Abstract

目的

探究破骨细胞分化在颞下颌关节骨关节炎(TMJOA)发生中的作用。

方法

构建小鼠TMJOA模型,Micro-CT观察TMJOA发生发展过程中髁突骨质变化,苏木素伊红(HE)染色观察TMJOA关节组织学结构变化,抗酒石酸酸性磷酸酶(TRAP)组织染色观察TMJOA关节组织中破骨细胞的存在情况。收集TMJOA患者滑液,检测其对破骨细胞分化的作用。

结果

Micro-CT观察到TMJOA小鼠髁突在第2周和第3周时破坏最明显,形态也发生鸟嘴样改变;HE染色观察到TMJOA小鼠在第2周髁突软骨及软骨下骨结构紊乱;TRAP组织染色显示第2周时关节髁突中破骨细胞数量明显增多;细胞实验结果显示TMJOA患者滑液刺激后的破骨细胞分化数量显著增多,细胞体积变大。

结论

TMJOA动物模型及TMJOA患者滑液细胞实验均可诱导破骨细胞分化,表明破骨细胞分化在颞下颌关节骨关节炎的发生中起重要作用。

Keywords: 颞下颌关节骨关节炎, 滑液, 破骨细胞, 髁突, 破骨分化

Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to explore the role of osteoclast differentiation in the occurrence of temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis (TMJOA).

Methods

A mouse TMJOA model was constructed. Micro-CT was used to observe the changes in condylar bone during the development of TMJOA. Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining was used to observe the histological structure changes of the condyle of TMJOA mice. Tartrate resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining was used to observe the presence of osteoclasts in TMJOA joint tissue. The synovial fluid of patients with TMJOA was collected to determine the effect on osteoclast differentiation.

Results

Micro-CT revealed that the condyle of the TMJOA group had the most obvious damage in the second and third weeks, and the shape of the condyles also changed in a beak-like manner. HE staining showed that the condyle cartilage and subchondral bone structure of TMJOA mice were disordered in the second week. TRAP tissue staining showed that the number of osteoclasts of the TMJOA group obviously increased in the second week. Results of cell experiments showed that the number of osteoclast differentiation significantly increased after stimulation of synovial fluid from TMJOA patients, and the cell volume increased.

Conclusion

TMJOA animal models and TMJOA patient synovial cell experiments could induce osteoclast differentiation, indicating that osteoclast differentiation plays an important role in TMJOA occurrence.

Keywords: temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis, synovial fluid, osteoclast, condyle, osteoclast differentiation

颞下颌关节骨关节炎(temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis,TMJOA)是临床常见的困扰患者的一种疾病,是颞下颌关节紊乱病(temporomandibular joint disorder,TMD)中的主要疾病之一,患者大多表现为疼痛以及关节功能障碍,极大地影响了患者的生活质量[1]。在影像学上,绝大多数TMJOA患者往往显示有明显的髁突骨质吸收和破坏,部分患者经过治疗后显示骨质破坏后的重建。骨质的破坏及改建需要破骨细胞的参与,目前为止破骨细胞在TMJOA中的作用并不清楚。

近年来许多研究表明,TMJOA的发生发展过程中伴随着破骨细胞活性及功能的改变。通过机械性超负荷建立的TMJOA大鼠模型中,缺氧诱导因子(hypoxia-inducible factor,HIF)-1α被激活,抑制骨保护素(osteoprotegerin,OPG)的表达,导致破骨细胞的分化及数量增多[2]。在实验性单侧前牙咬合构建的小鼠TMJOA模型中也发现了软骨下小梁骨的丢失,破骨细胞活性增强[3]。研究[4]发现,软骨下骨的病理改变在TMJOA中至关重要,通过使用瑞巴派特抑制破骨细胞活性和分化可以减少软骨下骨丢失,从而减轻TMJOA的髁突变性。也有研究[5]表明,使用炎性抑制剂白细胞介素(interleukin,IL)-37b可以抑制破骨细胞形成,有可能成为预防TMJOA的新靶点。本研究通过碘乙酸钠(monosodium iodoacetate,MIA)建立TMJOA模型,应用抗酒石酸酸性磷酸酶染色(tartrate resistant acid phosphatase,TRAP)观察TMJOA关节组织中破骨细胞的存在情况,同时在临床上收集TMJOA患者滑液,对破骨细胞进行刺激,进一步证实破骨细胞分化在TMJOA的发生中的作用。

1. 材料和方法

1.1. 材料

RAW264.7细胞系(美国模式培养物集存库,美国),MIA、TRAP试剂盒(西格玛奥德里奇公司公司,美国)、苏木素伊红(hematoxylin and eosin,HE)(武汉谷歌生物科技有限公司)、高糖杜尔伯科改良伊格尔培养基(Dulbecco's modified eagle medium,DMEM)、胎牛血清(fetal bovine serum,FBS)(北京海克隆生物化学制品有限公司)、重组小鼠核因子-κB受体活化因子配体(receptor activator for nuclear factor-κB ligand,RANKL)(R&D system公司,美国)、细胞计数试剂盒8(cell counting kit-8,CCK8)(上海东仁化学科技有限公司)。

1.2. 小鼠TMJOA模型构建

从湖北省疾控中心购买40只SPF级别的C57雄性小鼠,体重约为每只20 g,分为MIA组和盐水组,每组20只小鼠,对于MIA组小鼠,双侧颞下颌关节(temporomandibular joint,TMJ)上腔注入20 µL浓度为1 mg/50 µL MIA溶液建立TMJOA模型,盐水组小鼠双侧TMJ上腔注入20 µL生理盐水作为对照[6]。分别在1、2、3、4周时对小鼠(每周5只)进行安乐死,通过腹腔注射过量的戊巴比妥钠溶液致死小鼠,取小鼠TMJ标本。动物实验的实验步骤已获得武汉大学口腔医学院伦理委员会的批准(批准号:S07919020F)。

1.3. Micro-CT检测

将上述建模后的MIA组和盐水组小鼠的TMJ标本在4%多聚甲醛中固定24 h,然后冲水过夜,然后每周每组取4个标本通过SkyScan1176型Micro-CT仪(布鲁克公司,德国)对标本进行三维分析,观察TMJOA模型的构建情况以及小鼠TMJ髁突骨质的破坏情况,通过Micro-CT分析软件CTAn分析MIA组和盐水组小鼠髁突软骨下骨的骨小梁间距(trabecular separation,Tb.Sp)是否存在差异。

1.4. HE染色

将Micro-CT扫描后的32只关节标本以及其余未进行扫描的8只关节标本一起置于10%乙二胺四乙酸(ethylene diamine tetraacetic acide,EDTA)中脱钙2个月。脱钙完成后,将标本在梯度乙醇中进行脱水,石蜡包埋,4 µm进行连续切片,烤片备用;将切片标本置于梯度乙醇中脱蜡入水,滴加苏木素溶液浸染3 min,流水冲洗3 min,彻底冲去染液;然后滴加伊红溶液浸染30 s,流水冲洗5 s;将玻片放置在通风橱中风干,二甲苯透明,中性树脂封片;最后在显微镜下观察拍照。

1.5. TRAP染色

将上述烤片完成后的切片标本置于梯度乙醇中脱蜡入水,按照TRAP试剂盒的步骤配置染液,避光滴染,在37 °C温箱中孵育1 h;蒸馏水洗3次,每次3 min;苏木素复染50 s,冲水反蓝;待自然干燥,透明,封片。对培养的破骨细胞进行染色时,首先,吸除掉培养皿中的培养基,生理盐水浸洗3次,每次3 min;按照TRAP试剂盒的步骤配置细胞固定液并加入皿中,30 s;吸除固定液,生理盐水浸洗3次,每次3皿;避光下,将配置好的染色液滴入皿中,在37 °C温箱中孵育1 h;然后吸出染色液,生理盐水浸洗3次,每次3 min,最后在显微镜下观察拍照。

1.6. 培养RAW264.7细胞系并诱导分化为破骨细胞

将RAW264.7细胞系置于含10%FBS和90%DMEM的培养基中,在37 °C、95%O2、5%CO2的培养箱中孵育,每1~2 d在显微镜下观察细胞生长情况和贴壁状况,并更换培养液,待细胞贴满皿底50%~60%时进行传代培养[7]。

将刚传代的RAW264.7细胞置于含有10%FBS和90%DMEM的培养基中,并向培养基中加入10 ng·mL−1的RANKL,在37 °C、95%O2、5%CO2的培养箱中孵育,每天在显微镜下观察细胞的生长情况和贴壁状况,大约1周左右可观察到破骨细胞的分化。

1.7. 关节滑液对破骨细胞生长以及分化的影响

1.7.1. 收集滑液

TMJOA组的滑液取自TMJOA患者,共6例,都为女性,12~53岁。采集方法:取含2 mL生理盐水的5 mL注射器,将生理盐水注入患者TMJ上腔,然后抽回,反复灌洗3次,最终得到2 mL稀释后的关节腔滑液。将得到的滑液在4 °C下离心,弃去下方沉淀的血块,保存于−80 °C冰箱,将此作为滑液样本的原液[8]。人体研究获得武汉大学口腔医学院伦理委员会的批准(批准号:2014LUNSHENZI24),患者签署知情同意书。

1.7.2. 滑液对细胞生长的影响

将刚传代的RAW264.7细胞分为8个组,第1组为RAW264.7细胞;第2组为RAW264.7细胞加入RANKL刺激;第3~8组为RAW264.7细胞加入RANKL刺激,同时分别加入6个不同患者的10%浓度的滑液原液。以上8组均置于10%FBS、90%DMEM的培养基中,在37 °C、95%O2、5%CO2的培养箱中孵育,每天在显微镜下观察细胞的生长和分化情况,1周后按照说明书对细胞进行CCK8实验,通过NanoDrop 1000型紫外分光光度仪(赛默飞世尔科技有限公司,美国)测量细胞在450 nm处的吸光光度(optical delnsity,OD)值,统计OD值并分析各组之间的OD值是否有差异,进而分析各组之间细胞生长活性是否有差异。

1.7.3. 滑液对破骨细胞分化的影响

将刚传代的RAW264.7细胞分为空白对照组、对照组和刺激组,空白对照组加入10%FBS、80%DMEM和10%生理盐水;空白对照组加入10%FBS、80%DMEM、10 ng·mL−1 RANKL和10%生理盐水,刺激组中加入10%FBS、80%DMEM、10 ng·mL−1 RANKL和10%TMJOA患者滑液,该滑液是从上述6名患者滑液样本中随机选取的一个。每天在显微镜下观察细胞的生长情况和分化情况,并拍照记录。

1.8. 统计学处理

采用GraphPad Prism8对数据进行分析,数据采用x±s表示,通过t检验来比较组间差异,对组间和组内差异采用方差分析。P<0.05表示具有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1. 建模观测

2.1.1. 小鼠TMJOA动物模型Micro-CT分析结果

Micro-CT结果显示:盐水组髁突形态正常,骨质结构完整;MIA组1周时髁突骨质有轻微破坏,骨白线模糊,2周和3周骨质破坏严重,出现骨小梁稀疏与减少,同时髁突表面形态改建,可同时观察到骨质增生和吸收;4周时骨质破坏减轻,2周时MIA组骨小梁间距高于盐水组,差异有统计学意义(P<0.000 1)(图1、2)。

图 1. 盐水组和MIA组髁突骨质Tb.Sp结果统计.

Fig 1 Statistics of Tb.Sp results of condylar bone in saline group and MIA group

*MIA组与盐水组相比,差异有统计学意义;#MIA组间相比,差异有统计学意义,****P<0.000 1,###P<0.000 5,####P<0.000 1;ns差异无统计学意义。

图 2. 盐水组和MIA组在不同时间点髁突骨质情况.

Fig 2 The condylar bone condition of saline group and MIA group at different time points

2.1.2. HE染色结果

建模第2周,显微镜下HE染色显示,盐水组软骨层次清楚,软骨下骨结构正常;MIA组软骨细胞凋亡,层次不清,软骨下骨结构紊乱(图3)。

图 3. TMJ髁突第2周HE染色.

Fig 3 HE staining of condyle of TMJ in the second week

A:盐水组 × 100;B:盐水组 × 200;C:MIA组 × 100;D:MIA组 × 200。

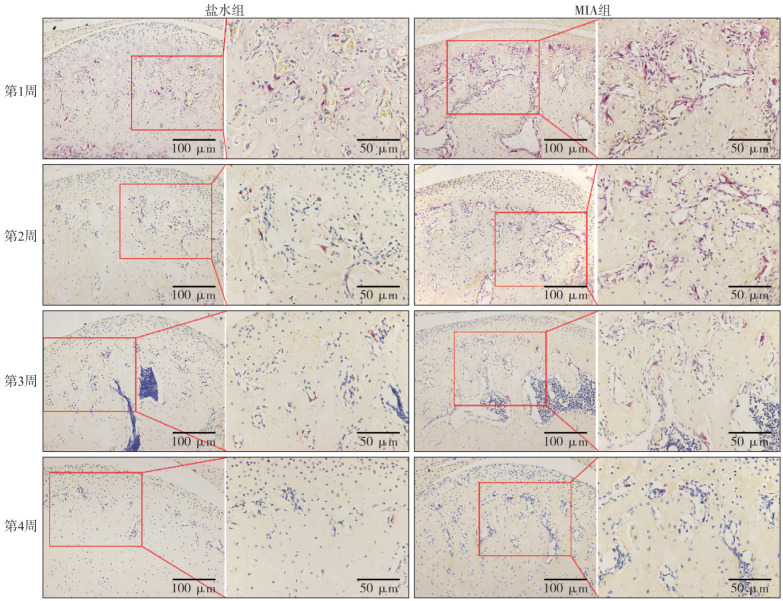

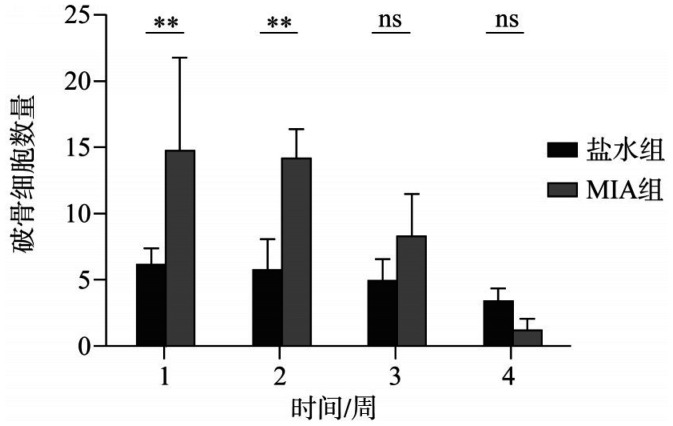

2.2. TRAP染色结果

1周和2周MIA组的关节区域破骨细胞数量增多,差异有统计学意义(P<0.005),3周和4周时,两组关节区域的破骨细胞数量区别不大(图4、5)。

图 4. 盐水组和MIA组髁突不同时间点TRAP染色.

Fig 4 TRAP staining of condyle in saline group and MIA group at different time points

图 5. 盐水组和MIA组在不同时间点破骨细胞数量统计.

Fig 5 The number of osteoclasts in saline group and MIA group was counted at different time points

**P<0.005;ns差异无统计学意义。

2.3. TMJOA患者滑液促进破骨细胞分化

第3~8组与第1、2组的OD值之间的差异无统计学意义,即可认为其细胞活性的差异无统计学意义(图6),即细胞活性是相同的,因此可以认为滑液的细胞毒性对细胞的生长无明显影响。

图 6. 细胞活性检测.

Fig 6 Cell viability test

ns差异无统计学意义。

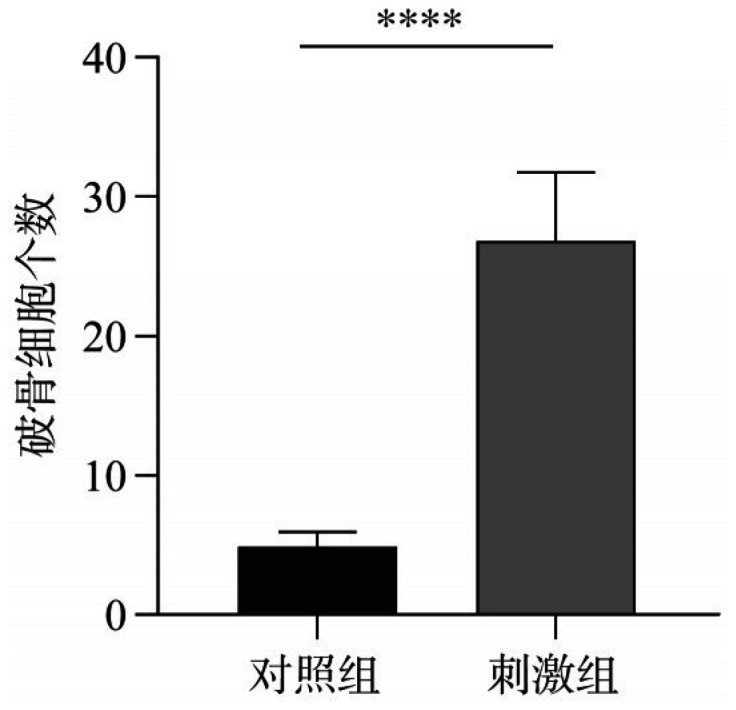

RAW264.7细胞生长情况如图7所示,诱导分化的破骨细胞多核(大于等于2个核),呈紫红色,细胞体积远大于分化前RAW264.7细胞,加入TMJOA患者滑液刺激后,破骨细胞的分化明显增多,且细胞体积大小也相比对照组更大;刺激组破骨细胞数量多于空白对照组,差异有统计学意义(P<0.000 1)(图8)。

图 7. 破骨细胞分化情况.

Fig 7 The differentiation of osteoclasts

左:空白对照组RAW264.7细胞生长情况;中:对照组无滑液刺激的破骨细胞生长情况;右:刺激组滑液刺激的破骨细胞生长情况。第一行:× 100;第二行:× 200。

图 8. 对照组和刺激组破骨细胞数量统计.

Fig 8 The number of osteoclasts in control group and stimulation group was statistically analyzed

****P<0.000 1。

3. 讨论

本研究发现在TMJOA小鼠模型中,通过Micro-CT可以观察到骨白线的消失,出现骨小梁稀疏与减少,同时髁突表面形态改建,组织学上发现髁突破骨细胞增多,髁突骨质破坏,提示破骨细胞可能参与TMJOA的发生及发展。

在完全弗氏佐剂(complete Freund's adjuvant,CFA)诱导的炎性TMJ中,炎症前期破骨细胞数量显示增多,同时髁突骨质丢失严重,而这种TMJ炎症状态是TMJOA的重要危险因素[9];在MIA注射诱导的TMJOA中,髁突出现比较明显的骨破坏[10]。也有研究[5]发现,炎症抑制剂IL-37b可以通过抑制破骨细胞的形成来预防TMJOA。破骨细胞抑制剂阿仑膦酸钠,可以改善膝关节OA大鼠的疼痛程度[11]。

关节滑液是TMJ重要成分,在TMJOA中有重要作用。在TMJOA疾病过程中,往往伴随着滑膜炎症,同时滑膜组织分泌的滑液成分会发生很大变化[12]。以往的研究表明,滑膜炎症后导致促炎因子的分泌增多或者是通过促进血管化来参与TMJOA的疾病进展。在TMJOA患者滑液中,已经检测到几种炎性细胞因子的水平升高,如IL-12、IL-1β、IL-6和肿瘤坏死因子-α[13],这些促炎因子可通过核因子(nuclear factor,NF)途径,调节金属基质蛋白酶的表达来影响关节内的分解代谢。同时研究[14]–[15]发现,与血管生成相关的细胞因子,如血管内皮生长因子(vascular endothelial growth factor,VEGF)、高迁移率族盒染色体蛋白-1等,在滑液、关节盘等组织中的表达均升高,这些促血管生成因子可以促进血管长入到无血管结构的关节盘和软骨,进而影响其结构与功能。更有研究[16]表明,低氧又可诱导VEGF激活,通过HIF-1α-VEGF-Notch途径促进髁突软骨的血管生成。这些炎症因子和促血管生成因子通过一系列的信号通路,可能同时也对破骨细胞的分化及活性起到调控作用,进而引起软骨下骨的骨质吸收、紊乱和改建[17]。

有研究[18]表明,TMD患者的滑液可以诱导破骨细胞分化,在膝关节置换术后并发假体周围关节感染的患者滑液中,IL-16含量增高,IL-16可以通过依赖于c-Jun氨基末端激酶/丝裂原活化蛋白激酶信号通路,活化激活T细胞核因子1蛋白(nuclear factor of activated T-cells, cytoplasmic 1,NFATc1),直接导致单核细胞分化为破骨细胞样细胞。本研究发现,TMJOA患者滑液可以在体外促进破骨细胞分化,TMJ腔内的滑液可能通过影响破骨细胞的活性与分化来介导TMJOA的疾病进程。

以往大量研究探索了破骨细胞分化和功能活性的具体机制,除了经典的通过集落刺激因子、RANKL等细胞因子调控,激活NF-κB和NFATc1等重要信号通路,从而刺激破骨细胞分化外。近年来,有研究发现了独立于RANKL途径的促进破骨细胞分化的机制,包括肿瘤坏死因子超家族成员T淋巴细胞表达的受体、增殖诱导配体和B细胞活化因子,以及生长转化因子-β、IL-6、IL-8、IL-11和神经生长因子等。但是,在这些促进破骨细胞分化的分子机制中,还需要进一步研究哪些与TMJOA滑液刺激破骨细胞分化有关,同时,也更需要探索新的可能的分子通路来阐明TMJ骨关节病的致病机制。

总而言之,TMJOA中滑液成分与破骨细胞分化数量及其活性较为相关,但主要起作用的成分以及其中具体的作用机制还不甚清楚,还需要更多的研究来探索。

Funding Statement

[基金项目] 国家自然科学基金(81771100,81671013)

Supported by: The National Natural Science Foundation of China (81771100, 81671013).

Footnotes

利益冲突声明:作者声明本文无利益冲突。

References

- 1.Wang XD, Zhang JN, Gan YH, et al. Current understanding of pathogenesis and treatment of TMJ osteoarthritis[J] J Dent Res. 2015;94(5):666–673. doi: 10.1177/0022034515574770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shirakura M, Tanimoto K, Eguchi H, et al. Activation of the hypoxia-inducible factor-1 in overloaded temporomandibular joint, and induction of osteoclastogenesis[J] Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;393(4):800–805. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang T, Zhang J, Cao Y, et al. Wnt5a/Ror2 mediates temporomandibular joint subchondral bone remodeling[J] J Dent Res. 2015;94(6):803–812. doi: 10.1177/0022034515576051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Izawa T, Mori H, Shinohara T, et al. Rebamipide attenuates mandibular condylar degeneration in a murine model of TMJ-OA by mediating a chondroprotective effect and by downregulating RANKL-mediated osteoclastogenesis[J] PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0154107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo P, Feng C, Jiang C, et al. IL-37b alleviates inflammation in the temporomandibular joint cartilage via IL-1R8 pathway[J] Cell Prolif. 2019;52(6):e12692. doi: 10.1111/cpr.12692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang XD, Kou XX, He DQ, et al. Progression of cartilage degradation, bone resorption and pain in rat temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis induced by injection of iodoacetate[J] PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.王 瀚, 曹 新生, 张 舒. 破骨细胞体外培养技术[J] 中国骨质疏松杂志. 2014;20(11):1284–1289. [Google Scholar]; Wang H, Cao XS, Zhang S. The technique of osteoclast culture in vitro[J] Chin J Osteoporos. 2014;20(11):1284–1289. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li W, Long X, Jiang S, et al. Histamine and substance P in synovial fluid of patients with temporomandibular disorders[J] J Oral Rehabil. 2015;42(5):363–369. doi: 10.1111/joor.12265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu L, Guo H, Li C, et al. A time-dependent degeneration manner of condyle in rat CFA-induced inflamed TMJ[J] Am J Transl Res. 2016;8(2):556–567. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cui SJ, Zhang T, Fu Y, et al. DPSCs attenuate experimental progressive TMJ arthritis by inhibiting the STAT1 pathway[J] J Dent Res. 2020;99(4):446–455. doi: 10.1177/0022034520901710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu S, Zhu J, Zhen G, et al. Subchondral bone osteoclasts induce sensory innervation and osteoarthritis pain[J] J Clin Invest. 2019;129(3):1076–1093. doi: 10.1172/JCI121561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashraf S, Mapp PI, Walsh DA. Contributions of angiogenesis to inflammation, joint damage, and pain in a rat model of osteoarthritis[J] Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(9):2700–2710. doi: 10.1002/art.30422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vernal R, Velásquez E, Gamonal J, et al. Expression of proinflammatory cytokines in osteoarthritis of the temporomandibular joint[J] Arch Oral Biol. 2008;53(10):910–915. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.郭 慧琳, 房 维, 邓 末宏, et al. 人颞下颌关节骨关节炎滑膜成纤维细胞中血管生成及润滑相关因子的表达[J] 口腔医学研究. 2018;34(3):270–273. [Google Scholar]; Guo HL, Fang W, Deng MH, et al. Expression of angiogenic-associated and lubrication-associated factors in synovial fibroblasts of temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis[J] J Oral Med Res. 2018;34(3):270–273. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng Y, Fang W, Li C, et al. The expression of high-mobility group box protein-1 in temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis with disc perforation[J] J Oral Pathol Med. 2016;45(2):148–152. doi: 10.1111/jop.12336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y, Zhao B, Zhu Y, et al. HIF-1-VEGF-Notch mediates angiogenesis in temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis[J] Am J Transl Res. 2019;11(5):2969–2982. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.惠 婷, 张 广灿, 冯 丹丹, et al. 神经肽P物质及骨形态发生蛋白信号通路在ST2细胞成骨分化过程中的作用[J] 华西口腔医学杂志. 2018;36(4):378–383. doi: 10.7518/hxkq.2018.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hui T, Zhang GC, Feng DD, et al. Role of neuropeptide substance P and the bone morphogenetic protein signaling pathway in osteogenic differentiation of ST2 cells[J] West China J Stomatol. 2018;36(4):378–383. doi: 10.7518/hxkq.2018.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demir CY, Ersoz ME. Biochemical changes associated with temporomandibular disorders[J] J Int Med Res. 2019;47(2):765–771. doi: 10.1177/0300060518811009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]