Abstract

The use of colonoscopies in the screening of colorectal cancers has helped in the early detection and treatment of these cancers. Less than 0.5% of patients develop colonoscopy complications, mostly bleeding, and less frequently, perforations. There have been very few reported cases of micro-perforations following colonoscopies. We present a case of a 66-year-old female smoker who had undergone a screening colonoscopy for colorectal cancer with two polyps removed 3 weeks prior, who was brought to the hospital because of altered mental status and hypotension. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast demonstrated intraabdominal abscess which was drained by interventional radiology. A culture of the pus grew Streptococcus constellatus, a pus-forming bacterium. She was treated with ceftriaxone and metronidazole for a total of 6 weeks, and a repeat CT of abdomen and pelvis demonstrated complete resolution. The only contributing factor to the formation of the intraabdominal abscess was a screening colonoscopy with polypectomy, which might have caused micro-perforations in the colon with the seeding of Streptococcus constellatus. The occurrence of intraabdominal abscess following a colonoscopy is very rare, and requires a high index of suspicion in patients who present with sepsis following colonoscopies.

Keywords: Streptococcus constellatus, Streptococcus anginosus, Streptococcus milleri, Intraabdominal abscess, Colonoscopy, Polypectomy

Introduction

The use of colonoscopy for screening of colorectal cancer is recommended as of age 50 years or even earlier with the presence of certain risk factors [1]. Rare complications have been reported, ranging from those related to sedation, to preparation for the procedure, bleeding, infections, and sometimes perforations. The rate of perforations following a colonoscopy is about 0.5 per 1,000 colonoscopies, but associated with high morbidity and mortality [2, 3]. The treatment of these perforations can either be surgical or non-surgical depending on the type of colonoscopy and the clinical evolution of the patient [4].

Streptococcus constellatus, a streptococcal species belonging to the Streptococcus anginosus or Streptococcus milleri group, is part of the normal flora of the oral cavity, urogenital region and intestines [5]. It is an abscess-forming bacterium which is usually associated with oral, head and neck, and abdominal abscesses. The isolation of Streptococcus milleri from an intraabdominal abscess has been associated with an unrecognized gastrointestinal perforation [6]. In this report, we present a case of a patient who had a diagnostic colonoscopy 3 weeks prior to her admission, and was found to have intraabdominal abscess with culture showing heavy growth of Streptococcus constellatus.

Case Report

Investigations

A 66-year-old female smoker was referred to the emergency department (ED) by her primary care doctor because of hypotension. She had a colonoscopy 3 weeks prior, with removal of two serrated polyps from the descending colon. Two weeks after the procedure, the patient started feeling generalized weakness and fatigue which prompted her to see her primary care doctor, where she was found to have a blood pressure of 60/30 mm Hg and was immediately sent to the ED. The patient was accompanied by her brother to the ED.

On arrival at the ED, the patient was confused and appeared lethargic. Her brother reported that she had a fever for the past 5 days. In the ED she had a temperature of 98.1 °F, blood pressure of 74/45 mm Hg, heart rate of 99 beats/min, and respiratory rate of 18 breaths/min. On physical examination, she was lethargic and confused, unable to answer questions correctly. Her conjunctivae were pink, no signs of jaundice, lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally, and the heart sounds were audible with no murmurs, rubs, or gallops. Abdominal examination revealed diffuse abdominal tenderness as well as bilateral costovertebral angle tenderness. Bowel sounds were present in all four quadrants.

Diagnosis

Laboratory investigations demonstrated a white blood cell (WBC) count of 28,700/mm3 with left shift, and normocytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 8.3 g/dL with liver and renal profiles within the normal physiological ranges. A 2-L intravenous (IV) bolus of normal saline was administered to the patient, which raised her blood pressure to 105/60 mm Hg. Blood and urine cultures were obtained, she was started on ceftriaxone for the treatment of possible pyelonephritis and was transferred to the medical intensive care unit for further management.

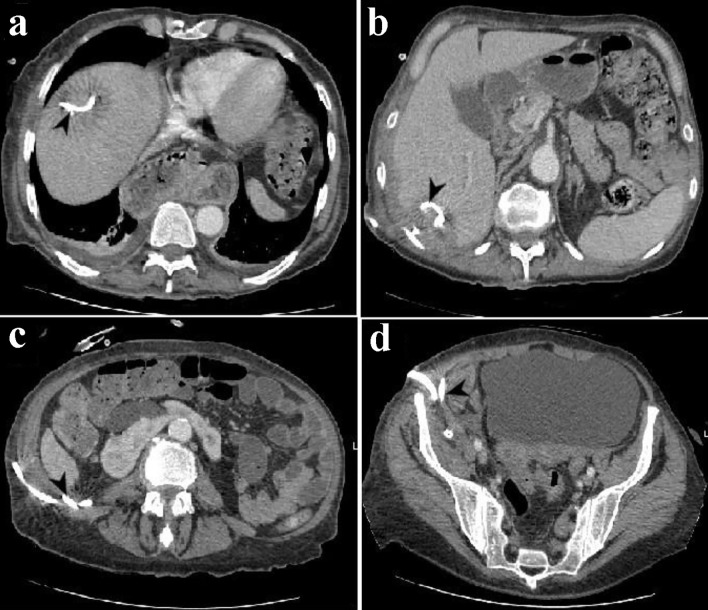

A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis was performed which revealed multiple hepatic and perihepatic fluid collections, suspicious of abscesses, with extension under the 12th rib and the lower right flank. Another loculated fluid collection was seen in the right lower quadrant and other smaller fluid collections were also noted to be present (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

CT of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast showing intraabdominal abscess. (a) Arrowhead shows loculated fluid collection, with enhancing walls, in the anterior segment of the right lobe at the hepatic dome. (b) Arrowhead shows an ovoid thick-walled fluid collection in the posterior segment of the right hepatic lobe. (c) Arrowhead shows a large lobulated fluid collection just lateral to the right colon anteriorly in the right lower quadrant/right pelvis. (d) Arrowhead shows fluid collection posterior right flank, extending into the right paraspinal musculature. CT: computed tomography.

Treatment

Interventional radiology (IR) and surgery were urgently consulted. Four intraabdominal drains were placed by IR, which immediately drained 750 cc of pus which was sent to the laboratory for culture. Ceftriaxone was discontinued and the patient was started on IV meropenem, vancomycin, and metronidazole while awaiting culture and sensitivity results.

On day 3 of admission, the culture of the pus showed a “heavy growth” of Streptococcus constellatus. Due to culture results, meropenem and vancomycin were discontinued and the patient was restarted on ceftriaxone in addition to metronidazole. Marked improvement was observed in the clinical state of the patient as she became more alert, improved appetite, with decreased abdominal tenderness.

Follow-up and outcomes

There was also a marked improvement in her WBC count (Table 1). On day 7 of admission, there was a decrease in the quantity of fluid being drained from the abdomen to less than 10 cc drained per 24-h period. A repeat CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was performed, which revealed a marked decrease in the intraabdominal abscess with a small residual collection, 2 cm in size, located in the segment 4a of the liver. All the other areas of fluid collections noted on the previous CT scan showed complete drainage with no significant residual fluid (Fig. 2). With this result, three out of the four drains were removed. The drain in the dome of the liver was left in place as it was still draining residual purulent fluid. On day 14 of admission, the last drain was removed, and a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) was placed for the patient to receive the antibiotics for a total of 6 weeks. The patient was discharged the following day to a nursing home to follow up as outpatient.

Table 1. Laboratory Values During Admission.

| Days of admission |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 14 | |

| WBC (103/µL) (NV: 4.0 - 11.2) | 28.7 | 25.1 | 24.7 | 15.9 | 10.5 | 10.1 | 12.4 | 11.2 | 10.7 | 10.0 | 10.2 |

| Neutrophils (%) (NV: 30 - 71) | 93.2 | 93.1 | 94.8 | 89.0 | 74.4 | 68.4 | 73.3 | 70.1 | 70.3 | 67.2 | 67.8 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) (NV: 13.7 - 17.5) | 8.3 | 8.0 | 8.1 | 9.0 | 8.8 | 9.2 | 9.6 | 9.8 | 9.5 | 9.7 | 9.2 |

| Platelet (103/µL) (NV: 150 - 400) | 711 | 550 | 497 | 614 | 567 | 550 | 609 | 555 | 500 | 463 | 441 |

| BUN (mg/dL) (NV: 7 - 18) | 16 | 14 | 13 | 11 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 11 | 14 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) (NV: 0.7 - 1.3) | 1.6 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.2 |

WBC: white blood cell; NV: normal value; BUN: blood urea nitrogen.

Figure 2.

CT of the abdomen and pelvis showing the four percutaneous drains. (a) Arrowhead shows a percutaneous drain in the right hepatic dome. (b) Arrowhead shows a percutaneous drain in the tip of the right hepatic lobe. (c) Arrowhead shows a percutaneous drain in the right paracolic gutter. (d) Arrowhead shows a percutaneous drain in the right lower quadrant. CT: computed tomography.

A repeat of CT of abdomen and pelvis 4 weeks later revealed complete resolution of the abscesses.

Discussion

Colonoscopy is used both for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. A major diagnostic indication is for screening or surveillance of colon cancer, where it is considered a gold standard [1]. Age of screening depends on the patient’s medical and family history, but usually starts as from 50 years of age in patients with no medical or family history. Visible lesions seen during the procedure are sampled or removed [7]. The risk of complications following colonoscopies are very low, with serious harm occurring in 2.8 per 1,000 cases [8], and mostly after polyp removal and related to the age of the patient. These complications include perforations (0.5 per 1,000 colonoscopies), post-colonoscopy bleeding (2.6 per 1,000 colonoscopies) and death (2.9 per 100,000 colonoscopies) [2].

Perforations usually occur either by mechanical trauma from the colonoscope, barotrauma from the pressure exerted by the colonoscope, or following injury during polypectomy. Our patient is a 66-year-old female who had a screening colonoscopy with polyp removal 3 weeks prior to her admission. The discovery of intraabdominal abscess on admission was very unexpected and often requires a high level of suspicion. The only predisposing factor for this was the colonoscopy which was performed 3 weeks prior. The identification of Streptococcus constellatus in an intraabdominal abscess is usually associated with an unrecognized gastrointestinal perforation [6]. The patient must have had a perforation, or micro-perforation during the colonoscopy which went unnoticed, and might have led to seeding of the pus forming bacteria, Streptococcus constellatus, hence the intraabdominal abscess formation. The patient had a polypectomy on the descending colon and the abscess was mostly on the right side. Even though polypectomy multiplies the risk of perforations, there might have been some perforations on the ascending colon or right half of the transverse colon as a result of the passage of the scope or barotrauma. It is unclear if the seeding bacteria came from the polypectomy site or another site which was more to the right during the procedure.

The clinical presentation of intraabdominal abscesses is variable. Patients may present with fever, anorexia, abdominal pain, tachycardia, tachypnea, oliguria, and dehydration. Retroperitoneal abscesses or abscesses that are located deep in the pelvis, may present with no clinical signs. If the presentation is delayed, patients may develop septic shock [9]. Our patient came in with hypotension which got better with fluid challenge. Due to suspicion of an acute abdomen, a CT of the abdomen with contrast was done which revealed the presence of the abscess.

The treatment options could either be surgical or conservative, depending on the clinical state of the patient and the imaging exams. Broad spectrum antibiotics are usually initiated while awaiting culture and sensitivity results [10, 11]. Streptococcus constellatus has been found to be largely susceptible to penicillin, ampicillin, and ceftriaxone. Metronidazole has also been shown to be effective in the treatment of infections caused by this organism. In addition to appropriate antimicrobial treatment, effective drainage is also required, which can be performed through the percutaneous or the open surgical approach. The open surgical approach may be employed if the percutaneous drainage fails [10]. Our patient was treated with metronidazole and ceftriaxone, and also had the abscess drained percutaneously by IR.

There is very limited number of cases reported so far of intra-abdominal abscesses following colonoscopies. Physicians need to maintain a high index of suspicion in patients who present with sepsis following colonoscopy.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates the possibility of developing intraabdominal abscess following colonoscopy, and further validates the association between Streptococcus constellatus and intraabdominal abscess formation. There are very few reported cases on intraabdominal abscess after colonoscopy. Therefore, physicians should always maintain a high index of suspicion in patients who present with sepsis following a colonoscopy.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

F. Atemnkeng collected the data, guided the literature search, wrote the manuscript, and is the research guarantor. A. Al-Tkrit, S. David, H. Alataby, and A. Nagaraj helped with the data collection and writing of the article. K. Diaz and J. Nfonoyim reviewed and supervised the study.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

- 1.Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, Pike IM, Adler DG, Fennerty MB, Lieb JG 2nd. et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81(1):31–53. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reumkens A, Rondagh EJ, Bakker CM, Winkens B, Masclee AA, Sanduleanu S. Post-colonoscopy complications: a systematic review, time trends, and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(8):1092–1101. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chukmaitov A, Bradley CJ, Dahman B, Siangphoe U, Warren JL, Klabunde CN. Association of polypectomy techniques, endoscopist volume, and facility type with colonoscopy complications. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77(3):436–446. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orsoni P, Berdah S, Verrier C, Caamano A, Sastre B, Boutboul R, Grimaud JC. et al. Colonic perforation due to colonoscopy: a retrospective study of 48 cases. Endoscopy. 1997;29(3):160–164. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1004156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang S, Li M, Fu T, Shan F, Jiang L, Shao Z. Clinical characteristics of infections caused by Streptococcus Anginosus Group. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):9032. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-65977-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Admon D, Gottehrer N, Leitersdorf E. Is "primary" subphrenic abscess caused by Streptococcus milleri a result of unrecognized gastrointestinal perforation? Klin Wochenschr. 1986;64(6):287–289. doi: 10.1007/BF01711940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faigel DO, Eisen GM, Baron TH, Dominitz JA, Goldstein JL, Hirota WK, Jacobson BC. et al. Tissue sampling and analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57(7):811–816. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(03)70047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitlock EP, Lin JS, Liles E, Beil TL, Fu R. Screening for colorectal cancer: a targeted, updated systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):638–658. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehta NY, Copelin IE. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): 2021. Abdominal Abscess. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sirinek KR. Diagnosis and treatment of intra-abdominal abscesses. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2000;1(1):31–38. doi: 10.1089/109629600321272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schein M. Surgical management of intra-abdominal infection: is there any evidence? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2002;387(1):1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00423-002-0276-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.