Abstract

Migrants in countries affiliated with the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have a higher risk of acquiring HIV, experience delayed HIV diagnosis, and have variable levels of engagement with HIV care and treatment when compared to native-born populations. A systematic mixed studies review was conducted to generate a multilevel understanding of the barriers and facilitators affecting HIV Care Cascade steps for migrant people living with HIV (MLWH) in OECD countries. Medline, Embase, Scopus, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Library were searched on March 25, 2020. Screening, critical appraisal, and analysis were conducted independently by two authors. We used qualitative content analysis and the five-level Socio-Ecological Model (i.e., individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and policy) to categorize barriers and facilitators. Fifty-nine studies from 17 OECD countries were included. MLWH faced similar barriers and facilitators regardless of their host country, ethnic and geographic origins, or legal status. Most barriers and facilitators were associated with the individual and organizational levels and centered around retention in HIV care and treatment. Adapting clinical environments to better address MLWH's competing needs via multidisciplinary models would address retention issues across OECD countries.

Keywords: HIV, migrants, systematic mixed studies review, HIV Care Cascade, OECD, Socio-Ecological Model

Introduction

As of 2019, an estimated 272 million people moved to a new country temporarily or permanently.1 Over half (55%) of all international migrants moved to 1 of 12 countries, 9 of which are members of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).2 The OECD connects 38 countries from around the world (e.g., Canada, France, Germany, Japan, Switzerland, United States), 34 of which are listed as high income countries and 4 as upper middle income countries according to the World Bank.3,4 The OECD identifies standards, programs, and initiatives to drive and anchor reform globally.4 In addition, country reviews and data provided by the OECD give member countries an opportunity to inform policy decisions and encourage better performance.4

Migrant people living with HIV (MLWH) in OECD and other high-income countries account for increasing proportions of new HIV diagnoses in these countries. They also experience delayed entry into HIV care and have poorer HIV-related outcomes when compared to native-born populations in their host country.5–13 An extensive body of literature indicates that MLWH in these countries face numerous barriers that hinder their HIV testing.14–25 This knowledge is critical for understanding what strategies are needed to improve HIV diagnosis and status awareness in MLWH.

However, HIV testing is only the first step to engagement with HIV care as proposed in the HIV Care Cascade (HCC).26–29 The HCC is a public health model that represents key steps in HIV care, including diagnosis, linkage to care, treatment provision, retention in care, and achievement of viral suppression.26–29 The HCC is generally used as a population-level aggregate to cross-sectionally understand engagement with HIV care.26–29 It can be particularly useful in visualizing global efforts toward the 95-95-95 targets set by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), where 95% of people living with HIV know their status, 95% of those individuals are receiving treatment, and 95% of those on treatment have a suppressed viral load by the year 2030, which could stop forward transmission.30

To meet the overarching goal of eliminating HIV/AIDS as a public health threat by 2030, it is necessary to identify the barriers and facilitators that MLWH in OECD countries encounter within the context of the HCC, beyond diagnosis. A preliminary review of the literature7 has been published, which presents challenges faced by MLWH in high-income countries to engage in HIV care as well as possible avenues for action. However, a rigorous and comprehensive systematic review using a multilevel lens to understand the factors identified is still lacking. This study attempts to fill that gap.

Methods

Protocol and registration

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement and associated Checklist were used to develop this review.31 A systematic mixed studies review (SMSR) using a data-based convergent design was conducted.32–35 A protocol of this SMSR was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42020172122) and published in open-access format.36

Study design

SMSRs enable the synthesis of data from studies with diverse research designs, including qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods.32–35 By bringing together qualitative and quantitative data, a greater understanding can be achieved than would be gained by analyzing either type of data alone. These reviews consist of six steps: (1) develop a review question; (2) define eligibility criteria; (3) develop and apply an extensive search strategy; (4) identify and select relevant studies; (5) appraise the quality of included studies; and (6) synthesize data from included studies.34,35

Review question

The review question was what are the barriers and facilitators that MLWH in OECD countries encounter in relationship to the steps of the HCC beyond diagnosis?

Eligibility criteria

Study characteristics

We included primary empirical studies using qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method designs in this review and excluded literature reviews, methodological, theoretical, commentary, and articles that involved simulations or modeling approaches. Initially, we set no limit for language as OECD countries have different official languages.36 However, substantial changes in our resources (i.e., team-member availabilities) arose as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, we retained only studies published in English.

Population

Migrants include all people who relocate temporarily or permanently to countries irrespective of a reason for translocation.36–38 We included studies that are explicitly focused, either partially or completely, on MLWH living in any of the 38 OECD countries, irrespective of their age.4,36 If studies collected data on multiple populations (e.g., nonmigrants and migrant populations), subanalyses specific to MLWH were required for retention. For qualitative studies, deciphering if a subanalysis was conducted can be difficult. In these cases, only results that explicitly referred to international migrants were imported into our amalgamated dataset.

Outcomes

We defined barriers and facilitators as any factors that were reported to impact one or more HCC steps beyond diagnosis.26–28 To facilitate integration of data from studies with no explicit reference to MLWH engagement with HCC steps, we categorized factors into three groups, those that impact (1) initial linkage to care and treatment provision; (2) retention in care and in treatment; and (3) achievement and/or maintenance of an undetectable HIV viral load.

Search strategy

An academic librarian collaborated in developing a comprehensive search strategy. We searched Medline, Embase, Scopus, CINAHL, and Cochrane Library on March 25, 2020. See the protocol and its associated supplementary appendix for the full search strategy implemented in each database.36

Screening

Screening was done in two phases. In the first phase, the first author (A.K.A.) imported all records identified into EndNote V.X9.3.3 and screened all titles and abstracts. Three other authors (D.L., K.K.V.M., and A.R.-C.) each independently completed 33% of the title and abstract screening. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus. Records deemed eligible following title and abstract screening were then included for the full-text review (phase 2), which was completed independently by A.K.A. and D.O.-P. Weekly meetings to address any disagreements were held. An agreement score (number of agreed articles/total number of articles) between the two reviewers was calculated, as well as interrater reliability according to Cohen's Kappa.39

Critical appraisal

A.K.A. and D.O.-P. each independently appraised the quality of all retained studies with the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). The MMAT is a valid and reliable tool for quality assessment in SMSRs.34,35,40–43 All studies were included even after critical appraisal regardless of their methodological quality. Studies with poor quality were identified and labeled accordingly in the Results section.

Data extraction, synthesis, and analysis

A data-based convergent design was used, in which qualitative and quantitative data were integrated in the synthesis phase.32 All data were extracted by the first author and verified by D.O.-P. Data were imported into Microsoft Excel©. Data included author(s), year of publication, study design, country of publication, and demographic characteristics of the MLWH studied (i.e., immigration status, ethnic backgrounds, geographic origins, and gender or sex, if specified), and the factors affecting HCC steps. The quantitative data extraction phase involved an analytic process whereby all statistically significant results based on p values and confidence intervals were classified as different types of barriers and facilitators.

Qualitative content analysis, using the conventional approach by Hsieh and Shannon,44 was then conducted independently by the first author and verified by D.O.-P. and in research team and stakeholder engagement meetings. A hybrid approach to analysis was taken, where all barriers and facilitators from quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies were first grouped under inductively developed categories and then deductively linked to HCC steps.

To establish a multilevel understanding, factors were also linked to levels of the Socio-Ecological Model, which consists of five levels: individual (i.e., personal characteristics and factors that influence behaviors), interpersonal (i.e., relationships with others), organizational (i.e., clinical settings, hospitals, and health systems), community (i.e., broader social factors such as cultural values), and policy (i.e., laws and regulations).45–47 Descriptive statistics were produced to depict trends found in the demographic data, as well as in the frequencies of barrier and facilitator categories.

Patient engagement in research

Patient engagement in research involves the active collaboration of patients in governance, priority setting, the overall conduct of research, and knowledge translation.48,49 This approach enables direct dialogue and equitable partnerships between patients and researchers, grounded in values such as trust and reciprocity. Patient engagement can improve the relevance of research to patients, increase uptake of results, and facilitate knowledge translation in concerned communities.48–53

As such, four MLWH living in Canada were engaged in this review as stakeholders. The MLWH included a refugee from Africa, an asylum seeker from Africa, an international student from Asia, and an international student from Western Europe. Six stakeholder engagement meetings were held virtually with the MLWH between March and December 2020.

Initially, the MLWH acted as consultants, assisting in guiding the different aspects of the review via their experiences with migration and living with HIV. However, after the second meeting, the MLWH acted as collaborators. They each completed 5% of the title and abstract screening and 5% of the full-text screening for knowledge (i.e., HIV-related information) and skill (i.e., how to conduct research and more specifically, phases of literature review studies) development.36 Workshops were provided by the first author to train them. The MLWH also provided feedback during the analysis and interpretation phase to provide nuance to the results via their lived experiences. See the protocol for more details.36

Ethics statement

Systematic reviews do not require research ethics approval. However, as patients were engaged in this study, ethics approval was obtained from the McGill University Health Centre (15-188-MUHC, 2016-1697, eReviews 4688).

Results

Eligible studies and interrater reliability

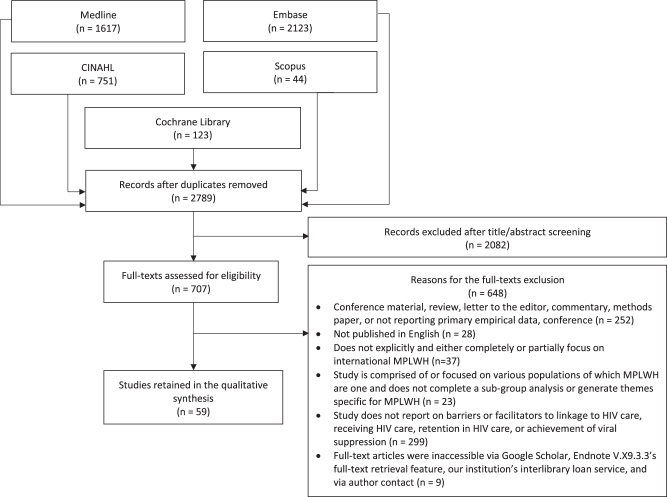

A total of 2789 records were identified after the exclusion of duplicates. Title and abstract screening left 707 records to be full-text reviewed. Ultimately, 59 studies were retained.54–112 Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flow diagram, which depicts the process of including and excluding studies. Agreement between A.K.A. and D.O.-P. for the full-text review was 94%. Interrater reliability according to Cohen's Kappa was 0.64 suggesting a moderate level of agreement.

FIG. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of retained and excluded studies. MPLWH, migrant people living with HIV; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Critical appraisal of retained articles

The critical appraisal showed that 51 of 59 studies (86%) were of high quality (i.e., MMAT summative score above 85%), while 7 (12%) were of moderate quality (i.e., summative score between 70% and 84%) and 1 study (2%) was of poor quality (i.e., summative score of 57%). The critical appraisal of qualitative studies was most often impacted by low credibility and confirmability (i.e., insufficient evidence that findings were grounded in the data). For quantitative studies, incomplete or inadequate reporting of the statistical analysis (e.g., not addressing all confounders) most impacted the quality assessment. Mixed methods studies were impacted by poor justification for their study design or had inadequate integration of qualitative and quantitative data. Refer to Table 1 for responses to each MMAT question and respective summative scores. For improved readability, only 33 of the 59 studies that failed to meet at least one quality assessment criteria according to the tool are presented in Table 1 (the other 26 studies met all quality assessment criteria completely and are thus not presented in the Table 1).

Table 1.

Critical Appraisal of Retained Studies Using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool

| In-text citation | Screening questions |

1. Qualitative studies |

3. Nonrandomized studies |

4. Quantitative descriptive studies |

5. Mixed methods studies |

Total score | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SQ.1 | SQ.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.3 | 5.4 | 5.5 | ||

| 56 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 65 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | — | — | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 72 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | No | Yes | — | — | — | 5/7 | ||||||||||||

| 73 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 75 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 77 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | — | — | — | 5/7 | ||||||||||||

| 81 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 82 | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | 4/7 | ||||||||||||

| 87 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 89 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | — | — | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 97 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 99 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 100 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 102 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 105 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | No | Yes | — | — | — | 5/7 | ||||||||||||

| 107 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 55 | Yes | Yes | — | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | — | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 62 | Yes | Yes | — | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Can't tell | — | — | 5/7 | ||||||||||||

| 64 | Yes | Yes | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Can't tell | — | — | 5/7 | ||||||||||||

| 69 | Yes | Yes | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | — | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 74 | Yes | Yes | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | — | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 76 | Yes | Yes | — | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | — | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 91 | Yes | Yes | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | — | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 98 | Yes | Yes | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | — | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 103 | Yes | Yes | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | — | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 104 | Yes | Yes | — | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | — | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 108 | Yes | Yes | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | — | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 110 | Yes | Yes | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | — | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 111 | Yes | Yes | — | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | — | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 67 | Can't tell | Yes | — | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | — | 6/7 | ||||||||||||

| 83 | Yes | Yes | — | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Can't tell | — | 5/7 | ||||||||||||

| 61 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 16/17 | ||||

| 78 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | — | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 14/17 | ||||

Of the 59 retained studies, only 33 are presented where at least one item in the tool did not receive a “Yes” (i.e., studies that did not receive a perfect score are shown). Note that no study in the retained set of articles applied a randomized controlled design. As such, the questions associated with randomized designs (labeled #3 in the original MMAT tool) are not presented.

MMAT, Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool.

Demographic data

Table 2 depicts the characteristics of included studies, grouped by OECD countries. Notably, included studies were published in 17 OECD countries between 1999 and 2020. The majority of the studies were published in the United States (22/59; 37%), followed by the United Kingdom (10/59; 17%), and France (6/59; 10%). Only one study was multinational and reported data from several OECD countries.76 Designs of the retained studies were qualitative (36/59; 61%), nonrandomized experimental (16/59; 27%), quantitative descriptive (3/59; 5%), and mixed methods (4/59; 7%).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Included Studies in This Systematic Review, Presented by Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development Country

| In-text citation Nos. | Author(s) | Year | Study design | Migrant population as described in retained studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States (n = 22) | ||||

| 58 | Arnold et al. | 2020 | Qualitative | Immigrants from various ethnic and racial backgrounds |

| 60 | Barrington et al. | 2019 | Qualitative | Gay Latino immigrant men with documentation status for participants classified as “Not clear; US Citizen; or Undocumented” |

| 61 | Barsky and Albertini | 2006 | Mixed methods | Caribbean (Haitian) Americans living in the United States for <5 to >20 years |

| 63 | Bowden et al. | 2006 | Qualitative | Latinx |

| 68 | Chin et al. | 2006 | Mixed methods | Asian and Pacific Islanders with immigration status classified as either “Undocumented” or “Documented and US citizen” |

| 70 | Dang et al. | 2012 | Qualitative | Undocumented Latinx immigrants |

| 77 | Foley | 2005 | Qualitative | African Immigrant women |

| 79 | Fuller et al. | 2020 | Qualitative | Immigrants |

| 82 | Johansen | 2006 | Qualitative | Latina migrant trafficking victim |

| 84 | Kang et al. | 2003 | Qualitative | Asian undocumented, noncitizens |

| 86 | Levison et al. | 2017 | Qualitative | Latinx immigrants |

| 89 | Martin et al. | 2013 | Qualitative | Undocumented migrants |

| 91 | Mishreki et al. | 2020 | Non-randomized | Migrant detainees from various geographic locations |

| 95 | Ojikutu et al. | 2018 | Qualitative | African born women with immigration status classified as “undocumented; asylee; permanent resident; or other” |

| 97 | Othieno | 2007 | Qualitative | African born immigrants and refugees |

| 99 | Pivnick et al. | 2010 | Qualitative | English speaking Caribbean immigrants (documented and undocumented) |

| 100 | Remien et al. | 2015 | Qualitative | African immigrants |

| 101 | Ross et al. | 2019 | Qualitative | Undocumented African immigrants |

| 102 | Russ et al. | 2012 | Qualitative | Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, foreign-born, categorized into the following citizenship categories “US citizens or Permanent residents” |

| 103 | Saint-Jean et al. | 2011 | Non-randomized | Caribbean (Haitian) immigrants |

| 105 | Shedlin and Shulman | 2004 | Qualitative | Dominican, Mexican, and Central American immigrants |

| 112 | Vissman et al. | 2011 | Qualitative | Immigrant Latinx |

| United Kingdom (n = 10) | ||||

| 56 | Allan and Clarke | 2005 | Qualitative | Asylum seekers |

| 57 | Anderson an Doyal | 2004 | Qualitative | African women self-classified as Black that lived in the United Kingdom for at least 6 months |

| 65 | Burns et al. | 2007 | Qualitative | African migrants |

| 72 | Doyal and Anderson | 2005 | Qualitative | Sub-Saharan African women |

| 73 | Doyal et al. | 2009 | Qualitative | Heterosexual African men |

| 75 | Erwin and Peters | 1999 | Qualitative | Africans |

| 83 | Jones et al. | 2019 | Quantitative descriptive | Clinicians encountering refugees, asylum seekers and/or undocumented migrants |

| 93 | Ndirangu and Evans | 2009 | Qualitative | African women—immigration/visa status was indicated by mentioning that two participants were students, four were asylum seekers and two were entitled to settle permanently in the United Kingdom |

| 96 | Orton et al. | 2012 | Qualitative | Asylum seekers from Africa (25/26 participants) and Brazil (1/26) |

| 106 | Spiers et al. | 2016 | Qualitative | Black African women |

| France (n = 6) | ||||

| 54 | Abgrall et al. | 2013 | Non-randomized | Sub-Saharan Africans |

| 55 | Abgrall et al. | 2019 | Nonrandomized | Migrants are those individuals that are either born outside of France without French nationality, or those who arrived in France when they were >15 years of age and have received French nationality |

| 92 | Morel | 2019 | Qualitative | Recently arrived immigrants |

| 88 | Doue and Roussiau | 2016 | Nonrandomized | sub-Saharan Africa migrants |

| 110 | Vignier et al. | 2018 | Nonrandomized | Migrants born in Sub-Saharan Africa with the following resident permit at arrival “none; temporary; resident permit; or French nationality” |

| 111 | Vignier et al. | 2019 | Nonrandomized | Migrants born in sub-Saharan Africa with the following resident permit at arrival “none; temporary; resident permit; or French nationality” |

| Australia (n = 3) | ||||

| 81 | Herrmann et al. | 2012 | Qualitative | Migrants from various countries of origin and ethnicities and with their visa status classified as either “457 long stay business visa; student; spousal; other; permanent resident; or New Zealand citizen” |

| 85 | Körner | 2007 | Qualitative | Migrants born overseas and moved to Australia as temporary or permanent residents for various situations, including work, family, humanitarian, and educational purposes |

| 98 | Petoumenos et al. | 2015 | Nonrandomized | Temporary residents originating from various geographic regions with the following visa types: bridging, other, spouse, student, and working |

| Canada (n = 3) | ||||

| 71 | dela Cruz et al. | 2020 | Mixed methods | Sub-Saharan African immigrants |

| 87 | Logie et al. | 2016 | Qualitative | African and Caribbean lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender newcomers and refugees |

| 64 | Bunn et al. | 2013 | Nonrandomized | Landed immigrants (3-month waiting period), those with no permanent resident status, and those considered foreign visitors |

| Israel (n = 3) | ||||

| 69 | Cohen et al. | 2007 | Nonrandomized | Ethiopian Jewish immigrants |

| 74 | Elbirt et al. | 2014 | Nonrandomized | Immigrants from Ethiopia |

| 67 | Chemtob et al. | 2019 | Quantitative descriptive | Undocumented migrants from various geographic regions |

| Netherlands (n = 3) | ||||

| 62 | Bil et al. | 2019 | Nonrandomized | Migrants >18 years, foreign-born and resident in the country of recruitment for >6 months—categorized as originating from various geographic origins—immigration status classified as permanent residency permit; temporary residency permit; and refugee status/unknown |

| 107 | Stutterheim et al. | 2012 | Qualitative | Africans and Afro-Caribbean (Antillean and Surinamese) |

| 108 | Sumari-de Boer et al. | 2012 | Nonrandomized | Immigrants from various geographic origins (primarily from sub-Sahara Africa, Surinam, and the Dutch Antilles) |

| Spain (n = 2) | ||||

| 80 | Guionnet et al. | 2014 | Qualitative | Immigrant women originating from various countries |

| 94 | Ndumbi et al. | 2018 | Quantitative descriptive | Migrants originating from various countries and continents with immigration status classified as “national/resident or irregular status” |

| Belgium (n = 1) | ||||

| 59 | Arrey et al. | 2017 | Qualitative | Sub-Saharan African migrant women |

| Ireland (n = 1) | ||||

| 78 | Foreman and Hawthorne | 2007 | Mixed methods | Migrants that originated from outside the European Union—indication of participant status (refugee, in asylum process, and “leave to remain” application) was indicated |

| Italy (n = 1) | ||||

| 104 | Saracino et al. | 2014 | Non-randomized | Migrants were those born outside Italy, based on geographical origin, derived from nationality or from country of birth/origin |

| Japan (n = 1) | ||||

| 66 | Castro-Vázquez and Tarui | 2007 | Qualitative | Latin American (Brazilian and Peruvian) men |

| Sweden (n = 1) | ||||

| 90 | Mehdiyar et al. | 2016 | Qualitative | Migrants from various continents living in Sweden for 2–20 years |

| Switzerland (n = 1) | ||||

| 109 | Thierfelder et al. | 2012 | Non-randomized | Immigrants from various geographic origins |

| Multinational study including: Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and the United Kingdom (n = 1) | ||||

| 76 | Fakoya et al. | 2017 | Non-randomized | Migrants living in Europe with permanent residency; temporary residency; asylum seeker or refugee status; undocumented status; or unknown from >1 geographic region and ethnicity |

The majority of retained studies (53/59; 90%) reported the ethnic backgrounds or geographic origins (e.g., country of birth) of the MLWH whom they focused on. Most studies focused on people of African origin (21/53; 40%), mostly from the sub-Saharan region, followed by Latin American (henceforth Latinx; 7/53; 13%), Caribbean (3/53; 6%), and Asian and Pacific Islander (3/53; 6%) populations. The remaining studies (19/53; 36%) focused on populations composed of MLWH with different ethnic backgrounds or geographic origin. Of these 19 studies, 11 (58%) were published in European countries.

Over half of the studies (31/59; 53%) did not report the immigration or legal status of MLWH. Among those that did, six (21%) focused only on undocumented MLWH, two (7%) on asylum seekers, and one (4%) on temporary visa holders. The remaining studies (19/28; 68%) focused on MLWH with more than one immigration or legal status. Notably, the majority of studies (46/59; 78%) were not gender or sex specific. However, nine studies (15%) focused solely on women, two (3%) on men, one (2%) on men who have sex with men, and one (2%) on people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer (LGBTQ+).

Barriers—key descriptive trends

Nineteen categories of barriers were identified. These barrier categories were reported a total of 225 times across the 59 retained studies. The most reported barrier categories were fear (22/59; 37%), competing priorities (18/59; 31%), language issues (16/59; 27%), and inadequate clinical environments (22/59; 37%). Barriers could be attributed to multiple levels of the Socio-Ecological Model and steps of the HCC. Regarding the Socio-Ecological Model, most reported barriers were attributed to the individual (145/225; 64%) and organizational levels (44/225; 20%). For steps of the HCC, most reported barriers were found to be associated with retention (176/257; 68%), compared to linkage to care (77/257; 30%). Barriers pertaining directly to the achievement of viral suppression were rarely reported (4/257; 2%). No apparent patterns were identified by country or year. See Table 3 for a cross-map of barrier categories with examples for each Socio-Ecological Model level and step of the HCC.

Table 3.

Barrier Categories with Examples Cross-Mapped to the Levels of the Socio-Ecological Model and Steps of the HIV Care Cascade

| Individual | Interpersonal | Organizational | Community | Policy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linkage | Fear Of accessing care; disclosure; deportation; incarceration; isolation, stigma, and termination of employment56,60,61,63,75,82,86,95,97,100,101,112 Lack of knowledge Lack of understanding of the health and social system; unfamiliarity with biomedicine; lack of awareness about the HIV support organizations available to them and how to access them; insufficient HIV-related knowledge56,60,77,78,84,85,97,100 Lack of education Lack of general education level and education about HIV/AIDS-related health and social systems in individuals61 Language issues Not fluent in host country language58,62,63,70,77,80,82,85,102 Mental health challenges Overwhelming sense of social isolation101 Navigation challenges New or unfamiliar health care system; confusion around service provision and the process of obtaining health insurance; appointment systems were intimidating for those unfamiliar with the system or with English as a second language58,63,65,68,77,80,95,97,101,102 Personal attitudes and traits Lack of willingness to seek care unless absolutely necessary; lack of confidence in American medicine; feelings of social exclusion, shame, self-loathing; fatalistic views about HIV65,77,78,86,97,112 Policy confusion Around care entitlement60,62,65,75,81,94,97,101 Stigma General feelings of stigma were found to impact access to care78 |

Lack of education Lack of general education level and education about HIV/AIDS-related health and social systems in family members61 Lack of social support Lack of people to turn to for assistance and guidance85 Stigma From families61 |

Inadequate clinical environment GP receptionists were associated with breaches of confidentiality; lack of HIV care-related information dissemination to patients by immigration medical exam panel physician; policy changes by the city that effect patient care provision have not been consistently taken up at health centres65,71,77,83,92,93 Lack of acknowledgment, awareness, and response to cultural diversity Difference in communication styles and cultures between migrant patients and US clinicians97 Language issues Lack of Spanish signage in hospitals makes navigation difficult63 Navigation challenges Lack of “front door” entry to HIV care and services for men; being referred between services without knowing what they were for65,85 Stigma By non-HIV health care professionals59 |

Distrust Community-based distrust with care providers and care systems61 Stigma From community settings61,65,101 |

Insufficient governmental social service support Lack of funding for social support services; lack of legal status led to work restrictions, lack of insurance, and difficulties meeting paperwork requirements which are necessary for entry into HIV care58,64,65,70,85,89 Language issues Forms for government services (for which migrant patients were eligible to apply to) were not available in Spanish63 |

| Retention | Competing priorities Housing, shelter, homelessness; unexpected travel duration extension; work commitments, employment, and finances; family, childcare; transportation; food; clothing and poverty; immigration, obtaining legal documents and insurance; rape, domestic violence, death and loss54,63,65,66,70,75,80,86,94,97,99–102,104–106,112 Disclosure and confidentiality issues Leeping HIV status confidential takes precedence over taking medication on time57,61,78,102,107,108 Distrust With treatment and care providers54,66,80,105,112 Fear Of side effects and long-term harm from care; deportation; disclosure; losing their job; incarceration; isolation; stigma56–58,60,61,63,65,66,68,70,77,78,82,95,97,102,105,112 Financial issues Inability to afford care and/or insurance copayments; travel costs lead to missing appointments; cost of taking time off to attend appointments61,62,68,76,80,82,111,112 Intensity and novelty of treatment adherence Meeting multiple medical appointments and adhering to rigorous medication regime was daunting and demanding; participants had to absorb lots of info and medical terminology84,85,106 Lack of education General education level of patient82,109 Lack of knowledge Lack of awareness and use of a policy to get legal status and benefits; insufficient HIV-related knowledge which affects care navigation60,77,82,84,97,105 Language issues Not fluent in host country language56,58,65,66,68,70,80,82,85,86,94,105 Medication consumption difficulties Drugs requiring dietary manipulation were difficult to manage for those with limited access to food or cooking facilities; number of pills that needed to be taken and side effects with treatment including as diarrhea, rash, lipodystrophy, pain and weakness62,72,73,80,105,106,112 Mental health challenges Trauma; depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, and substance use; feeling trapped, due to immigration status; negative internal dialogue54,86,95,100,102,106,112 Navigation challenges Appointment systems were intimidating for those unfamiliar with the system or with English as a second language; little ability to navigate through bureaucratic US systems58,65,95,97,102 |

Disclosure and confidentiality issues Undisclosed HIV status to parents, family members, and/or friends; difficulty concealing medicines when living in shared accommodations and need to avoid taking them in public; many would sacrifice care than have their status disclosed; several reported that if HIV status was accidently disclosed, they were fired from their jobs, ostracized, and/or evicted54,72,73,80,86,100 Lack of social support Lack of emotional and social support82,86 Stigma Discrimination, threats, physical abuse, and unfair treatment by family, friends due to HIV86 |

Disclosure and confidentiality issues Geographic area of community members in relationship to HIV services; use of interpreters from the same communities as clients97 Inadequate clinical environment Lack of space, capacity, funding, staff, and services; unprofessional staff; weak patient-physician relationship with GPs; dispensing medications in public; medications may not be available on the same day as scheduled appointments; distance to HIV clinician; insufficient or inappropriate translation services; poor coordination of services; highly fragmented system of care; inconsistent uptake policies at clinics56,61,65,66,68,70,73,77,78,80,82–85,90,92,93,100,102,105,112 Lack of acknowledgment, awareness, and response to cultural diversity Lack of understanding by clinic admin of Latinx cultural naming system; failure of clinicians to understand cultural factors, social exclusion, and poverty63,65,77,86,97,102 Lack of education Providers found it difficult to communicate effectively with patients that had little or no formal education77 Language issues Services provided in English; no comprehensive translation system exists56,66,68,77,86 Navigation challenges Being referred between services without knowing what they were for; patients had to go back-and-forth between various HIV specialist units58,65,85,90 Policy confusion Lack of clarity around changes in immigration policies and associated implications to public charge rules58 Stigma By non-HIV health care professionals; migrants denied right to care because of route of infection59,66,102 |

Distrust Community-based distrust with care providers and care systems61 Lack of acknowledgment, awareness, and response to cultural diversity Community-based acculturation, cultural factors—especially gender roles105 Stigma Propelled by the media; HIV phobia exists in Japan; migrants faced discrimination and/or dismissal when found taking medication at work65,66,86,97 |

Insufficient governmental social service support Social service provision is not sufficient; lack of health insurance due to immigration status57,58,64–66,70,75,77,82,85,89,98,110 Lack of acknowledgment, awareness, and response to cultural diversity Avoidance of responsibilities associated with foreigners by officials66 |

| Personal attitudes and traits Pride; lack of claiming rights because of status; lack of confidence in American medicine; asymptomatic HIV self-blame and shame; self-loathing; magical-religious beliefs; fatalistic views about HIV; denial57,61,66,77,80,82,86,88,97,105,111 Policy confusion Uncertainty regarding regulations and power ascribed to Immigration and Customs Enforcement; confusion around availability of the AIDS Drug Assistance Program to undocumented immigrants and around immigration policies58,60,85,94,105 Stigma Indirectly influences psychological well-being and social support; directly complicates adherence107,108 |

|||||

| Suppression | Financial issues Lack of finances and unemployment55 Lack of education In reference to general education level of patient55 Mental health challenges Several stressors including feelings of limbo, uselessness, shock, anxiety, panic, and depression; clinically significant depressive symptoms96,108 |

— | — | — | — |

ART, antiretroviral treatment; GP, general physician.

Barriers—linkage

Individual-level barriers

Fear was at the forefront of the individual-level barriers associated with linkage to care and initial treatment provision. Fear was most notably ascribed to deportation,56,60,61,63,66,70,75,78,82,86,95,97,100–102,105,112 consequences related to disclosure of HIV status (e.g., loss of job, social isolation, stigma, and incarceration),56,57,65,68,70,75,77,82,95,97,102,105 and negative effects from initiating treatment (i.e., potential side effects to health).57,78,105

Lack of proficiency in the host country's language among MLWH was the second most reported barrier impeding initial access to care and treatment at the individual level.56,58,62,63,65,66,68,70,77,80,82,85,86,94,102,105 Language seemed to amplify navigation-related challenges in particular.77,102 For example, physically navigating clinics and hospitals in North Carolina was made difficult due to lack of Spanish signage.63 Lack of language proficiency was also reported to hinder MLWH from applying to government services, for which they were eligible (e.g., documents only available in one language), possibly impeding their initial access to HIV care and treatment.63

Navigation-related challenges, such as not knowing the structure of the health care system, were a major hurdle for MLWH. Retained studies indicated that these populations often lacked knowledge and education about HIV care and services, and were often unfamiliar with the health care system and overarching culture in their host countries.58,60,68,77,78,80,84,85,97,101,102,105

Concerns, uncertainty, or lack of awareness regarding their eligibility for care as a result of their immigration and HIV status seemed to delay MLWH's entry into HIV care and treatment.58,60,62,65,75,81,94,100,101,105 In cases where MLWH could be eligible for subsidized or free HIV care and treatment, delays were potentially experienced by some due to lack of relevant documentation.70,77,110 For example, in some jurisdictions, proof of residence was required to receive free medical examinations. For some women, this was identified as a barrier to initial care, particularly when documentation was not under their own name.77

Interpersonal-level barriers

Lack of a social support system, which includes people who are aware of one's status, seemed to be an impediment to HIV care linkage.85 Loved ones and personal networks can provide important guidance and assistance post-HIV diagnosis. However, if key members of the network (e.g., family members) lack education or knowledge about HIV-related health and social systems, or worse, if these members harbor stigmatizing attitudes toward HIV, they can impede linkage to initial care and treatment.61

Organizational-level barriers

General practitioners (i.e., family physicians, primary care specialists) and immigration medical examination physicians were critical for linking MLWH to HIV care in several OECD countries. Stigma experienced by MLWH from these clinicians appeared to delay HIV care linkage.59,78,102 These practitioners were also seen as crucial for disseminating information on the nature, access, and reasons to seek HIV care and services. Failure to give MLWH sufficient or tailored information is likely to hinder linkage.71,85 In addition, one study reported that women could be linked to HIV care through pregnancy and childcare services, while men appeared to lack a comparable front door to care.65

Community-level barriers

Communities and their affiliated centers had the potential to facilitate MLWH linkage to HIV care and treatment. However, HIV-related stigma was reported to impede the development of effective community-based responses that impacted MLWH's initial linkage to care and treatment.61 This was exemplified in the context of a Haitian American community in Florida, USA, where the sense of humiliation, dehumanization, and alienation experienced by MLWH from community members extended into the church setting, which in turn prevented this traditional social system within the community from acting as a strong source of linkage for MLWH to professional care.61

Policy-level barriers

When policy changes that could improve MLWH's HIV care access were not taken up consistently across HIV care services, some MLWH were turned away from free medical examinations or prescription coverage.77,85,105 Immigration-related policies, such as a 3-month wait period to access insurance, and ineligibility to join national health insurance, also hindered some MLWH from initially accessing HIV care and treatment.64,66,85,89,98,110 For some MLWH, enrolling in clinical trials or importing generic drugs from overseas were the only way to obtain treatment, both of which were not ideal and could delay or impede treatment initiation.85

Barriers—retention

Individual-level barriers

Once linked to HIV care, MLWH faced several challenges that limited their ability to engage with care and treatment in the long-term. Competing priorities such as housing, food, financial and work commitments, familial responsibilities, obtaining legal status, addressing or improving mental health, and preserving confidentiality were often deemed more or as important as HIV care and treatment by MLWH.54,63,65,66,70,75,80,86,94,97,99–102,104–107,112 If these competing priorities were not adequately met, disengagement with care could result.

Particularly for undocumented MLWH, lack of legal status led to work restrictions and lack of employee benefits (e.g., paid leave), often making retention in care considerably difficult.70 Moreover, MLWH's fears when first accessing services and treatment in their host country were reported to persist in some undocumented MLWH, even after several years.70 MLWH's worry for losing their jobs and becoming socially isolated sometimes led to mismanagement of treatment (e.g., not taking medication on time due to people being around) or disengagement with care.66,107

Interpersonal-level barriers

Lack of a social support system and resulting feelings of isolation were reported to impede both linkage to and retention in care and treatment.80,82,86 Further, retention in care and treatment was negatively affected when MLWH experienced or perceived discrimination, threats, physical abuse, and unfair treatment due to their HIV status by family, friends, and community members.86

Organizational-level barriers

After individual-level barriers, an inadequate clinical environment appeared to be the largest threat to retention in HIV care and treatment.56,61,65,66,68,70,71,73,77,78,80,83–85,90,94,100,102,105,112 Several factors determined the inadequacy of a clinical environment for MLWH. Lack of space and capacity were associated with increased numbers of patients in clinics and thereby longer waiting times.56,65,73,78,94 This, in turn, seemed to propel fear of disclosure, which impacted decisions to attend appointments. In fact, any aspect of the clinical environment that could impact confidentiality seemed to be detrimental to appointment attendance.78 This included dispensing medications in public, dedicated wards for in-patients, and the use of interpreters and translators from the same community as the MLWH.78

A poor patient-physician relationship seemed to be the hallmark of poor retention.65,78,80,100 Feeling judged by health care providers, lack of perceived emotional support or consideration, and rigidity in the time allotted for consultations could engender loss-to-follow-up. Conversations around sexual health were taboo or uncomfortable for some MLWH and could diminish trust in clinicians.61,86,97 Further, discrimination experienced in the clinical environment threatened MLWH's willingness to engage with care.78,102 Apart from the patient-physician relationship, poor coordination and a highly fragmented health care system, in which HIV care and services are provided, were associated with loss-to-follow-up.90,102 Also, if medications were not available on the same day as scheduled appointments, treatment adherence could be affected.80

Unprofessional, stigmatizing, and undertrained clinical staff negatively impacted engagement.61,68,83 In particular, lack of acknowledgment, awareness, and response to cultural diversity by clinical staff translated into several challenges for MLWH.63,65,77 For instance, Latinx populations often use two last names (which can be hyphenated) and sometimes alternate between the use of these names.63 Unaware receptionists may not look for the appropriate name associated with the patient's file which, in turn, meant MLWH had to reschedule appointments for another date and thereby incur substantial economic loss (e.g., missed work and transportation costs).63 Situations like this could discourage MLWH from continuing to engage with care.

Lack of funding added to the plethora of issues with the clinical environment, by hindering planning, service stability, and the ability of clinics to hire more staff and develop initiatives to appropriately respond to the needs of MLWH.56,58,65

Community-level barriers

MLWH could face stigmatizing attitudes toward HIV by family, friends, community members, alongside the overall HIV phobia and antagonism related to immigration that exits in certain countries.65,66 Both stigma in relationship to HIV and immigration were discussed in the retained studies as an indirect negative influence on the psychological wellbeing of MLWH (i.e., internalized stigma, living in fear, lack of social support) and as directly impacting their willingness to engage with care and adhere to treatment.107,108

Policy-level barriers

Uncertainty about immigration status and possibility of deportation was reported as a possible reason to space medication-taking to save doses for the future,85 which could impact MLWH's medication management (i.e., properly following prescriptions). Moreover, antiretroviral treatment could be withdrawn if MLWH's appeal against immigration authorities to remain in their host country if seeking refuge or asylum was unsuccessful.85 In some OECD countries, social service support by the government to resolve or mitigate MLWH's competing needs (e.g., food, housing, finances) was provided (i.e., the United Kingdom), but was discussed in a few studies as not sufficient to address their challenges.57,58

Facilitators—key descriptive trends

Ten descriptive categories of facilitators were identified. These facilitator categories were reported a total of 75 times across the 59 retained studies. The most prevalent facilitator categories reported across the dataset were having: an adaptive clinical environment (25/59; 42%); sufficient social support (15/59; 25%); and positive personal attitudes and traits (12/59; 20%). Facilitators could be attributed to more than one level of the Socio-Ecological Model and step of the HCC. In the Socio-Ecological Model, most reported facilitators were associated with the organizational level (34/75; 45%), followed by the individual (18/75; 24%), interpersonal (16/75; 21%), policy (6/75; 8%), and community (1/75; 1%) levels. In the HCC, most reported facilitators seemed to influence retention (64/84; 76%), followed by linkage (15/84; 18%), and then achievement and maintenance of viral suppression (5/84; 6%). No significant pattern by country or year was identified. See Table 4 for a cross-map of facilitator categories with examples by Socio-Ecological Model level and step of the HCC.

Table 4.

Facilitator Categories with Examples Cross-Mapped to the Levels of the Socio-Ecological Model and Steps of the HIV Care Cascade

| Individual | Interpersonal | Organizational | Community | Policy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linkage | Appropriate acknowledgment, awareness, and response to cultural diversity General acculturation to American culture61 Sufficient education Higher levels of general education61 Sufficient finances Higher levels of socioeconomic status; those employed were covered by health insurance61 |

Sufficient social support From peers57 |

Appropriate acknowledgment, awareness, and response to cultural diversity Making immigrants feel explicitly welcome; training reception staff; posting signage; having protocols and referrals in place for clients; and staffing programs and clinics with individuals who spoke multiple languages and experienced immigration themselves58 Remarkable/Adaptive clinical environment Approachability, supportiveness, and availability of staff; staffing of Health Advisors; existence of non-HIV/AIDS specific services; the existence of a sector composed of hospital structures and humanitarian organizations that specializes in caring for the most vulnerable patients56,58,61,84,91,92,101 |

Appropriate acknowledgment, awareness, and response to cultural diversity Use of local Latinx newspapers and radio stations to identify potential HIV/AIDS services within their community63 |

Sufficient governmental social service support Universal Health Coverage and State Medical Assistance provides social protection for the entire population, including the poor and the undocumented since 200072,75,85,90,92,110,111 |

| Retention | Personal attitudes and traits Intrinsic motivation; perceived benefit of treatment; spiritual belief and religious faith; personal strength, accountability, self-reliance,57,72,73,80,81,86,95,96,100,105,106,112 Physiological variables and dispositions Older age; higher HIV viral load at enrolment; occurrence of an AIDS event before enrolment; pregnancy; hepatitis B virus coinfection104 Sufficient education Higher levels of general education103 |

Familial responsibility Both men and women described parenting responsibilities and avoidance of becoming a burden on family as motivations for staying healthy80,86,100 Mitigating issues of disclosure and confidentiality Avoiding disclosure issues by being single54 Sufficient social support From peers, partner, family, voluntary organizations, peer support groups56,57,72,78,80,86,87,100,105,106,112 |

Appropriate acknowledgment, awareness, and response to cultural diversity Providing language concordant services; hiring staff that were familiar with the immigration process; recognizing heterogeneity within immigrant communities; training for staff; culturally appropriate, gender specific, and integrated community-based interventions56,58,78,105 Remarkable/Adaptive clinical environment Assistance with conflicting individual needs such as housing, finances, and food; designated staff member to coordinate appointments and interpreters to overcome issues with appointment keeping; establishing medical-legal/public-private partnerships enabled direct response to immigrant patient needs; taking services directly to immigrants in both rural and urban settings; strong patient-physician relationship; supply ART directly to patients at the HIV/AIDS clinic; multidisciplinary teams56–58,61,67,72–74,77,79–81,84,86,92,95,96,100,105,106,109,112 Sufficient social support From HIV service organizations, consultation with faith leadership, and counseling services93,95,96 |

— | Sufficient governmental social service support Free or subsized health care and treatment coupled with provision of social support72,75,85,90,99,110 |

| Suppression | — | Mitigating issues of disclosure and confidentiality Disclosure to mother or friends55 Physiological variables and dispositions Being a woman was related to higher T CD4+ lymphocyte count and a lower viral load69 Sufficient social support Perceived informal support69 |

Remarkable/Adaptive clinical environment Interventions that enable free provision of ART and directly to patients in the clinic were essential to establishing suppression74,98 |

— | — |

Facilitators—linkage and retention

Individual-level facilitators

Having intrinsic motivation, self-reliance, or resilience greatly increased the likelihood that MLWH were initially linked to and retained in care and treatment.57,72,73,80,81,100,106,112 Belief in the value of treatment increased the extent to which MLWH engaged with care and treatment.80,81,96 For MLWH who were able to access HIV treatment in their host country, willingness to adhere to their regimens seemed bolstered by an understanding that HIV treatment for many in their country of origin was inaccessible, unaffordable, and very limited.96,100 Higher levels of education and socioeconomic status were identified in the retained studies as facilitators to linkage and retention (e.g., employed individuals may have access to health insurance).61,103 Spiritual beliefs and religious faith were also found to be important for some MLWH as this could offer a source of hope and optimism that fostered resilience after HIV diagnosis, strengthening commitment to HIV care and treatment.57,80,86,95

Interpersonal-level facilitators

Informal social support provided by friends, family, partners, and peers, as well as formal social support provided by peer support groups, HIV service organizations, faith leaders, and counseling services were identified as important for MLWH.56,57,69,72,78,80,86,87,93,95,96,100,105,106,112 Negative consequences of stigma could be buffered when MLWH had social support systems in place.100 In addition, having a support system was identified as giving meaning to life, which in turn was reported as facilitating and encouraging willingness to remain engaged in HIV care, especially in periods of low intrinsic motivation.86 Being a parent motivated both male and female MLWH to remain healthy so as to fulfil their responsibilities and avoid becoming a burden on their family.86,100 Members of the social support team for MLWH could provide emotional support and remind them of their appointments and medications, all of which encouraged appointment attendance and treatment adherence.80,86,106,112 These individuals could act as doctors' allies by listening to and reciting doctor recommendations if they joined MLWH in their medical appointments.80

Organizational-level facilitators

The clinical environment played one of the most important roles in linking MLWH to and retaining them in HIV care and treatment.56–58,61,67,72–74,77,79–81,84,86,91,92,95,96,98,100,101,105,106,109,112 The backbone of an excellent clinical environment seemed to be strong patient-physician relationships.72,73,80,86,100,106 For MLWH, good relationships included efficient communication, attention, a caring attitude, compassion, trust, flexibility with scheduling appointments, provision of psychological support, giving results over the phone, and knowledge-sharing.72,73,80,86,100,105,106 However, the clinical environment's significance was not limited to the primary attending clinician, but extended to the entire clinical team, including the staff.56,77,96,105 In fact, the availability and approachability of staff was deemed important to MLWH.56,96,105

Further, having a designated staff member to coordinate appointments was reported to improve MLWH's appointment attendance.56 A multidisciplinary team including nurses, community health workers, case managers, social workers, or health advisors facilitated continuity of care for MLWH and helped address several barriers.56,77,79,81,84,86,95,96,100,101,112 For instance, team members in some jurisdictions found ways to obtain care for MLWH without health insurance.56,77,81 They also resolved critical needs such as those related to housing, acquiring health insurance, receiving food assistance, and accompaniment of MLWH to clinical or legal appointments.56,79,95,100,101

Interventions that enabled clinics to dispense antiretroviral medication directly to patients in-clinic saw decreases in loss-to-follow-up among MLWH and overall better adherence to treatment.74 Taking services directly to MLWH in rural and urban settings also facilitated linkage to care, particularly when fear of obtaining care was heightened for MLWH as a result of the 2016 elections in the United States.58 In addition, establishing medical-legal partnerships enabled a direct response to immigration needs.58,67,79 These partnerships between clinics and legal offices improved the medical teams' understanding of immigration policy, facilitated the development of procedures to guide the team's interactions with immigration authorities, and linked MLWH with relevant legal services.58,67,79

Establishing a clinical environment with an inclusive approach to address cultural diversity also appeared crucial to linking MLWH with HIV care and encouraging their sustained engagement.56,58,63,78,105 Training staff increased their awareness of the challenges MLWH face, and thereby their empathy.56 Providing language-concordant services (i.e., offering services in multiple languages), hiring multilingual staff familiar with the immigration process, understanding the heterogeneity within MLWH populations, posting tailored signage, and having protocols and referrals in place for MLWH were also instrumental in establishing a supportive and accepting environment for MLWH.56,58,105

Community-level facilitators

Very few facilitators at the community level were identified. One study mentioned MLWH use of local Latinx newspapers and radio stations to identify potential HIV/AIDS services within their community, which may have facilitated their linkage to HIV care and services.63 In two other studies, the importance of having integrated community-based interventions or services was highlighted, which may have facilitated MLWH's retention in HIV care and treatment.78,101

Policy-level facilitators

Policies around universal health coverage differed across OECD countries. Health policies and systems that enabled compassionate HIV care and treatment provision for MLWH seemed to facilitate linkage.72,75,85,90,92,110,111 In this respect, Sweden and France particularly stood out. For example, in Sweden, efforts have been made to establish equitable health systems for all: “the Swedish Health and Medical Services Act mandates that all citizens and residents in Sweden should have equal access to health care regardless of gender, socioeconomic status, geographical region of residence, or national, ethnic, cultural, religious, and linguistic background.”90 In France, however, efforts have been made to enable access to care for documented and undocumented foreign-born residents through their combined Universal Health Insurance Coverage and State Medical Assistance systems.110

Discussion

This SMSR synthesized the results from 59 studies and identified many barriers and facilitators related to HIV care and treatment, as experienced by MLWH in OECD countries. Drawing on both the HCC and the Socio-Ecological Model, this review is the first to conduct a multilevel analysis of the complex factors that affect MLWH across 17 OECD countries.

This review highlights that most reported barriers are associated with retention in care (i.e., long-term engagement with HIV care) and treatment adherence (i.e., long-term adherence to medication as prescribed), and not with linkage to care and treatment initiation or the achievement of viral suppression. In fact, 68% of reported barriers centered on retention compared to 30% on linkage. In addition, almost two-thirds of these barriers focused on the individual level (64%). In fact, a crucial finding of this review was the considerable impediment unmet or unfulfilled basic needs (e.g., housing, food security, financial stability, work commitments, and mental health) can be to MLWH. If these patients are linked to care and treatment but their “competing priorities” are not addressed, disengagement is likely.

In comparison, a key facilitator identified in this review was establishing multidisciplinary teams for HIV care in clinical settings, as this enabled the hiring of designated clinicians and staff to ensure that MLWH's essential needs were met. Social workers and clinical staff with similar training were particularly adept at facilitating access to compassionate care for MLWH despite differences in legal status, while also helping these patients secure housing, food, financial, and psychological support. These results highlight the great potential of multidisciplinary teams to resolve competing issues faced by MLWH, and thereby improve their long-term engagement with HIV care and treatment. As such, HIV-related care settings, and especially primary HIV care clinics, should consider adopting multidisciplinary models with sufficient funding for a social worker or clinical staff member with similar training and expertise. This can be done in conjunction with the adoption of other existing evidence-based interventions that improve HIV care engagement and treatment adherence, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Anti-Retroviral Treatment and Access to Services intervention,113 or the Retention through Enhanced Personal Contacts intervention as presented by Gardner et al.114—although these would require tailoring and piloting to ensure that they are sufficiently adapted to the needs of MLWH.

A note on achieving viral suppression

Very few barriers and facilitators directly related to achieving viral suppression were identified. This is understandable as final or downstream steps in the HCC are impacted by factors associated with upstream care steps. However, this finding may also indicate that much work remains to be done at the levels of linkage, retention, and reengagement for MLWH globally (e.g., for those who have been lost to follow-up or dropped out of care). In addition, this may point to the need to better understand bidirectional movements along the steps of the HCC (e.g., managing loss-to-follow-up of MLWH due to further migration). In this respect, future scholars may want to consider utilizing the HCC framework established by Kay et al.,29 which highlights these dynamic movements along the spectrum of HIV care engagement, or the revised HCC framework presented by Ehrenkranz et al,115 which explicitly integrates the idea of disengagement and reengagement with HIV care.

Intersectionality and paths for future research

Many of the barriers identified in this review, particularly those related to the individual-level of the Socio-Ecological Model (e.g., fear, lack of host-language proficiency, and care navigation-related challenges) have been previously reported as commonly experienced by international migrant populations living in OECD countries.116–122 However, several included studies showed how complex identity dynamics experienced by MLWH (e.g., based on their immigration or HIV status, gender, and racial or ethnic backgrounds) magnified barriers. For example, experiences and perceptions of stigma based on one's HIV and migrant statuses were reported to amplify MLWH's perceived vulnerability when accessing care and treatment. Intersectionality theory, which posits that people generally experience discrimination and oppression uniquely and that consideration should be given to all potential contributors to their marginalization or vulnerability, may be useful to future, more granular, analyses of these issues. Importantly, the viability of this theory has previously been explored in scholarly articles.123,124

The COVID-19 pandemic

Since the implementation of our search strategy (March 25, 2020), the COVID-19 pandemic has taken an unprecedented toll on society. The effects of COVID-19 have penetrated HIV care and have affected MLWH in diverse ways.125–128 Economic disruptions, social and physical isolation, vaccine and care access hesitancy, overburdened health systems, shifts in clinical and funding priorities from HIV care to COVID-19, among many other challenges, have fed into the impact the pandemic has had (and continues to have) on MLWH. Future studies should thoroughly explore the challenges faced by MLWH during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, we posit that adapting the clinical environment to host a multidisciplinary team with a designated community health worker, case manager, social worker, or health advisor would help address the needs of MLWH and facilitate their sustained engagement in care amidst the pandemic and future instances of lockdown and social distancing measures.

Strengths and limitations

The comparability of the data and the generalizability of interpretations were complicated by variation across OECD countries in the legal definition and descriptions of categories or statuses of migrants and in their health care eligibility (i.e., existence of specific health insurance or care provision policies). They were also complicated by the overall heterogeneity of the migrant populations studied. Further, retained studies lacked consistent reporting of data in relationship to the age range, age at migration, and years living in the receiving country for each sample of MLWH. Nevertheless, comparing data from OECD countries can generate a comprehensive understanding of health system performance that can help guide and promote the development of evidence-based international standards for a range of social and economic challenges.129–131 Use of the SMSR methodology, which enables the amalgamation and analysis of data from various study designs, alongside qualitative content analysis was key to mitigating this limitation. The qualitative analysis also indicated that despite the heterogeneity of the data sources, the reported barriers and facilitators faced by MLWH proved similar regardless of their ethnic and geographic origins, host country, sex or gender, and legal status.

As this is a systematic review, results are necessarily secondary in nature (i.e., developed based on findings from other scholars) and may reflect research interests (e.g., retention issues) in the scholarly community. However, rigorous analytical techniques (i.e., qualitative content analysis) and careful interpretation of data using established frameworks (i.e., the HCC) and models (i.e., the Socio-Ecological model), nuanced by the engagement of patient-partners, helps address this limitation, in part.

A final limitation to note is that only studies published in English were retained beyond the full-text screening phase. OECD countries have a diversity of official languages, and therefore, non-English speaking countries may be underrepresented in the dataset. Twenty-eight studies were excluded on the basis of language during the full-text review phase. However, the dataset does include studies from 17 OECD countries, with the majority (n = 12) not having English as their primary official language.

In conclusion, this is the first review to report a multilevel analysis of barriers and facilitators that impact MLWH in OECD countries with respect to linkage and retention in HIV care and treatment. While linking MLWH to care is challenging, the problem of long-term engagement in HIV care and treatment seems to have received the most attention. Addressing policy-related barriers may improve initial linkage to HIV care and treatment. However, adapting clinical environments to better address the complex individual needs and concerns of MLWH with multidisciplinary care models and sufficient funding for social workers or clinical staff with similar training offers a promising strategy to attenuate and potentially resolve care retention issues across OECD countries.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Taline Ekmekjian for her support as an academic librarian. She assisted with the revision of our eligibility criteria and the development of the search strategy.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Antiviral Speed Access Program (ASAP) Migrant Advisory Committee

Authors' Contributions

This study was conceived by A.K.A., A.Q.-V., D.L., K.K.V.M., K.E., and B.L. The migrant patient advisory committee, collectively assigned as an author, was also involved in the designing of this work. A.K.A. worked with an academic librarian to establish the search strategy and eligibility criteria. The search strategy, eligibility criteria and study design were further revised in consultation with A.Q.-V., D.L., K.K.V.M., K.E., I.V., B.L., and the migrant patient advisory committee. A.K.A., D.L., K.K.V.M., and A.R.-C. were involved in the title and abstract screening. A.K.A. and D.O.-P. conducted the full-text screening, critical appraisal, and qualitative content analysis. A.K.A. conducted the thematic analysis. A.Q.-V., D.L., A.R.-C., K.E., the migrant patient advisory committee, and B.L. were involved in the data interpretation and analysis phase. A.K.A. wrote several versions of this article. All authors have provided substantial edits to multiple versions of this article. All authors provided their final approval for the publication of this version of the article and agree to be accountable for all aspects of this work.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Funding Information

A.K.A. was supported by a doctoral scholarship from the Fonds de Recherche Québec—Santé (FRQ-S) given in partnership with the Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) Support Unit of Quebec. A.K.A. is supported by a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship given through the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. B.L. is holder of a Canadian Institute of Health Research, Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (CIHR/SPOR) Mentorship Chair in Innovative Clinical Trials for HIV Care. B.L. holds a grant funded by Gilead Investigator Sponsored Research Program, which partially funded A.K.A.'s doctoral studies. B.L. is also supported by a career award LE 250 from the Quebec's Ministry of Health for researchers in Family Medicine. B.L. also reports grants for investigator-initiated studies from ViiV Healthcare, Merck, and Gilead; consulting fees from ViiV Healthcare, Merck, and Gilead (with funding information). N.K. is supported by a career award from the FRQ-S (Junior 1).

References

- 1.International Organization for Migration. World Migration Report 2020. United Nations Migration, 2020. Available at: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/wmr_2020.pdf (Last accessed April21, 2021)

- 2.Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. International Migration 2019: Wall Chart. United Nations;. 2019. Available at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/files/documents/2020/Feb/un_2019_internationalmigration_wallchart.pdf (Last accessed April21, 2021).

- 3.The World Bank. The World by Income. Atlas of Sustainable Development Goals. 2018. Available at: https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/images/figures-png/world-by-income-sdg-atlas-2018.pdf (Last accessed April21, 2021).

- 4.Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Where: Global Reach. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/about/members-and-partners/ (Last accessed April21, 2021)

- 5.Haddad N, Robert A, Weeks A, Popovic N, Siu W, Archibald C. HIV: HIV in Canada—Surveillance report, 2018. Canada Commun Dis Rep 2019;45:304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sullivan PS, Jones JS, Baral SD. The global north: HIV epidemiology in high-income countries. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2014;9:199–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross J, Cunningham CO, Hanna DB. HIV outcomes among migrants from low-and middle-income countries living in high-income countries: A review of recent evidence. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2018;31:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tavares AM, Fronteira I, Couto I, et al. HIV and tuberculosis co-infection among migrants in Europe: A systematic review on the prevalence, incidence and mortality. PLoS One 2017;12:e0185526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tavares AM, Pingarilho M, Batista J, et al. HIV and tuberculosis co-infection among migrants in Portugal: A brief study on their sociodemographic, clinical, and genomic characteristics. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2021;37:34–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weine SM, Kashuba AB. Labor migration and HIV risk: A systematic review of the literature. AIDS Behav 2012;16:1605–1621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanser F, Bärnighausen T, Vandormael A, Dobra A. HIV treatment cascade in migrants and mobile populations. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2015;10:430–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reyes-Uruena J, Campbell C, Hernando C, et al. Differences between migrants and Spanish-born population through the HIV care cascade, Catalonia: An analysis using multiple data sources. Epidemiol Infect 2017;145:1670–1681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.UNAIDS. Seizing the Moment: Tackling Entrenched Inequalities to End Epidemics. Global AIDS Update. Geneva: UNAIDS, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blondell SJ, Kitter B, Griffin MP, Durham J. Barriers and facilitators to HIV testing in migrants in high-income countries: A systematic review. AIDS Behav 2015;19:20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alvarez-del Arco D, Monge S, Azcoaga A, et al. HIV testing and counselling for migrant populations living in high-income countries: A systematic review. Eur J Public Health 2013;23:1039–1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pottie K, Lotfi T, Kilzar L, et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of screening for HIV in migrants in the EU/EEA: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rade DA, Crawford G, Lobo R, Gray C, Brown G. Sexual health help-seeking behavior among migrants from sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia living in high income countries: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aung E, Blondell SJ, Durham J. Interventions for increasing HIV testing uptake in migrants: A systematic review of evidence. AIDS Behav 2017;21:2844–2859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keygnaert I, Guieu A, Ooms G, Vettenburg N, Temmerman M, Roelens K. Sexual and reproductive health of migrants: Does the EU care?. Health Policy 2014;114:215–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dias S, Gama A, Severo M, Barros H. Factors associated with HIV testing among immigrants in Portugal. Int J Public Health 2011;56:559–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoyos J, Fernández-Balbuena S, de la Fuente L, et al. Never tested for HIV in Latin-American migrants and Spaniards: Prevalence and perceived barriers. J Int AIDS Soc 2013;16:18560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ojikutu B, Nnaji C, Sithole J, et al. All black people are not alike: Differences in HIV testing patterns, knowledge, and experience of stigma between US-born and non–US-born blacks in Massachusetts. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2013;27:45–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manirankunda L, Loos J, Alou TA, Colebunders R, Nöstlinger C. “It's better not to know”: Perceived barriers to HIV voluntary counseling and testing among sub-Saharan African migrants in Belgium. AIDS Educ Prev 2009;21:582–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amibor P, Ogunrotifa AB. Unravelling barriers to accessing HIV prevention services experienced by African and Caribbean communities in Canada: Lessons from Toronto. Glob J Health Sci 2012;4:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kronfli N, Linthwaite B, Sheehan N, et al. Delayed linkage to HIV care among asylum seekers in Quebec, Canada. BMC Public Health 2019;19:1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Understanding the HIV Care Continuum. CDC; 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/factsheets/cdc-hiv-care-continuum.pdf (Last accessed April21, 2021).

- 27.Minority HIV/AIDS Fund. What Is the HIV Care Continuum? The US Government; 2020. Available at: https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/policies-issues/hiv-aids-care-continuum (Last accessed April21, 2021).

- 28.Wilton J, Broeckaert L. The HIV treatment cascade—Patching the leaks to improve HIV prevention. CATIEP: Canada's source for HIV and hepatitis C information;. 2013. Available at: https://www.catie.ca/en/pif/spring-2013/hiv-treatment-cascade-patching-leaks-improve-hiv-prevention (Last accessed April21, 2021).