Abstract

Background and aim:

Understanding the patient’s experience of mental illness can foster better support for this population and greater partnership with healthcare professionals. This study aims to explore the application of visual methods in the psychiatric field and, in particular, the experience of people suffering from psychotic disorders, because it is still an open question that has not been only partially empirically examined.

Methods:

This qualitative study was conducted using two visual methods (auto-photography and photo-elicitation) associated with the narrative that emerged from an unstructured interview, in a clinical setting of adult Mental Health in Italy, between October 2019 and February 2020. A total of 5 patients and 5 corresponding referring healthcare professionals were identified and enrolled. Patients were asked to produce photographs following 4 thematic areas: “Fun”, “Time”, “Something indispensable”, “Place where I feel good”.

Results:

A total of 85 photographs were produced. Visual methods have proved to be a useful technique in qualitative research in the area of adult psychiatry. From the interviews it emerged that visual methods have allowed psychotic patients to use a new language to be able to communicate their emotions.

Conclusions:

The healthcare professionals involved also confirm the potential of this tool which, when combined with the traditional interview, is able to deepen the patient’s knowledge by overcoming the verbal barriers that often make it difficult to reconstruct the individual experience of illness.

Keywords: Visual methods, Photo-elicitation, Qualitative methods, Mental health services, Psychiatric patients, Experience of illness

Introduction

Chronic mental illness is a serious public health problem with difficulties in screening, treatment, drug adherence and quality of life for patients and their families (1-3). Understanding the patient’s experience of mental illness can foster better support for this population and greater partnership with healthcare professionals (4).

Over time, especially within anthropological studies, techniques that are able to level off differences caused by social and individual disadvantages have been developed (5). These techniques, defined as visual, have been incorporated with increasing enthusiasm within sociological studies as an alternative empirical tool to the traditional method dichotomies (qualitative-quantitative) (6-8). Visual techniques are those techniques used as an in-depth communicative language (9). Although they have been widely used in research, two main techniques that can be used for social research might be point out: photo-stimulation (or photo-elicitation) and auto-photography (10,11). The first technique can be defined as a variation of the semi-structured interview, in which photos are submitted instead of questions. The researcher will not have to ask for a series of information (as in the case of the interview) but remain very generic (What do you see in this photo? Who do you think these people are? Etc). It is possible, in a second phase, to divide the collected material into variables related to the main hypothesis (creation of an ad hoc grid). With the transition to digital it is possible to show the photos directly on the electronic device (pc, tablet, etc.) and it is no longer necessary to print them. This, of course, involves differences both with respect to the collection of the data and its treatment (12). The second visual technique is known as auto-photography. Auto-photography is a method of ethnographic research capable of creating an ecosystem in which researcher and reader see the world studied through the use of photography of its symbolic value, of its way of doing “clear and clean (13). Auto-photography can also give participants the opportunity to express themselves through the chosen images (7). Certainly one of the most important advantages recognized to visual techniques lies in the fact that through photography the interviewee has the opportunity to search for symbolic meanings that allow him/her to talk about himself/herself but not in the first person. These benefits have also been made known in psychiatric rehabilitation areas, where the language of phototherapy is used to bring out the experiences of fragile people (14). The Vancouver Photo Therapy Centre in Canada has been studying phototherapy for more than 35 years. In his text, “Photo Therapy: techniques and tools for the clinic and interventions in the field”, Weiser considers the approach to photography as any language of art that provides support for non-verbal interaction with the user; in essence, photography becomes a catalyst for personal analysis and a search engine for one’s own subconscious when words alone are not enough to express moods (15). In the psychiatric field, the use of techniques such as photography has a long history behind it: already in 1856 the London psychiatrist Hugh Welch Diamond, considered the father of psychiatric photography, used to photograph his patients to monitor their progress (16). Later this technique took on more varied forms, and in the field of mental health photography has evolved today essentially in the form of three methods: “photo art therapy”, “therapeutic photography” and “phototherapy” (17). Art therapy is a visual technique widely used in the field of mental health. It can take various purposes: for the patient with communication problems, drawing means expanding his/her possibilities of interaction with other, thus forming a channel of expression and communication through drawing; it can also be useful to bring out problems during an assessment which, otherwise carried out with traditional techniques, could remain hidden (18). Techniques such as self-portrait also help to bring out the individual characteristics and experiences of the person, as these are highly expressive techniques (19). More recent studies have validated the already consolidated theories on the use of visual techniques in mental health (20-24). Tuisku et al., to demonstrate what useful sources can be the expressive techniques flanked by classical methods of assessment, propose a mixed method research (22). On the basis of this statement, it is in fact verified that dissociative disorder is generally under-diagnosed and that typical symptoms are often described under different psychiatric diagnoses; this makes it difficult to identify a specific disorder (25). The authors asked several patients with dissociative symptoms to paint themselves in the way they perceived themselves, and then authors carried out a semi-structured interview aimed at exploring the drawings obtained. The use of visual techniques would seem to represent, especially if associated with other qualitative research methods (such as the interview), a valid tool that amplifies the patient’s expressive possibilities, revealing important and sometimes hidden meanings, an area in which the person’s problems are not always clearly explained and often require further investigation or clarification (23,26). Very few studies are available investigating understanding patients everyday life through photo-voice methods (4). This study aims to explore the application of visual techniques in the psychiatric field and, in particular, the experience of people suffering from psychotic disorders, because it is still an open question that has not been only partially empirically examined.

Methods

The goal of the research is to carry out daily life in psychotic patients through the use of visual methods, as well as the perceptions of the operators involved.

This monocentric qualitative study was conducted within this framework of meaning, using of two of the visual methods pertaining to the field of visual sociology, i.e. auto-photography and photo-elicitation (5,27-30), applied to the clinical setting of adult Mental Health in an Italian context, (Emilia Romagna Region, Ausl-IRCCS of Reggio Emilia), between October 2019 and February 2020.

The research was articulated along two main lines, consequential to each other: a first part, oriented to users, saw the use of the auto-photography technique associated with the narrative that emerged from an unstructured interview; a second phase, with the use of photo-elicitation and semi-structured interviews, aimed at referring operators for each patient interviewed, in a 1:1 operator-patient relationship. In both phases, the interviews were conducted in person and in a 1:1 ratio between researcher and interviewee.

Two main questions guided the research conducted in this study:

Does the possibility of using visual techniques (photo), describing one’s condition, allow to overcome the barriers that psychotic patient often encounters in the description of his/her daily life?

How do healthcare professionals relate to this innovative way of listening?

More generally, the objectives were the following:

c. Investigate the daily experiences of young patients suffering from psychotic disorders and therefore, more indirectly, aspects of the different dimensions of the disease;

d. Probe any points of proximity / discrepancy between patient and referring operator.

Both of the aforementioned points therefore envisaged the use of photography in a double ‘declination’ of auto-photography and photo-elicitation in the awareness of the complexity of the object of investigation, as brilliantly described by Prosser (31): «We accept that making pictures can be a threatening act (amply demonstrated by the metaphors photography invokes: we ‘load’, ‘aim’ and ‘shoot’) that yields an artificial product, an artefact of the idiosyncratic relationship among photographers and subjects, the medium, and the cultural expectations it generates».

The study population, as regards the “Patients group”, was sampled in the territorial contexts of the two Mental Health Centers (CSM) of Reggio Emilia and Scandiano (RE) of the Ausl-IRCCS of Reggio Emilia, in compliance with the following inclusion criteria:

age between 18 and 35 years.

diagnostic classification in the category of psychotic disorders;

gender balance;

possession of smartphone with camera;

The following were also considered as exclusion criteria:

comorbidity with documented cognitive fragility;

comorbidity with documented eating disorders;

acute phase of illness (hospital, residential or semi-residential setting);

criteria beyond the aforementioned inclusion criteria.

With respect to the “Healthcare professionals”, the criteria identified and adopted were the following:

work in one of the aforementioned CSMs as a doctor, or nurse, or professional educator, or psychiatric rehabilitation technician, or psychologist;

be a referring operator (unique or part of a micro-team) for at least one of the participating patients.

A total of 5 patients and 5 corresponding referring healthcare professionals were identified and enrolled. Patients were asked to produce photographs following 4 thematic areas (with the indication of a maximum of 5 photos per area):

Fun.

Time.

Something indispensable.

Place where I feel good.

A total of 85 photographs were produced, which were then selected by the researchers exclusively on the basis of a shared perception criterion for the purpose of analysing the results (specifically, 3 photographs per area). Furthermore, it was decided not to select photographs depicting people.

The interviews, with prior written consent, were fully audio-recorded, transcribed and thematically analyzed with anonymization of personal data and coding for each participant. The data, in compliance with the privacy statement, are stored in the archives of the Ausl-IRCCS company in Reggio Emilia.

Results

Fun!

As for the “fun” area, the interpretation of users interviewed highlighted a perception of fun as an area of “openness” to oneself and to others. Three photographs were selected that highlight this aspect and were divided into 3 themes:

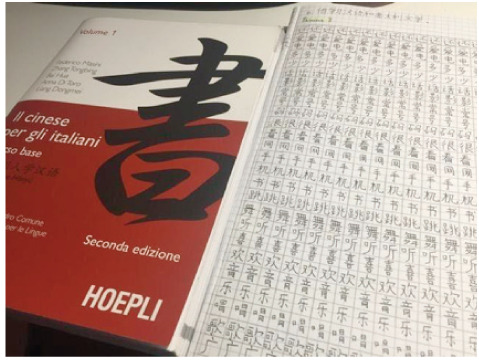

fun intended as a personal pleasure (Figure 1);

fun with the family (Figure 2);

fun as an openness to others (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Personal pleasure

Figure 2.

Fun with the family

Figure 3.

Fun as an openness to others

In the images of the different areas, the theme of fun intended as personal pleasure often appears.

The user’s first comment referring to this photo was: “It’s my motorbike, my Hornet, my very first motorbike, it’s still a bomb, yes yes!” And then again “Eh ... look what a beautiful sun there in the photo.” Undoubtedly it evokes in the user a feeling of fun and pleasure, of happy moments that he tries to carve out at least once a week “To dedicate at least one day a week, Sunday when I’m free, it’s important to have one of those photos there, that is to have fun to be ready to start a ... the start of the week with the charge, ready to go”. When we showed this image to the operator, she was pleasantly satisfied as, in her opinion, it perfectly represents the fun according to the user “The bike at 100% ...” and subsequently referring to all the photographs of the ‘area of entertainment said: “...he is someone who loves to try everything, not only as a sport but also intellectually”

When the photograph of the Christmas decoration was shown, the user said: “It’s a day of celebration and when I’m in a good mood I can feel that life is a precious gift.” And then “Now that Christmas ... a sense of family that, I don’t have a sense of family in my home, but I would like it very much”. With this photograph, a symbol of Christmas, the user tries to remember the funny moments spent together with his family, moments that are not always easy to find but that represent an important memory. However, when the same photograph was shown to the operator, she felt a sense of disorientation as she reports that conflicts between members appear during family celebrations: “mmm ... [short pause] Yes, this also leaves me a bit ... because ... mmm ... that is, I know that Christmas is lived in the family ... that is, let’s say that being the family party sometimes conflict emerge..”.

This image represents a book to learn Chinese and the user states that: “... I think that the language is a barrier that can be “dismantled “through knowledge and precisely after having done this series of studies during the high-school eh, it’s nice to be able to understand a text in the original language too.” and then again “This photo represents my “recent” passion, let’s say, that is to study Chinese as a self-taught person. [Smiles] “.

The user experiences her enjoyment through passions in fact he also states: “... I enjoyed associating these topics with the passions of my life, let’s say.”

The reference operator found that this photograph fully reflects the consideration of the user’s enjoyment: “she is also interested in other languages, so ... yes, yes. She wanted to attend these courses... so yes, yes ... “.

Time

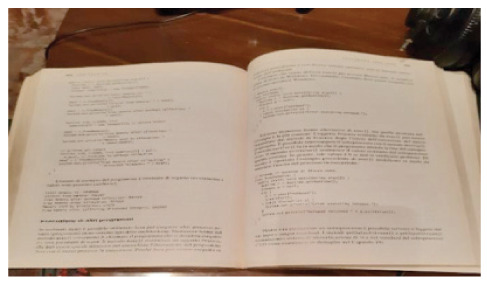

In this area the theme of study and the relationship with books often appeared (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Time to study

The user’s first comment on this photo was “It’s a disappointment” referring to the fact that he is unable to dedicate the time he would like to it. “I haven’t read for a while because I can’t concentrate either at home or in the library..”. The user in his initial presentation told of having attended several schools and universities so he certainly had a strong relationship with books. Through this image he also talked about relational difficulties “... that is, I don’t go to the library anymore, I don’t go there anymore for a variety of reasons, because ... because now I find it hard to be around people ...” and of the fact that “... I am working on it with the therapist ...” in order to one day go back to a library to study.

When the image was shown to the operator, he described a cultured person who used his knowledge to manage the disease. Then the desire to study led him to stop therapy “... so the time spent on books, study, trying to get a degree like this is so much discouraging from a drug therapy...”. Subsequently the operator talked about the relationship between the user and the time of the study “... the time that has gone on books, libraries and these things here is so much and has an ambivalent meaning, because it is also time that has not always been used well ...[in relation to the disease]”,

The description of the image by the user does not express the malaise related to the study, as is evident from the operator’s narration. Like they’re telling the two sides of the same coin.

With this image the user used symbolism to talk about her perception of time “... have time to find my style and mmm and understand how I am made...”. We return to a theme already found in a previous photo, the care of herself that passes through the hygiene of the person and her clothing to feel accepted by others “... it is always a symbolic photo that represents the care I would like to have of my person and even if... I am neglected, but as I would like to take care of myself, spend my time taking care of myself.”. She later entered into a sphere more intimate”... and understand how I’m made... little clothes, I do not say that they represent, but having a style can also help.”, and then talk about the relationship with others (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Take time for yourself!

In the photo of the t-shirt the operator found the symbolism of an earlier photo in which a bottle of perfume appeared and brings it back to a concept of daily care of one’s person “... I could see it in the sense of taking care of one’s clothing every day that is, therefore, like perfume ...”. The operator said that the user when she is not well does not take care of herself, so the t-shirt and the perfume express “... self-care in her daily life which for her is an index of well-being ...”. The photo expresses a daily action that leads to an expression of psychological well-being.

In this image the user affirmed “... it’s a symbolic photo” (Figure 6). When the interviewer asks why she put it in the “perception of time” area, she explains that the biggest gift a person can give is time. Then through the symbol of the gift comes to a transmitted affectivity “... the time that a person gives you, chooses to give to you...”.

Figure 6.

Time as a gift

When we showed the operator the image, not guessing a symbolism related to the images of the gift box.

Something indispensable

In the area of indispensable things, three photos were selected, representative of the inner state of the patients recruited for the research, who immortalized objects considered as indispensable things:

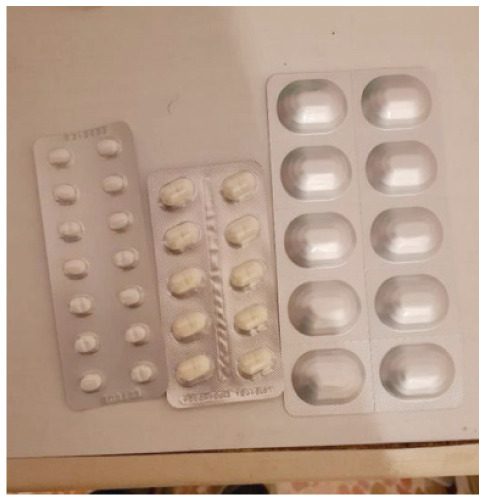

Pharmacological therapies to avoid relapses (Figure 7);

Figure 7.

Pharmacological therapies to avoid relapses

Family Bond (Figure 8);

Figure 8.

Family bond

Dark glasses as a filter to the world (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Dark glasses as a filter to the world

The first pic represents for our patient a mean to no longer have relapses: “drugs are indispensable, because I do not want to have another relapse in my life...”, it is having been defined that in the past he has had repercussions caused by the interruption of drug therapy intake. The interviewer asks if having no relapses indicates: “... I want to feel good that means?” and he replies “yes, yes, I don’t want to be hospitalized.”

Also in his initial presentation he had talked about relapses and therapies: “... I tried several drugs but they weren’t good...” and speaks of extreme gestures: “... several suicide attempts...” and cares through drugs and interviews with therapist “... a therapist... is giving me a big help...”. His concept of well-being is represented by a pharmacological and relational aspect.

Showing the photo to the reference operator, we received a reaction of satisfaction: “I am pleased, I am pleased that he recovers the drugs ...”, he says, in fact, that the patient has previously been discontinuous in taking pharmacological therapies: “... so much so that he always suspended them...”. Also in the initial presentation the operator describes the difficulties: “there was a bit to be fought with regard to pharmacological adherence ...” and relapses: “... he stopped the drug and was sick again...”.

He hypothesizes that the reason that led him to consider drugs as an indispensable part of his life, depends on the creation of a relationship of trust with physician: “... indispensable for life also because of the trust it has in operators... rather than the drugs themselves...”.

So both the user and the operator recognize in this image a therapeutic value given by the human and pharmacological relationship.

In the second photo we find two mugs representing two characters from a Walt Disney movie “Beauty and the Beast”. Apparently two unimportant and impersonal objects that however for the patient interviewed have an extreme and profound value because they represent the bond with her sister. The interviewee’s view of interpersonal relationships is clear: “these are two cups that I bought for myself and my sister, because of course I could not put my sister [in the picture] and so I put the two cups”.

It was difficult to understand the meaning of the photo, at first, for the operator. Later, with the help of the researcher who revealed the meaning of symbolism, immediately understood and confirmed how much she cared about their relationship with the sister.

The third photograph shows an object with a high symbolic value, the photo of the image captured by the patient, in fact, depicts a pair of sunglasses. The interviewee explains: “... represents my way of seeing life, observing without anyone entering my world because... it is said that the eyes are the mirror of the soul and for this reason I am afraid that others may also get there ...”. In addition, he added: “... that I am a mirror of the soul and I am afraid that they may look into me... because I don’t like them... however at the same time you can observe others without they ... they notice it, but without the direct look let’s say... I’d like to meet new people.”

The operator who follows her, during the interview, tells us that she knows this need very well: “... uses them as a screen, to defend herself... so as not to feel invading... observed.” The girl takes them even on bad days, sometimes even indoors.

Place where I feel good

The users were asked to photograph “a place where you are fine”, and three photographs were selected from all those taken by them. We have not given any particular indications for this issue, so users have had ample room for work.

The themes that address the three selected photographs, and which have been considered more significant and transversal to all users, are:

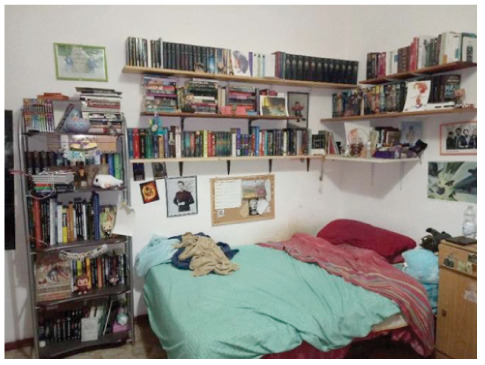

a safe place (Figure 10);

a place that evokes serenity (Figure 11);

a place in the open air (Figure 12).

Figure 10.

A safe place

Figure 11.

A place that evokes serenity

Figure 12.

A place in the open air

The selected photo, belonging to user 3 (U3), depicts the corner of a one-bedroom room where the bed and shelves above it are clearly visible full of books and personal objects.

The user who took this photograph wanted to represent a place where she feels comfortable, a place that expresses safety, a kind of “comfort zone... staying outside makes me uncomfortable so when I get home I’m better off and I’m always there. In other parts of the house I’m not there so they’re places where I feel pretty safe and comfortable.” With this phrase the user wanted to emphasize the need to “return” to a safe place such as her bedroom, since the external environment is a source of discomfort for her.

Analysing the various photographs taken by users for the area “a place where I am well” it emerged that the bedroom (or only the bed) is a recurring subject in all five cases analysed and interviewed; on the part of all five users emerged the need to photograph a comfortable and safe corner of their home, for all represented by the bedroom especially as a source of privacy and relaxation.

User operator 3 interpreted the photograph shown with apparent simplicity, centring the theme that the user wanted to express: “Yes it seems a bit like the lair of imagination in short. Where she gets lost, fantastic a lot, she builds these parallel stories.”

The second selected photo represents the interior of a church by day, whose naves are completely deserted and no people appear.

User 1 (U1) chose to take this photograph as for him the church evokes peace and serenity: “... just enter the church of Reggio, with all the chaos that there is, especially on Fridays when there is market, so, I enter there, a silence of Our Lady ... a silence... and there I sit, don’t please, I sit down and I’m just looking...”. The church itself as a place of worship is taken into account not only as a religious element (“... a place where I am well is any church, because I am a believer, not a practitioner, I am not who knows what fanatic...”), but rather as a place that expresses its spiritual dimension through its need for silence and solitude, which evokes serenity and peace. The theme expressed by this photograph is transversal to other users: all respondents have photographed places, although not religious, that generally express tranquillity. The need for users to find a moment of peace emerges, which can be found in a quiet place, to make full contact with themselves and detach themselves from a “frenetic” dimension as everyday life can be.

The operator interviewed, seeing the photograph, investigated more than anything else the religious dimension of the photograph, linking it to periods when the user was not psychically compensated and his psychosis was expressed with mystical-religious delirium.

The selected photo was taken by user #4: she explains that in general she likes to stay in the middle of greenery, take walks, especially sharing them with her boyfriend. “... it gave me a feeling of freedom, where maybe time can be stopped since it is a place where we are well and maybe appreciate, I do not know, as mentioned before the wonders of the world, of creation”. Here emerges a deeper emotional meaning: even user 5 shows the bond that tends to look in open places intended as a link to nature: “Here we talk about a park, we talk about greenery, nature... although there is a lot of smog here in Emilia with us, it is always nice to stay in the middle of the greenery.”

Other users have associated the place in the open air especially to represent a place to carry out pleasant activities, such as walking with the dog or playing football.

The operator who was interviewed about the selected photo was puzzled about the user’s choice, as he reports that he would not have imagined that he would take so many photos outside, focusing instead on people and affections.

Conclusions

The field research, as well as the analysis of the collected material, has given rise to some considerations and food for thought. First of all, compared to what emerged from the interviews with users, visual techniques in the psychiatric field seem to have been perceived as useful, as they allow the user to use a new, more direct language, in order to be able to communicate his emotion, which is sometimes expressed through a mimesis of reality and /or symbolism. The healthcare professionals involved also confirm the potential of this tool which, when combined with the traditional interview, is able to deepen the patient’s knowledge by overcoming the verbal barriers that often make it difficult to reconstruct the individual experience of illness (32).

Our results suggest that a photo-voice method offers a useful lens from which to examine experiences associated with living with a psychotic disorder, in accordance with another study (4,24,33).

In addition, the data collected through the interviews show that the proposed experience (joint use of two visual techniques) has been considered positive by both users and operators. To probe the perception of usefulness of the techniques, at the end of each individual interview, it was asked to tell the emotional and cognitive load present in the use of this communication methodology.

According to many users, images manage to “focus” on aspects that are difficult to argument and allow, at the same time, to ensure the right time of content processing (an aspect often overlooked during verbal interactions). In accordance with the study of Balbale et al. the application of photovoice enables participants to use photography to document their needs, experiences and perceptions (34).

Through the photos the illness - that is, the subjective feelings related to the condition of illness - finds the right space to be able to express itself without neglecting details. Similarly, the disease - i.e. the pathological aspect objectively detectable in medicine - is reconsidered by the same operators who can expand the set of tools available (including the most traditional psychiatric interview) in order to more fully organize the therapeutic path. In essence, and on the basis of the opinions of the operators involved, the use of visual techniques is able to bring together more elements that manage to highlight aspects otherwise submerged; more generally, in the awareness of limits and variables (such as the smallness of the enlisted sample, predefined timing, variables associated with the clinic) this study has been configured as a creative exploratory mode to look at the subjective experience of young individuals suffering from psychosis.

In accordance with other studies, our research suggests that the use of methods that involve patients and healthcare professionals can be helpful to evaluate and improve healthcare (34-36).

The issues related to daily life that have guided the use of VTs, free from the most usual purely anamnestic aspects of investigation aimed at investigating the symptomatology of their disease, were taken into account by the users interviewed with a high interest. The data collected in this study, therefore, can be useful for the construction of future therapeutic-rehabilitation projects, considering patients suffering from psychosis it is difficult to think about the future by putting in place more intimate and personal aspects and ambitions. The images taken and their explanations can make a contribution to the operators to build together with the person in care an individualized path in a “sartorial” way (37), “in small steps”, for overcoming the limits dictated by the disease, starting from their passions, their desires and characteristics that emerged through the use of self-photography and narration. Finally, this methodology, as suggested by the literature, favours the partnership among service users and providers in mental health services (38).

Conflict of Interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article

References

- Jones DR, Macias C, Barreira PJ, Fisher WH, Hargreaves WA, Harding CM. Prevalence, severity, and co-occurrence of chronic physical health problems of persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(11):1250–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.11.1250. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.11.1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo R, Ferri P, Cameli M, Rovesti S, Piemonte C. Effectiveness of 1-year treatment with long-acting formulation of aripiprazole, haloperidol, or paliperidone in patients with schizophrenia: retrospective study in a real-world clinical setting. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:183–98. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S189245. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S189245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo R, Perrone D, Montorsi A, Balducci J, Rovesti S, Ferri P. Attitude Towards Drug Therapy in a Community Mental Health Center Evaluated by the Drug Attitude Inventory. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:995–1010. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S251993. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S251993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming J, Mahoney J, Carlson E, Engebretson J. An ethnographic approach to interpreting a mental illness photovoice exhibit. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2009;23(1):16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2008.02.008. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pink S. Doing visual ethnography. London: Sage Publication; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Faccioli P, Losacco P. Manuale di sociologia visuale. Miano: Franco Angeli; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Noland CM. Auto-Photography as Research Practice: Identity and Self-Esteem Research. Journal of Research Practice. 2006;2(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Chiozzi P. Saper vedere: il “giro lungo” dell’antropologia visuale. SocietàMutamentoPolitica. 2016;7(14):267–92. doi: 10.13128/SMP-19706. [Google Scholar]

- Somaini A, Pinotti A. Cultura visuale. Immagini sguardi media dispositivi. Milano: Piccola Biblioteca Einaudi; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Frith H, Harcourt D. Using photographs to capture Women’s experiences of chemotherapy: reflecting on the method. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(10):1340–50. doi: 10.1177/1049732307308949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson AJ, Brennan C, House AO. Using photo-elicitation to understand reasons for repeated self-harm: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):98. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1681-3. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1681-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci S, Morris R, Berry K, et al. Early Psychosis Service User Views on Digital Technology: Qualitative Analysis. JMIR Ment Health. 2018;5(4):e10091. doi: 10.2196/10091. doi: 10.2196/10091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart T. Visual Methods of Social Research. Visual Anthropology. 2008;22:80–1. [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa LJ, Nicasio A, Whitley R. Picturing recovery: a photovoice exploration of recovery dimensions among people with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(9):837–42. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200503. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser J. FotoTerapia: tecniche e strumenti per la clinica e gli interventi sul campo. Milano: Franco Angeli; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Burrows A, Schumacher I. Portraits of the Insane: the case of Dr. Diamond. London: Quartet Books; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Weiser J. Using photographs in art therapy practices around the world: Photo therapy, photo-art-therapy, and therapeutic photography. Fusion. 2010;2(3):18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Oster GD, Gould P. Using drawings in assessment and therapy: a guide for mental health professionals. New York: Brunner-Routledge; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Craddick RA. The self-image in the Draw-a-Person test and self-portrait drawings. Journal of Projective Techniques and Personality Assessment. 1963;27(3):288–91. doi: 10.1080/0091651x.1963.10120049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attard A, Larkin M. Art therapy for people with psychosis: a narrative review of the literature. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(11):1067–78. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30146-8. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junne F, Zipfel S. The art of healing: art therapy in the mental health realm. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(11):1006–7. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30210-3. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuisku K, Haravuori H. Psychiatric visual expression interview in dissociative disorders. Psychiatria Fennica. 2016;47:50–75. [Google Scholar]

- Fenner P, Abdelazim RS, Bräuninger I, Strehlow G, Seifert K. Provision of arts therapies for people with severe mental illness. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2017;30(4):306–11. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000338. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawling KDB. ‘She sits all day in the attitude depicted in the photo’: photography and the psychiatric patient in the late nineteenth century. Med Humanit. 2017;43(2):99–100. doi: 10.1136/medhum-2016-011092. doi: 10.1136/medhum-2016-011092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foote B, Smolin Y, Kaplan M, Legatt ME, Lipschitz D. Prevalence of dissociative disorders in psychiatric outpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):623–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.623. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balmer C, Griffiths F, Dunn J. A review of the issues and challenges involved in using participant-produced photographs in nursing research. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(7):1726–37. doi: 10.1111/jan.12627. doi: 10.1111/jan.12627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurworth R. Photo-interviewing for research. Social Research UPDATE. 2003:40. [Google Scholar]

- Margolis E, Pauwels L. The SAGE handbook of visual research methods. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ciampi M. Fondamenti di Sociologia Visuale. Roma: Bonanno; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Glaw X, Inder K, Kable A, Hazelton M. Visual methodologies in qualitative research: Autophotography and photo elicitation applied to mental health research. International journal of qualitative methods. 2017;16(1) doi: 10.1177/1609406917748215. [Google Scholar]

- Prosser J. Image-based Research. A sourcebook for Qualitative Researchers. London: Routledge; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison B. Seeing health and illness worlds – using visual methodologies in a sociology of health and illness: a methodological review. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2002;24(6):856–72. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.00322. [Google Scholar]

- Upthegrove R, Ives J, Broome MR, Caldwell K, Wood SJ, Oyebode F. Auditory verbal hallucinations in first-episode psychosis: a phenomenological investigation. BJPsych Open. 2016;2(1):88–95. doi: 10.1192/bjpo.bp.115.002303. doi: 10.1192/bjpo.bp.115.002303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbale SN, Locatelli SM, LaVela SL. Through Their Eyes: Lessons Learned Using Participatory Methods in Health Care Quality Improvement Projects. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(10):1382–92. doi: 10.1177/1049732315618386. doi: 10.1177/1049732315618386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittdiel JA, Grumbach K, Selby JV. System-based participatory research in health care: an approach for sustainable translational research and quality improvement. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(3):256–9. doi: 10.1370/afm.1117. doi: 10.1370/afm.1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csipke E, Papoulias C, Vitoratou S, Williams P, Rose D, Wykes T. Design in mind: eliciting service user and frontline staff perspectives on psychiatric ward design through participatory methods. J Ment Health. 2016;25(2):114–21. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2016.1139061. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2016.1139061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslund JA, Aschbrenner KA, Bartels SJ. How people with serious mental illness use smartphones, mobile apps, and social media. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2016;39(4):364–7. doi: 10.1037/prj0000207. doi: 10.1037/prj0000207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang JP, Tse S, Davidson L. The big picture unfolds: Using photovoice to study user participation in mental health services. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2016;62(8):696–707. doi: 10.1177/0020764016675376. doi: 10.1177/0020764016675376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]