Abstract

Objectives:

To evaluate and compare perceived pain intensity, discomfort, and jaw function impairment during the first week with tooth-borne or tooth-bone–borne rapid maxillary expansion (RME) appliances.

Materials and Methods:

Fifty-four patients (28 girls and 26 boys) with a mean age of 9.8 years (SD 1.28 years) were randomized into two groups. Group A received a conventional hyrax appliance and group B a hybrid hyrax appliance anchored on mini-implants in the anterior palate. Questionnaires were used to assess pain intensity, discomfort, analgesic consumption, and jaw function impairment on the first and fourth days after RME appliance insertion.

Results:

Fifty patients answered both questionnaires. Overall median pain on the first day in treatment was 13.0 (range 0–82) and 3.5 (0–78) for groups A and B, respectively, with no significant differences in pain, discomfort, analgesic consumption, or functional jaw impairment between groups. Overall median pain on the fourth day was 9.0 (0–90) and 2.0 (0–71) for groups A and B, respectively, with no significant differences between groups. There were also no significant differences in pain levels within group A, while group B scored significantly lower concerning pain from molars and incisors and tensions from the jaw on day 4 than on the first day in treatment. There was a significant positive correlation between age and pain and discomfort on the fourth day in treatment. No correlations were found between sex and pain and discomfort, analgesic consumption, and jaw function impairment.

Conclusions:

Both tooth-borne and tooth-bone–borne RME were generally well tolerated by the patients during the first week of treatment.

Keywords: Rapid maxillary expansion, Pain and discomfort, Mini-implants, Questionnaire

INTRODUCTION

Rapid maxillary expansion (RME) is a common procedure in young children with a constricted maxilla and transverse discrepancies between the maxilla and the mandible.1,2 The primary goal of RME is to maximize dentofacial orthopedics and minimize orthodontic movement, but a recently published systematic review3 indicates that the skeletal effects (ie, the opening of the midpalatal suture) account for only approximately 20%–50% of the total screw expansion, meaning that the dentoalveolar effects in terms of molar tipping and alveolar bending account for over 50% of the total effect. To minimize these dental side effects, which likely increase the risk of relapse, skeletally anchored RME appliances have been introduced.4–6

Pain and discomfort are well-known side effects of orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances,7–9 but few studies10–12 have explored pain and discomfort during RME treatment. These few studies have concluded that most children undergoing RME report pain, which generally occurs during the initial phase and diminishes thereafter. The highest pain levels were reported during the first 10 activations and peaked on days 3 and 4. Activation protocols with two turns/d result in greater pain levels than do protocols with only one turn/d.11,13 With the introduction of skeletally anchored RME appliances, the question arises of how patients experience this new design, considering that they are mostly quite young. Earlier studies14,15 indicate that adolescent patients have very good tolerance of the insertion of mini-implant anchors both interradicularly and in the palate. These studies also concluded that age was not a predictor of pain and discomfort. To our knowledge, however, no studies have explored pain intensity and discomfort during treatment with skeletally anchored RME appliances.

The aim of this study was to evaluate and compare perceived pain intensity, discomfort, and jaw function impairment during the first week with tooth-borne or tooth-bone–borne RME (hybrid hyrax expander) appliances; we hypothesized that there would be no differences between these two RME treatment modalities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and Study Design

The regional ethical review board in Uppsala, Sweden, which follows the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, approved the study protocol (Dnr: 2009/334). After receiving oral and written information about the clinical trial, both the patients and their parents/guardians signed informed consent forms.

Fifty-four consecutive patients (28 girls and 26 boys) with a mean age of 9.8 years (SD 1.28 years) examined at the Postgraduate Dental Education Centre, Department of Orthodontics, Region Orebro County, Sweden, who met the eligibility criteria were recruited from September 2010 through December 2015 and participated in this study.

The following inclusion criteria had to be fulfilled by the participants enrolled in the study:

uni- or bilateral crossbite with constricted maxilla and

age at diagnosis of 8–13 years, with dental stage in the early or late mixed dentition.

Patients with previous or ongoing orthodontic treatment, craniofacial syndromes, or cleft lip or palate were considered ineligible for the study.

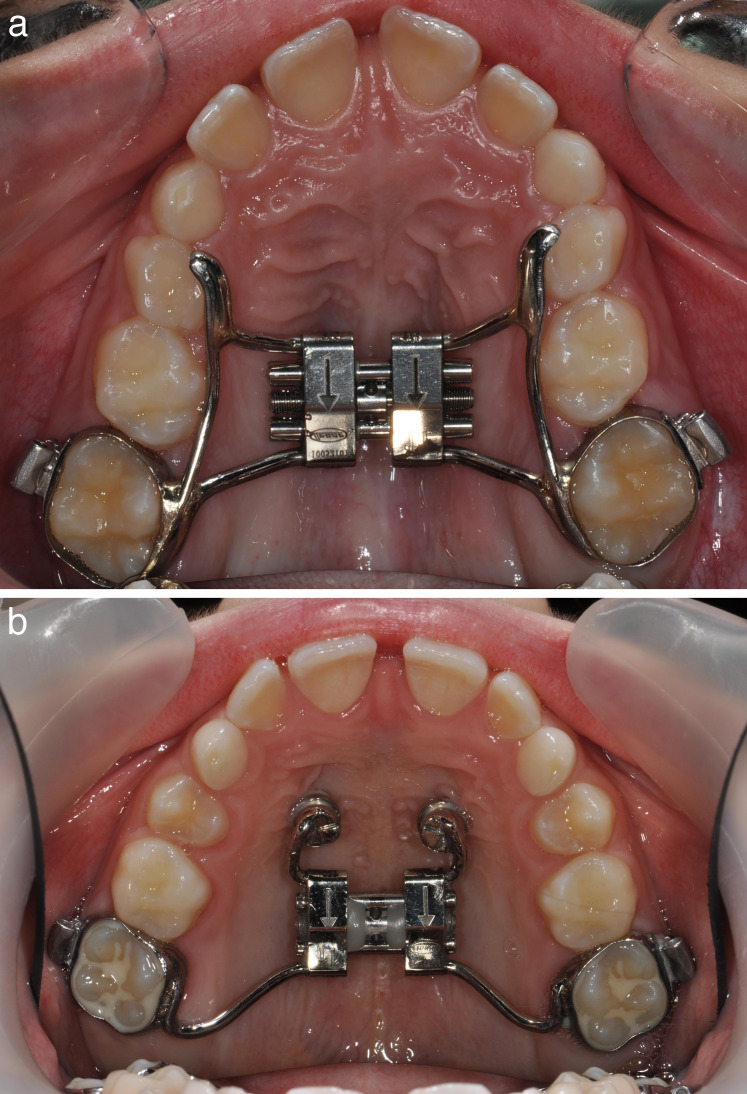

The randomization procedure was as follows: a computer-generated randomization list was created using SPSS software (version 17.0; SPSS, Chicago, Ill) and stored with a research secretary at the Postgraduate Dental Education Centre. Each time a patient gave his/her consent, the secretary was contacted by e-mail and the information about which type of expander the patient should receive was acquired. After informed consent was obtained from both patients and their parents/guardians, the patients were randomized into two groups: group A was treated with a conventional banded hyrax expander (n = 27) (Figure 1a) and group B with a hybrid hyrax expander with two 1.7 × 8–mm miniscrew implants (Orthoeasy®; Forestadent, Pforzheim, Germany) attaching the expander to the palate surface (n = 27) (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

(a) Conventional hyrax expander; (b) hybrid hyrax expander anchored on two mini-implants in the anterior palate.

Both expanders were activated two quarter turns per day (0.5 mm) until the palatal cusps of the maxillary first molars contacted the buccal cusps of the mandibular first molars. The patients were advised to use nonprescription analgesics at their own discretion. All patients in both groups were treated by the same orthodontist. The questionnaires were analyzed by one of the coauthors, who was blinded to the study and performed no orthodontic treatment on the patients.

Questionnaires

The questionnaires included self-report questions concerning pain intensity, discomfort, analgesic consumption, and jaw function impairment on the first and fourth days in treatment (Table 1). The questionnaires had previously been used in several studies16,17 and are considered to have ‘acceptable' to ‘good' reliability and internal consistency. The patients were asked to complete the questionnaires on their own after activation 1 day after (day 1) and 4 days after (day 4) the RME appliances were cemented. Approximately 10 minutes were needed to complete the questionnaires, the questions for which are presented in Table 1. Questions 1–9 concerning pain and discomfort were graded using a visual analogue scale (VAS) with the end phrases “no pain” and “worst pain imaginable” or “no discomfort” and “worst discomfort imaginable.” Question 10 had a binary “yes/no” response with follow-up questions (space was provided for written responses). Questions about jaw function impairment (questions 11–27) were assessed using a five-point scale with the alternatives “not at all,” “slightly difficult,” “difficult,” “very difficult,” and “extremely difficult.”

Table 1.

Self-Reported Questions Concerning Pain and Discomfort, Analgesic Consumption, and Daily Activities Assessed the First and Fourth Day After Placement of the Rapid Maxillary Expansion (RME) Appliances

| Pain intensity |

| 1. Do you now have pain? |

| 2. Do you now have pain from the molars? |

| 3. Do you now have pain from the incisors? |

| 4. Do you now have pain from the upper jaw? |

| 5. Do you now have pain from the palate? |

| 6. Do you now have pain from the tongue? |

| Discomfort |

| 7. Do you experience tensions in your upper jaw? |

| 8. Do you experience tensions in your teeth? |

| 9. Do you experience soreness from the appliance? |

| Analgesic consumption |

| 10. Have you used analgesics for pain from your jaws, teeth, or face? |

| If yes, what kind of analgesic and dosage did you use? |

| Jaw function impairment |

| If you now have pain or discomfort in your teeth and jaws, how much does that affect |

| 11. Your leisure time |

| 12. Your speech |

| 13. Your ability to take a big bite |

| 14. Your ability to chew hard food |

| 15. Your ability to chew soft food |

| 16. Your schoolwork |

| 17. Drinking |

| 18. Laughing |

| 19. Yawning |

| 20. Swallowing |

| Eating means taking a bite, chewing, and swallowing. How difficult is it for you to eat |

| 21. Crisp bread |

| 22. Meat |

| 23. Raw carrots |

| 24. Roll |

| 25. Peanuts |

| 26. Apples |

| 27. Cake |

In addition, three questions, modified for this study, were included in the questionnaire for the first day in treatment. These questions concerned the patient's experiences of pain and discomfort during the placement of the appliances and whether any moments were particularly unpleasant. The VAS was measured to the nearest 0.5 mm using a standard 100-mm metric ruler.

Statistical Analysis

Median value, interquartile range, and range were calculated for each variable. Differences between groups were tested using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test for pain and discomfort. Chi-square tests were used to determine differences between groups in functional jaw impairment, affected daily activities, and use of analgesics. Differences within groups were tested using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Differences with a P value of less than 5% (P < .05) were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Fifty of the enrolled 54 patients completed both questionnaires. One boy and one girl each in group A and group B did not submit their questionnaires despite several reminders. Consequently, group A consisted of 25 patients (ie, 12 boys and 13 girls) with a mean age of 9.7 years (SD 1.39 years), and group B comprised 25 patients (ie, 12 boys and 13 girls) with a mean age of 10.0 years (SD 1.16 years). There were no significant differences in age and gender between the two groups. The overall response rate was 91%.

Pain Intensity and Discomfort

Patient assessments of pain and discomfort during placement of the RME appliance were low overall and did not differ significantly between groups. Median values for pain were 8.0 (range 0–50) and 3.0 (0–82) for groups A and B, respectively, and median values for discomfort were 17.0 for both groups (range 0–63 and 0–100, respectively). Twenty-two of 50 study patients replied that they had experienced a particular part of the placement to be especially unpleasant, but with no significant difference between groups. The main complaint concerned pressure when the RME appliances were cemented.

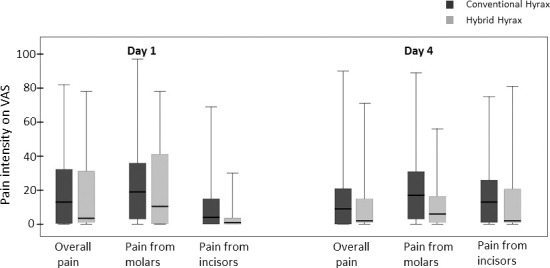

Overall pain and pain from molars and incisors on the first and fourth days in treatment are presented in Figure 2. There were no significant differences in pain levels between groups, although patients with the conventional hyrax appliance generally scored higher. There were also no significant differences in pain levels between days 1 and 4 in group A. Group B, however, scored significantly lower concerning pain from molars (P = .042) and incisors (P = .024) on day 4 compared with the first day in treatment. Pain levels from the jaw (M = 1.0 for both groups), palate (M = 2.0 for both groups), and tongue (M = 0 and 1.0, respectively, for groups A and B) were minor and did not differ significantly within or between groups.

Figure 2.

Median values, interquartile ranges, and ranges concerning pain intensity related to RME in the first week in treatment.

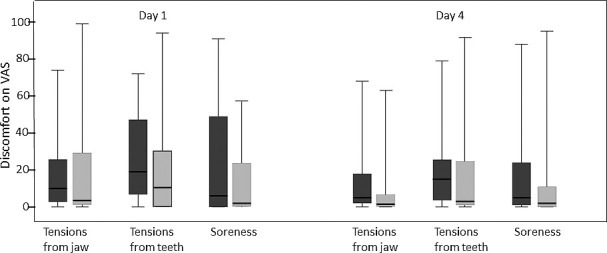

Discomfort values, expressed as tension and soreness on the first and fourth days in treatment, are presented in Figure 3. There were no significant differences in discomfort between groups. There were also no significant differences in discomfort between days 1 and 4 in group A, but group B scored significantly lower with regard to jaw tension (P = .001) on day 4.

Figure 3.

Median values, interquartile ranges, and ranges concerning discomfort related to RME in the first week in treatment.

Analgesic Consumption

Analgesic consumption was low and did not differ significantly within or between groups (Table 2). Paracetamol and ibuprofen were the most commonly used analgesics.

Table 2.

Analgesic Consumption the First and Fourth Day in Treatment

|

|

Group A (N = 25) |

Group B (N = 25) |

Total (N = 50) |

Group Difference |

| Analgesic the first day | 9 | 7 | 16 | NS |

| No analgesic the first day | 16 | 18 | 34 | NS |

| Total | 25 | 25 | 50 | |

| Analgesic the fourth day | 5 | 2 | 7 | NS |

| No analgesic the fourth day | 20 | 23 | 43 | NS |

| Total | 25 | 25 | 50 |

NS = Not significant

Jaw Function Impairment

Daily activities such as schoolwork and leisure time were generally not affected by treatment with RME appliances. However, several patients in both groups complained about great to extreme difficulties in eating hard food, meat, and crisp bread, but with no significant differences between groups.

Age and Gender

There were significant positive correlations between age and overall pain (P = .017), pain from incisors (P = .014), tension from teeth (P = .006), soreness (P = .028), and pain when laughing (P = .042), yawning (P = .030), and swallowing (P = .022) on the fourth day in treatment. There were very few gender differences in this study, although the girls complained more about tension from the teeth than did the boys (P = .048).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study comparing pain intensity and discomfort during RME treatment with a conventional hyrax appliance vs a skeletally anchored appliance. The most important finding was that there were no significant differences in pain and discomfort during the first week of RME treatment between groups. This is in agreement with our hypothesis and an important result when considering future RME treatment anchored on mini-implants.

Pain intensity levels reported here were low overall compared with those reported in studies examining pain during conventional RME treatment10,13 and pain in the first week with a fixed appliance,7–9 indicating that RME treatment, both conventional and skeletal, is well accepted by patients in this young age group. Analgesic consumption was consequently low.

The site with the highest pain scores in both groups was the first maxillary molars, which is logical because the appliances are connected to the molars and because the expansion pattern during RME results in dentoalveolar expansion (including dental tipping) being larger than skeletal expansion.3 Pain scores from the palate, however, were almost negligible in both groups, even though the appliance in group B was anchored on two miniscrews in the anterior palate.

The studied patients completed a questionnaire the day after the appliance was cemented (activation day 1) and on day 4. Earlier studies10,12 of pain during conventional RME treatment have stated that pain and discomfort levels peaked on days 3 and 4 and thereafter remained relatively constant. The present results, however, indicate significantly lower levels of pain from molars and incisors and of jaw tension on day 4 than on day 1 in the group with skeletally anchored appliances. It could be speculated that the center of applied force induced by each activation is closer to the midpalatal suture in the hybrid RME than the conventional appliance, which might relieve and minimize the magnitude of the force distributed to the dentition. This could explain why patients in the hybrid group experienced less pain and thus assigned lower scores.

From earlier studies14 we know that pain following miniscrew placement is concentrated in the first days after insertion and is almost negligible after 1 week. We therefore consider the risk of confounding factors due to miniscrew placement to be low because the patients in group B had their miniscrews placed 10–14 days before the appliance was cemented. Pain during placement also did not differ significantly between groups.

Median values of pain intensity and discomfort during the first week of RME treatment were low, but some patients described the pain and discomfort as the worst imaginable. Perception of pain intensity is subjective and is influenced by many factors, such as anxiety levels and motivational attitude.18 However, as the oral health of most studied patients was excellent, they had little or no experience with ordinary dental care, which could have contributed to the range of experienced pain intensity and discomfort.

There was no significant difference in pain levels between the groups in this study, although the values were generally lower in the skeletal group. This could be due to the force distribution mechanics discussed earlier.

Although some studies7,19 have reported that girls report more pain and discomfort than do boys, we found no major gender differences in experienced pain intensity and discomfort in this study. Interestingly, there was a positive correlation between age and overall pain, pain from incisors, tension from teeth, soreness, and pain when laughing, yawning, and swallowing, but only on the fourth day in treatment. With increasing age, interdigitation of the midpalatal suture increases,20 meaning that somewhat higher forces are required to induce expansion. This might give rise to higher pain, discomfort, and tension scores in older patients.

The strengths of this study were that the patients were homogeneous in age and gender distribution and were therefore representative of the most common age for RME treatment as well as the fact that questionnaires with documented good reliability and validity were used. In addition, selection bias was avoided because consecutive patients were invited and randomized into two groups in which the treatments were standardized and the only variable that differed was how the RME appliance was anchored.

This study has some limitations, however. The power analysis (not included) was based on skeletal effects of RME and not on pain measurements. A larger sample size might have been beneficial.

CONCLUSIONS

Although the hybrid RME generally resulted in lower pain and discomfort scores, no statistically significant differences were found between the groups.

Age was positively correlated with overall pain and discomfort.

Both types of appliances were generally well tolerated by the patients the first week in treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr Björn Ludwig, Department of Orthodontics, University of Homburg, Saar, Germany; Private Practice of Orthodontics in Traben-Trabach, Germany, for his support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fields HW, Proffit WR. Treatment in preadolescent children (section V) In: Proffit WR, editor. Contemporary Orthodontics 5th ed. St Louis, Mo: CV Mosby;; 2013. pp. 476–480. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lagravere MO, Major PW, Flores-Mir C. Long-term skeletal changes with rapid maxillary expansion: a systematic review. Angle Orthod. 2005;75:1046–1052. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2005)75[1046:LSCWRM]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bazargani F, Feldmann I, Bondemark L. Three-dimensional analysis of effects of rapid maxillary expansion on facial sutures and bones. Angle Orthod. 2013;83:1074–1082. doi: 10.2319/020413-103.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansen L, Tausche E, Hietschold V, Hotan T, Lagravere M, Harzer W. Skeletally-anchored rapid maxillary expansion using the Dresden Distractor. J Orofac Orthop. 2007;68:148–158. doi: 10.1007/s00056-007-0643-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mosleh MI, Kaddah MA, Abd ElSayed FA, ElSayed HS. Comparison of transverse changes during maxillary expansion with 4-point bone-borne and tooth-borne maxillary expanders. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2015;148:599–607. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2015.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lagravere MO, Gamble J, Major PW, Heo G. Transverse dental changes after tooth-borne and bone-borne maxillary expansion. Int Orthod. 2013;11:21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ortho.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheurer PA, Firestone AR, Burgin WB. Perception of pain as a result of orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. Eur J Orthod. 1996;18:349–357. doi: 10.1093/ejo/18.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Firestone AR, Scheurer PA, Burgin WB. Patients' anticipation of pain and pain-related side effects, and their perception of pain as a result of orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. Eur J Orthod. 1999;21:387–396. doi: 10.1093/ejo/21.4.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdelrahman RS, Al-Nimri KS, Al Maaitah EF. Pain experience during initial alignment with three types of nickel–titanium archwires: a prospective clinical trial. Angle Orthod. 2015;85:1021–1026. doi: 10.2319/071614-498.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halicioglu K, Kiki A, Yavuz I. Subjective symptoms of RME patients treated with three different screw activation protocols: a randomized clinical trial. Aust Orthod J. 2012;28:225–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Needleman HL, Hoang CD, Allred E, Hertzberg J, Berde C. Reports of pain by children undergoing rapid palatal expansion. Pediatr Dent. 2000;22:221–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gecgelen M, Aksoy A, Kirdemir P, et al. Evaluation of stress and pain during rapid maxillary expansion treatments. J Oral Rehabil. 2012;39:767–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2012.02330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baldini A, Nota A, Santariello C, Assi V, Ballanti F, Cozza P. Influence of activation protocol on perceived pain during rapid maxillary expansion. Angle Orthod. 2015;85:1015–1020. doi: 10.2319/112114-833.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganzer N, Feldmann I, Bondemark L. Pain and discomfort following insertion of miniscrews and premolar extractions: a randomized controlled trial. Angle Orthod. 2016;86:891–899. doi: 10.2319/123115-899.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldmann I, List T, Feldmann H, Bondemark L. Pain intensity and discomfort following surgical placement of orthodontic anchoring units and premolar extraction: a randomized controlled trial. Angle Orthod. 2007;77:578–585. doi: 10.2319/062506-257.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feldmann I, List T, John MT, Bondemark L. Reliability of a questionnaire assessing experiences from adolescents in orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod. 2007;77:311–317. doi: 10.2319/0003-3219(2007)077[0311:ROAQAE]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stegenga B, de Bont LG, de Leeuw R, Boering G. Assessment of mandibular function impairment associated with temporomandibular joint osteoarthrosis and internal derangement. J Orofacial Pain. 1993;7:183–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bergius M, Kiliaridis S, Berggren U. Pain in orthodontics. J Orofac Orthop/Fortschr Kieferorthop. 2000;61:125–137. doi: 10.1007/BF01300354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kvam E, Gjerdet NR, Bondevik O. Traumatic ulcers and pain during orthodontic treatment. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1987;15:104–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1987.tb00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Habersack K, Karoglan A, Sommer B, Benner KU. High-resolution multislice computerized tomography with multiplanar and 3-dimensional reformation imaging in rapid palatal expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;131:776–781. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]