Abstract

Hip osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative joint disease that results in substantial morbidity. The disease may be preventable in some instances by reducing risk factors associated with the disease. We undertook a study to determine whether being overweight or obese, a health risk that applies to younger and older age groups, is commonly associated with hip joint OA. The body mass indices (BMIs) of 1021 males and females ranging in age from 23 to 94 years and requiring surgery for end-stage hip joint OA were analyzed to find the prevalence of high body weights at the time of surgery. Being overweight was defined as having a BMI of 25–29.9 kg/m2 and being obese as having a BMI >30 kg/m2. BMIs indicative of overweight were recorded for 68% of the patients surveyed. Of 35 patients aged 30–39 years, 53.3% had BMIs >25, with a mean of 28.8, which nearly reaches the lower limit defined for obesity. On average, patients who had had previous surgery and complications warranting reimplantation of new surgical devices had BMIs in the obese range. Our findings suggest that a high percentage of patients with end-stage hip OA are overweight, including younger adults and those with symptoms of 3–6 months' duration. Moreover, patients whose BMIs are in the obese range may be at increased risk for removal and reimplantation of their prosthesis.

Keywords: arthroplasty surgery, body mass index, hip joint, osteoarthritis

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) of the hip is a frequent source of functional disability and pain in people over the age of 55 years. While the disease is generally assumed to be age related, there is evidence that health risk behaviors that might be potentially modifiable are involved in its development [1,2]. Despite some evidence linking overweight and hip OA [3,4,5,6], this finding is equivocal and has previously been documented mainly in small studies of relatively young people, usually in the absence of radiographic evidence [6,7].

The specific objective of this study was to examine whether excess body weight, a health risk that is potentially amenable to intervention, might be associated with hip OA. We hypothesized that because of a history of sedentarity, pain and/or a high prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidi-ties, patients diagnosed as having clinical and radiographic hip OA would tend to be overweight or obese, rather than underweight or of normal weight. We further expected that if weight is implicated in producing damage at the hip joint, the prevalence of high body mass indices (BMIs) might be higher in patients with hip OA than in the general population. Finally, because infection or prosthetic loosening after hip replacement might be weight-related, we sought to explore whether individuals requiring either prosthetic removal or reimplantation surgery are overweight or obese.

Methods

The presurgical BMIs of 1021 males and females, ranging in age from 23 to 94 years and who had been diagnosed clinically and radiographically as having moderate to severe end-stage unilateral or bilateral hip OA, were calculated from the appropriate height and weight data found recorded in their complete medical records. The severity of the patients' condition was determined by their Kellgren grades on radiographs and by the Hospital for Special Surgery Hip Scoring System, which includes an assessment of pain, walking status, muscle power and overall function, using a 10-point scale for each parameter. Patients with a history of rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, Lyme disease, septic arthritis and traumatic arthritis were excluded.

These data, which were available for the majority of patients undergoing arthroplasty of one or both hip joints between January 1 and October 31, 2000, were collected systematically, along with pertinent demographic and clinical data by checking the hospital admissions at least three times a week. Excluded were patients for whom all data were not available. The single hospital population sampled was at the Hospital for Special Surgery, a world-renowned orthopedic hospital treating difficult cases of OA as well as standard cases of the disease from all states of North America and all boroughs of New York city. The BMI data were categorized according to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines of 1988–1994 [8] and entered systematically onto a spreadsheet for purposes of primary analysis. Patients were classified as underweight if their BMI was <18.5 kg/m2, of normal weight if it was 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, overweight if it was 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 and obese if it was ≥ 30 kg/m2. Additional BMI data required for comparison purposes were obtained from currently available population-based estimates of BMIs in the American adult population [8,9,10] and from 110 age-matched patients of both genders without symptomatic hip osteoarthritis who were hospitalized concurrently.

After the data had been coded and categorized according to gender, laterality, and surgical-procedure requirements, the BMI data were stratified and analyzed with respect to one of eight age groups: 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, 80–89, 90–95 years. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Version 10 software.

Results

Patient characteristics

Of the 1021 subjects studied, 586 were females and 435 were males, with an average age of 66.09 ± 12.70 years. Ninety-three percent were white and 7% were either black, Hispanic or of Middle Eastern ancestry. Over 90% had evidence of a pre-existing medical condition, and the 55 cases requiring bilateral hip surgery were younger on average, with a mean age of 54.24 ± 13.27 years than those undergoing other procedures (P ≤ 0.001). The patients' age at symptomatic onset of their disease ranged from 3 months to 25 years. Their overall impairment level was indicative of a cohort with mild or moderate functional impairments, requiring use of a walking aid in 25% of the cases. There were none that could be classified as having normal physical function without impairment. There were also none that could be defined as having serious impairment, such as being bedridden or aphasic.

BMI distributions

BMIs indicative of overweight or obesity were recorded for almost 70% of all patients in the cases surveyed, while only 1% were classified as underweight. In contrast to age-adjusted population data for adults aged 20–74, of whom 27% are considered obese [10], approximately 30% of the patient sample we studied were obese. The percentage of patients classified as overweight was also higher than the current prevalence of overweight in the adult population, approximately 34% [10].

The patients with hip OA in our study also had higher BMIs than those of 55 hospitalized patients with hip fracture, 25 patients without any symptomatic hip problem who had an average BMI of 23, 25 patients without any symptomatic hip problem who had an average BMI of 24, or 30 patients with rheumatoid arthritis who had a mean BMI of 26.4.

Age associations

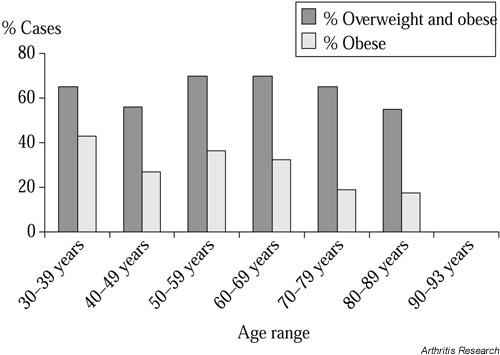

BMIs indicated that each age group was on average overweight or obese, except for age groups 20–29 and 90–95 years, where BMIs were 24.0 ± 2.7 and 23.0 ± 1.9, respectively. As shown in Fig. 1, the highest percentage of overweight or obese patients was found in the age ranges 50–59 and 60–69 years, the average age at which hip OA is generally expected to occur in any population. However, although individuals in these age groups were also categorized as being obese more often than older patients or those 40–49 years of age, the 30–39-year age group contained the highest percentage of obese patients of all (P ≤ 0.001), and their average BMI (28.2 ± 7.3 kg/m2) was very close to the definition of obesity.

Figure 1.

Percentage of patients with hip osteoarthritis who were overweight or obese, according to age (N = 1021).

Gender associations

Males had higher mean BMIs than females in all age groups except 30–39 years. Analysis according to weight categories showed that more males than females were overweight or obese in all categories except the morbidly obese (BMI >40 kg/m2), where there were 20% more females than males. Among all the patients with hip OA, a smaller percentage of males than of females were categorized as having 'normal' BMIs or as being underweight.

Comparative data

Similar BMI values were found for patients undergoing unilateral and bilateral hip replacement and revision surgery. However, the patients with left-sided lesions tended to be heavier than those with right-sided lesions. As Table 1 shows, those who had comorbidities, including cardiac disease, hypertension, and diabetes, were heavier than those with no comorbid disease history.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample of 1021 patients with osteoarthritis of the hip joint who were hospitalized for total hip replacement surgery or related procedures between January 1 and October 31, 2000

| Characteristic | Subgroup | Value |

| Age (years) | Whole group | 66.09 ± 12.70 |

| Males | 62.83 ± 12.55** | |

| Females | 67.38 ± 13.00 | |

| Gender (no.) | Males | 435 |

| Females | 586 | |

| Side affected (no.) | Left | 451 |

| Right | 507 | |

| Procedure (no.) | Unilateral hip replacement | 781 |

| Bilateral hip replacement | 55 | |

| Reimplantation of prosthesis | 16 | |

| Removal of prosthesis | 27 | |

| Revision of prior prosthetic surgery | 134 | |

| Debridement | 3 | |

| Relocation of prosthesis | 4 | |

| Second removal | 1 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | Whole group | 27.63 ± 5.78 |

| Left side affected | 28.02 ± 6.25* | |

| Right side affected | 27.28 ± 5.28 | |

| Males | 28.77 ± 5.16** | |

| Females | 26.70 ± 5.93 | |

| Healthy group | 26.98 ± 4.48*** | |

| Comorbid group | 27.75 ± 5.92 | |

| Those having reimplantations | 31.21 ± 5.65 | |

| Health status (%) | Free of other disease | 10 |

| With comorbid disease(s) | 90 |

Values are shown as mean ± 1 SD unless otherwise indicated. BMI = body mass index. *P = 0.049, **P = 0.000, ***P = 0.007.

Twenty-seven patients with unilateral infected prostheses that required prosthetic removal, plus an additional 16 patients (15 with unilateral disease) who were undergoing reimplantation surgery because of uncontrolled infection, had higher BMIs than those of the other hospitalized patients with hip OA (P ≤ 0.008). One of the removed pros-theses was a replacement following a previous removal postinfection in 1999, in a 54-year-old white man with a BMI of 40 and a history of diabetes and atrial fibrillation.

Patients with complications

Of the subgroup of patients who required either removal or reimplantation of a prosthesis, males were rehospital-ized at twice the rate of females and as a group were heavier on average, with a mean BMI of 31.3 ± 7.8 kg/m2, versus 28.5 ± 5.3 kg/m2 for the females. The males were also younger (mean age 58.9 ± 12.35 years) than the females requiring the same procedure (mean age 71.75 ± 7.9 years). At ages 30–39 years, an age range not implicitly associated with the presence of degenerative disease of the hip, 34 patients had evidence of a prior comorbid disease history. Of these, four required surgical revision and one required reimplantation surgery.

Regression analysis showed that of age, side, type of surgical procedure (unilateral or bilateral joint replacement, revision, debridement, relocation or reimplantation) and gender, the only significant predictor of BMI was surgery type (P < 0.035).

Discussion

Our most important finding was that at least two-thirds of the patients in our sample were overweight at the time of their surgery. This figure is higher than that recorded among men ages 20–39 years in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III sample, in which 43% had a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or higher [2]. The high BMIs recorded for those in the 30–39 year age range (mean for females 28.3 kg/m2 and for males, 27.9 kg/m2) were very similar to those deemed by Heliovaara et al. [11] and Roach et al. [12] to increase the risk of developing hip OA.

Furthermore, the high BMIs, which are rough indicators of fatness, were observed to a similar extent with respect to both unilateral and bilateral cases of hip OA. This is noteworthy because according to the NHANES findings of Tepper and Hochberg [13], and a related study by Nevitt et al. [9], obesity is associated more strongly with bilateral than with unilateral hip OA [14]. Our findings are also interesting in light of the case–control study by Vingård [15] of 239 men with BMIs greater than the mean + 1 SD for the general population; that study did show an increased risk of developing severe hip OA in these individuals than in individuals with a BMI less than the mean + 1 SD. Those slightly obese at 40 years of age had a relative risk of 2.5 for later surgery of the hip. Although Hartz et al. [7] found OA of the hips was significantly associated with obesity only in white females and nonwhite males, 38% of the our study group comprised white males, a group noted by Kellgren and Lawrence to be at risk for OA of the hips [16]. Overall, the percentage of patients with hip OA who had BMIs in the overweight or obese range was higher than those BMIs reported for American adults in general [10]. In our study, almost twice as many young adults 30–39 years of age with hip OA (an age when significant hip OA is relatively uncommon) were obese or overweight relative to national standards [8,9,10]. While these population standards are subject to error and may not be representative of our patients because of sociodemographic and other factors, we observed that nonosteoarthritic adults of similar ages had lower BMIs on average than those with OA of the hip in the context of the same hospital site and study time period.

While having hip OA could lead to obesity, and while overweight and hip OA may not be related and hip OA may not occur in all populations to the same extent [14,17], it is possible that cumulative exposure to excessive body mass may increase the risk of subsequently developing hip OA [1,2] and the worsening of the disease [11,12,15,18]. This could occur through either metabolic or mechanical mechanisms, or both, and these mechanisms could prevail to differing degrees in susceptible males and females. Although, with rare exceptions, no independent relation has been found to exist between metabolic correlates of obesity and the presence of knee OA [7,19], the same relation may not apply to the hip joint [20]. It has also been shown recently that those who have high BMIs are likely to have decreased hip joint rotation and lower strength capacity as a consequence of obesity [21,22], and this may detrimentally affect the loading patterns at the hip joint by fostering the repetitive application of greater axial loads than the hip joint can accommodate [19,23].

Our study design and data analyses do not permit us to discern what the initiating factor causing the patients' hip OA was, or whether having hip OA may lead to pain and a sedentary lifestyle. Moreover, we cannot determine whether a subsequently increased BMI is more important than other factors in increasing the risk of hip OA. However, studies of the effects of body mass on avian degenerative joint disease, which shares common pathologies with human degenerative disease, have clearly shown that OA can be mediated by body mass [24]. That the majority of patients who required prosthetic reimplantation had high BMIs may indicate an association between being overweight and a poor postsurgical prognosis [25]. This observation is further supported by the study of Stickles et al. [26], who observed an association between BMI and problems climbing stairs 1 year after total joint arthroplasty. There is also a weak association between pain in the hip and BMI [27], and evidence that body weight and BMI are significant predictors of the onset of OA of the hip [5]. That prosthetic removals were warranted for a greater proportion of males than females in our study, even though males constituted a smaller proportion of the study sample as a whole (P < 0.01), may imply the existence of different pathogenic processes for males and females. The finding that more obese males under the age of 60 sustained postoperative infections than females suggests that obese males with hip OA under the age of 60 years may be especially vulnerable to postoperative infection and may therefore have a poor prognosis.

Because we did not obtain serial measurements in this study, the high BMIs observed for a large percentage of the hip arthritis patients cannot be deemed causative of the disease process. Conversely, we have no evidence that hip OA led to the presence of high BMIs in our study sample. Yet the possible influence of high BMIs in mediating postoperative hip infections and further hip OA disability cannot be ignored. Our data suggest that we should not exclude the possibility that the proclivity to be inactive, together with high body masses that produce increased joint loading, may have resulted in the premature hospitalization of the 30–39-year-olds in this sample. Approximately 95% of the cases we studied had medical evidence of long-standing cardiovascular insufficiencies and other comorbidities such as hypertension.

Finally, although frame size, muscularity, fat distribution and the changes of aging may all be reasons for persons being classified as having a high BMI, as might the factor of height [28], the implications of our data for preventing hip joint disease should not be overlooked. Although the measure of BMI is not an ideal measure and does not reflect the distribution of obesity at all adequately, it remains the preferred measure of fatness for epidemiological studies [28]. Our conclusion that body mass may influence the etiopathogenesis of hip OA is also supported by the work of others [2,5,24,29,30,31].

Although not without limitations, our data provide additional support for the view that symptomatic unilateral and bilateral hip OA is associated with an increased BMI, especially between the ages of 30 and 59 years. Patients with post-prosthesis complications may also have increased BMIs. This suggests that interventions to prevent overweight early in adulthood may mitigate the magnitude and prevalence of hip OA and its related disability. Longitudinal analyses of larger samples to confirm the present findings and to test the above hypothesis are warranted.

Abbreviations

BMI = body mass index; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; NHANES = National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; OA = osteoarthritis; SD = standard deviation.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Dr Marks is supported, in part, by a SOPHE/CDC Student Fellowship in Unintentional Injury Prevention.

References

- Felson DT. Preventing knee and hip osteoarthritis. Bull Rheum Dis. 1998;47:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelber AC, Hochberg MC, Mead LA, Wang NY, Wigley FM, Klag MJ. Body mass index in young men and the risk of subsequent knee and hip osteoarthritis. Am J Med. 1999;107:542–548. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00292-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felson DT, Chaisson CE. Understanding the relationship between body weight and osteoarthritis. Ballière's Clin Rheumatol. 1997;11:671–681. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3579(97)80003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoadhiar L, McCowen KC, Blackburn GL. Obesity and its comorbid conditions. Clin Cornerstone. 1999;2:17–31. doi: 10.1016/s1098-3597(99)90002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveria SA, Felson DT, Cirillo PA, Reed JI, Walker AM. Body weight, body mass index, and incident symptomatic osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Epidemiology. 1999;10:161–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevitt M, Lane N. Body weight and osteoarthritis. Am J Med. 1999;107:632–633. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00297-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartz AJ, Fischer ME, Bril G, Kelber S, Rupley D, Jr, Oken B, Rimm AA. The association of obesity with joint pain and osteoarthritis in the Hanes data. J Chronic Dis. 1986;39:311–319. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(86)90053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994 Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics, Division of Data Services; 2001.

- Nevitt MC, Lane NE, Scott JC, Genant HK, Hochberg MC, Cummings SR, and the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group Relationship of hip osteoarthritis to obesity and bone mineral density in older American woman: preliminary results from the study of osteoporotic fractures. Acta Orthop Scandinav. 1993;64(suppl):2–5. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among adults: United States, 1999 Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, September 13, 2001. http:www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/pubs/pubd/hestats/obese/obse99t2.htm

- Heliovaara M, Makela M, Impivaara O, Knekt P, Aromaa A, Sievers K. Association of overweight, trauma, and workload with coxarthrosis: a health survey of 7217 persons. Acta Orthop Scandinav. 1993;64:513–518. doi: 10.3109/17453679308993681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach KE, Persky V, Miles T, Budiman-Mak E. Biomechanical aspects of occupation and osteoarthritis of the hip: a case–control study. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:2334–2340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepper S, Hochberg MC. Factors associated with hip osteoarthritis: Data from the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES-1). Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137:1081–1088. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturmer T, Gunther KP, Brenner H. Obesity, overweight and patterns of osteoarthritis: the Ulm osteoarthritis study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:307–313. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vingård E. Overweight predisposes to coxarthrosis. Body-mass index studied in 239 males with hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Scandinav. 1991;62:106–109. doi: 10.3109/17453679108999233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Osteoarthrosis and disk degeneration in an urban population. Ann Rheum Dis. 1958;17:388–396. doi: 10.1136/ard.17.4.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura N, Sasaki S, Iwasaki K, Danjoh S, Kinoshita H, Yasuda T, Tamaki T, Hashimoto T, Kellingray S, Croft P, Coggon D, Cooper C. Occupational lifting is associated with hip osteoarthritis: a Japanese case–control study. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:434–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okma-Keulen , Hopman-Rock M. The onset of generalized osteoarthritis in older women: a qualitative approach. Arthritis Care Res. 2001;45:183–190. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200104)45:2<183::AID-ANR172>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma L, Lou C, Cahue S, Dunlop DD. The mechanisms of the effect of obesity in knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:568–575. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200003)43:3<568::AID-ANR13>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspden RM, Scheven BAA, Hutchison JD. Osteoarthritis as a systemic disorder including stromal cell differentiation and lipid metabolism. Lancet. 2001;357:1118–1120. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04264-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettunen JA, Kujala UM, Raty H, Videman T, Sarna S, Impivaara O, Koskinene S. Factors associated with hip joint rotation in former athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2000;34:44–48. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.34.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulens M, Vansant G, Lysens R, Claessens AL, Brumagne S. Study of differences in peripheral muscle strength of lean versus obese women: an allometric approach. Int J Obesity. 2001;25:676–681. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed IY, Davis BL. Obesity and osteoarthritis of the knee: Hypotheses concerning the relationship between ground reaction forces and quadriceps fatigue in long-duration walking. Med Hypotheses. 2000;54:182–185. doi: 10.1054/mehy.1999.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson-MacKenzie JM, Hulmes DJS, Thorp BH. Effects of body mass and genotype on avian degenerative joint disease pathology and articular cartilage proteoglycan distribution. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1998;16:403–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young NL, Cheah D, Waddell JP, Wright JG. Patient characteristics that affect the outcome of total hip arthroplasty: a review. Can J Surg. 1998;41:188–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickles B, Phillips L, Brox WT, Owens B, Lanzer WL. Defining the relationship between obesity and total joint arthroplasty. Obes Res. 2001;9:219–223. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Ross PD, Lydeck E, Wasnich RD. Factors associated with joint pain among postmenopausal women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997;21:349–354. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welborn TA, Knuiman MW, Vu HTV. Body mass index and alternative indices of obesity in relation to height, triceps skinfold and subsequent mortality: the Busselton Health Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:108–115. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus JF, d'Amrosia RD, Smith EG, Van Meter J, Borhani NO, Franti CE, Libscomb PR. An epidemiological study of severe osteoarthritis. Orthopedics. 1978;1:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen O, Vingård E, Koster M, Alfredsson L. Etiologic fractions for physical work load, sports and overweight in the occurrence of coxarthrosis. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1994;20:184–188. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vingård E, Alfredsson L, Malchau H. Lifestyle factors and hip arthrosis. A case referent study of body mass index, smoking and hormone therapy in 503 Swedish women. Acta Orthop Scand. 1997;68:216–220. doi: 10.3109/17453679708996687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]