Abstract

Air spaces and material surfaces in a pathogen-contaminated environment can often be a source of infection to humans, and disinfection has become a common intervention focused on reducing the contamination levels. In this study, we examined the efficacy of SAIW, a unique electrolyzed water with chlorine-free, high pH, high concentration of dissolved hydrogen, and low oxygen reduction potential, for the inactivation of several viruses and bacteria. Infectivity assays revealed that initial viral titers of enveloped and non-enveloped viruses, including severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), influenza A virus, herpes simplex virus type 1, human coronavirus, feline calicivirus, and canine parvovirus, were reduced by 2.9- to 5.5-log10 within 30 s of SAIW exposure. Similarly, the culturability of three Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli, Salmonella, and Legionella) dropped down by 1.9- to 4.9-log10 within 30 s of SAIW treatment. Mechanistically, treatment with SAIW was found to significantly decrease the binding and subsequent entry efficiencies of SARS-CoV-2 on Vero cells. Finally, we showed that this chlorine-free electrolytic ion water had no acute inhalation toxicity in mice, demonstrating that SAIW holds promise for a safer antiviral and antibacterial disinfectant.

Keywords: SAIW, Disinfection, Chlorine-free, Enveloped and non-enveloped viruses, Glam-negative bacteria, SDGs

1. Introduction

Viruses and bacteria are common causes of infectious diseases that occur in indoor environments such as hospitals, schools, homes, and public transportations [1] and hence, have enormous impacts on human health. For instance, viruses are currently responsible for about 60% of human infections, and the most common illnesses are caused by respiratory and gastrointestinal viruses [2,3]. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), a novel betacoronavirus, has created economic and social turmoil worldwide [4]. COVID-19, which is caused by SARS-CoV-2, has been shown to be associated with severe symptoms such as acute respiratory distress syndrome, vasculitis, thrombosis, stroke, myocardial damage, and multiple organ failure, including acute renal failure [5,6]. Many people also suffer from other respiratory viruses such as influenza virus in the cold season, which can cause various respiratory disorders, from a mild inflammation of the upper respiratory tract to acute pneumonia, potentially leading to the death of the patient [4]. Also, human coronavirus OC43 (HCoV-OC43) causes upper respiratory tract symptoms in the nose and throat [7]. Additionally, herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) causes oral herpes infection mainly through contact with HSV-1 present around the oral cavity or in the wound, saliva, and skin surface [8]. In contrast, inactivation of enteric viruses such as norovirus and parvovirus, which do not have an envelope with rubbing alcohol or an organic solvent, is more difficult than enveloped viruses [9,10].

Gram-negative bacteria are also composed of clinically important pathogens [11]. Certain Escherichia coli (E. coli) strains cause infections in the digestive tract, urinary tract, and other parts of the body. E. coli infections occur in the intestines due to eating contaminated food, touching infected animals, or swallowing contaminated water in pools, causing diarrhea and abdominal pain, sometimes with severe bleeding. Legionella spp. inhabits natural environments, and its host ameba grows in artificial water-circulation equipment such as fountains, in which large amounts of Legionella exist. Salmonella inhabits the intestines of humans, cattle, pigs, chickens, and other livestock, as well as the natural world (rivers and sewage). Thus, meat, including beef, pork, chicken, and fish, are also the sources of these Gram-negative bacterial contaminations.

Antibiotics, antivirals, and vaccines remain unavailable against many of the respiratory and intestinal pathogens. Therefore, those spreads could be stopped by disinfectants, which have long been used as a highly effective means for protecting vulnerable people from infectious diseases in general environments, particularly in hospitals and care homes [12]. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends chlorine (sodium hypochlorite) as a disinfectant in infection control (https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/clinicians/non-us-healthcare-settings/chlorine-use.html). However, chlorine is corrosive, has a pungent odor, and may not be practical for long-term use due to potential health hazards. In this study, we evaluated SAIW (Super Alkaline Ionized Water) as a novel disinfectant for the inactivation of various enveloped and non-enveloped viruses and Gram-negative bacteria. SAIW is an alkaline electrolyzed water that does not use chlorine-based chemicals. Importantly, SAIW contains only a minimal amount of potassium hydroxide (KOH), and it can be readily returned into plain water or salt water by dilution. Furthermore, SAIW is colorless and transparent, odorless, and rust-free, indicating its potential to be an eco-friendly disinfecting material. As expected, SAIW showed strong antiviral and antibacterial effects with an extremely short contact time. Mechanistically, SAIW treatment markedly suppressed the binding and entry efficiency of SARS-CoV-2 to target cells. Additionally, in vivo safety in the use of SAIW on animals and humans was also demonstrated.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation of the SAIW

To generate SAIW, tap water was purified using reverse osmosis (RO) membrane to remove impurities and electrolyzed in the presence of food-grade potassium carbonate as an electrolyte and a cation exchange diaphragm in an electrolyzed chamber that separates the anode and cathode. In the procedure, SAIW was obtained from the cathode. In this study, the amount of raw water supplied to the cathode chamber of the electrolytic cell was made smaller than the amount of raw water, and strong electrolytic ionized water with a pH value higher than the reference pH value was produced (JP2014/069980).

2.2. Cells and viruses

All cell cultures were maintained at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2. Vero E6/TMPRSS2 and MRC (human fetal fibroblast, ATCC CCL-171) cells were maintained with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). MDCK (NBL-2, canine kidney, Health Science Research Resources Bank JCRB 9029), HEp-2 (human larynx carcinoma, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd.), and CRFK (Crandell-Reese feline kidney, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd.) cell lines were cultured using Eagle's minimum essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% FBS. In some experiments using canine parvovirus (CPV), the CRFK cell was maintained using DMEM containing 10% FBS.

Two clinical isolates of SARS-CoV-2 (19–865 [GenBank Accession No. LC546038.1] and OMC-510 [GenBank Accession No. LC633518]) were obtained from COVID-19 patients and amplified with Vero E6/TMPRSS2 cells. The propagation of influenza A virus (H1N1 A/PR/8/34 [ATCC VR-1469]) and HSV-1 (KOS [ATCC VR-1493]) was performed using MDCK and HEp-2 cells, respectively. HCoV-OC43 (ATCC VR-759) was propagated in MRC, and virus infectivity was titrated by plaque formation assay. Feline calicivirus (FCV F-9 [ATCC VR-782]) and CPV (maintained at Kitasato Research Center for Environmental Sciences, Japan) were propagated using CRFK cells.

The infectivity of viruses was determined conventionally either via the plaque-forming assay (for SARS-CoV-2) or the 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) assay using the Reed-Muench formula (for influenza virus, HSV-1, HCoV-OC43, FCV, and CPV) using appropriate cells.

2.3. Antiviral assays

SARS-CoV-2 (19–865) sample was treated with a 10-fold volume of SAIW or sterilized water. After 30 s or 2 min of incubation, the mixture was diluted 10-fold with DMEM containing 10% FBS, and the diluted solution was inoculated to Vero E6/TMPRSS2 cells seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 5 × 104/well. Two hours after infection, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and cultured with DMEM containing 10% FBS. To measure the level of SARS-CoV-2 replication, viral RNA was extracted from the culture supernatant 48 h after infection and subjected to quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis using the primer/probe sets specific to the nucleocapsid region of the SARS-CoV-2 genome [13].

Treatments of other viruses with SAIW were carried out by mixing SAIW (or sterilized water) with virus samples at a ratio of 10:1 (except for HCoV-OC43 and CPV) for 30 s to 5 min at room temperature. After incubation, the mixture was diluted 10-fold with the culture medium (except for CPV) to neutralize the reaction and inoculated into respective culture cells to determine the viral titer using TCID50 assay.

As for HCoV-OC43, 30 μl of a serial dilution of the virus sample with DMEM containing 0.2% FBS was mixed with 30 μl of SAIW. After incubation, 180 μl of SCDLP medium was added to neutralize the reaction, and 100 μl of the mixture was added to MRC5 cells in a 96-well plate. One hour after exposure, cells were washed with PBS and cultured with DMEM supplemented with 0.2% FBS. Cell death caused by HCoV-OC43 infection was analyzed 96 h after infection by fixing the cells with methanol and subsequent staining with methylene blue.

The antiviral assay of CPV was performed by mixing 100 μl of the virus sample with 900 μl of SAIW. After incubation, the mixture was diluted 10-fold with a 200 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7, to neutralize the reaction. Serial dilution of the mixture was prepared using PBS, and 50 μl of the dilution was inoculated to CRFK cells with DMEM containing 5% FBS. The viral titer was determined to be TCID50 according to the viral hemagglutination activity of culture supernatants seven days after infection.

2.4. Plaque reduction assay

Twenty-five microliters of SARS-CoV-2 (OMC-510) containing 2.5 × 105 PFU virus was incubated with 225 μl of SAIW (or sterilized water) for 30 s to 5 min at room temperature. After incubation, the mixture was neutralized with 30 μl of DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Then 200 μl of a 10-times serial dilution of the mixture was subjected to plaque-forming assay.

2.5. Binding and entry assay

Twenty-five microliters of SARS-CoV-2 containing 1.25 × 106 PFU virus was incubated with 225 μl of SAIW (or sterilized water) for 2 min at room temperature and then added to the Vero E6/TMPRSS2 cell culture (seeded in a 6-well plate at a density of 5 × 105/well one day before assay) with 2 ml of DMEM for 2 h on ice (binding) or at 37 °C (entry). After exposure, cells were washed three times with cold PBS to remove unbound or uninternalized viruses. Then, total RNA was extracted, and cell-associated SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected via RT-qPCR.

2.6. Antibacterial activity

After treating 100 μl of E. coli (NBRC 3972) or Legionella pneumophila (L. pneumophila, GIFU 9134) solution with 10 ml of SAIW at 20 °C for the 30 s to 15 min, the number of viable cells was determined as colony-forming units (CFU)/ml. For the measurement of live bacteria, a flat plate smear culture method (35 °C, seven days) using a B-CYEα agar medium (EIKEN) was used. It was confirmed in advance that the viable cell count could be measured without being affected by the sample by diluting the test solution 10-fold with the medium.

For Salmonella enterica subsp. arizonae (S. arizonae, ATCC 13314), 100 μl of the bacterial solution was added to 10 ml of SAIW, and the mixture was treated at 20 °C for 30 s to 15 min. Then, 1 ml of each mixture was passed through a membrane filter (0.45 μm diameter) and washed with sterile purified water. This filter paper was brought into close contact with the nutrient agar medium and cultured at 35 °C for two days, and the viable cell number per ml was measured as CFU/ml. The same operation was performed using 150 ppm sodium hypochlorite as the positive control.

2.7. Acute inhalation toxicity

Ten ICR mice (five males and five females) were subjected to whole-body exposure to undiluted SAIW solution in a 0.5 m3 (H120 x D60 x W70 cm) experimental tank according to the method of Yamashita et al. [14]. Mice were housed in cages made of wire mesh placed in the center of the laboratory tank. The exposure was performed using an ultrasonic humidifier at a strong setting in the following order: 1) spraying was performed three times for 20 s each at 10 min intervals, 2) a recovery time of 30 min was provided, 3) additional 20 s spraying was performed three times at 10 min intervals, and 4) 10 min later, 20 s spraying was performed four times at 5 min intervals. After exposure, life and death and general condition were monitored for 14 days, during which time the body weight and food intake were measured. Then, an autopsy was performed for the macroscopic observation of various organs and the histopathological examination of the lungs. This study was conducted properly in accordance with the Animal Care and Use Code of the Drug Safety Testing Center, Yoshimi, Saitama, Japan.

2.8. Skin-patch test

The subjects enrolled were 22 Japanese adults (17 females and 5 males, 20–60 years old when they agreed to the test). The method used was a 24-h closed patch test, and the observation period was three days [15]. A skin-test patch tape was filled with an appropriate amount of the test solution (approximately 0.03 ml) and attached to the back of the subject; 24 h later, a photo was taken with a digital camera, and a doctor evaluated the skin according to the criteria (1 and 24 h after peeling). Saline and white petrolatum were applied as controls.

This study design complied with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethical committee of SOUKEN Co Ltd (Tokyo, Japan). Written informed consent was obtained from each volunteer before the patch test. The volunteers were fully explained in advance that they were free to participate in this study and that they would not be disadvantaged if they disagreed. The volunteers’ health statuses, including no past severe medical histories or dermal diseases, were confirmed prior to performing the patch test.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of a novel electrolyzed water, SAIW

SAIW prepared in this study (termed e-WASH) was electrolyzed alkaline water with a high concentration of dissolved hydrogen, and its components were 99.83% water and 0.17% KOH. Immediately after production, the SAIW contained no free chlorine (under the limit of detection), and its oxygen reduction potential, dissolved hydrogen concentration, and pH values were −700 to −900 mV, 423 ppb, and 12.5 (about ±3%), respectively. The average pH of SAIW was almost the same level for 180 days and more when sealed, and 48 days or more when released.

3.2. Inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 by SAIW

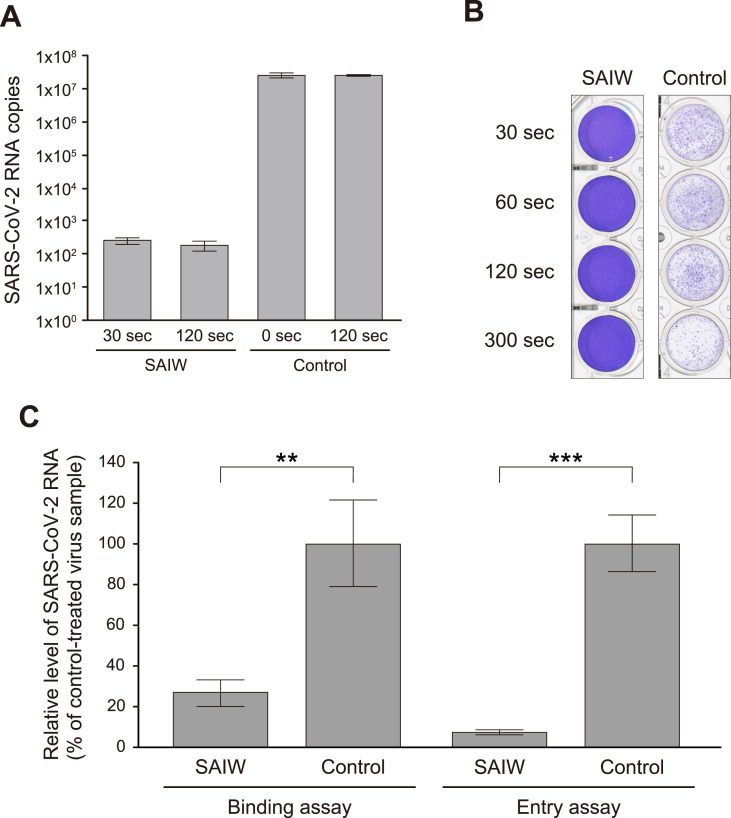

First, the effect of SAIW treatment on the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 was investigated. When Vero E6/TMPRSS2 cells were inoculated with SARS-CoV-2 that had been treated with a 10-fold volume of SAIW for 2 min, the level of viral RNA detected in the culture supernatant at 48 h after infection was reduced by 5-log10 compared to sterilized water (control)-treated virus samples (Fig. 1 A). Since the exposure with SAIW was speculated to inactivate the composition of the virion surface, a plaque-reduction assay of the SAIW-treated virus was performed next. Fig. 1B shows that even after 30 s treatment, plaques formed by SARS-CoV-2 infection were not observed, whereas many plaques were obtained after pretreatment with sterilized water.

Fig. 1.

Inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 infectivity by SAIW. (A) Replication assay. SARS-CoV-2 was exposed with a 10-fold volume of SAIW or sterilized water (control) for 30 s (sec) to 2 min (120 sec) and added to Vero E6/TMPRSS2 cells. Replication of SARS-CoV-2 was evaluated by measuring the viral RNA level via RT-qPCR analysis using the primer/probe sets specific to the nucleocapsid region of the viral genome. (B) Plaque reduction assay. SARS-CoV-2 was treated with SAIW or sterilized water (control) for 30 s to 5 min (300 sec) and subjected to a plaque-forming assay using Vero E6/TMPRSS2 cells. Representative images of plaque formation two days after exposure are shown. (C) Binding and entry assay. SARS-CoV-2 was mixed with SAIW or sterilized water (control) at a ratio of 1:9 for 2 min and added to Vero E6/TMPRSS2 cells on ice (binding assay) or at 37 °C (entry assay). After 2 h, cells were washed with cold PBS three times, and immediately after washing, total RNA was isolated. Cell-associated SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected via RT-qPCR analysis. The average values from three independent experiments are shown with error bars indicating the standard deviation. Statistical significance was determined by Student's t-test JMP Pro software (SAS Institute): ∗∗, P < 0.01; ∗∗∗, P < 0.001. P-values below 0.05 were considered significant.

We also assessed the efficiency of virus binding and entry steps [16]. Vero E6/TMPRSS2 cells were exposed with SAIW- and control-treated SARS-CoV-2 on ice (binding assay) or at 37 °C (entry assay) for 2 h, and after washing with cold PBS, cell-associated viral RNA was detected by RT-qPCR. The result showed that, when compared with control, SAIW treatment significantly decreased the efficiency of virus binding and subsequent entry processes (Fig. 1C). Taken together, these data indicated that SAIW treatment limited the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2, likely via the induction of a near-complete loss of the cell attachment activity of viruses.

3.3. Antiviral activities against other enveloped and non-enveloped viruses

The efficacy of SAIW for the inactivation of three enveloped (influenza A virus, HSV-1, and HCoV-OC43) and two non-enveloped (FCV and CPV) viruses were also tested. As shown in Table 1 , infectivity reductions of 5.5-, 3.5-, 4.5-, 4.5-, and 2.9-log10 PFU/ml or TCID50/ml were achieved after 30 s treatment with SAIW in influenza A virus, HSV-1, HCoV-OC43, FCV, and CPV, respectively.

Table 1.

Inhibitory effect of SAIW against infectivity of various enveloped and non-enveloped viruses a.

| Viruses | Treatment | Time of exposure (seconds) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 30 | 120 | 180 | 300 | |||

| Enveloped | Influenza A virus H1N1 A/PR/8/34 | Control | 1 × 107 | – b | 1 × 107.3 | – | – |

| SAIW | – | <32 c | <32 | – | – | ||

| Herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1) KOS | Control | 1 × 105 | – | 1 × 105.8 | – | – | |

| SAIW | – | <32 c | <32 | – | – | ||

| Human coronavirus (HCoV) OC43 | Control | 1 × 106 | – | – | – | – | |

| SAIW | – | <32 c | <32 | – | – | ||

| Non-enveloped | Feline calicivirus (FCV) F9 | Control | 1 × 106 | – | – | – | 1 × 105.7 |

| SAIW | – | <32 c | – | – | <32 | ||

| Canine parvovirus (CPV) | Control | 6.3 × 104 | – | – | 6.2 × 104 | – | |

| SAIW | – | 72 | <63c | – | – | ||

Viral titers were determined by TCID50/ml.

Not tested.

Below the limit of detection.

3.4. Antibacterial activities

The antibacterial effects of SAIW were examined by cultivating bacteria on soft agar. Thirty-second exposure of three Gram-negative bacterial strains with SAIW resulted in 4.9-, 1.9-, and 2.4-log10 reduction in E. coli, S. arizonae, and L. pneumophila suspensions, respectively (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Inhibitory effect of SAIW on viability of Gram-negative bacteria a.

| Bacteria | Treatment | Time of exposure (seconds) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 30 | 300 | 900 | ||

| Escherichia coli | Control | 8.6 × 105 | – b | – | 1.1 × 106 |

| SAIW | – | <10 c | <10 | <10 | |

| Salmonella arizonae | Control | 7.6 × 102 | – | – | – |

| SAIW | – | <10 c | <10 | <10 | |

| Legionella pneumophila | Control | 1.4 × 107 | – | – | 2.0 × 107 |

| SAIW | – | 5.9 × 104 | <100 c | <100 | |

Viable bacterial cells were determined as CFU/ml.

Not tested.

Below the limit of detection.

3.5. Acute inhalation toxicity of SAIW in mice

When we examined acute inhalation toxicity of SAIW using ICR mice, neither abnormalities nor deaths were observed in the 5 male and 5 female mice. In terms of body weight, a decrease was seen in four of the five males (0.2, 0.4, 0.5, and 0.8 g), while one of the five females showed a decrease (0.4 g) 1 day after exposure. The average reduction was 0.25 g, with a range of 0.2–0.8 g. However, these mice also showed weight gain 2 or 3 days after exposure. The average increase over 14 days was 6.58 g for males and 4.86 g for females, showing the same tendency as in the control mice. After 14 days, there was no weight difference in unexposed mice. During the study period, male food intake was 4.2–5.4 g/animal/day, and female intake was 3.8–4.4 g/animal/day, the same as in the control mice. No abnormality in autopsy and no change were seen in either sex in histopathological examination.

3.6. Skin-patch test in humans

Human volunteers between the ages of 20 and 60 were subjected to a closed patch test by continuous application of SAIW and the control for 24 h. The skin irritation index was confirmed to be zero in all volunteers.

4. Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that a unique electrolyzed water SAIW was a safe disinfectant effective to enveloped and non-enveloped viruses and Gram-negative bacteria. So far, the antibacterial effect of acidic electrolyzed water has been primarily studied, and many of them focused on the effect of free available chlorine (FAC) in the electrolyzed water [17,18]. Recently, it was reported that a neutral electrolyzed water (pH 7) reduced human norovirus RNA copy by 4.8-log10 after suspension for 1 min in the presence of 250 ppm FAC [19]. Additionally, Bui et al. showed strong virucidal activity against the foot-and-mouth disease virus by using alkaline electrolyzed water (pH 12.1) containing 1.0 ppm FAC, suggesting that the effect is independent of chlorine levels in solution [20]. One of the distinguishing features of SAIW is that this electrolyzed water does not contain any chlorine-based chemicals. Furthermore, SAIW is colorless, odorless, transparent, nonirritating, and non-corrosive. It easily reverts to water or salt water by dilution, making SAIW extremely environmentally friendly. Additionally, SAIW is chemically stable for long periods (several months or more). SAIW generators are commercially available and have the advantage that they can easily be used to produce on-site fresh electrolytic water using tap water and potassium carbonate, contributing to the preparation for disaster prevention in an emergency. Given its in vivo safety profile presented in this study, SAIW is expected to be used in the form of not only soak and cleaning solution but also disinfectant in places where the use of alcohol is not allowed.

It is interesting to explore how SAIW inactivates viruses and bacteria. The denaturation mechanism of the viral particles by changing the pH has been extensively studied using the tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) [21]. An electron microscope study revealed that TMV particles were uniformly at pH 6.8, whereas low hydrogen-ion concentrations caused no aggregation but rather a breaking off the rod-shaped virus particles, reducing the homogeneity of TMV particles [22]. Importantly, the complete loss of both infectivity and antigenicity occurred at pH 12.4, destroying the structure of the virus rods and producing small globular deposits [22]. A similar study using a purified non-enveloped poliovirus reported that treatment of the virus particles at pH 10.0 freed the trace components rich in the VP4 capsid protein from the viral capsid and the remaining capsid structure showed the same H antigenicity as the intact, but empty, capsid without viral RNA. However, at pH 12.0, it decomposed into smaller components, which showed no H antigenicity [23]. These results indicate that the basic structure and antigenicity of viral particles are significantly impaired by the alkaline treatment. In our study, highly alkaline SAIW (pH 12.5) strongly inhibited the infectivity of all viruses tested (Fig. 1A and Table 1) and was shown to inactivate the binding of SARS-CoV-2 to target cells (Fig. 1C). Similarly, the growth of three Gram-negative bacteria was completely inhibited by treatment with SAIW (Table 2). Since viral and bacterial infection events are delicate and such biological activity is efficiently exerted near physiological pH, it is likely that the fatal biological change of the pathogen occurs before the protein components are denatured.

In conclusion, SAIW holds promise for an effective and safe disinfectant. Since SAIW is composed of water and a negligible amount of KOH, it does not produce chlorine or pungent odors, nor is it a substance that poses a risk or the need for first aid. In addition, SAIW should not be sensitive to geographical conditions since it can be easily made wherever there is electricity. SAIW is an environmentally friendly and sustainable disinfectant and meets the requirements for achieving the goals of SDGs, as it is diluted with water, and the pH becomes neutral and returns to natural water. Therefore, our future research will point toward the validation of whether SAIW can serve as a new disinfectant for future infectious disease control, especially if spraying in confined spaces is suitable for safe decontamination of air and environment.

Declaration of competing interest

Tamio Matsuzawa is an employee of E-PLAN Co. Ltd.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Ryusuke Matsuzawa for his insightful technical advice. This work was supported by Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under Grant Number JP19fk0108104.

References

- 1.Barker J., Stevens D., Bloomfield S.F. Spread and prevention of some common viral infections in community facilities and domestic homes. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2001;91:7–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01364.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker C.L.F., Rudan I., Liu L., Nair H., Theodoratou E., Bhutta Z.A., O'Brien K.L., Campbell H., Black R.E. Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea. Lancet. 2013;381:1405–1416. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60222-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boone S.A., Gerba C.P. Significance of fomites in the spread of respiratory and enteric viral disease. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:1687–1696. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02051-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petersen E., Koopmans M., Go U., Hamer D.H., Petrosillo N., Castelli F., Storgaard M., Khalili S.A., Simonsen L. Comparing SARS-CoV-2 with SARS-CoV and influenza pandemics. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:e238–e244. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30484-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu C., Chen X., Cai Y., Xia J., Zhou X., Xu S., Huang H., Zhang L., Zhou X., Du C., Zhang Y., Song J., Wang S., Chao Y., Yang Z., Xu J., Zhou X., Chen D., Xiong W., Xu L., Zhou F., Jiang J., Bai C., Zheng J., Song Y. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020;180:934–943. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colantuoni A., Martini R., Caprari P., Ballestri M., Capecchi P.L., Gnasso A., Presti R.L., Marcoccia A., Rossi M., Caimi G. COVID-19 Sepsis and microcirculation dysfunction. Front. Physiol. 2020;11:747. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.00747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogimi C., Kim Y.J., Martin E.T., Huh H.J., Chiu C.-H., Englund J.A. What's new with the old coronaviruses? J. Pediatric. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2020;9:210–217. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piaa037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garland S.M., Steben M. Genital herpes. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2014;28:1098–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2014.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howie R., Alfa M.J., Coombs K. Survival of enveloped and non-enveloped viruses on surfaces compared with other micro-organisms and impact of suboptimal disinfectant exposure. J. Hosp. Infect. 2008;69:368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2008.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bányai K., Estes M.K., Martella V., Parashar U.D. Viral gastroenteritis. Lancet. 2018;392:175–186. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31128-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holmes B., Costas M., Ganner M., On S.L., Stevens M. Evaluation of Biolog system for identification of some Gram-negative bacteria of clinical importance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1994;32:1970–1975. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.8.1970-1975.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rutala W.A., Weber D.J. Disinfection and sterilization in health care facilities: an overview and current issues. Infect. Dis. Clin. 2016;30:609–637. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shirato K., Nao N., Katano H., Takayama I., Saito S., Kato F., Katoh H., Sakata M., Nakatsu Y., Mori Y., Kageyama T., Matsuyama S., Takeda M. Development of genetic diagnostic methods for novel coronavirus 2019 (nCoV-2019) in Japan. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;73:304–307. doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2020.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamashita M., Tanaka J. Pulmonary collapse and pneumonia due to inhalation of a waterproofing aerosol in female CD-I Mice. J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 1995;33:631–637. doi: 10.3109/15563659509010620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wahlberg J.E., Lindberg M. In: Contact Dermatitis. fourth ed. Frosch P.J., Menne T., Lepoittevin J.P., editors. Springer; Germany: 2005. Patch testing; pp. 366–386. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khongwichit S., Sornjai W., Jitobaom K., Greenwood M., Greenwood M.P., Hitakarun A., Wikan N., Murphy D., Smith D.R. A functional interaction between GRP78 and Zika virus E protein. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:393. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-79803-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hricova D., Stean R., Zweifel C. Electrolyzed water and its application in the food industry. J. Food Protect. 2016;71:1934–1947. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-71.9.1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogunniyi A.D., Dandie C.E., Ferro S., Hall B., Drigo B., Brunetti G., Venter H., Myers B., Deo P., Donner E., Lombi E. Comparative antibacterial activities of neutral electrolyzed oxidizing water and other chlorine-based sanitizers. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:19955. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-56248-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moorman E., Montazeri N., Jaykus L. Efficacy of neutral electrolyzed water for inactivation of human norovirus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017;83:e00653. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00653-17. 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.N Bui V., Nguyen K.V., Pham N.T., Bui A.N., Dao T.D., Nguyen T.T., Nguyen H.T., Trinh D.Q., Inui K., Uchiumi H., Ogawa H., Imai K. Potential of electrolyzed water for disinfection of foot-and-mouth disease virus. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2017;79:16–614. doi: 10.1292/jvms.16-0614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perutz M. Electrostatic effects in proteins. Science. 1978;201:1187–1191. doi: 10.1126/science.694508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shikata E. Effects of different pH-values upon tobacco mosaic virus. Mem. Fac. Agric. Hokkaido. 1958;3:154–161. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katagiri S., Aikawa S., Hinuma Y. Stepwise degradation of poliovirus capsid by alkaline treatment. J. Gen. Virol. 1971;13:101–109. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-13-1-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]