Keywords: Cattle, Tetratrichomonas, trichomonad, Tritrichomonas, urogenital

Tritrichomonas foetus is a venereal trichomonad parasite which causes reproductive issues in cattle. No other trichomonads are known to be urogenital pathogens in cattle, but there are several reports of Tetratrichomonas and Pentatrichomonas isolates of unclear origin from the cattle urogenital tract (UGT) in the Americas. This study reports the first case of a non-T. foetus cattle urogenital trichomonad isolate in Europe. Molecular analysis of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) 1-5.8S ribosomal RNA-ITS 2 and 18S ribosomal RNA loci suggest that the isolate is a Tetratrichomonas species from a lineage containing other previously described bull preputial isolates. We identified close sequence similarity between published urogenital and gastrointestinal Tetratrichomonas spp., and this is reviewed alongside further evidence regarding the gastrointestinal origin of non-T. foetus isolates. Routine screening for T. foetus is based on culture and identification by microscopy, and so considering other trichomonad parasites of the bovine UGT is important to avoid misdiagnosis.

Introduction

Tritrichomonas foetus is an important bovine venereal parasite which causes reproductive issues including spontaneous abortion, pyometra and infertility (Dąbrowska et al., 2019), imposing a significant economic burden on the beef and dairy industry (Yule et al., 1989). Tritrichomonas foetus is also a prevalent cause of diarrhoea in cats (Asisi et al., 2008), and is considered to be synonymous with the porcine gut-associated Tritrichomonas suis (Slapeta et al., 2012). Tritrichomonas foetus is a protozoan parasite of the class Tritrichomonadea, which together with Trichomonadea belong to the informal taxonomic group the trichomonads, within the phylum parabasalia (Cepicka et al., 2010; Noda et al., 2012). Tetratrichomonas is a diverse genus within Trichomonadea, which most commonly form symbiotic relationships within the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) of animals including invertebrates, fish, mammals, reptiles, amphibians and birds (Cepicka et al., 2006). The genus was originally defined morphologically with characteristics including an ovoid cell body and four anterior flagella of unequal length (Honigberg, 1963). There have been conflicting reports regarding the monophyly of Tetratrichomonas, with some molecular phylogenies placing Trichomonas, Pentatrichomonas and Trichomonoides as ingroups (Cepicka et al., 2006).

Trichomonads appear to undergo frequent cross-species transmission and transfer to alternative body sites; Pentatrichomonas hominis has been isolated from a wide range of mammals including humans, primates, cats, dogs and bovids (Li et al., 2016; Bastos et al., 2018; Li et al., 2020), and it is thought that the human pathogens Trichomonas tenax and Trichomonas vaginalis arose from cross-species transmission of independent lineages of avian oral parasites to the human mouth and urogenital tract (UGT), respectively (Maritz et al., 2014; Peters et al., 2020). Some reports have suggested a degree of fidelity between Tetratrichomonas and host lineages. For example, Cepicka et al. (2006) identified 16 Tetratrichomonas lineages of which the majority were fairly limited in the taxonomic range of host species. However, Tetratrichomonas spp. are often not limited to a single host, for example, Tetratrichomonas gallinarum has been identified as a pathological agent in a wide range of bird species (Cepicka et al., 2005). Transmission across wider taxonomic ranges are also not unknown, and reports of Tetratrichomonas spp. in the lungs of immunocompetent patients with pulmonary disease (Lin et al., 2019) illustrates the potential importance of Tetratrichomonas zoonosis for human health.

There have been several reports of non-Tt. foetus trichomonads isolated from the bull preputial cavity. Morphological and phylogenetic methods have identified these as P hominis, a Pseudotrichomonas sp. and Tetratrichomonas spp., some of which may correspond to the previously described species Tetratrichomonas buttreyi (Dufernez et al., 2007). The most common method for Tt. foetus diagnosis is in vitro culture of preputial washings, and subsequent examination of cultures by light microscopy (Parker et al., 2003), and so false positives resulting from non-Tt. foetus trichomonads may be an issue (Dufernez et al., 2007).

This study provides an additional report of a Tetratrichomonas sp. isolated from bull preputial washings in the UK, and reviews previous reports on trichomonad species in the bovine UGT.

Materials and methods

Source of isolates

Samples were collected from bulls in the UK during routine screening for parasites, in accordance with the principles defined in the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes. To collect samples, the preputial cavity was washed with 30 mL pre-warmed phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.2). Washings were pelleted by centrifugation at 300 × g for 10 min, suspended in 5 mL PBS and examined for motile protozoa. Parasites were cultured by inoculating 1 mL of the PBS suspension into 10 mL Clausens medium [20 g L−1 Neopeptone, 10 g L−1 Lab Lemco (Oxoid), 5 g L−1 neutralized liver digest (Oxoid) and 20 g L−1 glucose, pH 7.4], supplemented with 200 units mL−1 penicillin, 200 μg mL−1 streptomycin and 1000 units mL−1 polymixin B, overlaid on a solid medium slope prepared by heating 7 mL horse serum at 75°C for 2 h. Cultures were incubated at 37°C for 7 days, and were examined microscopically on days 4 and 7 for motile protozoa. Positive cultures were passaged in fresh media, and 10 mL culture was harvested by centrifugation at 300 × g for 10 min, fixed in 15 mL 100% ethanol and stored at −20°C. No cryopreserved stock of the isolate was generated.

Molecular sequence typing

Genomic DNA was extracted from ethanol-fixed parasite isolates using the DNeasy ultraclean microbial kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Loci for molecular sequence typing were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using generic Taq polymerase (NEB). A region containing the 5.8S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and flanking internal transcribed spacers (ITS) 1 and 2 was amplified using the trichomonad-specific TFR1 and TFR2 primers, and the 18S rRNA gene was amplified using the generic eukaryotic primers Euk 1700 and Euk 1900. Resulting products were cloned into pCR4TOPO using the TOPO TA cloning kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sequences were generated for the inserts from five independent clones by Sanger sequencing (Eurofins) on both strands using the T7 and T3 promoter primers, and additional internal sequencing primers were designed to cover the full length of the 18S rRNA gene for both strands. All primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Phylogenetic analysis

A reference collection of ITS1-5.8S rRNA-ITS2 and 18S rRNA trichomonad sequences were selected from the NCBI RefSeq database (O'Leary et al., 2016) by BLASTn search (Altschul et al., 1990) using the new sequences as a query, and from the literature. Sequences were aligned using Tcoffee (Notredame et al., 2000), gaps and poorly aligned regions were trimmed automatically using trimAl (Capella-Gutiérrez et al., 2009) and resulting alignments were visually inspected for accuracy using Seaview (Gouy et al., 2010). Iqtree (Nguyen et al., 2015; Kalyaanamoorthy et al., 2017) was used to construct maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenies using automatic model selection, and reliability was assessed with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Figures were generated using iTol (Letunic and Bork, 2019). Alignments used to generate phylogenies are available in the Supplementary data (S1, S2 and S3).

Metatranscriptomics data analysis

Sequence data for total RNA metatranscriptomics sequencing of the cattle rumen was downloaded from NCBI's SRA database (Leinonen et al., 2011), selecting a subset of 14 out of a total of 48 available samples for analysis (accessions SRX5208721–SRX5208732 and SRX5229555). SortMeRNA (Kopylova et al., 2012) was used to align the reads to the default reference rRNA database, and aligned reads were searched for parasite sequences by BLASTn (Altschul et al., 1990), collecting only the top hit for each query.

Results

Between 2014 and 2021, preputial samples from 9637 bulls were screened for trichomonads. For only a single sample, from a 1-year-old bull in South West England, motile, trichomonad-like protozoa were isolated. Morphological examination by light microscopy revealed four anterior flagella. Rearing conditions of the bull are likely to have allowed sexual contact with other bulls and cows.

In order to identify the isolate, sequences were generated for five clones for the 18S rRNA and ITS1-5.8S rRNA-ITS2 loci. For the 18S rRNA locus, three unique clonal sequences were generated which shared 99.5–99.7% identity, suggesting a single-species infection. ML analysis of the 18S rRNA locus placed all clone sequences together within Tetratrichomonas with strong bootstrap support (Supplementary Fig. S1).

For the ITS1-5.8S rRNA-ITS2 locus, there were three unique sequences which shared 95.2–99% identity, suggesting some diversity amongst the parasites present. In agreement with the 18S rRNA locus, ML analysis also placed all the isolates together within Tetratrichomonas with moderate bootstrap support (Supplementary Fig. S2). The isolates were also placed in a separate lineage from urogenital Tetratrichomonas isolates from cattle originating from a previous study (accession AF342742).

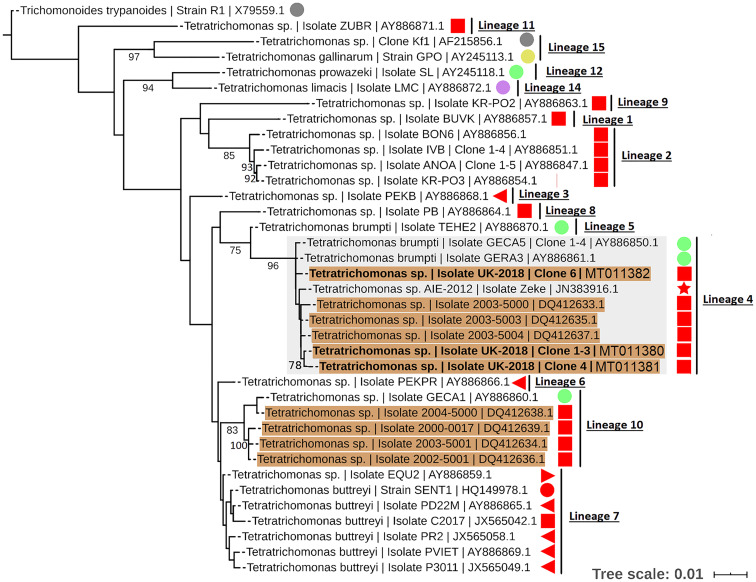

To resolve the Tetratrichomonas lineage of the isolates in more detail, ML analysis was performed on the 18S rRNA sequence from a greater taxonomic sampling of Tetratrichomonas spp., including several bull urogenital isolates from previous studies (Fig. 1). The sequences for all clones grouped within Tetratrichomonas lineage 4 as defined by Cepicka et al. (2006), which includes one group of bull urogenital isolates previously reported (accession DQ412633).

Fig. 1.

ML phylogeny (GTR model with empirical base frequencies, invariable sites and discrete gamma model) for Tetratrichomonas spp. based on the 18S rRNA locus, rooted using Trichomitus batrachorum as an outgroup. Bootstrap values (1000 replicates) >70% are shown on branches. New sequences generated in this study are highlighted in bold. Tetratrichomonas lineages as defined by Cepicka et al. (2006) are annotated, and the lineage of interest is highlighted. Urogenital isolates are highlighted in orange, and host species are annotated with shapes at the tip labels; insect (grey), mollusc (purple), bird (yellow), reptile (green) and mammal (red). Mammals are subdivided into families; bovine (square), porcine (left triangle), equine (right triangle), primate (circle) and anteater (star). Units for tree scale are inferred substitutions per base pair. Genbank (Benson et al., 2015) accessions for each sequence are shown at the end of tip labels.

In order to investigate the potential gastrointestinal origin of urogenital Tetratrichomonas spp. in cattle, we searched published metatranscriptomics data from the cattle rumen for sequences similar to two hypervariable regions (V4 and V8) amongst Tetratrichomonas 18S rRNA sequences. For the published urogenital Tetratrichomonas isolate 2004–5000 (Dufernez et al., 2007; accession DQ412638) we identified sequences identical to the V8 region, and virtually identical (2 base pair mismatch) to the V4 region. BLAST search results were identical in terms of mismatches, gaps and query coverage for 11 out of 14 samples tested. In contrast, we did not identify any sequences of a similarly highly sequence identity to the urogenital Tetratrichomonas sequence generated in this study. Representative BLAST results for a single sample are shown in Supplementary Table S2, and an alignment between metatranscriptome sequences and urogenital Tetratrichomonas 18S rRNA sequences are shown in Supplementary file S4.

In addition to the isolates identified in this study, there have been numerous reports of trichomonads isolated from the UGT of cattle, summarized in Table 1. A total of 151 trichomonad isolates have been reported. With the exception of isolates obtained from this study, all previous isolates originate from the Americas. Various morphological and molecular techniques have assigned the isolates as Tetratrichomonas and Pentatrichomonas spp., which appear to have been isolated in roughly equal proportions. In contrast, there has only been a single report of a Pseudotrichomonas isolate.

Table 1.

Summary of reports of non-Tritrichomonas foetus trichomonads isolated from the cattle UGT

| Reference | Number of isolates | Location | Identification methodsa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dufernez et al. (2007) |

Tetratrichomonas 7 Pentatrichomonas 4 Pseudotrichomonas 1 Total: 12 |

USA | Morphology, PCR, molecular phylogeny |

| Kleina et al. (2004) |

Tetratrichomonas 1 Pentatrichomonas 0 Pseudotrichomonas 0 Total: 1 |

Brazil | Molecular phylogeny |

| Walker et al. (2003) |

Tetratrichomonas 14 Pentatrichomonas 18 Pseudotrichomonas 0 Total: 32 |

USA | Morphology, sequence comparison |

| BonDurant et al. (1999) |

Tetratrichomonas 14 Pentatrichomonas 0 Pseudotrichomonas 0 Total: 14 |

USA | Morphology, PCR |

| Campero et al. (2003) |

Tetratrichomonas NA Pentatrichomonas NA Pseudotrichomonas NA Total: 48 |

Argentina | Morphology, PCR |

| Hayes et al. (2003) |

Tetratrichomonas 16 Pentatrichomonas 21 Pseudotrichomonas 0 Total 37 |

USA | PCR |

| Cobo et al. (2003) |

Tetratrichomonas 6 Pentatrichomonas 0 Pseudotrichomonas 0 Total: 6 |

Argentina | Morphology, PCR |

| Parker et al. (2003) | NA | Canada | Morphology, PCR |

| This study |

Tetratrichomonas 1 Pentatrichomonas 0 Pseudotrichomonas 0 Total: 1 |

UK | Morphology, molecular phylogeny |

| Total |

Tetratrichomonas 59 Pentatrichomonas 43 Pseudotrichomonas 1 Total: 151 |

aPCR and phylogenetic data are based on amplification of the ITS1-5.8S rRNA-ITS2 locus, except for Dufernez et al. (2007) and this study, which also examined the 18S rRNA locus.

Discussion

This study reports the first case of a non-Tt. foetus trichomonad isolated from the bovine UGT in Europe. In agreement with previous reports of cattle urogenital trichomonads (Walker et al., 2003; Kleina et al., 2004; Dufernez et al., 2007), the morphological and sequence data indicate that this isolate is a Tetratrichomonas sp. The phylogenies presented here are largely in agreement with previous studies regarding the interrelationship between trichomonads and the reported lineages of Tetratrichomonas spp. (Cepicka et al., 2006; Dufernez et al., 2007). Similarly to previous reports (Cepicka et al., 2006, 2010), there is discrepancy between phylogenies based on the 18S rRNA and ITS1-5.8S rRNA-ITS2 in terms of the monophyly of the Tetratrichomonas genus.

Our results support the placement of the new isolates in Tetratrichomonas lineage 4 as defined by Cepicka et al. (2006), which corresponds to group B of the bull urogenital Tetratrichomonas isolates defined by Dufernez et al. (2007). The new isolates were distinct from bull urogenital group A (Dufernez et al., 2007), corresponding to Tetratrichomonas lineage 10 (Cepicka et al., 2006) and also possibly the bull urogenital isolates described by Walker et al. (2003), although this is not well resolved. In addition, the ITS1-5.8S rRNA-ITS2 data suggest some genetic diversity amongst the clonal sequences from the new isolate, as the three clones did not cluster together, potentially indicating a non-clonal infection or heterogeneity amongst multi-copy rRNA genes (Torres-Machorro et al., 2010). These observations overall suggest a degree of genetic heterogeneity amongst cattle urogenital Tetratrichomonas isolates.

Tetratrichomonas lineage 4 was described as mostly limited to the tortoise GIT (Cepicka et al., 2006). This lineage has also been found in mammals, but excluding the cattle isolates, all others including the elephant isolate SLON (Cepicka et al., 2006) and the anteater isolate Zeke (Ibañez-Escribano et al., 2013), originate from zoo animals which may suggest an artificial context for transmission. Isolates from Tetratrichomonas lineage 10 (Cepicka et al., 2006) have also been found in the bull UGT, and based on morphological data it has been suggested that this corresponds to the previously described cattle gastrointestinal species Te. buttreyi (Dufernez et al., 2007). Intriguingly, Tetratrichomonas lineage 10 also appears to be mostly restricted to tortoises (Cepicka et al., 2006).

At least two Tetratrichomonas lineages, P. hominis, and a Pseudotrichomonas sp. have been isolated from the cattle UGT (Walker et al., 2003; Dufernez et al., 2007). These trichomonad isolates alternatively represent either emerging or established urogenital species or sporadic spillover of microbes from an alternative reservoir, most likely the bovine GIT. The possibility of cross contamination during sample collection should also not be discounted for some isolates. The genetic heterogeneity amongst cattle urogenital isolates may support the spillover hypothesis. This is in contrast to parasite species thought to have emerged through cross-species or cross-mucosa transmission, such as Tt. foetus, which shows a remarkable degree of genetic homogeneity suggestive of a recent founder event (Kleina et al., 2004). Cattle urogenital trichomonad isolation shows a sporadic geographic pattern (Campero et al., 2003; Kleina et al., 2004; Dufernez et al., 2007) which also supports the spillover hypothesis, as the events appear to be unrelated to one another. We identified sequences highly similar to cattle urogenital Tetratrichomonas 18S rRNA (Dufernez et al., 2007) frequently occurring in the cattle rumen metatranscriptome (Li et al., 2019), providing strong evidence that these urogenital isolates are of gastrointestinal origin. The infrequent urogenital detection of non-Tt. foetus trichomonads in a backdrop of frequent Tt. foetus monitoring (Yao, 2013) suggests that the events are rare, although misidentification of other trichomonads as Tt. foetus is also possible.

There are plausible sources for the isolated urogenital trichomonads from the bovine GIT; Tetratrichomonas spp. (Zhang et al., 2020), such as Te. buttreyi (Dufernez et al., 2007), are known to inhabit the cattle gut, and P. hominis is known to occupy the GIT of a very wide range of animals (Li et al., 2016), including cattle (Li et al., 2020). The isolate related to the putatively free-living Pseudotrichomonas keilini (Dufernez et al., 2007) at most represents a very rare event, as only a single isolate has been reported, and so contamination cannot be ruled out. Alternatively, Monoceromonas ruminantium is also relatively closely related (Dufernez et al., 2007) and has been isolated from the GIT of cattle (Hampl et al., 2004), suggesting that the lineage could be host-associated and that P. keilini is an exception or mislabelled as free-living. The presence of gastrointestinal-associated bacteria at the same site as urogenital trichomonad isolation provides further evidence for their gut origin (Cobo et al., 2003). A route of gastrointestinal to urogenital transmission through sexual mounting behaviour, potentially between young bulls, has been suggested (BonDurant et al., 1999).

During experimental inoculation of Tetratrichomonas preputial isolates in the cattle UGT, results have ranged from no persistence (Cobo et al., 2004) to sporadic re-detection up to 2 weeks after inoculation in mature bulls (Cobo et al., 2007b) and no persistence beyond 6 h in young heifers (Cobo et al., 2004, 2007a). Pentatrichomonas hominis derived from the cattle gut also failed to persist in the UGT of heifers (Cobo et al., 2007a). Variation in results is likely due to strain and host differences, however failure of preputial Tetratrichomonas to regularly establish colonization during experimental infection (Cobo et al., 2004, 2007a, 2007b) provides strong evidence for the sporadic origin hypothesis. There was no evidence for pathology caused by any of the non-Tt. foetus trichomonads (Cobo et al., 2004).

Together, the evidence supports the hypothesis that non-Tt. foetus trichomonad isolates obtained from the cattle UGT do not represent an emerging urogenital inhabitant but rather a sporadic transmission from another source, most likely the gut. However, transmission of parasites between these mucosal sites may increase the possibility of new pathogens emerging, as has been documented for other trichomonads (Maritz et al., 2014). The detection of trichomonads in the cattle UGT, and the mosaic pattern of host and mucosal site specialization amongst the trichomonads highlight their adaptability and thus zoonotic potential.

The most significant concern associated with non-Tt. foetus trichomonads in the cattle UGT is most likely misdiagnosis through confusion with Tt. foetus, which could cause unnecessary culling of suspected infected animals (Campero et al., 2003). The scale of misdiagnosis is unclear; the low detection frequency of trichomonads, particularly in regions which are intensely monitored, such as the UK, suggests a low frequency. However, detection rates were as high as 8.5% in some groups of bulls (Campero et al., 2003), suggesting the issue may be more significant in some regions. The most common method of Tt. foetus monitoring is culture-based isolation and morphological identification by light microscopy (Parker et al., 2003) which may lack specificity because expertise to differentiate trichomonads based on morphology is rare (Dufernez et al., 2007). Molecular detection methods offer the advantages of improved speed and specificity (Felleisen, 1997; Hayes et al., 2003; Parker et al., 2003) and enhanced sensitivity compared with culture-based detection (Cobo et al., 2007b), without the need for morphological expertise. However, molecular methods are not routinely used due to high cost and impracticality in an agricultural setting. Lower cost molecular methods such as loop-assisted isothermal amplification have been applied to achieve very sensitive and specific Tt. foetus detection (Oyhenart et al., 2013) and so may offer a more practical solution. As evidence suggests Tetratrichomonas sp. are short-lived in the bull UGT (Cobo et al., 2004, 2007b), and may originate from sexual mounting behaviour (Walker et al., 2003), separating bulls before testing may also reduce misdiagnosis. Artificial insemination combined with regular monitoring of semen for parasites has proven a very successful control method (Dąbrowska et al., 2019), and should also be considered for more widespread adoption.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of Alan Murphy in collecting metadata for the animal included in this study.

Author contributions

E. V. R. collected the original isolate. N. P. B. performed the molecular sequence typing, data analysis and wrote the article. R. P. H. contributed to project design and feedback, amendments and advice for writing the article.

Financial support

This study was supported by the Biotechnology and Bioscience Research Council Doctoral Training Partnership for Newcastle, Liverpool and Durham (NPB, RH, grant number: BB/M011186/1) and the Animal and Plant Health Agency (EVR).

Ethical standards

No animals were used for experimental procedures to complete this work. The animal was sampled as part of routine, statutory sampling for bulls used in artificial insemination, as required by The Bovine Semen (England) Regulations (2007).

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S003118202100086X.

click here to view supplementary material

Data

All sequences generated in this study can be obtained from the NCBI Genbank database (Benson et al., 2015) under accessions MT011380-MT011382 for the 18S rRNA sequences and MT375127-MT375129 for the ITS1-5.8S rRNA-ITS2 sequences.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW and Lipman DJ (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology 215, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asisi N, Steiner JM, Pfister K and Kohn B (2008) Tritrichomonas foetus – a cause of diarrhoea in cats. Kleintierpraxis 53, 688. [Google Scholar]

- Bastos BF, Brener B, de Figueiredo MA, Leles D and Mendes-de-Almeida F (2018) Pentatrichomonas hominis infection in two domestic cats with chronic diarrhea. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery Open Reports 4, 1–4. doi: 10.1177/2055116918774959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson DA, Clark K, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J and Sayers EW (2015) GenBank. Nucleic Acids Research 43, D30–D35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BonDurant RH, Gajadhar A, Campero CM, Johnson E, Lun Z-R, Nordhausen RW, Van Hoosear KA, Villanueva MR and Walker RL (1999) Preliminary characterization of a Tritrichomonas foetus-like protozoan isolated from preputial smegma of virgin bulls. The Bovine Practitioner 33, 124–127. [Google Scholar]

- Campero CM, Rodriguez Dubra C, Bolondi A, Cacciato C, Cobo E, Perez S, Odeon A, Cipolla A and BonDurant RH (2003) Two-step (culture and PCR) diagnostic approach for differentiation of non-T. foetus trichomonads from genitalia of virgin beef bulls in Argentina. Veterinary Parasitology 112, 167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capella-Gutiérrez S, Silla-Martínez JM and Gabaldón T (2009) trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 25, 1972–1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepicka I, Kutigova K, Tachezy J, Kulda J and Flegr J (2005) Cryptic species within the Tetratrichomonas gallinarum species complex revealed by molecular polymorphism. Veterinary Parasitology 128, 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepicka I, Hampl V, Kulda J and Flegr J (2006) New evolutionary lineages, unexpected diversity, and host specificity in the parabasalid genus Tetratrichomonas. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 39, 542–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepicka I, Hampl V and Kulda J (2010) Critical taxonomic revision of parabasalids with description of one new genus and three new Species. Protist 161, 400–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobo ER, Campero CM, Mariante RM and Benchimol M (2003) Ultrastructural study of a tetratrichomonad species isolated from prepucial smegma of virgin bulls. Veterinary Parasitology 117, 195–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobo ER, Cantón G, Morrell E, Cano D and Campero CM (2004) Failure to establish infection with Tetratrichomonas sp. in the reproductive tracts of heifers and bulls. Veterinary Parasitology 120, 145–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobo ER, Corbeil LB, Agnew DW, VanHoosear K, Friend A, Olesen DR and BonDurant RH (2007a) Tetratrichomonas spp. and Pentatrichomonas hominis are not persistently detectable after intravaginal inoculation of estrous heifers. Veterinary Parasitology 150, 18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobo ER, Favetto PH, Lane VM, Friend A, VanHooser K, Mitchell J and BonDurant RH (2007b) Sensitivity and specificity of culture and PCR of smegma samples of bulls experimentally infected with Tritrichomonas foetus. Theriogenology 68, 853–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dąbrowska J, Karamon J, Kochanowski M, Sroka J, Zdybel J and Cencek T (2019) As a causative agent of Tritrichomonosis in different animal hosts. Journal of Veterinary Research 63, 533–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufernez F, Walker RL, Noël C, Caby S, Mantini C, Delgado-Viscogliosi P, Ohkuma M, Kudo T, Capron M, Pierce RJ, Villanueva MR and Viscogliosi E (2007) Morphological and molecular identification of non-Tritrichomonas foetus trichomonad protozoa from the bovine preputial cavity. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 54, 161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felleisen RS (1997) Comparative sequence analysis of 5.8S rRNA genes and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions of trichomonadid protozoa. Parasitology 115, 111–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouy M, Guindon S and Gascuel O (2010) SeaView version 4: a multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Molecular Biology and Evolution 27, 221–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampl V, Cepicka I, Flegr J, Tachezy J and Kulda J (2004) Critical analysis of the topology and rooting of the parabasalian 16S rRNA tree. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 32, 711–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes DC, Anderson RR and Walker RL (2003) Identification of trichomonadid protozoa from the bovine preputial cavity by polymerase chain reaction and restriction fragment length polymorphism typing. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 15, 390–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honigberg BM (1963) Evolutionary and systematic relationships in the flagellate order Trichomonadida Kirby. Journal of Protozoology 10, 20–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibañez-Escribano A, Nogal-Ruiz JJ, Delclaux M, Martinez-Nevado E and Ponce-Gordo F (2013) Morphological and molecular identification of Tetratrichomonas flagellates from the giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla). Research in Veterinary Science 95, 176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh BQ, Wong TKF, von Haeseler A and Jermiin LS (2017) ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nature Methods 14, 587–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleina P, Bettim-Bandinelli J, Bonatto SL, Benchimol M and Bogo MR (2004) Molecular phylogeny of Trichomonadidae family inferred from ITS-1, 5.8S rRNA and ITS-2 sequences. International Journal for Parasitology 34, 963–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopylova E, Noé L and Touzet H (2012) SortMeRNA: fast and accurate filtering of ribosomal RNAs in metatranscriptomic data. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 28, 3211–3217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinonen R, Sugawara H, Shumway M and Collaboration INSD (2011) The sequence read archive. Nucleic Acids Research 39, D19–D21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I and Bork P (2019) Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v4: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Research 47, W256–W259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WC, Ying M, Gong PT, Li JH, Yang J, Li H and Zhang XC (2016) Pentatrichomonas hominis: prevalence and molecular characterization in humans, dogs, and monkeys in Northern China. Parasitology Research 115, 569–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Hitch TCA, Chen Y, Creevey CJ and Guan LL (2019) Comparative metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analyses reveal the breed effect on the rumen microbiome and its associations with feed efficiency in beef cattle. Microbiome 7, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WC, Huang JM, Fang Z, Ren Q, Tang L, Kan ZZ, Liu XC and Gu YF (2020) Prevalence of Tetratrichomonas buttreyi and Pentatrichomonas hominis in yellow cattle, dairy cattle, and water buffalo in China. Parasitology Research 119, 637–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Ying F, Lai Y, Li X, Xue X, Zhou T and Hu D (2019) Use of nested PCR for the detection of trichomonads in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. BMC Infectious Diseases 19, 512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maritz JM, Land KM, Carlton JM and Hirt RP (2014) What is the importance of zoonotic trichomonads for human health? Trends in Parasitology 30, 333–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A and Minh BQ (2015) IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution 32, 268–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda S, Mantini C, Meloni D, Inoue J, Kitade O, Viscogliosi E and Ohkuma M (2012) Molecular phylogeny and evolution of parabasalia with improved taxon sampling and new protein markers of actin and elongation factor-1α. PLoS One 7, e29938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notredame C, Higgins DG and Heringa J (2000) T-Coffee: a novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. Journal of Molecular Biology 302, 205–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary NA, Wright MW, Brister JR, Ciufo S, Haddad D, McVeigh R, Rajput B, Robbertse B, Smith-White B, Ako-Adjei D, Astashyn A, Badretdin A, Bao Y, Blinkova O, Brover V, Chetvernin V, Choi J, Cox E, Ermolaeva O, Farrell CM, Goldfarb T, Gupta T, Haft D, Hatcher E, Hlavina W, Joardar VS, Kodali VK, Li W, Maglott D, Masterson P, McGarvey KM, Murphy MR, O'Neill K, Pujar S, Rangwala SH, Rausch D, Riddick LD, Schoch C, Shkeda A, Storz SS, Sun H, Thibaud-Nissen F, Tolstoy I, Tully RE, Vatsan AR, Wallin C, Webb D, Wu W, Landrum MJ, Kimchi A, Tatusova T, DiCuccio M, Kitts P, Murphy TD and Pruitt KD (2016) Reference sequence (RefSeq) database at NCBI: current status, taxonomic expansion, and functional annotation. Nucleic Acids Research 44, D733–D745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyhenart J, Martínez F, Ramírez R, Fort M and Breccia JD (2013) Loop mediated isothermal amplification of 5.8S rDNA for specific detection of Tritrichomonas foetus. Veterinary Parasitology 193, 59–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker S, Campbell J, McIntosh K and Gajadhar A (2003) Diagnosis of trichomoniasis in ‘virgin’ bulls by culture and polymerase chain reaction. Canadian Veterinary Journal 44, 732–734. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Das S and Raidal SR (2020) Diverse Trichomonas lineages in Australasian pigeons and doves support a columbid origin for the genus Trichomonas. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 143, 106674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slapeta J, Müller N, Stack CM, Walker G, Lew-Tabor A, Tachezy J and Frey CF (2012) Comparative analysis of Tritrichomonas foetus (Riedmüller, 1928) cat genotype, T. foetus (Riedmüller, 1928) cattle genotype and Tritrichomonas suis (Davaine, 1875) at 10 DNA loci. International Journal of Parasitology 42, 1143–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Machorro AL, Hernández R, Cevallos AM and López-Villaseñor I (2010) Ribosomal RNA genes in eukaryotic microorganisms: witnesses of phylogeny? FEMS Microbiology Reviews 34, 59–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker RL, Hayes DC, Sawyer SJ, Nordhausen RW, Van Hoosear KA and BonDurant RH (2003) Comparison of the 5.8S rRNA gene and internal transcribed spacer regions of trichomonadid protozoa recovered from the bovine preputial cavity. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 15, 14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao C (2013) Diagnosis of Tritrichomonas foetus-infected bulls, an ultimate approach to eradicate bovine trichomoniasis in US cattle? Journal of Medical Microbiology 62, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yule A, Skirrow SZ and Bonduran RH (1989) Bovine trichomoniasis. Parasitology Today 5, 373–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Li F, Chen Y, Wu H, Meng Q and Guan LL (2020) Metatranscriptomic profiling reveals the effect of breed on active rumen eukaryotic composition in beef cattle with varied feed efficiency. Frontiers in Microbiology 11, 367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S003118202100086X.

click here to view supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

All sequences generated in this study can be obtained from the NCBI Genbank database (Benson et al., 2015) under accessions MT011380-MT011382 for the 18S rRNA sequences and MT375127-MT375129 for the ITS1-5.8S rRNA-ITS2 sequences.