Abstract

This cohort study evaluates the prevalence of homebound older adults in the US from 2011 to 2020 and assesses whether the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with a change in prevalence.

Older adults who are homebound, defined as leaving home once a week or less, are often socially isolated, have unmet care needs, and have high mortality.1,2 In 2011, more older adults in the United States were homebound than living in nursing homes.1

The COVID-19 pandemic may have led to an increase in the number of homebound older adults who were at heightened risk for infection with SARS-CoV-2.3 Moreover, although Black non-Hispanic and Hispanic/Latino individuals have disproportionately died from COVID-19,4 it is unknown whether they were more likely to be homebound during the pandemic. We assessed the size and characteristics of the homebound population in the United States in 2020, including household size,5 important for disease transmission risks, and digital access, which is important for telemedicine and online vaccination registration.

Methods

We used data collected between May 1, 2011, and October 31, 2020, from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS), an annual cohort study of aging among community-dwelling older adults. The 2020 survey was conducted between May and October. Information about race, ethnicity, demographic characteristics, household size, Medicaid enrollment, self-reported health, comorbidities, and function was self-reported (Table). In 2020, respondents were asked whether they owned a cell phone or computer and whether in the last month they had used email or text, used the internet, or gone online.

Table. Demographic Characteristics, Household Size, and Technologic Environment Among Homebound Individuals in 2020a.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 658) | White non-Hispanic (n = 361) | Black non-Hispanic (n = 196) | Hispanic or Latino (n = 76) | ||

| Sociodemographic characteristics and health | |||||

| Age, y | |||||

| 70-74 | 59 (22.6) | 23 (16.3) | 16 (18.8) | 18 (47.6) | <.001 |

| 75-79 | 135 (24.0) | 60 (22.1) | 53 (32.2) | 16 (22.6) | |

| 80-84 | 139 (18.2) | 72 (19.3) | 49 (22.7) | 13 (10.7) | |

| 85-89 | 161 (18.9) | 101 (23.4) | 42 (15.6) | 13 (8.6) | |

| ≥90 | 164 (16.2) | 105 (18.8) | 36 (10.7) | 16 (10.4) | |

| Women | 479 (69.3) | 255 (67.9) | 156 (77.7) | 52 (66.4) | .46 |

| Men | 179 (30.7) | 106 (32.1) | 40 (22.3) | 24 (33.6) | |

| Medicaid | 172 (26.8) | 49 (14.4) | 71 (36.5) | 40 (56.1) | <.001 |

| Fair/poor health | 287 (42.7) | 138 (35.3) | 89 (43.6) | 46 (65.3) | <.001 |

| Anxietyb | 125 (19.9) | 67 (18.7) | 32 (14.1) | 20 (31.8) | .05 |

| Depressionc | 180 (28.8) | 99 (26.5) | 44 (24.5) | 30 (43.0) | .07 |

| Dementiad | 223 (28.3) | 131 (31.3) | 59 (23.9) | 23 (22.4) | .43 |

| Count of chronic conditionse | |||||

| 0 | 45 (11.4) | 30 (12.2) | 4 (1.9) | 7 (11.7) | .07 |

| 1 | 137 (25.3) | 80 (28.0) | 40 (24.8) | 11 (13.5) | |

| ≥2 | 476 (63.3) | 251 (59.8) | 152 (73.2) | 58 (74.8) | |

| ADL impairmentf | 324 (45.9) | 180 (49.2) | 93 (42.1) | 37 (37.6) | .37 |

| No. of others in the house | |||||

| 0 (Lives alone) | 248 (36.8) | 168 (43.7) | 59 (28.9) | 16 (26.8) | <.001 |

| 1 | 219 (34.7) | 125 (37.5) | 61 (33.5) | 24 (25.7) | |

| ≥2 | 191 (28.5) | 68 (18.8) | 76 (37.5) | 36 (47.6) | |

| Technologic environment | |||||

| No cell phone | 210 (27.8) | 127 (30.5) | 56 (21.6) | 20 (24.4) | .60 |

| No computer | 361 (50.8) | 176 (41.6) | 113 (57.9) | 57 (76.9) | <.001 |

| Did not email or textg | 307 (52.0) | 149 (45.1) | 98 (55.4) | 45 (67.8) | .01 |

| Did not go onlineg | 327 (55.2) | 153 (47.4) | 112 (66.3) | 48 (74.7) | .01 |

Abbreviation: ADL, activities of daily living.

Data from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) 2020. All estimates adjusted for survey design and weighting.

Anxiety was determined through a score of 2 or more on the General Anxiety Disorder–2 scale.

Depression was determined through a score of 2 or more on the Patient Health Questionnaire–2 scale.

Dementia was determined through both respondent/proxy report and cognitive assessments by NHATS staff.

Count of chronic conditions was ever reporting the number of the following conditions: heart attack, stroke, heart disease, lung disease, cancer, hypertension, and diabetes.

ADL, or receiving help with bathing, eating, dressing, toileting, or transferring.

Respondents were asked about email or texting and going online or using the internet in the last month.

After accounting for multiple observations of a single respondent, we assessed the prevalence of homebound status among adults aged 70 years or older annually by race and ethnicity. We applied NHATS sampling weights to derive national estimates of the population sizes and weighted proportions. Stata version 16 (StataCorp LLC) was used for analysis. Additional details of the methods are in the eAppendix in the Supplement. The NHATS research team conducted the interviews and obtained written informed consent. The institutional review board at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai approved the study.

Results

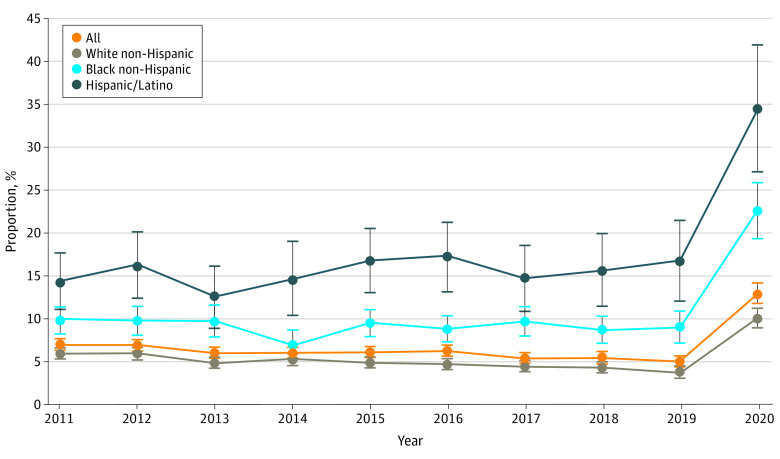

We identified 10 785 individuals aged 70 years or older, observed a mean (SD) of 4.6 (3.0) times, for 49 267 total observations during the 10 years of the study, including 3861 in 2020. Between 2011 and 2020, the prevalence of homebound adults aged 70 years or older more than doubled (Figure), from approximately 5.0% from 2011-2019 to 13.0% in 2020. In 2020, an estimated 4.2 million adults aged 70 years or older were homebound compared with 1.6 million in 2019. The prevalence of being homebound in 2020 was greatest among Hispanic/Latino individuals (34.5% homebound compared with 12.6%-17.2% in prior years), followed by Black non-Hispanic individuals (22.6% homebound compared with 6.9%-9.9% in prior years) and White non-Hispanic individuals (10.1% homebound compared with 3.7%-6.0% in prior years). Among those homebound in 2020, 47.6% of Hispanic/Latino individuals were aged 70 to 75 years compared with 22.6% of the overall population (Table). Black non-Hispanic and Hispanic/Latino homebound respondents were more likely to be receiving Medicaid than White non-Hispanic respondents and to report fair or poor health. Of homebound White non-Hispanic respondents, 43.7% lived alone compared with 28.9% of Black non-Hispanic respondents and 26.8% of Hispanic/Latino respondents. Compared with 18.8% of White non-Hispanic individuals, 47.6% of Hispanic/Latino individuals and 37.5% of Black non-Hispanic individuals lived with at least 2 others. Of the respondents, 27.8% did not have a cell phone, 50.8% did not have a computer, and more than half had not used email or texted (52.0%) or gone online (55.2%) in the last month. These proportions were highest among Hispanic/Latino homebound older adults, of whom 67.8% had not used email or texted in the last month, and 74.7% had not gone online.

Figure. Proportion of Community-Dwelling Older Homebound Adults Aged 70 Years or Older, 2011-2020.

Discussion

In the United States in 2020, we found that the proportion of community-dwelling homebound adults aged 70 years or older substantially increased, particularly among Black non-Hispanic and Hispanic/Latino individuals. Although our study could not establish the reasons for this first major increase in the homebound population in a decade, a likely explanation is compliance with social distancing and other public health recommendations to minimize the risk of infection with SARS-CoV-2. Our study also found notable racial and ethnic differences. For example, White non-Hispanic individuals were more likely to reside alone, which may have left them without caregiving assistance. In contrast, Black non-Hispanic and Hispanic/Latino individuals were more likely to live in multiperson households, which may have increased their risk of being exposed to SARS-CoV-2. Although the reason for higher rates of being homebound among Black non-Hispanic and Hispanic/Latino populations is unknown, it may be due to greater regional incidence of SARS-CoV-2 or reduced resources to safely navigate leaving home (eg, private transportation and safe grocery shopping options). The respondents, particularly Black non-Hispanic and Hispanic/Latino individuals, infrequently used digital technologies, a finding that is consistent with results of a prior study and has implications for equity regarding expanded telemedicine use.6 Other limitations of our study include that homebound rates may have fluctuated during the pandemic and by region, which we did not capture. The extent to which the increased prevalence of homebound older adults that we observed in 2020 will continue in 2021 as the COVID-19 pandemic abates, as well as the likely social, psychological, and physical effects, remains to be seen.

eAppendix. Further Details on Methods

References

- 1.Ornstein KA, Leff B, Covinsky KE, et al. Epidemiology of the homebound population in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1180-1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qiu WQ, Dean M, Liu T, et al. Physical and mental health of homebound older adults: an overlooked population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(12):2423-2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee A, Pasea L, Harris S, et al. Estimating excess 1-year mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic according to underlying conditions and age: a population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10238):1715-1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gross CP, Essien UR, Pasha S, Gross JR, Wang SY, Nunez-Smith M. Racial and ethnic disparities in population-level covid-19 mortality. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):3097-3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Figueroa JF, Wadhera RK, Mehtsun WT, Riley K, Phelan J, Jha AK. Association of race, ethnicity, and community-level factors with COVID-19 cases and deaths across US counties. Healthc (Amst). 2021;9(1):100495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts ET, Mehrotra A. Assessment of disparities in digital access among Medicare beneficiaries and implications for telemedicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(10):1386-1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Further Details on Methods