Abstract

Objective

To study 30-day readmission (30-DR) rate and predictors for readmission among elderly patients with delirium.

Methods

This was a retrospective observational cohort study of patients aged ≥65 years with discharge diagnosis of delirium identified from the Nationwide Readmission Database using common International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, and Clinical Modification codes linked to delirium diagnosis. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed adjusting for stratified cluster design to identify patient/system-specific factors associated with 30-DR.

Results

Overall, the 30-DR rate was 17% (7,140 of 42,655 weighted index admissions). The common causes of readmission were systemic diseases (43%), infections (27%), and neurologic diseases (18%). Compared with initial hospitalization, readmission costs were higher ($11,442 vs $10,350, p < 0.0001) with a longer length of stay (6.6 vs 6.1 days, p < 0.0001). Independent predictors of readmission included discharge against medical advice (odds ratio [OR] 1.8, p < 0.0034), length of stay (OR 1.3, p < 0.0001), and chronic systemic diseases (anemia, OR 2.4, p < 0.0001, chronic renal failure OR 1.4, p < 0.0001, congestive heart failure OR 1.3, p < 0.0001, lung disease OR 1.2, p < 0.0004, and liver disease OR 1.2, p < 0.03). Private insurance was associated with a lower risk of readmission (OR 0.78, p < 0.02).

Conclusions

The main predictors of readmission were chronic systemic diseases and discharge against medical advice. These data may help design directed clinical care pathways to optimize medical management and postdischarge care to reduce readmission rates.

Delirium, also referred to as acute confusional state, is a clinical syndrome characterized by acute transient changes in cognition and attention, often accompanied by disturbances of the sleep-wake cycle and psychomotor behavior. Acute encephalopathy and altered mental status are other terms used to describe the syndrome. Elderly patients are at a higher risk of delirium due to higher concomitant disease and medication burden, frequent hospitalization and procedures, and low functional reserve. The incidence of delirium in elderly patients ranges from 4% to 40% in the hospital setting, and it is associated with significant morbidity, increased mortality, longer hospital length of stay (LOS), cognitive worsening, and progressive functional decline leading to institutionalization.1–7

In-hospital patients with delirium have a higher risk of readmission.7 Readmissions are associated with higher resource utilization, cost of health care services, and poor patient outcomes.8 Approximately 20% of all Medicare discharges are readmitted within 30 days, estimated to cost $17 billion annually, almost one-fifth of all Medicare hospital payments.9–11 Thirty-day readmission rate (30-DRR) is an important metric for quality of care and clinical performance. For hospitals with high readmission rates, penalties are imposed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Understanding the causes and predictors of 30-DR may help reduce readmission rates and associated health care costs.12,13 Previous studies on readmission in delirium have focused on specific groups such as patients with cognitive impairment and stroke or following surgery; few have assessed delirium from all causes.5,6,14,15 We assessed 30-DRR and causes and predictors of readmissions in patients aged ≥65 years with all-cause delirium.

Methods

This was a retrospective observational study using the National Readmission Database (NRD) derived from Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP)'s for the year 2014. NRD is 1 of 7 publicly available databases in the HCUP sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.16 The database represents 49.1% of total US hospitalizations excluding rehabilitation and long-term acute care facilities from 21 states.16 We used NRD visit link (NVL) to identify index hospitalizations for delirium and to track readmissions following the index admission. NVL is a unique patient identifier number that provides verifiable information on hospital visits across the states for an individual patient. The index admissions were identified by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, and Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code for the primary discharge diagnosis. The following ICD-9 codes commonly linked to the diagnosis of delirium or encephalopathy were used to identify the patients: 293.1 (subacute delirium), 290.3 (senile dementia with delirium), 291.0 (alcohol withdrawal delirium), 348.3 (encephalopathy, not elsewhere classified), 290.41 (vascular dementia with delirium), 290.11 (presenile dementia with delirium), and 292.81 (drug-induced delirium). The readmission was defined as admission to a state hospital within 30 days of discharge following the index hospitalization for any cause. Readmission was identified by using the database variables: visit link NVL and the time variable NRD DaystoEvent. We used sampling weights (discharge weight) provided in the NRD database to generate the national readmission rate. Discharge weights for national appraisals are produced using the objective universe of community hospitals (barring rehabilitation and long-term acute care hospitals) in the United States.17

Patient Selection

The study cohort was derived from 106,052 patients admitted between January and November 2014 who had a primary discharge diagnosis of delirium (figure 1). The patients admitted during the month of December were excluded as 30-day follow-up data to identify readmissions for these index admissions were not available in 2014 NRD data set. In addition, cases with age ≤65 years or who died after index admission were excluded. The study was exempt from Institutional Board Review as it only used publicly available deidentified data.

Figure 1. Study Design and Patient Selection Algorithm.

Data and Variables

The data on patient demographics, hospital characteristics such as number of beds and teaching status, socioeconomic factors including median household income category for patients' zip code and primary payer, comorbidities, LOS, admission day, and discharge disposition were collected from NRD. The comorbidities were identified by ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes listed in the diagnosis fields during the index admission. The modified Charlson-Deyo Comorbidity Index (CCI), an established measure to quantify the burden of comorbid conditions, was calculated; the scores range from 0 to 33, with the higher score indicating a greater burden of concomitant diseases.18 These comorbidities were likely present before the index admission and not directly related to the primary diagnosis or the main reason for admission. The HCUP's NRD contains data on total charges, which reflect the amount hospitals bill for services. The cost of inpatient care for a discharge is calculated by multiplying total charges from the discharge record by the all-payer inpatient cost/charge ratio provided by HCUP. The in-pateint cost/charge ratio is based on the hospital-specific all-payer inpatient cost/charge ratio or the group average all-payer inpatient cost/charge ratio.17

Outcomes

The outcomes were (1) 30-DRR, (2) causes for readmission, (3) LOS and cost during index admission and readmission, and (4) predictors of readmission.

Statistical Analyses

We used SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) for data analysis. Bivariate analyses were conducted followed by multivariate analysis. Readmission analyses were performed via multivariable logistic regression after adjusting for stratified cluster design of NRD and covariables including patient demographics, hospital-specific factors, socioeconomic variables, discharge disposition, and most prevalent comorbidities. We used a likelihood ratio test for computing the goodness of fit for a multivariable logistic model with a p value of <0.05. Four hundred six observations were deleted from the regression models due to missing values for the response or explanatory variables.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

All authors (H.L.L., S.D.P., and N.G.) complied with the ethical standards of the University of Miami. No patient consent was required. We confirm that we have read the journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines.

Data Availability

Data not published within this article are available in a public repository, NRD derived from HCUP's for the year 2014. We used NRD visit link (NVL) to identify index hospitalizations for delirium and to track readmissions following the index admission.

Results

Summary of the Study Population

There was a weighted N of 42,655 patients aged ≥65 years identified with discharge diagnosis of delirium from the 2014 NRD data set after applying exclusions for age, missing LOS, and discharge month of December (figure 1). The overall 30-DR rate was 16.7%, with a total of 7,140 patients readmitted during the 30-day postdischarge period included in the study. The median interval to readmission was 10 days.

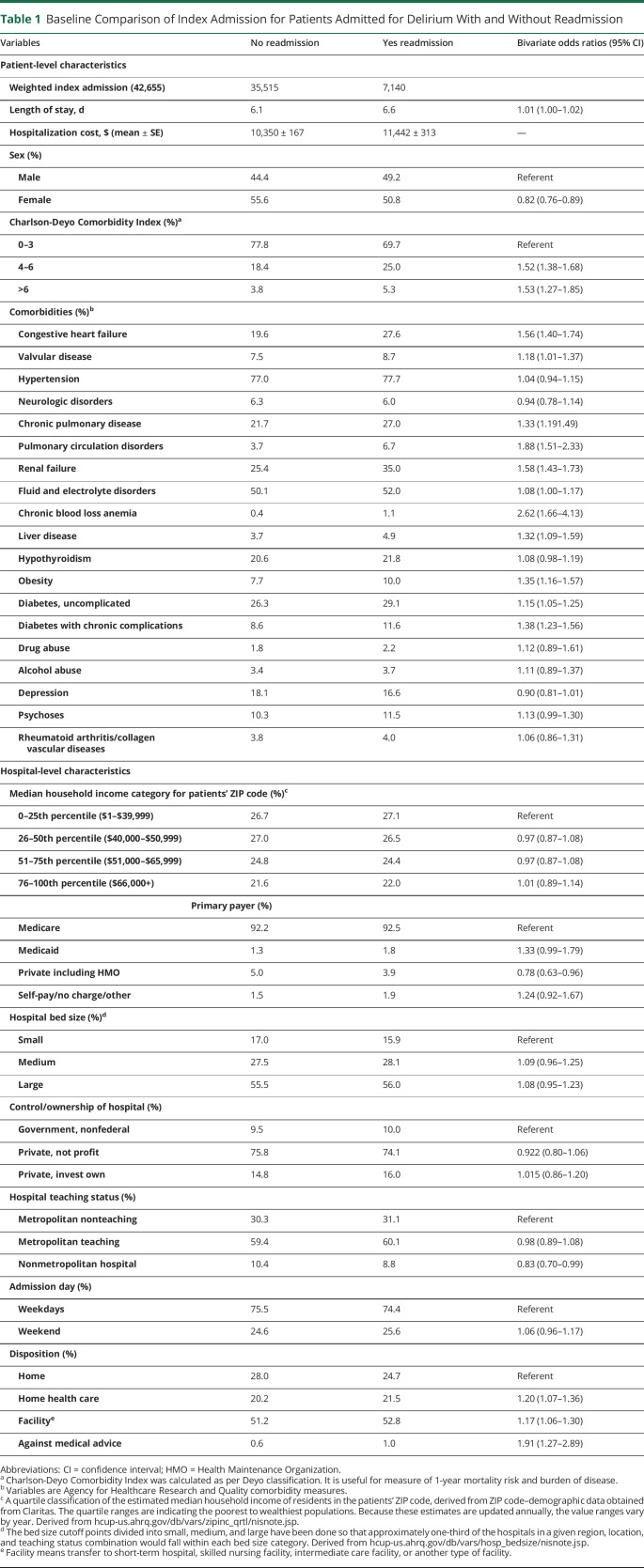

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of patients who were readmitted compared with patients not readmitted. Men were more likely than women to be readmitted. Patients with higher numbers of comorbidities (measured by the CCI) such as diabetes, obesity, anemia, renal, cardiac, and pulmonary disorders also had significantly higher readmission rate. There were no significant differences in hospital size or teaching status, weekday vs weekend admissions, or median household income. The readmitted patients were less likely to have private insurance, more likely to leave against medical advice (AMA), require home health services, or be discharged to a facility. Compared with initial (index) hospitalization, readmission had longer LOS (6.6 vs 6.1 days, p < 0.0006) and hospitalization cost ($11,442 vs $10,350, p < 0.0001).

Table 1.

Baseline Comparison of Index Admission for Patients Admitted for Delirium With and Without Readmission

Trends and Causes for Readmission

The trends of 30-DR showed that 38.4% of readmissions occurred within the first week and nearly two-thirds (62%) within the first 2 weeks. Of (unweighted) 3,281 readmitted patients, 98% (3,206 patients) were readmitted once, 2% (69 patients) readmitted twice, and 0.18% (6 patients) were readmitted 3 times or more.

Causes of Readmissions

The common causes of readmission were systemic diseases (43%), infections (27%), and neurologic diseases (18%); other causes are listed in table 2.

Table 2.

All Causes/Etiologies of Unplanned Readmission Within 30 Days of Discharge in Patients Aged ≥65 Years (N = 7,140) With a Primary Diagnosis of Delirium

Predictors of 30-DR

On multivariable analysis (table 3), the main predictors of 30-DR were anemia (odds ratio [OR] 2.4, p < 0.001), chronic systemic diseases (chronic renal failure OR 1.4, p < 0.001, congestive heart failure OR 1.3, p < 0.001, pulmonary disorders OR 1.2, p < 0.001, and diabetes OR 1.2, p = 0.006), discharge AMA (OR 1.8, p < 0.009), and LOS >6 days (OR 1.2, p < 0.0003) during index hospitalization. Private insurance (OR 0.78, p < 0.02) and female sex (OR 0.82, p < 0.001) were associated with a lower risk of readmission.

Table 3.

Multivariable Analysis for Predictors of Readmission Within 30 Days in Patients Discharged With a Primary Diagnosis of Delirium

Discussion

Our study shows that 30-DR is common in elderly patients with delirium and is mostly related to associated comorbidities. Delirium in elderly patients is associated with a significant health care burden given the negative health outcomes and substantial economic costs related to readmissions. This study helps in understanding the factors that may contribute to readmissions. The readmission rate in our study is comparable to previously reported rates in specific delirium population with preexisting dementia, stroke, or postsurgical patients.5,6,11,19 The 30-DRR for delirium in our study is, however, higher than the rates reported for other neurologic disorders, such as epilepsy (10.8%) and stroke (8%–12%, worse with hemorrhagic subtypes); this could partly be due to older age and associated higher medical disease burden in our cohort.6,20–22 The readmission rate in our cohort is similar to reported in elderly patients with systemic diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (18%–20%) and heart failure.11,23,24

The common causes of 30-DR in our cohort were chronic systemic diseases and infections. The systemic diseases including diabetes, chronic heart, liver, and renal diseases are common in elderly patients and often associated with risk factors for hospitalization such as polypharmacy, poor health reserve, and increased infection risk. Similarly, infection is a known trigger for de novo and recurrent delirium in elderly patients. Infection is also one of the common causes for readmission among elderly patient population.11,25 Elderly patients with multiple chronic comorbidities may be predisposed to geriatric or posthospital syndromes, a condition of vulnerability in elderly patients with a known greater risk of readmission.11,26 A significant proportion of patients in our study had neurologic causes for readmission, which is expected as several neurologic disorders (e.g., dementia and stroke) and the resultant deficits are known risk factors for delirium.6

The major predictors of readmission were anemia and other systemic diseases, consistent with previous reports where the presence and degree of anemia being independent predictors of higher readmission rates in elderly patients following emergency department visit for chronic heart and lung disease.15,27,28 Anemia is common and likely related to other systemic diseases in elderly patients. Chronic renal failure, another predictor of readmission in our study, is a well-known risk factor for readmission in older patients, especially in patients with a history of delirium or cognitive impairment.29 Similarly, as in our study, patients with diabetes are known to be at a higher risk of readmission.30 A longer index hospitalization LOS (>6 days) was an independent predictor of readmission. This can be explained by higher risk of secondary complications expected during prolonged hospital stay, which in turn may be related to higher comorbid disease burden requiring prolonged care and hospitalization in this patient population.

The difference in readmission rates based on insurance status likely reflects health care disparities due to differences in socioeconomic status and access to good medical care after discharge similar to reported in other diseases.31 The patients with private insurance generally belong to higher socioeconomic group and are expected to have better health care outcomes.32 The median household is a reflection of socioeconomic status however did not correlate with readmission suggesting role of other noneconomic factors. One possible explanation could be the availability of better social support system and postdischarge care. Similarly, AMA being a predictor for readmission could be related to patient-specific psychosocial factors. The factors associated with AMA discharge include socioeconomic status, family issues, psychiatric comorbidities, poor insight into medical condition, and dissatisfaction with health care, which may all affect follow-up care and increase the risk of readmission.33,34 A recent study showed a higher readmission rate among patients discharged AMA and also a higher rate of repeat AMA discharges following readmission, especially in patients with alcohol-related disorders.35 Another small study showed that less than a third of patients leaving AMA have a follow-up plan or medication prescriptions at the time of discharge.36

In our cohort, men were more likely to be readmitted; this could partly be explained by men being more susceptible to delirium and readmissions in general.37 There are mixed reports about sex differences in overall readmission risk; most studies on elderly patients with delirium reported no significant sex-based differences.11,25

The main strength of our study is a large cohort of inpatients with all-cause delirium in contrast to existing literature on inpatient delirium, which mostly included select patient groups with specific medical or surgical conditions. The NRD is the largest American longitudinal inpatient database, which has previously been used for studies on readmissions with other neurologic and systemic diseases. The study cohort is fairly representative of general elderly population, increasing generalizability of these observations. The data in our study were only collected for the year 2014. Although year-to-year variations in readmission are possible, our preliminary analysis of readmissions in 2013 (not reported here) produced similar results.

NRD database is, however, limited due to unique patient identifiers, which do not capture readmissions to hospitals in some states. We used ICD-9-CM codes for delirium to identify cases, which may not have captured all cases of delirium; in addition, cases may have been underrepresented due to physician coding errors. The data on factors with potential impact on readmission rate such as psychosocial elements, type/quality of postdischarge care, severity of systemic disease, and polypharmacy were not available. Like other database studies, our study is also subject to inherent weaknesses of retrospective and observational design, yielding associations rather than causation.

In conclusion, the 30-day readmission rate in elderly patients with delirium was similar to reported for other medical conditions though higher than other neurologic diseases. The majority of readmissions were secondary to chronic systemic diseases and infections. Chronic medical conditions were the main predictors of readmission. Based on these observations, we propose targeted strategies such as directed clinical care pathways during hospitalization for optimal management of chronic medical conditions to help reduce readmissions. In addition, postdischarge transitional care management of at-risk individuals with high comorbid disease burden and prolonged hospitalization should focus on chronic disease management that may include supervised medication administration and closer follow-up visit with primary care physicians.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

→ The 30-day readmission rates in elderly patients with delirium were slightly higher than common neurologic diseases such as epilepsy and stroke.

→ Readmissions were associated with higher costs and longer length of stay compared with the index admissions reflecting higher health care burden.

→ Readmissions in the majority of cases were due to systemic diseases and infections.

→ The main predictors of readmission were chronic systemic diseases including anemia, renal, heart, and liver disease, and discharge against medical advice.

→ There is need to optimize medical management during hospitalization and postdischarge care in this patient population to reduce readmission rate; implementing a clinical care pathway to standardize care may be helpful.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. Micheline McCarthy, Professor of Neurology, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, for reviewing the manuscript and providing valuable suggestions.

Appendix. Authors

Study Funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

References

- 1.Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, Inouye SK. Delirium in elderly adults: diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol 2009;5:210–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Douglas VC, Josephson SA. Altered mental status. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2011;17:967–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han JH, Eden S, Shintani A, et al. Delirium in older emergency department patients is an independent predictor of hospital length of stay. Acad Emerg Med 2011;18:451–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pendlebury ST, Lovett NG, Smith SC, et al. Observational, longitudinal study of delirium in consecutive unselected acute medical admissions: age-specific rates and associated factors, mortality and re-admission. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reynish EL, Hapca SM, De Souza N, Cvoro V, Donnan PT, Guthrie B. Epidemiology and outcomes of people with dementia, delirium, and unspecified cognitive impairment in the general hospital: prospective cohort study of 10,014 admissions. BMC Med 2017;15:140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vahidy FS, Bambhroliya AB, Meeks JR, et al. In-hospital outcomes and 30-day readmission rates among ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke patients with delirium. PLoS One 2019;14:e0225204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LaHue SC, Douglas VC, Kuo T, et al. Association between inpatient delirium and hospital readmission in patients >/=65 years of age: a retrospective cohort study. J Hosp Med 2019;14:201–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leslie DL, Inouye SK. The importance of delirium: economic and societal costs. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59(suppl 2):S241–S243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubin FH, Bellon J, Bilderback A, Urda K, Inouye SK. Effect of the hospital elder life program on risk of 30-day readmission. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66:145–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Hospital readmission performance and patterns of readmission: retrospective cohort study of Medicare admissions. BMJ 2013;347:f6571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1418–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:520–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, et al. Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA 2011;306:1688–1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kennedy M, Enander RA, Tadiri SP, Wolfe RE, Shapiro NI, Marcantonio ER. Delirium risk prediction, healthcare use and mortality of elderly adults in the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:462–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma IC, Chen KC, Chen WT, et al. Increased readmission risk and healthcare cost for delirium patients without immediate hospitalization in the emergency department. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci 2018;16:398–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. NRD Database Documentation. NRD Description of Data Elements. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.NRD Database Documentation. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roffman CE, Buchanan J, Allison GT. Charlson comorbidities index. J Physiother 2016;62:171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crocker E, Beggs T, Hassan A, et al. Long-term effects of postoperative delirium in patients undergoing cardiac operation: a systematic review. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;102:1391–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terman SW, Reeves MJ, Skolarus LE, Burke JF. Association between early outpatient visits and readmissions after ischemic stroke. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2018;11:e004024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rumalla K, Smith KA, Arnold PM, Schwartz TH. Readmission following surgical resection for intractable epilepsy: nationwide rates, causes, predictors, and outcomes. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2019;16:374–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang JW, Cifrese L, Ostojic LV, Shah SO, Dhamoon MS. Preventable readmissions and predictors of readmission after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care 2018;29:336–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goto T, Faridi MK, Gibo K, et al. Trends in 30-day readmission rates after COPD hospitalization, 2006–2012. Respir Med 2017;130:92–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blecker S, Herrin J, Li L, Yu H, Grady JN, Horwitz LI. Trends in hospital readmission of Medicare-covered patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:1004–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffman GJ, Liu H, Alexander NB, Tinetti M, Braun TM, Min LC. Posthospital fall injuries and 30-day readmissions in adults 65 years and older. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e194276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome: an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med 2013;368:100–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koch CG, Li L, Sun Z, et al. Magnitude of anemia at discharge increases 30-day hospital readmissions. J Patient Saf 2017;13:202–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bottle A, Honeyford K, Chowdhury F, Bell D, Aylin P. Factors Associated With Hospital Emergency Readmission and Mortality Rates in Patients With Heart Failure or Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A National Observational Study. Southampton: NIHR Journals Library; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jasinski MJ, Lumley MA, Soman S, Yee J, Ketterer MW. Indicators of cognitive impairment from a medical record review: correlations with early (30-d) readmissions among hospitalized patients in a nephrology unit. Psychosomatics 2017;58:173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rubin DJ. Hospital readmission of patients with diabetes. Curr Diab Rep 2015;15:17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaiyachati KH, Qi M, Werner RM. Changes to racial disparities in readmission rates after Medicare's hospital readmissions reduction program within safety-net and non-safety-net hospitals. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e184154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alcala HE, Roby DH, Grande DT, McKenna RM, Ortega AN. Insurance type and access to health care providers and appointments under the affordable care act. Med Care 2018;56:186–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohseni M, Alikhani M, Tourani S, Azami-Aghdash S, Royani S, Moradi-Joo M. Rate and causes of discharge against medical advice in Iranian hospitals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran J Public Health 2015;44:902–912. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.El Sayed M, Jabbour E, Maatouk A, Bachir R, Dagher GA. Discharge against medical advice from the emergency department: results from a tertiary care hospital in Beirut, Lebanon. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e2788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar N. Burden of 30-day readmissions associated with discharge against medical advice among inpatients in the United States. Am J Med 2019;132:708–717.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edwards J, Markert R, Bricker D. Discharge against medical advice: how often do we intervene? J Hosp Med 2013;8:574–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hughes LD, Witham MD. Causes and correlates of 30 day and 180 day readmission following discharge from a Medicine for the Elderly Rehabilitation unit. BMC Geriatr 2018;18:197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data not published within this article are available in a public repository, NRD derived from HCUP's for the year 2014. We used NRD visit link (NVL) to identify index hospitalizations for delirium and to track readmissions following the index admission.