Abstract

Primary healthcare access is one of the crucial factors that ensures the health and well-being of a population. Immigrant/racialised communities encounter a myriad of barriers to accessing primary healthcare. As global migration continues to grow, the development and practice of effective strategies for research and policy regarding primary care access are warranted. Many studies have attempted to identify the barriers to primary care access and recommend solutions. However, top-down approaches where the researchers and policy-makers ‘prescribe’ solutions are more common than community-engaged approaches where community members and researchers work hand-in-hand in community-engaged research to identify the problems, codevelop solutions and recommend policy changes. In this article, we reflect on a comprehensive community-engaged research approach that we undertook to identify the barriers to equitable primary care access among a South Asian (Bangladeshi) immigrant community in Canada. This article summarised the experience of our programme of research and describes our understanding of community-engaged research among an immigrant/racialised community that meaningfully interacts with the community. In employing the principles of community-based participatory research, integrated knowledge translation and human centred design, we reflect on the comprehensive community-engaged research approach we undertook. We believe that our reflections can be useful to academics while conducting community-engaged research on relevant issues across other immigrant/racialised communities.

Keywords: health education and promotion

Summary box.

Researchers exploring community issues need to consider a community-engaged research approach whenever possible.

Meaningful community-engaged research is only possible when a sustained partnership with the community is achieved.

A substantial amount of groundwork is needed to develop a sustained partnership with the community that includes identifying key community members/influencers and building capacity within the community.

The research questions need to be identified based on community priorities, and the study should be designed such that community participants feel at home in guiding the research so they can contribute to the research more freely and effectively.

Researchers should ensure the results from the research are shared with the community.

Key community members who help connect researchers to the community in an ongoing way need to be supported; this could include compensation, career support and other incentives.

Introduction

Access to primary healthcare services is a determining factor for optimal health and well-being.1 Primary healthcare encompasses a range of services, including prevention and treatment of common diseases and injuries, referrals to and coordination with other levels of care (eg, hospital and specialist care), health promotion, maternal and child healthcare, and rehabilitation services.2 Immigrant/racialised communities continue to face a number of challenges when seeking primary healthcare in Canada.3–5 With over one-fifth of the Canadian population being foreign born,6 this lack of equitable primary healthcare access is an important issue for the healthcare system.7 8 While a number of studies have approached the issue from a problem identification perspective (describing the unmet needs or barriers faced by immigrants while accessing healthcare),4 5 there is a need for more solution-oriented research. Further, a meaningful community participation approach seems to be lacking while undertaking research on immigrants’ primary healthcare access.4 5 Community participation in the planning and conducting research on health problems and solutions9 is important to improve primary care access.

Community-based participatory research,10 integrated knowledge translation11 and human-centred design strategies12 are people-centred approaches of addressing pragmatic real-life issues where the community is engaged as partners. These collaborative approaches are built on equitably involving community members in all aspects of the process and enabling all partners to contribute their expertise and share responsibility and achievements.13 Community-engaged research guided by these approaches can play a crucial role in improving the health and wellness of immigrant/racialised populations through exploring the issues, identifying their root causes and developing potential solutions.

As part of our community-engaged programme of research on immigrant/racialised community health and wellness issues, we conducted several studies on primary care access barriers and possible solutions with an immigrant/racialised community in Canada. We aspired for meaningful and active involvement of the community in conducting research, priority setting, cocreating knowledge products and knowledge translation or mobilisation activities. The engagement was embedded within a participatory approach and thus entailed ongoing relationships between the researchers and community representatives. Engaging with a South-Asian community (Bangladeshi-Canadians), the experiences derived from our programme of research have informed our understanding of how to engage immigrant/racialised communities in community-based research. In this article, we reflect on a comprehensive community-engaged research approach we undertook to identify the barriers to equitable primary care access among the Bangladeshi immigrant community in an urban centre in Canada.

Building community partnerships through engagement

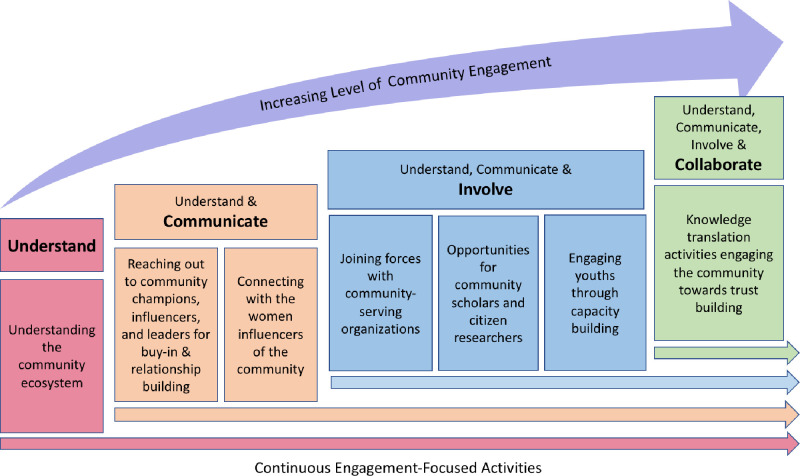

In building community partnerships, we employed approaches where meaningful community engagement strategies were at the core. Our approach was to be clear, consistent, and constant in communication and be flexible and open to complexity and ambiguity. Meaningful community engagement strategies need to be built on culturally responsive outreach. To ensure we accomplished our goal, the following steps reflect the meaningful community engagement approach we undertook as we prepared to commence research activities (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Continuous engagement-focused activities to achieve different levels of engagement. The levels of engagement were adapted from the participation spectrum described by the International association of participation professionals (IAP2).20

Understanding the community ecosystem

Understanding the community ecosystem was fundamental in guiding our community engagement process. We conducted a number of informal consultations with community members and conducted social media scans. Through this process, we were able to identify essential information, such as community champions, community influencers and community organisation leaders. We also developed understanding about the sociocultural organisation characteristics as well as community/social subgroups and their dynamics. Guided by the social justice principals of equity, diversity and inclusion, we wanted to understand about the different subgroups or pockets of the community so that we can make active efforts to reach to those pockets through our community-engaged programme of research. For our purpose, we considered community champions to be people from the community who are proactive in effecting social change and have natural leadership characteristics. Community influencers are those who are well known and respected in the community as a celebrity or appreciated figure, such as a singer, an artist, a language teacher, etc. A community leader is someone who has a designated leadership position in any type of community organisation. For example, in the Bangladeshi-Canadian community, we worked with in these studies, there are leadership positions (eg, president, general secretary, health and wellness secretary) within the Bangladesh Canada Association of Calgary (BCAOC). Identifying these people within the community and understanding community dynamics were extremely important in planning our outreach activities in the community.

Reaching out to community champions, influencers and leaders for buy-in and relationship building

We started our research by reaching out to community champions, influencers, and leaders to get their buy-in for our programme of research. We met with them in coffee shops, at community events and in community meeting spaces to explain our ideas and discuss how to move forward with them. With time, some of them became relatively more engaged than others. For example, the Health & Wellness Secretary of the BCAOC has been an active supporter and contributor of our research and knowledge translation efforts.

Connecting with the women influencers of the community

During the initial engagement, we realised that all of the community champions and influencers we were engaging with were men, as these groups are mainly led by men. As such, we developed a strategy to reach out to and engage with women influencers within the community in innovative ways through personalised invitations. We initially approached a few women we knew personally and discussed our work with them. We then requested that, as a snowballing approach, they connect us to those women to whom they felt we should reach out. In our experience, the women influencers were more enthusiastic to engage, and in the long run their involvement was more impactful and rewarding throughout the research process.

Joining forces with community-serving organisations

Within immigrant/racialised communities, a number of different organisations are usually active with a wide range of activities, including cultural, educational, religious, developmental, charitable and those involving social care and serving vulnerable members. These organisations also vary in their structures, with some being registered as a not-for-profit or charity, some as for-profit, and some with a very informal structure. For example, within the Bangladeshi-Canadian community in Calgary, there are sociocultural groups based on such aspects as professional identity (eg, agriculturalist association), educational institute attended (eg, University of Dhaka alumni), current profession (eg, geologist association), religious attachment (eg, Islamic study group, Hindu prayer group), and cultural group (eg, Bangla cultural group). The common thread among these organisations is the desire to contribute to overall community sociocultural development. We reached out to all of these organisations to build connections and develop trust and started collaborating with them on mutually agreed issues and activities.

Opportunities for community scholars and citizen researchers

Our programme of research also actively sought enrolment of any community members who were interested in becoming more involved in the research activities. This led to our roll-out of the ‘Community Scholar and Citizen Researcher’ initiative. For our purpose, we considered community scholars to be those community-members who were interested in the research topic and provided support to us in carrying out the study without being actively involved. Conversely, citizen researchers are those community members who were directly and more actively involved in the research process. We conducted learning sessions that were open to all community members to improve their understanding of research methods and topic context as part of our community capacity building. This community capacity building approach ultimately became a strong community engagement activity for our research programme. This initiative contributed to the career progression of a number of community members. For example, we had a number of community members who progressed with careers as research project coordinators in health service organisations and not-for-profit organisations. This approach also helped us grow our research programme further.

Engaging youths through capacity building: community-centred learning

Based on cues perceived during our consultations, we developed an immigrant/racialised high school youth summer learning programme, which has been operating since 2017. Refugee and Immigrant Self-Empowerment is focused on creating mini community health and wellness champions to empower immigrant/racialised community youth. This also provides an opportunity for Cumming School of Medicine students and staff to gain community-centred learning experience. Despite the COVID-19 outbreak, we have managed to offer this programme again in 2021. We had to adapt the programme to be delivered through an online platform, and participant response has been very encouraging. This initiative proved to be a very effective community engagement tool in building trust around our activities.

Knowledge translation activities engaging the community towards trust building

We published lay articles based on our research about the barriers to healthcare immigrants face in the biweekly Bangla language newspapers. We also used social networking sites, particularly Facebook, to disseminate our work among the wider membership of the community. We successfully conducted workshops on health-related issues among the community on topics they suggested. This knowledge translation through an integrated approach has enhanced our community engagement efforts of striving to develop a trusting relationship with the community with which we wished to work. It also contributed to our acceptance in the community, which was extremely valuable for our research activities.

Conducting community-engaged research

Co-identifying the research themes

As our community engagement activities progressed, we brainstormed with our community members about what research we could conduct. The community scholar and citizen researchers functioned as a think-tank in the process. A number of research ideas were deliberated on, and we discussed our strengths, limitations, resources and possible timelines related to those research themes. We decided to focus on primary healthcare access issues faced by immigrant/racialised communities based on a combination of different factors, including perceived community needs, the research team’s strengths and limitations, and resource availability for conducting the research. We prepared to conduct a number of focus groups, which were to be followed by a community survey to identify barriers and propose solutions to overcome those barriers as voiced by Bangladeshi-Canadian community members. We have already shared our findings on the barriers to primary healthcare access raised by Bangladeshi-Canadian women14 and men,15 as well as their perceptions on possible solutions to overcoming those barriers.16 We also reported on community prioritisation of the issues they suggested we work on.17–19 Below is a summary of our understanding of the process of ensuring the community is meaningfully engaged in the research process.

Recruiting participants for the research studies

Considering the distribution of the Bangladeshi immigrant population in Calgary, recruitment strategies were formulated with feedback from community leaders and our citizen researchers. Table 1 shows the strategies we employed to recruit participants.

Table 1.

Participant recruitment strategies

| Study posters | Posted in community locations, including Bangladeshi grocery stores, restaurants, faith centres and community centres. |

| Leaflets | Distributed at community gatherings, including prayers centres, cultural events and smaller social gatherings. |

|

|

| Advertisements | Placed in a local Bengali newspaper. |

| Social networking site |

|

| Crowdsourcing of data through online survey platform | We initiated an online platform for the survey component and used the above approaches to disseminate the invitation to participate in the online survey. |

| Snowball method |

|

Collaboratively making sense of data

As members of our research team, the Bangladeshi-Canadian community-based citizen researchers have been involved in the community engagement, participant recruitment and transcription and translation processes related to our study. They were also engaged during the analysis process to contextualise the codes and themes arising from the focus group discussions, as well as writing the manuscript.14–16 We also made sure to conduct member checking by reaching out to the community members who agreed during the focus group discussions to be contacted for this purpose. Our community prioritisation survey data were also analysed and contextualised through actively involving the community-based team members.19 The benefits of involving citizen researchers were multifold. Proper interpretation and contextualisation of the research data were ensured. They also developed some methodological skills through their involvement, for which they were very appreciative. Additionally, they were instrumental when we took the findings to the community, especially in terms of reach, acceptance and further engagement.

Taking the results back to the community

Our study results were analysed and published over the course of the last couple of years. We developed a number of infographics and summary posts to disseminate our findings. We created materials that are culturally appropriate and in the ethnic language. One interesting realisation we had during these activities is that social networking sites are an effective tool for disseminating or broadcasting, but they are not as effective for engagement. Active interaction with the community through different means seems to be crucial for significant community engagement. During the current pandemic, a time of social isolation, our activities focused more on proper information sharing regarding COVID-19-related issues such as infection spread, hygiene, social distancing, misinformation and disinformation, vaccines and vaccine hesitancy, and other contemporary issues. Though these activities were not directly related to the research we were conducting, they helped us to continuously engage with the community.

Beneficial influence of social capital gained through community engagement

An interesting realisation during this phase of research was that, for both the focus group discussions and survey, most of the recruitment was accomplished through the snowball approach. The open invitation-based recruitment did not yield much success, but the snowball method was extremely successful. This might point to the lack of willingness of immigrant/racialised communities to participate in research. That said, we may need to explore systemic factors and other reasons for low participation. It is important for communities to actively participate in research that has the possibility to empower them. Our continuous community-engagement and relationship-building activities were successful. During the snowball recruitment activities, we came to realise that the social capital we gained through our meaningful and continuous community development activities was the main reason respondents engaged positively.

Role of the community scholar and citizen researchers as a connector with the community

The community scholar and citizen researchers played a major role in our research. Apart from supporting the participant recruitment and survey dissemination, citizen researchers also contributed as translators and in preparing the transcripts of focus group discussions. They also were instrumental in contextualising our analysis and contributed to our manuscripts as coauthors. We tried our best to compensate them through funds, networking, capacity building and assisting in their career trajectory. The community scholars were very helpful to act as our sounding board as the discussed our results with them across different phases. We also realised an interesting aspect of involving the community collaborators in our activities, especially the study participant recruitment process. There might be a potential for social influence related power dynamics when community collaborators try to directly recruit using the snowball method. To mitigate this risk, as already described in table 1, we conducted regular sessions with our community scholars and citizen researchers about the ethics-related issues of conducting research with human subjects. This has led to a very engaging conversations on the good practice of conducting research among immigrant/racialised communities and visible ethnic minorities.

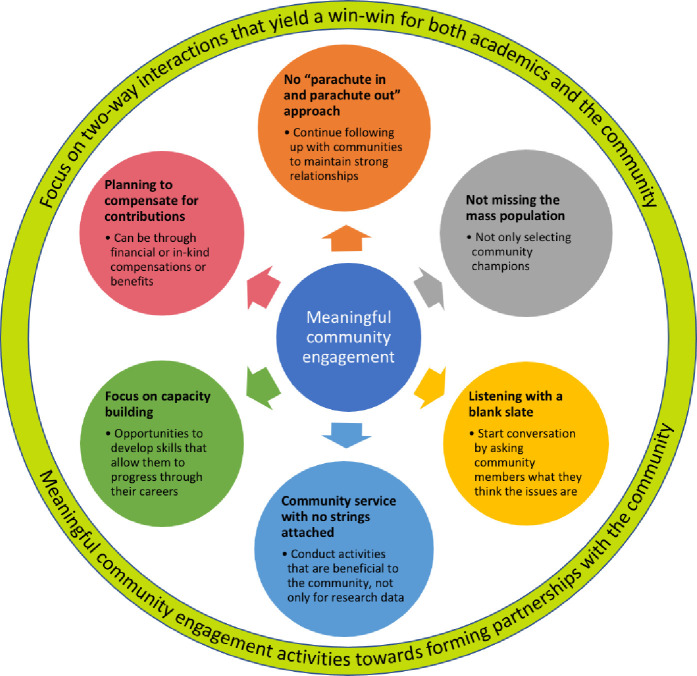

Meaningful community engagement

Through our experience, we identified a few major guiding principles of meaningful community engagement that we discuss below (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Components of meaningful community engagement.

No ‘parachute in and parachute out’ approach

During our outreach, we were informed that, in many instances, researchers enter communities to collect data after which there is little follow-up. Sometimes the communities are not even aware of any of the results that might have come from the research. This influenced the principle of continuous community engagement we adopted throughout our programme of research. We had a frank conversation with the community members that when we have the funds to pursue the research, the work will go strongly, but when we do not, our work will be of lower intensity, but we will still be doing what we can to further the research programme.

Not missing the mass population

We also strived to reach the mass population of the community. We did not want to simply obtain the check-box involvement of select community members or just partner with organisations and portray them as surrogates of the community. Rather, our activities were open to anybody who might be interested in joining us at any point in time. This approach helped us be in touch with a larger portion of the community. We implemented two approaches to reach the mass population. The first was through the community champions or influencers. We continually updated them on the progress of our work, and some were closely involved in the research process itself. Their buy-in of our work helped improve the perspectives general community members had concerning our initiatives. Second, we also took an active approach in disseminating information about our research. We proactively used social networking sites and ethnic media to advertise our events and activities. This also kept our work visible to the general community members.

Listening with a blank slate

During our engagement process, we learnt a very important lesson. Throughout our community consultations, whenever we started by summarising previous research and suggesting what the problems might be, we lost people’s attention. When we started the conversation by asking them what they felt the issues were, the conversations were more engaging. After this realisation, we adopted a listening campaign where the conversation commenced with a blank slate. We adopted a curiosity-based rather than an assumption-based approach.

Community service with no strings attached

Our knowledge translation and community capacity-building activities, such as holding community workshops, having a presence at festivals or conducting youth learning sessions, immensely helped us develop a relationship with the community, particularly because these activities were not specifically related to our research activities. With research activities, there is a notion that the researchers are collecting data from which they alone are benefiting. Engaging in activities that were not directly related to research helped us create a more trusting relationship with the community.

Focus on capacity building

Our focus on community member capacity building attracted a number of community members to the Community Scholar and Citizen Researcher initiative and helped us develop and strengthen our inroads with the community. As we have already acknowledged, the community scholar and citizen researchers were instrumental in participant recruitment, which helped us conduct the research component successfully. The Community Scholar and Citizen Researcher initiative is a dynamic and continuous progression. Some members have moved forward with new careers and new members have joined in the process, but one highlight is that previously active members have now become enthusiastic champions of the research programme.

Planning to compensate for contributions

The possibility of arranging to compensate the community’s contributions is also important. This can be accomplished through capacity building, as mentioned above, in-kind contributions as mutually agreed on or financial benefits to the community members. In many instances, researchers might not have sufficient resources to permit financial compensation. However, community members also may not want to participate in research studies if compensation is not available. Ideally, however, in a well-designed programme of research that ensures the community is continuously engaged through various community-centred activities, the inability to compensate should not impact the research process. We felt that the trustworthiness of the programme of research always mobilises the community towards supporting that programme’s activities.

Working from engagement towards partnership

The most important realisation for us through this journey was that one-way knowledge translation is not the way to mobilise a community. Community engagement must involve not only conversing with the community but doing something together. Whatever is undertaken must also yield a tangible benefit for community members. Creating capacity within the community not only increases engagement, it also helps them realise the hard-to-see impact of our work and makes the partnership sustainable. When conducting community engagement, we need to ensure we understand what the win is for the community. Only a win-win scenario can move everyone forward.

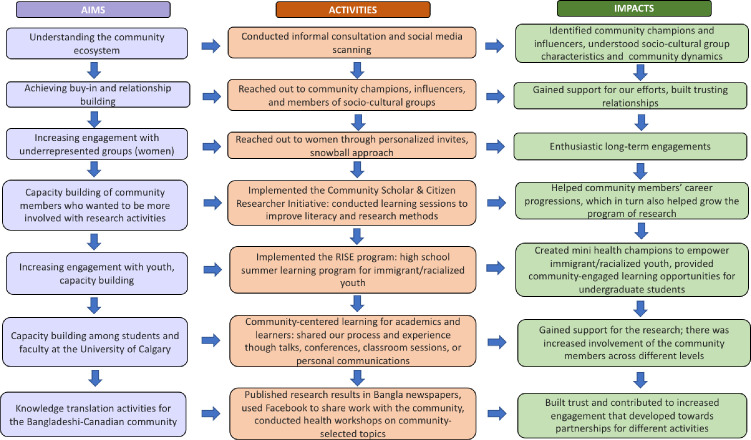

This article describes our experience of a successful and meaningful engagement with an immigrant/racialised community (Bangladeshi-Canadians) as a case study for our community-engaged research programme. Our exploration of working with the community fascinated us. We were able to develop a community-engaged research strategy (figure 3) on the issue of equitable healthcare access by the community members. Through meaningful community engagement activities since 2014, we have been coidentifying research priorities towards solution-oriented research.

Figure 3.

Community-engaged research strategy.

Our research team also had embedded positionality in the Bangladeshi immigrant community. The research leader (TCT) belongs to that community. Also, the academic home of the research team is the Family Medicine and Primary Care Research Department in the Cumming School of Medicine at the University of Calgary. In building a community-engaged programme of research, we commenced engagement with the Bangladeshi community, where we had relatively easier access to different levels of the community. A few members of our author group (NR and MAAL) became involved as the programme developed over time. The research leader had the basic understanding of community dynamics. It was easier for us to start with informal consultations with community members because of our similar language and cultural advantage. Interestingly, however, our overall understanding of the community ecosystem was more incomplete than we had thought, and we needed to work on that extensively. Being a member of a community, organisation, or group does not automatically mean the researchers understand or have access to all aspects of the community, organisation, or group for research purposes. From our experience, we now realise that community engagement is not only about knowing, connecting with, and discussing with people—rather, there need to be meaningful activities where community members can participate as equals. Activities towards gaining trust and developing working relationships at the community level for conducting research proved to be very important. Also, it was very satisfactory and fulfilling for us to be able to contribute towards community development in whatever small way we could make it happen. Though we had theoretical knowledge of participatory research approaches, the biggest learning came from the work of ‘making it happen’. This reflection manuscript presents our understanding of the ‘making it happen’ part, which we presented as ‘Meaningful Community Engagement’.

Conclusion

Immigrant/racialised communities need to be mobilised through research and practice domains that can help guide change from the conventional top-down approach to a sustainable and replicable community-driven approach for research and priority setting. The goal is to facilitate the coproduction of knowledge and its implementation by including the community in the policy-related decision-making process that is essential for developing culturally appropriate solutions. In this article, we have reflected on a research approach to meaningfully engage immigrant/racialised communities in community-based research. This is an integrated approach for meaningful community engagement that fosters community involvement and builds on developing community capacity to actively contribute to the research. Though this reflection focuses on our work with one specific community, we also have started engaging with the Latino, Arab, South-East Asian and black communities. Our learnings from the community-engaged research described in this article can also help guide research with other communities to address a range of issues, such as employment, social integration, labour market integration and more.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the wholehearted engagement and gracious support we have received from the Bangladesh-Canadian community members in Calgary. Also, we appreciate the compassionate encouragement and assistances we have received from all the socio-cultural organizations belonging to this community. We would also like to acknowledge the support from our academic peers and institutional leaderships towards this community-engaged program of research.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Twitter: @drturin

Contributors: TCT, NRu and MAAL conceived the study idea. TCT, NC, NRu, NRa and MAAL conducted the study. TCT, NC and NRu drafted the manuscript. NRa and MAAL critically reviewed the manuscript and provided important perspectives as community member researchers.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: The authors do not have any competing interest to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

There are no data in this work.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.Rasanathan K, Montesinos EV, Matheson D, et al. Primary health care and the social determinants of health: essential and complementary approaches for reducing inequities in health. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011;65:656–60. 10.1136/jech.2009.093914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Health Canada . Canada’s health care system. How health care services are delivered, 2021. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-system/reports-publications/health-care-system/canada.html

- 3.Kalich A, Heinemann L, Ghahari S. A scoping review of immigrant experience of health care access barriers in Canada. J Immigr Minor Health 2016;18:697–709. 10.1007/s10903-015-0237-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed S, Shommu NS, Rumana N, et al. Barriers to access of primary healthcare by immigrant populations in Canada: a literature review. J Immigr Minor Health 2016;18:1522–40. 10.1007/s10903-015-0276-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chowdhury N, Naeem I, Ferdous M, et al. Unmet healthcare needs among migrant populations in Canada: exploring the research landscape through a systematic integrative review. J Immigr Minor Health 2021;23:353–72. 10.1007/s10903-020-01086-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Government of Canada . Immigration and ethnocultural diversity: key results from the 2016 census, 2017. Catalogue no 11-001-X, 2017. Available: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/rt-td/imm-eng.cfm

- 7.Vang ZM, Sigouin J, Flenon A, et al. Are immigrants healthier than native-born Canadians? A systematic review of the healthy immigrant effect in Canada. Ethn Health 2017;22:209–41. 10.1080/13557858.2016.1246518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonald JT, Kennedy S. Insights into the 'healthy immigrant effect': health status and health service use of immigrants to Canada. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:1613–27. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe . Community participation in local health and sustainable development: approaches and techniques. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2002. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/107341 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-Based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health 2010;100 Suppl 1:S40–6. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canadian Institutes of Health Research . Guide to knowledge translation planning at CIHR: integrated and end-of-grant approaches, 2015. Available: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/45321.html

- 12.Chen E, Leos C, Kowitt SD, et al. Enhancing community-based participatory research through human-centered design strategies. Health Promot Pract 2020;21:37–48. 10.1177/1524839919850557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jull J, Giles A, Graham ID. Community-based participatory research and integrated knowledge translation: advancing the co-creation of knowledge. Implementation Sci 2017;12:1–9. 10.1186/s13012-017-0696-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turin TC, Rashid R, Ferdous M, et al. Perceived challenges and unmet primary care access needs among Bangladeshi immigrant women in Canada. J Prim Care Community Health 2020;11:215013272095261. 10.1177/2150132720952618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turin TC, Rashid R, Ferdous M, et al. Perceived barriers and primary care access experiences among immigrant Bangladeshi men in Canada. Fam Med Community Health 2020;8:e000453. 10.1136/fmch-2020-000453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turin TC, Haque S, Chowdhury N, et al. Overcoming the challenges faced by immigrant populations while accessing primary care: potential solution-oriented actions ddvocated by the Bangladeshi-Canadian community. J Prim Care Community Health 2021;12:215013272110101. 10.1177/21501327211010165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turin TC, Lasker M, Ferdous M, et al. Knowledge to action strategy development town-hall meeting with Bangladeshi-Canadian community: identifying primary care access research priorities through community involvement. 46th North American Primary Care Research Group (NAPCRG) Annual Meeting 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ehsan K, Lasker MA, Turin TC. Identifying and prioritizing barriers for mitigation through meaningful community engagement. Mobilizing Knowledge on Newcomers Symposium 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turin TC, Haque S, Chowdhury N, et al. Community-Driven prioritization of primary health care access issues by Bangladeshi-Canadians to guide program of research and practice. Fam Community Health 2021;202. 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000308. [Epub ahead of print: 20 Jul 2021]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.IAP2 . IPA2 spectrum of public participation, 2018. Available: https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.iap2.org/resource/resmgr/pillars/Spectrum_8.5x11_Print.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

There are no data in this work.