Abstract

In this article, we provide definitional clarity for the construct of social withdrawal as it was originally construed, and review the original theoretical and conceptual bases that led to the first research program dedicated to the developmental study of social withdrawal (the Waterloo Longitudinal Project). We also describe correlates (e.g., social and social-cognitive incompetence), precursors (e.g., dispositional characteristics, parenting, insecure attachment), and consequences (e.g., peer rejection and victimization, negative self-regard, anxiety) of social withdrawal, and discuss how the study of this type of withdrawal led to a novel intervention that targets risk factors that predict social withdrawal and its negative consequences.

Keywords: social withdrawal, intervention, internalizing problems

During the past several decades, the study of social withdrawal in childhood has followed a research trajectory that can best be described as voluminous. Yet the construct represents somewhat of a conundrum. What began in the 1980s as a study of children’s behavioral displays of solitude in the company of peers has in recent years turned almost exclusively to a study of withdrawal subtypes defined by putative underlying motivations for spending time alone (Coplan et al., 2013). However, behavior is rarely considered in this recent work and evidence that these motivations are associated with or predict solitary behavior is scant. Thus, in this essay, we provide definitional clarity for the construct of social withdrawal as it was originally construed, and review the original theoretical and conceptual bases that led to the first research program dedicated to the developmental study of this type of withdrawal. We also describe correlates, precursors, and consequences of social withdrawal, and discuss how the study of this type of withdrawal led to the development of a novel intervention that targets risk factors that predict social withdrawal and its negative consequences.

Defining and Measuring Social Withdrawal

What Social Withdrawal Is

The first programmatic developmental study of social withdrawal, the Waterloo Longitudinal Project (WLP), began in the 1980s. When the WLP was initiated, social withdrawal was defined as the consistent (across situations and over time) display of solitary behavior in the company of familiar peers (Rubin, 1982a). Furthermore, a distinction was made between isolation from the peer group (social withdrawal) and isolation by the peer group. The latter referred to rejection, a construct central to research on peer relations. But unlike the study of sociometric rejection, the WLP began by examining whether children observed to display socially withdrawn behavior were more likely than their more sociable peers to have their social overtures ignored or rejected by their social “targets” or schoolmates.

What Social Withdrawal Is Not—Part 1

The WLP focused on the expression of solitude among familiar peers. In this case, social withdrawal must be contrasted with behavioral inhibition, or the inborn bias to respond to unfamiliar events, objects, or challenging social situations with anxiety or fearful behavioral reactions (Kagan et al., 1984). This is not to suggest that social withdrawal and behavioral inhibition are conceptually and empirically unrelated; however, they are not one and the same.

What Social Withdrawal Is Not—Part 2

Recently, researchers have referred to motivations that purportedly underlie reasons why youth spend time alone as social withdrawal subtypes. Yet this research is far removed from examining different behavioral forms of social withdrawal. For example, children may observe their peers from afar or spend solitary moments exploring or creating with objects (Rubin, 1982b). These varying behavioral forms of social withdrawal should not be equated with specific motivations for social withdrawal unless there are empirical reasons for so doing.

Shyness has been construed as a conflict between motivations to approach and avoid others. In early childhood, shyness is associated with fears of unfamiliar others; thereafter, shyness purportedly reflects self-conscious fears of negative evaluation by unfamiliar and familiar others (Schmidt & Buss, 2010). The early form of shyness has been equated with the construct of behavioral inhibition (Henderson et al. 2018); the latter maps onto the diagnostic category of social anxiety.

A second motivation thought to underlie social withdrawal is unsociability or the nonfearful preference for solitude. Other individuals are motivated to avoid social company. Shyness has been consistently associated with one behavioral form of social withdrawal—reticence, or observing others from afar (Coplan et al., 2013). Yet most of the research on reticence has involved observing preschoolers in a lab setting with unfamiliar agemates (Rubin et al., 2002). In studies of older children, shyness has been associated not only with reticence but with all forms of social withdrawal, as observed in the company of schoolmates (Asendorpf & van Aken, 1994; Coplan et al., 2013). Few studies suggest that either unsociability or avoidance motivations are associated with or predict observed displays of any behavioral manifestations of social withdrawal with familiar or unfamiliar peers (Spangler & Gazelle, 2009). Therefore, we advise researchers not to equate social withdrawal motivations with behavioral displays of withdrawal, either generally or in its different forms, until longitudinal work that allows for the examination of the transactional relations among withdrawal motivations, observed social withdrawal, and peer rejection is completed.

WLP Methods to Study Social Withdrawal

The WLP began as a study of observed social withdrawal in the company of familiar schoolmates. Researchers developed a taxonomy that allowed them to examine various types of observed solitude, as well as the extent to which children initiated interactions with peers, had their initiations accepted or rejected, received social bids from peers, and accepted or rejected peer initiations (Rubin, 1982b). Thus, the taxonomy allowed the examination not only of social withdrawal but also of social competence, or the ability to have one’s social initiations accepted by peers (Rubin & Krasnor, 1986). Children were observed during free play in preschool, kindergarten, and in second and fourth grades (Rubin et al., 1991).

Typically, in later elementary and middle school, opportunities to observe children engaging in free play in schools diminish. Consequently, almost all research on social withdrawal in elementary and middle school uses familiar schoolmates’ nominations or teachers’ ratings of social withdrawal. In the WLP, when the children were in the second, fourth, and fifth grades, researchers developed a peer nomination measure to assess social withdrawal from the peer group and isolation by the peer group (Rubin & Mills, 1988). This allowed them to distinguish peer-assessed social withdrawal from peer dislike.

Why Study Social Withdrawal?

Ironically, much of the original developmental research on social withdrawal derived from theory and research pertaining to the significance of social exchange for typical growth and development. Chapters in Carmichael’s Manual of Child Psychology (Mussen, 1970) served as a starting point; these chapters, by Piaget, Flavell, Hoffman, and Hartup, reviewed theory and research suggesting that differences of opinion experienced when peers interact with each other may result in acquisition of social knowledge. In turn, these interactions and the consequential understandings of the social world were thought to lay the foundation for the development of social cognition, competent social interactions, and adaptive peer relationships. From these chapters and earlier opinions about the developmental significance of peer interactions and relationships for psychological well-being (Sullivan, 1953), a zeitgeist devoted to the study of childhood peer experiences emerged.

The WLP was kick-started by a contrarian premise: If peer interaction is a significant force in the development of adaptive social cognitions, interactions, and relationships, children who do not interact with peers for whatever reason may be at risk for later maladaptation. A second basis for the WLP came from the perspectives of clinical psychologists who surmised that withdrawal was a behavioral reflection of psychological overcontrol. Despite the actuarial clustering of social withdrawal with indices of anxiety, depression, and negative self-regard (Achenbach, 1966), this clinical literature was fraught with methodological and conceptual problems. For example, in the few longitudinal studies done, social withdrawal did not predict negative outcomes; however, the so-called outcomes most often assessed were externalizing disorders (e.g., Janes et al., 1979). Thus, in the WLP, among the primary outcomes were indices of internalizing symptoms.

Correlates, Precursors, and Consequences of Social Withdrawal

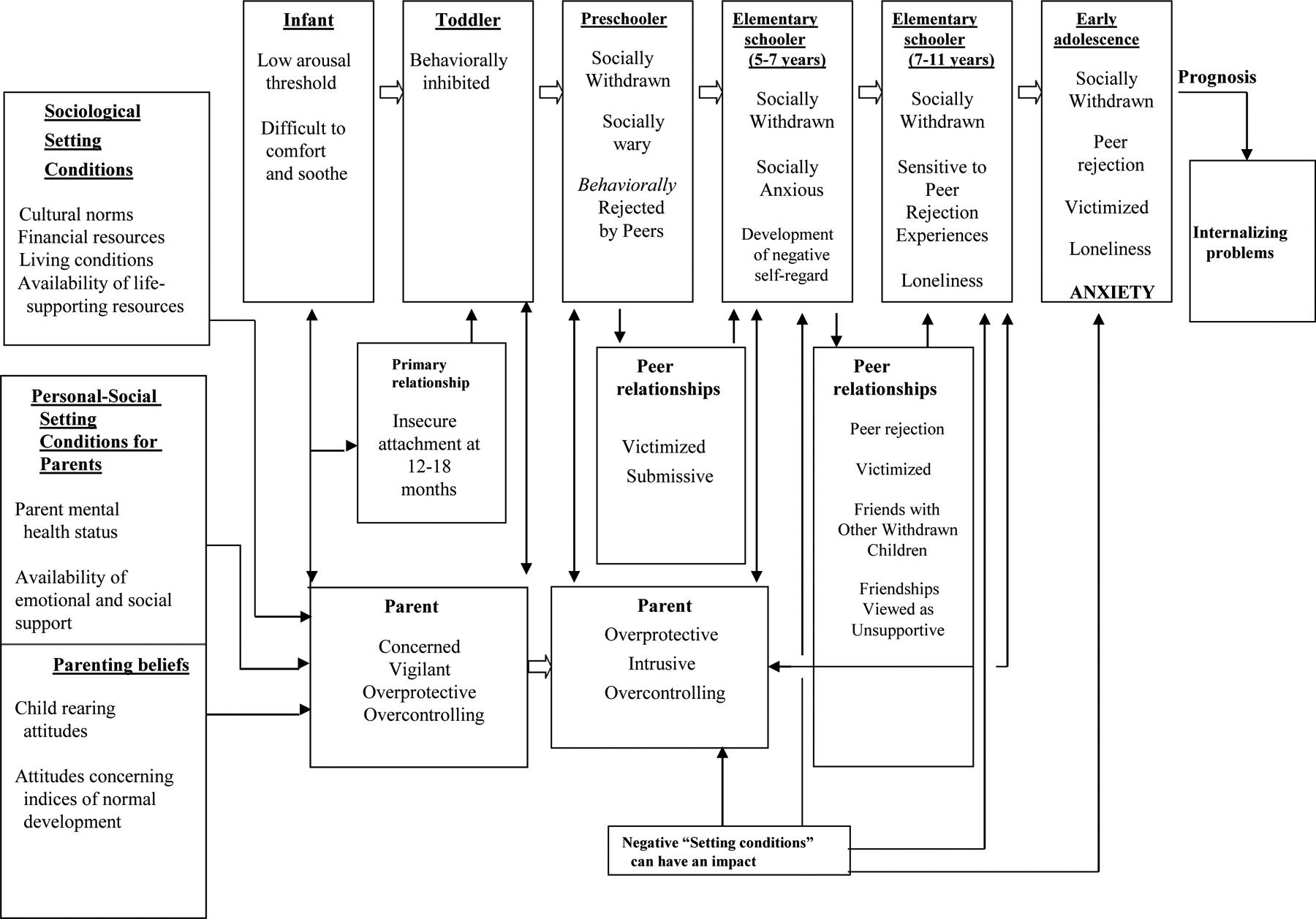

From the outset, the WLP was guided by a conceptual model that considered those constructs thought to influence the development, concomitants, and consequences of social withdrawal (Rubin & Lollis, 1988). In this article, we include an updated version of the model to guide discussion of the relevant literature on this type of withdrawal (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pathways to Social Withdrawal

Peer Interaction, Rejection, and the Self-System

Over the course of the WLP (1980–1995), we discovered that observed and peer-assessed social withdrawal was relatively stable. When extreme groups of socially withdrawn children were identified across any two-year period, from ages 5 to 11 years, approximately two-thirds of socially withdrawn children maintained their status as socially withdrawn (Rubin et al, 1991). Observed and peer-assessed social withdrawal was negatively associated with various indices of social-cognitive development, including perspective taking and interpersonal problem solving (Rubin & Krasnor, 1986). Moreover, when observed attempting to gain compliance from familiar peers, socially withdrawn children were more likely than their sociable counterparts to make low-cost requests (e.g., seeking peer attention rather than attempting to access desirable objects) and to be rebuffed by peers. Noncompliance to the observed requests of socially withdrawn children increased from early to middle childhood (Stewart & Rubin, 1995).

These latter findings were important for two reasons. First, the experience of failure in response to social initiatives suggested that socially withdrawn children do experience real-life rejection. Second, experiencing peer noncompliance carried with it negative emotional and cognitive burdens. For example, socially withdrawn children, unlike typical children, interpreted their social failures as resulting from internal, stable causes, contributing to a negative feedback loop whereby the initially fearful, socially withdrawn child comes to believe that social failure is dispositionally based, and this belief is reinforced by the experience of increasing interpersonal failure over time (Rubin & Krasnor, 1986).

Consistent with these negative attributions was the finding that social withdrawal from age 7 onward was negatively associated with self-perceptions of social skills and social relationships. With age, social withdrawal was increasingly accompanied by anxiety, loneliness, and depression, as well as by sociometric rejection (Rubin et al., 1991). These findings, especially those pertaining to the contemporaneous correlates of peer-assessed social withdrawal, have been replicated and extended in many studies (e.g., Ladd, 2006).

Friendship and Social Withdrawal

Despite difficulties with the peer group, socially withdrawn youth are as likely as nonwithdrawn youth to have best friendships that are stable over time (Ladd et al., 2011). However, their friendships are of lower quality, and tend to be formed with similarly withdrawn and victimized peers. Given the importance of reciprocity in children’s friendships, friends of socially withdrawn youth rate their relationships as less fun and helpful than do friends of typical youth (Rubin et al., 2006; Schneider, 1999). However, socially withdrawn youth do appear to benefit from friendship: Peer-assessed social withdrawal is negatively associated with loneliness only for those youth with mutual best friends (Markovic & Bowker, 2017).

Parenting and Parent-Child Relationships

In early studies, mothers of socially withdrawn preschoolers were more likely than mothers of typical children to suggest using high control strategies (directives) in reaction to hypothetical scenarios in which their children demonstrated social withdrawal among familiar peers. These mothers also attributed the consistent display of their children’s social withdrawal to dispositional sources, and expressed more guilt than mothers of typical children about their children’s displays of social withdrawal (Mills & Rubin, 1990). Also, relative to mothers of typical children, mothers of socially withdrawn children directed more statements of behavioral and psychological control to their children (Mills & Rubin, 1998). In this regard, maternal overcontrol encompassed not only restrictions on their child’s behavior, but also manifestations of anxiety and concern that conveyed a lack of confidence in the child.

More recently, maternal behavioral control, criticism, negativity, and a relative lack of supportiveness have been consistently associated with and predictive of social withdrawal in preschool- to elementary-school-aged children. Furthermore, in addition to parental behavior, an insecure parent-child attachment relationship has been associated with and predictive of increases in social withdrawal over time (Hastings et al., 2019).

Social Withdrawal as a Predictor of Maladaptation

The WLP revealed that social withdrawal at ages 5, 7, and 9 years predicted negative general self-worth, loneliness, and anxiety at 11 to 12 years. In the later elementary school years, withdrawal predicted negative self-perceptions of social competence, a lack of felt security within the family and the peer group, loneliness, and anxiety as youth made the transition from middle to high school (Rubin et al., 1995).

More recent studies have complemented and extended these findings, showing that social withdrawal predicts peer rejection, victimization, and exclusion (Ladd, 2006). Increases in children’s and adolescents’ social withdrawal can be predicted by rejection and exclusion, being sensitive to the prospect of being rejected, and having a socially withdrawn best friend (Gazelle & Faldowski, 2019; London et al., 2007; Oh et al., 2008). Perhaps most significantly, peer-assessed social withdrawal in childhood predicts symptoms of anxiety during childhood and adolescence, especially for those withdrawn children experiencing rejection (Gazelle & Ladd, 2003).

Culture and Social Withdrawal

Culture has been defined as “the set of attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors shared by a group of people, communicated from one generation to the next” (Matsumoto, 1997, p. 5). The form behaviors take may appear identical from one culture to another, yet the meaning attributed to any given social behavior is in large part a function of the ecological niche in which it is exhibited. Moreover, any behavior that is viewed as culturally adaptive will lead to its encouragement by significant others (e.g., parents, peers); in contrast, behavior perceived as maladaptive will lead others to discourage its growth and development (Rubin et al., 2009).

Social withdrawal among familiar peers has been studied in many countries and cultures (see Chen & Liu, 2021, for a review). Drawing mainly from peer nomination data, in cultural contexts in which such individual characteristics as assertiveness, expressiveness, and competitiveness are valued and encouraged, social withdrawal is linked to rejection (Rubin et al., 2009). Although research in China in the early 1990s indicated that shy, wary children were accepted by peers, recent findings indicate that shyness among urban Chinese children is associated with rejection. However, in rural China and among youth who have moved from rural to urban settings, shyness is associated with peer acceptance. These findings suggest the importance of considering generational, historical change in how behaviors may be interpreted (Chen & Liu, 2021); however, significantly, these data from China pertain to peer-assessed shyness, not social withdrawal.

Researchers have not examined programmatically the development, concomitants, and consequences of social withdrawal for diverse racial and ethnic groups within North America. Furthermore, in the cross-cultural developmental work on social withdrawal, observational research is lacking. The primary sources of information on withdrawal across cultures are peers, teachers, and parents.

Connecting Behavioral Inhibition to Social Withdrawal: The Contributions of Emotion Regulation and Parenting

The conceptual model in Figure 1 suggests how the constructs of behavioral inhibition and social withdrawal are connected. However, research has not fully connected the dots. For example, toddlers’ behavioral inhibition in the face of unfamiliar objects and adults frequently predicts reticent behavior among unfamiliar preschool-age peers. This relation is strengthened when a behaviorally inhibited toddler has low baseline respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA, indicating an inability to regulate levels of arousal; Buss & Qu, 2018). Furthermore, inhibited toddlers who experience maternal overprotection are more likely to be reticent with unfamiliar peers at age 4 (Rubin et al., 2002). Also, stable behavioral inhibition is associated not only with stable overprotective, highly controlling parenting (Hane et al., 2008), but also with parental anxiety (e.g., Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2007). The links among behavioral inhibition, emotion dysregulation, and parental overcontrol have been replicated in studies that have examined the longitudinal association between toddlers’ behavioral inhibition and preschoolers’ social withdrawal in unfamiliar situations (Hastings et al., 2014). Also, stable behavioral inhibition and reticence are strong risk factors for the development of anxiety in later childhood and adolescence, especially when biopsychosocial and parenting factors are considered (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009).

However, one missing link in the conceptual model is the connection between observed behavioral inhibition in the laboratory and observed social withdrawal among familiar peers in natural settings. Virtually no published research exists in which lab-based assessments of behavioral inhibition at 2 or 4 years predict observed school-based social withdrawal at 4 years and beyond. Although behavioral inhibition and its lab-assessed concomitants in early childhood may predict negative social and emotional outcomes in adolescence, surely peer interactions and relationships in natural settings must matter as well. Moreover, we know that parent-child relationships and parental behavior throughout the childhood years can influence trajectories of increasing social withdrawal and negative outcomes for withdrawn youth (Hastings et al., 2019).

Partial support for the association between behavioral inhibition and social withdrawal (or the lack thereof) comes from a few investigations. For example, in one study, behaviorally inhibited preschoolers were observed to engage in fewer positive peer interactions and to display more frequent fearful affect with classroom peers than were less inhibited children (Tarullo et al., 2011). In another study, preschoolers’ behavioral inhibition negatively predicted observed socially competent and prosocial behavior with familiar peers at 8 years (Bohlin et al., 2005). In yet another study, when behaviorally inhibited preschoolers were physiologically dysregulated (i.e., had lower RSA) and had mothers who were overprotective, they demonstrated poor social skills among familiar peers (as reported by teachers) five years later (Hastings et al., 2014). Taken together, these studies support a link between behavioral inhibition, as assessed among unfamiliar peers, and the display of incompetent social behavior among familiar schoolmates. However, few studies have tied lab-assessed behavioral inhibition to observed social withdrawal among familiar peers. As argued earlier, the peer rejection, victimization, and unsupportive friendships associated with social withdrawal augment the development of negative self-appraisals, rejection sensitivity, loneliness, and anxiety over the course of childhood and early adolescence.

Prospects: Reducing Behavioral Inhibition and Increasing Social Engagement

The empirical research we have described has helped identify targets for early intervention. Specifically, studies on behavioral inhibition and social withdrawal suggest that intervention must target the high-risk child, parenting, and peer relations to interrupt negative developmental processes. To this end, we developed the Turtle Program, a multimodal early intervention program for preschoolers.

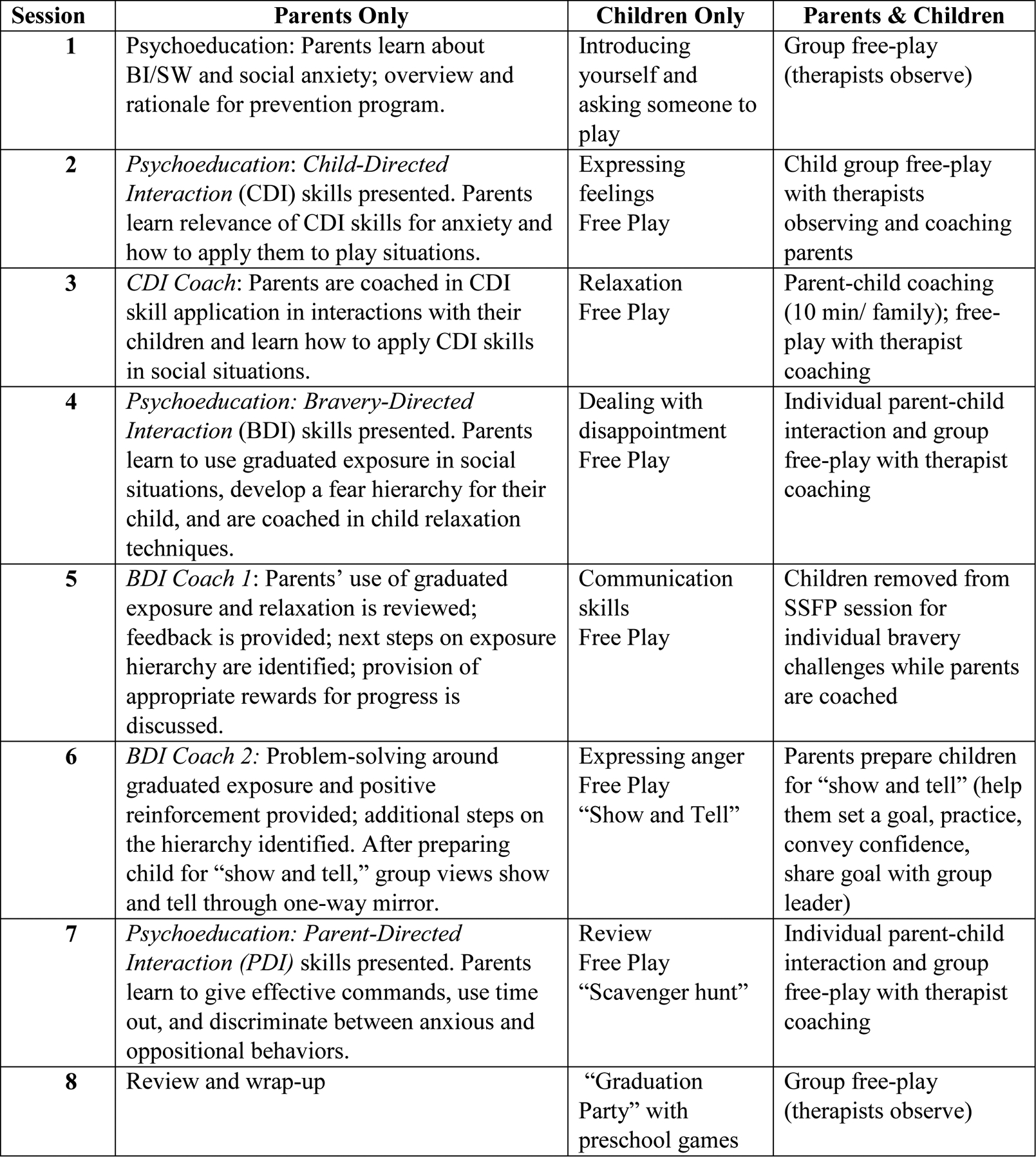

The Turtle Program enrolls preschoolers who have scored within the top 15 percent on the reliable and valid parent-rated Behavioral Inhibition Questionnaire (Bishop et al., 2003). The program is a comprehensive early intervention for extremely inhibited 3- to 5-year-olds that features eight weekly concurrent parent and child group sessions. The development of the program was influenced by Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT; Pincus et al., 2005) and the Social Skills Facilitated Play intervention (SSFP; Coplan et al., 2010). PCIT sessions include psychoeducation and didactic instruction (teach sessions) as well as in-person coaching of parents as they practice relevant skills (coach sessions). A unique feature of the intervention is that the SSFP sessions allow for in-person coaching of parents when their child is with peers. In group sessions with four to seven initially unfamiliar peers, SSFP group leaders teach social and emotion regulation skills (e.g., introducing oneself, making friends, expressing emotions, mindfulness, decreasing social anxiety) using modeling, reinforcement, and guided participation to scaffold children’s interactions with peers. Thus, in line with the abovementioned conceptual model, the Turtle intervention simultaneously addresses children’s behavioral inhibition and social withdrawal (as peers become increasingly familiar), and parent-child and peer interactions to influence the developmental course of anxiety in this high-risk group. Turtle Program sessions are outlined in Figure 2 (see Danko et al., 2018, for a full description).

Figure 2.

The Turtle Program*

*Note. For a detailed description, see Danko et al. (2018)

An initial evaluation of the program involved a randomized controlled trial comparing the Turtle Program to a control condition of families on a waiting list (Chronis-Tuscano et al, 2015). Outcomes have been assessed using a variety of methods, including diagnostic interviews, parent ratings, observed parent-child interactions in the laboratory, teacher ratings of each child in the classroom context, and observations of each child during free play with their familiar schoolmates. The Turtle Program had significant beneficial effects on parent-reported anxiety symptoms and behavioral inhibition in children, and on observed maternal warm, engaged parenting, and decreased observed parental negative control. Teacher ratings revealed decreases in children’s anxiety symptoms. Significantly, the Turtle program increased observed group play and social initiations directed toward familiar peers in the preschool setting (Barstead et al., 2018).

In an ongoing followup study, we have assessed the same measures as those used in the initial project, and added a range of outcomes and potential mediators and moderators, including parent anxiety disorders, parents’ and children’s emotion reactivity and regulation (RSA), and observations of social withdrawal among familiar peers. Our main goal is to evaluate the relative effects of the Turtle Program compared with Cool Little Kids (Rapee et al., 2005), a six-session intervention for parents of young behaviorally inhibited children, and to identify who might benefit most from receiving the more intensive Turtle Program in terms of optimal clinical and developmental outcomes. Another goal is to understand how these treatments work to improve children’s anxiety symptoms.

We are just beginning to examine whether treatment outcomes vary between the two interventions. Data analyses will allow us to look at how the treatments work, how parents’ and children’s reactivity and regulation (assessed via RSA) mediate or moderate treatment effects, and the extent to which these treatments generalize differentially to the school setting (e.g., decreases in social withdrawal). We already know that we had to begin with a developmentally strong, conceptual model supported by empirical data to develop a successful treatment program.

Conclusion

In this article, we have described several decades of theoretically driven research on the development, manifestation, and motivations of social withdrawal, culminating in the translation of these findings with the development and evaluation of an intervention program. We hope this can serve as a model for theory-driven developmental and multidisciplinary science to enhance the understanding and adaptive outcomes of this high-risk group.

One remaining gap in the literature involves the study of social withdrawal among older adolescents and young adults. Studying these age groups would involve new methods, such as using smartphones and other web-based assessments to assess social withdrawal in natural settings. Additionally, developmentally informed outcomes of adolescent and young adult social withdrawal, such as occupational choices, employment status, and the status of social relationships (including romantic relationships) merit attention. We hope these suggestions result in a new wave of research pertaining to the correlates and consequences of varying forms of social withdrawal as the field moves forward.

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this article was supported by the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health (MH103253-02).

References

- Achenbach TM (1966). The classification of children’s psychiatric symptoms: A factor-analytic study. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 80(7), 1–37. 10.1037/h0093906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asendorpf JB, & van Aken MAG (1994). Traits and relationship status: Stranger versus peer group inhibition and test intelligence versus peer group competence as early predictors of later self-esteem. Child Development, 65(6), 1786–1798. 10.2307/1131294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barstead MG, Danko CM, O’Brien KO, Coplan RJ, Chronis-Tuscano A, & Rubin KH (2018). Generalization of an early intervention for inhibited preschoolers to the classroom setting. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(9), 2943–2953. 10.1007/s10826-018-1142-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop G, Spence SH, & McDonald C (2003). Can parents and teachers provide a reliable and valid report of behavioral inhibition? Child Development, 74(6), 1899–1917. 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00645.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlin G, Hagekull B, & Andersson K (2005). Behavioral inhibition as a precursor of peer social competence in early school age: The interplay with attachment and nonparental care. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 51(1), 1–19. 10.1353/mpq.2005.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buss K & Qu J (2018). Psychobiological processes in the development of behavioral inhibition. In Perez-Edgar K & Fox NA (Eds.), Behavioral inhibition during childhood and adolescence (pp. 91–112). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, & Liu M (2021). Culture, social withdrawal, and development. In Coplan RJ, Bowker JC, & Nelson LJ (Eds.), The handbook of solitude: Psychological perspectives on social isolation, social withdrawal, and being alone (2nd ed.). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Degnan KA, Pine DS, Perez-Edgar K, Henderson HA, Diaz Y, Raggi VL, & Fox NA (2009). Stable early maternal report of behavioral inhibition predicts lifetime social anxiety disorder in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(9), 928–935. 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181ae09df [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Rubin KH, O’Brien KA, Coplan RJ, Thomas SR, Dougherty LR, Cheah CSL, Watts K, Heverly-Fitt S, Huggins SL, Menzer M, Begle AS, & Wimsatt M (2015). Preliminary evaluation of a multi-modal early intervention program for behaviorally inhibited preschoolers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(3), 534–540. 10.1037/a0039043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan R, Rose-Krasnor L, Weeks M, Kingsbury A, Kingsbury M, & Bullock A (2013). Alone is a crowd: Social motivations, social withdrawal, and socioemotional functioning in later childhood. Developmental Psychology, 49(5), 861–875. 10.1037/a0028861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Schneider BH, Matheson A, & Graham A (2010). ‘Play skills’ for shy children: Development of a social skills facilitated play early intervention program for extremely inhibited preschoolers. Infant and Child Development 19(3), 223–237. 10.1002/icd.668 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Danko CM, O’Brien KA, Rubin KH, & Chronis-Tuscano A (2018). The Turtle Program: PCIT for young children displaying behavioral inhibition. In Niec LN (Ed.), Handbook of parent-child interaction therapy: Innovations and applications for research and practice. (pp. 85–98). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Gazelle H, & Faldowski RA (2019). Multiple trajectories in anxious solitary youths: The middle school transition as a turning point in development. Journal of Abnormal Child psychology, 47(7), 1135–1152. 10.1007/s10802-019-00523-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazelle H, & Ladd GW (2003). Anxious solitude and peer exclusion: A diathesis-stress model of internalizing trajectories in childhood. Child Development, 74(1), 257–278. 10.1111/1467-8624.00534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hane AA, Cheah CSL, Rubin KH, & Fox NA (2008). The role of maternal behavior in the relation between shyness and social withdrawal in early childhood and social withdrawal in middle childhood. Social Development, 17(4), 795–811. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00481.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PD, Kahle S, & Nuselovici JM (2014). How well socially wary preschoolers fare over time depends on their parasympathetic regulation and socialization. Child Development, 85(4), 1586–1600. 10.1111/cdev.12228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PD, Rubin KH, Smith KA, & Wagner N (2019). Parents of socially withdrawn children. In Bornstein M (Ed.), Handbook of parenting. (3rd ed., pp. 467–495). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson HA, Green ES, & Wick BL (2018). The social world of behaviorally inhibited children: A transactional account. In Perez-Edgar K & Fox NA (Eds.), Behavioral inhibition during childhood and adolescence. (pp. 135–156). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Biederman J, Henin A, Faraone SV, Davis S, Harrington K, & Rosenbaum JF (2007). Behavioral inhibition in preschool children at risk is a specific predictor of middle childhood social anxiety: A five-year follow-up. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 28(3), 225–233. 10.1097/01.DBP.0000268559.34463.d0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janes CL, Hesselbrock VM, Myers DG, & Penniman JH (1979). Problem boys in young adulthood: Teachers’ ratings and twelve-year follow-up. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 8(4), 453–472. 10.1007/BF02088662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Reznick J, Clarke C, Snidman N, & Garcia-Coll C (1984). Behavioral inhibition to the unfamiliar. Child Development, 55(6), 2212–2225. 10.2307/1129793 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW (2006). Peer rejection, aggressive or withdrawn behavior, and psychological maladjustment from ages 5 to 12: An examination of four predictive models. Child Development, 77(4), 822–846. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00905.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Kochenderfer-Ladd B, Eggum N, Kochel K, & McConnell E (2011). Characterizing and comparing the friendships of anxious solitary and unsociable preadolescents. Child Development, 82(5), 1434–1453. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01632.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London B, Downey G, Bonica C, & Paltin I (2007). Social causes and consequences of rejection sensitivity in adolescents. Journal of Research in Adolescence, 17(3), 481–506. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00531.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Markovic A, & Bowker JC (2017). Friends also matter: Examining friendship adjustment indices as moderators of anxious-withdrawal and trajectories of change in psychological maladjustment. Developmental Psychology, 53(8), 1462–1473. 10.1037/dev0000343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto D (1997). Culture and modern life. Brooks/Cole. [Google Scholar]

- Mills RSL, & Rubin KH (1990). Parental beliefs about problematic social behaviors in early childhood. Child Development, 61(1), 138–151. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02767.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mills RSL, & Rubin KH (1998). Are behavioral control and psychological control both differentially associated with childhood aggression and social withdrawal? Canadian Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 30(2), 132–136. 10.1037/h0085803 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mussen PH (Ed.) (1970). Carmichael’s manual of child psychology. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Oh W, Rubin KH, Bowker JC, Booth-LaForce C, Rose-Krasnor L, & Laursen B (2008). Trajectories of social withdrawal from middle childhood to early adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(4), 553–566. 10.1007/s10802-007-9199-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pincus DB, Eyberg SM, & Choate ML (2005). Adapting parent-child interaction therapy for young children with separation anxiety disorder. Education Treatment of Children, 28(2), 163–181. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42899839 [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM, Kennedy S, Ingram M, Edwards S, & Sweeney L (2005). Prevention and early intervention of anxiety disorders in inhibited preschool children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 488–497. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH (1982a). Social and social-cognitive developmental characteristics of young isolate, normal and sociable children. In Rubin KH & Ross HS (Eds.), Peer relationships and social skills in childhood (pp. 353–374). Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH (1982b). Non-social play in preschoolers: Necessarily evil? Child Development, 53(3), 651–657. 10.2307/1129376 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Burgess KB, & Hastings PD (2002). Stability and social-behavioral consequences of toddlers’ inhibited temperament and parenting. Child Development, 73(2), 483–495. 10.1111/1467-8624.00419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Cheah CSL & Menzer M (2009). Peer relationships. In Bornstein M (Ed.), Handbook of cross-cultural developmental science. (pp. 223–238). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Chen X, McDougall P, Bowker A, & McKinnon J (1995). The Waterloo Longitudinal Project: Predicting adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems from early and mid-childhood. Development and Psychopathology, 7(4), 751–764. 10.1017/S0954579400006829 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Hymel S, Mills RSL & Rose-Krasnor L (1991). Conceptualizing different pathways to and from social isolation in childhood. In Cicchetti D and Toth S (Eds.), The Rochester symposium on developmental psychopathology, Vol. 2, Internalizing and externalizing expressions of dysfunction, (pp. 91–122). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH & Krasnor LR (1986). Social-cognitive and social behavioral perspectives on problem solving. In Perlmutter M (Ed.), Cognitive perspectives on children’s social and behavioral development. The Minnesota symposia on child psychology (Vol. 18, pp. 1–68). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, & Lollis S (1988). Origins and consequences of social withdrawal. In Belsky J & Nezworski T (Eds.), Clinical implications of attachment (pp. 219–252). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, & Mills RSL (1988). The many faces of social isolation in childhood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(6), 916–924. 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Wojslawowicz JC, Burgess KB, Rose-Krasnor L, & Booth-LaForce CL (2006). The friendships of socially withdrawn and competent young adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34(2), 139–153. 10.1007/s10802-005-9017-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt LA, & Buss AH (2010). Understanding shyness: Four questions and four decades of research. In Rubin KH & Coplan RJ (Eds.), The development of shyness and social withdrawal (pp. 23–41). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider BH (1999). A multimethod exploration of the friendships of children considered social withdrawn by school peers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 27(2), 115–123. 10.1023/A:1021959430698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangler T, & Gazelle H (2009). Anxious solitude, unsociability, and peer exclusion in middle childhood: A multitrait-multimethod matrix. Social Development, 18(4), 833–856. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00517.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SL & Rubin KH (1995). The social problem solving skills of anxious-withdrawn children. Development and Psychopathology, 7(2), 323–336. 10.1017/S0954579400006532 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan HS (1953). The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Tarullo AR, Mliner S, & Gunnar MR (2011). Inhibition and exuberance in preschool classrooms: Associations with peer social experiences and changes in cortisol across the preschool year. Developmental Psychology, 47(5), 1374–1388. 10.1037/a0024093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]