TLRs are expressed on the cellular membrane or the endocytic vesicles, with characteristic horseshoe conformation consisting of leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) that serve as ligand binding sites. TLR2 is expressed on myeloid cells, a subset of lymphoid cells, epithelial cells and endothelial cells 12,13. TLR4 is also expressed on myeloid cells, a subset of lymphoid cells and endothelial cells 14. TLR5 is expressed on myeloid cells and epithelial cells 15,16. TLR9 is expressed on myeloid cells and B cells 17. TLR2, TLR4, TLR5 and TLR9 activate MyD88 pathway, thereby producing nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) mediated proinflammatory cytokines (Figure 1). TLR4 also activates TRIF pathway, which induces Type I interferon. NOD-1 and NOD-2 are among NLR family and structurally related cytosolic proteins with LRR domains that are similar to those found in TLRs 18. NOD-1 and NOD-2 are expressed by epithelial cells and antigen-presenting cells 19 . NOD-1 senses a peptidoglycan-derived peptide D-gamma-Glu-mDAP (iEDAP) from all Gram-negative bacteria and a subset of Gram-positive bacteria. NOD-2 senses muramyldipeptide (MDP), a highly conserved peptidoglycan motif present in almost all bacteria. The binding of ligands to NOD-1 and NOD-2 induces their oligomerization and subsequent activation of NFkB and other effector pathways 20.

Figure 1.

Pattern recognition receptors involved in bacterial, viral and fungal sepsis

Excessive inflammation and immunosuppression are a characteristic, immunological progression pattern in sepsis 21. Overall, PRRs interact with a number of bacterial factors and contribute to the immunological responses. However, we need to understand immunological response profiles driven by an individual PRR role to consider the development of PRR targeted therapeutic approaches. The experimental polymicrobial abdominal sepsis model induced by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) surgery is the most commonly used preclinical model to study bacterial sepsis pathophysiology because it recapitulates human sepsis of warm and cold shock phases 22. One of the advantages in this model is that the severity of CLP sepsis can be easily adjusted by the length of ligated cecum and the number and size of puncture hole in the cecum. However, it is important to note that CLP sepsis with different severity may represent different pathophysiology 22. Thus, the severity of CLP sepsis needs to be paid attention.

TLR2 forms a heterodimer either with TLR1 or TLR6 to manifest its function. TLR2 KO mice showed a better survival in CLP sepsis, associated with the attenuation of CXCR2 downregulation and adequate neutrophil migration to the peritoneal cavity compared to WT mice 23. The downregulation of CXCR2, a neutrophil chemoattractant receptor for CXCL2 presumably results from TLR2 stimulation. The downregulation of CXCR2 on neutrophils at an environment rich with TLR2 ligands will minimize their migration to other locations. High levels of TLR2 ligands in circulating blood during sepsis, if exists, however, may hinder neutrophil recruitment to the infected tissues/ organs. A chimeric mouse experiment using WT and TLR2 KO mice demonstrated that altered neutrophil functions in TLR2 KO mice were derived from TLR2 KO non-hematopoietic cells 24. However, the mechanism of how the activation of TLR2 expressing non-hematopoietic cells leads to CXCR2 downregulation on neutrophils remains to be clarified. TLR2 also affects cardiac function during sepsis as TLR2 KO mice showed a better ventricular function in CLP sepsis 25. Non-hematopoietic cells also affected TLR2-mediated cardiac dysfunction during sepsis as they did for neutrophils 24.

TLR4 has been a main target of investigation in Gram-negative sepsis 26,27 The importance of TLR4 in infection is well demonstrated in patients with TLR4 Asp-299-Gly mutation, which depresses TLR4 signaling and is associated with an increased susceptibility to Gram-negative infection 28. Although primary Gram-negative bacterial infection certainly uses TLR4-mediated immunological responses, the release of LPS from gut microbiota as a result of intestinal hypoperfusion caused by Gram-positive bacterial sepsis and fungal sepsis is also indicated, suggesting that TLR4 signals are involved in a wide variety of microbial sepsis 29,30. Like TLR2, TLR4 is expressed on immune cells as well as non-immune cells. In myeloid cells, TLR4 is required for phagocytosis and bacterial clearance along with cytokine production 31. TLR4 in hepatocytes is in charge of LPS clearance. TLR4 in endothelial cells contributes to the sequestration of leukocytes to the tissues 32. Consistent with these TLR4 roles, TLR4 KO mice showed a worse survival in less severe CLP due to poor bacterial clearance 31. However, TLR4 KO mice showed a better outcome in severe CLP sepsis presumably due to a significantly less production of proinflammatory cytokines 33.

Flagellin administration was effective to reduce CLP sepsis mortality by promoting macrophage phagocytosis and reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation via its interaction with TLR5 34. In fact, neutralizing TLR5 antibody administration significantly attenuated beneficial effect of flagellin administration on CLP sepsis outcome. However, higher dose of flagellin was associated with significant proinflammatory responses and organ injury instead 35.

TLR9 KO showed a better survival with a greater number of peritoneal dendritic cells (DCs) and neutrophils along with less proinflammatory cytokine levels than WT mice 36. TLR9 KO DCs increased neutrophil recruitment presumably by producing neutrophil chemoattractants, which led to survival benefit. Does this mean that TLR9 is not necessary? In pneumococcal infections, TLR9 KO mice were much more susceptible to the infection and showed a worse survival than WT, TLR1 KO, TLR2 KO, TLR4 KO and TLR6 KO mice 37. This was due to impaired uptake of Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae) by TLR9 KO macrophages. Thus, TLR9 is also associated with effector functions of myeloid cells aside from proinflammatory cytokine production, similar to other TLRs.

Overall TLR studies using CLP sepsis indicated that the elimination of the TLR stimulation would inhibit the hyper-inflammatory systemic responses that could lead into death in severe sepsis, thereby posing a survival benefit. However, in less severe sepsis, the presence of TLR signaling has been shown protective 38. TLR2, TLR4, TLR5 and TLR9 share MyD88 signaling pathway. A study by Feng et al. showed that MyD88 KO mice demonstrated a significantly better survival along with lower proinflammatory cytokine levels and improved cardiac function following CLP surgery 38. MyD88 KO mice also showed less recruited neutrophils to the peritoneal cavity with slightly higher mean bacterial loads (not statistically significant) compared to WT mice, suggesting that their outcome advantage was likely derived from the less profound proinflammatory cytokine profiles. In contrast, a study by Sonego et al. using less severe CLP sepsis showed that MyD88 KO mice had worse survival with less neutrophil recruitment to the peritoneal cavity and more bacterial loads than WT mice 39, which is in line with the aforementioned discussion about the importance of maintaining effector functions in sepsis. The study of S. pneumoniae by Albiger et al. also demonstrated an impaired uptake of bacteria by MyD88 KO macrophages 37, demonstrating the involvement of MyD88 in effector functions other than proinflammatory cytokine production.

TLR4 also activates TRIF pathway. In contrast to MyD88 KO mice, TRIF KO mice did not show any difference in the CLP outcome 38. No significant difference in proinflammatory cytokine levels and neutrophil phagocytic activity between WT and TRIF KO mice was observed as well. The absence of NOD-1 or NOD-2 did not affect the CLP sepsis outcome 39. This raises a question whether TLR and NOD signaling are both critical for innate immunity against bacterial infection and what the rank order is regarding the importance of TLRs and NLRs. It was generally presumed that the membrane bound TLRs survey the extracellular bacteria, while the cytosolic NOD-1 and NOD-2 detect the intracellular bacteria 40. However, it was shown that S. aureus, for example, could be detected by NOD-2 41. Zhou et al. also showed that TLR and NOD signaling are both required to induce a strong inflammatory response and phagosome maturation via crosstalk between them 20, suggesting that both are required. The rank order of TLR an NOD signaling use in sepsis caused by different bacteria species remains to be determined in the future.

Therapeutic consideration

A large number of antibiotics have been developed so far to eradicate bacteria. There is no doubt that early antimicrobial therapy is critical. However, there is no direct therapy against organ injury in sepsis. Attenuating organ injury while maintaining the ability to kill bacteria by host immunity as well as anti-microbial drugs would be ideal.

Among major PRRs in bacterial sepsis, TLR4 attracted a significant attention as a potential target. LPS signal is initiated by its binding to MD-2 followed by the binding of LPS-MD-2 complex to TLR4. Eritoran (E5564) is a synthetic analog of lipid A and inhibits lipid A binding to MD-2, thereby terminating TLR4-mediated signaling (Table 1). In Phase 2 trial, 300 adult patients with severe sepsis were either given placebo or intravenous Eritoran every 12 hours for 6 days (either 45 mg total or 105 mg total) initiated within 12 hours from the first onset of organ injury. The 28-day mortality rate of Eroitan-105 mg group, Eroitan-45 mg group and placebo was 26.6%, 32.0% and 33.3%, respectively. Subjects at highest risk of mortality by APACHE II score showed that Eritoran-105 mg group had mortality rate of 33.3%, while placebo had 56.3% 42.

Table 1.

Pattern recognition receptors involved in sepsis, their functions, and known agonists and antagonists

| PRRs | Functions | Agonist/antagonist |

|---|---|---|

| TLR2 | Activates MyD88 pathway, thereby producing nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) mediated proinflammatory cytokines. Downregulates CXCR2, hindering neutrophil migration to other locations including to the infected tisues/organs during bacterial sepsis. Increases the levels of IL-10, CD4+CD25+ Treg population and MIP-2 resulting to neutrophil recruitment in fungal sepsis. TLR2 is also involved in HSV genomic recognition in viral sepsis | CBLB612 (TLR2 agonist/drug) SV-283 (NY-ESO-1) (TLR2 agonist/adjuvant) IS A-201 (TLR2/1 agonist/adjuvant) OPN-305-110 (TLR2 antagonist/drug) OPN-305 (TLR2 antagonist/drug) |

| TLR3 | Detects extracellular viral RNA that enter the cell from the endocytic pathway. Upon dsRNA recognition, TLR3 induces IFN-β and proinflammatory cytokine production from host cells | Poly(I:C) (TLR3 agonist) Poly(I:C12U) or Ampligen® (TLR3 agonist) Poly-ICLC or Hiltonol (TLR3 agonist) polyA:U (TLR3 agonist) Riboxxol (also known as RGIC®50) (TLR3 Agonist) ARNAX (TLR3 Agonist) |

| TLR4 | Activates MyD88 pathway, thereby producing nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) mediated proinflammatory cytokines. TLR4 also activates TRIF pathway, which induces Type I interferon. TLR4 is required for phagocytosis and bacterial clearance along with cytokine production in bacterial sepsis. TLR4 in hepatocytes is in charge of LPS clearance. TLR4 in endothelial cells contributes to the sequestration of leukocytes to the tissues. Is associated with increased chemokine (KC, MIP-2) expression and neutrophil recruitment in fungal sepsis. | Monophosphoryl lipid A (TLR4 agonist) Eritoran tetrasodium (E5564) (TLR4 antagonist) TAK-242 (Res atorvid) (TLR4 antagonist) CRX-526 (TLR4 antagonist) |

| TLR5 | Activates MyD88 pathway, thereby producing nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) mediated proinflammatory cytokines. Promotes macrophage phagocytosis and reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation Ada its interaction with flagelin in CLP sepsis. | Entolimod (CBLB502) (TLR5 agonist) |

| TLR7 | TLR7 detects extracellular viral RNA (ssRNA) on pDCs and mediates protection against lethal viral dose. | Imiquimod or Aldara™ (TLR7 agonist) PF-04878691 or 852A (TLR7 agonist) ANA975 (TLR7 agonist) ANA773 (TLR7 agonist) GS9620 (TLR7 agonist) 2-O-methyl-modified RNA (TLR7 antagonist) |

| TLR9 | Activates MyD88 pathway, thereby producing nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) mediated proinflammatory cytokines. Suppresses Dcs and neutrophil recruitement and promotes macrophage uptake of pathogens in bacterial sepsis. Is also associated with effector functions of myeloid cells and with viral loads in viral sepsis. |

CPG10101 or Actilon™ (TLR9 agonist) IMO-2125 (TLR9 agonist) SD-101 (TLR9 agonist) |

| NOD-1 | NOD-1 senses a peptidoglycan-derived peptide D-gamma-Glu-mDAP (iEDAP) from all Gram-negative bacteria and a subset of Gram-positive bacteria, inducing its oligomerization and subsequent activation of NFkB and other effector pathways. NOD-1 activation leads to proinflammatory mediator production in collaboration with TLRs. NOD-1 is also a key innate immune trigger to drive the development of immunity. | KF1B (NOD-1 agonist) FK565 (NOD-1 Agonist) |

| NOD-2 | NOD-2 is expressed by epithelial cells and antigen-presenting cells and senses muramyldipeptide (MDP), a highly conserved peptidoglycan motif present in almost all bacteria, inducing its oligomerization and subsequent activation of NFkB and other effector pathways. | CL429 (NOD-2 agonist) |

| Dectin-1 | Dectin-1 recognizes β-(1,3)- glucan and is important in fungal sepsis. Dectin-1 signaling induces TLR-dependent and –independent signaling activation leading into phagocytosis, respiratory burst, and the production of various inflammatory mediators including IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-23 [64]. TLR-independent signal includes the activation of integrin Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) by Dectin-1. The proinflammatory cytokines are important to prime CD4+ T cells to differentiate into Th1/Th17 cells. |

β-glucan peptide (Dectin-1 agonist) |

| Dectin-2 | Dectin-2 recognizes α-mannose and is important for fungal sepsis. Dectin-2 forms a heterodimer with Dectin-3, important for Th17 immune responses. Dectin-2 KO mice are more susceptible to Candida albicans with less neutrophil recruitment and macrophage phagocytosis. |

Furfurman (Dectin-2 agonist) |

| RIG-I | RIG-I senses viral replication intermediates in infected cells. RIG-I signaling mediates protection against lethal viral dose. | ppp-RNA (M8. CBS-13-BPS, SLR10. SLR14) (RIG-I agonists) KIN131A (RIG-I agonist) |

| MDA-5 | Senses viral dsRNA | Poly (IC:LC) (MD5 and TLR3 agonist) rb-dsRNA (MD5 and TLR3 agonist) NAB2 (MD5 and TLR3 agonist) |

In Phase 3 trial, 1304 patients with severe sepsis received Eritoran-105 mg and 657 patients received placebo. In contrast to the Phase 2 trial, the 28-day mortality of Eritoran-105 mg group and placebo was 28.1% and 26.9%, respectively 43. Rather lower mortality in the placebo group than expected (i.e. less severe sepsis) and low circulating LPS levels in this cohort compared to the patients in Phase 2 trial were pointed out as potential explanation for the different results between Phase 2 and Phase 3 trial. The result from Phase 2 and Phase 3 trial is in line with the rodent studies mentioned above, where TLR4 deficiency offered a survival benefit by attenuating proinflammatory responses in severe sepsis, but worsened the outcome in less severe sepsis by impairing effector cell functions of myeloid cells. TLR4-MyD88 pathway controls proinflammatory cytokine production via NFκB signaling pathway, and effector functions such as phagocytosis via p38 signaling pathway 44 Thus, it may be important to block NFκB signaling via TLR4 specifically. This discussion may be applicable for TLR9 as well.

Flagellin administration, if high dose was not used, was beneficial to enhance CLP sepsis survival by augmenting macrophage effector functions. At high dose, however, significant proinflammatory responses caused organ injury. Thus, a case of TLR5 should be similar; avoiding significant activation of NFκB pathway is a key. Thus, approaches to directly target NF NFκB pathway via TLRs would be a potential approach. TRAF6 (TNF receptor associated factor 6)-TAK1(transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase-1)-IKK(IκB kinase)α/β are upstream signaling molecules for NFkB activation via TLRs 45. So far targeting these molecules have not been described yet.

In addition to TLR4, there is an increasing interest to target NOD-1 for infectious and non-infectious related multi-organ failure given that NOD-1 activation leads to proinflammatory mediator production in collaboration with TLRs 46. Given that NOD-1 is a key innate immune trigger to drive the development of adaptive immunity 47, however, a caution should be made to simply target NOD-1 as in the case of TLR4.

Fungal sepsis

Fungi are usually commensal. Although an estimated 5,000,000 fungal species exist in our environment, only 100-300 of them regularly infect humans 48,49. Fungi exhibit various morphologic states including spherical yeasts, molds with branching hyphae and pseudo-hyphae Since 1980, the prevalence of opportunistic fungal diseases has steadily increased in parallel to an increase in the number of individuals with acquired immune deficiencies or those receiving immune suppressive or myeloablative therapies 50. Among fungus, Candida species are by far the predominant cause of fungal sepsis accounting for 10% to 15% of health-care associated infections and 5% of all cases of sepsis 51. Invasive candidiasis has become the fourth leading cause of bloodstream infection, causing up to 40% mortality 52. Therefore, understanding our host immunological responses via PRRs will be important for the development of potential therapeutics.

Immunological responses in fungal sepsis

The cell wall of fungi predominantly comprises rigid polysaccharide layers. An inner layer consists of a chitin layer and an adjacent layer of β-(1,3) and β-(l,6)-glucans. An outer layer consists of N- and O-linked mannoses, β-glucans occupy 50% of the dry weight of the fungal cell wall 53. Innate responses to fungal pathogens are initiated by fungal component recognition via an array of PRRs including C-type lectin receptors (CLRs), TLRs and complement receptors By recognizing the fugal cell wall components, TLRs and CLRs play important roles in the initiation of innate immune response for the immediate control of fungal propagation, and the differentiation of CD4+ Th1 and Th17 cells for later control and long-term memory of fungal infection 48. TLR4 recognizes O-linked mannose 54, while TLR2 primarily recognizes cellular wall glycolipid component phospholipomannan 55. The major CLRs involved in antifungal recognition include Dectin-1, Dectin-2 and Dectin-3. Dectin-1 recognizes β-(1,3)- glucan, and Dectin-2 and Dectin-3 recognize α-mannose. Recruited neutrophils to the fungus-infected tissue perform reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) formation for pathogen clearance 56. DCs and monocytes can produce IL-23, which helps to promote T cell differentiation toward Th17. Th17 produces IL-17A and IL-17F, which interact with epithelial cells to produce β-defensins to kill fungus. Antibodies are also produced through fungal infection. However, antibodies that react with fungal antigens can be protective, neutral or disease-enhancing so that it is difficult to decipher their roles 57.

Because Candida species are major culprit for fungal infection, we will review PRR responses to Candida albicans here, primarily focusing on TLRs and CLRs. Netea et al. showed that C3H/HeJ mice, possessing a defective TLR4 due to the point mutation 58, were significantly more susceptible to Candida albicans compared to C3H/HeN control mice, which possess intact TLR4, associated with impaired chemokine (KC, MIP-2) expression and neutrophil recruitment 59. Interestingly, there was no significant change in proinflammatory cytokine levels between C3H/HeJ and C3H/HeN mice. There was also no difference in phagocytic ability between C3H/HeJ and C3H/HeN mice. TLR2 antibody administration did not affect KC and MIP-2 production, but attenuated the production of the proinflammatory cytokines instead. In contrast to the TLR4 experiment, the study by the same group showed that TLR2 KO mice were more resistant to Candida albicans, associated with less IL-10 level and less CD4+CD25+ Treg population 60. Interestingly, TNF-α and IL-1 production did not differ between WT and TLR2 KO mice. Detection of fungal ligands via TLR2 might have been compensated by other PRRs, while immunosuppressive IL-10 signal seemed to derive from TLR2. However, a study by Viliam on et al. showed that TLR2 KO mice were susceptible to Candida albicans infection 61. In this study, TLR2 KO mice were associated with less MIP-2 production and neutrophil recruitment. A study by Bellocchio et al. showed that fungal morphotypes (yeast vs hyphae) affected TLR2/4 signaling 62, which may potentially explain the difference in the results between these studies. MyD88 was found to be critical in fungal defense, as MyD88 KO mice were extremely sensitive to Candida infection 62. Specifically, MyD88 KO neutrophils showed impairment in killing ability and MyD88 KO DCs were ineffective to prime antifungal Th1 responses.

CLRs contain at least one C-type lectin-like domain and play a major role in fungal recognition. They are preferentially expressed on myeloid cells 63,64. Many studies have demonstrated that mutations or deletions in CLRs or downstream molecules lead to enhanced susceptibility to fungal infections, demonstrating their essentiality 48. Dectin-1 signaling induces TLR-dependent and –independent signaling activation leading into phagocytosis, respiratory burst, and the production of various inflammatory mediators including IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-23 65. TLR-independent signal includes the activation of integrin Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) by Dectin-1 66. The proinflammatory cytokines are important to prime CD4+ T cells to differentiate into Th1/Th17 cells. Dectin-1 KO mice demonstrated significant susceptibility to Candida albicans, associated with defective activation of tissue macrophages and subsequent innate immune responses 67 Dectin-2 forms a heterodimer with Dectin-3, important for Th17 immune responses 68. Dectin-2 KO mice were more susceptible to Candida albicans with less neutrophil recruitment and macrophage phagocytosis 69. In line with the result of Dectin-2 KO mice, Dectin-3 KO mice were also susceptible to Candida 70.

Therapeutic consideration

While in vivo results from TLRs were rather inconsistent, Dectin receptors have received a major interest regarding the development of therapeutics by targeting PRRs for fungal sepsis. For example, Dectin-1 Y298X is associated with susceptibility to Candida infection 71,72. Dectin-1 and-2 are essential for fungal defense and negatively regulated by E3 ubiquitin ligase Casitas B lymphoma-b (CBLB). In addition, kinase SYK, which is located at the downstream signaling of Dectin receptors, is negatively regulated by CBLB as well. Following fungal recognition, CBLB ubiquitinates SYK, Dectin-1 and Dectin-2 73. CBLB KO mice showed resistance to Candida infection with enhanced inflammasome activation, ROS production and increased fungal killing 73,74. Furthermore, the administration of cblb siRNA or a peptide inhibiting CBLB activity improved the outcome of Candida infection in mice, indicating that CBLB is a promising target 73,74. Other approaches to optimize Dectin receptor function should be also considered in the future.

Viral sepsis

Viral sepsis is likely under-represented among all sepsis. For example, a third of adult patients requiring ICU management for severe pneumonia had viral infections by PCR analysis 75. Patients with culture-negative sepsis had significantly lower levels of procalcitonin than those with documented sepsis 76. Furthermore, recent COVID-19 outbreak clearly demonstrated the seriousness of viral sepsis 77,78. Viruses can be divided into single-stranded RNA (ssRNA), double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), or DNA virus 79. Over 200 viruses are known to infect humans. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) and enterovirus are the most common viral causes of neonatal sepsis 80, while enterovirus is the most common cause of viral sepsis in young children. Influenza virus also causes a major morbidity and mortality in various age groups 4 HSV is DNA virus, and enterovirus and influenza virus are ssRNA virus.

Immunological responses in viral sepsis

TLR3, TLR7 and TLR9 detect extracellular viral RNAs and DNAs that enter the cell from the endocytic pathway. TLR3, TLR7, or TLR9 serves as a receptor for dsRNA, ssRNA, or DNA, respectively. TLR3 is expressed on macrophages and DCs along with epithelial cells 81. TLR7 is expressed on DCs 82. TLR9 is expressed on macrophages, DCs and B cells as above 17. In contrast, viral RNAs produced within a cell are sensed by a separate family of proteins called the RIG-I-like receptors including ssRNA sensor RIG-I and dsRNA sensor MDA-5 (melanoma differentiation-associated 5). While eukaryotic RNA undergoes 5’-capping in the nucleus, viral RNA is produced in the cytosol without this capping. Viral DNAs also activate cGAS (cyclic guanosine monophosphate-adenosine monophosphate synthase), then subsequently STING (stimulator of interferon genes). Eukaryotic DNA exists only in the nucleus, while viral DNA is in the cytosol. RIG-I-like receptors and cGAS exist in many cell types. An interaction of viral RNA and DNA with these PRRs will induce type I interferons (IFNs) that play a central role in driving an antiviral state. Type I IFNs consist of IFN-α, IFN-β, IFN-κ, IFN-ε and IFN-ω. IFN-α and IFN-β have been studied most. Plasmocytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) are the most efficient IFNs producing cells whose TLRs can recognize virus and produce IFNs up to 1,000 times more than other cells. Type I IFNs show anti-viral effects by a number of mechanisms; 1) Induction of endoribonuclease to degrade viral RNA, 2) induction of Mx (myxoma resistant) proteins to interfere with viral replication, 3) Increase of MHC I expression and antigen presentation by host cells, 4) Activation of NK cells and antigen presenting cells, and 5) Induction of T cell chemoattractants. Cytotoxic T cells can directly kill virus-infected cells. Helper T cells can help B cells to make antibodies against viruses.

The use of TLR9 in HSV genomic recognition is well characterized 83. Furthermore, TLR2 is also involved in HSV genomic recognition 84. Either TLR2 mice or TLR9 KO mice had viral loads comparable to WT mice, while TLR2/TLR9 double KO mice had significantly higher viral loads. Most cases of human Influenza are caused by influenza A and B viruses. Influenza A virus, for example, is recognized by TLR7 in the endosome and RIG-I in the cytosol 85. RIG-I replies on sensing of viral replication intermediates in infected cells such as airway epithelial cells, while detection of ssRNA by TLR7 on pDCs occurs without viral replication. Both TLR7 and RIG-I signaling mediates protection against lethal viral dose 85.

Therapeutic consideration

Current antiviral interventions focus on the use of direct-acting antivirals, which target the essential components in the life cycle of a virus 86. So far animal models demonstrated that adequate TLR and RLR function would be critical in the setting of viral infection. For example, a RIG-I agonist has been shown to work as vaccine adjuvants and antiviral therapy 86. TLR agonists also show protective effect against viral infection 87. However, it remains to be determined if rodent viral infection models recapitulate human viral sepsis, which is an important consideration when we target PRRs for viral sepsis.

Conclusion

Here we reviewed our host responses associated with PRRs in the setting of bacterial, fungal and viral sepsis. PRRs and downstream signaling pathways can offer overlapping, but some different roles depending on the severity of infection and the type of microbes. Furthermore, the majority of the studies to determine the role of PRRs in sepsis so far have been done using preclinical models. Understanding human immunological profiles in the setting of various sepsis will be critical to translate the findings in the preclinical studies to the development of therapeutic interventions.

Highlight.

Sepsis is a heterogeneous disease with an array of immunological responses.

Different combination of pattern recognition receptors is activated via diverse pathogens.

Pattern recognition receptors can be potential targets for sepsis.

Financial Support:

R21 HD099194 (K.Y., S.K.), R01 GM118277 (K.Y.)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest:

None

Contributor Information

Koichi Yuki, Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Cardiac Anesthesia Division, Boston Children’s Hospital; Department of Anaesthesia, Harvard Medical School; Department of Immunology, Harvard Medical School

Sophia Koutsogiannaki, Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Cardiac Anesthesia Division, Boston Children’s Hospital; Department of Anaesthesia, Harvard Medical School; Department of Immunology, Harvard Medical School

References

- 1.Eissa D, Carton EG & Buggy DJ Anaesthetic management of patients with severe sepsis. Br J Anaesth 105, 734–743, doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq305 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koutsogiannaki S et al. From the Cover: Prolonged Exposure to Volatile Anesthetic Isoflurane Worsens the Outcome of Polymicrobial Abdominal Sepsis. Toxicol Sci 156, 402–411, doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfw261 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singer M et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 315, 801–810, doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin GL, McGinley JP, Drysdale SB & Pollard AJ Epidemiology and Immune Pathogenesis of Viral Sepsis. Front Immunol 9, 2147, doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02147 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zahar JR et al. Outcomes in severe sepsis and patients with septic shock: pathogen species and infection sites are not associated with mortality. Crit Care Med 39, 1886–1895, doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31821b827c (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanco J et al. Incidence, organ dysfunction and mortality in severe sepsis: a Spanish multicentre study. Crit Care 12, R158, doi: 10.1186/cc7157 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi SH et al. Viral infection in patients with severe pneumonia requiring intensive care unit admission. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 186, 325–332, doi: 10.1164/rccm.201112-2240OC (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar S, Ingle H, Prasad DV & Kumar H Recognition of bacterial infection by innate immune sensors. Crit Rev Microbiol 39, 229–246, doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2012.706249 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mayr FB, Yende S & Angus DC Epidemiology of severe sepsis. Virulence 5, 4–11, doi: 10.4161/viru.27372 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vincent JL et al. International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. JAMA 302, 2323–2329, doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1754 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medzhitov R Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 1, 135–145, doi: 10.1038/35100529 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flo TH et al. Differential expression of Toll-like receptor 2 in human cells. J Leukoc Biol 69, 474–481 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliveira-Nascimento L, Massari P & Wetzler LM The Role of TLR2 in Infection and Immunity. Front Immunol 3, 79, doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00079 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaure C & Liu Y A comparative review of toll-like receptor 4 expression and functionality in different animal species. Front Immunol 5, 316, doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00316 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramos HC, Rumbo M & Sirard JC Bacterial flagellins: mediators of pathogenicity and host immune responses in mucosa. Trends Microbiol 12, 509–517, doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.09.002 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayashi F et al. The innate immune response to bacterial flagellin is mediated by Toll-like receptor 5. Nature 410, 1099–1103, doi: 10.1038/35074106 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eaton-Bassiri A et al. Toll-like receptor 9 can be expressed at the cell surface of distinct populations of tonsils and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Infect Immun 72, 7202–7211, doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.12.7202-7211.2004 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strober W, Murray PJ, Kitani A & Watanabe T Signalling pathways and molecular interactions of NOD1 and NOD2. Nat Rev Immunol 6, 9–20, doi: 10.1038/nri1747 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inohara N & Nunez G NODs: intracellular proteins involved in inflammation and apoptosis. Nat Rev Immunol 3, 371–382, doi: 10.1038/nri1086 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou H et al. Activation of Both TLR and NOD Signaling Confers Host Innate Immunity-Mediated Protection Against Microbial Infection. Front Immunol 9, 3082, doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.03082 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Poll T, van de Veerdonk FL, Scicluna BP & Netea MG The immunopathology of sepsis and potential therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Immunol 17, 407–420, doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.36 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rittirsch D, Huber-Lang MS, Flierl MA & Ward PA Immunodesign of experimental sepsis by cecal ligation and puncture. Nat Protoc 4, 31–36, doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.214 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alves-Filho JC et al. Regulation of chemokine receptor by Toll-like receptor 2 is critical to neutrophil migration and resistance to polymicrobial sepsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 4018–4023, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900196106 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zou L, Feng Y, Zhang M, Li Y & Chao W Nonhematopoietic toll-like receptor 2 contributes to neutrophil and cardiac function impairment during polymicrobial sepsis. Shock 36, 370–380, doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182279868 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zou L et al. Toll-like receptor 2 plays a critical role in cardiac dysfunction during polymicrobial sepsis. Crit Care Med 38, 1335–1342, doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181d99e67 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoshino K et al. Cutting edge: Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient mice are hyporesponsive to lipopolysaccharide: evidence for TLR4 as the Lps gene product. J Immunol 162, 3749–3752 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roger T et al. Protection from lethal gram-negative bacterial sepsis by targeting Toll-like receptor 4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 2348–2352, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808146106 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lorenz E, Hallman M, Marttila R, Haataja R & Schwartz DA Association between the Asp299Gly polymorphisms in the Toll-like receptor 4 and premature births in the Finnish population. Pediatr Res 52, 373–376, doi: 10.1203/00006450-200209000-00011 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Opal SM et al. Relationship between plasma levels of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and LPS-binding protein in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. J Infect Dis 180, 1584–1589, doi: 10.1086/315093 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marshall JC et al. Diagnostic and prognostic implications of endotoxemia in critical illness: results of the MEDIC study. J Infect Dis 190, 527–534, doi: 10.1086/422254 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deng M et al. Lipopolysaccharide clearance, bacterial clearance, and systemic inflammatory responses are regulated by cell type-specific functions of TLR4 during sepsis. J Immunol 190, 5152–5160, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300496 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andonegui G et al. Endothelium-derived Toll-like receptor-4 is the key molecule in LPS-induced neutrophil sequestration into lungs. J Clin Invest 111, 1011–1020, doi: 10.1172/JCI16510 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alves-Filho JC, de Freitas A, Russo M & Cunha FQ Toll-like receptor 4 signaling leads to neutrophil migration impairment in polymicrobial sepsis. Crit Care Med 34, 461–470 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang X et al. Flagellin attenuates experimental sepsis in a macrophage-dependent manner. Crit Care 23, 106, doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2408-7 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiao Y et al. Over-activation of TLR5 signaling by high-dose flagellin induces liver injury in mice. Cell Mol Immunol 12, 729–742, doi: 10.1038/cmi.2014.110 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plitas G, Burt BM, Nguyen HM, Bamboat ZM & DeMatteo RP Toll-like receptor 9 inhibition reduces mortality in polymicrobial sepsis. J Exp Med 205, 1277–1283, doi: 10.1084/jem.20080162 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Albiger B et al. Toll-like receptor 9 acts at an early stage in host defence against pneumococcal infection. Cell Microbiol 9, 633–644, doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00814.x (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feng Y et al. MyD88 and Trif signaling play distinct roles in cardiac dysfunction and mortality during endotoxin shock and polymicrobial sepsis. Anesthesiology 115, 555–567, doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31822a22f7 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sonego F et al. MyD88-, but not Nod1- and/or Nod2-deficient mice, show increased susceptibility to polymicrobial sepsis due to impaired local inflammatory response. PLoS One 9, e103734, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103734 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nunez G Intracellular sensors of microbes and danger. Immunol Rev 243, 5–8, doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01058.x (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deshmukh HS et al. Critical role of NOD2 in regulating the immune response to Staphylococcus aureus. InfectImmun 77, 1376–1382, doi: 10.1128/IAI.00940-08 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tidswell M et al. Phase 2 trial of eritoran tetrasodium (E5564), a toll-like receptor 4 antagonist, in patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med 38, 72–83, doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b07b78 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Opal SM et al. Effect of eritoran, an antagonist of MD2-TLR4, on mortality in patients with severe sepsis: the ACCESS randomized trial. JAMA 309, 1154–1162, doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2194 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Skjesol A et al. The TLR4 adaptor TRAM controls the phagocytosis of Gram-negative bacteria by interacting with the Rab11-family interacting protein 2. PLoS Pathog 15, e1007684, doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007684 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kawai T & Akira S Signaling to NF-kappaB by Toll-like receptors. Trends Mol Med 13, 460–469, doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.09.002 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moreno L & Gatheral T Therapeutic targeting of NOD1 receptors. Br J Pharmacol 170, 475–485, doi: 10.1111/bph.12300 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fritz JH et al. Nod1-mediated innate immune recognition of peptidoglycan contributes to the onset of adaptive immunity. Immunity 26, 445–459, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.009 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lionakis MS & Levitz SM Host Control of Fungal Infections: Lessons from Basic Studies and Human Cohorts. Annu Rev Immunol 36, 157–191, doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053318 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Templeton SP, Rivera A, Hube B & Jacobsen ID Editorial: Immunity to Human Fungal Pathogens: Mechanisms of Host Recognition, Protection, Pathology, and Fungal Interference. Front Immunol 9, 2337, doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02337 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Richardson M & Lass-Florl C Changing epidemiology of systemic fungal infections. Clin Microbiol Infect 14 Suppl 4, 5–24, doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.01978.x (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Delaloye J & Calandra T Invasive candidiasis as a cause of sepsis in the critically ill patient. Virulence 5, 161–169, doi: 10.4161/viru.26187 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kullberg BJ & Arendrup MC Invasive Candidiasis. N Engl J Med 373, 1445–1456, doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1315399 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Calderone RA & Braun PC Adherence and receptor relationships of Candida albicans. Microbiol Rev 55, 1–20 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Netea MG et al. Immune sensing of Candida albicans requires cooperative recognition of mannans and glucans by lectin and Toll-like receptors. J Clin Invest 116, 1642–1650, doi: 10.1172/JCI27114 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jouault T et al. Candida albicans phospholipomannan is sensed through toll-like receptors. J Infect Dis 188, 165–172, doi: 10.1086/375784 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Romani L et al. An immunoregulatory role for neutrophils in CD4+ T helper subset selection in mice with candidiasis. J Immunol 158, 2356–2362 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Casadevall A & Pirofski LA Immunoglobulins in defense, pathogenesis, and therapy of fungal diseases. Cell Host Microbe 11, 447–456, doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.04.004 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Poltorak A et al. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science 282, 2085–2088, doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Netea MG et al. The role of toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR4 in the host defense against disseminated candidiasis. J Infect Dis 185, 1483–1489, doi: 10.1086/340511 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Netea MG et al. Toll-like receptor 2 suppresses immunity against Candida albicans through induction of IL-10 and regulatory T cells. J Immunol 172, 3712–3718, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3712 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Villamon E et al. Toll-like receptor-2 is essential in murine defenses against Candida albicans infections. Microbes Infect 6, 1–7, doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2003.09.020 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bellocchio S et al. The contribution of the Toll-like/IL-1 receptor superfamily to innate and adaptive immunity to fungal pathogens in vivo. J Immunol 172, 3059–3069, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.3059 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sancho D & Reis e Sousa C Signaling by myeloid C-type lectin receptors in immunity and homeostasis. Annu Rev Immunol 30, 491–529, doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101352 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zelensky AN & Gready JE The C-type lectin-like domain superfamily. FEBS J 272, 6179–6217, doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05031.x (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tang J, Lin G, Langdon WY, Tao L & Zhang J Regulation of C-Type Lectin Receptor-Mediated Antifungal Immunity. Front Immunol 9, 123, doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00123 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li X et al. The beta-glucan receptor Dectin-1 activates the integrin Mac-1 in neutrophils via Vav protein signaling to promote Candida albicans clearance. Cell Host Microbe 10, 603–615, doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.009 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Taylor PR et al. Dectin-1 is required for beta-glucan recognition and control of fungal infection. Nat Immunol 8, 31–38, doi: 10.1038/ni1408 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bi L et al. CARD9 mediates dectin-2-induced IkappaBalpha kinase ubiquitination leading to activation of NF-kappaB in response to stimulation by the hyphal form of Candida albicans. J Biol Chem 285, 25969–25977, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.131300 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ifrim DC et al. The Role of Dectin-2 for Host Defense Against Disseminated Candidiasis. JInterferon Cytokine Res 36, 267–276, doi: 10.1089/jir.2015.0040 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhu LL et al. C-type lectin receptors Dectin-3 and Dectin-2 form a heterodimeric pattern-recognition receptor for host defense against fungal infection. Immunity 39, 324–334, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.017 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Plantinga TS et al. Early stop polymorphism in human DECTIN-1 is associated with increased candida colonization in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis 49, 724–732, doi: 10.1086/604714 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Usluogullari B et al. The role of Human Dectin-1 Y238X Gene Polymorphism in recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis infections. Mol Biol Rep 41, 6763–6768, doi: 10.1007/s11033-014-3562-2 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wirnsberger G et al. Inhibition of CBLB protects from lethal Candida albicans sepsis. Nat Med 22, 915–923, doi: 10.1038/nm.4134 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xiao Y et al. Targeting CBLB as a potential therapeutic approach for disseminated candidiasis. Nat Med 22, 906–914, doi: 10.1038/nm.4141 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dolin HH, Papadimos TJ, Chen X & Pan ZK Characterization of Pathogenic Sepsis Etiologies and Patient Profiles: A Novel Approach to Triage and Treatment. Microbiol Insights 12, 1178636118825081, doi: 10.1177/1178636118825081 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Phua J et al. Characteristics and outcomes of culture-negative versus culture-positive severe sepsis. Crit Care 17, R202, doi: 10.1186/cc12896 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li H et al. SARS-CoV-2 and viral sepsis: observations and hypotheses. Lancet 395, 1517–1520, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30920-X (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yuki K, Fujiogi M & Koutsogiannaki S COVID-19 pathophysiology: A review. Clin Immunol 215, 108427, doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108427 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stetson DB & Medzhitov R Type I interferons in host defense. Immunity 25, 373–381, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.007 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shane AL, Sanchez PJ & Stoll BJ Neonatal sepsis. Lancet 390, 1770–1780, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31002-4 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ding X et al. TLR4 signaling induces TLR3 up-regulation in alveolar macrophages during acute lung injury. Sci Rep 7, 34278, doi: 10.1038/srep34278 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Larange A, Antonios D, Pallardy M & Kerdine-Romer S TLR7 and TLR8 agonists trigger different signaling pathways for human dendritic cell maturation. J Leukoc Biol 85, 673–683, doi: 10.1189/jlb.0808504 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lund J, Sato A, Akira S, Medzhitov R & Iwasaki A Toll-like receptor 9-mediated recognition of Herpes simplex virus-2 by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Exp Med 198, 513–520, doi: 10.1084/jem.20030162 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sorensen LN et al. TLR2 and TLR9 synergistically control herpes simplex virus infection in the brain. J Immunol 181, 8604–8612, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8604 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pang IK, Pillai PS & Iwasaki A Efficient influenza A virus replication in the respiratory tract requires signals from TLR7 and RIG-I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 13910–13915, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303275110 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yong HY & Luo D RIG-I-Like Receptors as Novel Targets for Pan-Antivirals and Vaccine Adjuvants Against Emerging and Re-Emerging Viral Infections. Front Immunol 9, 1379, doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01379 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Carty M & Bowie AG Recent insights into the role of Toll-like receptors in viral infection. Clin Exp Immunol 161, 397–406, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04196.x (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]