Abstract

Objective:

The field of neuropsychology’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic was characterized by a rapid change in clinical practice secondary to physical distancing policies and orders. The current study aimed to further characterize the change in neuropsychologists’ professional practice, specifically related to teleneuropsychology (TNP) service provision, and also provide novel data regarding the impact of the pandemic on providers’ emotional health.

Method:

This study surveyed 142 neuropsychologists between 3/30/2020 and 4/10/2020, who worked within a variety of settings (e.g., academic medical centers, general hospitals, Veterans Affairs medical centers, rehabilitation hospitals) across all four U.S. geographic regions. Mixed-model analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted to assess for differences in neuropsychological practice (i.e., total number of patients and proportion of TNP seen per week) across time points (i.e., late February and early April) by practice setting and region. Descriptive statistics were conducted to describe respondents’ perceptions of TNP, emotional responses to the pandemic, and perceptions of institutional/employers’/practices’ responses.

Results:

Nearly all respondents (~98%) reported making practice alterations, with ~73% providing at least some TNP. Neuropsychologists across all settings and regions reported performing a higher proportion of TNP evaluations by April 2020. On average, respondents reported a medium amount of distress/anxiety related to COVID-19, which had a “somewhat small impact” on their ability to practice overall.

Conclusions:

The current study further elucidated neuropsychologists’ provision of TNP services and offered initial data related to their emotional response to the pandemic. Future research is needed to examine the viability and sustainability of TNP practice.

Keywords: teleneuropsychology, clinical practice, mental health, COVID-19

Introduction

The standardization and validation of teleneuropsychology (TNP) has evolved in recent years (Brearly et al., 2017; Joint Task Force for the Development of Telepsychology Guidelines for Psychologists, 2013; Marra, Hamlet, Bauer, et al., 2020a), and the context of COVID-19 and its associated physical distancing policies have necessitated the widespread adoption of TNP. While the shift to TNP is critical during a pandemic to ensure that neuropsychological services can be provided to those in need, it comes with new challenges and concerns. Fortunately, the field of neuropsychology’s response to the pandemic was characterized by timely symposia, webinars, and guidelines to assist neuropsychologists in effectively executing the transition to TNP (Cullum et al., 2020; Stolwyk, Hammers, Harder, & Cullum et al., 2020). While recent surveys provided initial data about neuropsychologists’ response to TNP adoption, the ever-changing impacts of COVID-19 on clinical practice and providers’ mental health remain to be established. In addition, differences in responses related to characteristics such as practice settings and geographic locations would provide insight into how various providers may be handling this transition differently. Such information is critical for our field to continue to grow and expand our TNP toolset, even beyond the context of COVID-19.

The first survey following the pandemic was distributed by the American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology (https://theaacn.org/aacn-covid-19-survey/) between March 23 and March 26, 2020 which was 12 to 15 days after the pandemic was declared by the World Health Organization (2020). At that time, nearly 80% of the 372 respondents, who primarily worked in private practice and medical centers, indicated a halt of in-person neuropsychological assessment, and approximately 67% either were conducting TNP services or planned to do so in the future. In addition, while the majority of respondents “offered” or “would offer” interviews (~73%) and/or feedbacks (~66%), a much smaller portion of providers reported offering full evaluations (~30%). Part of the hesitance in pursuing TNP for full evaluations seemed to stem from a lack of knowledge, given that ~43% of respondents requested clear guidance on TNP practice. In response to these findings, on July 16, 2020 Bilder et al. (2020) from the Inter Organizational Practice Committee (IOPC) published an all-inclusive resource of provisional guidance on implementing TNP services to promote continuity of care and services. The article advised clinicians who are conducting TNP or considering its adoption to develop necessary procedural changes (e.g., informed consent, report modifications) and to be aware and state the inherent limitations of TNP when appropriate (e.g., diagnostic conclusions and recommendations, specific patient populations or diversity factors, certain referral questions).

Shortly after these provisions, several case series also illustrated particular considerations for novel TNP service models when working with pediatric populations (Peterson, Ludwig, & Jashar, 2020; Pritchard et al., 2020), patients across the lifespan (Hewitt et al., 2020), and specific neurological populations, such as individuals referred for pre-surgical evaluations (Hewitt & Loring, 2020). Together, these studies offered practical implications and recommendations for neuropsychologists as they transitioned to TNP, including 1) explicit scripts for TNP informed consent practices and reporting results of TNP evaluations, 2) tips for conducting interviews and feedbacks to develop rapport (e.g., normalizing the difficulties with technology), and 3) a step-by-step process for conducting a full TNP evaluation. For a comprehensive list of TNP research, please see the IOPC Neuropsychology Toolkit (iopc.squarespace.com/teleneuropsychology-research).

Surveys that were distributed in late March 2020 and compiled data from over 200 neuropsychologists indicated that respondents primarily transitioned to TNP for intakes and feedbacks (51%), with only 14% conducting some testing, and 3% conducting full TNP evaluations (Marra, Hoelzle, Davis, et al., 2020b). Examining differences by setting revealed that while neuropsychologists in private practice appeared to be more acutely affected by the pandemic, in terms of reduced work/pay or being temporarily unpaid compared to those in medical hospitals, there was no difference in TNP practice patterns. Another survey conducted by Hammers and colleagues (2020) was the first to document self-reported baseline (i.e., pre-COVID-19) percentages of TNP practices among a group of international neuropsychologists, as well as a smaller proportion of non-neuropsychologists, who attended a no-cost global webinar related to practical/ethical considerations of TNP practice on April 2, 2020. Respondents represented five continents (i.e., North America, Europe, Asia/Southeast Asia, South America, Australia) and consisted of a large sample (estimates that n = 597 to 1,074). Results indicated that prior to the pandemic, approximately one-quarter of the sample used TNP for clinical interviews, feedback, and intervention, whereas only one-tenth used TNP for test administration. In the context of COVID-19, although there was a clear increase in TNP use for interviews, feedback, and intervention, test administration via TNP remained largely unchanged.

Together, these surveys described providers’ intuitive and necessary shift to TNP since the onset of COVID-19; however, several questions remain. First, the AACN survey did not clearly differentiate which providers were in fact providing TNP at that time versus those who planned to provide TNP in the future. Moreover, both the AACN survey and Marra, Hoelzle, Davis, et al. (2020b) did not compare pre-COVID-19 practice habits (e.g., use of TNP) to providers’ current usage rates. While Hammers and colleagues (2020) surveyed pre-COVID-19 TNP use, the authors acknowledged that their results could have been inadvertently influenced by the fact that a proportion of respondents were students and/or non-neuropsychologists. As such, there remains a call to describe and differentiate in more precise detail potential differences in neuropsychologists’ practice adjustments across a wider variety of practice settings (Marra, Hoelzle, Davis, et al., 2020b). Previous surveys also highlighted clinicians’ concerns about or discomfort with implementing TNP due to the possible breach of ethical practice (Hammers et al., 2020; Marra, Hoelzle, Davis, et al., 2020b). Low knowledge and confidence about TNP, as well as concern about clinician and patient access to required technology, were cited as additional reasons for low uptake in a sample of Australian neuropsychologists prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (Chapman et al., 2020); however, there were also positive perceptions of TNP related to increased convenience for both clinicians and patients, and the possibility of expanding service delivery. However, there again remains a gap in the literature regarding U.S. neuropsychologists’ perceptions of TNP, access to technology services, and emotional response to the pandemic on both personal and professional levels.

The present study aimed to contribute to the existing TNP literature base by further describing neuropsychologists’ practice adjustments during and emotional response to the evolving COVID-19 pandemic. The primary objective was characterizing the changes in clinical practice from February 2020 to April 2020. First, we compared the total number of patients (i.e., combined in-person and TNP) and then examined the proportion of TNP patients seen (i.e., number of TNP cases divided by total number of patients seen). These analyses were conducted in order to address the concerns of a subset of clinicians, predominantly those in private practice, who reported being acutely affected by the pandemic (Marra, Hoelzle, Davis, et al., 2020b). The authors hypothesized that providers’ transition in response to the pandemic and uptake of TNP would vary depending on 1) practice setting and 2) geographic region, given the differential “spikes” in COVID-19 cases across the United States. However given the lack of TNP literature examining the impact of neuropsychologists’ practice setting and geographic region, these analyses were exploratory. Our second objective was to illustrate neuropsychologists’ perceptions of TNP, how well they perceived their respective institution/employer/practice had responded to COVID-19, and their own emotional responses to the global pandemic.

Methods

Data collection

Data for the current study, which focuses on neuropsychologists, were derived from a larger study (Reilly et al., 2020) investigating the immediate responses to COVID-19 of mental health practitioners broadly. Regulatory approval was received by the Institutional Review Board of the coauthors’ university. The population of interest was adults (i.e., those 18 years of age or older) fluent in reading English who were currently working in a behavioral/mental health field, including neuropsychologists. This included both trainees and licensed practitioners. Of note, the current study includes only non-trainee neuropsychologists (as described in the “Analytic Sample” section below). The sampling frame for the non-probability sample (Marcopulos et al., 2020) included individuals on various relevant professional listservs (e.g., American Psychological Association, National Academy of Neuropsychology), departmental listservs, indirect recruitment through emails to colleagues, and open advertisement of the study to relevant individuals on social media platforms. Respondents could submit the survey anonymously or confidentially by providing their email. The recruitment email included a request for participants to forward the email to fellow colleagues if willing (i.e., snowball sampling). This method and, more generally, non-probability sampling were used to recruit as many individuals as possible given the urgency of understanding how mental health practitioners were responding to this public health crisis. Reminders and incentives were not used to enhance survey response. It is difficult to discern a true response rate (e.g., Hammers et al., 2020; Marra et al., 2020; Sweet et al., 2015) given that the electronic invitation was likely forwarded to others as we specifically requested respondents to do so. As such, we used AACN 2019 membership data, excluding student affiliates (Morrison, 2020) to provide the best estimate for this non-probability sampling technique (~7.8%), though this is likely an overestimate.

Using Qualtrics Survey Software, we distributed a 46-item questionnaire via an email link. The survey was created based on face-valid questions that were deemed clinically relevant by the coauthors. Although the survey did not include established, validated measures, survey questions were piloted and feedback was sought from a variety of mental health providers (e.g., psychologists, neuropsychologists, social workers, psychiatrists). Respondents were asked to estimate the number of patients they saw weekly retrospectively (i.e., end of February) and at present (i.e., late March/early April 2020). Responses were based on self-report and were not verified by any objective markers (e.g., billing sheets). Respondents completed the survey during a 12-day period (i.e., 3/30/2020 – 4/10/2020). Data obtained consisted of respondents’ demographics, information pertaining to work-related patient populations and caseload, practice adjustments in response to COVID-19, perceptions of TNP, and emotional responses to the pandemic. All questions were optional, and no incentives were offered. See the Appendix for the survey in its entirety.

Analytic sample

Participants were selected from a larger study sample that investigated mental health practitioners’ immediate response to COVID-19. Inclusion criteria for the current sample included respondents who 1) were employed as a licensed clinical neuropsychologist and 2) resided in the United States. Exclusion criteria included those who identified as a “trainee,” as the purpose of this study was intended to characterize professional practice adjustment. A small portion of respondents were removed due to missing or incomplete data (n = 6). A Qualtrics feature that prevented “ballot box stuffing” verified that each respondent completed the survey only once.

The final analytic sample consisted of 142 neuropsychologists. The majority (~59%) of respondents were recruited through professional and departmental listservs, with smaller proportions recruited through personal emails (~23%), and social media (16%). Respondents were predominantly White (90.6%) and women (78.2%), with a mean age of 42.1 years (SD = 9.8, range = 28-72). No demographic differences in age, gender, or race/ethnicity were noted across settings (p values > .05). The current sample was comparable to the greater population of neuropsychologists working in the United States in terms of age, race/ethnicity, patient populations, and geographic distribution for the Northeast (~17% in this sample versus 23%) and West (~23% in this sample versus 16%; Sweet et al., 2015). In contrast, our sample consisted of a greater number of female neuropsychologists (~78% versus ~56%) and respondents in the South (~40% in this sample versus ~30%), as well as a lower number of respondents in the Midwest (~19% in this sample versus 31%; Sweet et al., 2015). Regarding employment status, the majority of respondents in this study worked fulltime (90.1%), with a small subset working part-time (9.9%). Providers typically conducted services across multiple patient settings (e.g., both inpatient and outpatient), with ~36% working exclusively within an outpatient setting and only ~4% working exclusively within an inpatient setting. In addition, the majority of respondents identified their patient population as adults (including older adults; ~61%), while ~30% reported providing services across the lifespan and ~9% evaluated pediatric patients exclusively. While a complete comparison of the current samples’ work setting to the greater population was difficult to determine due to differences in how these data were obtained and reported, the number of respondents working in a private practice setting was comparable to the greater population (~25% in this sample versus ~22%; Sweet et al., 2015).

Data analyses

Participant data were analyzed in SPSS Version 26 following extraction from the Qualtrics Survey Software. We conducted descriptive analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and chi-square analyses to determine differences in demographic variables across participant work settings (i.e., academic medical centers, general hospitals, rehabilitation hospitals, Veterans Affairs medical center, private practice, multiple settings). We then investigated the total number of patients seen weekly in person and remotely in February 2020 and late March/early April (i.e., 3/30/2020 – 4/10/2020), as well as the proportion of TNP patients seen weekly at those two time points, both for the full sample and by setting (ANOVA).

A Time × Setting mixed-model ANOVA was run with the dependent variable being the total number of weekly patients seen (i.e., in-person and remote combined) and the independent variables being participants’ work setting (i.e., academic medical center, general hospital, rehabilitation hospital, Veterans Affairs medical center, private practice, multiple settings) and the two time points (i.e., late February 2020 and late March through early April 2020). All dependent variables were logarithmically transformed due to heavily positive skews. A second Time × Setting mixed-model ANOVA was conducted with the dependent variable being the proportion of patients seen through TNP (i.e., TNP divided by total number of patients seen) and the independent variables being participants’ work setting and time point.

We then examined the impact of regional location on practice methods across the two time periods (i.e., late February and late March through early April) regardless of setting, by dividing regions in concordance with the United States Census Bureau’s method (i.e., Northeast, South, Midwest, and West; United States Census Bureau, 2018). We ran a Time × Region mixed-model ANOVA, first with the total number of patients seen and then again with the proportion of TNP patients, mirroring the prior analyses.

Additional descriptive analyses were conducted to illustrate neuropsychologists’ service delivery (responses were not mutually exclusive), emotional responses to the pandemic (i.e., level of COVID-19-related anxiety/distress), and their views of their respective work settings’ response to the pandemic. For questions related to neuropsychologists’ emotional response, respondents used a sliding scale (0-10) to rate their level of distress/anxiety, with a higher number indicating greater distress/anxiety. Questions related to the emotional impact on services were based on a 5-point Likert scale (i.e., 1 = “no impact” to 5 = “very large impact”). The remaining questions pertaining to the institutional response to the pandemic were also on a 5-point Likert scale (i.e., 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

Results

Participant demographics and professional practice

Table 1 details the demographic characteristics for the entire sample (n = 142) and disaggregated by setting. The majority of respondents were located in the South (40.3%). Chi-square analysis confirmed that the proportion of respondents significantly differed across settings in different regions (p = .01). While post-hoc analyses were not conducted due to the number of levels involved, descriptive inspection suggested that a large number of respondents from Veterans Affairs medical centers (VAMC; 66.7%) and multiple practice settings (40.0%) were in the South, whereas the majority of those in rehabilitation hospitals (47.1%) were in the Northeast.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics.

| Total Sample | Academic Medical Center |

General Hospital |

Private Practice |

Rehabilitation Hospital |

Veterans Affairs Medical Center |

Multiple Settings |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 142 (100.0%) | 33 (23.2%) | 20 (14.1%) | 35 (24.6%) | 17 (12.0%) | 17 (12.0%) | 20 (14.1%) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 42.1 (9.8) | 42.4 (10.3) | 41.3 (8.9) | 44.4 (11.3) | 40.4 (9.7) | 42.1 (9.1) | 40.0 (7.6) |

| Female, n (%) | 111 (78.2%) | 27 (81.8%) | 19 (95.0%) | 29 (82.9%) | 12 (70.6%) | 12 (70.6%) | 12 (60%) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||||||

| Asian | 3 (2.2%) | 1 (3.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.0%) |

| Black | 2 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.9%) | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| White | 126 (90.6%) | 29 (90.6%) | 19 (95.0%) | 31 (88.6%) | 15 (88.2%) | 13 (86.7%) | 19 (95.0%) |

| Hispanic | 5 (3.6%) | 2 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (5.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Multiracial | 3 (2.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.0%) | 2 (5.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Region, n (%) | |||||||

| Northeast | 24 (17.3%) | 5 (15.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (20.0%) | 8 (47.1%) | 1 (6.7%) | 3 (15.0%) |

| South | 56 (40.3%) | 13 (40.6%) | 7 (35.0%) | 13 (37.1%) | 5 (29.4%) | 10 (66.7%) | 8 (40.0%) |

| Midwest | 27 (19.4%) | 11 (34.4%) | 6 (30.0%) | 4 (11.4%) | 1 (5.9%) | 3 (20.0%) | 2 (10.0%) |

| West | 32 (23.0%) | 3 (9.4%) | 7 (35.0%) | 11 (31.4%) | 3 (17.6%) | 1 (6.7%) | 7 (35.0%) |

Note. N = 142.

Response to COVID-19: Practice adjustments and service delivery

When asked about practice adjustments related to COVID-19, nearly all respondents (97.9%) reported making alterations in practice. Specifically, more than 80% of respondents indicated working some percentage of time remotely, with nearly half of the respondents working 60% or more of the week in a remote setting. In terms of scheduling/providing patient services, ~40% of respondents were cancelling appointments, ~80% were rescheduling patients to a later date, and ~25% were restricting in-person appointments to certain patient populations. For those who were rescheduling patients, nearly 25% indicated rescheduling patients “indefinitely.”

In terms of TNP service delivery, while 88% of respondents did not offer TNP in February 2020, by late March/early April, the majority of respondents (~73%) were offering some form of TNP services. See Tables 2 and 3 for a breakdown of practice adjustments and service delivery by setting and region. Specifically, ~47% provided virtual interviews only, ~19% offered inpatient/consult services, and ~18% conducted entire TNP evaluations. In contrast, ~19% of respondents continued to provide in-person neuropsychological evaluations, ~4% limited in-person services to interviews only, and ~27% indicated not offering any services because of the pandemic.

Table 2.

Delivery of services by practice setting.

| Total Sample (n = 142) |

Academic Medical Center (n = 33) |

General Hospital (n = 20) |

Private Practice (n = 35) |

Rehabilitation Hospital (n = 17) |

Veterans Affairs Medical Center (n = 17) |

Multiple Settings (n = 20) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients Seen Weekly, M (SD) | |||||||

| February 2020 | |||||||

| In person | 9.5 (8.0) | 8.9 (5.3) | 9.2 (7.9) | 9.5 (8.2) | 15.9 (13.2) | 6.2 (4.3) | 8.0 (5.4) |

| TNP | 0.3 (1.7) | 0.2 (0.7) | 0.1 (0.4) | 0.1 (0.7) | 1.3 (4.4) | 0.5 (0.9) | 0.3 (1.1) |

| Proportion TNP | .03 (.09) | .01 (.05) | .01 (.05) | .01 (.03) | .07 (.17) | .07 (.14) | .03 (.12) |

| April 2020 | |||||||

| In person | 2.8 (6.3) | 2.1 (4.6) | 1.5 (4.1) | 2.3 (6.2) | 10.0 (11.3) | 1.2 (2.3) | 1.1 (2.2) |

| TNP | 3.2 (4.9) | 2.4 (3.8) | 2.5 (4.1) | 2.9 (4.4) | 5.7 (9.8) | 4.0 (3.2) | 2.8 (3.0) |

| Proportion TNP | .47 (.46) | .40 (.45) | .40 (.50) | .51 (.46) | .25 (.35) | .78 (.37) | .53 (.48) |

| Service Delivery, n (%) | |||||||

| No current services | 38 (27.1%) | 11 (33.3%) | 9 (45.0%) | 11 (32.4%) | 1 (6.3%) | 2 (11.8%) | 4 (20.0%) |

| Inpatient/consult services | 29 (19.3%) | 7 (21.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (68.8%) | 5 (29.4%) | 4 (20.0%) |

| Teleneuropsychology | |||||||

| Interview Only | 66 (47.1%) | 17 (51.5%) | 9 (45.0%) | 16 (47.1%) | 3 (18.8%) | 10 (58.8%) | 11 (55.5%) |

| Full Evaluation | 25 (17.9%) | 3 (9.1%) | 1 (5.0%) | 4 (11.8%) | 3 (18.8%) | 9 (52.9%) | 5 (25.0%) |

| In-Person | |||||||

| Interview Only | 5 (3.6%) | 1 (3.0%) | 1 (5.0%) | 2 (5.9%) | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Full Evaluation | 26 (18.6%) | 2 (6.1%) | 3 (15.0) | 6 (17.6%) | 8 (50.0%) | 3 (17.6%) | 4 (20.0%) |

Note. N = 142; TNP = teleneuropsychology; data under the patients seen weekly were un-transformed raw scores and standard deviations provided by respondents.

Note. Service delivery for data compiled between 3/30/20-4/10/20. Service delivery types were not mutually exclusive (i.e., respondents could select all that applied for their current practices).

Table 3.

Delivery of services by geographic region.

| Total Sample (N = 139) |

Northeast (n = 24) |

South (n = 56) |

Midwest (n = 27) |

West (n = 21) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients seen weekly, M (SD) | |||||

| February 2020 | |||||

| In person | 9.4 (8.5) | 10.7 (9.2) | 9.8 (9.8) | 8.2 (4.6) | 8.0 (7.2) |

| TNP | 0.4 (2.0) | 1.3 (3.7) | 0.1 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.9) | 0.1 (0.3) |

| Proportion TNP | .03 (.09) | .10 (.16) | .02 (.08) | .02 (.06) | .01 (.05) |

| April 2020 | |||||

| In person | 2.8 (6.3) | 4.7 (6.6) | 3.0 (8.0) | 1.3 (3.6) | 2.0 (4.3) |

| TNP | 3.2 (5.0) | 5.5 (9.0) | 2.7 (3.5) | 2.2 (2.9) | 3.4 (4.1) |

| Proportion TNP | .47 (.46) | .39 (.41) | .46 (.48) | .53 (.49) | .50 (.44) |

| Service delivery, n (%) | |||||

| No current services | 38 (27.7%) | 5 (21.7%) | 19 (33.9%) | 8 (29.6%) | 6 (19.4%) |

| Inpatient/consult services | 26 (19.0%) | 7 (30.4) | 8 (14.3%) | 5 (18.5%) | 6 (19.4%) |

| Teleneuropsychology | |||||

| Interview Only | 64 (46.7%) | 12 (52.2%) | 19 (33.9%) | 14 (51.9%) | 19 (61.3%) |

| Full Evaluations | 25 (18.2%) | 7 (30.4%) | 11 (19.6%) | 2 (7.4%) | 5 (16.1%) |

| In-person | |||||

| Interview Only | 5 (3.6%) | 2 (8.7%) | 2 (3.6%) | 1 (3.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Full Evaluations | 26 (19.0%) | 6 (26.1%) | 8 (14.3%) | 5 (18.5) | 7 (22.6%) |

Note. N = 139; TNP = teleneuropsychology; data under the patients seen weekly were un-transformed raw scores and standard deviations provided by respondents.

Note. Service delivery data compiled between 3/30/20-4/10/20. Service delivery types were not mutually exclusive (i.e., respondents could select all that applied for their current practices).

A subset of the respondents (n = 26) specified in an open-response format which neuropsychological measures they were incorporating in their TNP evaluations. The most commonly administered tests included mental status exams (e.g., Blind Montreal Cognitive Assessment [MoCA-Blind]; modified Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE]; Wechsler Memory Scale [WMS]-3rd Edition-Mental Control; Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status [TICS]; Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status [RBANS]); processing speed (e.g., Oral Trail Making Test; Oral Digit Symbol Substitution); attention/working memory (e.g., Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-4th Edition [WAIS-IV] - Digit Span, Arithmetic, Letter-Number Sequencing subtests); language (e.g., aspects of the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination [BDAE]; WAIS-IV Vocabulary, Information subtests; Semantic Fluency; Boston Naming Test- Long and Short Form; Verbal Naming Test); verbal memory (e.g., California Verbal Learning Test [CVLT] -2nd Edition, Hopkins Verbal Learning Test [HVLT]; WMS-IV Logical Memory); visual memory (e.g., Benton Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised [BVMT-R]; Rey-Complex Figure Test [RCFT]); executive functioning (e.g., Controlled Oral Word Association Test, Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System [DKEFS]- Verbal Fluency subtest; Test of Practical Judgment [TOP-J], Neuropsychological Assessment Battery [NAB] - Judgment, Proverbs, and Color-Word Interference subtests; Clock Drawing; Independent Living Scales-Health and Safety subtest); estimate of premorbid abilities (e.g., Test of Premorbid Functioning [TOPF]; Hopkins Adult Reading Test, Wechsler Test of Adult Reading [WTAR], Wide Range Achievement Test [WRAT] – 4th edition -Word Reading subtest); task engagement (e.g., Reliable Digit Span, Oral Word Memory Test); and mood (e.g., Geriatric Depression Scale [GDS]; General Anxiety Disorder-7 [GAD-7]; Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ]).

Group differences in TNP implementation

In order to identify potential differences between practice settings, we examined the estimated number of patients seen weekly evaluated at the two time points (i.e., February and late March/early April 2020). Table 2 details the estimated number of patients seen weekly at each time point across the settings, as well as the proportion seen via TNP. In February 2020, on average neuropsychologists in most settings saw fewer than one patient per week via TNP, with rehabilitation hospitals as a notable exception.

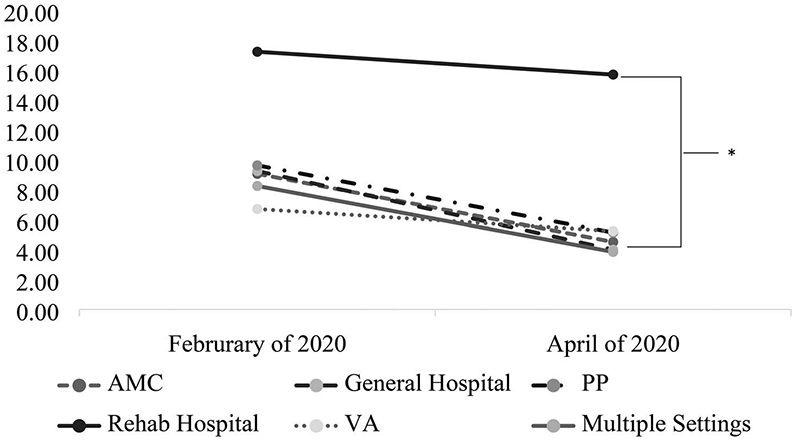

A Time × Setting mixed-model ANOVA identified main effects for time, F(1, 136) = 59.3, p < .01, partial η2 = .30, and setting, F(5, 136) = 5.4, p < .01, partial η2 = .17, for the total number of patients seen (i.e., in-person and TNP combined). No interaction effects were identified (p = .11). Post-hoc Bonferroni tests indicated that rehabilitation hospitals saw more patients than the other five settings (p < .01). Overall, fewer patients were seen in late March/early April 2020 (M = 9.8, SD = 8.3) compared to February 2020 (M = 5.9, SD = 8.5, p < .01). See Figure 1.

Figure 1. Total patients seen by February 2020 and April 2020 across settings.

Note. N = 142; AMC = Academic Medical Center; PP = private practice; VA = Veterans Affairs medical center; Rehab = rehabilitation; *p < 0.01 when comparing rehabilitation hospitals to all other settings.

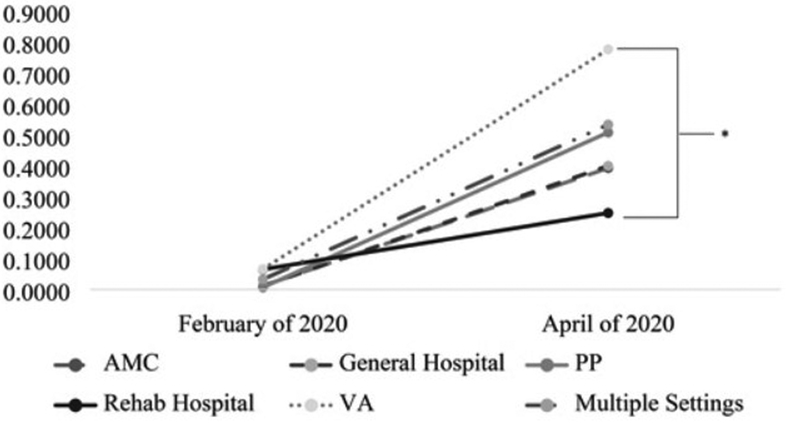

Next, a Time x Setting mixed-model ANOVA examined the proportion of TNP cases. Again, main effects for time, F(1, 136) = 127.8, p < .01, partial η2 = .48, and setting, F(5, 136) = 3.02, p = .01, partial η2 = .10, were identified. Post-hoc Bonferroni analyses indicated that VAMCs overall saw a higher proportion of TNP cases than rehabilitation hospitals or academic medical centers. As expected, a higher proportion of patients was seen through TNP in late March/early April 2020 compared to February 2020. In addition, an interaction effect was identified, F(5, 136) = 2.7, p = .02, partial η2 = .10. Follow-up tests of simple effects with Bonferroni corrections indicate that VAMCs saw a greater proportion of TNP patients compared to rehabilitation settings by late March/early April 2020 (p < .01). See Figure 2.

Figure 2. Proportion of teleneuropsychology patients seen by February 2020 and April 2020 across settings.

Note. N = 142; AMC = Academic Medical Center; PP = private practice; VA = Veterans Affairs medical center; Rehab = rehabilitation; *p < 0.01.

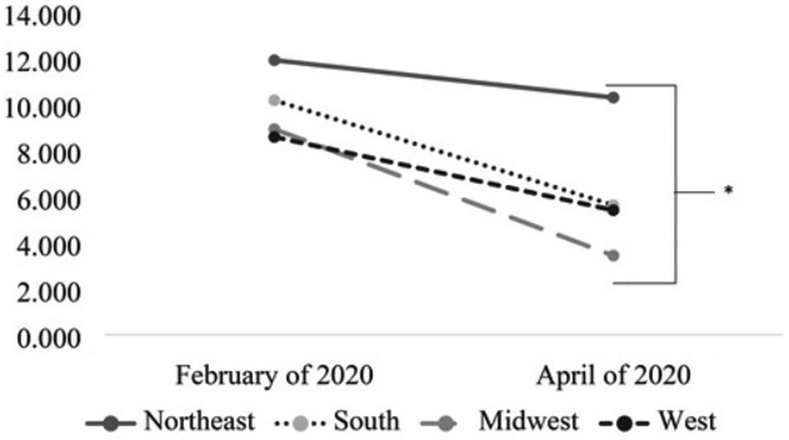

In order to determine potential geographic differences in practice, we divided regions per the U.S. Census Bureau’s method to conduct a Time x Region analysis. Table 3 details the estimated number of patients seen at each time point across the regions, along with the proportion of TNP cases. For the total number of patients seen, a mixed-model ANOVA found a main effect for Time, F(1, 135) = 59.7, p < .01, partial η2 = .31, but not for Region (p = .14). A Time x Region interaction effect was identified, F(1, 135) = 2.7, p = .04, partial η2 = .10. Bonferroni tests of simple effects indicated that by late March/early April 2020, Neuropsychologists in the Northeast saw more patients overall than those in the Midwest (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Total patients seen by February 2020 and April 2020 across regions.

Note. N = 142; *p < 0.01.

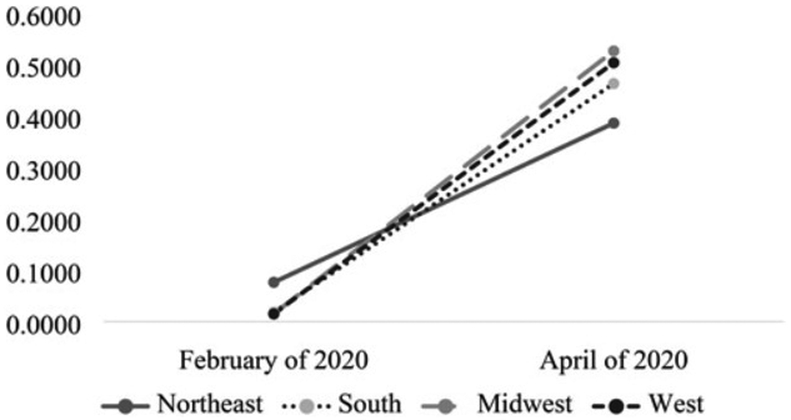

Finally, the Time x Region analysis was repeated with the proportion of TNP patients as the dependent variable. A main effect for Time was identified, F(1, 135) = 112.3, p < .01, partial η2 = .45, such that a greater proportion of patients was seen through TNP in late March/early April 2020 compared to late February 2020. The main effect for Region (p = .92) and the interaction effect (p = .41) were not significant. See Figure 4 for the plot.

Figure 4. Proportion of teleneuropsychology patients seen by February 2020 and April 2020 across regions.

Note. N = 142.

Neuropsychologists’ perceptions of TNP and emotional response to COVID-19

Despite more than three-quarters of the sample (~79%) having easy access to information technologies (IT) staff and services, only ~20% of providers found the implementation of TNP to be “very easy” or “somewhat easy,” and roughly 48% perceived TNP implementation as “somewhat difficult” or “very difficult.” Nonetheless, more than half of the respondents (56%) perceived their respective institution/employer/practice as having provided adequate information and training related to telehealth, and a similar percentage (~51%) indicated being “somewhat likely” or “very likely” to continue to provide some form of TNP services in the future.

Our final descriptive analyses were aimed at understanding neuropsychologists’ emotional response to COVID-19 and their perceptions of how their institution/employer/practice responded. Please see Tables 4 and 5 for the median (Mds) and interquartile ranges (IQR; 25th - 75th percentiles) for the total sample and disaggregated by setting and geographic region.

Table 4.

Emotional response to COVID-19 and perceptions of institutional response by practice setting.

| Mds (IQR) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample (n = 136) |

Academic Medical Center (n = 33) |

General Hospital (n = 19) |

Private Practice (n = 34) |

Rehabilitation Hospital (n = 15) |

Veterans Affairs Medical Center (n = 15) |

Multiple Settings (n = 19) |

|

| Emotional response (0 – 10 scale) | |||||||

| 1. Overall distress/anxiety (n = 136) | 6.0 (4.0– 7.0) | 6.0 (3.5– 7.5) | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | 7.0 (4.5–7.0) | 6.0 (4.0–8.0) | 5.5 (4.0–6.8) | 5.0 (2.0–7.0) |

| 2. Distress/anxiety about societal impacts (e.g., mental health, capacity of healthcare system to accommodate affected individuals, the economy; n = 136) | 7.0 (5.0–8.8) | 7.0 (6.0–9.0) | 7.0 (5.0–8.0) | 7.0 (5.0–8.0) | 8.0 (7.0–9.0) | 6.5 (4.3–8.8) | 7.0 (6.0–9.0) |

| 3. Distress/anxiety that you or someone you know will contract COVID-19 (n = 136) | 6.0 (4.0–8.0) | 6.0 (5.0–8.0) | 6.0 (5.0–7.0) | 7.0 (4.8–8.0) | 8.0 (6.0–9.0) | 6.0 (3.0–7.0) | 5.0 (3.0–8.0) |

| 4. Distress related to caregiving during COVID-19 (n = 50) | 6.0 (4.8–9.0) | 6.0 (2.5–8.5) | 6.0 (6.0–8.0) | 7.0 (3.5–7.0) | 10.0 (6.0–10.0) | 6.5 (4.8–7.5) | 6.0 (5.0–9.3) |

| Emotional impact (1 – 5 scale) | |||||||

| 5. How much has your distress/ anxiety related to COVID-19 impacted your ability to provide services (n = 113) | 4.0 (2.0–4.0) | 3.0 (3.0–4.0) | 4.0 (2.0–4.0) | 3.0 (1.0–4.0) | 4.0 (3.0–4.0) | 3.0 (2.3–4.0) | 4.0 (3.0–4.0) |

| “My institution/employer/practice…” (1 – 5 scale) | |||||||

| 6. …was adequately prepared to address concerns/changes arising from COVID-19” (n = 134) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 4.0 (1.8–4.0) | 3.0 (2.0–5.0) | 4.0 (3.0–4.0) | 2.0 (1.0–3.8) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) |

| 7. …is responding appropriately to COVID-19” (n = 134) | 4.0 (2.0–5.0) | 4.0 (4.0–5.0) | 4.0 (2.0–4.25) | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) | 4.0 (2.0–5.0) | 3.5 (2.0–5.0) | 4.0 (2.0–5.0) |

| 8. …is providing a safe working environment during COVID-19” (n = 136) | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | 4.0 (1.8–4.0) | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) | 4.0 (2.0–4.0) | 2.0 (2.0–4.8) | 4.0 (2.0–5.0) |

Note. Questions 1–4: respondents selected a number (i.e., sliding scale from 0–10, higher number = more anxiety/distress); Question 5: scale based on 1–5 where 1 = no impact, 2= very small impact, 3 = somewhat small impact, 4 = somewhat large impact, 5 = very large impact; Questions 6–8: respondents selected, 1 = strongly disagree, 2= somewhat disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = somewhat agree, 5 = strongly agree.

Table 5.

Emotional Response to COVID-19 and Perceptions of Institutional Response by Geographic Region.

| Mds (IQR) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 133) |

Northeast (n = 22) |

South (n = 54) |

Midwest (n = 26) |

West (n = 31) | |

| Emotional response (0 – 10 scale) | |||||

| 1. Overall distress/anxiety (n = 133) | 6.0 (4.0–7.0) | 7.0 (6.0–8.0) | 5.0 (3.0–7.0) | 5.5 (4.0–8.0) | 6.0 (3.0–7.0) |

| 2. Distress/anxiety about societal impacts (e.g., related to mental health, capacity of healthcare system to accommodate affected individuals, the economy; n = 133) | 7.0 (5.0–8.5) | 8.0 (6.0–9.0) | 7.0 (5.0–8.3) | 8.0 (5.0–9.0) | 7.0 (5.0–8.0) |

| 3. Distress/anxiety that you or someone you know will contract COVID-19 (n = 133) | 6.0 (4.0–8.0) | 7.5 (6.0–10.0) | 6.0 (3.0–8.0) | 6.0 (5.0–7.3) | 5.0 (3.0–8.0) |

| 4. Distress related to caregiving during COVID-19 (n = 50) | 6.0 (4.8–9.0) | 9.0 (5.8–10.0) | 6.0 (3.5–8.0) | 6.5 (3.8–7.8) | 6.0 (5.0–7.0) |

| Emotional impact (1 – 5 scale) | |||||

| 4. How much has your anxiety/distress related to COVID-19 impacted your ability to provide services (n = 113) | 4.0 (2.0–4.0) | 4.0 (3.0–4.0) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 3.0 (3.0–4.0) | 4.0 (3.0–4.0) |

| “My institution/employer/practice…” (1 – 5 scale) | |||||

| 5. was adequately prepared to address concerns/changes arising from COVID-19” (n = 133) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 3.0 (1.8–4.3) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 4.0 (2.0–4.0) |

| 6. is responding appropriately to COVID-19” (n = 133) | 4.0 (2.0–5.0) | 5.0 (2.0–5.0) | 4.0 (2.0–5.0) | 4.0 (4.0–5.0) | 4.0 (2.8–5.0) |

| 7. is providing a safe working environment during COVID-19” (n = 133) | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | 4.0 (2.0–5.0) | 4.0 (2.5–5.0) | 4.0 (2.0–4.3) | 4.5 (3.0–5.0) |

Note. Questions 1–4: respondents selected a number (i.e., sliding scale from 0–10, higher number = more anxiety/distress); Question 5: scale based on 1–5 where 1 = no impact, 2 = very small impact, 3 = somewhat small impact, 4 = somewhat large impact, 5 = very large impact; Questions 6–8: respondents selected, 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = somewhat disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = somewhat agree, 5 = strongly agree.

Qualitatively, responses indicated varying levels of distress/anxiety related to the pandemic, caregiving responsibilities, and the emotional impact on one’s ability to practice. In addition, while more than one-third of respondents (n = 52/142; ~36%) did not perceive their institution/employer/practice as being adequately prepared to address the concerns/changes arising from COVID-19, a higher percentage of respondents (n = 95/142; ~67%) reported that their institution/employer/practice responded appropriately to the pandemic, including the ability to provide a safe working environment (n = 86/142; ~61%).

Discussion

The transition to and implementation of TNP is evolving in light of the circumstances surrounding COVID-19. Prior surveys of neuropsychologists highlighted the intuitive and necessary shift to TNP by providers in the United States and internationally. The current study highlights the utilization of TNP service delivery and various practice adjustments across a range of practice settings and geographic regions. In addition, the current study describes respondents’ perceptions of TNP, as well as their personal and professional responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our results suggested a significant shift from in-person visits to TNP between late February and late March/early April 2020. Specifically, a quarter of respondents stopped seeing patients because of the pandemic, but roughly three-quarters of the sample continued with services and on average saw four virtual assessments and three in-person assessments weekly by April 2020. This was the case for all work settings examined across all four U.S. geographic regions. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the effects of the pandemic resulted in neuropsychologists seeing fewer patients overall (i.e., in-person and TNP combined) by late March/early April compared to February 2020. This finding, however, was less true for rehabilitation settings, who continued to see a high number of patients in-person. This is consistent with rehabilitation settings’ higher case-load at baseline, the typical 0% no-show rate for patients in the hospital, and their common practice of providing ongoing “step-down” services (i.e., brief assessment plus interventional/consultative appointments) while patients remain on the unit (Johnson-Greene, 2018). Nonetheless, in support of our hypotheses, we found that in general, neuropsychologists were seeing a higher percentage of patients through TNP by late March/early April than in late February 2020. Follow-up analyses indicated that neuropsychologists in VAMCs saw a higher proportion of TNP patients relative to those in rehabilitation hospitals as of April 2020, which is consistent with previous research showing VAMCs’ increased uptake of telepsychology broadly (Pierce et al., 2020). Lastly, with regard to our regional analyses, we again found a significant shift in total number of weekly patients by late March/early April across all regions, with the Northeast seeing more patients relative to the Midwest. However, this finding may be influenced by the fact that respondents within the Northeast accounted for nearly 50% of the rehabilitation hospitals, compared to neuropsychologists functioning in a rehabilitation setting within the Midwest (~6%). Even so, all regions were offering a higher proportion of TNP appointments in late March/early April compared to February 2020.

Taken together, these findings reflect an increase in TNP by early April 2020, with nearly three-fourths of our sample providing some form of TNP service, which is generally consistent with prior research (Hammers et al., 2020; Marra, Hoelzle, Davis, et al., 2020b). In addition, our findings suggest that nearly 18% of the sample was offering full TNP evaluations (i.e., interview and testing). This percentage appears to be somewhat higher than prior survey results (Chapman et al., 2020; Hammers et al., 2020; Marra, Hoelzle, Davis, et al., 2020b), although these differences may be due to the variability in language used to assess service delivery and/or the fact that some of the previously published survey data were not exclusively about neuropsychologists. In addition, our respondents reported being less likely to continue to provide some form of TNP services in the future relative to an international sample (Hammers et al., 2020), which again may be due to the fact that prior survey results included providers other thanneuropsychologists.

The final analyses within this paper illustrated neuropsychologists’ distress/anxiety in response to the pandemic. Neuropsychologists’ degree of distress/anxiety appeared to be generally similar regardless of setting and geographic region. Taken together, these findings suggested that while neuropsychologists from this sample were endorsing medium levels of distress/anxiety, their emotional response had a small impact on their ability to provide services. In addition, the current sample of neuropsychologists seemed to report somewhat more distress and anxiety about the societal impact of COVID-19 and personal reasons (i.e., caregiving). These responses come alongside the majority of respondents feeling “neutral” or in agreement with steps taken by their institution/employer/practice.

Limitations

Despite the informative findings, our study was characterized by several limitations. First, while our survey questions were face-valid, they were not derived from validated measures. The data were also based upon self-report and thus may be subject to bias, particularly those questions that asked respondents to estimate the number of patients seen per week in late February. Another set of limitations pertain to our sample. First, while there are strengths in using a snowball sampling technique, our sample size was smaller than prior surveys that captured neuropsychologists’ transition to TNP. The estimated response rate was also likely an overestimation, and thus we cannot generalize our findings to the US. neuropsychologist population. Similarly, our data were likely skewed given the higher number of neuropsychologists employed in the South compared to the general population. Another limitation pertains to our analyses, which may have been underpowered to detect significant findings, particularly in three-way interactions, given small cell sizes. Lastly, we distributed our survey relatively early in the pandemic. Although this does highlight the immediate response, as a result, our data represent a short time frame (i.e., 12 days from initiation to closure); however, date of completion did not show a significant relationship with key study variables.

Implications and future directions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to capture data on the transition of TNP prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic, perceptions of TNP, and emotional responses among a sample of exclusively U.S. neuropsychologists. Our findings support the capability of TNP implementation as a supplemental method for maintaining access to services in the context of a pandemic. This is critical given the ongoing concerns regarding COVID-19 and the possibility of future stay-at-home orders. Future analyses aimed at understanding the longevity of TNP practice, potential strengths and barriers, and the psychological factors associated with neuropsychologists’ transition from in-person to TNP service delivery are essential as the field moves forward in order to modify current practices for optimal future care and service delivery. Similarly, the field of neuropsychology would benefit from a better understanding of the viability of TNP (i.e., comparability of TNP data vs. in-person visits, ability to answer referral questions using TNP data, questions related to reimbursement, and ability to overcome technical issues).

Supplementary Material

Table 6.

Undefined

| Strongly disagree |

Somewhat disagree |

Neutral | Somewhat agree |

Strongly agree |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. | Information and planning to respond to COVID-19 were adequately disseminated to me by my supervisor(s). | |||||

| b. | My supervisor(s) have been responsive to my questions and concerns regarding operational/training changes related to COVID-19. |

Funding

JJM receives support from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award U54GM104942-03. The funding source had no other role other than financial support. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology. (2020). COVID-19 links and resources. https://theaacn.org/covid-19-links-and-resources/

- Bilder RM, Postal KS, Barisa M, Aase DM, Cullum CM, Gillaspy SR, Harder L, Kanter G, Lanca M, Lechuga DM, Morgan JM, Most R, Puente AE, Salinas CM, & Woodhouse J (2020). InterOrganizational practice committee recommendations/guidance for teleneuropsychology (TeleNP) in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 34(7/8), 1314–1344. 10.1080/13854046.2020.1767214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brearly TW, Shura RD, Martindale SL, Lazowski RA, Luxton DD, Shenal BV, & Rowland JA (2017). Neuropsychological test administration by videoconference: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychology Review, 27(2), 174–186. 10.1007/s11065-017-9349-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman JE, Ponsford J, Bagot KL, Cadilhac DA, Gardner B, & Stolwyk RJ (2020). The use of videoconferencing in clinical neuropsychology practice: A mixed methods evaluation of neuropsychologists’ experiences and views. Australian Psychologist, 55(6), 618–633. 10.1111/ap.12471 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cullum M, Bauer R, Postal K, & Taube D (2020). Risk management for teleneuropsychology [webinar]. National Register of Health Service Psychologists and The Trust Webinar Series. https://ce.nationalregister.org/videos/risk-management-for-teleneuropsychology-archived. [Google Scholar]

- Hammers DB, Stolwyk R, Harder L, & Cullum CM (2020). A survey of international clinical teleneuropsychology service provision prior to and in the context of COVID-19. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 34(7-8), 1267–1283. 10.1080/13854046.2020.1810323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt KC, & Loring DW (2020). Emory university telehealth neuropsychology development and implementation in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 34(7-8), 1352–1366. 10.1080/13854046.2020.1791960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt KC, Rodgin S, Loring DW, Pritchard AE, & Jacobson LA (2020). Transitioning to telehealth neuropsychology service: considerations across adult and pediatric care settings. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 34(7-8), 1335–1351. 10.1080/13854046.2020.1811891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Greene D (2018). Clinical neuropsychology in integrated rehabilitation care teams. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology : The Official Journal of the National Academy of Neuropsychologists, 33(3), 310–318. 10.1093/arclin/acx126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Task Force for the Development of Telepsychology Guidelines for Psychologists. (2013). Guidelines for the practice of telepsychology. American Psychologist, 68(9), 791–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcopulos BA, Guterbock TM, & Matusz EF (2020). [Formula: see text]Survey research in neuropsychology: A systematic review. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 34(1), 32–55. 10.1080/13854046.2019.1590643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra DE, Hamlet KM, Bauer RM, & Bowers D (2020a). Validity of teleneuropsychology for older adults in response to COVID-19: A systematic and critical review. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 34(7-8), 1411–1452. 10.1080/13854046.2020.1769192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra DE, Hoelzle JB, Davis JJ, & Schwartz ES (2020b). Initial changes in neuropsychologists clinical practice during the COVID-19 pandemic: A survey study. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 34(7-8), 1251–1266. 10.1080/13854046.2020.1800098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison C (2020). AACN President’s annual statement of the academy report. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 34(1), 1–12. 10.1080/13854046.2019.1694704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RK, Ludwig NN, & Jashar DT (2020). A case series illustrating the implementation of a novel tele-neuropsychology service model during COVID-19 for children with complex medical and neurodevelopmental conditions: A companion to Pritchard et al., 2020. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 1–16. 10.1080/13854046.2020.1799075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce BS, Perrin PB, & McDonald SD (2020). Demographic, organizational, and clinical practice predictors of US psychologists’ use of telepsychology. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 51(2), 184–193. 10.1037/pro0000267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard AE, Sweeney K, Salorio CF, & Jacobson LA (2020). Pediatric neuropsychological evaluation via telehealth: Novel models of care. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 34(7-8), 1367–1379. 10.1080/13854046.2020.1806359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly SE, Zane KL, McCuddy WT, Soulliard ZA, Scarisbrick DM, Miller LE, & Mahoney JJ Ill, (2020). Mental health practitioners’ immediate practical response during the COVID-19 pandemic: Observational questionnaire study. JMIR Mental Health, 7(9), e21237. 10.2196/21237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolwyk R, Hammers D, Harder L, & Cullum CM (2020). INS Webinar series. Teleneuropsychology (JeleNP) in response to COVID-19: Practical guidelines to balancing validity concerns with clinical need. International Neuropsychological Society. [Google Scholar]

- Sweet JJ, Benson LM, Nelson NW, & Moberg PJ (2015). The American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology, National Academy of Neuropsychology, and Society for Clinical Neuropsychology (APA Division 40) 2015 TCN professional practice and ‘salary survey’: Professional practices, beliefs, and incomes of U.S. Neuropsychologists. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 29(8), 1069–1162. 10.1080/13854046.2016.1140228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. (2018, May16). Geographic Areas Reference Manual: Chapter 6: Statistical Groupings of States and Counties. https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/reference/GARM/Ch6GARM.pdf

- World Health Organization. (2020). WHO Timeline - COVID-19. Retrieved April 2,72,020 from https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/27-04-2020-who-timeline—covid-19.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.