Abstract

Many institutions of higher education have implemented workshops for hiring committee members to familiarize them with the pernicious effects of implicit bias and how to counteract them. Unfortunately, the enthusiasm for implicit bias trainings is not matched by the evidence for their effectiveness. Recognizing the difficulty of removing entrenched biases and the potential for trainings to backfire, we introduced the role of equity advocate (EA) at one institution. EAs are trained volunteer faculty and staff members who serve on search committees outside their home departments to identify behaviors and judgments that might have a disparate racial effect in hiring. We conducted focus groups to document the perspectives of both EAs and non-EA search committee members who completed a cycle of academic hiring. Search committee members credited EAs with helping to mitigate bias by questioning their assumptions and introducing standardized tools for evaluating candidates. By contrast, EAs reported a more contentious relationship with the rest of the search committee and expressed less confidence that the process was free from bias. Both groups agreed that the EAs added valuable race-conscious equitable practices, and untrained committee members identified ways they could apply the lessons of bias reduction in other parts of their professional roles. Our study provides evidence for how to engage all faculty and staff members in sustainable, equity-minded efforts.

Keywords: Faculty search committees, Implicit bias, Equity advocate, Equity-mindedness, Hiring

Introduction

Faced with the seemingly intractable problem of diversifying the faculty, universities have long implemented an array of programs to enhance recruitment and retention of candidates from minoritized groups (Taylor et al., 2010). One of the most prominent explanatory frameworks in these efforts has been the academic pipeline metaphor (Justice, 2009; Stanley et al., 2007; Wilson et al., 2018). According to this theory, expanding the supply of graduate students of color and plugging “leaks” in the pipeline to faculty positions will make it easier to change the demographics of the professoriate. Pipeline thinking has spurred the launch of mentorship and professional development programs to prepare graduate students for academic careers. Yet, decades-long trends in graduate student enrollment toward greater representation of women and people of color have not led to a corresponding increase in their representation among faculty (Gibbs et al., 2016; Tuitt et al., 2007).

Instead of looking to increase the supply of qualified candidates, some universities have turned their focus to cognitive flaws in the decision making of institutional gatekeepers. Because faculty hiring tends to be decentralized among ad hoc search committees without standardized procedures, judgments about applicants may be clouded by implicit bias. Social psychologists have explained implicit bias as automatic associations human brains make based on media portrayals and cultural norms, which come to be calcified into stereotypes (Banaji & Greenwald, 2013). In faculty hiring, these stereotypes designate who is considered an acceptable faculty member and can erect significant barriers for candidates whose sex, race, or intellectual interests fall outside the norm (Liera & Ching, 2019). University leaders have responded by implementing workshops for search committee members to familiarize them with the pernicious effects of implicit bias and how to counteract them (Sekaquaptewa et al., 2019; Shea et al., 2019).

Unfortunately, the enthusiasm for implicit bias trainings is not matched by the evidence for their effectiveness. Psychology researchers conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis of close to 500 studies designed to rewire automatic associations to mitigate bias. They found no data to indicate that interventions designed to affect implicit bias changed behavior (Forscher et al., 2019). More troubling is research indicating that implicit bias trainings may backfire by making participants complacent or even hostile to diversity efforts (Dobbin & Kalev, 2018). If implicit bias among search committee members limits the success of candidates of color, and if short-term workshops do not mitigate entrenched mental schemas, how can university administrators advance their goal to diversify the faculty?

As a possible solution, we introduced the role of equity advocate (EA) at one institution. We recruited and trained volunteer faculty and staff members to serve on search committees outside their home departments. Their role was not to instruct colleagues on implicit bias, but to serve as guardians of a fair process. EAs identified behaviors and judgments that might have a disparate racial effect in hiring without seeking to alter committee members’ mental models. While studies are emerging to document how EAs engage in promoting equitable search practices, it is not yet clear what impact introducing outside members trained in race-conscious practices has on the “untrained” search committee members. In this study, we document the perspectives of both EAs and non-EA search committee chairs and members who completed a cycle of academic hiring. The results will contribute to understanding how to engage all members of a university community in equity-minded work.

Theoretical Background

Academic hiring invests considerable authority in search committees to recruit, screen, and evaluate candidates for faculty positions. Members of these committees are selected for their content expertise rather than their knowledge of human resource management, resulting in the elevation of personal preferences over rigorous application of consistent criteria (White-Lewis, 2020). Committee members at predominantly white institutions may be committed to diversifying the faculty, but they also unquestionably subscribe to beliefs that value a narrow set of qualifications that candidates who identify as Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) are less likely to possess. Through every step of the process from writing the position description, vetting curriculum vitae, and interviewing finalists, faculty search processes center values associated with whiteness so that anyone from outside the majority frame is cast as deviant (Sensoy & DiAngelo, 2017; White-Lewis, 2021).

A logical response from many academic institutions has been to train search committee members to understand how implicit biases structure decisions and become aware of their own narrow lenses (Fraser & Hunt, 2011; Russell et al., 2019). Scholars who conducted a systematic review of bias in faculty hiring drew on the insights of behavioral economics to suggest how bias reduction “nudges” can slow committee members’ automatic judgments and introduce space for more deliberate thinking (O’Meara et al., 2020). Nudges may support better decision making, but they still rest diversity goals on reshaping individual mindsets. Leveraging implicit bias as a mechanism for sustainable change ignores the structural inequities that perpetuate the status quo in academia (Pritlove et al., 2019).

Griffin (2020) proposes a shift in theoretical approach from diversity to equity. Under the diversity umbrella, colleges and universities set numerical goals for increasing the representation of people of color on their faculty. They tend to close the perceived gaps by seeking to “fix” the individual graduate students or faculty members with deficiencies. For members of the minoritized group, this could come across as blame for the very problem that disadvantages them. For faculty members asked to participate in training, the message may trigger status anxiety and opposition (Dover et al., 2016). By contrast, an equity-minded approach focuses attention on institutional policies and practices that inhibit full inclusion. As Bensimon (2018) argues, equity-mindedness starts from the assumption that the structures of higher education reproduce racial inequality and that dismantling them will require system-level changes. Where faculty hiring is concerned, the built-in preference for white candidates becomes entrenched through exclusionary position descriptions, limited recruitment networks, and narrow definitions of quality (Bhalla, 2019; McNair et al., 2020: pp. 40–41).

The equity advocate is a voting member of the faculty search committee whose primary function is to call attention to and correct the practices and policies in the hiring process that unfairly disadvantage candidates from minoritized groups. Inspired by similar programs at Oregon State University (McMurtrie, 2016) and Montana State University (Burroughs, 2017), the EA participates in formulating the position description, recruiting candidates, screening materials, interviewing finalists, and making the final recommendations. At each stage, they practice equity-mindedness by raising race-conscious questions about which candidates committee decisions will benefit and suggesting consistent templates to limit bias. The EA model is premised on research showing that implicit biases exert a particularly strong influence on candidate selection when criteria are fuzzy and the process unstructured (Dovidio et al., 2016). Attempts to suppress implicit bias rarely succeed in achieving durable change (Lai et al., 2014) and may even strengthen underlying stereotypes (Monteith et al., 1998). Using EAs for faculty searches accepts that entrenched biases will remain but their effect on decisions may be mitigated through consistent application of fair practices.

In a recent study, Liera (2020a) interviewed faculty members at a private college who underwent training as EAs and subsequently served on search committees. They shared that the institutional legitimacy of the role gave them authority to talk about race and to challenge existing practices, but not without resistance from other members of the search committee. Our study extends Liera’s analysis by including the perspectives of both the EAs and the search committee members who did not receive special training. Adding an EA to a search committee avoids the potentially negative outcomes of implicit bias training, but we know from studies with white faculty that any talk of race can potentially provoke anxiety (Sue et al., 2009). We analyzed experiences from both sides to discern whether EA participation produced unintentional consequences that might undermine the overarching goal of removing barriers to hiring more faculty of color.

Method

Researchers used a narrative study design (Lochmiller & Lester, 2017) and conducted separate, semi-structured focus group interviews with search committee members and EAs. Focus groups, as opposed to one-on-one interviews, were leveraged, when possible, to promote social cohesion and allow search committee members and EAs to share opinions, ideas, and perceptions, while allowing researchers to collect data from multiple individuals simultaneously (Onwuegbuzie et al., 2009).

Participants

The site for this study was MGH Institute of Health Professions, a not-for-profit health professions graduate school in Boston, Massachusetts, called here “the Institute,” with entry-level and post-professional programs in genetic counseling, health professions education, nursing, occupational therapy, physical therapy, physician assistant studies, rehabilitation sciences, and speech-language pathology. At the time of the study, the school enrolled 1,756 full-time equivalent students, 32% of whom identified as BIPOC. The faculty ranks included 118 full-time equivalent faculty members, 10% of whom identified as BIPOC. In 2019, in direct response to the Institute’s strategic priority to nurture a diverse and inclusive community, the Office of Justice, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion opened to better coordinate efforts to provide students, staff, and faculty with the skills to better serve marginalized communities and to address existing inequities (Truong & Martinez, 2021). The Institute adopted the EA model to address structural issues with the faculty recruitment and hiring process that might hinder the strategic priority. In fall 2019, a team of faculty, administrators, and human resource staff hosted an open information session to introduce faculty and staff to the EA role.

Equity Advocate Training

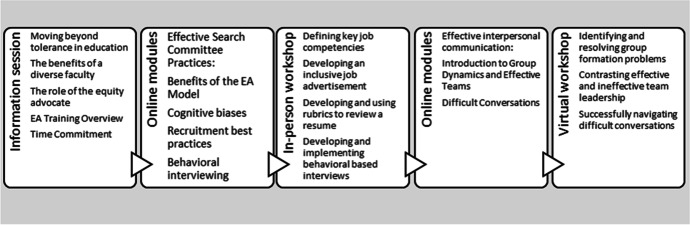

The aim of adding an EA to a search committee was to ensure a fair, consistent process that minimized the impacts of cognitive and structural biases. External to the hiring department, EAs contributed to position announcement development, recruitment, screening, interviews, and reference checks as well as explored assumptions, norms, and practices that might hinder full consideration of each candidate’s credentials. Training included eight hours of both online and in-person activities, covering both human resource practice and interpersonal dynamics (see Fig. 1). Online self-paced modules were designed to be completed asynchronously in advance of two in-person sessions. The synchronous training comprised two two-hour sessions to allow for the application of concepts learned online. The second in-person session had to be transitioned to a virtual platform due to the Covid-19 pandemic and campus closure. Twelve participants (eight staff and four faculty members) completed both the online modules and in-person/virtual training sessions and were qualified to serve as EAs.

Fig. 1.

Equity training overview

Recruitment

In the fall of 2020, four search committees across the Institute were convened to make recommendations to fill one staff and three faculty positions. Search committee chairs were informed that an EA would be added to the committee and given information about the EA’s roles and responsibilities. The staff position required a candidate with an advanced degree who would work closely with faculty, so the Institute leaders decided to include an EA on that committee as well. Across the four search committees, seventeen faculty and staff and one student served as non-EA members. Two of the 18 search committee members had completed the EA training, though did not serve in that capacity on the committees. Four EAs (three faculty members and one staff member) were recruited from the pool of qualified EAs to serve on the committees. EAs were intentionally matched to a search committee that was outside of their home department in an attempt to decrease intradepartmental power dynamics. The assumption was made that EAs would have more autonomy to call attention to bias with search committee members from outside of their home department. After the conclusion of the four searches, researchers used purposeful sampling to recruit participants for two sets of focus groups: the 18 non-EA search committee members were invited to participate in one set, and the four EA search committee members were invited to the other. The study was approved by the Institute’s Institutional Review Board.

Data Collection

The authors developed two semi-structured interview protocols for each of the groups (see Appendix). Questions explored search committee members’ and EAs’ experiences before, during, and after the search. Search committee members were asked to reflect on what difference adding an EA to the search committee made and to offer examples of how the EA affected committee decisions. EAs were asked to reflect on examples of bias in the search committee process and how they were or were not able to call attention to bias. Additionally, EAs were asked about how the EA training contributed to the performance of the EA role. Focus group interviews lasted a maximum of one hour and were facilitated by two of the authors (a moderator and assistant moderator) over the Zoom platform. Both the moderator and assistant moderator took field notes during the interview.

Data Analysis

Researchers applied constant comparison analysis to the focus group data and interviewer field notes (Onwuegbuzie et al., 2009). Two authors coded search committee interview data, and the other two authors coded EA interview data. Authors developed a priori codes based on the research questions and the role of the EA (Elliott, 2018). Examples of a priori codes included: bias, equity, knowledge, skills. However, the authors also used open coding to allow new codes to emerge from the data analysis. The authors completed the first cycle of coding using descriptive coding independently. After a second cycle, the coding teams met to collapse codes into pattern codes, which formed the basis of the data-driven themes.

Trustworthiness

To increase credibility, researchers leveraged both researcher and data triangulation as well as peer debriefing and an audit trail (Guba, 1981). Each step of the data collection and analysis included at least two of the researchers. While pairs of researchers were responsible for analyzing either search committee or EA focus group data, the researcher pairs presented and defended their analysis to the research team. All research materials were kept in a central location, which produced an audit trail that allows for the study process to be replicated. While this research used purposeful sampling, which may limit transferability of findings, the descriptive data of the context, participants, and instrumentation is intended to increase the transferability of findings. Finally, the authors acknowledge their roles as research instruments in the data collection and analysis process. All four authors are doctorally prepared with experience in qualitative research methods.

Results

Of the 18 total non-EA search committee members, 12 agreed to participate in a focus group. They included seven faculty, four staff members, and one student, all of whom chose one of three focus group times based on their availability. All four equity advocates who served on a search committee in the fall consented to participate in the study. Three joined one focus group, and the fourth participated in a one-on-one interview with the corresponding author. In focus groups conducted without the equity advocates, committee members from different searches reflected on the impact of the presence of equity advocates. Their comments coalesced around two themes related to their positive perception of how the EAs’ participation helped mitigate bias: raising awareness and standardizing practices. As evidence of the durability of the EAs’ insights, they also shared how they applied the lessons of more equitable searches to other parts of their roles. Data analysis of the focus group and interview with the EAs revealed a different set of perceptions about the search process. Two themes emerged about the resistance they met in carrying out their role to disrupt bias: proving their worth and unbiasing the familiar.

Search Committee Members’ Themes

Raising Awareness

For many search committee members, the mere presence of an EA awakened them to the potential for inequity. Except for one committee chair, all veteran search committee members expressed that, in retrospect, previous searches had seemed overly informal. One participant said about previous searches: “It always struck me as strange the lack of consistency. It seemed very much at the discretion of the hiring manager.” Another experienced search committee member reflected about earlier searches, “They weren’t intentionally inequitable. They were disorganized. A lot of unexamined practices were able to take place.” By contrast, having a colleague with the designated role of suggesting ways to enhance equity kept everyone’s mind on the process. One committee member remarked, “It was just the consciousness of having someone there. It made me think about the questions I would ask, knowing she [the equity advocate] was there.” Another committee member echoed the observation: “I think one of the things it [the equity advocate] helped us do is just be more aware. It’s not like the person had to say, ‘Things are going crazy here.’”

That EAs came from outside the hiring department heightened their ability to raise committee members’ awareness of bias. Three members of the same search committee agreed:

It was a help that they were from a different field. They didn’t get caught up in the jargon. They were just looking at the process, was it fair. I think it worked.

I completely agree. It’s optimal to have someone from outside the discipline. It’s helpful to have a broad lens.

I agree with that as well. It’s nice to have someone from outside. It keeps everyone accountable.

A participant in a different focus group came to the same conclusion, observing, “She brought outside perspective that kept us honest. She asked very obvious questions, and it served as a really good double check.” Even in search committees where other members felt familiar with bias-mitigating practices, a designated equity advocate added another layer of accountability. “Having someone with that priority was valuable even though others had that terminology. It was a delegation of that role.” Because the EA came with a specific charge, it allowed the other search committee members to focus on their content expertise, knowing that someone else was guarding the process.

Standardizing Practices

Another way that equity advocates raised awareness of potential bias was by introducing standard human resource practices that encouraged a more thorough and deliberate process. The EAs’ influence was particularly visible in creating templates for interview questions. A search committee chair reflected:

The involvement of the equity advocate has been huge and sharpened our awareness of all the ways we have been unaware of what we should have been doing. For instance, we were asking different questions of candidates for the same position. It allowed implicit bias to seep into the interview process.

On another committee, the EA guided the committee members to link every interview question to an element of the job description and then ask the same set of questions of every candidate. The committee member praised the improvement: “It’s nice to have it [the interview protocol] written in front of you. It’s easy to free form otherwise. It really got a lot of rich information from our applicants.”

Despite the overall appreciation for the improvements suggested by the EA, many search committee members could not identify a specific decision that resulted from the EA’s intervention. The impact was more generalized to raising reminders of how the committee was ensuring fairness for candidates of different races and other identity markers. One exchange between members of two different search committees illustrated how the EAs’ most significant contribution was to steer them toward consistent application of criteria:

I don’t recall a specific decision that was the result of her questions, but her questions encouraged more conversations about screening someone out based on something we read in the resume. Sometimes it was bringing our attention to the job description.

I would agree with that. She kept us centered on it. We would have a good ten-minute discussion and then, “Are we thinking this?” It was nice to have one person paying attention to it.

Some search committee members observed that the additional questions and templates that the EAs introduced slowed the hiring process. They acknowledged that going more slowly was ideal for ensuring equity, but, in practice, committees often felt pressure to select candidates quickly to fill urgent teaching gaps.

Application

Although a few search committee members acknowledged not knowing at first that one of their colleagues was serving as an EA, in the end, all the focus group participants praised the EA for helping them think and act more intentionally to promote equity. Tellingly, search committee members absorbed the lessons about bias and applied them to other aspects of their professional role. Many participants drew a direct connection between the benefits of more equitable faculty searches and more inclusive learning environments. Two colleagues shared examples of how the focus on minimizing bias has improved their teaching:

It’s helped me in the classroom, being cognizant of my own biases. I’m not looking at everybody the same. I try to individualize.

I agree with that. After the equity advocate, I pay more attention to questions my students ask and how I answer them.

In a different focus group, a search committee participant saw working with the EA as part of “a larger process around being a faculty member who can contribute in many ways to creating a more diverse, equitable, and just Institute.” Others agreed that the same principles of equity could enhance decisions around admissions, curricula, and promotion criteria.

Equity Advocates’ Themes

Proving Their Worth

EAs voiced that they had to prove their worth to the rest of the search committee, which at times felt like an exclusive club. Unlike most search committee members, few EAs had significant experience with faculty hiring before taking on their role and, by design, they came from outside the hiring department. They described having to earn the trust of their fellow committee members by assuring them that they were not a surrogate for administrators. As one EA put it:

There was some rockiness in the beginning. They had to overcome the idea that I wasn’t looking to report back on anyone whether they had unfair practices. I’m not a spy for [leadership] with negative information. I’m no expert at this. I took the training, I’m just another set of eyes. I’m not in that department, so it’s easier for me to look at things objectively.

It did not help the EAs’ integration into the search committees that their roles could be difficult to define. In an exchange, two EAs concurred on the ambiguity of whose point of view they represented:

It didn’t occur to me to introduce myself in that role. I was there also representing the faculty. I felt like I was doing most of my EA stuff behind the scenes.

I struggled if I should be wearing two hats. Going into it I anticipated more up-front conversation, which didn’t happen until after we had reviewed applications.

EAs revealed that search committee chairs varied in how they introduced the EAs and their roles. Some chairs made clear to committee members at the outset how the EAs would contribute to the search, while other chairs never singled them out for their unique skills. EAs who were staff members rather than faculty members seemed to avoid the problem of invisibility. One EA commented, “I have an easier time stepping out of my comfort zone if I don’t have a close relationship with the people.” Because there was no risk of being mistaken for content experts, staff members serving as EAs could be more easily recognized as bias disrupters. Of course, staff members then shouldered the added burden of proving their worth in a process usually reserved for faculty members.

Unbiasing the Familiar

Once the search process got underway, EAs observed potentially exclusionary practices that committee members did not question. At several stages in the screening and interviewing, they noted biases related to gender, age, and level of experience that might erect barriers for candidates who did not fit the status quo. One EA pointed out that wording in a proposed position description could deter certain applicants from seeing themselves as qualified:

They wanted to put on the job description “PhD in a relevant field.” I said, “What does relevant field mean?” They said it could be anything. So, I said let’s scratch “relevant.” If it means nothing, take it off. We got more specific with that one, so I was happy.

Another EA underscored the experience of helping the committee interrogate their assumptions: “We thought about age bias quite a bit—someone fresh out of a graduate program versus someone with more experience teaching. We talked about that quite a bit and asked where the assumptions were coming from.”

Other EAs felt that some committee members were more concerned with personality and fit rather than objective criteria. One participant noted about colleagues on the search committee: “It seemed like a struggle to get them to recruit more people to the position once they already had a couple [of candidates] they knew would be a good fit.” Another EA reflected about the list of two finalists, “The search committee talked about the likeability of one candidate. The second candidate came across as cold. I felt like the second candidate wasn’t pursued further because she was ‘difficult.’” Hearing that story, an EA from a different search recalled that her committee had conversations about candidates’ expected salary range and what role that should play in the screening process.

Adding to the challenge of introducing more objective criteria was the urgency of the process. EAs expressed that committees felt pressure to fill open positions and were more concerned with losing viable candidates than following all the steps to make the process equitable. In one exchange, two EAs agreed:

It was so fast moving, and they were looking to fill the position as soon as possible, so they weren’t willing to take more time.

We did struggle with the timeline. We wanted to be purposeful. The committee knew that things in their field move quickly, this fear of losing people because we were taking too long versus not missing people. At what point do we say, “This is it?”

Another EA later echoed the feeling: “The train had left the station, I got swept up in it. I wish I had paused more.”

In the end, the EAs felt mostly satisfied that they had been able to enhance the equity of the hiring process. Even if not every suggestion of theirs was adopted, they believed they were heard and given full consideration. One EA believed that, after spending so much time with the other members of the search committee, posing difficult questions became easier, and the committee became more grateful for the opportunity to consider outside perspective. As a sign of the enduring commitment to equity-minded work that the EA engendered, one search committee asked their assigned EA to stay on after the position had been filled to help them develop more uniform materials for evaluating CVs and asking behavioral-based interview questions in future searches.

Discussion

Conducting focus groups and interviews separately with trained equity advocates and untrained search committees highlighted differences in perceptions about promoting equity in faculty hiring. Even with no EAs present to hear them, the untrained search committee members expressed appreciation for the contributions of the EAs. They saw themselves as invested in fairness and committed to diversifying the faculty. Although not positioned as teachers about bias, the EAs helped raise everyone’s awareness of how simply repeating existing practices can allow bias to reproduce. Search committee members credited EAs with helping to mitigate bias by questioning their assumptions and introducing standardized tools for evaluating candidates. If the EAs’ interventions did not always lead to a different course of action, committee members felt pleased that they had considered their decision carefully with the implications for equity in mind. No search committee member voiced criticism of the EAs or the emphasis on equity that they brought to the process.

By contrast, EAs reported a more contentious relationship with the rest of the search committee. Conflict was most likely at the outset of the committee’s work, when some members questioned the EAs’ motives. It was unclear to the full committee if the EAs represented themselves, their departments, the administration, or a combination. The hiring cycle under analysis was the first at the Institute to include EAs, which might have contributed to the initial wariness. It also did not help that the EAs were still forming a clear picture of their roles and were assigned to their committee as a single advocate. That none of the untrained search committee members mentioned the initial rockiness that the EAs perceived could reflect the EAs’ oversensitivity to joining an already established group of colleagues. The pattern also fits the description of “aversive racism,” in which people are outwardly sympathetic to the goal of racial equity but still harbor negative implicit bias about racially minoritized groups (Dovidio et al., 2016). Aversive racists see themselves as non-prejudiced and, therefore, object to any accusation that they are influenced by bias. EAs’ may have been detecting the anxiety that some people feel when they suspect they will be accused of racism.

The other significant difference emerged in contrasting views of equitable practices during the search. For untrained committee members, the addition of EAs and the templates they provided for evaluating CVs and conducting interviews improved an inconsistent process. They expressed satisfaction that the changes encouraged by the EAs led to a fair outcome. The EAs were not so confident that the process was free from bias. Though improved from their previous, more casual state, search committee practices replicated some of the same failings that have been identified in the literature (Bilimoria & Buch, 2010). Committee members, according to the EAs, used language in job descriptions that might send unwelcoming signals to certain candidates. They weighed heavily criteria like years of experience that were not specified in the job description. Committee members valued subjective measures like fit, quickly coalescing around certain candidates who met a preconceived profile. This tendency to come to a conclusion and then disregard contradictory evidence, known as confirmation bias, has been well documented in the psychological literature and clouds decision making in fields as diverse as medicine, criminal justice, and education (Nickerson, 1998). The imperviousness of beliefs to new evidence raises the question whether EAs shifted committee members’ underlying opinions or if they simply introduced temporary adjustments to make the process more equitable.

The two groups converged around the benefit of having EAs from a different department than the hiring unit. This agreement contradicts some universities’ established practice of attaching equity advocates from the same department or school to a search committee (Davey et al., 2021). For the untrained search committee members in our study, the EAs’ fresh perspective spurred them to justify some of their unquestioned assumptions and practices. Working with a colleague specially trained to ensure equity freed up the committee members to focus on using their disciplinary expertise to evaluate candidates’ potential for scholarship, teaching, and service. Even those members who had completed the EA training but were not serving in that capacity on their search committees expressed that it was helpful to have someone else monitoring the process because they could not maintain the cognitive effort needed to both exercise professional judgment and neutralize implicit bias. EAs also found value in their outsider status. It gave them the courage to raise difficult conversations knowing that they did not have to interact regularly with their fellow search committee members in other contexts. This perspective supports research illustrating a “culture of niceness” in academic settings that inhibits challenges to the status quo (Liera, 2020b). EAs could promote potentially disruptive efforts to advance racial equity most effectively because they did not participate in the same culture of consensus as other members of the search committee did.

The other major area of overlap between the two groups appeared in the durability of the changes implemented. Search committee members could see concrete applications of the equity-minded practices to other parts of their role. Many spoke approvingly of how the EAs showed them the influence of bias in decision making and how that insight could inform their interactions with learners. EAs also felt that their participation made meaningful and lasting changes in how searches were conducted. The absence of a backlash to adding race-conscious equitable practices suggests the advantage of training volunteer equity advocates rather than all search committee members. The research of Dobbin and Kalev (2016) demonstrates how professionals resent mandatory trainings, which often use negative messages and threats to cajole participants into shedding their biases. The EA model trains only those participants who are interested in developing their equity-minded skill set and then deploys them to engage other committee members in conversation around bias in hiring. Because they see themselves as free of prejudice, untrained search committee members welcome the opportunity to live up to their self-image.

Although EAs helped soften the unintended effects of mandatory bias training, they may have contributed to complacency around racial equity. The gap between search committee members’ satisfaction that they had eliminated bias and EAs’ documentation that many stubborn practices persisted to limit opportunity for BIPOC candidates suggested disparate levels of enthusiasm for tackling the structural roots of inequity. The connections that search committee members drew between bias in searches and other facets of their roles were limited to changes in interpersonal relations. They became more attuned to how bias impacted their judgment of student applicants as well as faculty candidates, but they did not seek to reform the way either group is recruited or evaluated. Nor could the EAs address some of the contradictions born from launching searches in response to an immediate teaching need. Many equity-minded practices require slowing down the process to deactivate implicit biases. The searches, however, seemed to develop their own momentum, leaving EAs in the lonely position of having to balance fairness with expediency. Addressing the structural inequities in how faculty positions are created and funded will require involvement from higher levels of leadership.

Limitations

Our study was affected by two sets of limitations. The first set of limitations reflects how the context of the study may have affected which participants consented to join the focus groups and what they said. The interviews’ explicit focus on diversity, equity, and inclusion might have created a selection bias in which eligible participants consented to join the study. The Institute, like peer universities, had recently adopted a commitment to antiracism. Participants who were not aligned with the commitment might have opted not to participate or joined but held back in their criticism of the EA program out of fear of being labeled oppositional. Moreover, the study was conducted during the Covid-19 pandemic when the institution was in operating in remote mode, so the interviews were conducted on the Zoom platform. The Zoom platform might have affected how the participants responded and engaged with each other, depending on their level of comfort with the technology, possibly creating an imbalance in contributions to the discussion. Another set of limitations might have impacted the searches themselves. The economic uncertainty triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic led the Institute to curtail the number of searches conducted during the intervention period compared with normal or past periods. The unusual health and economic conditions might also have affected the type and number of applicants competing for fewer open positions nationally, creating a committee dynamic that differed from searches in typical years. Despite the limitations, we were able to gain insight on the impact of being an EA as well as having an EA on a search committee. Because this was a qualitative study, our findings are context-dependent and might inform but do not extrapolate neatly to other institutional settings. The authors employed several techniques to strengthen the rigor of analysis, including independent coding followed by peer review, triangulation of data, and reflection on biases.

Conclusion

Our results support the equity advocate model as an effective way to minimize bias in the faculty search process that could hinder the success of BIPOC candidates. From the wording of the position description to recruitment efforts, CV screening, and interview questions, untrained search committee members allowed subjective assumptions to influence their decisions. Their implicit biases favored applicants whose institutional affiliations, teaching experience, and personalities matched committee members’ own. Despite outward agreement with the goal of attracting and retaining BIPOC faculty members, search committee members were mostly unfamiliar with standard human resource practices designed to ensure fairness. When specially trained EAs joined the search committees, they raised members’ awareness of the potential for bias and introduced consistent criteria and interview questions so that all candidates could be evaluated fairly.

As previous studies have shown and our findings confirm, the work of challenging inequitable practices can be draining for equity advocates. It requires them to raise uncomfortable questions about structural racism that may make their colleagues anxious. What this study adds is the perspective of the untrained committee colleagues who worked with the EAs. Psychologists have long known that implicit biases are deeply rooted and are either unaffected or exacerbated by short-term trainings. Yet, higher education has widely embraced implicit bias training for faculty and staff members. In our study, only EAs received training, and they did so by choice and over several weeks. EAs concentrated their efforts on reforming search processes, not committee members’ mindsets. Aside from some initial suspicion, untrained committee members seemed genuinely grateful for the contributions of the EAs. They viewed EAs as helpful guardrails, keeping them centered on the path of their good intentions and steering them back on course if they veered. We found no evidence of resentment or backlash from the untrained committee members. To the contrary, they independently identified ways they could apply the lessons of bias reduction in other parts of their professional roles. Our study provides evidence for how to engage all faculty and staff members in sustainable equity-minded efforts.

Awareness of bias helps promote equity but is not enough on its own to eliminate all unfair practices. Structural barriers like limited resources to support active recruitment and pressures to plug gaps in teaching needs prevent search committees from attracting and objectively evaluating the widest range of available talent. Still, the experience at the Institute suggests that adding trained EAs to search committees may be an effective and feasible intervention for many institutions of higher education. Recognizing that dismantling the damaging effects of implicit bias will require systemic interventions, some universities have begun to experiment with adding family advocates to the search process to discuss work-life integration with candidates (Smith et al., 2015). Adding trained advocates to search committees incorporates insights from psychology to invite everyone to participate in the collective work of ensuring equity in higher education.

Biographies

Peter S. Cahn

is associate provost for academic affairs at MGH Institute of Health Professions. As a cultural anthropologist, he has conducted ethnographic fieldwork in the United States and Latin America. His research interests include health professions education, interprofessional practice, and the culture of higher education.

Clara M. Gona

is associate professor and track co-coordinator for the family nurse practitioner specialty in the School of Nursing at MGH Institute of Health Professions. She received her Ph.D. in nursing from Boston College. Her community-based research focuses on African immigrants and their risks for cardiovascular disease.

Keshrie Naidoo

is assistant professor and coordinator of the clinical residency in orthopaedic physical therapy at MGH Institute of Health Professions. She received her Ed.D. from Johns Hopkins University with a specialty in entrepreneurial leadership in education. Her publications have explored the experiences of culturally and linguistically diverse learners in graduate school.

Kimberly A. Truong

serves as the inaugural chief equity officer at MGH Institute of Health Professions. She received a Ph.D. in higher education at University of Pennsylvania. She has conducted research on access and equity issues in higher education, the experiences of doctoral students of color with racism, and higher education policy.

Appendix

Semi-Structured Interview Protocol for Non-Equity Advocates

Before the Search

What has been your experience of faculty searches before the one you participated in this year?

Have you ever received training on how to conduct a faculty search?

Before the current search, how aware were you of biases in the faculty search process?

During the Search

For those who have participated in a search committee without an EA, what difference, if any, did having a person in that role make?

Give an example of how the participation of an EA affected a committee decision.

What steps did you take as a committee to recruit candidates from underrepresented groups?

After the Search

What could be improved about the search committee process?

How do you feel about the outcome of the search?

Is there anything you learned about bias during the search that you’ll apply to other parts of your professional role?

Semi-Structured Interview Protocol for Equity Advocates

Before the Search

What has been your experience of faculty searches before the one you participated in this year?

What were your primary takeaways from the equity advocate training?

What strategies did you employ to become integrated into the search committee?

During the Search

Did you see examples of bias in search practices or processes? If so, what were they?

How were you able to call attention to bias? What was the result?

What, if anything, did you draw on from your equity advocate training to perform your role? What additional preparation would have been helpful?

What steps did you take as a committee to recruit candidates from underrepresented groups?

After the Search

What could be improved about the search committee process?

How do you feel about the outcome of the search?

Is there anything you learned about bias during the search that you’ll apply to other parts of your professional role?

What advice would you give to other EAs?

Authors’ Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. All authors contributed to the data collection and analysis. All authors contributed to writing the first draft of the manuscript, and the corresponding author revised it for consistency. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Data Availability

The human resource data and focus group transcripts are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

A code list for the qualitative data is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Approval

MassGeneral Brigham IRB Protocol #2019P003153.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Banaji, M. R. & Greenwald, A. G. (2013). Blindspot: Hidden biases of good people. Delacorte Press.

- Bensimon EM. Reclaiming racial justice in equity. Change The Magazine of Higher Learning. 2018;50(3-4):95–98. doi: 10.1080/00091383.2018.1509623. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla N. Strategies to improve equity in faculty hiring. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2019;30(22):2744–2749. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E19-08-0476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilimoria D, Buch KK. The search is on: Engendering faculty diversity through more effective search and recruitment. Change The Magazine of Higher Learning. 2010;42(4):27–32. doi: 10.1080/00091383.2010.489022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burroughs EA. Reducing bias in faculty searches. Notices of the American Mathematical Society. 2017;64(11):1304–1307. doi: 10.1090/noti1600. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davey BTL, Johnson KF, Webb L, White E. Recruitment inclusive champions: Supporting university diversity and inclusion goals. The Journal of Faculty Development. 2021;35(2):50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbin F, Kalev A. Why diversity programs fail. Harvard Business Review. 2016;94(7):14. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbin F, Kalev A. Why doesn’t diversity training work? The challenge for industry and academia. Anthropology Now. 2018;10(2):48–55. doi: 10.1080/19428200.2018.1493182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dover TL, Major B, Kaiser CR. Members of high-status groups are threatened by pro-diversity organizational messages. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2016;62:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2015.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL, Pearson AR. Aversive racism and contemporary bias. In: Sibley CG, Barlow FK, editors. The Cambridge handbook of the psychology of prejudice. Cambridge University Press; 2016. pp. 267–294. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott V. Thinking about the coding process in qualitative data analysis. The Qualitative Report. 2018;23(11):2850–2861. [Google Scholar]

- Forscher PS, Lai CK, Axt JR, Ebersole CR, Herman M, Devine PG, Nosek BA. A meta-analysis of procedures to change implicit measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2019;117(3):522–559. doi: 10.1037/pspa0000160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser GJ, Hunt DE. Faculty diversity and search committee training: Learning from a critical incident. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education. 2011;4(3):185–198. doi: 10.1037/a0022248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs KD, Basson J, Xierali IM, Broniatowski DA. Decoupling of the minority PhD talent pool and assistant professor hiring in medical school basic science departments in the US. eLife. 2016;5(e21393):1–20. doi: 10.7554/eLife.21393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KA. Institutional barriers, strategies, and benefits to increasing the representation of women and men of color in the professoriate. In: Perna LW, editor. Higher education: Handbook of theory and research. Springer; 2020. pp. 277–349. [Google Scholar]

- Guba EG. Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. Educational Technology Research and Development. 1981;29:75–91. doi: 10.1007/BF02766777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Justice AC. Leaky pipes, Faustian dilemmas, and a room of one’s own: Can we build a more flexible pipeline to academic success? Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;151(11):818–819. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-151-11-200912010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai CK, Marini M, Lehr SA, Cerruti C, Shin JEL, Joy-Gaba JA, Ho AK, Teachman BA, Wojcik SP, Koleva SP, Frazier RS, Heiphetz L, Chen EE, Turner RN, Haidt J, Kesebir S, Hawkins CB, Schaefer HS, Rubishi S, Nosek BA. Reducing implicit racial preferences: I. A comparative investigation of 17 interventions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2014;143(4):1765. doi: 10.1037/a0036260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liera R. Equity advocates using equity-mindedness to interrupt faculty hiring’s racial structure. Teachers College Record. 2020;122(9):1–42. doi: 10.1177/016146812012200910. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liera R. Moving beyond a culture of niceness in faculty hiring to advance racial equity. American Educational Research Journal. 2020;57(5):1954–1994. doi: 10.3102/0002831219888624. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liera R, Ching C. Reconceptualizing “merit” and “fit”: An equity-minded approach to hiring. In: Kezar A, Posselt J, editors. Administration for social justice and equity in higher education: Critical perspectives for leadership and decision-making. Routledge; 2019. pp. 111–131. [Google Scholar]

- Lochmiller, C. R., & Lester, J. N. (2017). An introduction to educational research: Connecting methods to practice. Sage.

- McMurtrie, B. (2016, September 16). How to do a better job of searching for diversity. Chronicle of Higher Education, A20–A25.

- McNair TB, Bensimon EM, Malcom-Piqueux L. From equity talk to equity walk: Expanding practitioner knowledge for racial justice in higher education. Jossey-Bass. 2020 doi: 10.1002/9781119428725. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monteith MJ, Sherman JW, Devine PG. Suppression as a stereotype control strategy. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 1998;2(1):63–82. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson RS. Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology. 1998;2(2):175–220. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Meara KA, Culpepper D, Templeton LL. Nudging toward diversity: Applying behavioral design to faculty hiring. Review of Educational Research. 2020;90(3):311–348. doi: 10.3102/0034654320914742. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Onwuegbuzie AJ, Dickinson WB, Leech NL, Zoran AG. A qualitative framework for collecting and analyzing data in focus group research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2009;8(3):1–21. doi: 10.1177/160940690900800301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pritlove C, Juando-Prats C, Ala-leppilampi K, Parsons JA. The good, the bad, and the ugly of implicit bias. The Lancet. 2019;393(10171):502–504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32267-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JA, Brock S, Rudisill ME. Recognizing the impact of bias in faculty recruitment, retention, and advancement processes. Kinesiology Review. 2019;8(4):291–295. doi: 10.1123/kr.2019-0043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sekaquaptewa D, Takahashi K, Malley J, Herzog K, Bliss S. An evidence-based faculty recruitment workshop influences departmental hiring practice perceptions among university faculty. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion. 2019;38(2):188–210. doi: 10.1108/EDI-11-2018-0215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sensoy, O., & DiAngelo, R. (2017). “We are all for diversity, but . . .”: How faculty hiring committees reproduce whiteness and practical suggestions for how they can change. Harvard Educational Review, 87(4), 557–581. 10.17763/1943-5045-87.4.557

- Shea CM, Malone MFFT, Young JR, Graham KJ. Interactive theater: An effective tool to reduce gender bias in faculty searches. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion. 2019;38(2):178–187. doi: 10.1108/EDI-09-2017-0187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JL, Handley IM, Zale AV, Rushing S, Potvin MA. Now hiring! Empirically testing a three-step intervention to increase faculty gender diversity in STEM. BioScience. 2015;65(11):1084–1087. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biv138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley JM, Capers CF, Berlin LE. Changing the face of nursing faculty: Minority faculty recruitment and retention. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2007;23(5):253–261. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Torino GC, Capodilupo CM, Rivera DP, Lin AI. How white faculty perceive and react to difficult dialogues on race: Implications for education and training. The Counseling Psychologist. 2009;37(8):1090–1115. doi: 10.1177/0011000009340443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor O, Burgan Apprey C, Hill G, McGrann L, Wang J. Diversifying the faculty. Peer Review. 2010;12(3):59. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, K. A. & Martinez, K. (2021). From DEI to JEDI. Diverse: Issues in Higher Education. https://diverseeducation.com/article/211514/.

- Tuitt, F. A., Danowitz, S. M. A., & Turner, C. S. V. (2007). Signals and strategies in hiring faculty of color. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research, 22 (pp. 497–536). Springer. 10.1177/000271622310700120

- White-Lewis DK. The facade of fit in faculty search processes. Journal of Higher Education. 2020;91(6):833–857. doi: 10.1080/00221546.2020.1775058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White-Lewis DK. Before the ad: How departments generate hiring priorities that support or avert faculty diversity. Teachers College Record. 2021;123(1):1–36. doi: 10.1177/016146812112300109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MA, DePass AL, Bean AJ. Institutional interventions that remove barriers to recruit and retain diverse biomedical PhD students. CBE Life Sciences Education. 2018;17(2):1–14. doi: 10.1187/cbe.17-09-0210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The human resource data and focus group transcripts are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

A code list for the qualitative data is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.