ABSTRACT

Bone apatite is not hydroxyapatite (HAp), it is carbonate apatite (CO3Ap), which contains 6–9 mass% carbonate in an apatitic structure. The CO3Ap block cannot be fabricated by sintering because of its thermal decomposition at the sintering temperature. Chemically pure (100%) CO3Ap artificial bone was recently fabricated through a dissolution–precipitation reaction in an aqueous solution using a precursor, such as a calcium carbonate block. In this paper, methods of fabricating CO3Ap artificial bone are reviewed along with their clinical and animal results. CO3Ap artificial bone is resorbed by osteoclasts and upregulates the differentiation of osteoblasts. As a result, CO3Ap demonstrates much higher osteoconductivity than HAp and is replaced by new bone via bone remodeling. Granular-type CO3Ap artificial bone was approved for clinical use in Japan in 2017. Honeycomb-type CO3Ap artificial bone is fabricated using an extruder and a CaCO3 honeycomb block as a precursor. Honeycomb CO3Ap artificial bone allows vertical bone augmentation. A CO3Ap-coated titanium plate has also been fabricated using a CaCO3-coated titanium plate as a precursor. The adhesive strength is as high as 76.8 MPa, with excellent tissue response and high osteoconductivity.

KEYWORDS: Carbonate apatite, calcium carbonate, dissolution–precipitation reaction granules, honeycomb, coating

CLASSIFICATIONS: 30 Bio-inspired and biomedical materials, 211 Scaffold / Tissue engineering/Drug delivery

Graphical abstract

1. Bone apatite

Animals with a skeleton are classified as invertebrates or vertebrates. The skeleton of invertebrates is composed of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) and is likely derived from elements found in seawater. In contrast, vertebrates, including humans, have a skeleton of carbonate apatite [CO3Ap: Ca10-a(PO4)6-b(CO3)c] instead of CaCO3 [1–5].

A key difference between CaCO3 and CO3Ap skeletons is phosphorous. Phosphorous or phosphate is important in energy metabolism in the process of generating energy or adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Invertebrates can use phosphates present in seawater, even though their concentrations are low (1.3 μmol/L). However, vertebrates living on the land need to store phosphorous in the body. During evolution from invertebrates to vertebrates, bone became the storage organ of phosphorous in vertebrates. In other words, CO3Ap was chosen as bone apatite as a result of evolution from invertebrates to vertebrates.

CO3Ap or bone apatite should be amenable for use as artificial bone. However, sintered hydroxyapatite (HAp) instead of CO3Ap has been used as a typical artificial bone since the 1970s. This is because the thermal decomposition of CO3Ap begins at approximately 400°C, which prevents the fabrication of sintered CO3Ap. Recently, 100% chemically pure CO3Ap blocks were fabricated through a dissolution–precipitation reaction in an aqueous solution using a CaCO3 block as a precursor.

2. CO3Ap fabrication though dissolution–precipitation reaction using a precursor

There are three key requirements for compositional transformation through the dissolution–precipitation reaction. First, the solubility of the precursor should be higher than that of the final product. Second, any component that is lacking must be supplied from the aqueous solution. Third, precipitates or crystals of the final product should have the ability to interlock with one another to maintain the shape of the block.

CO3Ap is a thermodynamically stable phase under physiological conditions. It is not soluble under physiological conditions. Moreover, CO3Ap crystals can interlock. Many compounds are more soluble than CO3Ap, and thus can be precursors for the fabrication of CO3Ap through dissolution–precipitation reactions including CaCO3 [6–18], α-tricalcium phosphate [19–24], dicalcium phosphate dihydrate [25,26], and CaSO4 [27–30]. Moreover, a component that is lacking can be supplied from aqueous solution.

One of the ideal precursors is CaCO3. It has low solubility in aqueous solution at neutral pH and contains both calcium and carbonate. Chemically pure CaCO3 blocks can be easily fabricated by simply exposing calcium hydroxide [Ca(OH)2] compact to carbon dioxide (CO2) [eq. (1)].

| (1) |

The compositional transformation of CO3Ap from CaCO3 requires phosphate. The CaCO3 block needs to be immersed in a phosphate salt solution for this compositional transformation.

When CaCO3 is immersed in an aqueous solution, it dissolves and supplies Ca2+ and CO32- [eq. (2)]. If other ions are absent, the water becomes saturated with CaCO3. However, the situation is different when water contains PO43−. In that case, the phosphate salt aqueous solution can be supersaturated with respect to CO3Ap when both Ca2+ and CO32- are supplied by the dissolution of CaCO3. Thus, Ca2+, PO43−, and CO32- precipitate as CO3Ap [eq (3)], and the precipitated CO3Ap crystals interlock with one another. Continuous dissolution–precipitation reactions lead to the compositional transformation from CaCO3 to CO3Ap, maintaining the macroscopic structure of the precursor.

| (2) |

| (3) |

Other useful precursors are CaSO4 · 2H2O, α-tricalcium phosphate [α-TCP: Ca3(PO4)2], and dicalcium phosphate dihydrate [DCPD: CaHPO4 · 2H2O]. However, sulfate ions tend to remain in the apatitic structure when CaSO4 · 2H2O is used as a precursor. CO3Ap containing a small amount of HAp tends to form when α-TCP or DCPD are used as precursors because of the competitive reaction to form CO3Ap and HAp. Therefore, CaCO3 appears to be an ideal precursor. Fabrication of CO3Ap based on compositional transformation through a dissolution–precipitation reaction using CaCO3 as a precursor may have arisen during the evolution of vertebrates from invertebrates.

3. CO3Ap and bone remodeling

3.1. Bone remodeling process

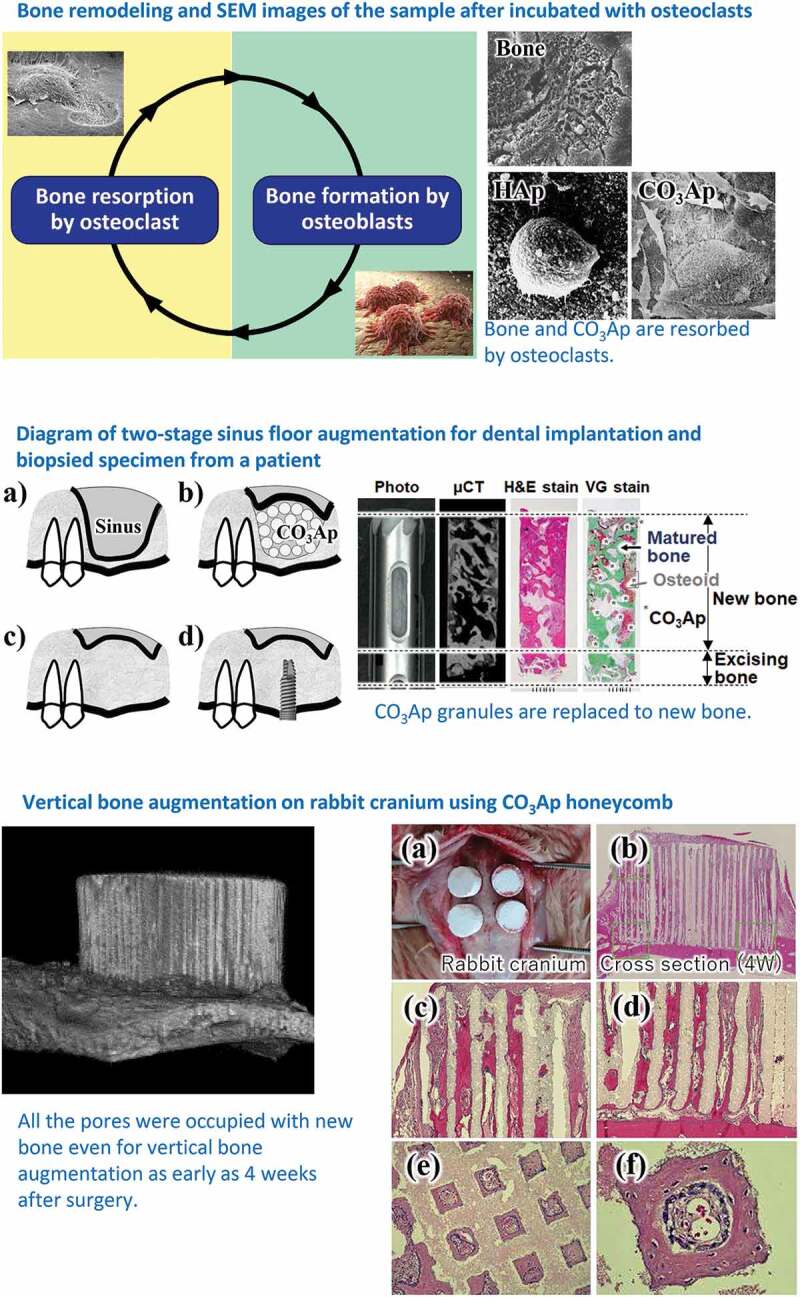

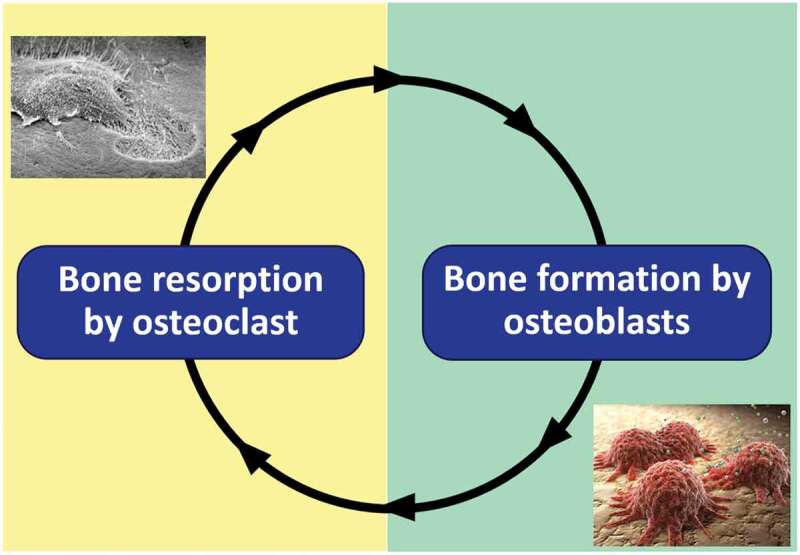

Bone remodeling involves the replacement of old bone and autograft by new bone. Osteoclasts resorb the old bone or autograft, followed by the formation of new bone by osteoblasts (Figure 1). Apatite is osteoconductive. Therefore, osteoblasts are active on their surfaces, although the degree of activity can differ depending on the type of apatite. The activity of osteoclasts also differs according to the type of apatite. Figure 2 displays representative scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of osteoclasts incubated on the surfaces of bone, HAp, and CO3Ap. The absence of osteoclastic resorption with HAp [6] is evidence that HAp cannot be replaced with new bone because osteoclast resorption does not occur. In contrast, osteoclastic resorption occurs for bone and CO3Ap.

Figure 1.

Graphical image of bone remodeling performed by osteoclasts and osteoblasts

Figure 2.

SEM images of bone, sintered HAp, and CO3Ap when osteoclasts were incubated on their surfaces [6]

Osteoclasts form Howship’s lacunae and decrease the pH inside the lacunae to pH 3–5, leading to the dissolution of bone apatite. Thus, osteoclasts resorb apatite by dissolving it using a weak acid (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Graphical image of osteoclasts

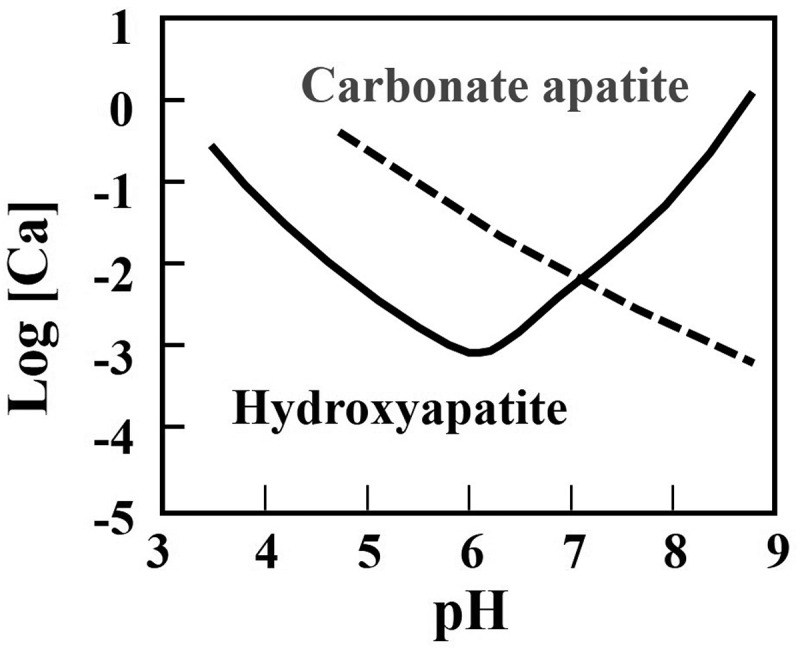

Figure 4 summarizes the solubilities of HAp and CO3Ap as a function of pH. At physiological pH or pH 7.4, CO3Ap is thermodynamically the most stable phase. This may explain why bone apatite is CO3Ap. However, under weakly acidic conditions produced by osteoclasts or at a pH of 3–5, the solubility of CO3Ap is higher than that of HAp. Therefore, CO3Ap dissolves in weakly acidic conditions and is resorbed by osteoclasts, whereas HAp does not appreciably dissolve under weakly acidic conditions and is not resorbed by osteoclasts.

Figure 4.

Solubility of carbonate apatite and hydroxyapatite in body fluid in terms of calcium concentration as a function of pH [14]

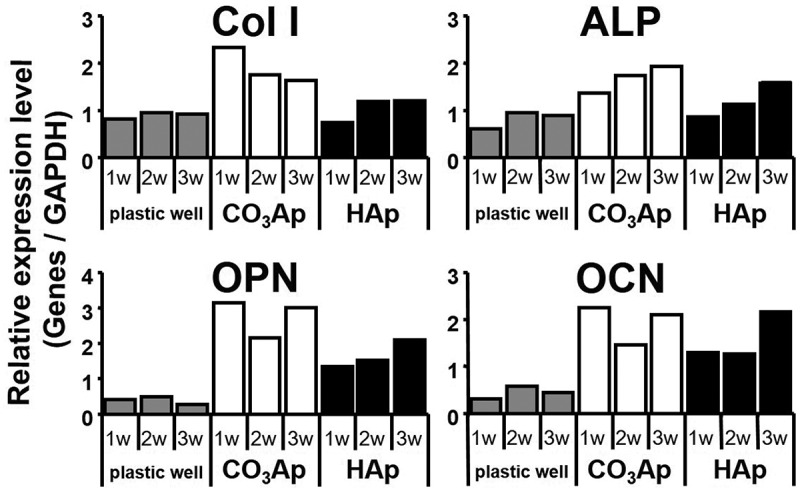

3.2. Differentiation of osteoblasts

Osteoblastic activity is the counterpart of osteoclastic activity in bone remodeling (Figure 3). One of the parameters of osteoblastic activity is differentiation. Osteoblastic differentiation markers include type I collagen, alkaline phosphatase, osteopontin, and osteocalcin (Figure 5) [31]. Human bone marrow cells (hBMCs) incubated on CO3Ap demonstrated much higher expression than HAp. Upregulation of osteoblast differentiation is likely one of the causes of the higher osteoconductivity of CO3Ap artificial bone, in addition to the activation of osteoblasts through cell-cell interactions with osteoclasts.

Figure 5.

Relative gene expression levels of type I collagen, alkaline phosphatase, osteopontin, and osteocalcin on the surface of plastic well, CO3Ap, and sintered HAp [31]

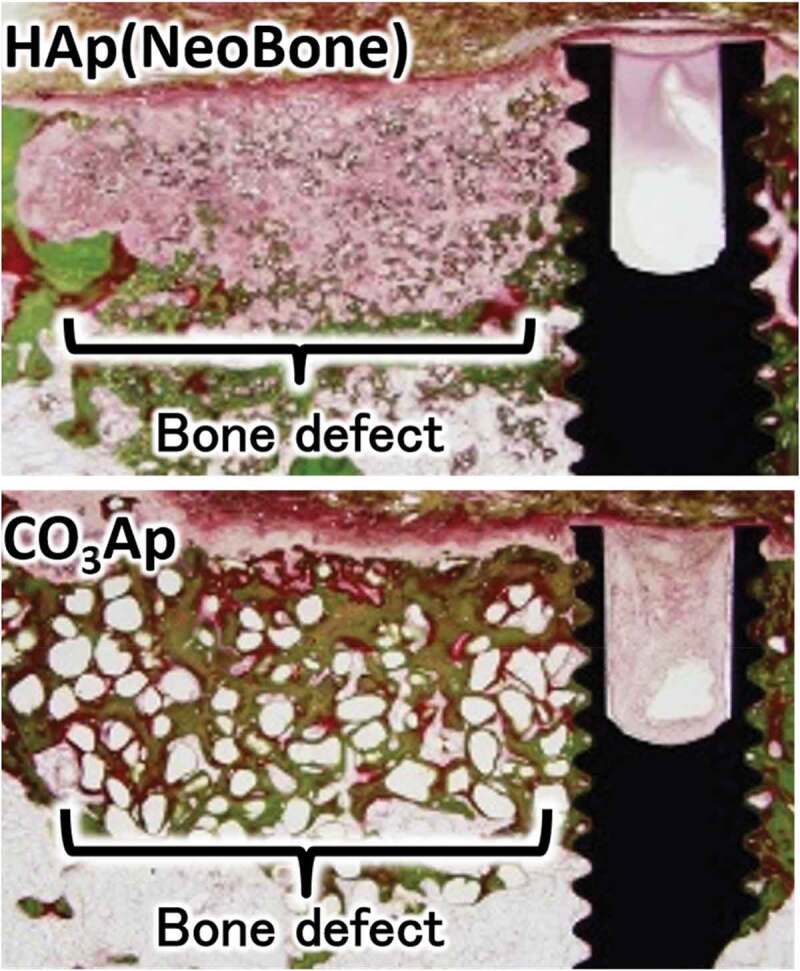

3.3. Histological findings

Figure 6 summarizes the representative results of Villanueva Goldner (VG) histologic staining comparison of CO3Ap and sintered HAp (Neobone®) used for reconstruction of mandibular bone defects adjacent to dental implants in beagle dogs 4 weeks after reconstruction surgery [32]. In VG staining, mature bone is stained green. Reconstruction of a defect with HAp involves the formation of only a limited amount of bone at the defect site, on the surface of the bone defect, and adjacent to the dental implant. This is one reason why no artificial bones have been approved for implant-related bone defect reconstruction surgeries in Japan. In contrast, more bone forms even at the center of bone defects reconstructed using CO3Ap. The surfaces of bone defects and dental implants become covered with bone. The documented bonding that results between bone, CO3Ap, and dental implant clearly indicating the usefulness of CO3Ap as an artificial bone for dental implants.

Figure 6.

VG-stained histological image of sintered HAp (Neobone®) and CO3Ap 4 weeks after reconstruction surgery of beagle dogs’ mandibular bone defect adjacent to a dental implant [32]

3.4. Clinical trials

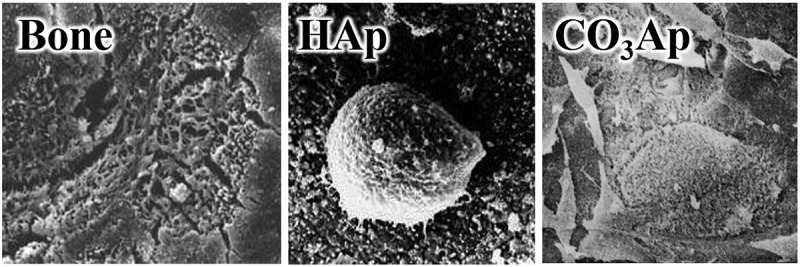

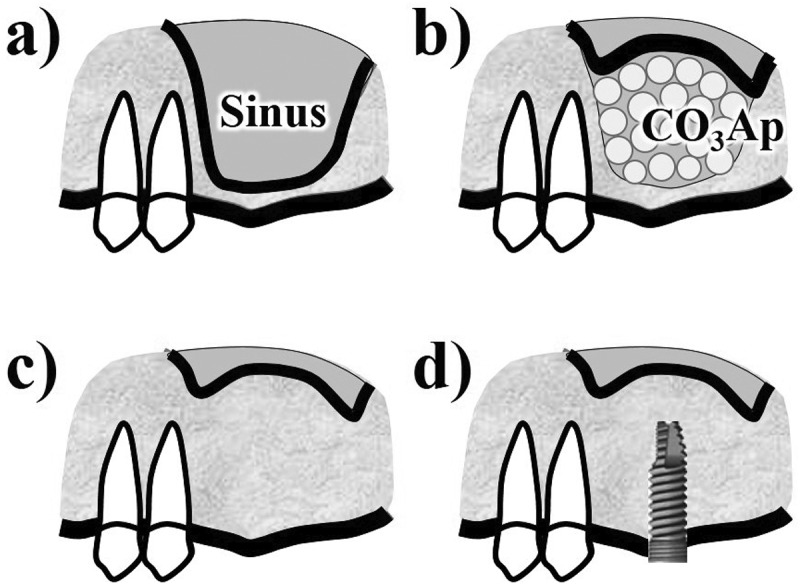

The first human clinical trial was performed at three university hospitals in patients requiring sinus floor augmentation [33,34]. Figure 7 illustrates the procedure for two-stage sinus floor augmentation [34]. After the sinus floor membrane was elevated with a mucosal elevator, CO3Ap granules were placed in the elevated space (Figure 7(b)). Implant placement was planned for 8 ± 2 months after the augmentation. Prior to implantation, a bone biopsy can be performed using a trephine bur (Figure 7(c)).

Figure 7.

Diagram of two-stage sinus floor augmentation for dental implantation. (a) before operation, (b) filling CO3Ap granule after elevation of sinus floor membrane, (c) before biopsy which was performed 8 ± 2 months after the surgery, (d) after dental implantation

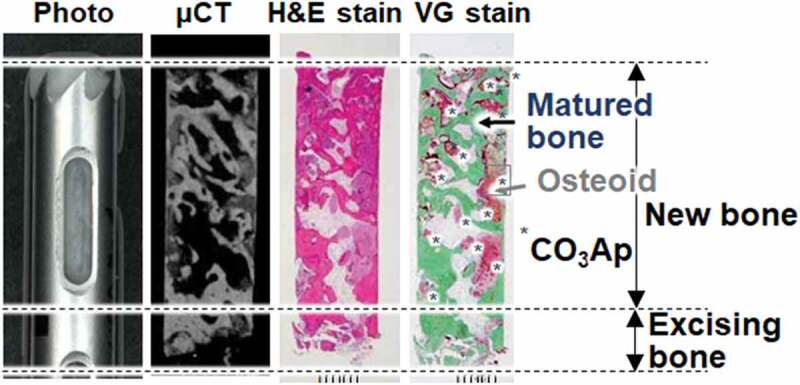

Figure 8 summarizes the micro-computed tomography (μ-CT) images and the appearance of biopsy tissue stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H-E) or VG. CO3Ap granules were replaced with new bone, even though a small amount of CO3Ap granules remain at this stage [34]. The presence of both mature bone and osteoids indicated active bone remodeling. Few inflammatory cells or foreign-body giant cells were observed in the biopsy specimens. The mean preoperative residual bone height of 3.4 ± 1.3 mm was increased to 13.0 ± 1.9 mm by the sinus floor augmentation using the CO3Ap granules. Since the height after sinus floor augmentation is sufficient for dental implants, all patients received dental implants without any problems [33,34]. Based on the trial results, CO3Ap granules were approved for clinical use as Cytrans Granules (GC Co, Tokyo, Japan) by the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) in 2017. The chemically pure CO3Ap granules are the first to be commercially available globally and the first artificial bone that can be used for bone reconstruction aimed at dental implantation in Japan.

Figure 8.

Photo, μ-CT scanning, H-E and VG staining of a histological specimen biopsied from a patient who underwent two-stage sinus floor augmentation for dental implantation [34]

4. CO3Ap honeycomb artificial bone

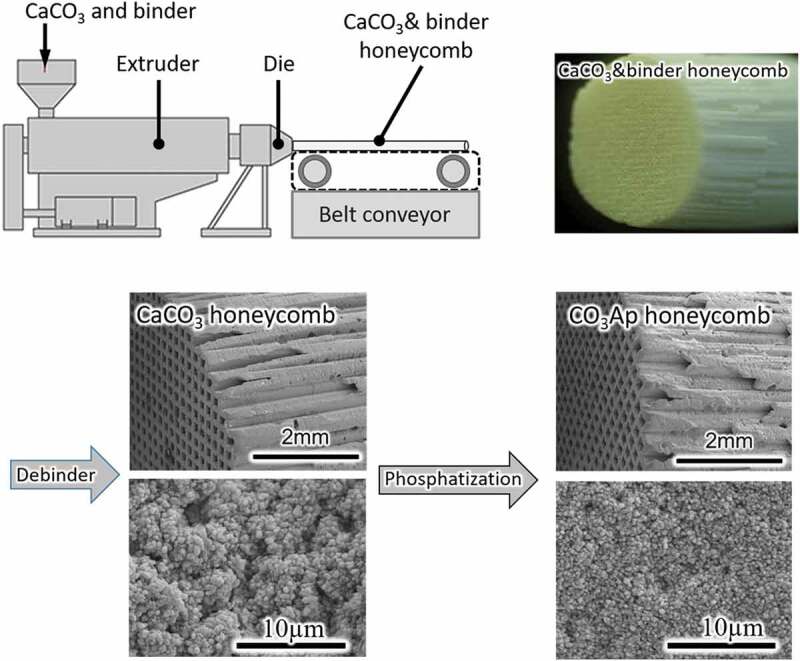

Not only composition but also architecture play important roles in governing the ability of artificial bone. In other words, regulation of architecture may be one of the important keys for artificial bone to demonstrate the similar osteoconductivity of autograft. One of the attractive architectures is the honeycomb. Fabrication of the CO3Ap honeycomb by the dissolution–precipitation reaction requires a precursor. In general, a honeycomb is fabricated by extruding a raw material through a honeycomb die (Figure 9). An organic binder is necessary for extrusion. Therefore, the organic binder must be eliminated in the subsequent debindering.

Figure 9.

Diagram of honeycomb fabrication process and SEM images of CaCO3 and CO3Ap honeycombs

The CaCO3 honeycomb becomes a CO3Ap honeycomb by immersion in a phosphate salt aqueous solution based on compositional transformation through a dissolution–precipitation reaction that maintains the honeycomb structure. Figure 9 shows typical SEM images of CaCO3 and CO3Ap honeycombs. The macroscopic honeycomb structure was maintained during the compositional transformation. However, the microstructure is changed during the dissolution–precipitation reaction, indicating a dependence on the crystal structure of each honeycomb composition.

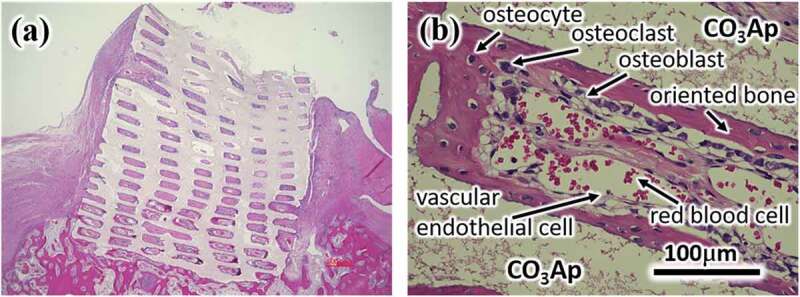

Figure 10 displays a representative histological image one month after reconstruction of the femoral bone defect using the CO3Ap honeycomb [13]. Tissue penetration into all pores of CO3Ap honeycomb is evident. At higher magnification, the new bone formation at the pore surface of CO3Ap honeycomb is evident. The presence of osteoclasts and osteoblasts on the surface of the newly formed bone indicates active bone remodeling. Osteocytes are also observed within the bone matrix. Interestingly, numerous vascular endothelial cells and red blood cells are found inside the pores, indicating the formation of blood vessels [12].

Figure 10.

H-E stained histological image 4 weeks after rabbit femoral bone defect was reconstructed using a CO3Ap honeycomb [13]. The (b) is a locally magnified photograph of (a)

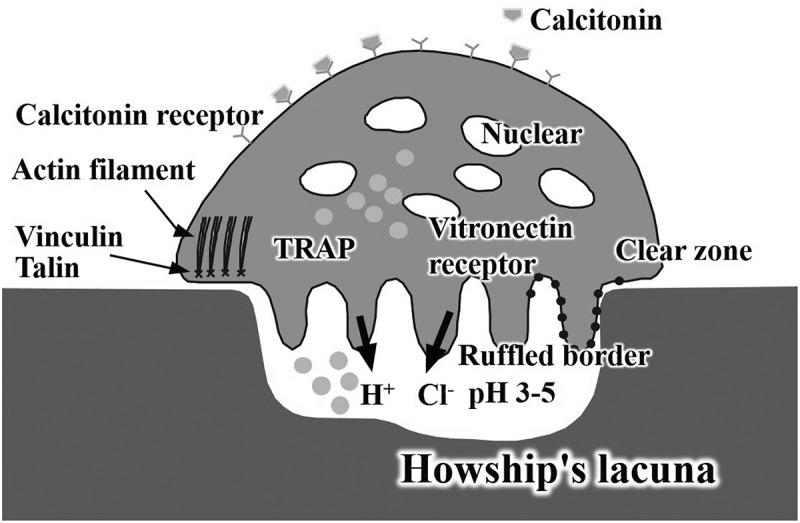

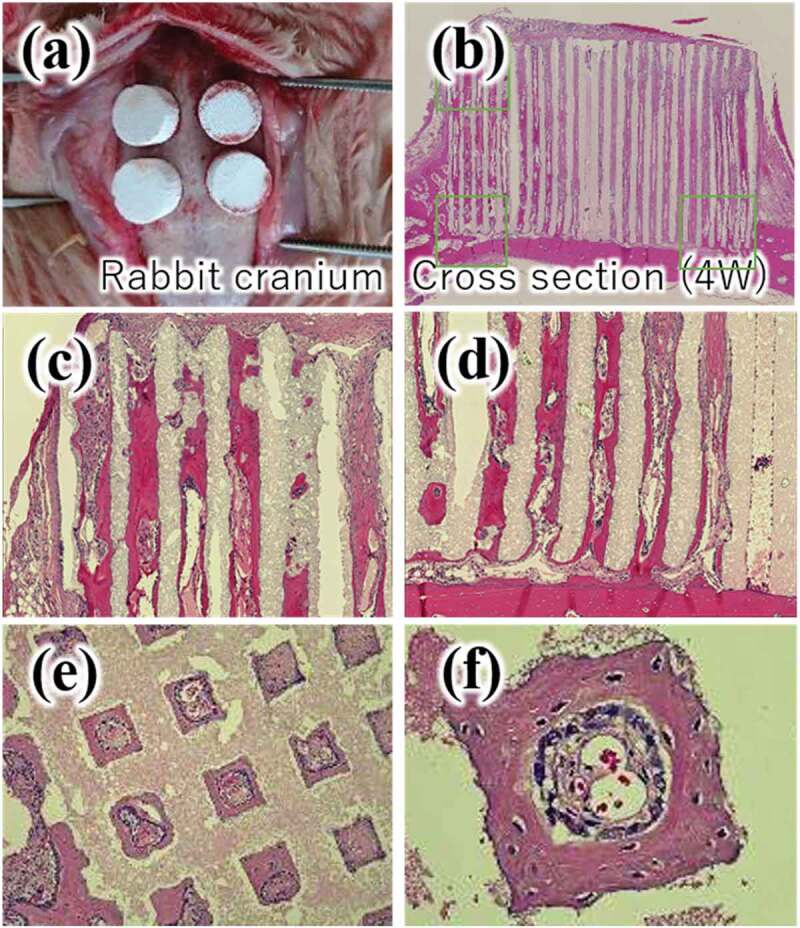

Vertical bone augmentation can be performed using the CO3Ap honeycomb. Figure 11 summarizes the results of vertical bone augmentation on rabbit cranium. New bone formation was confirmed 4 weeks after implantation, even at the top of the CO3Ap honeycomb (Figure 11(b)). Magnified images of the top (Figure 11(c)) and bottom (Figure 11(d)) parts of the CO3Ap honeycomb along the pores, cross section of the CO3Ap honeycomb at mid-height (Figure 11(e)), and new bone formation at the pore surface of the CO3Ap honeycomb (Figure 11(f)) are shown. The same histological results were obtained for vertical bone augmentation as for femoral bone defect augmentation. Osteoclasts, osteoblasts, and osteocytes were also observed. In addition, numerous vascular endothelial cells and red blood cells were found inside the pores.

Figure 11.

Implantation procedure (a) and H-E stained histological images, (b)-(f), 4 weeks after vertical bone augmentation on rabbit cranium [13]. (c) top of the CO3Ap honeycomb, (d) bottom parts of the CO3Ap honeycomb, (e) CO3Ap honeycomb at mid-height, (f) higher magnification of (e)

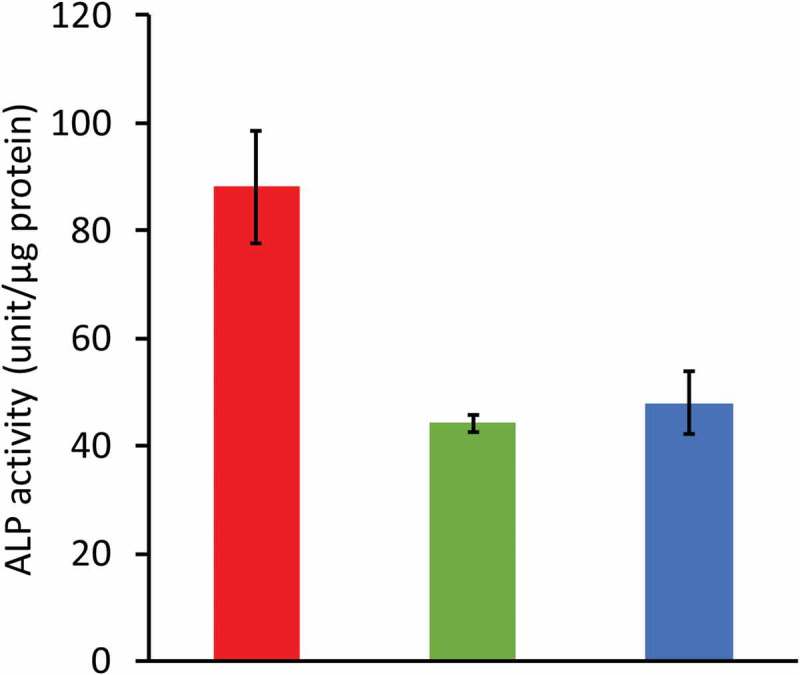

A comparison of the cell and tissue responses among the CO3Ap, HAp, and β-TCP honeycombs has also been reported [35]. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity is an index of osteoblast maturation. ALP activity of MC3T3-E1 cells 7 days following seeding was approximately two-fold higher for the CO3Ap honeycomb than for β-TCP and HAp honeycombs (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Effects of honeycomb’s composition on MC3T3-E1 cell differentiation in vitro. ALP activity of cells cultured for 7 days on CO3Ap, HAp, and β-TCP honeycombs [35]

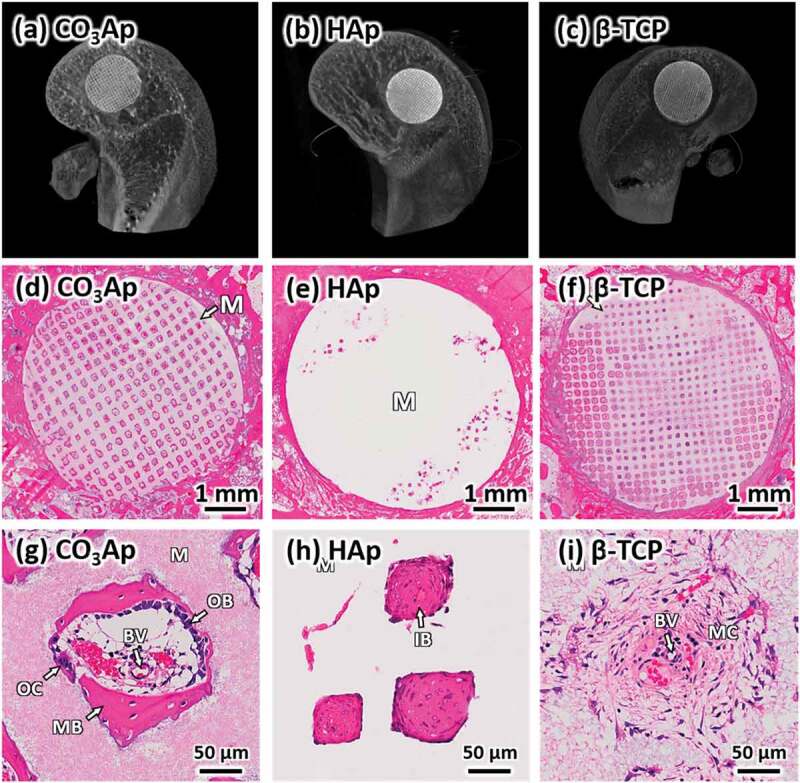

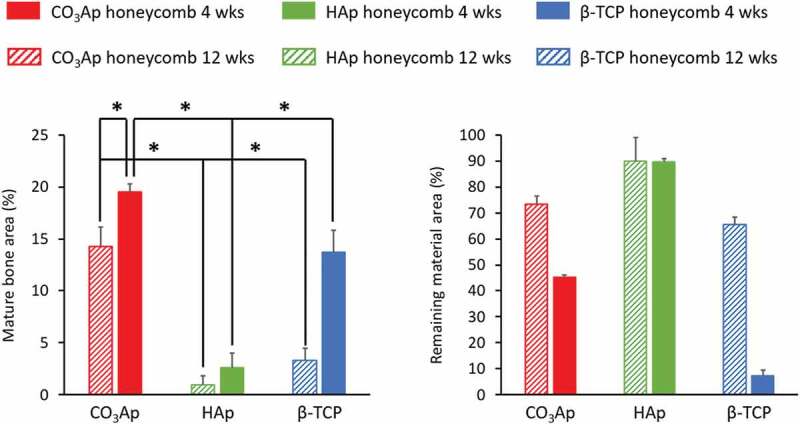

Figure 13 summarizes μ-CT and H-E stain histological findings 4 weeks after bone defects made at the distal epiphysis of rabbit femurs were reconstructed with CO3Ap, HAp, and β-TCP honeycombs [35]. In the case of the CO3Ap honeycomb, new mature bone formed along the walls surrounding the macropores. Osteoblasts were detected along the new bone, osteoclasts were detected on the material surface, and blood vessels were detected in the macropores (Figure 13(c),Figure 13(g)). In the HAp honeycomb, immature bone, but not mature bone, was observed in only a small portion of the macropores at 4 weeks post-operation (Figure 13(e,Figure 13(h)). Osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and blood vessels were not observed in any macropores in the HAp honeycomb, whereas these cells and tissues were present in every macropore examined in the CO3Ap honeycomb. Even at 12 weeks after surgery, almost all macropores were occupied by immature bone, and osteoblasts and osteoclasts were not observed in the macropores. In the case of β-TCP honeycomb 4 weeks after surgery, almost all macropores were filled with mesenchyme, and no osteoblasts or osteoclasts were observed in the macropores (Figure 13(f,Figure 13(i)). New mature bone formation was observed within a small portion of macropores. The area of mature bone at 4 and 12 weeks after surgery is summarized in Figure 14 along with the remaining mineral area. The area of mature bone area was significantly larger for CO3Ap honeycomb compared to that of HAp and β-TCP honeycombs. Remaining materials area was largest for HAp honeycomb followed by CO3Ap honeycomb and β-TCP honeycomb for both 4 and 12 weeks after surgery.

Figure 13.

μ-CT images, (a–c), and HE-stained histological images, (d-i), of bone defects 4 weeks after reconstruction with CO3Ap (a, d, g), HAp (b, e, h), and β-TCP (c, f, i) honeycombs. ‘OB,’ ‘OC,’ ‘MB,’ ‘IB,’ ‘MC,’ ‘M,’ ‘BV,’ and ‘AC’ indicate osteoblast, osteoclast, new mature bone, immature bone, mesenchyme, material, blood vessel, and adipose cell, respectively [35]

Figure 14.

Mature bone area and remaining material area of bone defects 4 and 12 weeks after reconstruction with CO3Ap, HAp, and β-TCP honeycombs. *p < 0.05 [35]

5. CO3Ap coated titanium plate

Titanium (Ti) is used as an implant device because of its high mechanical strength and ease of osseointegration [36,37]. In particular, surface-roughed Ti implants demonstrate greater osseointegration and a higher implantation success rate. However, osteogenesis of Ti, even with a roughened surface, is poorer than that of osteoconductive materials like apatite. Therefore, initial loosening of Ti implants is a problem for early loading [38, 39, 40].

Ti roughened surface coated with CO3Ap may be an ideal Ti implant because of its pronounced osteoconductivity and replacement by new bone. CO3Ap coated Ti (CO3Ap–Ti) can be fabricated by compositional transformation through a dissolution–precipitation reaction using calcite-coated titanium (CaCO3–Ti) as a precursor [39–41].

In this process, CaCO3–Ti is established on the roughened surface Ti by wetting the Ti with an ethanol solution of Ca(NO3)2, followed by heating at 550°C in a CO2 gas atmosphere. This results in the thermal decomposition of Ca(NO3)2 and its carbonation. CO3Ap–Ti is then fabricated through a dissolution–precipitation reaction in an aqueous solution of Na2HPO4 using CaCO3–Ti as a precursor.

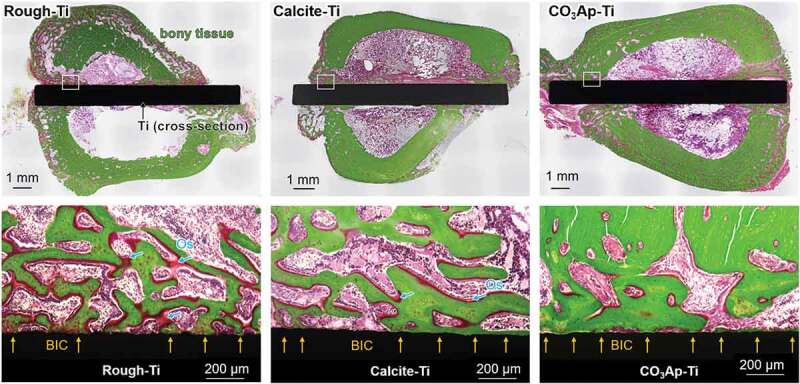

The adhesion strengths of CaCO3–Ti and CO3Ap–Ti are as high as 56.6 and 76.8 MPa, respectively. Figure 15 summarizes the VG-stained histological results 4 weeks after implantation in the straight defect of the proximal tibia 2 cm away from the knee joint in rabbits. Abundant mineralized bone formed on the surface of CO3Ap–Ti. In contrast, osteoid, rather than mineralized bone, was primarily present on the surface of the rough–Ti surface. The bone-implant contact percentages in CO3Ap–Ti to bone (72.9% ± 6.4%) exceeded those of rough–Ti to bone (48.2 ± 7.8%) and calcite–Ti to bone (59.9 ± 15.4%).

Figure 15.

Villanueva-Goldner-stained histological sections: general view, and high-magnification view of the cortical bone of sections in rough-Ti, calcite-Ti, and CO3Ap-Ti after 4 weeks of healing showing bone-implant contact (BIC) and osteoid (Os). Yellow arrows indicate BIC areas [41]

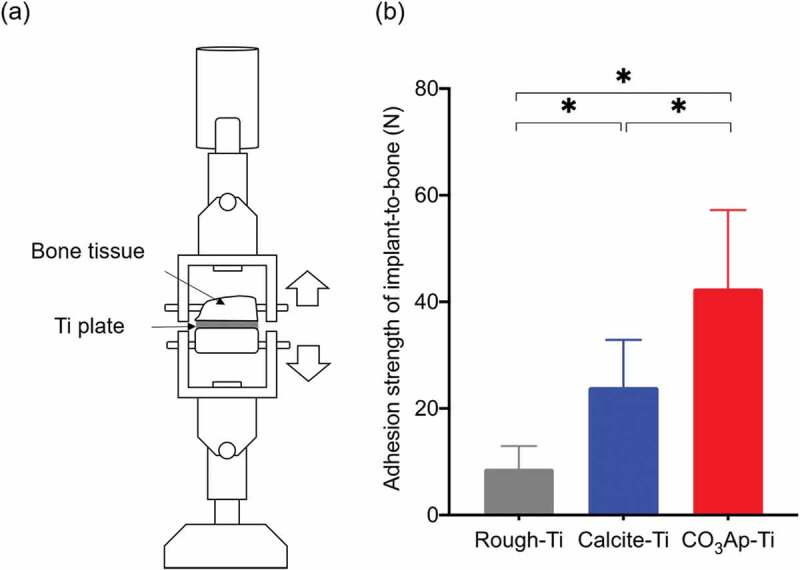

Figure 16 illustrates the detaching test used to measure the adhesion strength of the implant to the bone and the results. The increased bone-implant contact resulted in markedly greater adhesion strengths of CO3Ap–Ti to bone (42.5 ± 14.7 N) than that of rough-Ti to bone (8.7 ± 4.3 N) and calcite–Ti to bone (24.0 ± 8.9 N). Most of the fracture occurred between at the bone in the case of CO3Ap–Ti, whereas most of the fracture occurred at the interface between Ti plate and calcite for calcite–Ti, and interface between Ti plate and bone for rough-Ti. Very high bonding strength with bone and fracture at bone may be caused, at least in part, to the expansion of CO3Ap in the roughened Ti during the dissolution–precipitation reaction.

Figure 16.

Illustration of the (a) detaching test in bone harvested at 4 weeks after implantation of Ti plates in the tibia defects of rabbits, and (b) adhesion strength of bone-to-implant in rough-Ti, calcite-Ti, and CO3Ap-Ti (n = 8). *p < 0.05 for comparisons between the indicated groups [41]

The documented excellent tissue response, higher osteoconductivity, and higher adhesion strength guarantee the usefulness of CO3Ap–Ti for dental and orthopedic implants.

6. Conclusion

Chemically pure (100%) CO3Ap artificial bone can be fabricated by compositional transformation through a dissolution–precipitation reaction using a precursor. Although the results obtained to date are encouraging, little is known about CO3Ap artificial bone compared with other artificial bones, such as HAp and β-TCP.

Acknowledgments

This review was supported by AMED under Grant Number JP21im0502004h and JP20lm0203123h.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development [JP21im0502004h, JP20lm0203123h].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- [1].LeGeros RZ.Calcium phosphates in oral biology and medicine. Basel: Karger; 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Elliot JC.Calcium phosphate biominerals. Rev Miner Geochem. 2002;48:427–453. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Dorozhkin SV, Epple M. Biological and medical significance of calcium phosphates. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2002;41:3130–3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fleet M. Carbonated hydroxyapatite. Singapore: Pan Stanford Publishing Pte; 2015. ISBN: 978-981-4463-67-6. [Google Scholar]

- [5].LeGerous RZ, Ben-Nissan B. Introduction to synthetic and biologic apatites. In: Nissan B, editor. Advances in calcium phosphate biomaterials. Berlin: Springer; 2014. p. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ishikawa K. Bone substitute fabrication based on dissolution-precipitation reaction. Materials. 2010;3:1138. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ishikawa K, Matsuya S, Lin X, et al. Fabrication of low crystalline B-type carbonate apatite block from low crystalline calcite block. J Ceram Soc Jpn. 2010;118(5):341. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lee Y, Hahm YM, Matsuya S, et al. Characterization of macroporous carbonate-substituted hydroxyapatite bodies prepared in different phosphate solutions. J Mater Sci. 2007;42:7843–7849. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zaman CT, Takeuchi A, Matsuya S, et al. Fabrication of B-type carbonate apatite blocks by the phosphorylation of free-molding gypsum-calcite composite. Dent Mater J. 2008;27(5):710-–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Daitou F, Maruta M, Kawachi G, et al. Fabrication of carbonate apatite block based on internal dissolution-precipitation reaction of dicalcium phosphate and calcium carbonate. Dent Mater J. 2010;29(3):303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Maruta M, Matsuya S, Nakamura S, et al. Fabrication of low-crystalline carbonate apatite foam bone replacement based on phase transformation of calcite foam. Dent Mater J. 2011;30(1):14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sunouchi K, Tsuru K, Maruta M, et al. Fabrication of solid and hollow carbonate apatite microspheres as bone substitutes using calcite microspheres as a precursor. Dent Mater J. 2012;31(4):549–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ishikawa K, Munar ML, Tsuru K, et al. Fabrication of carbonate apatite honeycomb and its tissue response. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2019;107A:1014–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ishikawa K. Carbonate apatite bone replacement: learn from the bone. J Ceram Soc Jpn. 2019;127(9):595–601. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hayashi K, Munar ML, Ishikawa K. Carbonate apatite granules with uniformly sized pores that arrange regularly and penetrate straight through granules in one direction for bone regeneration. Ceram Int. 2019;45(12):15429–15434. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Fujisawa K, Akita K, Fukuda N, et al. Compositional and histological comparison of carbonate apatite fabricated by dissolution-precipitation reaction and Bio-Oss®. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2018;29:121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hayashi K, Kishida R, Tsuchiya A, et al. Carbonate apatite micro-honeycombed blocks generate bone marrow-like tissues as well as bone. Adv Biosyst. 2019;3:1900140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tanaka K, Tsuchiya A, Ogino Y, et al. Fabrication and histological evaluation of a fully interconnected porous CO3Ap block formed by hydrate expansion of CaO granules. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2020;3:8872–8878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wakae H, Takeuchi A, Udoh K, et al. Fabrication of macroporous carbonate apatite foam by hydrothermal conversion of α-tricalcium phosphate in carbonate solutions. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2018;87(4):957–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Takeuchi A, Munar ML, Wakae H, et al. Effect of temperature on crystallinity of carbonate apatite foam prepared from α-tricalcium phosphate by hydrothermal treatment. Biomed Mater Eng. 2019;19(2–3):205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Karashima S, Takeuchi A, Matsuya S, et al. Fabrication of low-crystallinity hydroxyapatite foam based on the setting reaction of alpha-tricalcium phosphate foam. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;88(3):628–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sugiura Y, Tsuru K, Ishikawa K. Fabrication of carbonate apatite foam based on the setting reaction of α-tricalcium phosphate foam granules. Ceram Int. 2016;42:204–210. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Arifta TI, Munar ML, Tsuru K, et al. Fabrication of interconnected porous calcium-deficient hydroxyapatite using the setting reaction of α tricalcium phosphate spherical granules. Cerams Int. 2017;43:11149–11155. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ishikawa K, Arifta TA, Hayashi K, et al. Fabrication and evaluation of interconnected porous carbonate apatite from alpha tricalcium phosphate spheres. J Biomed Mater Res. 2019;107(2):269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tsuru K, Kanazawa M, Yoshimoto A, et al. Fabrication of carbonate apatite block through a dissolution–precipitation reaction using calcium hydrogen phosphate dihydrate block as a precursor. Materials. 2017;10(4):374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kanazawa M, Tsuru K, Fukuda N, et al. Evaluation of carbonate apatite blocks fabricated from dicalcium phosphate dihydrate blocks for reconstruction of rabbit femoral and tibial defects. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2017;28(6):85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lowmunkong R, Sohmura T, Takahashi J, et al. Transformation of 3DP gypsum model to HA by treating in ammonium phosphate solution. J Biomed Mater Res Part B. 2007;80B:386–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lowmunkong R, Sohmura T, Suzuki Y, et al. Fabrication of freeform bone-filling calcium phosphate ceramics by gypsum 3D printing method. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2009;90(2):531–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Nomura S, Tsuru K, Matsuya S, et al. Fabrication of carbonate apatite block from set gypsum based on dissolution-precipitation reaction in phosphate-carbonate mixed solution. Dent Mater J. 2014;33(2):166–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ayukawa Y, Suzuki Y, Koyano K, et al. Histological comparison in rats between carbonate apatite fabricated from gypsum and sintered hydroxyapatite on bone remodeling. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:Article ID 579541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Nagai H, Fujioka-Kobayashi M, Fujisawa K, et al. Effects of low crystalline carbonate apatite on proliferation and osteoblastic differentiation of human bone marrow cells. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2015;26(2):99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Mano T, Akita K, Fukuda N, et al. Histological comparison of three apatitic bone substitutes with different carbonate contents in alveolar bone defects in a beagle mandible with simultaneous implant installation. J Biomed Mater Res. 2020;108(4):1450–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kudoh K, Fukuda N, Kasugai S, et al. Maxillary sinus floor augmentation using low-crystalline carbonate apatite granules with simultaneous implant installation: first-in-human clinical trial. J Oral Maxil Surg. 2019;77(5):985.e1–985.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Nakagawa T, Fukuda N, Kasugai S, et al. Application of low crystalline carbonate apatite granules in two-stage sinus floor augmentation: a prospective clinical trial and histomorphometric evaluation. J Periodont Imp Sci. 2019;49(6):382–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hayashi K, Kishida R, Tsuchiya A, et al. Honeycomb blocks composed of carbonate apatite, β-tricalcium phosphate, and hydroxyapatite for bone regeneration: effects of composition on biological responses. Mater Today Bio. 2019;4:100031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Babbush CA, Kent JN, Misiek JD. Titanium Plasma-sprayed (TPS) Screw Implants for the reconstruction of the edentulous mandible. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;44:274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Cochran DL, Buser D, ten Bruggenkate CM, et al. The use of reduced healing times on ITI® implants with a sandblasted and acid-etched (SLA) surface: early results from clinical trials on ITI® SLA implants. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2002;13:144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Albrektsson T, Branemark PI, Hansson HA, et al. Osseointegrated titanium implants. Requirements for ensuring a long-lasting, direct bone-to-implant anchorage in man. Acta Orthop Scand. 1981;52:155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Shi R, Sugiura Y, Tsuru K, et al. Fabrication of calcite-coated rough-surface titanium using calcium nitrate. Surf Coat Tech. 2018;356:72–79. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Thi BL, Shi R, Long BD, et al. Biological responses of MC3T3-E1 on calcium carbonate coatings fabricated by hydrothermal reaction on titanium. Biomed Mater. 2020;15:035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Shi R, Hayashi K, Ishikawa K. Rapid osseointegration bestowed by carbonate apatite coating of rough titanium. Adv Mater Interfaces. 2020;7:2000636. [Google Scholar]