Abstract

Although advance care planning (ACP) is highly relevant for nursing home residents, its uptake in nursing homes is low. To meet the need for context-specific ACP tools to support nursing home staff in conducting ACP conversations, we developed the ACP+intervention. At its core, we designed three ACP tools to aid care staff in discussing and documenting nursing home resident’s wishes and preferences for future treatment and care: (1) an extensive ACP conversation guide, (2) a one-page conversation tool and (3) an ACP document to record outcomes of conversations. These nursing home-specific ACP tools aim to avoid a purely document-driven or ‘tick-box’ approach to the ACP process and to involve residents, including those living with dementia according to their capacity, their families and healthcare professionals.

Keywords: communication, education and training, nursing Home care

Key messages.

What was already known?

Uptake of advance care planning (ACP) is low in nursing homes; important barriers are insufficient knowledge and skills of care staff.

What are the new findings?

Newly developed ACP tools.

What is their significance?

Clinical: involve residents, their families and professionals in the ACP process while avoiding a ‘tick-box’ approach.

Research: fill the gap of detailed descriptions of ACP tools for nursing homes.

Advance care planning (ACP) is ‘a process that supports adults at any age or stage of health in understanding and sharing their personal values, life goals, and preferences regarding future medical care’.1 It usually involves several conversations with a person, family and healthcare professionals and can include appointing a legal representative.2 Moreover, specific preferences can be formalised by completing legal documents such as advance directives (ADs).

Nursing home residents are among the most frail populations3–7 and in the light of anticipated deterioration, discussing future care wishes and preferences is highly relevant. Nevertheless, the uptake of ACP in nursing homes seems low,8 9 with insufficient knowledge and skills of the care staff being one of the main reported barriers.10 11 Especially for nursing homes, where different care staff (ie, nurses, care assistants, allied health staff) can be involved in ACP,12 a clear need for context-specific ACP tools guiding ACP conversations has been reported.

To support the care staff in nursing homes to engage in ACP, we developed specific tools as part of a multicomponent ACP intervention, called the ACP+intervention.13 The goal of this intervention was to support the implementation of ACP as part of the routine nursing home practice in Flanders, the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium, using an 8-month stepwise educational intervention.14 We developed three ACP+tools to aid the care staff in eliciting, discussing and documenting the residents’ wishes and preferences for future treatment and care: (1) an ACP conversation guide, (2) a conversation tool and (3) an ACP document.

Given that recent reviews have found great variance in the content of different ACP tools and highlighted that detailed descriptions of intervention tools are often lacking,15 16 this report outlines the development and structure of the nursing-home specific ACP+tools. The ACP+tools aim to avoid a purely document-driven or ‘tick-box’ approach and, to involve residents, including those with dementia according to their capacity, their families and healthcare professionals in the ACP process.

Development of the ACP+tools

In the first stage, we conducted a targeted, systematic literature review of international research17 18 to explore existing ACP tools (eg, training manuals, information leaflets, conversation guide, documents) used in older populations and nursing homes.13 The following tools were examined further for common themes: ACP tools from a European ACP trial,19 the ACP document of University Hospital Leuven,20 the ‘Looking and thinking ahead document’ of a European palliative care trial (PACE EUFP7,21 the Advance Care Plan of Respecting Patient Choices,22 the ACP guideline no. 12 of the Royal College of Physicians of London, UK (2009)23 and existing practice guidelines for ACP in Belgium (published by pallialine.be, the organisation producing palliative care evidence-based guidelines under the Flemish Federation of Palliative Care).24 25

Together with a multidisciplinary expert group (consisting of an ethicist, three psychologists, a general practitioner, a sociologist and a social worker: CG, AW-vD, LP, LVdB, RVS, LD, JG, respectively), core themes for ACP conversations in nursing homes were selected, resulting in—among others—the ACP+conversation guide and the ACP+document. The preliminary tools were further reviewed by a legal expert and a palliative care nurse-trainer (LVH). All tools were tested in a feasibility study, involving two individual and three group-interviews with 17 management and staff members from five nursing homes.13 Participants expressed the need for a user-friendly and practical summary of the ACP conversation guide to use during ACP conversations.13 We therefore developed an additional one-page ACP+conversation tool with prompts that could be used throughout the ACP conversation.

Structure and content of the ACP+tools

Tool 1: the ACP+conversation guide

The ACP+conversation guide is a booklet including four chapters: (1) general information about ACP; (2) ACP conversations; (3) documentation of ACP outcomes, including how to draft an AD within the legal context of Belgium and (4) ACP with people with dementia and their families. An English translation of this guide can be found in the online supplemental appendix 1e.

bmjspcare-2021-003008supp001.pdf (1.2MB, pdf)

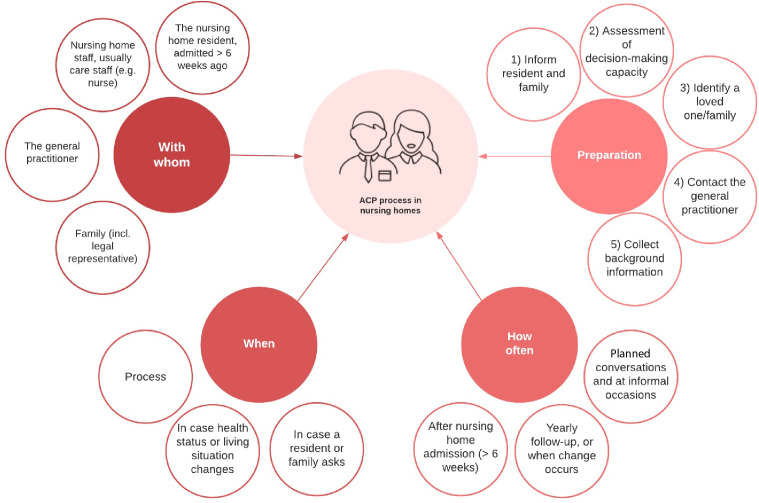

In the first chapter, general information about ACP is given: with whom, when, how often and which preparatory tasks are needed (figure 1). For example, an estimation of the decision-making capacity of the resident is advised. This chapter also highlights the importance of recognising that ACP is a process rather than a one-time event, that multiple conversations with the resident/family might be necessary and that preferences can be revisited regularly. It stresses that spontaneous conversations can occur but that planning conversations with all residents is important too.

Figure 1.

ACP process as outlined in the ACP+conversation guide. ACP, advance care planning.

The second chapter includes a template and communication tips to facilitate ACP conversations, comprising nine different sections, starting from broadly discussing what a good life entails for the resident and moving to more specific subjects about their preferences for future care, end-of-life care, death and dying. The order of the sections can be tailored to the residents’/families’ preferences and readiness to engage in ACP. Not all sections need to be addressed in one conversation. Moreover, the care staff is encouraged to actively listen to residents (eg, leave ample time for the residents/families to express themselves), and avoid having overly structured ‘Q&A’ conversations.

The third chapter provides information about how to document the outcomes of an ACP conversation using the ACP+document (described below). Additionally, this chapter explains how to use the official (legal) documents to appoint a legal representative and to create ADs,26 if the resident wishes to do so.

In the fourth chapter, the care staff is offered advice on conducting ACP conversations with residents with dementia. In summary, we recommended to (1) prepare well and provide relevant information on dementia to the resident/family; (2) customise the conversation to the level of the resident with dementia; (3) draw the attention of the resident with dementia regularly by saying his/her name or with a gentle touch; (4) use supporting materials such as pictures to back up verbal communication; (5) involve all important parties (eg, family) as early and as often as possible and (6) observe the interaction between the resident with dementia and his/her family, as well as the interaction between the different family members.

Tool 2: the ACP+conversation tool

The ACP+conversation tool (table 1) is an easy-to-use one-page document that is structured according to the nine sections of the second chapter of the ACP+conversation guide. It includes prompts which the staff can use to conduct an ACP conversation, to summarise it and to plan a follow-up ACP conversation (if applicable). Last, it summarises how and where the outcomes of the ACP conversation can be documented. This conversation tool helps the staff to guide conversations in a natural way and prevents forcing conversations into ‘tick box exercises’.

Table 1.

Approach of ACP conversation as outlined in the ACP+conversation guide

| The ACP+conversation tool | |||

| Add sentences that are convenient for you | |||

| Sections A and B | Sections C and D | Sections E, F, G, H and I | Summarise, document and follow-up |

|

Section A: Ideas about a good life (broadly asking about values) ‘What is important to you?’ ‘Which things make you feel joy?’ ‘What are you proud of?’ ‘What makes life worth living?’ ‘Do you think you have had a good life?’ ‘What do I need to know about you to give you the best possible care?’ ‘How could we improve your care?’ ‘Which things give you strength?’ ‘Do you have cultural, religious or spiritual beliefs? Would you like to talk about this with someone?’ ‘At which point do you consider life not to be worth living anymore?’ ‘What would you like your family, children and grandchildren to remember about you?’ ‘What would you like to finish in your life?’ ‘To which things would you still like to dedicate some time and energy?’ ‘Is there something you are strongly looking forward to?’ ‘Could you summarise for me what the doctors told you about your current health status?’ ‘What do you expect to happen to you?’ ‘What makes you happy? What is essential for your quality of life?’ ‘Is there any business that you would like to finish?’ Section B: Preferences for current care and treatment ‘How do you consider your current quality of life?’ ‘Do you currently have a good life?’ ‘How do you cope with your dementia/getting older?’ ‘What is the hardest part for you about living with dementia?’ ‘Do you find it hard to get older?’ ‘What does ageing mean to you?’ |

Section C: Preferences for future care and care goals Ideas and worries about the future and the end of life ‘When considering the future, what do you hope for/ are you worried about?’ ‘When considering your illness, what would be the best or worst thing that could happen to you?’ ‘Are you afraid to die?’ ‘Did you ever witness someone getting very ill, becoming dependent, or dying?’ ‘Did you ever witness someone else’s death, good or bad? How did you experience this?’ ‘Is there something you are afraid of? What would you rather avoid?’ The importance of ACP ‘Have you ever considered the medical care you would like to receive when you are too ill to decide on this? That is the goal of ACP, to guarantee you that you are cared for according to your wishes, even when you cannot convey these anymore.’ Common goals of care ‘Your health status could change in the future. Sometimes people can adjust or get used to this new situation, but not always. In the past you have told me that (eg, not being hospitalised…) was important to you. Is this still the case?’ ‘Would you like to consider your future health?’ ‘Is it important to you to make your own decisions? If so, what are the things you would like to decide about?’ ‘What is more important to you: suffering as little as possible/focusing on quality of life or living as long as possible?’ Section D: Appointing a legal representative ‘In case you would become so ill, you could no longer make decision about you care for yourself, is there someone you trust enough to make these decisions for you?’ ‘Would you like to appoint a legal representative?’ |

Section E: Documenting end-of-life wishes Advance directives ‘There are several ways to document your wishes. Some people think it is useful to compose an Advance Directive. You don’t have to do this if you don’t want to, and you should certainly not rush into this. Shall we discuss all the options together?’ ‘Have you ever heard about palliative care? What is your experience with this?’ ‘Would you still like to go to the hospital if you are in a critical state?’ ‘Do you have an Advance Directive? Would you like to compose an Advance Directive?’ In case of questions posed by resident or family about euthanasia*: ‘What does euthanasia mean to you?’ Preference with regard to resuscitation ‘There is a chance that you suddenly experience cardiac arrest, if this happens we can resuscitate you. Are you familiar with this? Have you ever thought about if you would want this?’ ‘Would you like to be resuscitated?’ Section F: Place of care/death ‘Where would you like to be cared for at the end of life?’ Section G: Other preferences ‘Are there other preferences you would like to take us into account?’ Section H: Preferences with regard to dying ‘Are there specific (religious) wishes that we should consider?’ ‘Would you like to make funeral arrangements?’ Section I: Revising preferences and wishes ‘Which circumstances would be a reason for you to revise your wishes and preferences about the care?’’ |

Summarise the conversation ‘So today you told me about… Is that correct?’ ‘Do I understand correctly that today we decide on the following…?’ Document wishes and preferences

Planning a follow-up conversation (if wanted) ‘A while ago we spoke about… You told me about… Is this still applicable?’ ‘A year ago, we spoke about … I was just wondering how you feel about this now. Would that be alright for you to discuss this?’ Communication to other involved healthcare professionals

|

*Euthanasia is a legal option in Flanders for people with decision-making capacity. This particular question should be considered in the light of this legal framework.

ACP, advance care planning.

Tool 3: the ACP+document and summary

The ACP+document (online supplemental appendix 2e) is meant to be filled in after an ACP conversation. It is structured according to the nine sections of the ACP+conversation guide and conversation tool. For each section, the care staff can write down what was discussed and which decisions, if any, were taken. Space is reserved to note who was present during the conversation, and to write down the observations of the care staff on the decision-making capacity of the resident.

Attached to the ACP+document is the ACP+summary, in which the care staff can highlight the most important decisions, that is, who is appointed as the legal representative and which ADs were composed by the resident. It is advised to keep the official (legal) ADs forms together with this summary in case of an emergency or a transfer to another care setting.

Discussion

There is a worldwide call to create opportunities for ACP conversations among nursing home residents, discussing ACP over several sessions and revising decisions made.27 In this paper, we discuss three tools that can be used to aid the nursing home care staff in discussing and documenting the resident’s wishes and preferences for future treatment and care. These tools are part of the ACP+intervention which aimed to support nursing homes with the implementation of ACP as part of the routine nursing home practice in Flanders, Belgium.28 The ACP+intervention is a training programme, set up to be implemented stepwise over a period of 8 months. It follows a train-the-trainer model, with the trainer’s support being intensive in the beginning, but decreasing throughout the process as nursing home staff become more autonomous in organising ACP (conversations) and consolidating the ACP+intervention.13 In the training sessions, care staff is trained in initiating and conduction ACP conversations, as well as in general communication skills, in addition to using the ACP+conversation tools. Training sessions that are specifically focused on performing ACP conversations entailed at least two sessions of 4 hours each and included among others, example cases and role play techniques. Moreover, on-the-job learning opportunities and management buy-in to support staff and create a safe learning climate are essential aspects of the intervention.13 17 29 Other key elements are described elsewhere.13

This paper serves as an important first step to provide practice with detailed tools to conduct both planned and spontaneous ACP conversations with the vulnerable nursing home population and their families. Our tools are consistent with best practices for discussing care goals, as was outlined by Bernacki et al 30 identifying a structured format to guide discussions and record information to hold promise in optimising ACP conversations.30 It should be noted that the ACP process is an ongoing process of communication rather than an on-off event31 and can therefore be time consuming,32 and that general practitioners (GPs) are not always available or willing to be engaged in this process.33 34 However, during the development phase of the ACP+intervention and the ACP+tools, the importance of considering ACP as a process and involving the GP, was stressed by healthcare professionals and experts.13 17 35

The absence of detailed intervention descriptions is a generally acknowledged phenomenon.15 When developing the ACP+tools, we therefore might have missed details of existing interventions or conversation guides, or tools described in the grey literature that might not have been covered by our search, but play an important role in daily nursing home care. However, two systematic literature reviews on ACP tools have been included in our search.17 18 Another limitation is that no nursing home residents or family were involved in the development of the ACP+tools; hence, their perspective is underexposed. However, in the developmental work of the ACP+intervention, two representatives of the council for older people in Flanders, Belgium were involved in the stakeholder panels. This process has been described elsewhere.35 Future work should further evaluate the use of the tools from a resident and family perspective.

While the local legal context influences which advance end-of-life decisions people can make (eg, euthanasia is a legal option in Belgium, but not in several other countries), the contextual barriers experienced by the nursing home staff to conduct ACP conversations are very similar across countries36 (eg, nursing home staff’s lack of confidence to engage in ACP,37 making the ACP+tools widely applicable). However, integrating the residents’ views and preferences in clinical practice, and ultimately aligning the residents’ preferences and care, requires active and systematic integration of ACP conversations into the clinical care structures and processes, next to time and labour.

Acknowledgments

The research team would like to thank the nursing homes in which we tested all ACP+related tools and procedures and Professor Herman Nys (KU Leuven) for the advice concerning Belgian medical law.

Footnotes

Twitter: @JoniGilissen

Contributors: Study conception: LVdB, LP, JG, AW-vD, LD, RVS, CG. Development of the tools: all authors. Drafting of manuscript: AW-vD, JG, LP, LVdB. Revising manuscript critically for important intellectual content: all authors. Final approval of the version to be published: all authors. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. LP and LVdB share last authorship.

Funding: The study was funded by the Research Foundation-Flanders (FWO) and the Interdisciplinary Network for Dementia Using Current Technology (INDUCT, EU Horizon 2020). LP was a Postdoctoral Fellow of the Research Foundation-Flanders (FWO, 2017–2020). JG is a postdoctoral fellow of the Belgian-American Educational Foundation (BAEF).

Disclaimer: The funders have no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in writing the manuscript or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:821–32. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piers R, Albers G, Gilissen J, et al. Advance care planning in dementia: recommendations for healthcare professionals. BMC Palliat Care 2018;17:1–17. 10.1186/s12904-018-0332-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broad JB, Gott M, Kim H, et al. Where do people die? An international comparison of the percentage of deaths occurring in hospital and residential aged care settings in 45 populations, using published and available statistics. Int J Public Health 2013;58:257–67. 10.1007/s00038-012-0394-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vossius C, Selbæk G, Šaltytė Benth J, et al. Mortality in nursing home residents: a longitudinal study over three years. PLoS One 2018;13:e0203480. 10.1371/journal.pone.0203480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braggion M, Pellizzari M, Basso C, et al. Overall mortality and causes of death in newly admitted nursing home residents. Aging Clin Exp Res 2020;32:275–80. 10.1007/s40520-019-01441-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Honinx E, van Dop N, Smets T, et al. Dying in long-term care facilities in Europe: the PACE epidemiological study of deceased residents in six countries. BMC Public Health 2019;19:1–12. 10.1186/s12889-019-7532-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pivodic L, Smets T, Gambassi G, et al. Physical restraining of nursing home residents in the last week of life: an epidemiological study in six European countries. Int J Nurs Stud 2020;104:103511. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mignani V, Ingravallo F, Mariani E, et al. Perspectives of older people living in long-term care facilities and of their family members toward advance care planning discussions: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. Clin Interv Aging 2017;12:475–84. 10.2147/CIA.S128937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andreasen P, Finne-Soveri UH, Deliens L, et al. Advance directives in European long-term care facilities: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2019. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001743. [Epub ahead of print: 21 May 2019]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilissen J, Pivodic L, Wendrich-van Dael A, et al. Nurses' self-efficacy, rather than their knowledge, is associated with their engagement in advance care planning in nursing homes: a survey study. Palliat Med 2020;34:917–24. 10.1177/0269216320916158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evenblij K, Ten Koppel M, Smets T, et al. Are care staff equipped for end-of-life communication? A cross-sectional study in long-term care facilities to identify determinants of self-efficacy. BMC Palliat Care 2019;18:1–11. 10.1186/s12904-018-0388-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon J, Knapp M. Whose job? The staffing of advance care planning support in twelve international healthcare organizations: a qualitative interview study. BMC Palliat Care 2018;17:1–16. 10.1186/s12904-018-0333-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilissen J, Pivodic L, Wendrich-van Dael A, et al. Implementing advance care planning in routine nursing home care: the development of the theory-based ACP+ program. PLoS One 2019;14:1–20. 10.1371/journal.pone.0223586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilissen J, Pivodic L, Wendrich-van Dael A, et al. Implementing the theory-based advance care planning ACP+ programme for nursing homes: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial and process evaluation. BMC Palliat Care 2020;19:5. 10.1186/s12904-019-0505-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:1–12. 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffmann TC, Oxman AD, Ioannidis JP, et al. Enhancing the usability of systematic reviews by improving the consideration and description of interventions. BMJ 2017;358:1–8. 10.1136/bmj.j2998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilissen J, Pivodic L, Smets T, et al. Preconditions for successful advance care planning in nursing homes: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 2017;66:47–59. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Houben CHM, Spruit MA, Groenen MTJ, et al. Efficacy of advance care planning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014;15:477–89. 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korfage IJ, Rietjens JAC, Overbeek A. A cluster randomized controlled trial on the effects and costs of advance care planning in elderly care: study protocol. BMC Geriatr 2015;15:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ampe S, Sevenants A, Coppens E, et al. Study protocol for 'we DECide': implementation of advance care planning for nursing home residents with dementia. J Adv Nurs 2015;71:1156–68. 10.1111/jan.12601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smets T, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BBD, Miranda R, et al. Integrating palliative care in long-term care facilities across Europe (PACE): protocol of a cluster randomized controlled trial of the ‘PACE Steps to Success’ intervention in seven countries. BMC Palliat Care 2018;17:1–11. 10.1186/s12904-018-0297-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silvester W, Parslow RA, Lewis VJ, et al. Development and evaluation of an aged care specific advance care plan. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013;3:188–95. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Royal College of Physicians of London . Concise guidance to good practice: a series of evidence-based Guidelinesfor clinical management. number 12: advance care planning national guidelines, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rondia K, Raeymaekers P. Vroeger nadenken. over later [Thinking sooner. about later]. 55. Kon Boudewijnstichting, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Mechelen W. Vroegtijdige Zorgplanning. Richtlijn, Versie: 1.0. 2014.

- 26.LEIF . Negatieve wilsverklaring. Negatieve wilsverklaring - Weigeren is een recht.

- 27.Rietjens J, Korfage I, Taubert M. Advance care planning: the future. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2021;11:89–91. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilissen J, Pivodic L, Wendrich-van Dael A. Implementing the theory-based advance care planning ACP+ programme for nursing homes: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial and process evaluation. BMC Palliat Care 2020;19:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hower KI, Vennedey V, Hillen HA, et al. Is organizational communication climate a precondition for patient-centered care? Insights from a key informant survey of various health and social care organizations. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:1–17. 10.3390/ijerph17218074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernacki RE, Block SD, American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force . Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1994–2003. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rietjens JAC, Sudore RL, Connolly M, et al. Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: an international consensus supported by the European association for palliative care. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:e543–51. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30582-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.In der Schmitten J, Lex K, Mellert C. Patientenverfügungsprogramm: Implementierung in Senioreneinrichtungen. implementing an advance care planning program in German nursing homes. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014;111:50–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flo E, Husebo BS, Bruusgaard P, et al. A review of the implementation and research strategies of advance care planning in nursing homes. BMC Geriatr 2016;16. 10.1186/s12877-016-0179-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tilburgs B, Vernooij-Dassen M, Koopmans R, et al. Barriers and facilitators for GPs in dementia advance care planning: a systematic integrative review. PLoS One 2018;13:1–21. 10.1371/journal.pone.0198535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gilissen J, Pivodic L, Gastmans C, et al. How to achieve the desired outcomes of advance care planning in nursing homes: a theory of change. BMC Geriatr 2018;18:1–14. 10.1186/s12877-018-0723-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jimenez G, Tan WS, Virk AK, et al. Overview of systematic reviews of advance care planning: summary of evidence and global lessons. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;56:436–59. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ten Koppel M, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van der Steen JT, et al. Care staff's self-efficacy regarding end-of-life communication in the long-term care setting: results of the PACE cross-sectional study in six European countries. Int J Nurs Stud 2019;92:135–43. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjspcare-2021-003008supp001.pdf (1.2MB, pdf)