Abstract

Introduction:

Many adolescents living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) experience poverty and have access to limited resources, which can impact HIV and mental health outcomes. Few studies have analyzed the impact of economic empowerment interventions on the psychosocial wellbeing of adolescents living with HIV in low resource communities, and this study aims to examine the mediating mechanism(s) that may explain the relationship between a family economic empowerment intervention (Suubi + Adherence) and mental health outcomes for adolescents (ages 10–16 at enrollment) living with HIV in Uganda.

Method:

We utilized data from Suubi + Adherence, a large-scale six-year (2012–2018) longitudinal randomized controlled trial (N = 702). Generalized structural equation models (GSEMs) were conducted to examine 6 potential mediators (HIV viral suppression, food security, family assets, and employment, HIV stigma, HIV status disclosure comfort level, and family cohesion) to determine those that may have driven the effects of the Suubi + Adherence intervention on adolescents’ mental health.

Results:

Family assets and employment were the only statistically significant mediators during follow-up (β from −0.03 to −0.06), indicating that the intervention improved family assets and employment which, in turn, was associated with improved mental health. The proportion of the total effect mediated by family assets and employment was from 42.26% to 71.94%.

Conclusions:

Given that mental health services provision is inadequate in SSA, effective interventions incorporating components related to family assets, employment, and financial stability are crucial to supporting the mental health needs of adolescents living with HIV in under-resourced countries like Uganda. Future research should work to develop the sustainability of such interventions to improve long-term mental health outcomes among this at-risk group.

Keywords: Adolescents, Mental health, Depression, HIV, Economic intervention, Sub-saharan Africa, Uganda, Structural equation model

1. Introduction

By the year 2017, approximately 36.9 million people worldwide were living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), and approximately 1.8 million were adolescents under the age of 15 (UNAIDS, 2018). Most of these youth live in economically fragile and under-resourced parts of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) (Singer et al., 2015; Weiser et al., 2014). This points to economic deprivation and the availability of limited resources as factors that further exacerbate the poor health conditions of young people in the SSA region (Hall et al., 2019). To illustrate, families living in poverty may face challenges in accessing HIV treatment due to a lack of childcare or medical resources in their communities and high transportation costs to health centers (Ahmed et al., 2017). In many African settings and Uganda in particular, adolescents living with HIV (ALWHIV) are less likely to live with a biological parent, yet the extended families taking care of many of these young people report experiencing added financial and emotional difficulties as a result of added family responsibilities (Kagotho, 2012), a phenomenon likely to negatively affect their (ALWHIV) overall mental health and treatment outcomes (i.e., viral suppression). Thus, in general, persons living with HIV (PLWHIV), including ALWHIV, tend to have increased comorbidities, psychological distress, and mortality related to their HIV status (Frigati et al., 2020; Lwidiko et al., 2018). Adolescents who grow up in poverty usually demonstrate higher levels of hopelessness, a lower sense of self-concept, and other poor mental health outcomes, such as depression (Kemigisha et al., 2019; Kivumbi et al., 2019). ALWHIV may also face social isolation, stigmatization and be chastised due to their HIV status, which places a large burden on their mental health (McHenry et al., 2016; Mellins and Malee, 2013; Mellins et al., 2011). Mental health comorbidities may also have substantial HIV-related negative effects on adolescents, such as decreased antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence (Magidson et al., 2017; Okawa et al., 2018; Umar et al., 2019).

Depression is the most prevalent psychiatric disorder among PLWHIV in SSA (Bernard et al., 2017; Remien et al., 2019). Past research conducted among ALWHIV in SSA found that the prevalence of depressive symptoms varied between 14 and 38% among those receiving ART (Bernard et al., 2017; Kemigisha et al., 2019; Remien et al., 2019). Yet, the prevalence of depression among ALWHIV in Uganda is approximately 40% (Kinyanda et al., 2020; Nalugya-Sserunjogi et al., 2016). The high prevalence rates of depression among ALWHIV in Uganda highlights the importance of assessing depression risk factors, such as hopelessness and self-concept when evaluating the effects of an intervention on their mental health. Hopelessness is significantly and positively associated with depression (Haeffel et al., 2017); and stigma associated with HIV can reduce self-concept and cause depressive symptoms among ALWHIV (Turan et al., 2017).

Research evidence exists supporting family economic empowerment approaches as a means for reducing HIV-related risk behaviors among ALWHIV and improving their psychosocial wellbeing (Han et al., 2013; Skeen et al., 2017; Ssewamala et al., 2009; Ssewamala et al., 2012). In particular, infusion of financial resources into poor households through savings-led economic empowerment approaches, augmented with financial literacy training and mentorship, have been shown to improve psychosocial outcomes (Ssewamala et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2018). The economic empowerment approaches that emphasize asset building through savings-led approaches and financial management skills as used in the current study are guided by Nobel laureate Amartya Sen’s capability approach (Sen, 1984, 1985) and asset theory (Sherraden, 1991). These frameworks highlight the critical role of building assets, human capital (i.e., education, employment), supportive social networks, and the related asset effects that come with asset-ownership. In turn, asset-ownership offers a buffer to individuals and/or families from negative health outcomes (Van Bortel, Wickramasinghe, Morgan and Martin, 2019). Specifically, asset theorists posit that a family’s economic/financial assets can affect the psychological wellbeing of individuals (Sherraden, 1989, 1990). Studies indicate that the financial assets of a family are positively and significantly associated with the mental health functioning of adolescents affected by HIV/AIDS (Han et al., 2013; Ssewamala et al., 2012). Other specific personal factors, such as, employment, family cohesion, and food security; HIV stigma and HIV status comfort level; and HIV viral load suppression may play a critical role in the effectiveness of an economic empowerment intervention, which will consequently influence adolescent’s mental health (Hudelson and Cluver, 2015; Galárraga et al., 2013).

Prior studies have examined the impact of economic empowerment on the psychosocial wellbeing of adolescents living with HIV in low resource communities heavily impacted by HIV/AIDS (Han et al., 2013; Kivumbi et al., 2019; Ssewamala et al., 2009). Yet, few studies have examined the potential mediators which help to explain the causal pathway between economic empowerment interventions and mental health improvements among adolescents (Karimli and Ssewamala, 2015; Karimli et al., 2019). Specifically, economic empowerment reduced child poverty, which in turn led to improved mental health outcomes. In addition, participation in the economic empowerment intervention was associated with improved adolescents’ future orientation and psychosocial outcomes by reducing hopelessness, enhancing self-concept, and improving adolescents’ confidence about their educational plans. Moreover, these studies have focused on adolescents orphaned by AIDS and, to date, no known studies have systematically analyzed potential mediators to understand which observable factors have the greatest impact on the mental wellbeing of ALWHIV in SSA. This information is crucial for ascertaining the mechanisms through which economic empowerment interventions work to successfully affect care and support for ALWHIV.

Suubi + Adherence, a six-year NIH-funded longitudinal study (2012–2018) among ALWHIV (detailed below) offers us an opportunity to address the identified gaps regarding causal pathways between economic empowerment interventions and mental health in ALWHIV. To our knowledge, the Suubi + Adherence study is the first in sub-Saharan Africa to use a savings-led economic empowerment intervention aimed at financially stabilizing ALWHIV and their families with a priori expressed hypothesis highlighting the potential of positively impacting HIV treatment adherence and outcomes using economic empowerment. The results point to the potential role of economic empowerment interventions in bolstering ART-related health outcomes such as HIV viral suppression among ALWHIV in low-resource environments (Bermudez et al., 2018; Ssewamala et al., 2020). What is not clear is the extent to which the same economic empowerment intervention being implemented in low-resource environments impacts mental health functioning, and the causal pathway. This is the question this manuscript addresses by specifically examining the mediating mechanism(s) that may explain the relationship between a family economic empowerment intervention (in this case Suubi + Adherence) and mental health outcomes for ALWHIV in Uganda.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

We used data from the Suubi + Adherence study, a six-year (2012–2018) longitudinal randomized control trial (Ssewamala et al., 2019). The Suubi + Adherence study utilized a cluster-randomized experimental design across 39 health clinics in southwestern Uganda. The study recruited ALWHIV between ages 10–16 years (N = 702 at baseline). Data were collected using repeated-measures over five-time points (baseline, 12 months, 24 months, 36 months, and 48 months).

Specifically, the study comprised two arms: a control arm (n = 19 health clinics, n = 344 participants), and a treatment arm (n = 20 health clinics, n = 358 participants). Participants in the treatment arm were offered a family economic empowerment intervention, Suubi + Adherence, for 24 months. In addition to the bolstered standard of care (SOC) described below, the intervention consisted of the following three components: (1) Child Development Accounts (CDA): a matched/incentivized savings account for each participant enrolled in the treatment arm intended for long-term goals; (2) Microenterprise and financial literacy workshops offered to the participating adolescents and their caregiving families; and (3) Peer mentorship for enrolled participants, comprising 12 educational sessions covering future planning, setting short and long term goals, and avoiding risk-taking behaviors. The CDA was held in the adolescent’s name with the primary caregiver as a co-signatory. Accumulated savings in the CDAs were matched at a ratio of one-to-one during the 24-month intervention period with a match cap equivalent to US$10 a month, kept separate from the adolescent’s own CDA. The matched funds were limited to use for primary and post-secondary education, medical bills, and/or starting a family income-generating activity. Data were collected using evidence-based clinical measures and standardized, culturally adapted assessments. The control arm participants received bolstered standard of care (SOC), including medical and psychosocial care. For medical care, per the Government of Uganda’s Ministry of Health guidelines, ALWHIV are seen monthly and laboratory data (VL and CD4 counts) is collected every six months until the patient is stabilized and then annually after that. Psychosocial SOC services are primarily provided by lay counselors and include psychosocial support and ART adherence counseling. Typically, each patient is supposed to receive two-to-four sessions of adherence counseling at initiation and when problems with non-adherence are identified.

Yet, since adherence counseling may vary significantly across HIV health care centers and clinics, the standard of care was enhanced with six adherence sessions to provide standardized and sufficient adherence counseling. Participants in the control arm reviewed content related to HIV and ART as well as ART resistance and adherence. Moreover, an adapted version of the VUKA cartoon curriculum used in South Africa (Bhana et al., 2014) was incorporated into the Suubi + Maka curriculum used in Uganda (Nabunya et al., 2015; Karimli and Ssewamala, 2015) to further strengthen the Suubi + Adherence cartoon curriculum that was provided to all participants and their caregiving families. Both VUKA and Suubi + Maka curriculums are community collaborative developments of timed intervention that focuses on preventing HIV infection in adolescents through resiliency in HIV negative pre-adolescence youth (prior to first sexual debut) and their families. Both interventions intervene at multiple levels and adopt a competency-based approach. Additionally, both interventions employ adult learning ideals, including cartoon-based narratives and vignettes to deliver curriculum content. Specifically, study participants engaged in a discussion that identified and addressed barriers to medication adherence. Further training on the use of the materials was provided to the nurses and lay counselors by the research team stationed in the field, working with a local non-government organization, Reach the Youth-Uganda.

2.2. Randomization

Stratified random sampling was utilized to assign clinic/health centers to four strata based on two characteristics: 1) geographical location (rural vs urban), and 2) health clinic level (hospital vs health centers). Each of the original 40 clinics was randomly assigned to one of the two study arms. To avoid contamination, all selected ALWHIV in the same clinic/health center received the same intervention. In sum, of the 40 clinic/health centers, 20 clinics were randomly assigned to receive bolstered SOC and the other 20 received the economic empowerment intervention. Yet, one clinic was eventually disqualified due to lack of proper government registration (i.e., required to offer HIV services, including dispersing of ARTs) resulting in 19 clinics in the treatment arm. In addition, to be included in the study, adolescents had to meet the following criteria: (1) ages 10–16 years at recruitment; (2) HIV positive and aware of their status; (3) receiving antiretroviral therapy and care from one of the participating registered health clinics in Southern Uganda; and (4) be living within a family (not necessarily biological parents).

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the following ethics and institutional review boards: Makerere University School of Public Health (Protocol 210); Columbia University (Protocol AAAK3852); and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (Protocol SS 2969). All adolescent participants provided written assent for participation in the study, and their caregiving families gave written informed consent for their adolescent to participate. Research assistants (RAs) with certifications in Good Clinical Practices and Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) collected data.

2.3. Measures

Outcome.

Participants’ mental health was constructed as a latent variable using three correlated indicators: hopelessness, depression, and self-concept. All the measures of these three indicators were modified to be culturally sensitive to the population of interest and have been used in previous studies (Karimli et al., 2019; Ssewamala et al., 2012; Traube et al., 2010) and treated as indicators of a latent mental health variable (Karimli et al., 2019).

Hopelessness.

The Beck Hopelessness scale is composed of 20 items that assess an individual’s pessimism and negative expectations about the future (Beck et al., 1974; Crocker et al., 1994). Each item may be answered by the participant as true or false. Items corresponding to responses in the inverse direction were reverse coded, creating summated scores in which higher scores represented more hopelessness. Scores for this variable range from 0 to 20 (α = 0.73).

Depressive symptoms.

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) was used to assess adolescents’ depressive symptoms (ages 7–19 years). The CDI is widely used as a standardized self-report instrument for assessing child and adolescents’ depressive symptoms and has proven successful across cultural contexts (Sun and Wang, 2015; Thompson et al., 2012). The current study used the short version composed of 14 items of the CDI adapted from the original 28-item scale, which aims to measure both emotional and functional problems that correspond with depression in children and adolescents. Each CDI item has three response options that align with varying symptom levels for clinical depression (Kovacs, 2014). Items were coded and summed to create a composite score in which higher scores indicated higher levels of depressive symptoms. The scores for this variable could range from 0 to 28 (α = 0.63).

Self-concept.

This study measured adolescents’ self-concept using 17 items adapted from the original 100-item of Tennessee Self Concept Scale (TSCS) (Fitts and Warren, 1996). Response options were provided on a Likert scale, ranging from 1 = always false to 5 = always true. Responses on each item were summed to create a total score, with higher scores indicating higher levels of self-concept. Scores for this variable ranged from 17 to 85 (α = 0.75).

2.4. Mediators

We examined six potential mediators: viral load suppression, food security, family assets and employment, HIV stigma, HIV status comfort level, and family cohesion, which we hypothesized would contribute to the effect of the intervention on adolescents’ mental health.

HIV viral suppression.

HIV viral suppression was measured as the number of copies of HIV Ribonucleic acid (RNA) in a milliliter (ml) of blood. A dichotomous variable was created to represent suppression and no suppression. Viral suppression was defined as undetectable/suppression (VL < 40 copies/ml) and detectable/failed viral suppression (VL ≥ 40 copies/ml). This is because 40 copies/ml is the lowest detectable value using the Abbott Real Time system utilized in this study. This measure of HIV viral suppression has been used in previous studies with ALWHIV in Uganda (Ssewamala et al., 2020).

Food security.

Food security was assessed using three questions: (1) number of meals per day (1 or fewer = 0 vs. 2 or more = 1); (2) frequency of eating meat or fish in the prior week (1 or fewer = 0 vs. 2 or more = 1); and (3) having breakfast on the day of interview (yes = 1 vs. no = 0) (Bermudez et al., 2016). Composite scores for each aspect were created by quantifying the number of positive response items coded “1”.

Family assets and employment.

Family assets were measured using a 20-item index (0–20) assessing the availability of tangible household assets (e.g. house, livestock, garden, and transportation; Bermudez et al., 2016). A dichotomous variable was created as low possession and high possession (6 or fewer reported assets = 0 vs. 7 or more reported assets = 1). Other items for the family assets and employment variable included caregiver employment in the formal labor market (yes = 1 vs. no = 0); available cash savings (yes = 1 vs. no = 0); caregiver participating in a formal banking institution (yes = 1 vs. no = 0); and material housing value (low value including mud or hut = 0 vs. high value including brick = 1). Composite scores for each aspect were created by quantifying the number of positive response items coded “1”.

HIV stigma.

HIV-related stigma was assessed using nine questions used in previous Suubi studies (Bermudez et al., 2016; Ssewamala et al., 2019). Participants were asked to rate how they feel about their HIV diagnosis on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = strongly agree to 4 = strongly disagree. Items were reverse coded to create summated scores, with higher scores indicating greater feelings of HIV stigma. The theoretical score range for this variable was 9–36 (α = 0.78).

HIV status disclosure comfort level.

Participants were asked to rate three scenarios for how comfortable they felt talking about their HIV status to (1) close friends, (2) family members, and (3) a girlfriend/boyfriend on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = very uncomfortable to 4 = very comfortable. Items were reverse coded to create summated scores, with higher scores indicating greater discomfort in sharing/discussing their HIV status. The theoretical score range was 3–12 (α = 0.72).

Family cohesion.

Family cohesion was measured using 8 items adapted from the Family Environment Scale (Moos, 1994) and the Family Assessment Measure (Skinner et al., 2009). Participants were asked to rate how often each item’s topic occurred in their family on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = never to 5 = always. Items were reverse coded to create summated scores, with higher scores indicating lower levels of family cohesion. Sample items include “Do your family members ask each other for help before asking non-family members for help?“. The theoretical range for this variable was 8–40 (α = 0.80).

Participant demographics.

We adjusted for baseline socio-demographic covariates including age group (10–13 years old vs.14–16 years old), gender (female vs. male), and type of primary caregiver (parents vs. other relatives).

2.5. Statistical analyses

Baseline comparisons between intervention and control groups on socio-demographic and key variables were first conducted using Taylor-linearized variance estimation. We report Rao-Scott F-statistics (Rao and Scott, 1984) for categorical variables and adjusted Wald F-statistics (design-based F) for continuous variables to account for within-clinic correlation. Significance levels were set a priori at P ≤ 0.05.

We then created generalized structural equation models (GSEMs) to test the hypothesis that the effects of the Suubi + Adherence intervention on adolescents’ mental health were driven by mediating effects. In the mediation analyses, the direct effect (c’) is the effect of the intervention on the adolescents’ mental health in the absence of the mediator. The indirect effect (a × b) represents how much of the effect of the intervention on adolescents’ mental health could be explained by a mediator. Thus, the total effect (c) of the intervention on participants’ mental health is the sum of direct and indirect effects (Sobel, 1986). We then calculated the proportion of the total effect mediated. To examine the effect of the mediators at each time of follow-up and preserve temporal ordering, we fit three separate models following the approach of Karimli et al. (2019). For Model 1, the intervention predicted the mediators at 12 months, which in turn predicted the participants’ mental health at 24 months; for Model 2, the intervention predicted the mediators at 24 months, which in turn predicted the participants’ mental health at 36 months; and for Model 3, the intervention predicted the mediators at 36 months, which in turn predicted the adolescents’ mental health at 48 months. Each SEM model was adjusted for socio-demographic characteristics including age group, gender, and type of primary caregiver. We used variance-adjusted weighted least squares estimation (WLSMV) because there is a binary mediator (i.e., viral load suppression) (Muthén et al., 1997; Rhemtulla et al., 2012). The probit link function was used for the binary mediator. For the two count mediators (i.e., food security, family assets & employment), considering they both have approximately normal distributions, we treated them as continuous variables. Standard errors and test statistics were adjusted for within-clinic clustering using robust Huber-Whiter sandwich variance estimation.

Goodness-of-fit tests were conducted to evaluate the GSEMs using chi-square test of exact fit, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) (Bentler and Bonett, 1980), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) (Browne and Cudeck, 1993), and the Standardized Root Mean. Square Residual (SRMR) (Kline, 2010). Good model fit was indicated by 1) CFI≥0.95 and SRMR≤0.08 or 2) RMSEA≤0.06 and SRMR≤0.08 (Bentler and Bonett, 1980; Hu and Bentler, 1999). Unstandardized regression coefficient (B), the 95% confidence interval (CI) for B, and standardized regression coefficient (β) for each predictor and the coefficient of determination for the latent mental health outcome explained by the intervention and mediators together (R2) are presented in Table 2. The modification indices are presented in Table 3. All GSEMs were conducted using Mplus 8.3 (Muthén and Muthén, 2017) and all other analyses were conducted using Stata SE Version 15 (StataCorp, 2017).

Table 2.

Structural equitation models examining the effects of the Suubi + Adherence intervention on children and adolescent mental health.

| Model 1: 24-month follow up (n = 676) | Model 2: 36-month follow up (n = 671) | Model 3: 48-month follow up (n = 671) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 95% CI | β | B | 95% CI | β | B | 95% CI | β | ||||

| Mental health by | ||||||||||||

| Depression | 1.00 | − | − | 0.71 | 1.00 | − | − | 0.69 | 1.00 | − | − | 0.66 |

| Hopelessness | 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.98 | 0.71 | 0.96 | 0.84 | 1.08 | 0.69 | 1.15 | 0.95 | 1.34 | 0.79 |

| Self-Concept | −2.97 | −3.31 | −2.64 | −0.75 | −3.36 | −3.79 | −2.92 | −0.77 | −3.83 | −4.15 | −3.52 | −0.84 |

| Mental health on | ||||||||||||

| Family assets & employment | 0.59 | −0.75 | −0.43 | −0.26 | −0.57 | −0.70 | −0.44 | −0.28 | −0.38 | −0.52 | −0.25 | −0.20 |

| Food security | 0.11 | −0.11 | 0.33 | 0.03 | −0.45 | −0.60 | −0.30 | −0.16 | −0.43 | −0.61 | −0.25 | −0.15 |

| Antiretroviral therapy adherence | 0.09 | −0.15 | 0.33 | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.17 | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.08 | −0.10 | 0.26 | 0.03 |

| HIV status comfort level | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.12 |

| HIV stigma | −0.07 | −0.10 | −0.04 | −0.15 | −0.11 | −0.14 | −0.08 | −0.25 | −0.13 | −0.16 | −0.11 | −0.30 |

| Family cohesion | −0.10 | −0.13 | −0.08 | −0.27 | −0.11 | −0.14 | −0.09 | −0.32 | −0.12 | −0.14 | −0.10 | −0.34 |

| Agea | 0.17 | −0.16 | 0.50 | 0.03 | 0.44 | 0.09 | 0.79 | 0.09 | 0.23 | −0.14 | 0.61 | 0.05 |

| Genderb | −0.16 | −0.46 | 0.15 | −0.03 | −0.59 | −0.91 | −0.27 | −0.13 | −0.70 | −1.00 | −0.41 | −0.15 |

| Primary caregiverc | 0.50 | 0.16 | 0.85 | 0.10 | 0.20 | −0.15 | 0.56 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 0.27 | 0.72 | 0.11 |

| Mediators on intervention | ||||||||||||

| Family assets & employment | 0.45 | 0.21 | 0.68 | 0.19 | 0.46 | 0.23 | 0.69 | 0.20 | 0.38 | 0.14 | 0.61 | 0.15 |

| Food security | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 0.10 | 0.02 | −0.09 | 0.13 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.13 | 0.10 | −0.01 |

| Antiretroviral therapy adherence | −0.07 | −0.25 | 0.10 | −0.04 | 0.08 | −0.07 | 0.24 | 0.04 | 0.10 | −0.06 | 0.27 | 0.05 |

| HIV status comfort level | 0.26 | −0.09 | 0.61 | 0.05 | 0.13 | −0.25 | 0.50 | 0.02 | 0.20 | −0.23 | 0.63 | 0.04 |

| HIV sigma | 0.11 | −0.75 | 0.96 | 0.01 | 0.64 | −0.24 | 1.51 | 0.06 | 0.16 | −0.44 | 0.75 | 0.01 |

| Family cohesion | −0.41 | −1.61 | 0.79 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.92 | 0.86 | <0.001 | −0.06 | −1.03 | 0.92 | <0.001 |

| Food security with Family assets &employment | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.33 | 0.26 |

| HIV status comfort level with HIV stigma | 2.97 | 2.23 | 3.72 | 0.21 | 0.45 | −0.19 | 1.09 | 0.03 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 1.30 | 0.03 |

| Direct effect | −0.25 | −0.64 | 0.14 | −0.05 | −0.13 | −0.43 | 0.18 | −0.03 | −0.10 | −0.45 | 0.25 | −0.02 |

| Indirect effects | ||||||||||||

| Family assets & employment | −0.26 | −0.41 | −0.11 | −0.05 | −0.26 | −0.40 | −0.13 | −0.06 | −0.14 | −0.24 | −0.05 | −0.03 |

| Food security | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.05 | <0.001 | −0.01 | −0.06 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Antiretroviral therapy adherence | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.03 | <0.001 |

| HIV status comfort level | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.04 | <0.002 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| HIV stigma | −0.01 | −0.06 | 0.05 | <0.001 | −0.07 | −0.17 | 0.03 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.10 | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Family cohesion | 0.04 | −0.08 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.10 | 0.10 | <0.001 | 0.01 | −0.11 | 0.12 | <0.001 |

| Total indirect effects | −0.18 | −0.43 | 0.06 | −0.04 | −0.32 | −0.59 | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.12 | −0.38 | 0.14 | −0.03 |

| Total effect | −0.43 | −0.95 | 0.08 | −0.08 | −0.45 | −0.82 | −0.08 | −0.10 | −0.23 | −0.69 | 0.23 | −0.05 |

. Marked bold are statistically significant unstandardized coefficients

Age: 10–13 vs. 14–16 years old; reference group: 14–16 years old.

Gender: male vs. female; reference group: female.

Primary caregiver: parents vs. other relatives; reference group: parents.

Table 3.

The results of goodness-of-fit tests for GSEMs.

| Model 1: 24-month follow up (n = 676) | Model 2: 36-month follow up (n = 671) | Model 3: 48month follow up (n = 671)) |

|---|---|---|

| Chi-square = 60.05, df = 33, p = 0.003 | Chi-square = 90.03, df = 33, p < 0.001 | Chi-square = 79.50 df = 33, p < 0.001 |

| CFI = 0.94 | CFI = 0.88 | CFI = 0.89 |

| SRMR = 0.03 | SRMR = 0.04 | SRMR = 0.04 |

| RMSEA = 0.04 | RMSEA = 0.05 | RMSEA = 0.07 |

| R2 = 0.193, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001 | R2 = 0.314, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001 | R2 = 0.349, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001 |

| % total effect mediated: 42.26% | % total effect mediated: 71.94% | % total effect mediated: 54.42% |

3. Results

Baseline characteristics.

Baseline characteristics for the entire sample and by group-assigned are shown in Table 1. Of the total 702 participants, 358 were randomly assigned to the intervention condition and 344 were assigned to the control condition. At baseline, the majority (68%) of the participants were aged 10–13 years old and 56% of the sample were females. Approximately half (47%) of the participants’ reported biological parents as their primary caregivers. The mean hopelessness score among the entire sample was 5.66 (95% CI: 5.18, 6.15), the mean depression score was 5.18 (95% CI: 4.83, 5.53), and the mean self-concept score was 67.36 (95% CI: 66.51, 68.22). None of the variables were statistically significantly different between the intervention and control groups at baseline.

Table 1.

Baseline sample characteristics among the entire sample (N = 702).

| Total | Intervention (n = 358) | Control (n = 344) | Design- based F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) or Mean [95% confidence intervals] | |||||

| Demographic covariates | |||||

| Gender | 0.02 | 0.889 | |||

| Male | 396 (56.41) | 155 (43.30) | 151 (43.90) | ||

| Female | 306 (43.59) | 203 (56.70) | 193 (56.10) | ||

| Age | 0.205 | 0.653 | |||

| 10–13 | 224 (31.91) | 239 (66.76) | 239 (69.48) | ||

| 14–16 | 478 (68.09) | 119 (33.24) | 105 (30.52) | ||

| Primary caregiver | 0.981 | 0.364 | |||

| Parents | 330 (47.01) | 179 (50.00) | 151 (43.90) | ||

| Grandparents | 206 (29.34) | 104 (29.05) | 102 (29.65) | ||

| Other relatives | 166 (23.65) | 91 (26.45) | 75 (26.45) | ||

| Outcomes | |||||

| Beck Hopelessness Scale | 5.66 [5.18, 6.15] | 5.61 [4.78, 6.43] | 5.72 [5.28, 6.16] | 0.06 | 0.814 |

| Child Depression Inventory Scale | 5.18 [4.83, 5.53] | 5.19 [4.63, 5.71] | 5.17 [4.76, 5.62] | <0.01 | 0.957 |

| Tennessee Self-Concept Scale | 67.36 [66.51, 68.22] | 67.38 [66.13, 68.62] | 67.35 [66.18, 68.52] | <0.01 | 0.973 |

| Mediators | |||||

| Family assets & employment | 2.14 [1.96, 2.32] | 2.22 [1.95, 2.49] | 2.06 [1.90, 2.21] | 1.13 | 0.294 |

| Food security | 2.16 [2.09, 2.23] | 2.18 [2.07, 2.28] | 2.15 [2.07, 2.22] | 0.24 | 0.628 |

| Antiretroviral therapy adherence | 424 (60.40) | 205 (57.26) | 219 (63.66) | 2.15 | 0.150 |

| HIV status comfort level | 9.11 [8.90, 9.32] | 8.97 [8.69, 9.26] | 9.25 [9.01, 9.49] | 2.31 | 0.137 |

| HIV stigma | 26.39 [26.00, 26.78] | 26.65 [26.11, 27.20] | 26.12 [25.66, 26.59] | 2.26 | 0.141 |

| Family cohesion | 31.76 [31.24, 32.27] | 32.07 [31.37, 32.77] | 31.43 [30.78, 32.08] | 1.80 | 0.188 |

GSEM Results.

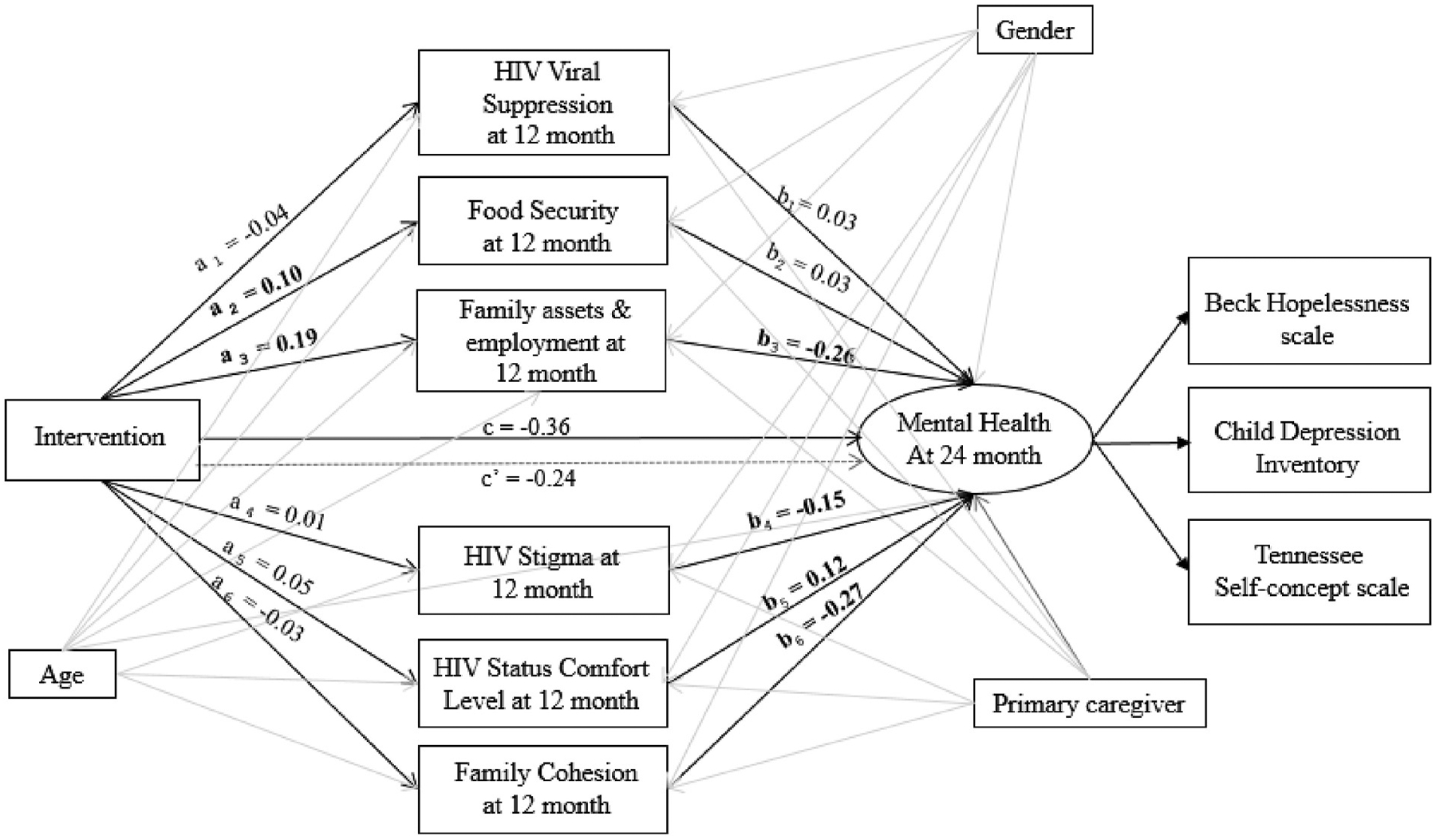

Table 2 shows the results of SEMs assessing the associations between the six intervention mediators, and participants’ mental health for at 24, 36, and, 48-month follow-up. To set the metric for the mental health latent variable, the loading of the measurement of depression was set to 1. The loadings of hopelessness (B = 0.87, 95% CI: 0.75, 0.98, β = 0.71) and self-concept (B = −2.97, 95% CI: −3.31, 2.64, β = −0.75) were both significant and substantial. At 24 months (Model 1, Fig. 1), although the total effect of the intervention on participating adolescents’ mental health was not statistically significant, it was substantial. Specially, the mental health of participants in the intervention group was 0.43 units better than the control group (B = −0.43, 95% CI: −0.95, 0.08, β = −0.08). The direct effect of the intervention on participants’ mental health was not statistically significant (B = − 0.25, 95% CI: −0.64, 0.14, β = −0.05). The indirect effect of the intervention on participants’ mental health through family assets and employment was statistically significant (B = − 0.26, 95% CI: −0.41, 0.11, β = −0.05), indicating that the intervention improved family assets and employment which, in turn, was associated with better mental health. The proportion of the total effect mediated by family assets and employment was 60.28%. None of the indirect effects of the intervention on participants’ mental health through the other five mediators were statistically significant. The total indirect effect of the intervention on participants’ mental health through the six studied mediators was not statistically significant (B = −0.18, 95% CI: −0.43, 0.06, β = −0.04) and the proportion of the total effect mediated by all the six mediators was 42.26%. The variation in the participants’ mental health explained by the intervention and the six mediators together was 19.3% (R2 = 0.193, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001) and the GSEM has a good fit to the data (χ2 (33) = 60.05, p = 0.003; CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.04, and SRMR = 0.03).

Fig. 1.

Structural equation model at 24-month follow-up.

Note:

1. Entries marked bold are statistically significant standardized coefficients.

2. a = effect of the primary predictor on the mediator; b = effect of the mediator on the outcome; c’ = the direct effect of the primary predictor on the outcome; c = the total effect of the primary predictor on the outcome.

3. The model adjusts for potential covariates: age, gender, and primary caregiver

4. This figure only presents the unstandardized coefficients for a, b, c’, and c paths. All other unstandardized coefficients and standardized coefficients produced by the model are presented in Table 2.

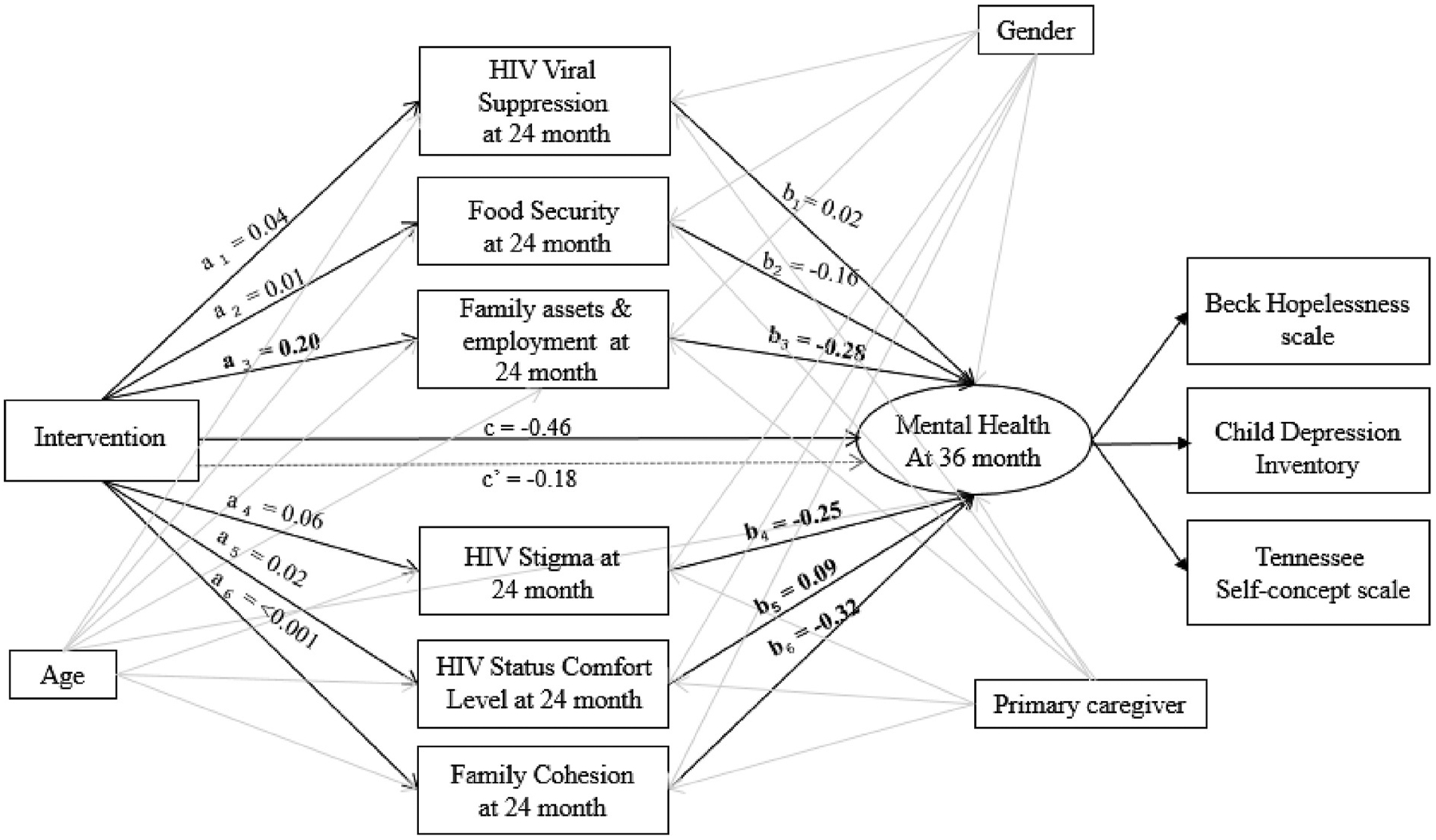

At 36 months (Model 2, Fig. 2), findings were similar to those at 24 months: there was a statistically significant total effect of the intervention on participants’ mental health. Specially, the mental health of participants in the intervention group was 0.45 units better than the control group (B = − 0.45 95% CI: −0.82, −0.08, β = −0.10). The direct effect of the intervention on participants’ mental health was not statistically significant (B = − 0.13 95% CI: −0.43, 0.18, β = −0.03). The indirect effect of the intervention on participants’ mental health through family assets and employment was statistically significant (B = −0.26, 95% CI: −0.40, −0.13, β = −0.06), indicating that the intervention improved family assets and employment which, in turn, was associated with better mental health. The proportion of the total effect mediated by family assets and employment was 58.57%. None of the indirect effects of the intervention on participants’ mental health through the other five mediators were statistically significant. The total indirect effect of the intervention on participants’ mental through the six studied mediators was statistically significant (B = −0.32, 95% CI: −0.59, −0.06, β = 0.07) and the proportion of the total effect mediated by all the 6 mediators was 71.94%. The variation in the participants’ mental health explained by the intervention and the 6 mediators together was 31.4% (R2 = 0.314, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001) and the GSEM had a good fit to the data (χ2 (33) = 90.03, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.88, RMSEA = 0.05, and SRMR = 0.04).

Fig. 2.

Structural equation model at 36-month follow-up.

Note:

1. Entries marked bold are statistically significant standardized coefficients.

2. a = effect of the primary predictor on the mediator; b = effect of the mediator on the outcome; c’ = the direct effect of the primary predictor on the outcome; c = the total effect of the primary predictor on the outcome.

3. The model adjusts for potential covariates: age, gender, and primary caregiver

4. This figure only presents the unstandardized coefficients for a, b, c’, and c paths. All other unstandardized coefficients and standardized coefficients produced by the model are presented in Table 2.

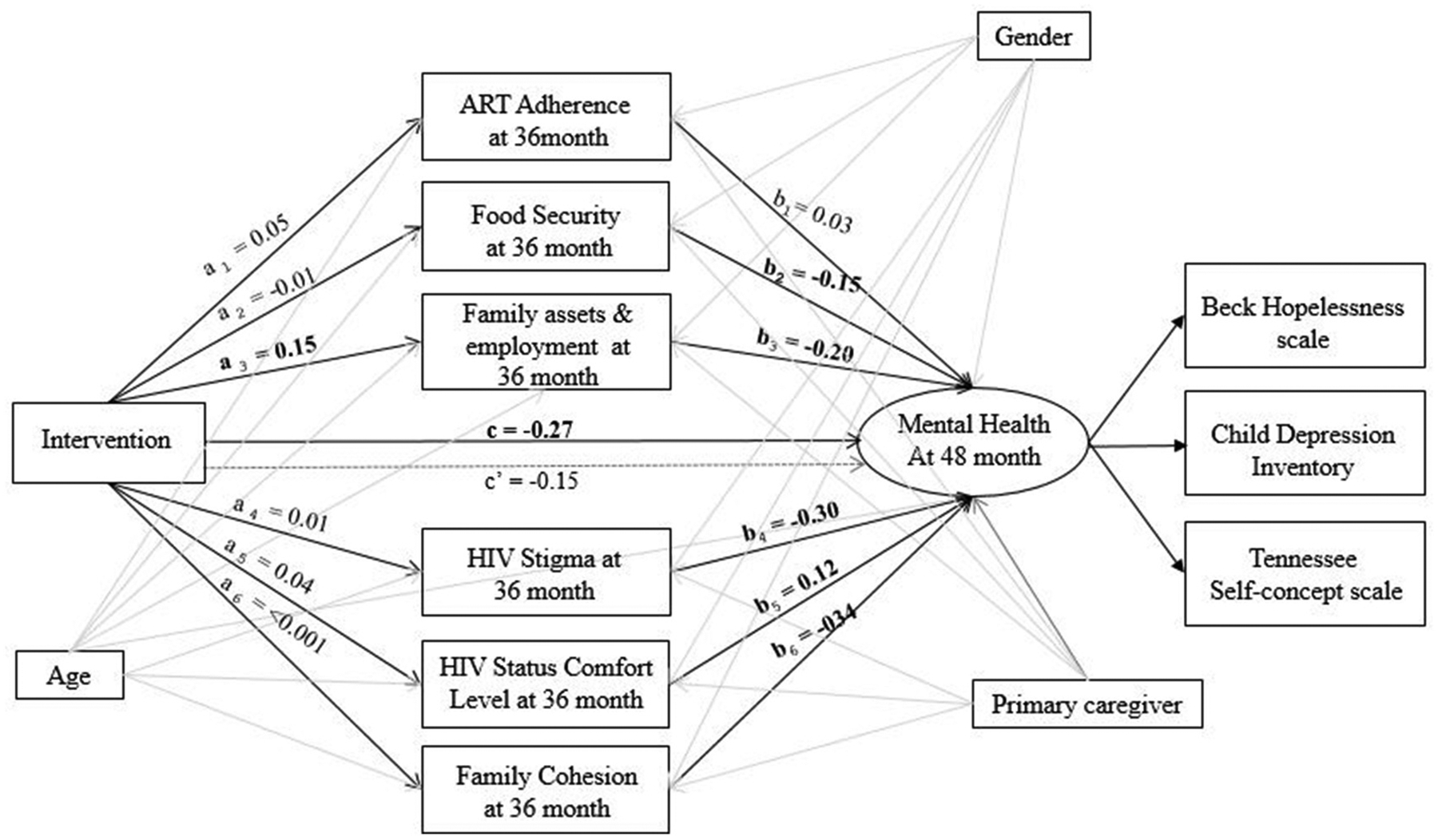

At 48 months (Model 3, Fig. 3), although the total effect of the intervention on participants’ mental health was not statistically significant, the mental health of participants in the intervention group was 0.23 units better than the control group (B = − 0.23 95% CI: −0.69, 0.23, β = −0.05). The direct effect of the intervention on participants’ mental health was not statistically significant (B = − 0.10, 95% CI: −0.45, 0.25, β = −0.02). The indirect effect of the intervention on participants’ mental health through family assets and employment was statistically significant (B = −0.14, 95% CI: −0.24, −0.05, β = −0.03), indicating that the intervention improved family assets and employment which, in turn, was associated with better mental health. The proportion of the total effect mediated by family assets and employment was 63.27%. None of the indirect effects of the intervention on participants’ mental health through the other five mediators was statistically significant. The total indirect effect of the intervention on participants’ mental through the six studied mediators was not statistically significant (B = −0.12, 95% CI: −0.38, 0.14, β = −0.03) and the proportion of the total effect mediated by all the six mediators was also 54.42% (ab/c × 100%). The variation in the participants’ mental health by the intervention and the six mediators together was 34.9% (R2 = 0.349, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001) and the SEM had a good fit to the data (χ2 (33) = 79.50, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.89, RMSEA = 0.07, and SRMR = 0.04).

Fig. 3.

Structural equation model at 48-month follow-up.

Note:

1. Entries marked bold are statistically significant standardized coefficients.

2. a = effect of the primary predictor on the mediator; b = effect of the mediator on the outcome; c’ = the direct effect of the primary predictor on the outcome; c = the total effect of the primary predictor on the outcome.

3. The model adjusts for potential covariates: age, gender, and primary caregiver

4. This figure only presents the unstandardized coefficients for a, b, c’, and c paths. All other unstandardized coefficients and standardized coefficients produced by the model are presented in Table 2.

4. Discussion

This study explored the mediating mechanisms of the impact of an economic empowerment intervention on the mental health of ALWHIV in Uganda. Results indicate that the intervention had a positive effect on participants’ mental health at each point of follow-up (24, 36, and 48 months), and the effect was significant at 24 months. This finding supports the capability framework (Sen, 1984, 1985) and asset theory (Sherraden, 1989, 1990), both of which point to positive effects of economic/financial assets on psychosocial wellbeing for young people. It is plausible that by providing adolescents and their caregiving families with financial opportunities, they were able to access food necessary for taking their medication and afford transportation to scheduled clinic days and medication refills-all of which are critical to medication adherence. Hence, reducing financial-related stress among ALWHIV and their caregiving families may consequently improve adolescents’ mental health outcomes. Although previous studies have shown that depression is a cause of lower adherence and in turn lower viral suppression (Gonzalez et al., 2011; Byakika-Tusiime et al., 2009), improvements in viral load suppression and other potential HIV-related mediators as a causal pathway for mental health improvements among ALWHIV were not fully supported in our analyses. This may be due to short-term stressors surrounding HIV symptoms and disease management which could have a more immediate impact on mental health, while improvements in overall viral load suppression, stigma, and discomfort with HIV status may have more long-term effects on mental health not captured in this study time frame. These mechanisms may not be sufficient to improve mental health symptoms but may rather be effective components of change in a larger intervention, as our results did support that HIV status comfort level, HIV stigma, and family cohesion were significant factors for the mental health of this population. Our findings point to the potential benefits of using non-traditional approaches to improve mental health outcomes among participants living with HIV. Economic interventions, including micro-savings, meant to alleviate poverty among families caring for ALWHIV, may also serve as a valid strategy to improve psychological wellbeing for adolescents (Ssewamala et al., 2012, 2020). Similar studies have found family economic empowerment interventions to significantly improve the psychosocial wellbeing of adolescents, by specifically decreasing symptoms of depression and hopelessness (Han et al., 2013; Ssewamala et al., 2012). Additionally, our findings are consistent with previous studies, which demonstrate that the positive effect(s) of an economic empowerment intervention on mental health diminish after the intervention is no longer provided (Moore et al., 2016; Prince, 2014). Future research should aim at developing sustainable economic interventions to improve long-term mental health outcomes for ALWHIV.

Results regarding which potential mediators best explain the causal pathway between the economic intervention and the mental health of adolescents demonstrated that family assets and microenterprise development were the strongest contributors to adolescent mental wellbeing. The indirect effect of this economic empowerment intervention on adolescents’ mental health demonstrated that the intervention improved family assets, including microenterprise development, which in turn was associated with better mental health functioning. This finding was consistent throughout each point of follow-up (24, 36, and 48 months). Our findings suggest that targeting family financial stability potentially reduces financial stress, and ultimately improves adolescent mental health. Thus, our results align with other findings which state that interventions without the necessary financial support components, which can help to address food insecurity or transportation barriers, may fail to adequately improve ART adherence and the mental health of young people impacted by HIV (Han et al., 2013; Ssewamala et al., 2012). Indeed, food insecurity has been found to be linked to both risk for HIV transmission/acquisition as well as lower access and adherence to ART (Tsai et al., 2011; Weiser et al., 2011; Weiser et al., 2014), and is itself a risk factor for poorer mental health outcomes (Sweetland et al., 2019; Tsai et al., 2012).

Additionally, we found that primary caregiver (parent versus other family or others) was a significant covariate in Models 1 and 3, supporting prior research findings that biological relatedness impacts child support and development. For example, orphaned children who lost both parents and those cared for by other relatives are less likely than those with a surviving biological parent and those cared for by a grandparent to have the same opportunities of being introduced to other supportive individuals outside of their households. This is consistent with other studies which indicate the differential treatment of orphans based on biological relatedness, where caregivers are inclined to give more love, attention, and support to children they parent or grandparent (Nabunya et al., 2019; Parker and Short, 2009; Roby et al., 2016). It is important for further research to consider these nuances in family structure and factors surrounding child development and for future intervention studies to integrate financial support components into their designs if the aim is to improve the mental well-being of ALWHIV in low resource areas.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this research is that it is a randomized control trial (RCT) with a longitudinal study design, which allowed us to thoroughly analyze the effect(s) of an economic empowerment intervention on the mental health of ALWHIV both during and after the implementation, and to arguably make stronger inferences than those available with cross-sectional data. Longitudinal datasets allow for changes in psychosocial outcomes to be evaluated over time and the use of a control group allows these changes to be compared to a sample not exposed to the intervention. Yet, several limitations are relevant to consider when interpreting our findings. The self-report measures used in this study make it susceptible to social desirability bias, which can affect the results. Further research is also needed to compare the psychological improvements made by those receiving an economic empowerment intervention with those receiving more traditional psychological assistance (i.e., cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, etc.) or those receiving both intervention components. The measures used to assess mental health in this study may not have been full range/exhaustive, which may limit the internal validity of our results. For example, although all measurements used in this study were proved valid and reliable by previous research, the Cronbach’s αs of the CDI used to measure depressive symptoms is questionable by its criteria (i.e., Cronbach’s αs<0.7), suggesting this measurement may lack internal consistency and may not be appropriate for our sample. Yet, because we did not use other measures to assess depression and this is one of the primary outcomes of the study, we believe it is still meaningful to present these results. We recommend all the results related to depression be taken into consideration in the context of this limitation. The adolescents in this study aged throughout the multiple wave follow-up of this intervention and the measures being used may operate differently throughout adolescence. Additionally, there may be unknown external factors, life events, and environmental changes that can explain within and between-subject variations in our results. Future research including more indicators needs to be done to understand the mechanisms by which economic empowerment interventions lead to better mental health outcomes.

5. Conclusions

Despite the limitations highlighted above, this study expands the literature on the effectiveness of economic empowerment interventions in addressing mental health outcomes among ALWHIV, providing additional insight into the mediators that most greatly contribute to positive mental health outcomes. Within low resource settings, SSA adolescents struggle with not only accessing necessities but also with mental health and well-being. Given that mental health services are severely lacking in SSA (Charlson et al., 2014; Sankoh et al., 2018) and are inaccessible by many youth in Uganda, new solutions like Suubi + Adherence and VUKA that show promise must be tested and scaled up to improve access to mental health care. Finally, our findings indicate that economic empowerment interventions improve viral suppression, adherence to medication, mental health, and economic security and reduce transport barriers to HIV clinics (Kivumbi et al., 2019; Ssewamala et al., 2020). Therefore, for sustainability, there is potential to incorporate these interventions into the HIV care continuum through the ministry of health and the local district health departments.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for the Suubi + Adherence Study was provided by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD), Grant #R01HD074949 (PI: Fred M Ssewamala) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Grant #K02DA043657 (PI: Patricia Cavazos-Rehg). The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health. We are grateful to the staff and the volunteer team at the International Center for Child Health and Development in Masaka, Uganda (led by Flavia Namuwonge and Christopher Damulira) for monitoring the study implementation process. Our special thanks go to the 39 health clinics, and to the children and their caregiving families who agreed to participate in the study.

References

- Ahmed CV, Jolly P, Padilla L, Malinga M, Harris C, Mthethwa N, Preko P, 2017. A qualitative analysis of the barriers to antiretroviral therapy initiation among children 2 to 18 months of age in Swaziland . Afr. J. AIDS Res 16 (4), 321–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L, 1974. The measurement of pessimism: the hopelessness scale. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 42 (6), 861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Bonett DG, 1980. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull 88 (3), 588. [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez LG, Jennings L, Ssewamala FM, Nabunya P, Mellins C, McKay M, 2016. Equity in adherence to antiretroviral therapy among economically vulnerable adolescents living with HIV in Uganda. AIDS Care 28 (Suppl. 2), 83–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez LG, Ssewamala FM, Neilands TB, Lu L, Jennings L, Nakigozi G, Mukasa M, 2018. Does economic strengthening improve viral suppression among adolescents living with HIV? Results from a cluster randomized trial in Uganda. AIDS Behav 22 (11), 3763–3772. 10.1007/s10461-018-2173-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard C, Dabis F, de Rekeneire N, 2017. Prevalence and factors associated with depression in people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One 12 (8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhana A, Mellins CA, Petersen I, Alicea S, Myeza N, Holst H, Nestadt DF, 2014. The VUKA family program: piloting a family-based psychosocial intervention to promote health and mental health among HIV infected early adolescents in South Africa. AIDS Care 26 (1), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R, 1993. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen, K.A., Long, J.S. (Eds.), Testing Structural Equation Models. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA, pp. 111–135. [Google Scholar]

- Byakika-Tusiime J, Crane J, Oyugi JH, Ragland K, Kawuma A, Musoke P, Bangsberg DR, 2009. Longitudinal antiretroviral adherence in HIV+ Ugandan parents and their children initiating HAART in the MTCT-Plus family treatment model: role of depression in declining adherence over time. AIDS Behav. 13 (1), 82–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson FJ, Diminic S, Lund C, Degenhardt L, Whiteford HA, 2014. Mental and substance use disorders in sub-Saharan Africa: predictions of epidemiological changes and mental health workforce requirements for the next 40 years. PloS One 9 (10), e110208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Luhtanen R, Blaine B, Broadnax S, 1994. Collective self-esteem and psychological well-being among White, Black, and Asian college students. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull 20 (5), 503–513. [Google Scholar]

- Fitts WH, Warren WL, 1996. Tennessee Self-Concept Scale: TSCS-2. Western Psychological Services Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Frigati LJ, Ameyan W, Cotton MF, Gregson CL, Hoare J, Jao J, Rukuni R, 2020. Chronic Comorbidities in Children and Adolescents with Perinatally Acquired HIV Infection in Sub-saharan Africa in the Era of Antiretroviral Therapy. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galárraga O, Genberg BL, Martin RA, Laws MB, Wilson IB, 2013. Conditional economic incentives to improve HIV treatment adherence: literature review and theoretical considerations. AIDS Behav. 17 (7), 2283–2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, Safren SA, 2011. Depression and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: a review and meta-analysis. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr 58 (2), 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeffel GJ, Hershenberg R, Goodson JT, Hein S, Square A, Grigorenko EL, Chapman J, 2017. The hopelessness theory of depression: clinical utility and generalizability. Cognit. Ther. Res 41 (4), 543–555. [Google Scholar]

- Hall BJ, Garabiles MR, de Hoop J, Pereira A, Prencipe L, Palermo TM, 2019. Perspectives of adolescent and young adults on poverty-related stressors: a qualitative study in Ghana, Malawi and Tanzania. BMJ Open 9 (10), e027047. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C, Ssewamala F, Wang J, 2013. Family economic empowerment and mental health among AIDS-affected children living in AIDS-impacted communities: evidence from a randomised evaluation in southwestern Uganda. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 67 (3), 225–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L. t., Bentler PM, 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model 6 (1), 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hudelson C, Cluver L, 2015. Factors associated with adherence to antiretroviral therapy among adolescents living with HIV/AIDS in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. AIDS Care 27 (7), 805–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagotho N, 2012. A future of possibilities: educating children living in HIV impacted households. Int. J. Educ. Dev 32 (3), 394–400. [Google Scholar]

- Karimli L, Ssewamala FM, 2015. Do savings mediate changes in adolescents’ future orientation and health-related outcomes? Findings from randomized experiment in Uganda. J. Adolesc. Health 57 (4), 425–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimli L, Ssewamala FM, Neilands TB, Wells CR, Bermudez LG, 2019. Poverty, economic strengthening, and mental health among AIDS orphaned children in Uganda: mediation model in a randomized clinical trial. Soc. Sci. Med 228, 17–24. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemigisha E, Zanoni B, Bruce K, Menjivar R, Kadengye D, Atwine D, Rukundo GZ, 2019. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and associated factors among adolescents living with HIV/AIDS in South Western Uganda. AIDS Care 31 (10), 1297–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinyanda E, Salisbury TT, Muyingo SK, Ssembajjwe W, Levin J, Nakasujja N, Araya R, 2020. Major depressive disorder among HIV infected youth in Uganda: incidence, persistence and their predictors. AIDS Behav. 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivumbi A, Byansi W, Ssewamala FM, Proscovia N, Damulira C, Namatovu P, 2019. Utilizing a family-based economic strengthening intervention to improve mental health wellbeing among female adolescent orphans in Uganda. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Ment. Health 13 (1), 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, 2014. Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI and CDI 2) the Encyclopedia Of Clinical Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Lwidiko A, Kibusi SM, Nyundo A, Mpondo BC, 2018. Association between HIV status and depressive symptoms among children and adolescents in the Southern Highlands Zone, Tanzania: a case-control study. PloS One 13 (2), e0193145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magidson JF, Saal W, Nel A, Remmert JE, Kagee A, 2017. Relationship between depressive symptoms, alcohol use, and antiretroviral therapy adherence among HIV-infected, clinic-attending patients in South Africa. J. Health Psychol 22 (11), 1426–1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHenry MS, Nyandiko WM, Scanlon ML, Fischer LJ, McAteer CI, Aluoch J, Vreeman RC, 2016. HIV stigma: perspectives from Kenyan child caregivers and adolescents living with HIV. J. Int. Assoc. Phys. AIDS Care 16 (3), 215–225. 10.1177/2325957416668995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellins CA, Malee KM, 2013. Understanding the mental health of youth living with perinatal HIV infection: lessons learned and current challenges. J. Int. AIDS Soc 16 (1), 18593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellins CA, Tassiopoulos K, Malee K, Moscicki AB, Patton D, Smith R, Usitalo A, Allison SM, Van Dyke R, Seage GR III, 2011. Behavioral health risks in perinatally HIV-exposed youth: co-occurrence of sexual and drug use behavior, mental health problems, and nonadherence to antiretroviral treatment. AIDS Patient Care STDS 25 (7), 413–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore THM, Kapur N, Hawton K, Richards A, Metcalfe C, Gunnell D, 2016. Interventions to reduce the impact of unemployment and economic hardship on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. Psychol. Med 47 (6), 1062–1084. 10.1017/S0033291716002944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, 1994. Family Environment Scale Manual. Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Du S, Spisic D, Muthén B, du Toit S, 1997. Robust Inference Using Weighted Least Squares and Quadratic Estimating Equations in Latent Variable Modeling with Categorical and Continuous Outcomes.

- Muthén L, Muthén B, 2017. Mplus (Version 8)[computer software].(1998–2017). Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Nabunya P, Padgett D, Ssewamala FM, Courtney ME, Neilands T, 2019. Examining the nonkin support networks of orphaned adolescents participating in a family-based economic-strengthening intervention in Uganda. J. Community Psychol 47 (3), 579–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabunya P, Ssewamala FM, Mukasa MN, Byansi W, Nattabi J, 2015. Peer mentorship program on HIV/AIDS knowledge, beliefs, and prevention attitudes among orphaned adolescents: an evidence based practice. Vulnerable Child. Youth Stud 10 (4), 345–356. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalugya-Sserunjogi J, Rukundo GZ, Ovuga E, Kiwuwa SM, Musisi S, Nakimuli-Mpungu E, 2016. Prevalence and factors associated with depression symptoms among school-going adolescents in Central Uganda. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Ment. Health 10 (1), 39. 10.1186/s13034-016-0133-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okawa S, Mwanza Kabaghe S, Mwiya M, Kikuchi K, Jimba M, Kankasa C, Ishikawa N, 2018. Psychological well-being and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among adolescents living with HIV in Zambia. AIDS Care 30 (5), 634–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker EM, Short SE, 2009. Grandmother coresidence, maternal orphans, and school enrollment in sub-Saharan Africa. J. Fam. Issues 30 (6), 813–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince J, 2014. The Impact of Access to Microfinance on Mental Health.

- Rao JN, Scott AJ, 1984. On chi-squared tests for multiway contingency tables with cell proportions estimated from survey data. Ann. Stat 46–60. [Google Scholar]

- Remien RH, Stirratt MJ, Nguyen N, Robbins RN, Pala AN, Mellins CA, 2019. Mental health and HIV/AIDS: the need for an integrated response. AIDS (London, England) 33 (9), 1411–1420. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhemtulla M, Brosseau-Liard PÉ, Savalei V, 2012. When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychol. Methods 17 (3), 354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roby JL, Erickson L, Nagaishi C, 2016. Education for children in sub-Saharan Africa: predictors impacting school attendance. Child. Youth Serv. Rev 64, 110–116. [Google Scholar]

- Sankoh O, Sevalie S, Weston M, 2018. Mental health in Africa. The Lancet Global Health 6 (9), e954–e955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen A, 1984. The living standard. Oxf. Econ. Pap 36, 74–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sen A, 1985. Well-being, agency and freedom: the Dewey lectures 1984. J. Philos 82 (4), 169–221. [Google Scholar]

- Sherraden M, 1989. Individual development accounts. The Entrepreneurial Economy Review 8 (5), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sherraden M, 1990. Stakeholding: notes on a theory of welfare based on assets. Soc. Serv. Rev 64 (4), 580–601. [Google Scholar]

- Sherraden MW, 1991. Assets and the Poor. ME Sharpe. [Google Scholar]

- Singer AW, Weiser SD, McCoy SI, 2015. Does food insecurity undermine adherence to antiretroviral therapy? A systematic review. AIDS Behav. 19, 1510–1526. 10.1007/s10461-014-0873-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeen SA, Sherr L, Croome N, Gandhi N, Roberts KJ, Macedo A, Tomlinson M, 2017. Interventions to improve psychosocial well-being for children affected by HIV and AIDS: a systematic review. Vulnerable Child. Youth Stud 12 (2), 91–116. 10.1080/17450128.2016.1276656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA, Steinhauer PD, Santa-Barbara J, 2009. The family assessment measure. Can. J. Community Ment. Health 2 (2), 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME, 1986. Some new results on indirect effects and their standard errors in covariance structure models. Socio. Methodol 16, 159–186. 10.2307/270922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ssewamala, Dvalishvili D, Mellins CA, Geng EH, Makumbi F, Neilands TB, Bahar Sensoy, 2020. The long-term effects of a family based economic empowerment intervention (Suubi+ Adherence) on suppression of HIV viral loads among adolescents living with HIV in southern Uganda: findings from 5-year cluster randomized trial. PloS One 15 (2), e0228370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ssewamala F, Neilands T, Waldfogel J, Ismayilova L, 2012. The impact of a comprehensive microfinance intervention on depression levels of AIDS-orphaned children in Uganda. J. Adolesc. Health 50 (4), 346–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ssewamala FM, Byansi W, Bahar OS, Nabunya P, Neilands TB, Mellins C, Nakigozi G, 2019. Suubi+Adherence study protocol: a family economic empowerment intervention addressing HIV treatment adherence for perinatally infected adolescents. Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications 16, 100463. 10.1016/j.conctc.2019.100463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ssewamala FM, Han C-K, Neilands TB, 2009. Asset ownership and health and mental health functioning among AIDS-orphaned adolescents: findings from a randomized clinical trial in rural Uganda. Soc. Sci. Med 69 (2), 191–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp, 2017. Stata/SE (Version 15.0).

- Sun S, Wang S, 2015. The children’s depression inventory in worldwide child development research: a reliability generalization study. J. Child Fam. Stud 24 (8), 2352–2363. 10.1007/s10826-014-0038-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sweetland AC, Norcini Pala A, Mootz J, Kao JCW, Carlson C, Oquendo MA, Wainberg M, 2019. Food insecurity, mental distress and suicidal ideation in rural Africa: evidence from Nigeria, Uganda and Ghana. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatr 65 (1), 20–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RD, Craig AE, Mrakotsky C, Bousvaros A, DeMaso DR, Szigethy E, 2012. Using the Children’s Depression Inventory in youth with inflammatory bowel disease: support for a physical illness-related factor. Compr. Psychiatr 53 (8), 1194–1199. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traube D, Dukay V, Kaaya S, Reyes H, Mellins C, 2010. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Child Depression Inventory for use in Tanzania with children affected by HIV. Vulnerable Child. Youth Stud 5 (2), 174–187. 10.1080/17450121003668343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai AC, Bangsberg DR, Emenyonu N, Senkungu JK, Martin JN, Weiser SD, 2011. The social context of food insecurity among persons living with HIV/AIDS in rural Uganda, 1982 Soc. Sci. Med 73 (12), 1717–1724. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai AC, Bangsberg DR, Frongillo EA, Hunt PW, Muzoora C, Martin JN, Weiser SD, 2012. Food insecurity, depression and the modifying role of social support among people living with HIV/AIDS in rural Uganda. Soc. Sci. Med 74 (12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umar E, Levy JA, Donenberg G, Mackesy-Amiti ME, Pujasari H, Bailey RC, 2019. The influence of self-efficacy on the relationship between depression and hiv-related stigma with ART adherence among the youth in Malawi. Jurnal Keperawatan Indonesia 22 (2), 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS, 2018. UNAIDS Data 2018. Retrieved from.http://aidsinfo.unaids.org/.

- Van Bortel T, Wickramasinghe ND, Morgan A, Martin S, 2019. Health assets in a global context: a systematic review of the literature. BMJ open 9 (2), e023810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JSH, Ssewamala FM, Neilands TB, Bermudez LG, Garfinkel I, Waldfogel J, You J, 2018. Effects of financial incentives on saving outcomes and material well-being: evidence from a randomized controlled trial in Uganda. J. Pol. Anal. Manag 37 (3), 602–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser SD, Palar K, Frongillo EA, Tsai AC, Kumbakumba E, Depee S, Hunt PW, Ragland K, Martin J, Bangsberg DR, 2014. Longitudinal assessment of associations between food insecurity, antiretroviral adherence and HIV treatment outcomes in rural Uganda. Jan 2 AIDS 28 (1), 115–120. 10.1097/01.aids.0000433238.93986.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser SD, Young SL, Cohen CR, Kushel MB, Tsai AC, Tien PC, Hatcher AM, Frongillo EA, Bangsberg DR, 2011. Conceptual framework for understanding the bidirectional links between food insecurity and HIV/AIDS. Am J Clin Nutr. December94 (6), 1729S–1739S. 10.3945/ajcn.111.012070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]