Abstract

Objective

Postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS), the most common form of dysautonomia, may be associated with autoimmunity in some cases. Autoantibodies against the ganglionic acetylcholine receptor (gAChR) have been reported in a minority of patients with POTS, but the prevalence and clinical relevance is unclear.

Methods

Clinical information and serum samples were systematically collected from participants with POTS and healthy control volunteers (n = 294). The level of positive gAChR antibodies was classified as very low (0.02–0.05 nmol/L), low (0.05–0.2 nmol/L), and high (>0.2 nmol/L).

Results

Fifteen of 217 patients with POTS (7%) had gAChR antibodies (8 very low and 7 low). Six of the 77 healthy controls (8%) were positive (3 very low and 3 low). There were no clinical differences between seropositive and seronegative patients with POTS.

Conclusions

Prevalence of gAChR antibody did not differ between POTS and healthy controls, and none had high antibody levels. Patients with POTS were not clinically different based on seropositivity. Low levels of gAChR antibodies are not clinically important in POTS.

Postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is estimated to affect up to 3 million Americans.1 This syndrome is defined by an excessive increase in heart rate on standing with orthostatic symptoms in the absence of hypotension.2 Symptoms can include lightheadedness, blurred vision, cognitive difficulty, palpitations, gastrointestinal distress, tremulousness, fatigue, and weakness. The typical patient with POTS is a young woman (female: male ratio 4.5:1). Associated comorbid conditions are common, including migraine headache, gastrointestinal dysmotility, joint hypermobility, and autoimmune disorders.3 The cause of POTS is likely multifactorial, and autoimmunity is believed to play a role in some patients with subacute onset after infection, physical injury, immunization or surgery, a personal or family history of autoimmune disease, or laboratory evidence of autoimmunity.4,5

The ganglionic nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (gAChR) mediates synaptic transmission in all autonomic ganglia.6 Antibodies against gAChR are found at high levels in autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy,7 a disorder of severe diffuse autonomic failure that may respond to immunomodulatory treatment.8 These antibodies (at low levels) have also been reported in POTS with prevalence as high as 14% in 1 study.9 In real-world practice, the prevalence seems to be much lower, and the interpretation of gAChR antibody in POTS remains unclear.4 In other studies, more than 50% of patients with low levels of gAChR antibody had no evidence of an autoimmune neurologic disorder.10 This antibody may be found in 3%–4% of healthy controls.11 Variability in normal values used by commercial laboratories further complicates the interpretation of gAChR antibody results in clinical practice.12

Methods

This analysis was part of an observational study to characterize antibody prevalence in community patients with POTS and contemporary healthy controls. Participants were recruited onsite at either the 2014 or the 2016 annual patient and caregiver conference sponsored by Dysautonomia International. Interested participants were informed of the study protocol and provided informed consent (n = 173 in 2014 and n = 152 in 2016). Twenty-four patients participated in both the 2014 and 2016 cohorts; to ensure these participants were only counted once, their data from 2016 were not included in the combined analysis. The POTS group consisted of those who reported being diagnosed with POTS by a physician, and the self-reported healthy controls gave no history of an autoimmune or autonomic disorder. Eight patients reporting an autonomic diagnosis other than POTS were excluded. The final study cohort included 217 patients with POTS and 77 healthy controls. Because of the method of recruitment at a POTS conference, many of the healthy controls were related to patients with POTS.

Participants completed multiple questionnaires that addressed symptoms and medical history and standardized assessments of fatigue, symptom burden, and quality of life. An autonomic specialist measured supine and standing heart rate and blood pressure during supine rest and at intervals during a 10-minute active stand test. Patients reported symptoms that arose during standing using the Vanderbilt Orthostatic Symptom Score near the end of the stand. The Beighton score for joint hypermobility was determined by examination. Antibodies against gAChR were measured using radioimmunoprecipitation assay (as described previously),8 and antibody levels were categorized as very low (0.02–0.05 nmol/L), low (0.05–0.2 nmol/L), and high (>0.2 nmol/L).

Data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools.13 Statistical comparisons were analyzed using SPSS v26 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Fisher exact tests or χ2 tests were used for categorical variables, as appropriate. Continuous measures were analyzed using both independent samples t tests and Mann-Whitney U tests. Because the p values were very similar between the parametric and nonparametric analyses, only t test results were reported. For the t test results, if group variances were significantly different, nonpooled t test results were used.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

The project was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards at UT Southwestern (IRB#042016-036) and Vanderbilt University (IRB#140671). All participants provided written informed consent.

Data Availability

Anonymized data not published within this article will be made available by request from any qualified investigator.

Results

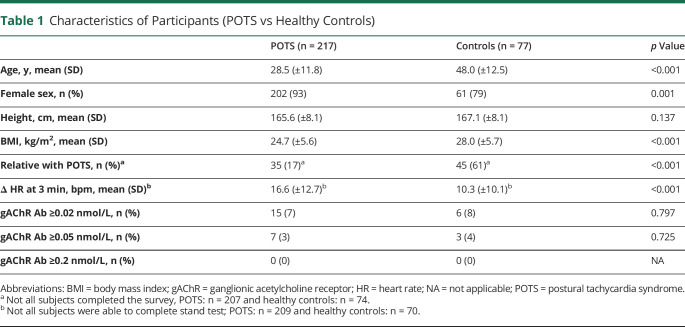

Among included participants, 217 reported receiving a formal POTS diagnosis from a physician and 77 were healthy controls. The participant demographics are shown in table 1. Patients with POTS were younger, more often women, and had a lower body mass index.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants (POTS vs Healthy Controls)

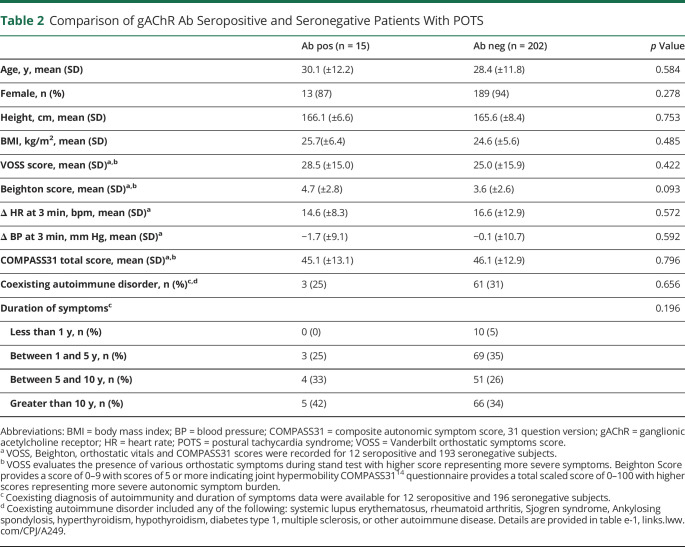

Fifteen patients with POTS (8 very low and 7 low) and 6 healthy controls (3 very low and 3 low) were positive for gAChR antibodies. The prevalence of gAChR antibody in POTS and controls was not different (table 1). The clinical characteristics of patients with POTS with gAChR antibodies were not different from seronegative patients (table 2). Orthostatic vital signs, symptom severity, symptom duration, and frequency of self-reported coexisting autoimmune diagnosis were not significantly different between seropositive and seronegative POTS groups (table 2 and table e-1, links.lww.com/CPJ/A249).

Table 2.

Comparison of gAChR Ab Seropositive and Seronegative Patients With POTS

Discussion

Consistent with previous retrospective reports, low levels of gAChR antibodies are found in a small percentage of patients with POTS. The frequency of gAChR antibodies in patients with POTS (3%–7% depending on the cutoff value) was not different from the frequency of this antibody in healthy controls and not different from the positivity rates in healthy controls reported elsewhere.11 All seropositive participants in this study (healthy controls or POTS) had low antibody levels (≤0.13 nmol/L). Low gAChR antibody levels may be found in patients with various autoimmune diseases or with cancer10,12 and in healthy controls.11 Low gAChR antibody levels (<0.2 nmol/L), therefore, have poor clinical specificity and must be interpreted with caution. Patients with POTS with low-level gAChR antibodies should not have additional extensive diagnostic testing or immunotherapy based on this test result alone.

The strength of this study is the examination of a broad cross section of community patients with POTS and controls enrolled in a standardized way. This approach yields a more accurate picture of the serologic profile of POTS in real-world practice compared with previous studies from academic centers where referral bias may affect the study population. Our patients and controls were self-identified at a patient and family conference, which may have introduced a volunteer bias leading to inclusion of some participants who did not have POTS or selecting for patients with POTS who were healthy enough to travel to a patient conference. Indeed, although most continued to have symptomatic orthostatic intolerance, only a minority of patients met the clinical heart rate criteria for POTS at the time of the study enrollment (patients were allowed to continue symptom therapies and medications during the standing test that likely affected the magnitude of the orthostatic tachycardia). Regardless, the use of symptomatic medications for orthostatic or other symptoms would not affect the serologic findings presented in this study.

Low levels of gAChR antibody may be found in a small minority of patients with POTS at a frequency similar to healthy controls indicating that the presence of low levels of gAChR antibody in POTS have no clinical importance.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

→ Patients with POTS may have clinical features suggesting an autoimmune condition.

→ In a community population, the prevalence of low levels of ganglionic AChR antibodies in POTS was similar to that of healthy controls.

→ Low levels of ganglionic AChR antibody (<0.2 nmol/L) in POTS are not associated with any clinical phenotype and seem to have little, if any, clinical importance.

Acknowledgment

We thank the patients with POTS and healthy volunteers who participated in this study.

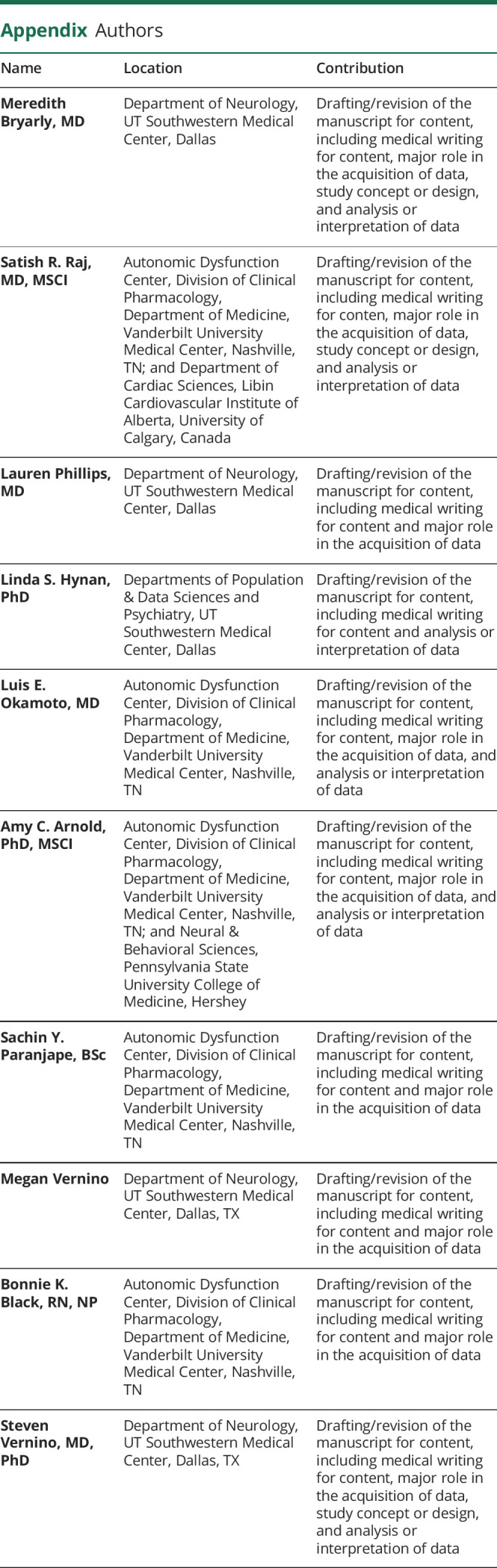

Appendix. Authors

Study Funding

Funded by a grant from Dysautonomia International. This work was also supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Grants UL1TR000445, UL1TR001105, and UL1RR024982.

Disclosure

M. Bryarly: consultant for BioHaven and Biogen; and research support from Theravance Biopharma USA, Grifols and Dysautonomia International. S.R. Raj: consultant for Lundbeck NA Ltd., Theravance Biopharma USA, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Medscape LLC, Spire Learning, and Academy for Continuing Healthcare Learning GE Healthcare, Abbott and Allergan. L. Phillips: consultant for ACI Clinical - Neurology Endpoint Adjudication Committee; research support from NINDS, Grifols and Dysautonomia International. L.S. Hynan performed the statistical analysis and reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. L.E. Okamoto reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. A.C. Arnold: consultant for Vaccine Injury Compensation Program, Department of Health and Human Services. S.Y. Paranjape reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. M. Vernino: currently employed by Pfizer and reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. B.K. Black reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. S. Vernino: consultant for Catalyst, Alterity and Sage Therapeutics; and research support from BioHaven, Genentech, Grifols, Dysautonomia International, and Quest Diagnostics (through a licensing agreement). Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

References

- 1.Raj SR, Robertson D. Moving from the present to the future of postural tachycardia syndrome: what we need. Auton Neurosci 2018;215:126–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheldon RS, Grubb BP, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm 2015;12:E41–E63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaw BH, Stiles LE, Bourne K, et al. The face of postural tachycardia syndrome: insights from a large cross-sectional online community-based survey. J Internal Med 2019;286:438–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vernino S, Stiles LE. Autoimmunity in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: current understanding. Auton Neurosc 2018;215:78–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryarly M, Phillips LT, Fu Q, Vernino S, Levine BD. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: JACC focus seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:1207–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vernino S, Hopkins S, Wang Z. Autonomic ganglia, acetylcholine receptor antibodies, and autoimmune ganglionopathy. Auton Neurosci 2009;146:3–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cutsforth-Gregory JK, McKeon A, Coon EA, et al. Ganglionic antibody level as a predictor of severity of autonomic failure. Mayo Clin Proc 2018;93:1440–1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vernino S, Low PA, Fealey RD, Stewart JD, Farrugia G, Lennon VA. Autoantibodies to ganglionic acetylcholine receptors in autoimmune autonomic neuropathies. N Engl J Med 2000;343:847–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thieben MJ, Sandroni P, Sletten DM, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: the Mayo Clinic experience. Mayo Clin Proc 2007;82:308–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKeon A, Lennon VA, Lachance DH, Fealey RD, Pittock SJ. Ganglionic acetylcholine receptor autoantibody: oncological, neurological, and serological accompaniments. Arch Neurol 2009;66:735–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lang K, Pruss H. Frequencies of neuronal autoantibodies in healthy controls: estimation of disease specificity. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2017;4:e386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y, Jammoul A, Mente K, et al. Clinical experience of seropositive ganglionic acetylcholine receptor antibody in a tertiary neurology referral center. Muscle Nerve 2015;52:386–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sletten DM, Suarez GA, Low PA, Mandrekar J, Singer W. COMPASS 31: a refined and abbreviated composite autonomic symptom score. Mayo Clin Proc 2012;87:1196–1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data not published within this article will be made available by request from any qualified investigator.