ABSTRACT

Vaccine coverage is below desired levels in Canada, despite National Advisory Committee on Immunization recommendations. One solution to improve coverage is to offer vaccines in pharmacies. We explore the awareness, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of the general public in four communities in Nova Scotia (NS) and New Brunswick (NB) about the changing role of pharmacists as immunizers. Adult members of the public were invited to complete an online survey through advertisements in print and online, and through e-mail lists at local universities. Immunization status among participants (n = 985) varied across vaccines with slightly more than one-half of the participants (51.8%) reporting receipt of a seasonal influenza vaccine last year, 38.0% reporting receipt of the meningococcal C or ACWY vaccine, and 77.7% reporting receipt of the pertussis vaccine. Despite variable self-reported receipt of vaccines, the pervasive belief that participants were not at risk of getting vaccine-preventable diseases, and a lack of awareness about which vaccines are recommended for adults, participants in this study held vaccine-positive beliefs. Participants, especially those who had previously been vaccinated in a pharmacy (39.0%), were supportive of the inclusion of pharmacists as immunizers although nearly one-half of the participants would feel more comfortable getting vaccinated by a pharmacist if another practitioner recommended it to them. While cost threatens to be a barrier to pharmacists as immunizers, this study suggests that they are well-positioned to improve vaccine coverage and to communicate recommendations and other vaccine-related information to the public.

KEYWORDS: Immunization; vaccination; vaccination coverage; pharmacists; health, knowledge, attitudes; practice; public health

Introduction

The National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) in Canada recommends routine vaccination to protect adults from infectious diseases.1 NACI recommends that healthy adults without contraindications receive an annual influenza vaccine and that adults aged 65 and older receive the high-dose influenza vaccine.2 It also recommends that healthy adults receive one dose of the pertussis vaccine in adulthood, especially if they expect to be in close contact with infants.1 NACI recommends a vaccine against meningitis (either meningococcal serogroup B (MenB) or sero-group ACWY (MenACWY)) for healthy adults 24 years of age and younger if they never received it as a teenager.1 Despite these and other recommendations, vaccine uptake among healthy adults is markedly below recently updated national vaccination coverage goals.1,3–5 Barriers to achieving high vaccination coverage are multifactorial and most commonly include lack of information from healthcare providers about vaccines and the diseases that they prevent, misinformation about adult vaccine eligibility, uncertainty about vaccine schedules, lack of infrastructure to deliver vaccines, vaccine inaccessibility, financial constraints, and the attitudes of both the public and providers toward vaccination.6–8

Pharmacists are in a unique position of being among the most accessible and trusted of health professionals, exceeded only by family doctors, medical specialists, and nurses.9–11 Given their extended hours of operation, trustworthiness, and convenient locations, particularly for patients living in rural communities, pharmacists are well-positioned to improve vaccination rates and health system effectiveness by undertaking vaccine administration.12–14 Preliminary Canadian studies have shown a modest increase in vaccinations in provinces where pharmacists are authorized to immunize.15–17 Additionally, in the United States, pharmacists as immunizers have demonstrated an increase in vaccine uptake.18,19 As of 2020, nine Canadian provinces have legislation allowing pharmacists to provide immunizations to adults and, in some provinces, adolescents and children.20,21 Another province and territory promise to follow suit in the near future.22,23 Pharmacists in New Brunswick were authorized as immunizers in 2010, and by the 2013–2014 influenza season there were 330 pharmacists administering more than 40,000 influenza vaccines in the province.24 The 2013–2014 influenza season was the first year that pharmacists were authorized to administer vaccines in Nova Scotia. More than 78,000 influenza vaccines were administered by pharmacists that year, contributing to a 15.8% increase in the total number of influenza vaccines administered, compared to the previous influenza season when they were not yet regulated and funded to administer vaccinations.16

There have been limited studies detailing the impact of the expansion of the professional role of pharmacists as immunizers on the awareness, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of the general public and other immunization providers. This study aimed to expand our understanding of the awareness, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of the general public about pharmacists as immunizers. In preparation for an interventional study, baseline information was collected and is presented in this article. As such, all hypotheses are dependent on post-intervention data for comparison and will be presented and (dis)proven in a subsequent publication. This study took place in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia on the east coast of Canada (population densities of 10.5 and 17.4 per square kilometer, respectively).25

Methods

This study used a cross-sectional quantitative survey to assess the awareness, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of community-dwelling adult members of the public about pharmacists as immunizers. The survey opened on February 23, 2017 and was completed no later than November 1, 2017, allowing a 35-week window for completion and submission. The survey was left open longer than originally anticipated to improve the response rate, particularly among older adults.

Setting

This article details findings from a pre-implementation survey for an intervention aimed at improving vaccine coverage. The two intervention communities were geographically separated to minimize cross-contamination of patients receiving healthcare at different regional health centers. Based on our inclusion criteria, four communities were selected: two urban or suburban communities in New Brunswick (Saint John, Moncton, and surrounding areas) and two primarily rural communities in Nova Scotia (Kentville, New Glasgow, and surrounding areas).

Population and sample

All individuals ≥18 years of age in the four communities in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick were eligible to participate in the survey. Adult residents were informed about the survey and invited to participate by means of local advertisements in community print and online publications, posters, social media, e-mails to students, staff, and faculty mailing lists at local universities, and information distributed in community pharmacies. Advertisements contained the web address for the online survey.

Survey instrument

A validated questionnaire was developed using a formative process informed by the Theory of Planned Behavior with target constructs from the Health Belief Model.26–29 The survey instrument was constructed following the principles of survey design of Dillman, Smyth, and Christian.30 The questionnaire contained 86 yes or no or strength of agreement questions using a Likert scale measuring awareness of vaccine availability, attitudes toward vaccines, perceived social pressures to vaccinate, vaccine accessibility, intention to vaccinate, the use of pharmacists as immunizers, and willingness to pay for vaccines. Questions from questionnaires previously created by our investigator group were employed whenever possible.31–33

Reliability and validity

Prior to distributing the survey, the validity of individual questions and the questionnaire as a whole were evaluated by a panel of six experts comprised of nurses, pharmacists, and infectious disease physicians at the Canadian Center for Vaccinology (CCfV). The panel determined relevance using a rating worksheet. Each item was rated using a standard content validity index with a 4-point ordinal rating scale, where 1 indicated irrelevance and 4 high relevance. Items that received a score of 3 or 4 were judged to have content validity. Items that did not achieve the required minimum score were reviewed carefully by coauthors and reworded if and when appropriate. Some items were neither changed nor eliminated based on experts’ suggestions because of existing literature and theoretical underpinnings of the survey instrument (e.g., questions about cues-to-action such as how often respondents visit a physician, those about subjective norms such as whether or not they think their healthcare providers, friends and/or family think that it is important for them to be vaccinated). Two experts also suggested that the questions that parsed meningococcal serogroups and influenza vaccination dose levels would be too confusing for participants from the general public. Again, we opted to leave these questions in the survey as we felt that this uncertainty would be valuable to capture.

Test-retest reliability was assessed by having six members of the general public complete the questionnaires at two different points in time (approximately 14 days apart). A correlation co-efficient was calculated to compare the two sets of responses; questionnaire responses with a coefficient >0.70 were interpreted as consistent. We decided not to eliminate any questions based on test-retest reliability alone as the sample size was too small to be conclusive. We did, however, review any items that scored below the threshold and adjusted them when appropriate.

Statistical analysis

The first level of analysis comprised a review of the descriptive statistics for trends in the data. The second level of analysis involved tests of association between attitudinal, intentional, influential, behavioral, and belief-based outcomes and predictors. Differences in nominal survey responses were assessed using Fisher’s exact tests. For continuous predictor variables, logistic regression was used. Associations between attitudinal, behavioral, and demographic characteristics were either estimated using ordinal logistic regression or Fisher’s exact tests depending on whether or not the order of categories was of importance. Overall knowledge scores were compared using t-tests. Analysis was undertaken using Statistical Analysis Software (SAS®, version 9.4);34 p-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Predictive models were built based on behavioral change theories and existing literature and used demographic and population characteristic variables. Multiple logistic regression was done to predict binary knowledge responses, and ordinal logistic regression to predict ordered attitudinal responses. For each outcome variable, whether binary or ordered, demographic and population characteristic variables were used in a backwards elimination stepwise procedure to develop a multiple regression model. The predictors were selected based on vaccine literature and the behavior change theories cited above. Those predictor variables remaining at the end of the stepwise procedure were summarized and p-values calculated. P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

A minimum sample size of 400 individuals was selected to provide a 95% confidence interval (CI) of a maximum ±5% around the point estimate for any survey question.

Results

Demographics

A total of 985 responses were received, of which 76.8% were female. Participants aged 18 to 24 years made up the largest age demographic in the sample (37.0%); responses tapered in each age group thereafter, with 8.8% of participants aged 65 years and older. A considerable number of participants were Bachelor’s degree holders (31.3%) and high school graduates (27.5%). The most commonly reported annual household income bracket was <39,000 CAD (21.2%), followed closely by the 39,000 CAD to <70,000 CAD bracket (20.2%). The remainder of participants were spread relatively evenly across the higher income brackets (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

| Characteristic | n | % | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 224 | 22.7 | (19.7–26.1) |

| Female | 756 | 76.8 | (73.4–79.8) |

| Other | 5 | 0.5 | (0.2–1.4) |

| Age | |||

| 18 to 24 years of age | 364 | 37.0 | (33.0–41.1) |

| 25 to 34 years of age | 184 | 18.7 | (15.6–22.2) |

| 35 to 44 years of age | 145 | 14.7 | (12.0–17.9) |

| 45 to 54 years of age | 115 | 11.7 | (9.2–14.6) |

| 55 to 64 years of age | 90 | 9.1 | (7.0–11.9) |

| 65 + years of age | 87 | 8.8 | (6.7, 11.5) |

| Highest completed level of education | |||

| Elementary | 7 | 0.7 | (0.3, 1.9) |

| High school | 271 | 27.5 | (23.9–31.5) |

| College or pre-university | 156 | 15.8 | (13.0–19.2) |

| University certificate or diploma | 67 | 6.8 | (4.9–9.3) |

| Bachelor ‘s degree | 308 | 31.3 | (27.4–35.4) |

| Master’s degree | 107 | 10.9 | (8.5–13.8) |

| Doctorate degree | 69 | 7.0 | (5.1–9.5) |

| Annual household income | |||

| <$39,000 | 209 | 21.2 | (18.0–24.9) |

| $39,000 to <$70,000 | 199 | 20.2 | (17.0–23.8) |

| $70,000 to <$90,000 | 142 | 14.4 | (11.7–17.6) |

| $90,000 to <$125,000 | 137 | 13.9 | (11.3–17.1) |

| ≥$125,000 | 150 | 15.2 | (12.5–18.5) |

| I prefer not to answer | 148 | 15 | (12.3–18.3) |

Vaccination behavior

Immunization status was variable across vaccines: slightly more than one-half of the participants (51.8%) reported receiving a seasonal influenza vaccine in the previous year, and 38.0% reported ever receiving the meningococcal C (MenC) or MenACWY vaccine, and 77.7% reported ever receiving the pertussis vaccine. Of those participants eligible to receive a high-dose influenza vaccine (65 years of age or older), 4.6% reported ever receiving one. Meningococcal B vaccination was reported by 44.0% of participants aged 18 to 24 years old. Slightly more than one-half of the participants (50.9%) believed themselves to have received all vaccines recommended for adults, while 31.5% did not know whether they had or not (Table 2).

Table 2.

Vaccination behavior

| Characteristic | n | % | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Received seasonal influenza vaccine last year | |||

| Yes | 510 | 51.8 | (48.0–55.6) |

| No | 463 | 47.0 | (43.2–50.8) |

| I don’t know | 12 | 1.2 | (0.6–2.4) |

| Ever received Men C or ACWY vaccine | |||

| Yes | 374 | 38.0 | (34.3–41.7) |

| No | 301 | 30.6 | (27.2–34.2) |

| I don’t know | 310 | 31.5 | (28.0–35.1) |

| Ever received Tdap vaccine | |||

| Yes | 765 | 77.7 | (74.3–80.7) |

| No | 87 | 8.8 | (6.9–11.2) |

| I don’t know | 133 | 13.5 | (11.1–16.3) |

| Ever received high-dose influenza vaccinea | |||

| Yes | 4 | 4.6 | (1.5–13.3) |

| No | 52 | 59.8 | (47.0–71.4) |

| I don’t know | 31 | 35.6 | (24.6–48.5) |

| Ever received Men B vaccineb | |||

| Yes | 160 | 44.0 | (37.9–50.2) |

| No | 40 | 11.0 | (7.7–15.5) |

| I don’t know | 164 | 45.1 | (38.9–51.3) |

| Received all vaccines recommended for adults | |||

| Yes | 501 | 50.9 | (47.1–54.7) |

| No | 174 | 17.7 | (14.9–20.8) |

| I don’t know | 310 | 31.5 | (28.0–35.1) |

aThis was a contingency question for participants aged 65 Years and older (n = 87).

bThis was a contingency question for participants between 18 and 24 years old (n = 364).

Attitudes, beliefs, and awareness about vaccination

Participants in this study generally held vaccine-positive attitudes and beliefs, the most common among them being that vaccines protect the people they care about from getting sick (87.5%). Participants also tended to agree that vaccination is important to them (86.9%), that it is their moral responsibility to be vaccinated (78.4%), and that they trust the current scientific knowledge (85.5%) and recommendations made by public health (84.9%) about vaccines. From a more logistical standpoint, the majority of participants (81.9%) reported vaccines to be easily accessible to them. Most participants (72.3%) reported having enough information to decide whether or not to get vaccinated, but 19.0% were uncertain about whether or not they ought to be vaccinated.

Participants agreed that influenza (71.0%) and meningitis (61.4%) pose a serious threat to the health of adults. They were less convinced that they personally were at risk of developing influenza (34.2%), meningitis (11.3%), and pertussis (15.1%). Less than 10% of participants believed influenza, meningitis, and pertussis to be rare enough that they no longer need to be vaccinated with those antigens.

Except for the influenza vaccine, participants were more likely to be unaware than aware of the NACI recommendations for vaccination against meningitis (ACWY and B), pertussis, and the high-dose influenza vaccine (Table 3).

Table 3.

Attitudes, beliefs, and awareness about vaccination

| Characteristic | n | % | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccination is important to me | ||||

| Disagree | 81 | 8.2 | (6.4–10.6) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 48 | 4.9 | (3.5–6.8) | |

| Agree | 856 | 86.9 | (84.1–89.3) | |

| Receiving vaccines protects the people I care about from getting ill | ||||

| Disagree | 72 | 7.3 | (5.6–9.6) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 51 | 5.2 | (3.7–7.1) | |

| Agree | 862 | 87.5 | (84.8–89.8) | |

| I am uncertain about whether I should be vaccinated | ||||

| Disagree | 690 | 70.1 | (66.4–73.4) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 108 | 11 | (8.8–13.6) | |

| Agree | 187 | 19.0 | (16.2–22.2) | |

| I have enough information to decide whether to get vaccinated | ||||

| Disagree | 170 | 17.3 | (14.6–20.3) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 103 | 10.5 | (8.3–13.0) | |

| Agree | 712 | 72.3 | (68.7–75.6) | |

| I feel that it is my moral responsibility to be vaccinated | ||||

| Disagree | 122 | 12.4 | (10.1–15.1) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 91 | 9.2 | (7.3–11.7) | |

| Agree | 772 | 78.4 | (75.1–81.3) | |

| Convenience is a factor in deciding to get vaccinated | ||||

| Disagree | 520 | 52.8 | (49.0–56.6) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 105 | 10.7 | (8.5–13.2) | |

| Agree | 360 | 36.5 | (33.0–40.3) | |

| Vaccines are easily accessible to me | ||||

| Disagree | 60 | 6.1 | (4.5–8.2) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 118 | 12.0 | (9.7–14.7) | |

| Agree | 807 | 81.9 | (78.8–84.7) | |

| I don’t have time to get vaccinated | ||||

| Disagree | 776 | 78.8 | (75.5–81.7) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 123 | 12.5 | (10.2–15.2) | |

| Agree | 86 | 8.7 | (6.8–11.1) | |

| I trust current scientific knowledge about vaccines | ||||

| Disagree | 78 | 7.9 | (6.1–10.2) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 65 | 6.6 | (4.9–8.8) | |

| Agree | 842 | 85.5 | (82.6–88.0) | |

| I trust vaccine recommendations made by public health officials in Canada | ||||

| Disagree | 94 | 9.5 | (7.5–12.0) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 55 | 5.6 | (4.1–7.6) | |

| Agree | 836 | 84.9 | (81.9–87.4) | |

| Influenza poses a serious threat to the health of adults | ||||

| Disagree | 158 | 16.0 | (13.4–19.0) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 128 | 13.0 | (10.6–15.8) | |

| Agree | 699 | 71.0 | (67.4–74.3) | |

| I am at a significant risk of developing influenza | ||||

| Disagree | 396 | 40.2 | (36.5–44.0) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 252 | 25.6 | (22.4–29.0) | |

| Agree | 337 | 34.2 | (30.7–37.9) | |

| Influenza is rare enough that I no longer need to be vaccinated against it | ||||

| Disagree | 700 | 71.1 | (67.5–74.4) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 215 | 21.8 | (18.8–25.1) | |

| Agree | 70 | 7.1 | (5.4–9.3) | |

| Meningitis poses a serious threat to the health of adults | ||||

| Disagree | 89 | 9.0 | (7.1–11.5) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 291 | 29.5 | (26.2–33.1) | |

| Agree | 605 | 61.4 | (57.7–65.1) | |

| I am at a significant risk of developing meningitis | ||||

| Disagree | 396 | 40.2 | (36.5–44.0) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 478 | 48.5 | (44.7–52.3) | |

| Agree | 111 | 11.3 | (9.1–13.9) | |

| Meningitis is rare enough that I no longer need to be vaccinated against it | ||||

| Disagree | 513 | 52.1 | (48.3–55.9) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 386 | 39.2 | (35.5–43.0) | |

| Agree | 86 | 8.7 | (6.8–11.1) | |

| I am at a significant risk of developing pertussis | ||||

| Disagree | 467 | 47.4 | (43.6–51.2) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 369 | 37.5 | (33.9–41.2) | |

| Agree | 149 | 15.1 | (12.6–18.1) | |

| Pertussis is rare enough that I no longer need to be vaccinated against it | ||||

| Disagree | 555 | 56.3 | (52.5–60.1) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 332 | 33.7 | (30.2–37.4) | |

| Agree | 98 | 9.9 | (7.9–12.5) | |

| My healthcare provider thinks it is important for me to be vaccinated | ||||

| Disagree | 40 | 4.1 | (2.8–5.9) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 239 | 24.3 | (21.1–27.7) | |

| Agree | 706 | 71.7 | (68.1–75.0) | |

| My friends and family think it is important for me to be vaccinated | ||||

| Disagree | 115 | 11.7 | (9.4–14.3) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 218 | 22.1 | (19.1–25.5) | |

| Agree | 652 | 66.2 | (62.5–69.7) | |

| I feel under social pressure to receive vaccines | ||||

| Disagree | 458 | 46.5 | (42.7–50.3) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 243 | 24.7 | (21.5–28.1) | |

| Agree | 284 | 28.8 | (25.5–32.4) | |

| I have enough support and advice to make a choice about vaccines | ||||

| Disagree | 102 | 10.4 | (8.3–12.9) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 104 | 10.6 | (8.4–13.1) | |

| Agree | 779 | 79.1 | (75.8–82.0) | |

| I agree with which vaccines are currently provided free of charge | ||||

| Disagree | 107 | 10.9 | (8.7–13.5) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 237 | 24.1 | (21.0–27.5) | |

| Agree | 641 | 65.1 | (61.4–68.6) | |

| NACI recommendation for annual influenza vaccine | ||||

| Aware | 770 | 78.2 | (75.1–81.0) | |

| NACI recommendation for meningococcal ACWY vaccine | ||||

| Aware | 463 | 47.0 | (43.5–50.6) | |

| NACI recommendation for pertussis vaccine | ||||

| Aware | 432 | 43.9 | (40.4–47.4) | |

| NACI recommendation for high-dose influenza vaccine | ||||

| Aware | 28 | 2.8 | (1.8–4.4) | |

| NACI recommendation for meningococcal B vaccine | ||||

| Aware | 178 | 18.1 | (15.3–21.2) | |

Factors associated with being vaccinated

A multitude of independent awareness, attitudinal, behavioral, and belief-based variables were predictive of self-reported receipt of the seasonal influenza, meningococcal, and pertussis vaccines in the univariable analyses (for the direction and magnitude of effect, please refer to Supplementary Table 1). For the seasonal influenza vaccine, multivariable analyses revealed the following to increase odds of influenza vaccination among participants: older age, access to a family physician, previous receipt of a vaccination by a pharmacist, having ever been offered an influenza vaccine, self-reported receipt of all recommended vaccines, and awareness of and agreement with the NACI recommendation for annual influenza vaccination. Those participants who received their vaccine-related information from the media had lower odds of having received the influenza vaccine than those participants who did not identify the media as a source of information. Multivariable analyses revealed increased odds of having received the MenC or MenACWY vaccine among participants who self-reported receipt of all vaccines recommended for adults, who had been offered a MenACWY vaccine, who were aware of the NACI recommendation for receipt of MenACWY to protect healthy adolescents from meningitis, and who trusted public health recommendations. Participants 45 years of age and older were less likely to have received a meningococcal vaccine, but the recommendation is for healthy adolescents and adults (aged 12 to 24 years old). Participants who reported receiving all the vaccines recommended for adults, who had been offered the Tdap vaccine, to whom vaccination is important, and who trust current scientific knowledge were more likely to have received a Tdap vaccine. Participants 25 to 54 years of age had higher odds of having received a Tdap vaccine compared to those aged 18 to 24 years. Adults 65 years of age and older had the lowest odds of having received the Tdap vaccine. Among those participants eligible for the MenB vaccine, having been offered a MenB vaccine and awareness of the NACI recommendation for receipt of MenB were predictive of receipt of the MenB vaccine (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors associated with being vaccinated

| Seasonal Influenza Vaccine |

Meningitis C or ACWY Vaccine |

Tdap Vaccine |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Synopsis of Statements | Univariable/Multivariable p-value | Univariable/Multivariable p-value | Univariable/Multivariable p-value |

| 2. How old are you? | <0.001/<0.001 | <0.001/<0.001 | <0.001/0.003 |

| 4. What is the highest level of education you have completed? | 0.011/NA | <0.001/NA | 0.014/NA |

| 5. What is the annual income of your household? | 0.02/NA | 0.048/NA | |

| 11. Have you received all of the vaccines that are recommended for adults? | <0.001/0.001 | <0.001/0.002 | <0.001/0.02 |

| 13. Do you have a family physician? | <0.001/0.031 | ||

| 14. On average, how often do you visit a physician? | <0.001/NA | ||

| 15. On average how often do you visit a pharmacy? | <0.001/NA | <0.001/NA | |

| 16. Are you aware that many pharmacists are trained to administer vaccines? | <0.001/NA | ||

| 17. Which of the following vaccines are currently administered by pharmacists? | |||

| Influenza | <0.001/NA | <0.001/0.011 | |

| Tdap | 0.041/NA | ||

| Men B | 0.032/NA | ||

| I don’t know | <0.001/NA | <0.001/NA | |

| 18. Have you ever received a vaccination by a pharmacist in a pharmacy? | <0.001/<0.001 | 0.002/NA | |

| 19. Have your healthcare providers informed you of vaccines you should receive? | <0.001/NA | 0.003/NA | |

| 20. Have you ever been offered an influenza vaccine? | <0.001/0.026 | ||

| 21. Have you ever been offered a meningococcal ACWY vaccine? | <0.001/<0.001 | ||

| 22. Have you ever been offered a Tdap vaccine? | <0.001/<0.001 | ||

| 25. Vaccination is important to me | <0.001/NA | <0.001/NA | <0.001/0.006 |

| 26. Receiving vaccines protects the people I care about from getting ill | <0.001/NA | <0.001/NA | <0.001/NA |

| 27. I am uncertain about whether I should be vaccinated | <0.001/NA | 0.01/NA | 0.006/NA |

| 28. I have enough information to decide whether or not to get vaccinated | <0.001/NA | 0.002/NA | 0.008/NA |

| 29. I feel that it is my moral responsibility to be vaccinated | <0.001/NA | <0.001/NA | <0.001/NA |

| 30. Convenience is a factor in deciding whether or not to get vaccinated | 0.009/NA | 0.036/NA | |

| 31. Vaccines are easily accessible to me | <0.001/NA | 0.027/NA | |

| 32. I don’t have time to get vaccinated | <0.001/0.042 | ||

| 39. Influenza poses a serious threat to the health of adults | <0.001/NA | ||

| 40. I am at a significant risk for developing influenza | <0.001/NA | ||

| 41. Influenza is rare enough that I no longer need to be vaccinated against it | <0.001/<0.001 | ||

| 42. Meningitis poses a serious threat to the health of adults | <0.001/NA | ||

| 43. I am at a significant risk for developing meningitis | <0.001/NA | ||

| 44. Meningitis is rare enough that I no longer need to be vaccinated against it | <0.001/NA | ||

| 46. Pertussis is rare enough that I no longer need to be vaccinated against it | <0.001/NA | ||

| 67. My healthcare provider thinks it is important for me to receive vaccines | <0.001/NA | <0.001/NA | 0.002/NA |

| 68. My friends and family think that it is important for me to receive vaccines | <0.001/NA | <0.001/NA | <0.001/NA |

| 70. I have enough support and advice to make a choice about vaccines | <0.001/NA | <0.001/NA | 0.004/0.028 |

| 71. Where do you get your information about vaccination? | |||

| Family physician | <0.001 | <0.001/NA | 0.001/NA |

| Nurse | 0.018 | <0.001/NA | |

| Pharmacist | <0.001 | 0.028/NA | |

| Media | 0.002/0.021 | 0.002/NA | |

| Internet | <0.001 | ||

| Other | 0.007/NA | ||

| 72. Are you aware that the NACI recommends that adults get an annual influenza vaccine? | <0.001/<0.001 | ||

| 72.1 Do you agree with the NACI recommendation? | <0.001/<0.001 | ||

| 73. Are you aware that the NACI recommends that adolescents/young adults get a Men ACWY vaccine? | <0.001/0.011 | ||

| 73.1 Do you agree with the NACI recommendation? | <0.001/NA | ||

| 74.1 Do you agree with the NACI [Tdap] recommendation? | <0.001/NA | ||

| 77. I trust current scientific knowledge about vaccines | <0.001/NA | <0.001/NA | <0.001/0.005 |

| 78. I trust vaccine recommendations made by public health officials | <0.001/NA | <0.001/<0.001 | <0.001/NA |

| 79. The current Canadian vaccine guidelines are promoted adequately | <0.001/NA | <0.001/NA | 0.001/NA |

| 81. Do you know which vaccines you should receive based on public health recommendations? | 0.008/NA | 0.02/NA |

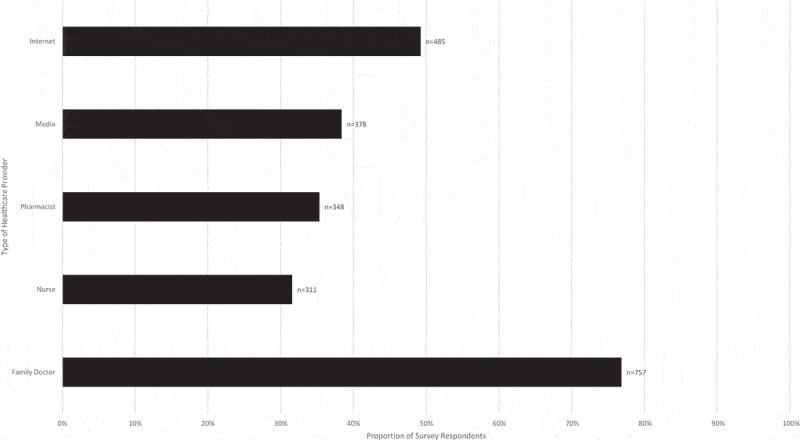

Sources of vaccine-related information

The most frequently identified source of vaccine-related information among participants was their family doctor (76.9%) followed by the internet (49.2%), media (38.4%), their pharmacist (35.3%), and finally their nurse (31.6%). Most participants reported that their healthcare providers (71.7%) and their friends and families (66.2%) think it is important for them to be vaccinated, and more than one-quarter of the participants (28.8%) felt they were under social pressure to be vaccinated. The predominant sentiment among participants was that they had enough support and advice to make choices about vaccines (79.1%) (Table 3 and Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sources of vaccine-related information. Bars indicate the number and proportion of respondents who identified each source of vaccine-related information in response to a select-all-that-apply question

Sources of influence

There was an array of independent variables associated with participants’ identified sources of vaccine-related information in the univariable analysis (for the direction and magnitude of effect, please refer to Supplementary Table 2). Multivariable analyses revealed family physicians to be a source of vaccine-related information among those participants who visit a physician frequently (a minimum of two times per year or more). Participants had higher odds of identifying nurses as a source of vaccine-related information if they were between the ages of 18 and 24 years. Pharmacists were a source of vaccine-related information among participants who reported visiting a pharmacy 7 or more times annually. Participants aged 35 years and older and for whom convenience is a factor in deciding whether or not to be vaccinated had the highest odds of getting their vaccine-related information from the media. The internet was identified as a source of vaccine-related information by participants aged 34 years and younger, those who felt that it was not their moral responsibility to be vaccinated, and among those who did not feel at significant risk of developing influenza (Table 5).

Table 5.

Factors associated with sources of information

| Family Physician |

Nurse |

Pharmacist |

Media |

Internet |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synopsis of Statements | Univariable/Multivariable p-value | Univariable/Multivariable p-value | Univariable/Multivariable p-value | Univariable/Multivariable p-value | Univariable/Multivariable p-value |

| 2. How old are you? | <0.001/<0.001 | 0.012/0.008 | <0.001/<0.001 | ||

| 4. What is the highest level of education you have completed? | 0.023 | ||||

| 6. Did you receive a seasonal influenza vaccine last year? | <0.001 | <0.001/0.012 | 0.001/0.004 | <0.001/0.003 | |

| 7. Have you ever received the meningococcal C or meningococcal ACWY vaccine? | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.048 | 0.001 | |

| 8. Have you ever received a vaccine to protect you from whooping cough/pertussis (Tdap)? | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.018 | ||

| 11. Have you received all of the vaccines that are recommended for adults? | <0.001 | 0.004 | <0.001/0.040 | <0.001 | 0.017 |

| 13. Do you have a family physician? | <0.001/<0.001 | 0.019 | |||

| 14. On average, how often do you visit a physician? | <0.001/<0.001 | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.021 | |

| 15. On average how often do you visit a pharmacy? | <0.001 | <0.001/<0.001 | |||

| 20. Have you ever been offered an influenza vaccine? | <0.001/0.003 | 0.048 | <0.001 | ||

| 21. Have you ever been offered a meningococcal ACWY vaccine? | <0.001/0.005 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.017 | |

| 22. Have you ever been offered a Tdap vaccine? | <0.001 | <0.001/<0.001 | <0.001/0.011 | 0.002 | |

| 25. Vaccination is important to me | <0.001 | 0.037 | <0.001 | 0.029 | 0.009 |

| 26. Receiving vaccines protects the people I care about from getting ill | <0.001 | 0.005 | 0.002 | ||

| 27. I am uncertain about whether I should be vaccinated | 0.036 | 0.006 | 0.035 | ||

| 28. I have enough information to decide whether or not to get vaccinated | <0.001/0.018 | <0.001 | 0.003 | ||

| 29. I feel that it is my moral responsibility to be vaccinated | <0.001 | 0.006 | <0.001 | 0.041 | <0.001/0.011 |

| 30. Convenience is a factor in deciding whether or not to get vaccinated | 0.005/<0.001 | ||||

| 31. Vaccines are easily accessible to me | <0.001 | 0.021 | <0.001 | ||

| 32. I don’t have time to get vaccinated | <0.001 | 0.013 | |||

| 39. Influenza poses a serious threat to the health of adults | <0.001/<0.001 | 0.036 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| 40. I am at a significant risk for developing influenza | 0.004 | <0.001 | 0.01/0.005 | ||

| 41. Influenza is rare enough that I no longer need to be vaccinated against it | <0.001 | 0.045 | |||

| 42. Meningitis poses a serious threat to the health of adults | <0.001 | 0.013 | 0.003 | <0.001 | |

| 43. I am at a significant risk for developing meningitis | 0.008/0.002 | 0.006/0.004 | |||

| 44. Meningitis is rare enough that I no longer need to be vaccinated against it | 0.027 | <0.001 | 0.018 | 0.011 | 0.047 |

| 45. I am at a significant risk for developing pertussis | 0.003 | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.002 | |

| 46. Pertussis is rare enough that I no longer need to be vaccinated against it | <0.001 | 0.024 | |||

| 52. I would get a vaccine against influenza if it was recommended by a doctor | <0.001 | <0.001/0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| 53. I would get a vaccine against influenza if it was recommended by a nurse | <0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| 54. I would get a vaccine against influenza if it was recommended by a pharmacist | <0.001 | 0.007 | <0.001/0.015 | 0.010 | |

| 55. I would get a vaccine against MenACWY if it was recommended by a doctor | <0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 | ||

| 56. I would get a vaccine against MenACWY if it was recommended by a nurse | 0.003 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| 57. I would get a vaccine against MenACWY if it was recommended by a pharmacist | 0.005 | 0.022 | <0.001 | 0.046 | |

| 58. I would get a vaccine against pertussis if it was recommended by a doctor | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001/0.006 | ||

| 59. I would get a vaccine against pertussis if it was recommended by a nurse | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| 60. I would get a vaccine against pertussis if it was recommended by a pharmacist | 0.002 | 0.006 | <0.001/0.013 | 0.040 | |

| 72. Are you aware that the NACI recommends that adults get an annual influenza vaccine? | <0.001 | 0.049/0.017 | 0.001/0.048 | ||

| 72.1 Do you agree with the NACI recommendation? | <0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| 73. Are you aware that the NACI recommends that adolescents/young adults get a Men ACWY vaccine? | 0.030 | 0.029 | |||

| 73.1 Do you agree with the NACI [Men ACWY] recommendation? | <0.001 | 0.050 | <0.001/0.018 | <0.001 | |

| 74.1 Do you agree with the NACI [Tdap] recommendation? | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.006 |

| 77. I trust current scientific knowledge about vaccines | <0.001 | 0.023 | <0.001 | 0.022 | |

| 78. I trust vaccine recommendations made by public health officials | <0.001 | 0.029 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Attitudes and beliefs about pharmacists as immunizers

Most (87.2%) participants reported visiting their pharmacy more than once annually, with nearly one-half (46.4%) visiting 2 to 6 times annually. The majority of participants (86.3%) reported being aware that pharmacists are trained to vaccinate; however, 36.9% did not know which vaccines pharmacists were able to administer. Among those who reportedly did know, 73.5% were aware of pharmacists’ ability to give the influenza vaccine, 16.9% to give the Tdap vaccine, and only 11.5% to give the MenACWY and B vaccines. Participants were generally in agreement that pharmacists have enough training to vaccinate (76.8%), that they were comfortable getting vaccinated by a pharmacist (75.0%), and that it was convenient for them to get vaccinated by their pharmacist (70.7%). Despite being generally in favor of pharmacists as immunizers, less than one-half of the participants (39.0%) reported having been previously vaccinated by a pharmacist. Participants also reported that they would feel more comfortable getting vaccinated by a pharmacist if either their doctor (46.5%) or their nurse (39.1%) recommended it (Table 6).

Table 6.

Awareness, attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs about pharmacists as immunizers

| Characteristic | n | % | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of visits to the pharmacy | |||

| Less than once annually | 126 | 12.8 | (10.4–15.7) |

| 2 to 6 times annually | 457 | 46.4 | (42.5–50.4) |

| 7 to 12 times annually | 292 | 29.6 | (26.1–33.4) |

| More than once monthly | 110 | 11.2 | (8.9–13.9) |

| Aware that pharmacists are trained to vaccinate | |||

| Yes | 850 | 86.3 | (83.7–88.6) |

| Awareness of pharmacists’ ability to administer | |||

| Influenza vaccine | 724 | 73.5 | (70.6–76.2) |

| Tdap vaccine | 166 | 16.9 | (14.6–19.3) |

| Men ACWY vaccine | 113 | 11.5 | (9.5–13.6) |

| Men B vaccine | 113 | 11.5 | (9.5–13.6) |

| I don’t know | 363 | 36.9 | (33.8–40.0) |

| Previous vaccination by a pharmacist in a pharmacy | |||

| Yes | 384 | 39.0 | (35.6–42.5) |

| No | 601 | 61.0 | (57.5–64.4) |

| I feel comfortable getting vaccinated by a pharmacist | |||

| Disagree | 132 | 13.4 | (11.0–16.2) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 114 | 11.6 | (9.4–14.2) |

| Agree | 739 | 75.0 | (71.6–78.2) |

| It is convenient for me to get vaccinated by my pharmacist | |||

| Disagree | 88 | 8.9 | (7.0–11.4) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 201 | 20.4 | (17.5–23.6) |

| Agree | 696 | 70.7 | (67.1–74.0) |

| I think pharmacists have enough training to vaccinate | |||

| Disagree | 84 | 8.5 | (6.6–10.9) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 145 | 14.7 | (12.2–17.6) |

| Agree | 756 | 76.8 | (73.4–79.8) |

| I would feel more comfortable getting vaccinated by a pharmacist if my doctor recommended it | |||

| Disagree | 233 | 23.7 | (20.6–27.0) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 294 | 29.8 | (26.5–33.4) |

| Agree | 458 | 46.5 | (42.7–50.3) |

| I would feel more comfortable getting vaccinated by a pharmacist if a public health nurse recommended it | |||

| Disagree | 260 | 26.4 | (23.2–29.9) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 340 | 34.5 | (31.0–38.2) |

| Agree | 385 | 39.1 | (35.4–42.9) |

Factors associated with perceptions of pharmacists as immunizers

A multitude of independent variables were predictive of positive attitudes and beliefs about pharmacists as immunizers in the univariable analyses (for the direction and magnitude of effect, please refer to Supplementary Table 3). More frequent visits to the pharmacy (7 times per year or more) and previous vaccination by a pharmacist were both predictive of feeling comfortable getting vaccinated by a pharmacist. Participants who would get a vaccine against influenza or pertussis if it was recommended by a pharmacist also had higher odds of feeling comfortable getting vaccinated by a pharmacist than those who would not. Females had lower odds of feeling comfortable receiving vaccines from a pharmacist than their male counterparts.

Frequency of visits to the pharmacy was associated with the belief that pharmacists have enough training to give vaccines and followed something of a dose-response relationship with odds decreasing with fewer visits. Those participants who received their vaccine-related information from their pharmacists had higher odds of thinking that pharmacists have enough training to give vaccines compared to those who did not receive their information from pharmacists. Once again, females had lower odds of thinking that pharmacists have enough training to vaccinate than their male counterparts.

Frequency of visits to the pharmacy and previous receipt of a vaccine by a pharmacist were associated with the belief that it is convenient to get vaccinated at the pharmacy. Those participants who received their vaccine-related information from their pharmacist had higher odds of reporting that it was convenient for them to be vaccinated in a pharmacy than those that did not (Table 7).

Table 7.

Factors associated with awareness, attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs about pharmacists

| Comfort with Pharmacists as Immunizers |

Pharmacists Have Enough Training to Vaccinate |

Convenience of Pharmacists as Immunizers |

I would feel more comfortable receiving my vaccines in a pharmacy if my physician recommended it |

I would feel more comfortable receiving my vaccines in a pharmacy if a public health nurse recommended it |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synopsis of Statements | Univariable/Multivariable p-value | Univariable/Multivariable p-value | Univariable/Multivariable p-value | Univariable/Multivariable p-value | Univariable/Multivariable p-value |

| 1. What is your gender? | 0.017/0.005 | 0.026/0.004 | |||

| 2. How old are you? | 0.007 | 0.010 | <0.001 | <0.001/0.037 | |

| 4. What is the highest level of education you have completed? | <0.001/<0.001 | <0.001/0.030 | |||

| 5. What is the annual income of your household? | 0.016/0.016 | 0.046/0.031 | |||

| 13. Do you have a family physician? | 0.007/0.003 | ||||

| 14. On average, how often do you visit a physician? | 0.001 | 0.015/0.027 | 0.003 | ||

| 15. On average how often do you visit a pharmacy? | <0.001/0.007 | <0.001 | <0.001/0.006 | ||

| 16. Are you aware that many pharmacists are trained to administer vaccines? | <0.001 | <0.001/0.028 | 0.006 | <0.001/<0.001 | <0.001/<0.001 |

| 17. Which of the following vaccines are currently administered by pharmacists? | |||||

| Influenza | 0.031 | <0.001 | 0.002 | ||

| Tdap | 0.002/0.034 | 0.017 | |||

| Men ACWY | 0.019 | 0.041 | |||

| Men B | 0.023 | 0.017 | |||

| I don’t know | 0.026 | 0.004 | |||

| 18. Have you ever received a vaccination by a pharmacist in a pharmacy? | <0.001/<0.001 | <0.001/<0.001 | <0.001/<0.001 | 0.003/0.004 | 0.028/<0.001 |

| 54. I would get a vaccine against influenza if it was recommended by a pharmacist | <0.001/<0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001/<0.001 | <0.001/<0.001 |

| 57. I would get a vaccine against MenACWY if it was recommended by a pharmacist | <0.001 | <0.001/<0.001 | <0.001/<0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 60. I would get a vaccine against pertussis if it was recommended by a pharmacist | <0.001/<0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 71. Where do you get your information about vaccination? | |||||

| Family physician | <0.001 | 0.010 | 0.022/0.009 | ||

| Nurse | 0.009 | ||||

| Pharmacist | <0.001 | <0.001/0.042 | <0.001/0.002 | 0.017/0.002 | |

| Media | |||||

| Internet | 0.029 | ||||

| Other | <0.001 | <0.001/0.013 | <0.001 |

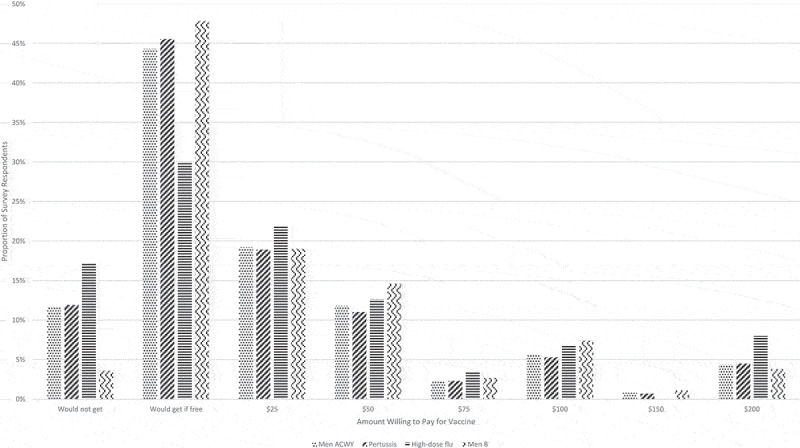

Attitudes toward paying for vaccines

Participants were asked to identify the most that they would be willing to pay out of pocket to receive vaccines and were provided a range of responses including “would not get”, “would get if provided free of charge,” “$25”, “$50”, “$75”, “$100”, “$150”, and “$200”. As depicted in Figure 2, the highest frequency of participants were willing to receive the MenACWY (44.3%), MenB (47.8%), and pertussis (45.5%) vaccines if they were provided free of charge. Fewer (29.9%) of those eligible for the high-dose influenza vaccine (aged 65 years and older) would receive it if it was provided for free. Thereafter, willingness to pay for all four of the vaccines decreased as the maximum price increased, with the fewest number of participants willing to pay 150 CAD for the MenACWY (0.8%), pertussis (0.7%), high-dose influenza (0%), and MenB (1.1%) vaccines. While most participants were either willing to get vaccines free of charge or pay for them, there was a minority who would not get the MenACWY (11.6%), pertussis (11.9%), high-dose influenza (17.2%, among those participants aged 65 and older, n = 87), and MenB (3.6%, among those participants aged 18 to 24 years old, n = 364) vaccines even if they were free of charge.

Figure 2.

Willingness to pay for vaccines. Bars indicate the number and proportion of respondents willing to get vaccinated with the meningococcal (ACWY and B), pertussis, and high-dose influenza vaccines depending on the price

Discussion

Since legislation was passed to allow pharmacists to provide immunizations, Canadian pharmacists’ primary immunization role has been in administering influenza vaccines. Literature detailing the impact of the expansion of the role of pharmacists to include the complete range of adult immunizations in Canada has been sparse.16 The primary objective of this study was to provide quantitative results detailing the awareness, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of the general public about the provision of several immunizations by pharmacists.

Despite variable self-reported receipt of vaccines recommended for adults, the pervasive belief that participants were not at risk of getting vaccine-preventable diseases, and a general lack of awareness about which vaccines are recommended for adults, participants in this study held vaccine-positive beliefs. Participants, especially those who had previously been vaccinated in a pharmacy, were supportive of the inclusion of pharmacists as immunizers even though nearly one-half of the participants would feel more comfortable being vaccinated by a pharmacist if another practitioner recommended it to them. Finally, costs threaten to be a barrier to pharmacists as immunizers, with less than one-quarter of the participants willing to be vaccinated if it were to cost them 25 CAD or more.

Awareness, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors about vaccination

Participants’ self-reported receipt of vaccines recommended for adults varied depending on the antigen in question; however, slightly more than half of them believed themselves to have received all of the vaccines recommended for adults. While attitudes and beliefs held by participants were generally vaccine-positive, participants believed their personal risk of getting vaccine-preventable diseases was low, and there was a lack of awareness of which vaccines are recommended for adults. Having been offered vaccines against influenza, meningitis, and pertussis was predictive of receipt of all three.

Recent results from the adult National Immunization Coverage Survey (aNICS) in Canada showed that 39.6% of respondents aged 18 years and older received the influenza vaccine.3 Self-reported receipt of the influenza vaccine in our study exceeds that of the aNICS, with 51.8% of participants reporting receipt of a seasonal influenza vaccine in the past year. Validation studies have found self-reported receipt of last season’s influenza vaccine to have high sensitivity (96.6%), specificity (88.2%), and positive predictive value (92.9%).35 Given these statistics as well as the annual nature and high profile of the influenza immunization campaign specifically, we believe our findings pertaining to influenza vaccine uptake to be internally valid.

Unfortunately the aNICS does not provide an estimate of meningococcal vaccine coverage; however, survey results from a study of students, faculty, and staff during a MenB outbreak found a general misunderstanding of the different meningococcal serogroups.36 Congruent with the findings of MacDougall and colleagues,36 participants in this study were especially uncertain about whether or not they had received the MenC or ACWY (31.5%) or the MenB (45.1%) vaccines. Importantly, the MenC or ACWY vaccines are given in school-based programs, while the MenB vaccine is not publicly funded in Canada. It is possible that those participants who believed themselves to have received the MenB vaccine in this study (44.0%) may actually have received the MenC or ACWY vaccine.

The aNICS estimates pertussis vaccine coverage to be 9.7% among adults aged 18 years and older.3 The self-reported coverage of the pertussis vaccine in this study was strikingly high at 77.7% in comparison. It is suspected that these results are spurious and that participants mistakenly reported that they had been immunized with the pertussis vaccine in adulthood, when in fact they received the vaccine as adolescents. Another potential explanation for this finding is the possibility that participants may have confused the combined pertussis-diphtheria-tetanus vaccine with the tetanus or tetanus-diphtheria vaccine. While the aNICS is the only evaluation of vaccine coverage at a national level in Canada, one must interpret the results cautiously as the aNICS may not be representative of the population because of low response rates and selection and information biases.3,37

Attitudes and beliefs in this sample were generally vaccine-positive, although participants were seemingly unfamiliar with which vaccines are recommended for them. The majority of participants reported believing that infectious diseases pose a serious threat to the health of adults, but far fewer believed themselves to be at significant risk of catching influenza, meningitis, and pertussis. The Health Belief Model used to inform the survey instrument posits that, among other beliefs, the belief that somebody is susceptible to a disease increases their likelihood of engaging in a health behavior (i.e., vaccination).28 Multivariable analyses did not reveal such a relationship in this study.

Despite most participants reporting that they have enough information to decide whether or not to be vaccinated study. Having been offered vaccines against influenza, and that vaccines are easily accessible to them, 19.0% of the sample was still uncertain about whether or not they ought to be vaccinated. This is consistent with several behavior change theories and corroborates Corace and Garbers’ claim that knowledge, while necessary, is insufficient to initiate change in vaccination behavior.38

Depending on the vaccine, increasing age and access to a family doctor (influenza), and awareness of and agreement with NACI recommendations (influenza and meningitis) were predictive of vaccination receipt among participants in this study. Having been offered vaccines against influenza, meningitis, and pertussis were predictive of receipt of these vaccines and therefore serve as a reminder of the importance of providers continuing to offer their patients all of the vaccines for which they are eligible.

Awareness, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors about pharmacists as immunizers

The proportion of participants who identified pharmacists as a source of vaccine-related information in our study (35.3%) was slightly below that of a geographically representative survey of Canadians (44.5%)11 but followed the same trends, with the most commonly identified source of vaccine-related information being the family doctor, followed by the internet, media, and pharmacists in that order. Most participants were aware that pharmacists could give the influenza vaccine, but very few knew that they are also able to administer the Tdap and meningococcal vaccines. Interestingly, neither the Tdap nor the meningococcal vaccines are publicly funded for pharmacists to administer. Pharmacists, therefore, may not be promoting or offering these vaccines, knowing that patients can receive them free of charge from other care providers.

Participants’ widespread confidence that pharmacists have enough training to administer vaccines in our study is in keeping with recent findings from a study of Nova Scotian patients who received vaccines in community pharmacies.39 These are in contrast to the qualitative findings of MacDougall et al. wherein focus group participants expressed concern that pharmacists might not be able to attend to adverse events requiring emergency attention.11 Perhaps the apprehension about pharmacists’ credentials to immunize has become allayed as the public has become increasingly aware of the rigorous training that pharmacists receive to be eligible to vaccinate.11 Interestingly, despite confidence in pharmacists’ ability to vaccinate, nearly one-half of the participants would still feel more comfortable getting vaccinated by a pharmacist if another practitioner (i.e., nurse or doctor) recommended it to them. Furthermore, less than one-half of the participants actually ever received a vaccine from a pharmacist.

Frequent visits to the pharmacy and identifying pharmacists as sources of vaccine-related information were predictive of feeling that it was both comfortable and convenient to be vaccinated by a pharmacist and that pharmacists have enough training to give vaccines. This suggests that those who are aware of and actively accessing pharmacists as immunizers are likely to continue to do so because of their positive experiences. These findings are congruent with a survey of patients immunized by pharmacists in Toronto, ON, the majority of whom reported being very comfortable receiving the influenza vaccine from their pharmacist, and very satisfied with their pharmacists’ injection technique.40 Results from a quality assurance questionnaire distributed to Nova Scotian patients postvaccination by pharmacists also revealed predominantly positive experiences among respondents receiving an influenza vaccine from a pharmacist.39 Almost one-half of the participants indicated that their experience was better in the pharmacy than in other settings because of how convenient, fast, and efficient it was and how competent and knowledgeable the pharmacists were.39

Willingness to pay

Influenza vaccine is provided free of charge by pharmacists for individuals with a Nova Scotia health card. It costs approximately 60 CAD to obtain the high-dose influenza vaccine from a pharmacist, 70 CAD for the pertussis vaccine, and 170 CAD each for the MenB and MenACWY. This cost includes a35 CAD average assessment and injection fee that may or may not be covered by private insurance plans. Cost has been identified as a potential barrier to pharmacists as immunizers.11,41 Less than one-quarter of participants in our study would be willing to pay 25 CAD or more for a vaccine. These findings suggest that funding schedules that completely subsidize the provision of vaccinations by pharmacists would be successful in achieving the highest vaccine uptake. As price increases beyond 25 CAD, willingness to receive the vaccines would lessen. Beyond random variation, we do not know why more participants were willing to pay 200 CAD than 150 CAD and 100 CAD than 75 CAD. This reluctance to pay for vaccines is antithetical to other common preventive interventions that Canadians pay for, such as infant car seats, sunscreen, and bicycle helmets.41 Scheifele and colleagues suggest that there is a widespread perception by the public that only those vaccines provided to them free of charge are beneficial and that unfunded vaccines are of limited value.41 This perception is evidence of a bias against vaccines compared to other interventions (preventive and otherwise) that needs to be mitigated.41

Limitations

Although we received just under 1000 responses, the survey was lengthy and may have discouraged more participation by the public. There was overrepresentation of the younger demographic compared to the census profile for Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Canada, and our sample was highly educated compared to both Nova Scotian, New Brunswicker, and Canadian statistics.42 These discrepancies might be related to the online nature of the survey or because we sent an email to several universities as part of our recruitment strategy. These results, therefore, may not be generalizable to an older or less educated demographic, nor are they necessarily representative of the provincial or national population.

Compared to provincial and national statistics, the survey sample was also disproportionately female; this is a limitation in as much as these results may not reflect the experiences of men or gender-diverse people.43

As with all surveys, this one was susceptible to a social desirability bias despite assurances that the responses would remain anonymous. Other response biases could have also occurred as participants were asked to self-report receipt of vaccines.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that pharmacists are well-positioned to improve vaccine coverage and communicate vaccine-related information to recipients because of their convenient locations and the frequency with which members of the general public visit pharmacies. Pharmacists can administer a range of adult immunizations in Canada but are underutilized because of a lack of awareness among the general public about which vaccines they are trained and able to administer. Another contributor to the underutilization of pharmacists as immunizers may be the underlying hesitancy of individuals who would still prefer another healthcare provider give them a recommendation first. Furthermore, only the influenza vaccine is available free of charge from the pharmacy. As a result, pharmacists may not be highlighting or offering other vaccines that they are regulated to administer, because the public can get those vaccines free of charge from other, more traditional healthcare providers.

Interventions aimed at improving vaccine uptake must be implemented at the individual, family, community, and policy levels. Traditional providers must continue to offer their patients vaccines for which they are eligible and endorse pharmacists as immunizers in an effort to improve vaccine uptake. Concerns about cost require systematic change to ensure that pharmacists are able to provide vaccines to the public under the same funding model as other healthcare providers. Importantly, pharmacists are only able to improve vaccine uptake among those people who are aware that they can administer vaccines, and who are able to access them readily. There is an ongoing need for research into how else we might improve the accessibility of immunization, especially among those without primary care providers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN), GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA, and Sanofi Pasteur Limited for funding this research. The authors would like to thank the other members of the Improve ACCESS Team for their contributions to the overall study.1 We would also like to acknowledge Heather Sampson, Jeff Scott, Joanne Langley, Kathryn Slater, Sarah DeCoutere, and Susan Bowles for reviewing our survey instrument for content validity.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) through the Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN), and through Collaborative Research Agreements with GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA, and Sanofi Pasteur Limited. All supporters were provided the opportunity to review this manuscript for factual accuracy, but the authors are solely responsible for final content and interpretation. The authors received no financial support or other form of compensation related to the development of the manuscript.

Note

Karina Top, Joanne Langley, Susan Bowles, Julie Bettinger, Nancy Waite, Kathryn Slayter, Fawziah Lalji, Janusz Kaczorowski, Beth Taylor and Shelly McNeil.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper other than those indicated in Funding.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2021.1913963.

Ethics

The research protocol was approved by Research Ethics Boards at St. Francis Xavier University (#22895), the Nova Scotia Health Authority (#1021559), and Horizon Health (RS 2016-2351).

References

- 1.National Advisory Committee on Immunization . Page 2: Canadian immunization guide: part 3 vaccination of specific populations. Canadian Immunization Guide. Published2018. [accessed 2019 Oct 21]. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-3-vaccination-specific-populations/page-2-immunization-of-adults.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao L, Young K, Gemmill I.. Summary of the NACI seasonal influenza vaccine statement for 2019–2020. Canada Commun Dis Rep. 2019;45(6):149–55. doi: 10.14745/ccdr.v45i06a01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Public Health Agency of Canada . Vaccine uptake in Canadian adults: results from the 2016 adult National Immunization Coverage Survey (ANICS). Ottawa (ON); 2018. [accessed 2019 Oct 21]. http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2018/aspc-phac/HP40-222-2018-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Government of Canada . Vaccine coverage goals and vaccine preventable disease reduction targets by 2025. 2019. [accessed 2019 Aug 9]. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/immunization-vaccine-priorities/national-immunization-strategy/vaccination-coverage-goals-vaccine-preventable-diseases-reduction-targets-2025.html#1.0.

- 5.Public Health Agency of Canada . Final Report to Outcomes from the National Consensus Conference for Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in Canada. Vol 34S2; 2008; Quebec City. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colgrove J. Immunity for the people: the challenge of achieving high vaccine coverage in American history. Public Health Rep 2007;122(2):248–57. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson DR, Nichol KL, Lipczynski K. Barriers to adult immunization. Am J Med 2008;121(7):2. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan L. Adult vaccination: now is the time to realize an unfulfilled potential. Hum Vaccines Immunother 2015;11(9):2158–66. doi: 10.4161/21645515.2014.982998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canadian Pharmacists Association . Pharmacists play key role in achieving higher immunization rates in Canada. Canadian Pharmacists Association News; Published2015. [accessed 2019 Oct 21]. https://www.pharmacists.ca/education-practice-resources/patient-care/influenza-resources/pharmacists-role-in-flu-vaccination/. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ipsos . Canadians trust their doctors to make the right choice, but patients and doctors believe strongly that cost should come second to good health. Ipsos Health News.

- 11.MacDougall D, Halperin BA, Isenor J, MacKinnon-Cameron D, Li L, McNeil SA, Langley JM, Halperin SA. Routine immunization of adults by pharmacists: attitudes and beliefs of the Canadian public and health care providers. Hum Vaccines Immunother 2016;12(3):623–31. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1093714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houle SKD, Grindrod KA, Chatterley T, Tsuyuki RT. Publicly funded remuneration for the administration of injections by pharmacists: an international review. Can Pharm J 2013;146(6):353–64. doi: 10.1177/1715163513506369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kau L, Sadowski CA, Hughes C. Vaccinations in older adults: focus on pneumococcal, influenza and herpes zoster infections. Can Pharm J 2011;144(3):132–41. doi: 10.3821/1913-701X-144.3.132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson C, Thornley T. Who uses pharmacy for flu vaccinations? Population profiling through a UK pharmacy chain. Int J Clin Pharm 2016;38(2):218–22. doi: 10.1007/s11096-016-0255-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buchan SA, Rosella LC, Finkelstein M, Juurlink D, Isenor J, Marra F, Patel A, Russell ML, Quach S, Waite N, et al. Impact of pharmacist administration of influenza vaccines on uptake in Canada. Cmaj. 2017;189(4):E146–E152. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.151027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Isenor JE, Killen JL, Billard BA, McNeil SA, MacDougall D, Halperin BA, Slayter KL, Bowles SK. Impact of pharmacists as immunizers on influenza vaccination coverage in the community-setting in Nova Scotia, Canada: 2013-2015. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2016;9(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s40545-016-0084-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Isenor JE, Alia TA, Killen JL, Billard BA, Halperin BA, Slayter KL, McNeil SA, MacDougall D, Bowles SK. Impact of pharmacists as immunizers on influenza vaccination coverage in Nova Scotia, Canada. Hum Vaccines Immunother 2016;12(5):1225–28. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1127490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steyer TE, Ragucci KR, Pearson WS, Mainous AG. The role of pharmacists in the delivery of influenza vaccinations. Vaccine. 2004;22(8):1001–06. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirkdale CL, Nebout G, Megerlin F, Thornley T. Benefits of pharmacist-led flu vaccination. Ann Pharm Fr 2016;75(1):3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pharma.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canadian Pharmacists Association . Pharmacist’s role in flu vaccination. [accessed2019Oct23]. https://www.pharmacists.ca/education-practice-resources/patient-care/influenza-resources/pharmacists-role-in-flu-vaccination/.

- 21.Pharmacy Association of Saskatchewan . Flu shots 2019-2020. Published2019. [accessed 2019 Jun 7]. https://www.skpharmacists.ca/site/flu-shots.

- 22.Gentile D. Quebec pharmacists will soon be able to prescribe, administer vaccines. CBC News. 2019June [accessed 2019 Oct 21]. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/quebec-pharmacists-prescribe-administer-vaccines-1.5171890.

- 23.Morin P. New rules will let Yukon pharmacists deliver vaccines. CBC News. published2019May29 [accessed 2019 Jun 7]. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/new-rules-yukon-pharmacists-1.5153231.

- 24.New Brunswick Pharmacists’ Association . Flu shots at pharmacies gaining in popularity. Latest News. Published2014. [accessed 2020 Jul 14]. https://nbpharma.ca/news/9/page-4.

- 25.Statistics Canada . Population and dwelling count highlight tables, 2016 census. Census program 2016. [accessed2019Nov8] https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/hlt-fst/pd-pl/Table.cfm?Lang=Eng&T=101&S=50&O=A.

- 26.Ajzen I, Timko C. Correspondence between health attitudes and behavior. Basic Appl Soc Psych. 1986;7(4):259–76. doi: 10.1207/s15324834basp0704_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenstock IM. Why people use health services. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1966;44(3):94–127. doi: 10.2307/3348967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sugg Skinner C, Tiro J, Champion VL. Health belief model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K editors. Health behaviour: theory, research, and practice. 5th ed. San Fransisco (CA): Jossey-Bass A Wiley Brand; 2015. p. 75–94. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montaño DE, Kasprzyk D. Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K editors. Health behaviour: theory, research, and practice. 5th. San Fransisco (CA): Jossey-Bass A Wiley Brand; 2015. p. 95–124. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode survyes: the tailored design method. 4th. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halperin BA, MacDougall D, MacKinnon-Cameron D, Li L, McNeil SA, Langley JM, Halperin SA. Universal tetanus, diphtheria, acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccination of adults: what the Canadian public knows and wants to know. Vaccine. 2015;33(48):6840–48. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Macdougall D, Halperin BA, Mackinnon-Cameron D, Li L, McNeil SA, Langley JM, Halperin SA. Universal tetanus, diphtheria, acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccination of adults: what canadian health care providers know and need to know. Hum Vaccines Immunother 2015;11(9):2167–79. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1046662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schneeberg A, Bettinger JA, McNeil S, Ward BJ, Dionne M, Cooper C, Coleman B, Loeb M, Rubinstein E, McElhaney J, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and behaviours of older adults about pneumococcal immunization, a Public Health Agency of Canada/Canadian Institutes of Health Research Influenza Research Network (PCIRN) investigation. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1). doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.SAS . SAS Software. 2013.

- 35.King JP, McLean HQ, Belongia EA. Validation of self-reported influenza vaccination in the current and prior season. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2018;12(6):808–13. doi: 10.1111/irv.12593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacDougall DM, Langley JM, Li L, Ye L, MacKinnon-Cameron D, Top KA, McNeil SA, Halperin BA, Swain A, Bettinger JA, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of university students, faculty, and staff during a meningococcal serogroup B outbreak vaccination program. Vaccine. 2017;35(18):2520–30. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Government of Canada . Vaccination coverage and registries. Published2019. [accessed 2019 Aug 16]. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/immunization-coverage-registries.html#a1.

- 38.Corace K, Garber G. When knowledge is not enough: changing behavior to change vaccination results. Hum Vaccines Immunother 2014;10(9):2623–24. doi: 10.4161/21645515.2014.970076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Isenor JE, Wagg AC, Bowles SK. Patient experiences with influenza immunizations administered by pharmacists. Hum Vaccines Immunother 2018;14(3):706–11. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1423930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Papastergiou J, Folkins C, Li W, Zervas J. Community pharmacist–administered influenza immunization improves patient access to vaccination. Can Pharm J 2014;147(6):359–65. doi: 10.1177/1715163514552557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scheifele DW, Ward BJ, Halperin SA, McNeil SA, Crowcroft NS, Bjornson G. Approved but non-funded vaccines: accessing individual protection. Vaccine. 2014;32(7):766–70. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Statistics Canada . Census profile, 2016 census: Nova Scotia [Province] and Canada [Country] (table). 2016 census. Published2017. [accessed 2019 Oct 25]. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/Page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=PR&Code1=12&Geo2=&Code2=&SearchText=NovaScotia&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&GeoLevel=PR&GeoCode=12&type=0.

- 43.Statistics Canada . Age and sex highlight tables, 2016 census - population by broad age groups and sex, Canada and economic regions. Statistics Canada. Published2017. [accessed 2021 Mar 15]. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/hlt-fst/as/Table.cfm?Lang=E&T=11.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.