Abstract

Background and study aims Anticoagulation (AC) and antiplatelet (AP) therapy may increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding after double balloon enteroscopy (DBE); however, limited data are currently available regarding the incidence. The aim of this study was to assess the incidence and clinical characteristics of post-DBE bleeding in patients on AC and AP therapy.

Patients and methods The medical records of patients who underwent DBE between 2009 and 2013 at Mayo Clinic, Florida, were retrospectively reviewed. Patients were divided into three groups: 1) continued AP therapy; 2) AC therapy; and 3) neither AP nor AC at the time of DBE. Follow-up data were collected at 60 days and 1 year.

Results A total of 683 patients were identified; 43 on AC, 183 on AP and 457 not on AP or AC therapy. The most common indication for DBE was obscure gastrointestinal bleeding in the groups on and not on AP (85.3 % vs 70.9 %, P < 0.0001). There was no statistical difference in post-DBE bleeding rates in patients on AP vs not on AP at 60 days (11.5 % vs 7.5 %, P = 0.12) or 1 year (19.9 % vs 15.7 %, P = 0.23). Rates of bleeding in patients on AC were 11.6 % within 60 days and 22.5 % within 1 year. Multivariate analysis reflected American Society of Anesthesiologist > 3 and indication for DBE of GI bleeding were independent risk factors for post-DBE bleeding within 1 year.

Conclusions Continued antiplatelet use at the time of DBE was not an independent risk factor for bleeding post-DBE at 60 days or 1 year of follow up.

Introduction

Small bowel disorders are often challenging to diagnose and treat, given the tortuous anatomy of the small bowel, its location, and length 1 . Capsule enteroscopy (CE) is a reliable noninvasive diagnostic tool for screening for small bowel pathology, but lacks the therapeutic element 2 . Therefore, the introduction of double balloon enteroscopy (DBE) in 2003 filled a major gap in the diagnosis and treatment of small bowel disorders 3 . Overall, DBE is a well-tolerated procedure for both adults and the elderly despite its technique complexity and the lengthy procedure time 4 .

Complication rates for DBE have been reported to be comparable to standard endoscopic procedures, including perforation (0.4 %), pancreatitis (0.2 %) and bleeding (0.2 %) 4 5 . Similar to any post-endoscopic bleeding, post-DBE bleeding may occur in the short or long post-procedural interim, depending on the indication for the procedure and therapeutic intervention pursued 6 . Current American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines recommend holding antiplatelet (AP)/anticoagulant (AC) therapy in high-risk bleeding procedures including therapeutic DBE 7 . However, continuation of AP/AC therapy could, theoretically, provoke bleeding during DBE, facilitating the identification of the source, especially in patients who present with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, the most common indication for DBE 8 9 .

To our knowledge, limited data are available regarding the effect of continuing AP and AC therapy on post-DBE bleeding. Therefore, we aimed to assess the risk of bleeding following DBE in patients who did not have AP therapy held prior to the procedure compared to patients who were on AP therapy. We also aimed to descriptively analyze the risk of post-DBE bleeding in a small cohort of patients who did not have AC therapy held prior to DBE.

Patients and materials

Study design

This was a retrospective, single-center study of consecutive patients who underwent DBE between 2009 and 2013 at Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Florida. Patients were divided into three groups:

those on continued AP therapy at the time of DBE;

those on continued AC therapy at the time of DBE; and

those who were not on either therapy at the time of DBE.

Data were manually collected through electronic medical record review and included demographics, comorbidities, laboratory values, enteroscopy indication, approach (antegrade, retrograde, both), intervention, and medication use at the time of procedure. The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Defining variables and outcomes

Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) was defined as persistent iron deficiency whose source was not identified by either esophagastroduodenoscopy or colonoscopy and excluded patients with malignancy or other hematologic comorbidity. Abnormal computed tomography (CT) was defined as imaging indicative of a small bowel mass requiring DBE for biopsy.

Post-DBE bleeding was defined as follows:

Repeated DBE, urgent endoscopy or surgery within 60-days of procedure for persistent symptoms of melena, hematochezia, or acute anemia;

Clinical documentation of melena, hematochezia, or acute anemia requiring hospitalization within 60-days of procedure by any department or available outside hospital records; and

A transfusion requirement within 60 days of procedure.

“No-post-DBE bleeding” within 60 days was defined as follows:

Clinical documentation available within 60 days endorsing resolution of presenting symptoms (hematemesis, hematochezia, melena) prompting index DBE;

Absence of blood transfusion within time frame of procedure, transfusion documentation; and

No readmission requiring DBE.

The above criteria were also applied to follow-up 1 year following DBE.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were summarized with the sample median and range. Categorical variables were summarized with number and percentage of patients. Comparisons between groups were made using a Wilcoxon rank sum test or Fisher’s exact test. The comparative analysis for the AP group did not include any of the patients who were on AC or combined AC + AP therapy Univariate analysis was performed to identify significant risk factors predicting bleeding within 60 days and 1 year of DBE, separately. We built our multivariate model to include variables that were statistically significant on the univariate analysis and those which are clinically relevant. Adjusted odd ratios (AOR) were reported. All tests were two-sided with alpha level set as 0.05 for statistical significance. Based on the medical opinion of clinical experts in advanced endoscopy, the anticipated difference in bleeding following DBE in both cohorts was determined to be 5 %. A minimum of 152 samples per group were required to achieve 80 % power with a two-sided test at a significance level of 5 %, assuming a binomial variance inflation factor of 1. Statistical analysis was performed using JMP, version 14.1.0, SAS Institute Inc. NC, 1989–2019.

Results

Patient demographics

A summary of the study population selection is illustrated in Fig. 1 . A total of 755 patients were identified using Mayo Clinic’s DBE Database, of which, 72 patients were excluded due to lack of follow-up data. Of the 683 patients with follow-up data, 43 patients were on AC therapy. Of the remaining 640 patients, 183 were on continued AP therapy at the time of DBE and 457 were not on AP or AC therapy.

Fig. 1.

Summary of the study population.

Patients on AP therapy were older (71.3 vs 63.7, P < 0.0001), had male predominance (55 % vs 42 %, P = 0.003), and more likely to smoke (72.9 % vs 53.9 %, P < 0.0001) compared to patients who were not on AP therapy. There was no statistical difference in BMI between the cohorts, as shown in Table 1 .

Table 1. Demographics and clinical characteristics of patients on and not on antiplatelet therapy.

| On antiplatelet therapy (N = 183) | Not on antiplatelet therapy (N = 457) | P value | |

| Demographics | |||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 71.3 ± 9.5 | 63.7 ± 14.7 | < 0.0001 |

| Sex (M) | 100 (55 %) | 191 (42 %) | 0.003 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD) | 29.4 ± 6.4 | 28.6 ± 7.2 | 0.18 |

|

42 (23.3) | 126 (28.6) | 0.19 |

|

60 (33.3) | 131 (29.7) | 0.44 |

|

35 (19.4) | 85 (19.3) | 1.00 |

|

25 (13.9) | 54 (12.2) | 0.59 |

|

11 (6.1) | 25 (5.7) | 0.85 |

| Smoking (%) | 132 (72.9) | 242 (53.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| American Society of Anesthesiologists Classification (ASA Class) | |||

|

1 (0.6) | 12 (2.82) | 0.12 |

|

64 (38.1) | 202 (47.5) | 0.047 |

|

99 (58.9) | 195 (45.9) | 0.0047 |

|

4 (2.4) | 16 (3.8) | 0.61 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 70 (38.7) | 96 (21.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 153 (84.1) | 275 (61.1) | < 0.0001 |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 2 (1.1) | 18 (3.9) | 0.077 |

| Chronic kidney disease (%) | 27 (14.9) | 42 (9.4) | 0.0487 |

| Medications | |||

| Antiplatelet therapy | |||

|

7.9 %) | – | |

|

47 (25.6 %) | – | |

|

30 (16.4 %) | – | |

| SSRI (%) | 32 (17.5) | 68 (15.0) | 0.47 |

| NSAIDs other than aspirin (%) | 23 (12.6) | 85 (18.7) | 0.063 |

BMI, body mass index; NSAID, nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drug.

Forty-three patients were identified to be on continued AC therapy at the time of DBE, 14 of whom (32.6 %) were on both AC and AP therapy. AC patients had a median age of 71 years and were predominantly male (58 %). AC therapy included warfarin, rivaroxaban, apixaban, dabigatran, enoxaparin, and therapeutic heparin drip infusion, as shown in Table 2 .

Table 2. Demographics and characteristics for patients on anticoagulation.

| Anticoagulation (N = 43) | |

| Demographics | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 71.1 ± 10.1 |

| Sex (M) | 21 (58.3 %) |

| Anticoagulation | |

|

30 |

|

1 |

|

1 |

|

2 |

|

2 |

|

1 |

|

6 |

| Antiplatelets + anticoagulation | 14 (32.6 %) |

| Enteroscopy characteristics | |

| Approach | |

|

19 |

|

10 |

|

14 |

| Indication | |

|

36 |

|

3 |

|

1 |

|

3 |

| Intervention | |

|

10 |

|

17 |

|

9 |

|

7 |

| Bleeding within 60 days on anticoagulation | 5/43 (11.6 %) |

| Bleeding within 1 year on anticoagulation | 9/40 (22.5 %) |

CT, computed tomography; APC, argon plasma coagulation.

Clinical characteristics

Based on the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification system, patients on AP therapy were more likely to be ASA 3 (58.9 % vs 45.9 %, P < 0.0047) compared to those who were not on AP therapy. In addition, comorbidities of diabetes mellitus (38.7 % vs 21.3 %, P < 0.0001), hypertension (84.1 % vs 61.1 %, P < 0.0001), and chronic kidney disease (14.9 % vs 9.4 P = 0.0487) were more likely to be found in patients on AP therapy compared to those not on AP therapy. There was no difference between the cohorts with regard to cirrhosis, as shown in Table 1 . Of the patients on AP therapy, 57 % were on aspirin, 25.6 % on clopidogrel, and 16.4 % on both medications (dual antiplatelet therapy). There was no difference in distribution in either cohort with regards to SSRI use or NSAIDs other than aspirin.

Enteroscopy characteristics

Iron deficiency anemia was the most common presenting symptom in both patients on and not on AP (80.2 % vs 57.9 %, P < 0.0001). The most common indication for DBE was OGIB (85.3 % vs 70.9 %, P < 0.0001). Patients on AP therapy were more likely to have a DBE conducted with an antegrade approach (54.6 % vs 42.6 %, P = 0.0065) with an intra-procedural intervention, in particular argon plasma coagulation (APC) therapy (67.1 % vs 36.3 %, P < 0.0001), compared to those who were not on AP therapy as shown in Table 3 . Enteroscopy characteristics of patients who were on AC therapy are summarized in Table 2 .

Table 3. Enteroscopy characteristics for patients on vs non on antiplatelet therapy.

| Enteroscopy characteristics | On antiplatelet therapy (N = 183) | Not on antiplatelet therapy (N = 457) | P value |

| Presenting symptom | |||

|

6 (5.0) | 61 (18.2) | 0.0003 |

|

97 (80.2) | 194 (57.9) | < 0.0001 |

|

2 (1.7) | 19 (5.7) | 0.079 |

|

2 (1.7) | 29 (8.7) | 0.0059 |

|

4 (3.3) | 34 (10.2) | 0.0203 |

|

1 (0.8) | 9 (2.7) | 0.303 |

|

38 (31.4) | 110 (32.8) | 0.8213 |

| Approach | |||

|

100 (54.6) | 194 (42.6) | 0.0065 |

|

37 (20.2) | 138 (30.3) | 0.0106 |

|

46 (25.1) | 124 (27.3) | 0.6214 |

| Indication | |||

|

12 (6.6) | 23 (5.0) | 0.445 |

|

168 (91.8) | 352 (77.0) | < 0.0001 |

|

5 (2.7) | 28 (6.1) | 0.1115 |

|

5 (2.7) | 47 (10.3) | 0.0011 |

|

1 (0.6) | 9 (2.0) | 0.2958 |

|

1 (0.6) | 6 (1.3) | 0.6795 |

|

1 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | 0.4904 |

|

1 (0.6) | 32 (7.0) | 0.0002 |

|

10 (5.5) | 26 (5.7) | 1.00 |

| Intervention | |||

|

17 (10.4) | 77 (19.0) | 0.0124 |

|

110 (67.1) | 147 (36.3) | < 0.0001 |

|

0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 1.00 |

|

1 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 0.4937 |

|

42 (25.6) | 165 (40.7) | 0.0007 |

|

1 (0.6) | 2 (0.5) | 1.00 |

|

1 (0.6) | 6 (1.5) | 0.6793 |

|

15 (9.2) | 32 (7.9) | 0.6169 |

| Total procedure time (min) (mean ± SD) | 72.3 (39.5) | 70.9 (38.7) | 0.5985 |

CT, computed tomography; APC, argon plasma coagulation.

Clinical outcomes

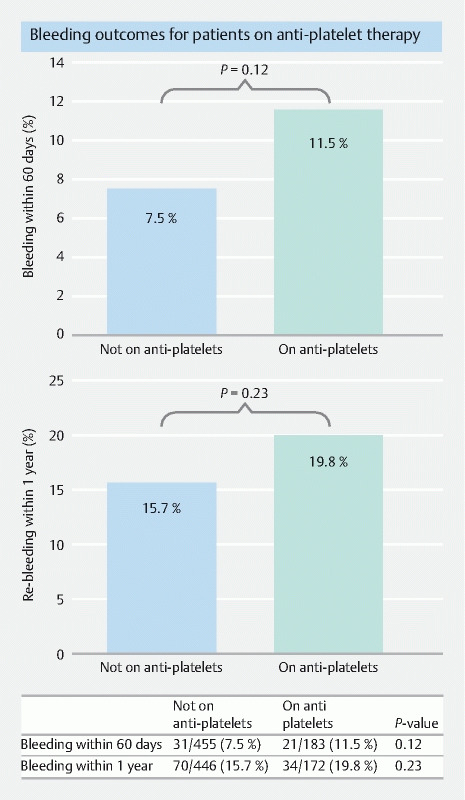

Of the 640 identified patients, 637 patients had available follow-up data at 60 days (3 died) and 618 at 1 year (22 died). There was no statistical difference when comparing bleeding outcomes in patients on continued AP therapy vs not on AP therapy at 60 days (11.5 % vs 7.5 %, P = 0.12) or 1 year (19.9 % vs 15.7 %, P = 0.23) post-DBE as illustrated in Fig. 2 . For patients on continued AC therapy, 11.6 % bled within 60 days and 22.5 % bled within 1 year following DBE as shown in Table 2 .

Fig. 2.

Bleeding outcomes of patients on antiplatelet vs not on antiplatelet therapy at 60 days and 1 year.

Univariate analysis to identify independent risk factors for bleeding within 60 days of DBE was significant for age > 50 (OR 9.75, CI 1.33–1.37, P = 0.0250), ASA > 3 (OR 2.63, CI 1.40–5.0, P = 0.017) and the initial indication for DBE performed for gastrointestinal bleeding (OR 2.76, CI 1.08–7.08, P = 0.0166). After adjusting for age, sex, antiplatelet use, ASA comorbidity index, and DBE indication via performing a multivariate analysis, there were no statistically significant risk factors identified for bleeding within 60 days ( Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of bleeding outcomes at 60 days and 1 year.

Similarly, a univariate analysis to assess for risk of bleeding at 1 year following DBE was significant for ASA > 3 (OR 1.86, CI 1.19–2.93, P = 0.0057) and initial indication for DBE performed for bleeding (OR 2.86, CI 1.44–5.66, P = 0.0008). After adjusting for the variables mentioned above via a multivariate analysis, ASA > 3 (AOR 1.72, CI 1.01–2.90, P = 0.0389) and indication for DBE; bleeding (AOR 3.06, CI 1.48–6.36, P = 0.0010) were identified to be independent risk factors for bleeding within 1-year following DBE ( Fig. 3 ).

Continued AP use was not found to be a predicting factor for bleeding post-DBE at 60 days or 1-year follow up.

Discussion

Rebleeding rates following DBE have been reported to be as low as 3 % and as high as 40 %, depending on the indication for the procedure, follow-up period, and differences in defining rebleeding events 6 10 . Bleeding events may be a complication of the procedure itself or simply represent the natural progression of small bowel lesions such as arteriovascular malformations (AVMs) which often bleed recurrently 11 . The clinical impact of continuing AC and AP therapy throughout DBE on the rates of rebleeding is understudied. Current ASGE guidelines recommend holding AP/AC therapy in patients with a high risk of bleeding who undergo therapeutic DBE 7 . However, a counter theory would support continuing those therapies as a diagnostic bleeding-provocation test, which may allow for the identification of a higher number of lesions and hence, treatment optimization 12 13 . Our study showed that patients who did not discontinue AP therapy before DBE had statistically similar rates of bleeding at 60 days (11.5 % vs 7.5 %, P = 0.12) and 1 year (19.9 % vs 15.7 P = 0.23), when compared to patients who were not on AP therapy. The bleeding rate in our AC cohort was similar at 60 days and one year at 11.6 % and 22.5 %, respectively. On a multivariate analysis, continued anti-platelet use was not an independent predictor of post-DBE bleeding at 60-day or 1-year follow-up.

Our review of the literature identified two studies that evaluated the risk of post-DBE rebleeding in patients on AP or AC therapy, presenting for evaluation of OGIB. Both studies were only available in abstract form, which limited commentary regarding methodology and statistical analysis. Bhattacharya et al. found 0 patients in their 1447 patient cohort that had intraoperative or delayed (30 days) rebleeding post DBE 8 . Spencer et al. with a total cohort of 86 patients reported a rebleeding rate post-DBE was 5.8 % in patients at 30 days and 12.8 % at 60 days 9 . Both studies reported no statistically significant association between AP/AC use and post-DBE rebleeding. Our study reports bleeding rates of 11.5 % in patients on AP therapy and 11.6 % in patients on AC therapy at 60-day follow-up. At 1 year, we found rebleeding to be 19.9 % and 22.5 % respectively. The 60-day outcomes are likely reflective of post-DBE-related bleeding, while the 1-year follow-up outcomes are more likely reflective of the effectiveness of DBE therapy, most for GIB, in our institution. Compared to those studies, our study incorporated a more detailed description of our methodology. In addition, we evaluated more drug classes and included a wider variety of initial symptoms and indices requiring DBE. Our patients were also treated with more types of interventions with longer outcomes follow-up data, which better reflects real clinical practice.

Rebleeding rates following DBE are the highest (around 40 %–60 % at 12- to 36-month follow-up) in patients presenting exclusively with small bowel vascular lesions 6 11 14 15 . In spite of the fact that we defined post-DBE bleeding similarly to Bhattacharya and Spencer, we reported lower rates of bleeding, which may have more than one possible explanation. Although most of our cohort presented with OGIB and was found to have vascular lesions treated with APC therapy, we still included patients with different presentations and indications for DBE, which may have lowered the total rates of post-DBE bleeding. It is also possible that our data may be a reflection of a higher success rate in identifying the bleeding source, particularly in the group of patients on AP therapy.

The observed differences in demographics and clinical features between cases and controls in our study were expected. Patients on AP therapy were older and had more comorbidities than the ones in the non-AP group. In addition, we expected a higher incidence of vascular malformations, and therefore, obscure GIB requiring an endoscopic intervention in the AP group. After adjusting for those differences, AP use was not predictive of post-DBE bleeding at 60-day or 1-year follow-up. Our data support the findings of a study conducted by Samaha et al., who did not find AP or AC therapy to be independent risk factors for post-DBE rebleeding. However, it was not reported if AP/AC therapy was continued at the time of the procedure. In their study, the number of vascular lesions and the presence of valvular/cardiac disease were the only risk factors for post-DBE bleeding 11 . We also found that ASA > 3 (AOR 1.72, CI 1.01–2.90, P = 0.0389) and indication for DBE of GIB (AOR 3.06, CI 1.48–6.36, P = 0.0010) were independent risk factors for bleeding within 1 year following DBE. This is likely explained by the natural history of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, which is usually recurrent; also, patients with higher ASA are more likely to be prescribed AP therapy and have more cardiovascular risk, leading to an increased risk of long-term bleeding rates.

We recognize our study is not free of limitations. The retrospective nature may have introduced biases in the data collection. This study was conducted at a tertiary-referral center, in which many patients were referred from different parts of the country and overseas. This made in-person follow-up data difficult to obtain, especially in our limited AC cohort. The number of patients on AC was small, which prevented us from performing a comparative analysis of this group. Despite these limitations, we believe our study adds to an area of great clinical importance currently supported by limited literature.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study showed no statistical difference in post-DBE bleeding rates in patients on continued AP therapy compared to patients who were not on AP therapy at 60 days and 1 year. This finding can potentially benefit endoscopists by using continued AP therapy as a bleeding-provocation test without worrying about increased rates of post-DBE bleeding; however, more studies are needed to investigate that hypothesis.

Footnotes

Competing interests The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Saygili F, Saygili S M, Oztas E. Examining the whole bowel, double balloon enteroscopy: Indications, diagnostic yield and complications. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:247–252. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i3.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rondonotti E. Capsule retention: prevention, diagnosis and management. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5:198. doi: 10.21037/atm.2017.03.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamamoto H, Yano T, Kita H.New system of double-balloon enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of small intestinal disorders Gastroenterology 20031251556author reply 1556–1557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang L, Xie M, Hong L et al. The Diagnostic yields and safety of double-balloon enteroscopy in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding and incomplete small bowel obstruction: comparison between the adults and elderly. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2020;2020:8.121625E6. doi: 10.1155/2020/8121625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moschler O, May A, Muller M K et al. Complications in and performance of double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE): results from a large prospective DBE database in Germany. Endoscopy. 2011;43:484–489. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerson L B, Batenic M A, Newsom S L et al. Long-term outcomes after double-balloon enteroscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:664–669. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee . Acosta R D, Abraham N S et al. The management of antithrombotic agents for patients undergoing GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhattacharya A. Rate of bleeding on antiplatelet and anticoagulant agents in patients undergoing double balloon enteroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:AB63. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spencer C N. Anticoagulation status and rebleeding following double balloon enteroscopy for obscure GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:AB339. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aniwan S, Viriyautsahakul V, Luangsukrerk T. Low rate of recurrent bleeding after double-balloon endoscopy-guided therapy in patients with overt obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:21149–2125. doi: 10.1007/s00464-020-07615-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samaha E, Rahmi G, Landi B et al. Long-term outcome of patients treated with double balloon enteroscopy for small bowel vascular lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:240–246. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar A, Gandolfo F, Halwan B. Provocation of bleeding during endoscopy in patients with recurrent acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2007;3:570. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raines D L, Jex K T, Nicaud M J et al. Pharmacologic provocation combined with endoscopy in refractory cases of GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.May A, Friesing-Sosnik T, Manner H et al. Long-term outcome after argon plasma coagulation of small-bowel lesions using double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with mid-gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2011;43:759–765. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shinozaki S, Yamamoto H, Yano T et al. Long-term outcome of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding investigated by double-balloon endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]