Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has put pressure on the informal sector, especially in developing countries. Regarding the case study found in Yogyakarta Special Region (Indonesia), this research focuses on workers in the informal sector with the following objectives: (1) to assess the impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on informal workers’ conditions, (2) to identify their strategies for surviving the crisis, and (3) to analyze the existing social safety net to support their livelihood. This study surveyed 218 respondents who worked in the informal, non-agricultural sector. The data were analyzed using descriptive statistical techniques. The results confirmed that most respondents underwent a decrease in working hours and incomes. In general, they have particular coping mechanisms to survive. The results also found that most respondents had high hopes for social assistance to stabilize their livelihood. Several government programs had been issued, either by improving policies before the pandemic or by creating new ones. However, there were many barriers and challenges to implementing them so that some recommendations had been suggested in this study to help the informal workers to become more resilient.

Keywords: COVID-19, Economic crisis, Informal economy, Indonesia

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has hard hit not only people's health but also the economy. Since its emergence in Wuhan at the end of 2019 and then declared as a global pandemic on March 11, 2020, COVID-19 has caused big chaos in the global economy, especially in transportation, tourism, and global supply chain (Ozili and Arun 2020). The World Bank (2020a) predicts that global gross domestic product (GDP) will contract by 5.2% in 2020, the biggest recession in decades. The economic growth will contract in all regions, such as East Asia and Pacific (0.5%), South Asia (2.7%), Sub-Saharan Africa (2.8%), Middle East and North Africa (4.2%), Europe and Central Asia (4.7%), and Latin America (7.2%) (World Bank 2020b).

The impact of COVID-19 on the economic sector is badly felt, especially for those in the informal sector. The International Labour Organization (ILO) has predicted that 1.6 billion workers in informal sectors would be significantly affected by COVID-19, a decline in income is predicted to reach 60% globally (ILO 2020a). Furthermore, other consequences resulting from COVID-19 are an increase in unemployment and underemployment rate, as well as large-scale economic restructuring (ILO 2020b). There will be 436 million informal businesses estimated to be at high risk of being hit by the economy during the pandemic, such as 111 million in the manufacturing, 51 million in the accommodation and food, and 42 million in other businesses (ILO 2020a). The informal workers have a relatively high vulnerability because they do not have social safety nets like those who work in the formal sector (Tim Forbil Institute and IGPA 2020).

Indonesia is one of the countries worst hit by this pandemic. Since the first case in March 2020, the number of positive cases did not show decline until September 2020. The total positive case as of September 3, 2020, was 184,268 cases across 34 provinces in Indonesia (Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia 2020). The absence of signs of the decline has put Indonesia in an uncertainty, which has a negative impact on the Indonesian economy. The Statistics Indonesia (BPS) data shows the economic growth in Indonesia in the second quarter to be in deep contraction, with the GDP growth according to the expenditure method down by − 5.32%. The contraction in economic growth was largely influenced by the decline in private consumption. The impact of the crisis will be felt, especially in the informal sector as it dominates employment conditions in Indonesia (with 57.27% of workers in the informal sector in 2019 based on BPS data).

In the two previous crises in Indonesia, i.e., the Asian Financial Crisis 1997–1998 and the Global Financial Crisis 2008–2009, the informal sector was able to survive because it had high flexibility in business and employment (Pitoyo 1999, 2007; Tambunan 2010). The flexibility of this sector to absorb workers without specific criteria has made this sector important in a crisis. In general, a crisis will result in a layoff wave which then triggers unemployment. The informal sector, in this condition, acts as a buffer zone to absorb excessive labour. This has happened in many countries where there was an increase in the number of the informal sectors during the crisis due to downsizing of the public sector and the entry of the population to the informal sector to survive (Pitoyo 1999, 2007; Dimova et al. 2005; Looney 2006; Tambunan 2010; Rothenberg et al. 2016; Jaskova 2017; Colombo et al. 2019).

Some scholars argue that the informal sector would not survive during this crisis. The absence of social protection and other benefits like what has been received by the formal workers causes workers in the informal sector to be included in the vulnerable group (Benjamin et al. 2014). Rothenberg et al. (2016) also explained that the informal sector, particularly in Indonesia, seems not eager to register its business to avoid taxes and does not have the intention to expand its business on a larger scale. Unclear legal status makes the informal sector often miss data collection on social protection assistance (Angelini and Hirose, 2014; Mehrotra, 2009; Huong et al., 2013). In terms of COVID-19 pandemic, Pitoyo et al. (2020) predicted that informal sector would not survive due to the slowdown of socioeconomic activities. Thus, a new study is needed to explain how the COVID-19 pandemic affects the informal sector.

Another problem that is interesting to study is how the informal workers respond to the impact of pandemic. This issue is rarely studied since many scholars just focus on how to make policies to help workers survive. One of the instinctive ways for workers to meet their needs and survive in times of crisis is through adaptive strategies. For example, Mahani (1999) found that informal food traders’ strategies in dealing with crises include increasing selling prices, reducing production, eliminating or replacing certain products, reducing product size, laying off workers, and improving service to customers. Dahles and Prabawa (2013) investigated the income-generating strategies of pedicab drivers during the crisis ranging from changing market orientation, selling assets, seeking alternative income sources, and relying on help from relatives. COVID-19-induced economic crisis is a new experience, so it may show a different kind of livelihood strategies. An updated and comprehensive study is needed to discover it.

This research topic has great urgency since it can elaborate on the socioeconomic perspective on the adaptation of workers in the informal sector during the crisis and analyze the gap in social protection policy interventions that are still needed. Understanding how an individual maintains their livelihood can help in formulating policies and intervening in their current adaptive strategies (Allison and Horemans 2006). Besides, it can evaluate the weaknesses of the existing intervention policies which only pay attention to quantitative parameters (such as their income rate) and tend to ignore workers’ social factors in dealing with problems caused by the crisis. Based on the cases noted above, this study has the main objectives of being able to capture the impacts of COVID-19 on working conditions in informal sector empirically and, at the same time, finding out the responses made by individuals through their livelihood strategy as well as external responses carried out by the government or parties other than workers in the informal sector.

Methods

Description of Study Area

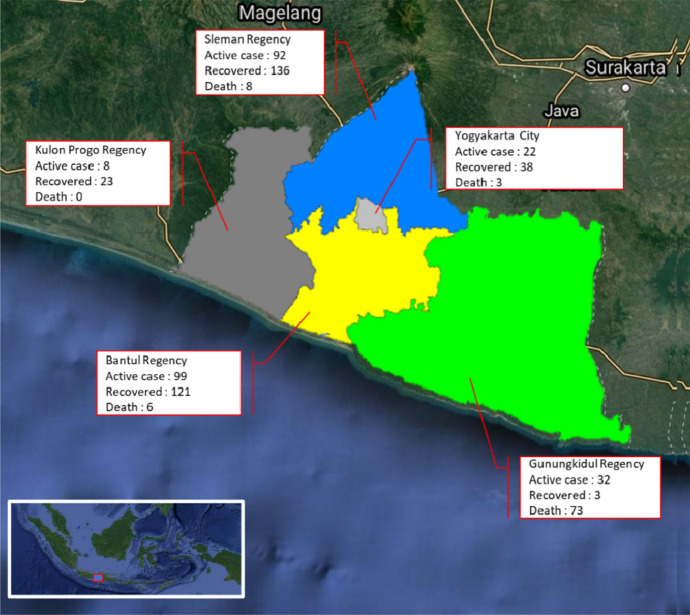

This study took a case study in the Special Region of Yogyakarta (known as Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta or DIY in short), one of the provinces located in Java (Fig. 1), that is an island with the most densely populated area and a high level of urbanization in Indonesia (Firman 2017). It is directly adjacent to the Central Java Province on the north, west, and east side, while on the south side, it is directly adjacent to the Indian Ocean. Based on data obtained from BPS in 2019, the population in DIY reaches 3,842,932 people and spread over five regencies/cities with a total population of 1,219,640 people in Sleman, 430,220 people in Kulon Progo, 1,018,402 people in Bantul, 742,731 people in Gunungkidul, and 431,939 people in Yogyakarta City.

Fig. 1.

Location of study area and distribution of COVID-19 cases as of July 31, 2020.

Source Google Earth and Health Department of DIY

During the COVID-19 pandemic, DIY became one of the provinces in Indonesia with a high number of confirmed positive cases, reaching 674 as of July 31, 2020 (Fig. 1). The cases have spread across five regencies/cities, such as 236 cases in Sleman, 226 cases in Bantul, 108 cases in Gunungkidul, 31 cases in Kulon Progo, and 63 cases in Yogyakarta City. While the number of cases increased, other impacts began to appear in DIY, one of which was economy.

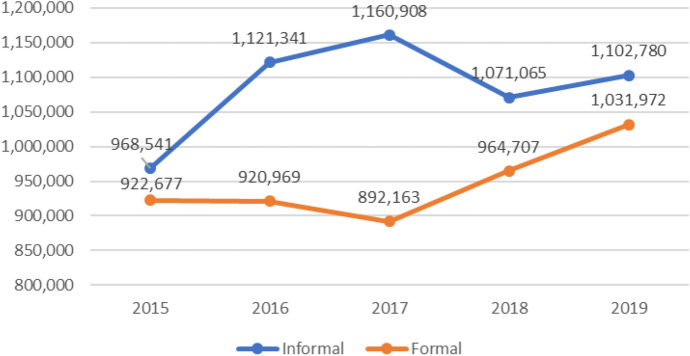

DIY is a province with the lowest economic growth in Java, i.e., − 6.74% (year over year), as the result of the COVID-19 pandemic. This low growth rate as compared to national level is caused by the decline in the performance of the tourism industry and its supporting sectors, including the informal sector. This weakening growth has also contributed to increasing the number of poor people. Based on BPS estimation, this pandemic will increase the poor to 475,720 and the open unemployment rate to 3.3%. DIY has an employment structure that is dominated by the informal sector (Fig. 2). The informal and formal sectors in DIY fluctuated from 2015 to 2019. Nevertheless, the informal sector in DIY tends to increase due to the increasing difficulty in reaching the formal sector as well as the social and economic conditions that support the high tourism and education sectors. The numbers in the informal sectors were 1,102,780 in 2019 or 52% of the workers according to their main occupation status, while the numbers in the formal sectors was 1,031,972 or 48% of the workers.

Fig. 2.

Number of workers aged 15 years and over by main occupation status in DIY.

Source Statistical Yearbook of DIY 2015–2019

DIY was selected to be the study area since this province is unique in representing the conditions of the informal sector during the pandemic. The informal sector in DIY is closely related to public activities, such as tourism and education, as well as to formal activities. Therefore, the description of the impact of COVID-19 on the informal sector is more observable in this province.

Data Collection and Analysis Technique

This study used primary data obtained from a combination of non-probability sampling (i.e., accidental, voluntary, and purposive sampling) approaches to get as many participatory responses as possible. The respondents were workers in the informal sector in DIY. Each respondent only represents one household. The surveys were held on July 1–31, 2020, which is in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. The new normal policy was initially issued in July. Since the situation had not improved, the government finally extended the emergency response period.

Collecting social survey data during a pandemic is a challenging process because it is difficult to directly interact with participants for the sake of safety. Therefore, this study has attempted to distribute online questionnaires through personal messages and social media groups. The potential for bias is relatively high, and the survey results cannot represent the conditions of all informal groups (Nayak and Narayan 2019). However, this method is still capable of providing actual and up-to-date data for policy considerations. Direct surveys were also conducted on July 28–29, 2020, in several informal activity centers in DIY to maximize the number of respondents as well as to observe the situation by implementing health protocols.

The design of questions consists of five main parts: the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents, the conditions of work and income before and during the pandemic, livelihood strategies, and social safety nets. The questionnaire is a combination of open-ended and close-ended types. The validation of the answers, particularly in online surveys, was then enabled. Several questions for certain themes were repeated to improve the answers’ accuracy and consistency. Before being processing, the data cleaning was undertaken to remove the problematic data or improve the answers (without changing the context). The results were analyzed using descriptive techniques.

Results

Characteristics of Respondents

This study obtained 218 valid respondents in DIY. The socio-demographic characteristics of respondents are briefly presented in Table 1. Nearly three-quarters of the respondents were men. Most of the respondents fell in the age group of 20–39 years (49.1%), followed by the age group of 40–59 years (39.4%). There were two young respondents (< 20 years), while the rest belonged to the elderly group aged ≥ 60 years.

Table 1.

Summary of the respondents’ social demographic characteristics

| Characteristics | Number | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 163 | 74.8 |

| Female | 55 | 25.2 |

| Age | ||

| < 20 | 2 | 0.9 |

| 20–39 | 107 | 49.1 |

| 40–59 | 86 | 39.4 |

| ≥ 60 | 23 | 10.6 |

| Demographic status | ||

| Migrant | 72 | 33.0 |

| Non-migrant | 146 | 67.0 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 38 | 17.4 |

| Married | 170 | 78.0 |

| Widowed/divorced | 10 | 4.6 |

| Highest completed education level | ||

| No schooling completed | 8 | 3.7 |

| Elementary school/equivalent | 25 | 11.5 |

| Junior high school/equivalent | 29 | 13.3 |

| Senior high school/equivalent | 115 | 52.8 |

| No schooling completed | 8 | 18.8 |

Most of the respondents were non-migrant (whose current living places are the same as that of birthplace at the regency or city level), that was around 146 out of 218 people. The proportion of informal migrant workers was also quite high, reaching 33%. Most of the respondents were currently married. Only 17.4% of the respondents were unmarried, and the rest were widowed or divorced. Married households are usually more active than those with other marital statuses because they have a larger household size as an asset for productive labour (Kom et al. 2020).

This study found that most respondents had a relatively high level of education. More than half of the respondents have graduated from senior high school education or equivalent, even the proportion of respondents who have graduated from university is the second highest. This finding is consistent with the statement that the informal sector is in demand not only by groups with low education status but also by those with better education status (Armansyah et al. 2019). Besides, BPS data showed that the open unemployment rate in this area was dominated by people with high school education or equivalent with a proportion of 28.1% in 2019. The informal sector is estimated to be able to absorb the educated workforce who do not have the opportunity to work in the formal sector. In other words, working in the informal sector is better than being unemployed.

The job and income characteristics of respondents are briefly presented in Table 2. These characteristics refer to the situation before the COVID-19 pandemic. This study had respondents with diverse types of main occupations. In general, all of them were classified as non-agricultural workers in the informal sector. Furthermore, this study classifies workers in the informal sector into three types (Octavia 2020) due to the high variation in the number of respondents according to the main type of work, i.e., own account with enterprise (43.6%), own account with task-based incomes (38.5%), and salaried workers without a formal contract (17.9%).

Table 2.

Summary of characteristics of respondents’ occupation and income

| Characteristics | Number | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Main occupation types | ||

| Own account, enterprise | 95 | 43.6 |

| Own account, task-based income | 84 | 38.5 |

| Salaried, without formal contract | 39 | 17.9 |

| Working experience (years) | ||

| < 1 | 4 | 1.8 |

| 1–5 | 100 | 45.9 |

| 6–10 | 39 | 17.9 |

| 11–20 | 38 | 17.4 |

| > 20 | 36 | 16.5 |

| Monthly incomes during normal situation (IDR) | ||

| > 1,500,000 | 61 | 28.0 |

| 1,500,000–3,000,000 | 98 | 45.0 |

| 3,100,000–6,000,000 | 47 | 21.6 |

| > 6,000,000 | 12 | 5.5 |

Most of the respondents have worked for 1–5 years (45.9%). The length of work shows the time deployed in the ongoing main occupation. Workers in the informal sector sometimes change the main type of occupation to adjust to the market dynamics (Handoyo and Setiawan 2018). However, the proportion of respondents who worked for more than 10 years was also relatively high. This condition proves that the informal sector is not only the first stepping stone before working in the formal sector, but is also a target as the main source of livelihood. Work experience can also influence the ability to cope with and adapt to crises.

The survey results confirm that informal workers earned diverse monthly incomes during the pre-pandemic situation. Most of them earned money ranged from IDR 1,500,000 to IDR 3,000,000 per month. The workers in the informal sector with the lowest income (less than IDR 1,500,000) were also found in this study. This income is even lower than the regional minimum wage standard for the formal sector determined by the regional government (IDR 1,704,608.25). However, it should be noted that not all workers who work in the informal sector are classified as poor, as some respondents had very high incomes during normal situations.

The Impact of COVID-19 on Working Conditions

Since the positive cases have been discovered in Indonesia on March 2, 2020, the issue of COVID-19 has developed in Indonesia and the government has responded to the declaration of COVID-19 as a national disaster through Presidential Decree No. 12/2020. Meanwhile, the number of positive cases has continued to increase, and the impacts on other sectors (including economy) have followed it as well. Based on the survey results, most of the respondents (38%) started to get the impact of COVID-19 on their work in mid-March, 26% of them at the end of March, 17% of them in early April, and 19% of them from mid-April to June. Based on the workers’ perspective, there were at least two major impacts of COVID-19 on working conditions, i.e., changes in working hours and income.

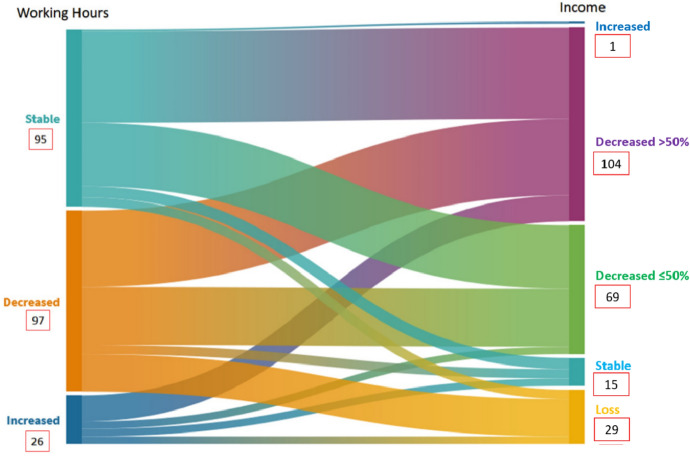

Most of the respondents (44.5%) faced a fall in the working hours (Fig. 3). It is in line with the ILO (2020a) prediction that the second quarter of the pandemic can lead to a working hours decrease. However, the survey results also showed that 11.9% of the respondents gained an increase in the working hours and 43.6% of respondents did not experience any changes in working hours. It indicated that some informal workers could maintain or determine their working hours during the crisis. Such condition was mostly found in self-employment types.

Fig. 3.

Alluvial plot of changes in working hours and income

Another impact of COVID-19 on workers in the informal sector was income. Based on the survey results, most workers (47.7%) felt that the COVID-19 pandemic caused an income decline of more than 50%, 13.3% of the respondents lost their income, 31.7% of them got a decrease of ≤ 50% of their income, and 6.9% of them did not experience the changes in income. A unique fact from this survey showed that there is one person who has the opposite condition, which is experiencing an increase in income, i.e., online seller. This job is indeed more desirable during the pandemic due to limited community movements and more effective to avoid exposure to the coronavirus.

Working hours and income are two interrelated variables. The working hours will be directly proportional to work productivity. Most of the workers who got the working hours decrease also experienced income decrease. However, those who got an increase in working hours did not have their income to increase. It is indicated that the main problem lies in the demand that comes from community activities during the crisis. The income reduction was influenced by a demand decrease for services or goods. Besides, the income decrease in paid workers was caused by the wage decrease from the company as a result of the business performance decreased during the pandemic. Therefore, balancing supply–demand is the key to restoring the income of workers in the informal sector in the context of this pandemic crisis.

Livelihood Strategies

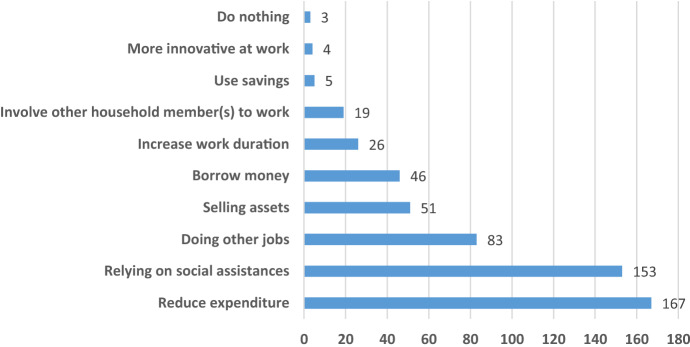

Based on the survey, it is found that 28% of respondents still felt the same conditions in July as at the beginning of the pandemic, while most of them (42.2%) stated that their condition was worse than that at the beginning of the pandemic. Meanwhile, 28.4% of the respondents stated that they see the signs of a slight improvement in their income due to the community’s activities increase that have adapted to the conditions during the pandemic. This study has tried to analyze their strategies to meet household needs due to difficult situations (Fig. 4). They are estimated to have mechanisms of their own to keep them to survive, although it may not necessarily improve their economic conditions to recover as earlier. In this regard, respondents were pleased to answer more than one answer.

Fig. 4.

Strategies done by informal workers to survive during the COVID-19 pandemic

The results suggest that most of the respondents stated that they reduced their spending (76.6%). It is very logical if it becomes the dominant choice since it is the first way to achieve the household economic balance when the income decreased during a crisis (Xu et al. 2015). Also, Wildayana et al. (2018) states that reducing spending is one of the best choices made by households during a crisis, which includes the management of food supplies and allocating spending for prioritized needs. The strategy of relying on social assistance was the action most carried out by the workers during the crisis after reducing spending by a proportion by 70.2%. This assistance was provided by the government or non-governmental actors in the form of cash or non-cash. The workers in the informal sector were expecting social assistance due to their income decrease or loss, to cope with the pressures of meeting life needs during the pandemic.

Most of the respondents also stated that they did another job to increase their income. The side job became an alternative because they cannot depend on the main occupation. Some of them have done the same while in the normal situations, as well as those who have changed their main occupation during the COVID-19 pandemic, who might still be in the same sector. Besides, many of the respondents had to sell their land and jewelry or pawn other assets because their income was sometimes unable to cover their needs. Many of the people also borrowed money to add their savings, which is usually done by those who do not have sufficient savings or assets to sell. It is in line with Xu et al. (2015) which stated that asking for a loan is a household’s last step to strengthen financial capital during a crisis, by utilizing both the existing social relations (friends and relatives) and financial institutions (formal and informal institutions).

The COVID-19 crisis has resulted in working hours decrease, even causing them to fall into unemployment. Such situation was also found in some members of the household. Uniquely, there were 26 respondents who said that they were desperate to increase their work duration to increase their income. Nineteen respondents stated that there was an increase in the number of household members who worked during the pandemic. The household members basically belong to economic assets so that they are fully maximized to survive in difficult conditions. Child labor might be involved to maximize income or housewives who end up working to help their husbands, which causes a double burden for them. Unpaid family workers were also often found in the informal economy, especially in family-owned businesses (Cuevas et al. 2009). A few respondents answered other strategies, such as using savings and innovating at work (e.g., changing marketing methods and targets), while three respondents stated that they did not implement specific mechanisms to survive during the pandemic.

Furthermore, this study tries to analyze the types of livelihood strategies during the pandemic carried out by workers in the informal sector. First, the productive strategy is the way to survive by maximizing the potential of productive assets to increase income, including doing other jobs, increasing working time, asking other household members to work, and making innovations at work. Second, sacrifice strategy refers to more passive efforts to survive during a crisis, such as reducing spending, selling assets, and using savings. These two strategies are internal in nature. Third, external support strategy is carried out by making use of the third parties and is not related to the use of existing assets in the household, such as asking for loans and social assistance.

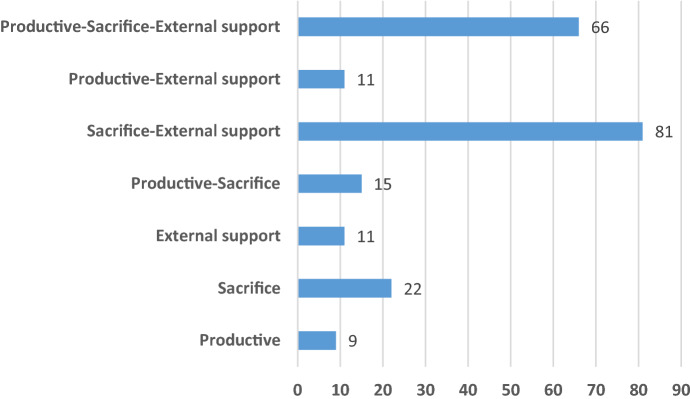

The results showed that most of the respondents adopted a multi-strategy to survive during the pandemic (Fig. 5). The combination of sacrifice and external support was mostly performed by 81 respondents, followed by combinations of all types of strategies by 66 respondents. The respondents mostly used them because they offered a higher chance of stabilizing their household economic situation rather than depending on a single strategy. Of the three types of strategies, most of the respondents performed the sacrifice strategy because it was relatively easy to do as a short-term response. More than half of the respondents also at least implemented the external support strategy, proving the importance of the role of external parties in supporting the livelihoods of workers in the informal sector during a pandemic.

Fig. 5.

Classification of informal workers’ livelihood strategies

In summary, this study finds that workers in the informal sector had alternative strategies to survive and overcome the difficulties in their livelihoods during a crisis. These strategies varied, depending on the economic condition and the livelihood capital owned by their household. The steps taken by the respondents though have not necessarily had promising prospects for recovering their livelihood. However, it was better than doing nothing. Several supporting steps still need to be taken so that workers in the informal sector can survive during the crisis.

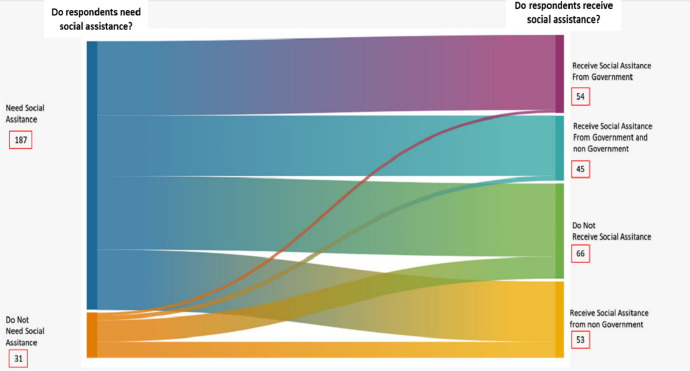

External Response Promotion

The economic crisis as a consequence of the pandemic has made some workers in the informal sector unable to survive solely on their internal response. Based on Fig. 6, 85.8% of the respondents needed social assistance to meet their daily needs during the pandemic. It shows that the economic burden is quite hard; hence, social assistance is another option for survival. However, some respondents felt that they did not need social assistance (14.2%). The external response aimed at supporting the workers in the informal sector’s survival consists of at least two main groups, i.e., social assistance provided by the government and non-governmental actors. Unfortunately, 26.7% of the respondents who need social assistance admitted that they had never received it from anyone. It is consistent with the preliminary study conducted by the Tim Forbil Institute and IGPA (2020) in the same area, showing that there are workers in the informal sector who have not been covered by the assistance scheme.

Fig. 6.

Alluvial plot of need for and access to social assistance

The government had several programmes aimed at addressing economic problems during the COVID-19 pandemic. The social safety net programmes of the central and regional governments consisted of the programmes that have generally been planned and implemented before the pandemic (with some improvisation) or just initiated during the pandemic. However, they had not been distributed evenly to people in need, including the affected workers in the informal sector. Based on the results of this survey, 55.1% of the respondents who need social assistance admitted that they had not received assistance from the government.

Social assistance mostly targets poor people. The Family Hope Programme (known as Program Keluarga Harapan or PKH in short), Staple Food Card (known as Kartu Sembako or KS in short), and Pre-employment Card (known as Kartu Prakerja or KP in short) are government programmes initially aimed at improving welfare, as well as alleviating poverty and unemployment (Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia 2020a; Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia 2020). The above assistances are not directly targeted to the workers in the informal sector. PKH is the social assistance in the form of health, education, and social welfare funding for the poor given every month (i.e., IDR 75,000—IDR 250,000) during the COVID-19 pandemic. KS is the social assistance in the form of funding of IDR 200,000 per month given to each poor since March 2020 and aimed at fulfilling their basic needs. Meanwhile, KP was once distributed in April 2020, where this program aims to develop work competence and entrepreneurship along with incentives with a total benefit of IDR 3,550,000 prioritized for the affected workers.

Several new programmes had been created by the government during the pandemic to support the existing social safety net schemes, such as electricity subsidies, incentives, and deferred credit payments for micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises, and cash transfers for the poor. The latter focuses on families who are entitled to receive social assistance but have not yet been covered by other cash transfer social assistance schemes. The Village Fund (Dana Desa) policy was basically intended to accelerate village development. However, 35% of the budget had been used during the COVID-19 pandemic as a social safety net in the form of cash transfers (Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia 2020b). Direct cash assistance from the Village Fund had been provided in May, June, and July (i.e., IDR 600,000 per household). The social assistance scheme with the same amount and distribution mechanism was also present with a combination of funding sources from the central government and the regional budget (Government of DIY 2020).

There is another new form of social safety net programme that focuses on the category of labourers, i.e., a wage subsidy of IDR 1,200,000 that is disbursed twice for four months (Ministry of Manpower of the Republic of Indonesia 2020). It benefits the vulnerable workers to increase their purchasing power during the pandemic. This assistance is intended for workers with wages of less than IDR 5,000,000 and registered as active participants in the government employment insurance. Unfortunately, this scheme cannot be accessed by workers in the informal sector due to administrative requirements. Another issue also relates to the absence of data on the distribution of workers in the informal sector.

The government has limitations in providing social assistance for informal workers because of lack of either data or funds. However, this has been helped by grassroots movements providing aid packages. Parents, relatives, and friends also have a crucial role in helping to survive during the crisis. Based on this study, 44.5% of the respondents got the assistance provided by non-government agencies. This assistance is in the form of money and basic foods (known as sembako) with diverse distribution times. The assistance had been given from March, and more respondents had received it from April to May. The increase coincided with the month of Ramadan and Eid al-Fitr, which is one of the important moments for Islam (the majority religion in DIY). It encouraged a great spirit of sharing so that it was thought to be one of the causes of the increasing intensity of the assistance, particularly through the voluntary charity (sadaqah) and the obligatory charity (zakat). The assistance provided by non-governmental organizations was generally temporary in nature and not continuous. However, in a certain period, the respondents could receive assistance more than once. The contributions given by family and friends, communities, and religious institutions in helping the vulnerable workers showed a strong social capital inherent therein (Mahendra 2015).

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic is regarded as a health problem. However, the changes in community activity patterns and government policies in controlling this disease then have significant impacts on informal workers. The previous study from India showed the same case where 90% of the street vendors could not work during the pandemic (ILO 2020c). Also, 44% of the workers in the informal sector in Peru had an income decrease (ILO 2020d). The working hours decrease was caused by restrictions on community activities, such as policies to restrict business operations.

Previous studies from Pakistan (Shafi et al. 2020), India (ILO 2020c), and South Africa (ILO 2020e) also showed the same indications in which lockdowns made most workers in the informal sector lose their jobs. The paid workers without a formal contract had the working hours and income decrease as well. A recent study from Bartik et al. (2020) shows that the indications of worker’s dismissal are common because many businesses are trying to reduce their expenses.

Poor working conditions during a pandemic do not merely mean that workers in the informal sector plan to stop their businesses or change their job. Most of them think that changing a job or business during a pandemic is difficult because they think that no one has survived the pandemic crisis. This fact is in line with the findings of Shafi et al. (2020) in their study conducted in Pakistan that only 4% of micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises planned to change their job during the pandemic. In addition to the perception of the difficulty of working opportunities, the limitation on the abilities and knowledge also causes the informal workers do not change their job. Those who have planned to change their job are relatively well educated (e.g., high school or university graduates). Salaried workers without formal contracts generally want to change their job by running a small business if their working conditions do not improve during or after the pandemic. The types of informal businesses do indeed become “the escape” for workers who have lost their income due to a lack of demand for their services or for those who have been dismissed. It may happen because informal businesses do not require much capital but are still able to provide profits that can support workers’ living needs. The existence of informalization has the potential to increase the competition which can then reduce the workers’ income in their account enterprise sector.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on working conditions can extend beyond working hours and income. The poor working conditions trigger the informal migrant workers in urban areas to do return migration, like what happened in India that underwent a high wave of urban–rural migration when the lockdown was applied and many workers lost their jobs (Biswas 2020). Migrant workers in the informal sector are the most vulnerable ones because they are often out of domicile-based social assistance. Furthermore, a condition without income also makes migrants lose their homes because they cannot pay the rent cost (Biswas 2020; Ghani 2020; ILO 2020c). A study from Pakistan shows that the pandemic crisis causes five million Pakistanis who depend on their daily income to be in poverty (Hussain 2020). The same situation is predicted to occur in Indonesia, where BPS reports an additional 1.63 million poor people by September 2020 (an increase of 0.53% compared to the last year). Meanwhile, the number of poor people has increased in DIY by 34,800 people as of September 2020.

The conditions of the informal sector during the pandemic are highly different from those during the previous financial–economic crises in Indonesia. The disruption of supply chains, changes in community activities, and health vulnerabilities are new experiences for workers in the informal sector. This condition is exacerbating because they cannot restore their productivity, while they also do not get social assistance specifically to support their job security. Therefore, the informal economy is the worst affected sector in this pandemic condition. It then has an impact at the national level, considering that this sector is the economic foundation of developing countries. Based on data from BPS in 2019, 70.49 million people who work in the informal sector will face high livelihood risks during the pandemic.

Although workers in the informal sector do not get as much attention as formal workers, a number of studies have proven that they try to do the strategies to get out of their limitations (Nangia 1994; Agyei et al. 2016; Handoyo and Setiawan 2018; Hidalgo 2019; Danso and Weredu 2020). However, the crisis can exacerbate their vulnerability, leading to falling into or even worsening poverty. In this regard, Suharto (2002) mentioned that there are at least three reasons underlying this condition based on the previous crises, such as (1) an increase in strict competition in line with the increasing rate of informality, (2) an increase in the price of production inputs and raw materials, and (3) a combination of net profit has reduced, the aftereffects of currency depreciation, and inflation.

Previous research has investigated informal workers’ adaptive strategies to survive the crisis (Mahani 1999; Dahles and Prabawa 2013). This study also found similar results, where almost all respondents made various efforts to overcome the effects of the pandemic-induced crisis. Most of the respondents combined various strategies, but they did not do the productive strategy more than the other types of strategy due to several limitations, e.g., some workers in the informal sector do not have the opportunity to find another job due to tighter competition and limited skills as well as the unfavorable market situations. As a result, those who lose their job are still trapped in unemployment. They also found it difficult to work harder (e.g., increasing the work duration) due to the obstacles from government policies, such as social restrictions. This condition is a challenge for them because it is not common in previous financial crises. It is almost impossible for them to be encouraged to work from home because they mostly rely on earning money from outside the home.

The informal workers’ responses in facing the pandemic must be integrated with social assistance support schemes. The central government in collaboration with the local governments has issued several social safety net programs (including for indirectly affected workers), but some obstacles are still found. First, not all social assistance schemes are accessible to informal workers, e.g., the wage subsidy program can only target paid workers who are registered in government employment insurance. Also, insurance participants are dominated by formal workers or those with official employment relationships even though social security is basically for all workers. This is due to certain administrative requirements that most workers in the informal sector find it difficult to fulfill. Other main reasons are the lack of knowledge and inability to pay the insurance premiums (ILO 2010). Second, the government does not have definite data regarding the distribution of informal workers. Most of the informal enterprises are not registered, where this condition can be affected by the willingness to pay tax (Rothenberg et al. 2016; Osemeke et al. 2020). Besides, middle-class workers in the informal sector are threatened with economic paralysis because they have not been classified as subsidized recipients before the crisis, placing them as the most vulnerable group than the poor. Third, the assistance packages in the form of cash transfer or in-kind distribution do not necessarily guarantee the fulfillment of low-income groups during the pandemic. Additional actions that trigger a more productive strategy are needed as an initial stage for livelihood redevelopment, particularly to increase innovation.

The crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic offers new hope for paying attention to the informal sector better than ever. Therefore, Octavia (2020) suggests that labor regulations in Indonesia need to have a review so that workers in the informal sector are recognized and get special protection. The development of a database of people working in the informal sector is needed through a specific platform. This scenario needs support from high awareness of informal workers for self-registration or must be facilitated by certain parties, such as local administrative authorities, companies, communities with workers in the informal sector in the same field, or non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that advocate the issue of the shadow economy. Rapid tracking is needed to detect the most vulnerable workers in the short term during an emergency. One of the best examples found in DIY is the identification of affected micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises through an online database system called SiBakul Jogja.

The next problem is that the social assistance programs provided by the government are more based on the poverty status of a person or household even though not all workers in the informal sector are classified as poor (Octavia 2020). Besides, this pandemic has also caused a new wave of the poor who are often not helped with social assistance since the assistance is provided according to pre-pandemic classifications. However, it can be complemented by the existence of social movements from individuals and organizations. Social concern among communities is an important asset to fill this gap because social movements can reach a wider group. Workers in the informal sector who do not receive assistance usually rely on assistance from grassroots organizations or movements (Octavia 2020).

The social capital of the DIY community was quite high during the pandemic. In general, there are two existing non-governmental assistances, i.e., those from individuals and organizations, for the needs of education, social, and religion. This kind of social capital is supported by a moment in the early days of the pandemic, which coincides with the month of Ramadan and Eid al-Fitr in which the tendency of people in DIY to share is high at this moment. Accordingly, vulnerable workers in the informal sector who are not reached by government assistance schemes can survive because of this social assistance. The sporadic movements of the philanthropists are very beneficial, especially for migrants who are not registered as recipients of assistance in their workplace. A study from Iceland during the 2008 crisis found that the role of social relationships between family members and non-family members is very crucial in getting someone out of trouble due to the economic crisis (Growiec et al. 2012).

This pandemic causes difficulty in decision making since it has to be considered, for the sake of both health and economic aspects. Informal workers face two high risks, i.e., the potential to be infected by the virus while working or being hungry if they do not go to work. Purnomo (2020) states that informal businesses can still be run during a pandemic as long as it is integrated with standard and additional protocols for each business sector as a middle way to save people's lives and livelihoods. Difficult conditions also require entrepreneurs to be more creative, e.g., the presentation of food that must be more hygienic and durable or among entrepreneurs to expand business scope. Reorientation of good and service products can be an alternative for affected workers in the informal sector by looking at the developments in demand, e.g., health protection equipment or personalized assistance (Narula 2020). This action may require reskilling and upskilling to improve and increase the capability to take advantage of market demand (ILO 2020e). Therefore, government support in the form of cash for work can also be integrated into the scheme to create job opportunities for unemployed people.

Another step to adapt during a pandemic is to run an information technology-based economic business (Shafi et al. 2020). On the one hand, it becomes a response to changes in people’s safer shopping style. Digital transformation also offers consumer coverage and product branding on a higher scale. On the other hand, Purnomo (2020) states that there are challenges faced in this reform, such as (1) access to digital infrastructure is inadequate, so the level of digital ecosystem connectivity is low, (2) competition is getting higher, (3) stuttering in dealing with business characteristics which require fast and realistic responses, (4) limited digital literacy, and (5) limited knowledge on financial management during a crisis.

Conclusions

The informal sector is too is impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. This pandemic has a major impact on working hours, decrease in the majority of workers in the informal sector, as well as the income decrease. The impact of the pandemic started to hit them shortly after the COVID-19 issue developed in Indonesia and the government applied large-scale social restrictions. Their current conditions of living vary, ranging from getting worse to better. In the face of this pandemic, workers in the informal sector adopted a livelihood strategy dominated by the sacrifice type, especially by saving household spending. The bad impact of the pandemic on their livelihoods has caused most of them to expect social assistance, but many of them do not get it.

This study concludes that the informal sector is one sector that has been severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. It is unable to survive the crisis due to the pandemic, even though the informal sector was relatively resilient in the previous economic crisis. The role of the government’s social assistance is very crucial in supporting the livelihood strategies for workers in the informal sector. Therefore, social safety nets need to be improved in terms of the quantity and accuracy of the assistance target.

This crisis provides a window of opportunity to pay better attention to the informal sector, particularly in countries with a dominant share of informal employment. The recording of informal workers’ data is fundamental to protect them in an emergency situation. They also need to upgrade their business to be more resilient. Labor regulations should recognize the existence of the informal sector in a broader scope and consider it in a special protection scheme since this sector can basically develop like that of the formal sector.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Muhammad Ilham Fathurrizqi, Fikri Nurrachman Ernawan, Muhammad Galih Prakosa, Esya Rachma Ningrum, and Environmental Geography Student Association (EGSA) for their support during the research.

Funding

This research was fully funded by RTA (Rekognisi Tugas Akhir) Program 2020 from Universitas Gadjah Mada, grant number 2607/UN1/DITLIT/DIT-LIT/PT/2020.

Data availability

The data used are available with the authors and can be available upon demand.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors confirm this research is original and there is no conflict of interest for this research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Agyei YA, Kumi E, Yeboah T. Is better to be kayayei than to be unemployed: Reflecting on the role of head portering in Ghana’s informal economy. GeoJournal. 2016;81:293–318. doi: 10.1007/s10708-015-9620-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allison EH, Horemans B. Putting the principle of sustainable livelihoods approach into fisheries development policy and practice. Marine Policy. 2006;30:757–766. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2006.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Angelini, J., and K. Hirose. 2014. Extension of social security coverage for the informal economy in Indonesia. ILO Working Paper 11.

- Armansyah, Sukamdi, Pitoyo AJ. Informal sectorA survival or consolidation livelihood strategy: A case study of the informal sector entrepreneurs in Palembang City, Indonesia. Russian Journal of Agricultural and Socio-Economic Sciences. 2019;11:104–110. doi: 10.18551/rjoas.2019-11.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartik A, Bertrand M, Cullen ZB, Glaeser EL, Luca M, Stanton C. How are small businesses adjusting to COVID-19? Early evidence from a survey. Harvard Business School Working Paper. 2020;20:1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, N., Beegle, K., Recanatini, F., and Santini, M. 2014. Informal economy and the World Bank. Policy Research Working Paper 6888. 10.1596/1813-9450-6888.

- Biswas, S. 2020. Coronavirus: India’s pandemic lockdown turns into a human tragedy. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-52086274. Accessed 11 Oct 2020

- Colombo E, Menna L, Tirelli P. Informality and the labor market effects of financial crises. World Development. 2019;119:1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia. 2020. Pemerintah resmi buka pendaftaran Kartu Prakerja tahap pertama. https://www.ekon.go.id/publikasi/detail/226/pemerintah-resmi-buka-pendaftaran-kartu-prakerja-tahap-pertama. Accessed 2 Oct 2020.

- Cuevas, S., C. Mina, M. Barcenas, and A. Rosario. 2009. Informal employment in Indonesia. ADB Economics Working Paper Series 156.

- Dahles H, Prabawa TS. Entrepreneurship in the informal sector: The case of the pedicab drivers of Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship. 2013;26:241–259. doi: 10.1080/08276331.2013.803672. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Danso-Weredu EY. Saving from one another: The informal economy of subsistence among the urban poor in Ghana. GeoJournal. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10708-019-10123-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dimova, R., I.N. Gang and J. Landon-Lane. 2005. The informal sector during crisis and transition. Research Paper 2005/18. UNU-WIDER, Helsinki.

- Firman T. The urbanisation of Java, 2000–2010: Towards ‘the island of mega-urban regions. Asian Population Studies. 2017;13:50–66. doi: 10.1080/17441730.2016.1247587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghani, F. 2020. How coronavirus shutdown affected Qatar’s migrant workers. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2020/6/11/how-coronavirus-shutdown-affected-qatars-migrant-workers. Accessed 27 Sep 2020.

- Government of DIY. 2020. Bansos warga terdampak COVID-19, cair dua hari lagi. https://jogjaprov.go.id/berita/detail/8677-bansos-warga-terdampak-covid-19-cair-dua-hari-lagi. Accessed 2 Oct 2020.

- Growiec, K., S. Vilhelmsdóttir, and D. Cairns. 2012. Social capital and the financial crisis: The case of Iceland. CIES e-Working Paper.

- Handoyo E, Setiawan AB. Street vendors (PKL) as the survival strategy of poor community. JEJAK: Jurnal Ekonomi dan Kebijakan. 2018;11:173–188. doi: 10.15294/jejak.v11i1.12510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo HA. Livelihood analysis for informal business: A tool toward community development intervention. ICCD. 2019;2:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Huong, N.T.L., L.Q. Tuan, M. Meissner, B.S. Tuan, D.D. Quyen, and N.H. Yen. 2013. Social protection for the informal sector and the informally employed in Vietnam: Literature and data review. IEE Working Papers 199. Ruhr-Universität Bochum: Bochum.

- Hussain, K. 2020 The coronavirus economy. https://www.dawn.com/news/1544172. Accessed 11 Oct 2020.

- ILO . Social Security for Informal Economy Workers in Indonesia; Looking for Flexible and Highly Targeted Programmes. Jakarta: ILO; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. 2020a. ILO Monitor: COVID19 and the world of work. Third edition updated estimates and analysis. Geneva: ILO.

- ILO. 2020b. COVID19 crisis and the informal economy: Immediate responses and policy challenges (ILO brief). https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/employment-promotion/informal-economy/publications/WCMS_743623/lang--en/index.htm. Accessed 12 Oct 2020.

- ILO. 2020c. COVID-19 and the informal sector: What it means for women now and in the future (Policy brief). https://www.empowerwomen.org/en/resources/documents/2020/07/covid-19-and-the-informal-sector-what-it-means-for-women-now-and-in-the-future?lang=en. Accessed 12 Oct 2020.

- ILO. 2020d. Rapid response to COVID-19 under high informality? The case of Peru (ILO note). https://www.ilo.org/employment/units/emp-invest/informal-economy/WCMS_746116/lang--en/index.htm. Accessed 12 Oct 2020.

- ILO. 2020e. The impact of the COVID-19 on the informal economy in Africa and the related policy responses (ILO brief). https://www.ilo.org/africa/information-resources/publications/WCMS_741864/lang--en/index.htm. Accessed 12 Oct 2020.

- Jaskova A. Is informal employment a safety net in times of crisis? Evidence from Serbia. Journal of Human Resource Management. 2017;20:11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kom Z, Nethengwe NS, Mpandeli NS, Chikoore H. Determinants of small-scale farmers’ choice and adaptive strategies in response to climatic shocks in Vhembe District, South Africa. GeoJournal. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10708-020-10272-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Looney R. Economic consequences of conflict: The rise of Iraq’s informal economy. Journal of Economic Issues. 2006;40:991–1007. doi: 10.1080/00213624.2006.11506971. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahani. 1999. Analisis dampak krisis terhadap produktivitas dan efisiensi sektor informal pedagang kaki lima studi kasus: Warung makan kaki lima di Yogyakarta. Thesis, Yogyakarta: Universitas Gadjah Mada.

- Mahendra S. Keterkaitan modal sosial dengan strategi kelangsungan usaha pedagang sektor informal di Kawasan Waduk Mulur: Studi kasus pada pedagang sektor informal di Kawasan Waduk Mulur Kelurahan Mulur Kecamatan Bendosari Kabupaten Sukoharjo. Jurnal Analisa Sosiologi. 2015;4:10–30. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrotra S. The impact of the economic crisis on the informal sector and poverty in East Asia. Global Social Policy. 2009;9:101–118. doi: 10.1177/1468018109106887. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia. 2020a. PKH dan Kartu Sembako penuhi kebutuhan dasar masyarakat rentan miskin terdampak COVID-19. https://www.kemenkeu.go.id/publikasi/berita/pkh-dan-kartu-sembako-penuhi-kebutuhan-dasar-masyarakat-rentan-miskin-terdampak-covid-19/. Accessed 2 Oct 2020.

- Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia. 2020b. FAQ terkait kebijakan Dana Desa dalam rangka penanganan COVID-19. http://www.djpk.kemenkeu.go.id/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/FAQ-Dana-Desa-COVID-19.pdf. Accessed 2 Oct 2020.

- Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia. 2020. Situasi terkini perkembangan Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) 4 September 2020. https://covid19.kemkes.go.id/situasi-infeksi-emerging/info-corona-virus/situasi-terkini-perkembangan-coronavirus-disease-covid-19-4-september-2020/#.X3U3U-1x3IU. Accessed 4 Sep 2020.

- Ministry of Manpower of the Republic of Indonesia. 2020. Presiden Jokowi luncurkan bantuan subsidi gaji/upah bagi pekerja. https://kemnaker.go.id/news/detail/presiden-jokowi-luncurkan-bantuan-subsidi-gajiupah-bagi-pekerja. Accessed 2 Oct 2020.

- Nangia, P. 1994. Children in the urban informal sector: A tragedy of the developing countries in Asia. In: Dutt AK, et al. (Eds.) The Asian city: Processes of development, characteristics and planning. Springer, Dordrecht. 10.1007/978-94-011-1002-0_18.

- Narula R. Policy opportunities and challenges from the COVID-19 pandemic for economies with large informal sectors. Journal of International Business Studies. 2020;3:302–310. doi: 10.1057/s42214-020-00059-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak MSDP, Narayan KA. Strengths and weakness of online surveys. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science. 2019;24:31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Octavia, J. 2020. Towards a national database of workers in the informal sector: COVID-19 pandemic response and future recommendations. CSIS Commentaries, 1–8.

- Osemeke N, Nzekwu D, Okere RO. The challenges affecting tax collection in Nigerian informal economy: Case study of Anambra State. Journal of Accounting and Taxation. 2020;12:61–74. doi: 10.5897/JAT2020.0388. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ozili P, Arun T. Spillover of COVID-19: Impact on the global economy. MPRA Paper. 2020 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3562570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pitoyo AJ. Pedagang kaki lima pada masa krisis. Populasi. 1999;10:73–97. doi: 10.22146/jp.12485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pitoyo AJ. Dinamika sektor informal di Indonesia: Prospek, perkembangan, dan kedudukannya dalam sistem ekonomi makro. Populasi. 2007;18:129–146. doi: 10.22146/jp.12081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pitoyo, A.J., B. Aditya, and I. Amri. 2020. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic to informal economic sector in Indonesia: Theoretical and empirical comparison. In: E3S Web of Conference, 200, 03014. 10.1051/e3sconf/202020003014.

- Purnomo, B.R. 2020. Covid-19 dan resiliensi UMKM dalam adaptasi kenormalan baru. In: Mas’udi, W.M., and Winanti, P.S. (Eds.) New normal: Perubahan sosial ekonomi dan politik akibat COVID-19. Gadjah Mada University Press, Yogyakarta, pp 171–193.

- Rothenberg AD, Gaduh A, Burger NE, Chazali C, Tjandraningsih I, Radikun R, et al. Rethinking Indonesia’s informal sector. World Development. 2016;80:96–113. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shafi M, Liu J, Ren W. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises operating in Pakistan. Research in Globalization. 2020;2:100018. doi: 10.1016/j.resglo.2020.100018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suharto E. Profiles and dynamics of the urban informal sector in Indonesia: A study of pedagang kakilima in Bandung. Thesis: Massey University; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tambunan TTH. The Indonesian experience with two big economic crises. Modern Economy. 2010;1:156–167. doi: 10.4236/me.2010.13018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tim Forbil Institute and IGPA. 2020. Pekerja informal di tengah pandemi COVID-19. In: Mas’udi, W., and Winanti, P.S. (Eds.) Tata kelola penanganan COVID-19 di Indonesia: Kajian Awal. Gadjah Mada University Press, Yogyakarta, pp 238–252.

- Wildayana, E., M.E. Armanto, Z. Idrus, I.A. Radiatmoko, S.A. Umar, B. Syakina, et al. 2018. Surviving strategies of rural livelihoods in South Sumatra farming system, Indonesia. In: E3S Web of Conferences, 68, 02001. 10.1051/e3sconf/20186802001

- World Bank. 2020a. Global economic prospects. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- World Bank. 2020b. The global economic outlook during the COVID-19 pandemic: A changed world. www.worlbank.org/en/news/feature/2020/06/08/the-Global-Economic-Outlook-During-the-covid-19-pandemi-a-changed-world. Accessed 17 Aug 2020.

- Xu D, Zhang J, Rasul G, Liu S, Xie F, Cao M, et al. Household livelihood strategies and dependence on agriculture in the mountainous settlements in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area, China. Sustainability. 2015;7:4850–4869. doi: 10.3390/su7054850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used are available with the authors and can be available upon demand.