Abstract

The year 2020 was also about the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth. On this occasion, his rarely discussed life and death masks should be presented. In addition, a short historical outline is given of the history of face masks in general, which now accompanies us in everyday life in the form of the face–nose mask due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Beethoven, Vienna, Death mask, Life mask, History of medicine

Abstract

Im Jahr 2020 jährte sich der Geburtstag Beethovens zum 250. Mal. Aus diesem Anlass werden seine selten besprochenen Lebend- und Totenmasken näher beleuchtet. Zudem wird ein kurzer geschichtlicher Abriss über die Geschichte der Gesichtsmasken i. Allg. gegeben, die uns in Form der Mund-Nasen-Maske aufgrund der COVID-19-Pandemie derzeit im Alltag begleitet.

Schlüsselwörter: Beethoven, Wien, Totenmaske, Lebendmaske, Geschichte der Medizin

Face masks in general

The term “mask” is used nowadays in so many different ways; e.g., when visiting a film set, we encounter this term as a place where actors are made up for their appearance. Furthermore, people who portray their feelings differently to the outside world are said to wear a “mask”. There are face masks used in a carnival, as well as life and death masks. There are also ritual masks, ancient theatre masks, shameful masks, Venetian half masks and protective masks.

In principle, the word “mask” is derived from the Arabic word mashara (قناع) and can be translated as a fool, farce, teasing or joke. It is a face covering that can consist of different materials. Depending on the era, time and place of origin, masks can consist of parts of plants, leather, wood, clay and fabrics, or even plastic [1].

Face masks have a long tradition. Their origin lies primarily in the cultural or religious rites that gained importance through religious acts such as dances by ethnic groups or indigenous peoples. They served to worship protective deities or to scare off evil spirits. The wearer of such a mask is not simply disguised, but represents a position of power in the community. The production of these ritual masks only takes place under strict ritual regulations, in which the masks are given a special so-called power charge.

In non-European cultures (Egypt, China, Mesoamerica) the face of a high-ranking deceased (ruler or priest-king) was sometimes covered with a precious stone or metal mask (gold, bronze) in the course of the burial ceremony, without resemblance to the living person. We further have to distinguish the more modern “portrait” or “memory masks”, which were reworked and often presented an idealized picture of the portraited person. Those masks were never given to the grave. On the other hand, so-called funeral masks should remember the person as he or she was at the moment of death, thus displaying more realistic features of their face [1].

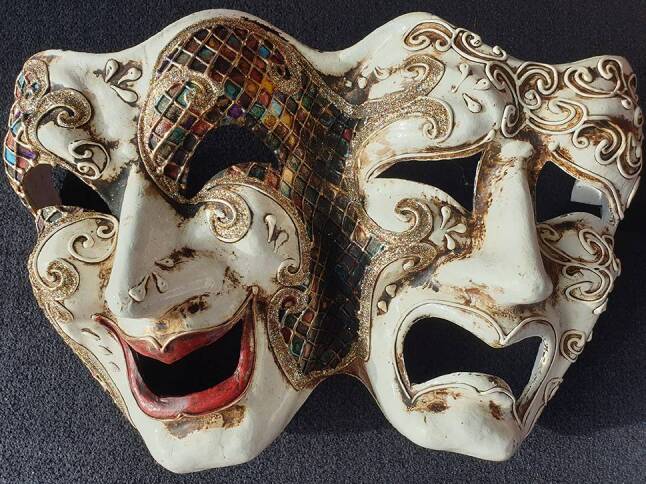

In ancient Greek, the well-known theatrical masks probably originated from ritual masks, because there was a wide spread of cultural gods at that time. For instance, as part of the Dionysius cult, dances were performed, whereas tragedies and comedies were accompanied by choirs. Over time, certain repeating characters developed who faced only new adventures. As such characters appeared, again and again, role-specific and easily recognisable masks were used. These recurring masks were increasingly adapted, according to their use, to better express the feelings of the specific acting role. This is why the laughing mask emerged lastly as a symbol for comedy and the sad mask for tragedy. These symbols are used to this day in our theatres, ballets and operas (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Theatre masks as symbols for tragedy and comedy. (Collection Sedivy)

In the Middle Ages, masks of shame appeared. These masks were mostly made of metal and were used by the courts for punishment. The loss of the face due to such masks was accompanied by a great disgrace and dishonour for the punished person. It was also intended to show how the criminal is seen by society. For example, if someone behaved “like a pig” by slandering others, his head was covered by an iron boar head that also paralyzed his tongue. Noteworthily, this kind of punishment existed until the 18th century. Similar intentions were pursued in schools up to the 20th century. Children who did not obey the rules were given dog-eared hats and were exposed in front of their classmates.

From ritual festivals, which celebrated the change from the cold winter half-year to the warm and fertile summer half-year, carnival festivals and balls emerged. The rustic version aimed to drive away the winter by disguising themselves as ghosts, goblins and creepy figures wearing wooden masks. Those parades (Krampuslauf, Perchtenlauf) are still preserved up to now in the Alpine region in the rural parts of Austria, Switzerland, Bavaria, Slovenia, western and northern Croatia and northeastern Italy. Carnival is claimed to derive as local pre-Christian rituals from such rites involving masked figures of the Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht. The word Carnival is of Christian origin and closely related to Lent; it is derived from the late Latin carne levare, which means “remove meat”. Carnival, therefore, represented the last period of feasting and celebration before the spiritual rigors of Lent [2].

Most famous for its distinctive masks is the Carnival of Venice that ends with the Christian celebration of Lent, 40 days before Easter, on Shrove Tuesday (Martedì Grasso or Mardi Gras), i.e., the day before Ash Wednesday. In addition, the nobility of the Venetian society also held masquerades to showcase their power and wealth wearing half masks, which covered only the eye area. Furthermore, those masks gave the wearer a form of anonymity and allowed him/her to be whoever they wanted to be. Thus, such masks were also used to protect anonymity, such as in the case of the Austrian Emperor Josef II, who intended to travel unrecognised through Venice. However, such preservation of anonymity launched violence with an increase in crime. Nowadays, sometimes, e.g., clown masks and other facial larvae, are used for crimes such as homicide or bank robbery.

Similarly, here in Vienna, the traditional masked ball Rudolfina Redoute has been celebrated on Shrove Monday since 1899. This ball is known for its mysterious flair elicited by the colourful masking of the women, who are wearing half masks connected with women’s choice. At midnight at the end of the unmasking quadrille (which is the Fledermaus-Quadrille by Johann Strauss son) women take off their masks.

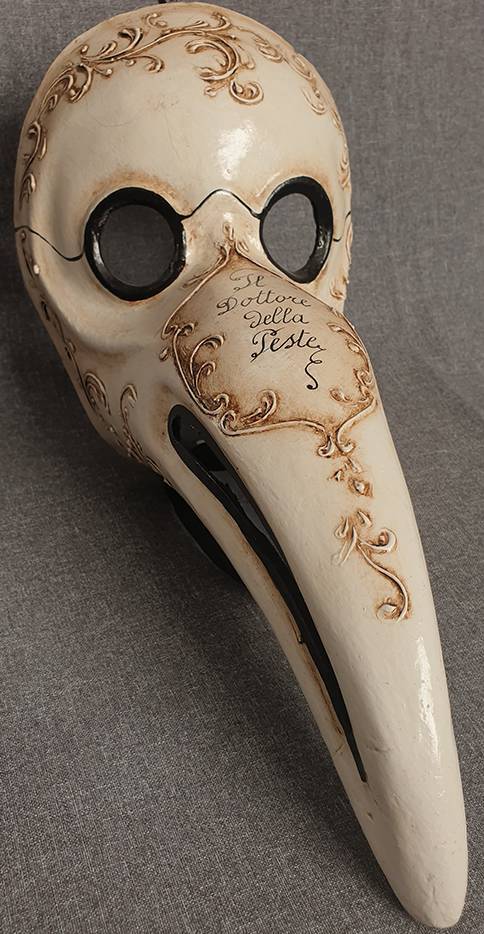

Nevertheless, to this day, festival masks are worn at Halloween, Mardi Gras, and Carnival. And last but not least, we all have to wear mouth and nose masks, such as surgeons, to protect us from the coronavirus. Masks as a protective measure were already used in the Middle Ages. They were often made of leather and, in addition to coats and gloves, served as protection for doctors when treating infectious patients, e.g., those suffering from the plague. Some of the masks were designed in such a way that they could emit smoke, often they were filled with herbs and liquids—probably primarily intended as protection against the miasmas in the air, which were considered to be the carriers of the infections (Fig. 2). In 1897 in Breslau, Johann von Mikulicz-Radecki first used a mask that consisted of a layer of gauze bandage [3].

Fig. 2.

Plague doctor mask to protect from “bad air” and prevent contagion. Such masks have lenses on the eyes and a long cavity in the nose that was filled with drugs and aromatic items. The shape of this cavity was very similar to beaks of birds. At the beak there were substances such as ambergris, mint leaves, storax, myrrh, laudanum, rose petals, camphor, cloves and straw. (Photo from replica, collection Sedivy)

Funeral or death masks and life masks

In ancient times, a new kind of face mask appeared that developed from ritual masks. In a kind of religious-magical context, either moulds were taken or images were formed of the dead face and were embedded, e.g., in an ancestral cult to ensure immortality. Those funeral masks sometimes displayed a more glorified image of the deceased person and were placed on the face before or during burial rites. The masks were often buried with the dead. Well known to us are those from ancient Egypt, e.g., of Tutankhamun, and from Mycenaean Greece, such as that of Agamemnon (Fig. 3). Moreover, such funeral or sepulchral masks are supposed to ward off calamity or demons, might give the deceased a dignified appearance and may help the wandering spirit to find its body again. They are thought for the dead and laid together with them in the grave, whereas “classical”/modern death masks are made for the bereaved and stay with them.

Fig. 3.

Masks of Tutankhamun (a) & Agamemnon (b) (photos from replicas; collection Sedivy)

The classical death mask, however, should depict the face of the deceased either for remembrance as a mechanical reproduction or freely designed closely to his or her death. In some cultures, they are supposed to give strength to the bereaved and provide a picture of the deceased for the family tree and used for ancestor worship. They may also be used for the creation of portraits. In Europe, it was common that death masks were displayed at funerals. Sometimes a coffin portrait served as another option for such a presentation. Especially during the Italian Renaissance, such plaster casts of the deceased served sculptors as models for portraits of the dead persons. In France, at the end of the Middle Ages, it was customary to adapt the death mask in a lifelike manner. Glass eyes were inserted into the mask and artificial hairs were put on it. Thus, those masks became more a kind of a doll to be exhibited in public and are thus called effigies. The advantage was that funeral ceremonies could last several days beyond the time of death.

From the late 18th century onwards, scientists wanted to record variations in human physiognomy. In this measuring century, scientists used those masks in ethnography, archaeology, criminology and also for so-called race studies. Facial features, especially of famous people or notorious criminals, were of interest. It was, for instance, the anatomist and brain scientist Franz Joseph Gall who developed the concept of “phrenology” in the early 19th century that was later on discredited. Gall collected hundreds of casts of scholars, poets and statesmen, but also of criminals [1, 4, 5].

In some instances, the complete head was stored, such as of Luigi Lucheni (Fig. 4), the assassinator of Empress Elisabeth of Austria. His head was stored for many centuries and only buried in the year 2000. Such face masks were also used to describe so-called racial differences and were sometimes very helpful for forensic purposes to permanently record the facial features of unknown corpses for identification. At the time before the widespread availability of photography, it was the best option to preserve the face of a missing person to be recognized later. Moreover, life masks also became increasingly common to study their facial features.

Fig. 4.

Portrait of L. Lucheni according to the memory of R. Sedivy. (Water colour painting by Sabrina Tschudin [Madame Nadel]. With kind permission of Mrs. Tschudin, Fraubrunnen BE, Switzerland, 2020)

Furthermore, mourning portraits were also painted, often showing the person lying in peaceful rest, as done for Beethoven (Fig. 5). It is said that a new tradition of death masks started that of Lessing in 1781. It was the first to be made just to remember the deceased. This fact goes along with the basic mood of the romantic natural philosophy and the period of Romanticism (roughly between 1770–1848), where one longed for the infinity of nature and the human being. Romanticism emphasised emotion and individualism and was primarily a counter-reaction to the mechanic-technical dominance of the Industrial Revolution. It was a revolution against the aristocratic social and political norms of the Enlightenment, and the complete scientific rationalization of nature. In contrast to callous Rationalism and Classicism, Romanticism revived Medievalism. Preferring the medieval rather than the classical, a glorification began of all the past and nature; intense emotion was emphasized as an authentic source of aesthetic experience, placing emotions such as apprehension, horror and terror, and awe in a new light. The confrontation of the new aesthetic of the sublimity and beauty of nature became more important than pure quantification and scientific description. They were also intended for the preservation of the face of death, in the sense of Philippe Ariès, who introduced the concept of aestheticization. The aim was to capture the facial expression at the very moment of death as a phenomenon of nature [6, 7].

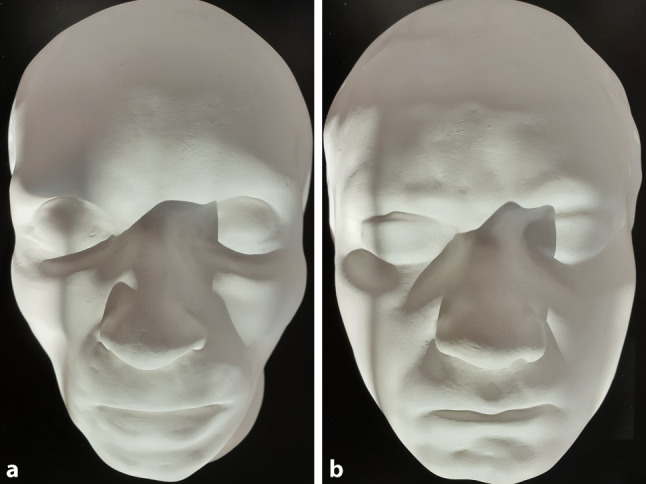

Fig. 5.

Death (a) & life mask (b) of Beethoven: plaster casts that were made from the originals, available at the Beethoven House in Bonn (photos of replicas, collection Sedivy)

In this regard, death masks take on the meaning of the image of nature with its special aesthetics and the glorification of a deceased person, often a celebrity.

Remembrance masks of celebrities

In regard to death masks, celebrities have always been in the foreground. The oldest surviving death mask is said that of Dante Alighieri, although scholars have justified doubts as to the authenticity of the exhibited mask in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. The oldest documented and preserved death mask is that of the canonized Franciscan Bernardino da Siena, who died in 1444.

In the course of time, several masks appeared, such as those of royals and aristocrats (e.g. Henry VIII., Friedrich the Great or Peter the Great), as well as of composers (e.g., Ludwig van Beethoven, Frédéric Chopin, Joseph Haydn, Franz Liszt), military and political leaders (e.g., Napoleon Bonaparte, Oliver Cromwell, Alexander I., Stalin, Abraham Lincoln), philosophers and poets (e.g., Friedrich Nietzsche, Friedrich Schiller, Voltaire, Torquato Tasso) and scientists (e.g., Blaise Pascal, Nikola Tesla).

The next lines will present the special example of the famous musician Beethoven, who was the first of whom a life mask and a death mask were taken.

“… to take a gypsy print from the corpse”—Beethoven’s life and death mask

In 1827 on March 26, early in the morning, Johann Matthias Ranftl (academic painter of the Biedermeier period) knocked on Carl Danhausers’s door and reported that Beethoven had died. As they had a plaster stone foundry in their house, his brother Josef Danhauser (also an academic painter) had the idea to draw up a death mask from the great dead man. Carl and Josef Danhauser, both of whom were admirers but not from Beethoven’s close circle of friends, arrived early that day at the deceased’s house and did not found anyone. However, a resident woman passed by and escorted the two men to Beethoven’s apartment. Finally, they stood in the anteroom in front of a locked door and opened it. At the back of the room behind the door, there was the bed with Beethoven’s body.

They recognised that during the period of illness, Beethoven’s beard had grown very much. They then organised a barber who shaved it off. In the end, Carl Danhauser bought the knife from the barber as a souvenir. They also took two locks of hair from Beethoven’s temple. His brother Josef, who first wanted to make the death mask by himself, finally accepted the help of the plaster caster, preferring to hand over the casting procedure to a skilled craftsman. Due to two contradicting records, a debate arose as to when the death mask was taken. In 1888, Carl Danhauser wrote in his report on the origin of Beethoven’s locks that they went to Beethoven’s flat on the early morning of March 26. On the other hand, Anton Schindler (violinist and conductor who was Beethoven’s unpaid private secretary) published in his biography of Beethoven a letter of Stephan v. Breuning (a very close friend of Beethoven) that is dated with March 27. In it, Breuning described that a certain Joseph Danhauser “… wishes to take a gypsy print from the corpse.” As the autopsy was performed early in the morning of March 27, it was concluded that the death mask was taken after the necropsy ([8]; Fig. 5a).

Because of the different timepoints indicated in these two letters, the debate arose regarding when the death mask was taken exactly. At last, a forensic medical report was requested by the Beethoven Museum in Bonn to clarify this contradiction. Finally, Prof. Dr. Richard Hellmer from the department of forensic medicine in Bonn confirmed that the mask was taken after the autopsy [8].

In addition, Beethoven was the first person known with a life and a death mask (Fig. 5a, b). It happened that in 1812, the Viennese piano makers Nannette and Andreas Streicher, who were friends of Schiller and Beethoven, opened a piano salon, which they wanted to decorate with busts of famous musicians. For that reason, the sculptor Franz Klein was commissioned to create a realistic Beethoven bust. Notably, before 1805, Klein had made busts for Franz Joseph Gall for his science of phrenology. Klein used plaster stone for Beethoven’s mask. The composer’s face had to be oiled and smeared with liquid plaster. Beethoven could only breathe through two small tubes inserted into his nostrils. But unfortunately, the great musician was afraid of suffocating and thus tore off the plaster layer. Thus, a second attempt was necessary to receive a useful cast. Franz Klein poured out the negative form that was created in this way and based on that, he designed the Beethoven bust. It is still considered as an authentic portrait of the then 42-year-old composer. Today, various replicas of this sculpture have been preserved, most of which were made in the 19th century of plaster or bronze. The original bust was in the possession of Andreas Streicher’s family in Vienna for a long time, until the Historical Museum of Vienna obtained it. In 1890, a cast was made from this original for the Beethoven House in Bonn, which in turn was moulded and re-cast several times Fig. 5; [9].

Conflict of interest

R. Sedivy declares that he has no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Siebert M. Totenmaske und Porträt. Der Gesichtsabguss in der Kunst der Florentiner Renaissance. Baden-Baden: Tectum; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruff JR. Violence in early modern europe 1500–1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001. p. 164. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spooner JL. History of surgical face masks. AORN J. 1967;5(1):76–80. doi: 10.1016/S0001-2092(08)71359-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolfgang R, Michael N. Franz Joseph Gall und seine „sprechenden Schedel“ schufen die Grundlagen der modernen Neurowissenschaften. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2008;158:314–319. doi: 10.1007/s10354-008-0540-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maurer R. Die Schädelsammlung Dr. Galls im Rollettmuseum Baden bei Wien Franz Josef Gall (1758–1828) Wien Med Wochenschr. 2008;158:339–351. doi: 10.1007/s10354-008-0543-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ariés P. Geschichte des Todes. München: dtv; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perpinya N. Ruins, nostalgia and ugliness. Five romantic perceptions of middle ages and a spoon of game of thrones and avant-garde oddity. Berlin: Logos; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landenburger M, Bettermann S, editors. Drei Begräbnisse und ein Todesfall. Beethovens Ende und die Erinnerungskultur seiner Zeit. Bonn: Beethoven-Haus; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beethoven-Haus Bonn. Website. 2021. www.beethoven.de. Accessed 9 Mar 2021.