Abstract

Background

Patients with functional somatic syndromes (FSS) might be prone to potentially harmful medical investigations in ambulatory care. The primary aim was to investigate whether patients with FSS are more likely to undergo diagnostic examinations such as radiography, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and outpatient surgical procedures. The secondary aim was to evaluate the extent to which coordination of care by primary care physicians reduces healthcare utilization.

Methods

Retrospective cohort study using longitudinal regression analysis of routine data. FSS patients were weighted in the regression model to allow a representative comparison with the Bavarian population. The observation period was from 5 years before until 10 years after the diagnosis of FSS.

Results

The cohort comprised 43 676 patients with FSS and a control group of 50 003 patients without a diagnosis of FSS. The FSS patients exhibited continuously increased healthcare utilization over the 15-year period. The relative risk (RR) for FSS patients was up to 1.48 (95% confidence interval [1.46; 1.50]) for radiography, 2.01 [1.94; 2.08] for CT, 1.91 [1.87; 1.96] for MRI, and 1.30 [1.27; 1.34] for outpatient surgery. Compared with patients whose treatment was coordinated by their primary care physician, patients with no such coordination showed higher service utilization. The ambulatory care costs were up to 1.37 [1.36; 1.38] times greater.

Conclusions

Patients with FSS more frequently undergo potentially harmful and costly diagnostic testing and outpatient surgery. Coordination of care by the primary care physician is associated with lower healthcare utilization.

The prevalence of functional somatic syndromes (FSS) in primary care is estimated at 26 to 35%, as shown by a systematic review including 32 studies from 24 countries (1). Moreover, patients with FSS often have psychic comorbidity in the form of increased depression or anxiety (2). In many cases the high levels of mental and physical distress lead patients to consult numerous different physicians (3). This leads ultimately to major challenges for medical practitioners of all specialties, because as a general rule further diagnostic investigation is demanded for allegedly definitive exclusion of organic diseases (4). Accordingly, the impact on high healthcare utilization is well documented (5– 7). Studies from (tertiary) inpatient settings have, in isolated cases, shown that as a consequence of such help-seeking behavior, patients with FSS undergo more frequent diagnostic examinations and perhaps also more surgical procedures, which are not only expensive but also potentially harmful (8– 12). However, the impact of somatization disorders on healthcare utilization with respect to potentially harmful investigations in ambulatory care is still unclear.

In the everyday treatment setting it is extremely difficult to satisfy the patients with regard to their medical care (13, 14). The recommended treatment strategy is reattribution, consisting of a structured consultation in which a psychosomatic explanation for the functional physical symptoms is worked out in cooperation with the patient (15– 19). The aim of this reframing is for the patient to learn to see their physical complaints in the context of their own reinforcing and mitigating psychosocial stress factors. In the context of the biopsychosocial model, a good doctor–patient relationship helps to establish trust and thus facilitates the reattribution of physical symptoms to stress situations, perhaps with establishment of an association with familial and occupational circumstances.

The definition of general practice focuses on long-term, patient-centered care by the primary care physician, with inclusion of psychosocial issues and mental health in a trust-based relationship; other essential aspects are continuity and coordination of care (18, 19). The coordination of specialist care may be of particular importance for patients with FSS to reduce the utilization of repeated and potentially harmful medical investigations, as it can be assumed that free access to specialists tends to lead to performance of inappropriate procedures. Patients who might benefit from coordinated care may be identifiable by virtue of increased healthcare utilization in terms of physician contacts, referrals, and frequent certificates of work incapacity (6, 20).

The primary aim of the routine data analysis was to evaluate the extent to which FSS patients exhibit an increased frequency of costly and potentially harmful diagnostic and medical procedures over an extended period. Furthermore, we sought to establish the impact of coordination of care by primary care physicians.

Materials and methods

Study design

We conducted a longitudinal analysis of routine data. The cohort consisted of FSS patients and control patients with no record of FSS. The patients were observed over a 15-year period between 2005 and 2019, from 5 years before diagnosis to 10 years thereafter (eMethods).

Study data

The anonymized dataset was provided by the Bavarian Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians. All diagnoses relevant to the treatment episodes were recorded on a quarterly basis using ICD-10 codes. Outpatient surgery was documented using the German Classification of Operations and Procedures (OPS).

Cohort

The cohort consisted of patients aged between 18 and 50 years with a first diagnosis of one of the following functional somatic syndromes in the year 2010: chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS: ICD-10-GM codes F48.0 and G93.3), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS: F45.32 and K58), other functional intestinal disorders (FID: K59), fibromyalgia (FM: M79.7), tension headache (TH: G44.2), and somatoform disorder (SD: F45.0). Children, adolescents, and patients older than 50 years were excluded to avoid misclassification of symptoms or confusion of functional physical complaints with somatic diseases. Patients were excluded if observed for less than 2 years before or after first diagnosis, thus ensuring an adequate period of observation.

A control group was drawn from the pool of patients with no recorded FSS diagnosis who met the same inclusion criteria. The sample was stratified by age, gender, and place of residence, with the number of participants in each group chosen to be representative of the Bavarian population.

Measures of interest

As a general measure of healthcare utilization, we selected the following diagnostic procedures during a 15-year period: radiography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), excluding screening mammography. Outpatient surgical procedures were used to represent potentially harmful medical procedures in general. The overall costs of ambulatory care were analyzed in Euros per quarterly billing period after any budgetary and accounting processes.

Definition of coordinated care

The patients were divided into three groups, reflecting the coordination of their ambulatory care during the quarter. The first group comprised patients who consulted exclusively primary care physicians, including general internists (PCP only). The second group, coordinated patients (CP), consulted one or more office-based specialists only on referral by a PCP. The third group, the “non-coordinated patients” (NP), consulted one or more specialist without referral by a PCP. To ascertain the effect of PCP-based care, we combined the PCP-only and CP groups into a “PCP-based care” (PBC group). This PBC group was compared with the NP group. In a sensitivity analysis we compared the CP and NP groups, on the assumption that patients with specialist contact had more severe forms of FSS.

Statistical analysis

We calculated time-dependent relative risks (risk ratios [RR]) to quantify the differences in healthcare utilization between the FSS group and the control groups and between coordinated and non-coordinated FSS patients.

The outcomes of interest were modeled using longitudinal regression models, with the unit of time defined by the quarterly billing period. A generalized estimating equation (GEE) approach was applied to account for intrapatient autocorrelation, assuming a first-order autoregressive variance structure. The models incorporated the age and sex of the patient as well as the type of residential district, categorized by means of a four-level classification ranging from “large city” to “sparsely populated rural area” provided by the Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs, and Spatial Development (21).

Charlson comorbidities were calculated for the year prior to first diagnosis and included in the regression model (22). A previous psychological disorder, defined as a confirmed diagnosis of depression (ICD-10 code F32 or F33), anxiety (F41), or stress disorder (F43), was included as a further relevant comorbidity. In order to ensure comparability of the groups, all FSS patients were weighted in the regression model such that the distribution of age, sex, and district of residence matched that of the Bavarian population aged between 18 and 50 in the year 2010. The analyses were conducted by the statistician ED. Details of the statistical analysis are presented in the eMethods.

Results

Of the 108 412 patients with a first diagnosis of a FSS in the year 2010, 48 225 were aged between 18 and 50 years. Of these, 43 676 patients had been observed for at least 2 years before and after diagnosis and could thus be included for analysis (efigure). The FSS patients were compared with 50 003 patients from the control group. The total cohort therefore comprised 93 679 patients, of whom 93% were observed for at least 4 years before diagnosis and over 90% for at least 9 years after diagnosis. FSS patients were more often female, were more likely to have had previous psychological disorders, and more often exhibited coordinated and non-coordinated specialist contacts (table 1).

eFigure.

Flow diagram of patient selection

CFS, Chronic fatigue syndrome; FID, other functional intestinal disorder;

FM, fibromyalgia; FSS, functional somatic syndrome; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome;

SD somatoform disorder; TH, tension headache

Table 1. Patient characteristics and coordination status of the FSS group and control group in the quarter of first diagnosis or inclusion.

| Control group | FSS patients | CFS | IBS | FID | FM | TH | SD | Multiple FSS | |

| N | 50 003 | 43 676 | 20 185 | 4394 | 5618 | 720 | 6393 | 5468 | 898 |

| Age (mean in years) | 34.8 | 35.0 | 35.8 | 33.8 | 34.0 | 41.4 | 32.7 | 36.2 | 35.5 |

| Female (%) | 49.3 | 67.4 | 68.8 | 64.3 | 67.4 | 87.1 | 67.0 | 62.3 | 69.6 |

| Urban residence (%) | 48.0 | 51.2 | 51.1 | 49.9 | 50.9 | 42.4 | 50.8 | 54.5 | 51.6 |

| Previous psychological disorder (%) | 22.5 | 48.5 | 51.1 | 40.5 | 43.2 | 61.5 | 41.1 | 57.5 | 50.8 |

| PCP care only (%) | 49.5 | 30.3 | 36.7 | 26.2 | 26.4 | 13.5 | 26.7 | 21.8 | 19.8 |

| Coordinated specialist care (%) | 13.8 | 29.5 | 28.6 | 34.6 | 28.8 | 30.4 | 27.8 | 31.0 | 33.4 |

| Non-coordinated specialist care (%) | 36.6 | 40.2 | 34.7 | 39.2 | 44.8 | 56.1 | 45.6 | 47.2 | 46.8 |

CFS, Chronic fatigue syndrome; FID, other functional intestinal disorder; FM, fibromyalgia; FSS, functional somatic syndrome; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; PCP, primary care physician; TH, tension headache; SD somatoform disorder

Relative frequency of diagnostic procedures and outpatient surgery

Figure 1 displays the RR over time for diagnostic procedures and outpatient surgery, as estimated by the regression models. FSS patients exhibited higher rates of radiography, CT, MRI, and outpatient surgery than controls over the whole period (black line). The medical diagnostics and outpatient interventions followed similar patterns, with the RR peaking around the time of first diagnosis. The maxima of the risk ratios (RR) are given in Table 2. Non-coordinated FSS patients (NP) showed higher healthcare utilization than patients of the PBC group (red line). The subgroup analysis restricted to patients who visited specialists also showed higher utilization by NP than by the coordinated patients (CP) (blue line).

Figure 1.

Relative risk (RR) for the outcomes magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, radiography, and outpatient surgery, with the comparisons “FSS group versus control group” (black line), “non-coordinated specialist care (NP) versus primary care physician-based care” (red line), and “non-coordinated specialist care versus coordinated specialist care” (blue line). Bands are 95% confidence intervals. FSS, Functional somatic syndromes

Table 2. Comparison of utilization among the different groups, showing peak risk ratios (RR).

| FSS group versus control group | PBC group versus NP group | NP group versus CP group | |

| RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | |

| Radiography | 1.48 (1.46–1.50) | 1.46 (1.44–1.48) | 1.15 (1.12–1.17) |

| Computed tomography | 2.01 (1.94–2.08) | 1.82 (1.77–1.82) | 1.20 (1.14–1.26) |

| Magnetic resonance imaging | 1.91 (1.87–1.96) | 1.77 (1.74–1.81) | 1.26 (1.22–1.30) |

| Surgery | 1.30 (1.27–1.34) | 1.61 (1.56–1.65) | 1.24 (1.18–1.30) |

| Costs | 1.49 (1.48–1.50) | 1.37 (1.36–1.38) | 1.11 (1.10–1.11) |

FSS, Functional somatic syndrome; PBC, primary care physician-based care (patients treated and coordinated by their primary care physician); CP coordinated patients (treated by specialist, referral by primary care physician mandatory); NP, non-coordinated patients (treated solely by specialist, no referral)

Descriptive analysis of the individual FSS

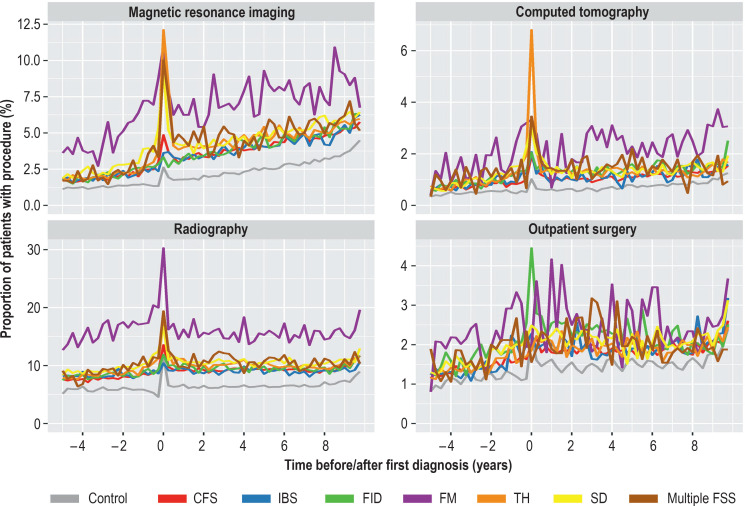

Figure 2 displays the proportion of patients in each quarter undergoing each of the medical interventions, without adjustment or smoothing. Details of the outpatient surgical procedures are shown in the eTable. Patients with fibromyalgia utilized medical interventions more often than the other groups of patients, particularly with regard to MRI and radiography, which were used considerably more frequently than CT or outpatient surgery. The peaks of diagnostic MRI and CT at the time of diagnosis in patients with tension headaches are also plainly visible.

Figure 2.

Proportions of patients undergoing the selected medical procedures in each quarter period, for the six FSS subgroups and the control group separately.

CFS, Chronic fatigue syndrome; FID, other functional intestinal disorder; FM, fibromyalgia; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; SD somatoform disorder; TH, tension headache

eTable. Summary of the outpatient surgical procedures most commonly performed on patients of the cohort.

| OPS code | OPS definition | Number of patients |

| 5–895.2a | Radical and extensive excision of diseased tissue on the skin and subcutaneous tissue, with primary wound closure: chest wall and back | 2629 |

| 5–812.5 | Arthroscopic surgery on the articular cartilage and on the menisci: partial meniscus resection | 1790 |

| 5–895.24 | Radical and extensive excision of diseased tissue on the skin and subcutaneous tissue, with primary wound closure: other parts of the head | 1761 |

| 5–690.0 | Therapeutic curettage (abrasio uteri): without application of local medication | 1450 |

| 5–215.3 | Operations on the lower nasal concha: submucosal resection | 1363 |

| 5–056.40 | Neurolysis and decompression of a nerve, nerve hand: open surgical | 1141 |

| 5–385.70 | Ligation, excision, and stripping of varices, crossectomy and stripping: great saphenous vein | 1140 |

| 5–214.6 | Submucosal resection and plastic reconstruction of the nasal septum: plastic correction with resection | 560 |

| 5–895.2e | Radical and extensive excision of diseased tissue on the skin and subcutaneous tissue, with primary wound closure: thighs and knees | 526 |

| 5–895.2g | Radical and extensive excision of diseased tissue on the skin and subcutaneous tissue, with primary wound closure: foot | 493 |

| 5–895.2b | Radical and extensive excision of diseased tissue on the skin and subcutaneous tissue, with primary wound closure: abdominal region | 493 |

| 5–895.3a | Radical and extensive excision of diseased tissue on the skin and subcutaneous tissue, with primary wound closure, histographically controlled (micrographic surgery): chest wall and back | 461 |

| 5–493.2 | Surgical treatment of hemorrhoids: excision (e.g., according to Milligan-Morgan) | 432 |

OPS, German Operations and Procedures Classification

Relative cost of ambulatory care

Figure 3 displays the relative difference in the costs of ambulatory care on the basis of the regression model. The RR are depicted in Table 2. After adjusting for potential confounders, the FSS patients were found to incur higher costs than the controls throughout the period from 5 years before diagnosis to 10 years thereafter (black line). The non-coordinated patients incurred higher costs than those of the PBC group throughout, beginning four years before diagnosis (red line). In the subgroup analysis of patients with specialist contacts, the NP group also incurred higher costs than the CP group (blue line).

Figure 3.

Relative increase in cost of ambulatory care, with the comparisons “FSS group versus control group” (black line), “non-coordinated specialist care (NP) versus primary care physician-based care” (red line), and “non-coordinated specialist care versus coordinated specialist care” (blue line). Bands are 95% confidence intervals. FSS, Functional somatic syndromes

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the healthcare utilization of a broad spectrum of FSS patients over a period of 15 years in outpatient care. We found that FSS patients undergo imaging procedures and outpatient surgery more frequently than patients without FSS. The extent of this utilization was greater among patients whose specialist care was not coordinated by a primary care physician.

The increased utilization of imaging modalities and surgery is of particular concern because of the inherent risk of harm to the patients. It is well known that repeated diagnostic radiography and CT is associated with an increased risk of cancer (23). Outpatient surgery involves the risk of infections or iatrogenic lesions. Our analyses extend the findings from hospital settings (8– 12) to the ambulatory sector in a large patient cohort. These effects were shown to persist over the whole period, commencing long before the diagnosis of FSS was first documented. Furthermore, the impact of expensive diagnostic procedures and surgery on outpatient healthcare costs became clear.

Peak rates of diagnostic procedures were found at the time of diagnosis could be explained by interventions to rule out organic diseases. Since the increased utilization was found throughout the period in question, however, it appears still to be challenging to identify these vulnerable patients in time to prevent somatic fixation and overdiagnosis. Implementation of the treatment strategies and concepts of patient management described at the beginning of this article (4, 15–17) requires a „holistic“ biopsychosocial understanding of patients, based on a longstanding and trusting doctor–patient relationship. These aspects are stressed as core values of general practice and family medicine (18, 19, 24). Correspondingly, we showed that lower healthcare utilization was associated with coordination of care by the primary care physician. The effect does not seem to be very large at first sight. However, its magnitude is in line with the effects of other population-based analyses that have investigated the impact of continuity of care and of the holistic provision of patient care (25, 26). Nevertheless, the increased utilization of potentially harmful interventions appears to indicate a deficiency in care. Further efforts are therefore necessary to develop and evaluate effective communication and treatment strategies in ambulatory care, with the aim of improving the long-term prognosis of patients with FSS.

Strengths and limitations of the study

A major strength of the present study is the opportunity to analyze a large, representative billing database with reliable observation of anonymized patients over a period of 15 years. A limitation is that the FSS group had a higher proportion of female patients and a higher rate of previous psychological disorders than the control group; this effect was doubly accounted for in the regression model by means of weighting processes and adjustments. Moreover, the diagnoses used were those recorded by the physicians and psychotherapists at the time of first treatment, minimizing risks such as recall bias. The use of routine data could also be viewed as a limitation, because the medical information content is restricted to the documented ICD-10 diagnoses, which in turn are subject to the peculiarities of the reimbursement system and the physicians’ coding practices. Cohort selection was therefore based on the clinical judgment of the individual physicians and not on a standardized test or a scientifically objective diagnostic classification. Another limitation is that we could consider only the coordination status in the quarter of first diagnosis, because the allocation of each patient to a single coordination group simplifies the analysis and interpretation of the data compared with incorporation of time-dependent variables. However, the time of first diagnosis represents a particularly critical stage in the disease history at which coordinated care is of special importance. Furthermore, only FSS patients with repeated consultations could be included for analysis. Patients with a single contact may represent less severe forms of FSS, but no conclusions can be drawn on this point. Moreover, we had no information about interventions in the hospital setting. This may have led to underestimation of the utilization of medically harmful procedures by patients with FSS.

Conclusion

Patients with FSS exhibit increased utilization of potentially harmful diagnostic investigations and outpatient surgical procedures. Coordination by primary care physicians and continuity of care should be strengthened to enable early identification of these vulnerable patients and facilitate ambulant care management.

Supplementary Material

eMethods

Study data

The data are analyzed with respect to the services billed by the office-based physicians consulted during this period. The study was conducted according to the German guideline “Good Practice of Secondary Data Analysis” (e1).

The data cover approximately 85% of the population of Bavaria (2010: 10.4 million people with statutory health insurance) and are submitted by primary care physicians, office-based specialists, and psychotherapists primarily for the primary purpose of remuneration.

Primary care physicians account for 43% of all ambulatory physicians. Statutory health insurance funds pay a fixed amount to the federal states’ Associations of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians, which then remunerate physicians for each quarter of a year based on a system that combines bundled payments with fee-for-service reimbursement.

Ambulatory services and procedures are billed according to the German Physicians’ Fee Schedule (Einheitlicher Bewertungsmaßstab, EBM), which lists a fixed quarterly amount plus additional fees for defined diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Outpatient surgery is billed according to the German Classification of Operations and Procedures (OPS). All diagnoses relevant for the treatment episode are documented using the German modification of the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition (ICD-10-GM).

In Germany, outpatient radiological centers usually perform diagnostic and curative interventions after referral by an office-based specialist or primary care physician. We included the following diagnostic procedures, all billed according to section 34 of the EBM: magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), and radiography. Routine screening mammography was excluded.

The database allocates a unique and persistent pseudonym to each patient, removing all person-related information (name, insurance number, exact date of birth and address, etc.) in order to conceal the identity of the patients. Emergency cases, obstetrics, routine screening mammography and radiological testing (i.e., services billed by a radiologist for medical imaging) were not considered when determining the coordination status. This approach has been explained and analyzed in previous publications that used the same database (e2, e3).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted in three stages. First, the patients in each group were described with respect to demographic and other selected variables, together with the length of the follow-up period. This was performed without weighting in order to highlight differences among the groups with regard to the distribution of age, sex, and place of residence. Next, the patients’ quarterly claims were analyzed using descriptive and graphical methods. Of interest were both the status in the quarter of first diagnosis and the average development of utilization per quarter. Patients without consultation in a given quarter were included with zero costs and no utilization. In a third stage, the longitudinal regression models were fitted to the outcomes of interest for each quarterly billing period. A generalized estimating equation (GEE) approach was used to account for intrapatient autocorrelation, assuming a first-order autoregressive variance structure.

The models incorporated the age and sex of the patient as well as the area of residence, categorized using a four-level classification ranging from “large city” to “sparsely populated rural area” provided by the Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs, and Spatial Development (21). To ensure comparability of the groups, in the regression model all FSS patients were weighted so that the distribution by age, sex, and area of residence corresponded to the Bavarian population aged 18 to 50 years in 2010. This was necessary to control for differences in regional healthcare utilization. Charlson comorbidities (22) were calculated for the year prior to first diagnosis and and incorporated into the regression model to control for pre-existing somatic conditions. Previous psychological disorder, defined as a confirmed diagnosis of depression (ICD-10 code F32 or F33), anxiety (F41), or stress disorder (F43), was included as a further relevant comorbidity.

Two comparisons were relevant and were carried out using variants of the above model. First, to ascertain whether patients with FSS experience excess utilization, they were compared with a control group with no documented diagnosis of FSS. The predictor of interest was a dummy variable denoting the case patients. Second, in order to compare cases with and without coordination of care, the control patients were excluded and the coordination status (“primary care physician only,” “coordinated specialist treatment,” or “non-coordinated specialist treatment”) was included as predictor. For each patient, the inclusion of smooth additive terms enabled the estimation of time-varying parameters to assess how the effect of the diagnosis FSS (first comparison) or of primary care physician-based care (second comparison) changes over time.

The models were applied to predict the quarterly costs and event probabilities for a typical patient: a 30-year-old woman with irritable bowel syndrome, living in a city, with no previous psychological disorder and no documentation of a Charlson comorbidity. The covariables of interest were varied (i.e., patient group/control group, coordinated/non-coordinated, with and without psychological disorder). Relative risks with 95% posterior confidence intervals were calculated to assess the time-varying effects of the variables “FSS patient” and “coordination of care” (e4). The statistical analyses were carried out by the statistician ED using R (version 3.6.1) with the mgcv package for regression modeling.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the support of the Bavarian Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians in providing access to the study data.

Statement of Ethics

The analysis was conducted In line with the German guideline for research ”Good Practice of Secondary Data Analysis” (Gute Praxis Sekundärdaten) using an anonymized dataset. Accordingly, ethics committee approval and patient consent were not required. The study was conducted in strict adherence to data protection regulations as mandated by the data holder (Bavarian Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Haller H, Cramer H, Lauche R, Dobos G. Somatoform disorders and medically unexplained symptoms in primary care—a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:279–287. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2015.0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burton C, Fink P, Henningsen P, et al. Functional somatic disorders: discussion paper for a new common classification for research and clinical use. BMC Med. 2020;18 doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-1505-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Löwe B, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. Depression, anxiety and somatization in primary care: syndrome overlap and functional impairment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henningsen P, Zipfel S, Herzog W. Management of functional somatic syndromes. Lancet. 2007;369:946–955. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barsky AJ, Orav EJ, Bates DW. Distinctive patterns of medical care utilization in patients who somatize. Med Care. 2006;44:803–811. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000228028.07069.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider A, Hilbert S, Hamann J, et al. The implications of psychological symptoms for length of sick leave—burnout, depression, and anxiety as predictors in a primary care setting. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114:291–297. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katerndahl DA, Bell IR, Palmer RF, Miller CS. Chemical intolerance in primary care settings: prevalence, comorbidity, and outcomes. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:357–365. doi: 10.1370/afm.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fink P. Surgery and medical treatment in persistent somatizing patients. J Psychosom Res. 1992;36:439–447. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(92)90004-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kouyanou K, Pither CE, Wessely S. Iatrogenic factors and chronic pain. Psychosom Med. 1997;59:597–604. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199711000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cole JA, Yeaw JM, Cutone JA, et al. The incidence of abdominal and pelvic surgery among patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:2268–2275. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-3047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu CL, Liu CC, Fuh JL, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome and negative appendectomy: a prospective multivariable investigation. Gut. 2007;56:655–660. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.112672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaufman EL, Tress J, Sherry DD. Trends in medicalization of children with amplified musculoskeletal pain syndrome. Pain Med. 2017;18:825–831. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnw188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schaefert R, Kaufmann C, Wild B, et al. Specific collaborative group intervention for patients with medically unexplained symptoms in general practice: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2013;82:106–119. doi: 10.1159/000343652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lehmann M, Jonas C, Pohontsch NJ, et al. General practitioners views on the diagnostic innovations in DSM-5 somatic symptom disorder—a focus group study. J Psychosom Res. 2019;123 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.109734. 109734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gask L, Dowrick C, Salmon P, et al. Reattribution reconsidered: narrative review and reflections on an educational intervention for medically unexplained symptoms in primary care settings. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71:325–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henningsen P, Zipfel S, Sattel H, Creed F. Management of functional somatic syndromes and bodily distress. Psychother Psychosom. 2018;87:12–31. doi: 10.1159/000484413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roenneberg C, Sattel H, Schaefert R, Henningsen P, Hausteiner-Wiehle C. Clinical practice guideline: functional somatic symptoms. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019;116:553–560. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Organization of National Colleges, Academies and Academic Associations of General Practitioners/Family Physicians (WONCA) The European definition of general practice/family medicine. %%%%%%% www.woncaeurope.org/file/520e8ed3-30b4-4a74-bc35-87286d3de5c7/Definition%203rd%20ed%202011%20with%20revised%20wonca%20tree.pdf (last accessed on 25 January 2021) 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin (DEGAM) Die Fachdefinition der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin. www.degam.de/fachdefinition.html (last accessed on 25 January 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneider A, Hilbert B, Hörlein E, Wagenpfeil S, Linde K. The effect of mental comorbidity on service delivery planning in primary care: an analysis with particular reference to patients who request referral without prior assessment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110:653–659. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bundesinstitut für Bau-, Stadt- und Raumforschung (BBSR) Siedlungsstrukturelle Kreistypen. www.bbsr.bund.de/BBSR/DE/startseite/_node.html (last accessed on 25 January 2021) 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armitage JN, van der Meulen JH Royal College of Surgeons Co-morbidity Consensus Group. Identifying co-morbidity in surgical patients using administrative data with the royal college of surgeons charlson score. Br J Surg. 2010;97:772–781. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffey RT, Sodickson A. Cumulative radiation exposure and cancer risk estimates in emergency department patients undergoing repeat or multiple CT. Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:887–892. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Starfield B, Shi L, MacInko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83:457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, Franks P. The cost of satisfaction. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:405–411. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Phillips RL, Bitton A, Landon BE, Phillips RS. Association of primary care physician supply with population mortality in the United States, 2005-2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:506–514. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Swart E, Gothe H, Geyer S, et al. German Society for Social Medicine and Prevention; German society for Epidemiology. Good practice of secondary data analysis (GPS): guidelines and recommendations. Gesundheitswesen. 2015;77:120–126. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1396815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Donnachie E, Schneider A, Enck P. Comorbidities of patients with functional somatic syndromes before, during and after first diagnosis: a population-based study using Bavarian routine data. Sci Rep. 2020;10 doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66685-4. 9810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Donnachie E, Schneider A, Mehring M, Enck P. Incidence of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic fatigue following GI infection: a population-level study using routinely collected claims data. Gut. 2018;67:1078–1086. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-313713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Wood S. Generalized additive models: An Introduction with R 2nd ed. Chapman and Hall/CRC Press. www.routledge.com/Generalized-Additive-Models-An-Introduction-with-R-Second-Edition/Wood/p/book/9781498728331. (last accessed on 17 November 2020) 2017 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

Study data

The data are analyzed with respect to the services billed by the office-based physicians consulted during this period. The study was conducted according to the German guideline “Good Practice of Secondary Data Analysis” (e1).

The data cover approximately 85% of the population of Bavaria (2010: 10.4 million people with statutory health insurance) and are submitted by primary care physicians, office-based specialists, and psychotherapists primarily for the primary purpose of remuneration.

Primary care physicians account for 43% of all ambulatory physicians. Statutory health insurance funds pay a fixed amount to the federal states’ Associations of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians, which then remunerate physicians for each quarter of a year based on a system that combines bundled payments with fee-for-service reimbursement.

Ambulatory services and procedures are billed according to the German Physicians’ Fee Schedule (Einheitlicher Bewertungsmaßstab, EBM), which lists a fixed quarterly amount plus additional fees for defined diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Outpatient surgery is billed according to the German Classification of Operations and Procedures (OPS). All diagnoses relevant for the treatment episode are documented using the German modification of the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition (ICD-10-GM).

In Germany, outpatient radiological centers usually perform diagnostic and curative interventions after referral by an office-based specialist or primary care physician. We included the following diagnostic procedures, all billed according to section 34 of the EBM: magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), and radiography. Routine screening mammography was excluded.

The database allocates a unique and persistent pseudonym to each patient, removing all person-related information (name, insurance number, exact date of birth and address, etc.) in order to conceal the identity of the patients. Emergency cases, obstetrics, routine screening mammography and radiological testing (i.e., services billed by a radiologist for medical imaging) were not considered when determining the coordination status. This approach has been explained and analyzed in previous publications that used the same database (e2, e3).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted in three stages. First, the patients in each group were described with respect to demographic and other selected variables, together with the length of the follow-up period. This was performed without weighting in order to highlight differences among the groups with regard to the distribution of age, sex, and place of residence. Next, the patients’ quarterly claims were analyzed using descriptive and graphical methods. Of interest were both the status in the quarter of first diagnosis and the average development of utilization per quarter. Patients without consultation in a given quarter were included with zero costs and no utilization. In a third stage, the longitudinal regression models were fitted to the outcomes of interest for each quarterly billing period. A generalized estimating equation (GEE) approach was used to account for intrapatient autocorrelation, assuming a first-order autoregressive variance structure.

The models incorporated the age and sex of the patient as well as the area of residence, categorized using a four-level classification ranging from “large city” to “sparsely populated rural area” provided by the Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs, and Spatial Development (21). To ensure comparability of the groups, in the regression model all FSS patients were weighted so that the distribution by age, sex, and area of residence corresponded to the Bavarian population aged 18 to 50 years in 2010. This was necessary to control for differences in regional healthcare utilization. Charlson comorbidities (22) were calculated for the year prior to first diagnosis and and incorporated into the regression model to control for pre-existing somatic conditions. Previous psychological disorder, defined as a confirmed diagnosis of depression (ICD-10 code F32 or F33), anxiety (F41), or stress disorder (F43), was included as a further relevant comorbidity.

Two comparisons were relevant and were carried out using variants of the above model. First, to ascertain whether patients with FSS experience excess utilization, they were compared with a control group with no documented diagnosis of FSS. The predictor of interest was a dummy variable denoting the case patients. Second, in order to compare cases with and without coordination of care, the control patients were excluded and the coordination status (“primary care physician only,” “coordinated specialist treatment,” or “non-coordinated specialist treatment”) was included as predictor. For each patient, the inclusion of smooth additive terms enabled the estimation of time-varying parameters to assess how the effect of the diagnosis FSS (first comparison) or of primary care physician-based care (second comparison) changes over time.

The models were applied to predict the quarterly costs and event probabilities for a typical patient: a 30-year-old woman with irritable bowel syndrome, living in a city, with no previous psychological disorder and no documentation of a Charlson comorbidity. The covariables of interest were varied (i.e., patient group/control group, coordinated/non-coordinated, with and without psychological disorder). Relative risks with 95% posterior confidence intervals were calculated to assess the time-varying effects of the variables “FSS patient” and “coordination of care” (e4). The statistical analyses were carried out by the statistician ED using R (version 3.6.1) with the mgcv package for regression modeling.