Abstract

Aberrant morphological changes in lumbar multifidus muscle (LMM) are prevalent among patients with low back pain (LBP). Motor control exercise (MCE) aims to improve the activation and coordination of deep trunk muscles (eg, LMM), which may restore normal LMM morphology and reduce LBP. However, its effects on LMM morphology have not been summarized. This review aimed to summarize evidence regarding the (1) effectiveness of MCE in altering LMM morphometry and decreasing LBP; and (2) relations between post-MCE changes in LMM morphometry and LBP/LBP-related disability. Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, MEDLINE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, the Physiotherapy Evidence Database, EMBASE and SPORTDiscus were searched from inception to 30 September 2020 to identify relevant randomized controlled trials. Two reviewers independently screened articles, extracted data, and evaluated risk of bias and quality of evidence. Four hundred and fifty-one participants across 9 trials were included in the review. Very low-quality evidence supported that 36 sessions of MCE were better than general physiotherapy in causing minimal detectable increases in LMM cross-sectional areas of patients with chronic LBP. Very low- to low-quality evidence suggested that MCE was similar to other interventions in increasing resting LMM thickness in patients with chronic LBP. Low-quality evidence substantiated that MCE was significantly better than McKenzie exercise or analgesics in increasing contracted LMM thickness in patients with chronic LBP. Low-quality evidence corroborated that MCE was not significantly better than other exercises in treating people with acute/chronic LBP. Low-quality evidence suggested no relation between post-MCE changes in LMM morphometry and LBP/LBP-related disability. Collectively, while MCE may increase LMM dimensions in patients with chronic LBP, such changes may be unrelated to clinical outcomes. This raises the question regarding the role of LMM in LBP development/progression.

Keywords: imaging, LMM, LBP, morphometry

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP), defined as pain or discomfort between the twelfth ribs and buttocks,1,2 is the leading cause of disability worldwide.3 It affects up to 84% of people at least once in their lifetime. The prevalence of LBP is anticipated to increase with an aging global population.4 Since LBP can lead to tremendous medical burdens and work disability, the overall cost of LBP is expected to increase over time.4 Although LBP is ubiquitous, approximately 85% of LBP cases have unclear etiology.5 Biomechanical research suggests that the occurrence/maintenance of LBP may be related to the suboptimal motor control of deep trunk muscles.6 Specifically, lumbar multifidus muscle (LMM) is a major paraspinal muscle that provides intersegmental control of the spine7–9 and withstands the compressive loading of the lumbar spine.10 Therefore, structural/functional deficits of LMM may be related to the onset or maintenance of chronic LBP (CLBP).

Compared to asymptomatic individuals, some patients with acute or chronic LBP demonstrate morphometric and/or functional changes in LMM (eg, reduced cross-sectional area (CSA),11–15 increased intramuscular fatty infiltration,14,16–18 decreased resting thickness,19 and percentage thickness changes during maximum voluntary isometric contraction19 or contralateral arm lift).20,21 However, no significant relation between CSA/fatty infiltration of LMM and LBP has also been reported.22 Although LMM atrophy may be specific to the location and the side of symptoms,23 prolonged immobilization may also result in general LMM atrophy.10 Given the close association between LMM and LBP, one rehabilitation approach is to improve the function and morphology of LMM. Of various physiotherapy interventions, motor control exercise (MCE) is thought to be able to restore LMM morphology and function in patients with LBP.2,24 Multiple studies have investigated the effectiveness of MCE in restoring normal LMM morphometry25,26 or decreasing LBP among patients with CLBP.27–30 Some found that MCE increased LMM sizes in these patients2,30,31 Although a recent Cochrane review found low- to moderate-quality evidence to support MCE in inducing clinically meaningful pain reduction in patients with CLBP as compared to different kinds of controls including sham intervention and education,32 no review has summarized the effectiveness of MCE in concomitantly restoring LMM morphology and reducing LBP. Further, temporal relations between post-MCE changes in LMM morphology and changes in pain intensity/LBP-related disability among patients with LBP have not been summarized. Therefore, this systematic review aimed to summarize the evidence regarding (1) the effectiveness of MCE in restoring normal LMM morphometry and decreasing LBP; and (2) whether the post-treatment changes in morphology were associated with changes in pain and/or function of patients with LBP.

Methods

Identification and Selection

This review conforms to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines and is registered with PROSPERO (CRD42019120978).33 A systematic search was conducted in CINAHL, MEDLINE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro), EMBASE and SPORTDiscus from inception to 30 September 2020. Non-English publications were excluded. The search keywords and Medical Subject Headings included were related to LBP, lumbar multifidus, physiotherapy, or rehabilitation (Appendix 1). Studies were included if they: (1) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs); (2) involved people with LBP regardless of chronicity; and (3) compared effects of MCE with another intervention/control groups(s) on at least one morphological/morphometric change of LMM (eg, CSA, resting/contracted thickness, percent thickness change during contraction, intramuscular fatty infiltration) (see Appendix 2 for details). Studies involving surgical interventions or cross-sectional comparisons between asymptomatic and symptomatic individuals, review articles, conference proceedings, theses, animal studies and grey literature were excluded. The reference lists of systematic reviews related to LMM morphology/morphometry were reviewed to identify relevant primary studies. The reference lists of the included studies were tracked backward, while forward citation tracing was performed using Web of Science. The corresponding authors of the included studies were contacted to identify additional relevant publications.

Two reviewers (SMP and SBB) independently screened the titles and abstracts based on the selection criteria. Potential full-text articles were retrieved and reviewed. Disagreements in the study inclusion at each stage were resolved by discussion. Any unresolved disagreements were decided by a third reviewer (AW). The inter-rater agreement at each screening stage was analyzed by Kappa coefficients (κ). The agreement was interpreted as none to slight (κ=0.01–0.20), fair (κ=0.21–0.40), moderate (κ=0.41–0.60), good agreement (κ=0.61–0.80), or almost perfect (κ=0.81–1.00).34

Data Extraction

The two reviewers independently extracted authors’ names, year of publication, case definition, sample size, patients’ characteristics, intervention details, outcome measures, measurement methods, attrition rate, and pre- and post-treatment results using a standardized extraction form. The primary outcome measures included LMM morphometry (eg, resting, and contracted LMM thickness, percent thickness change during contraction, volume, CSA, and intramuscular fatty infiltration, etc.) and pain. The LMM morphometric data (eg, CSA, volume, resting thickness, contracted thickness, percent thickness changes) at each lumbar level on both sides were extracted from each included study, whenever possible. Percent thickness change was calculated from [(thickness contracted – thickness rest)/thickness rest x 100].35 Greater percent LMM thickness change during contraction as measured by ultrasonography was thought to be an indirect measure of LMM contraction.36,37 The LMM CSA was commonly used to estimate the muscle atrophy/weakness.22 Increased muscle CSA signified muscle hypertrophy.38,39 Secondary outcome measures included correlations between changes in LMM morphology and LBP intensity/LBP-related disability.

Risk of Bias Assessment

The two reviewers (SMP and SBB) independently assessed the Risk of Bias (RoB) using the Cochrane collaboration RoB Tool (RoB 2.0).40 Any disagreements regarding the scores were resolved by the third reviewer (AW). Each item was scored as low, some concern, or high risk of bias according to the Cochrane handbook descriptions.

The GRADE Approach

The two authors (SMP and SBB) independently assessed the quality of evidence of the primary outcomes using the GRADE as per GRADE handbook of grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. The assessment was based on the study design, risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and other considerations.41 The quality of evidence was rated at four levels: high, moderate, low, and very low. GRADE was assessed using http://gradepro.org.

Data Synthesis

A meta-analysis was planned to pool relevant data from the included studies. However, given the high clinical heterogeneity among studies (ie, different muscle measurement methods, such as ultrasonography, computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging, and diverse treatments) a qualitative analysis was conducted.

Since some included studies did not report within- or between-group treatment effects, secondary-analyses were conducted using Review Manager (RevMan 5.3) to compare within- and between-group differences, as well as the corresponding mean differences (MD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) in primary outcomes using methods (ie, calculating mean change in each group by subtracting post-intervention mean from baseline mean or calculating mean differences between two groups using post-intervention measurements) recommended in the Cochrane handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention.42 To facilitate the comparisons of LMM volume, CSA and pain intensity among studies, the measurement unit in cm3, cm2 and cm were converted into mm3, mm2 and mm, respectively. Minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for pain, which means the smallest change in pain that a patient considers clinically meaningful, was set at 20mm on visual analogue scale (VAS).43 Minimal detectable change at 95% confidence (MDC95) was used to indicate the post-treatment change in scores that exceeded the measurement error (ie, true change). For patients with LBP, the MDC95 for LMM CSA, resting and contracted thickness was 100mm2,44 3.6mm,35 and 1.8mm,35 respectively. The MDC95 for percent thickness change during contraction was 15.7%.35

Results

Study Selection

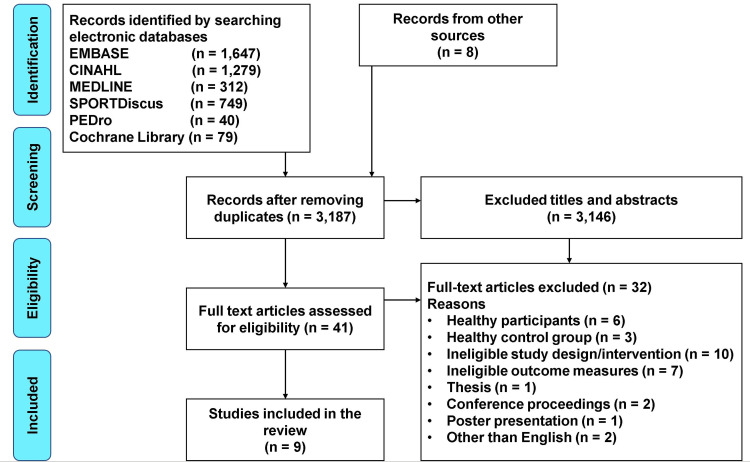

The search yielded 4114 citations. Nine RCTs were included from 41 screened full-text articles (Figure 1). The 2 reviewers demonstrated good agreements in selecting relevant papers at the first (κ=0.68) and second stages of screening (κ=0.76) (Appendix 3).

Figure 1.

A flow diagram of the literature search.

Characteristics of the Included Studies

The 9 included RCTs were published between 1996 and 2020, involving 451 participants (410 chronic, 41 acute LBP). The mean ages of participants ranged from 3145 to 50.846 years. The effectiveness of MCE (focusing on the activation of deep trunk muscles in different positions)2,24,29,30,45–49 in restoring normal LMM morphology or decreasing LBP were compared with McKenzie exercise,29 general exercise,2,30 general physiotherapy (eg, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), therapeutic ultrasound therapy, infrared radiation, and traction),2,46–48 massage,46 high-load lifting exercise,24 general strengthening plus aerobic exercises49 and analgesics45,46 (Appendix 4). The number of MCE sessions ranged from 12 to 36. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of these studies. These RCTs had either 2,2,24,29,30,45,48,49 3,47 or 4 treatment arms.46 Five studies involved a combination of one or two treatments with MCE in at least one arm2,45–47,49 (eg, MCE plus massage,46 MCE plus TENS,46 MCE plus general physiotherapy,2,47 MCE plus manual therapy49 and MCE plus analgesics45,46).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Publications | Case Definition | Age (Mean ± SD); Sample/Sex | Treatment (Frequency, Duration, and Duration/Session) | Outcome Measures | LMM Parameters | Measurement Method | Measurement Time Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akbari et al, 200830 | Chronic LBP >3 months |

MCE: 39.6 ± 3.5 yrs; n = 25 GE: 40 ± 3.6 yrs; n = 24 |

8 wks, 2x/wk, 30 mins | Pain VAS BPS. |

LMM resting thickness (L4–5) | USG | Baseline, 8 wks |

| Berglund et al, 201724 | Chronic LBP >3 months |

MCE: 43.3 ± 10.3 yrs; M/F = 13/20 HLL: 42.3 ± 9.8 yrs; M/F = 15/17 |

12 sessions over 2 months. | Pain VAS | LMM resting thickness on both sides of L5 vertebra | USG | Baseline, 2 months |

| Hides et al, 199645 | Acute LBP <3 weeks |

MCE + analgesics: 30.9 ± 6.5 yrs; M/F = 8/13. Analgesics: 31 ± 7.9 yrs; M/F = 10/10 |

4 wks and 10 wk | MPQ; pain VAS; daily pain diaries; RMDQ; lumbar ROM; habitual activity levels |

LMM CSA (L2 to S1) | USG | Baseline, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 10 wks |

| Hosseinifar et al, 201329 | Chronic LBP >3 months |

MCE: 40.1 ± 10.8 yrs; n = 15 McKenzie: 36.6 ± 8.2 yrs; n = 15 |

6wks, 3x/wk, 60 mins | Pain VAS; FRIQ | Rt & Lt LMM resting and contracted thickness (L4-5) | USG | Baseline, 6 wks |

| Kehinde et al, 201446 | Chronic LBP (unclear definition) |

MCE: 45.84 ± 9.95 yrs; n = 31 MCE + TENS: 45.84 ± 9.95 yrs; n = 31 MCE + massage: 44.57 ± 11.82 yrs; n = 30 Analgesics: 50.83 ± 13.03 yrs; n = 30 |

8 wks, 2x/wk | LMM contracted thickness (L4-5) | USG | Baseline, 8 wks | |

| Kim and Kim, 201347 | Chronic LBP 3 months |

GPT: 39.6 ± 6.2yrs; n = 10 GPT + MCE using sling: 39.9 ± 5.8 yrs; n = 10 GPT + MCE using sling + pushups: 40.5 ± 5.4 yrs; n = 10 |

6 wks,3x/wk,30 minutes. | ODI, surface electromyographic | LMM CSA on both sides (level was not reported) | CT | Baseline, 2, 4, and 6 wks |

| Lee et al, 201148 | Chronic LBP (unclear definition) |

MCE with a gymnastic ball: 32.7 ± 5.9 yrs; n = 17 GPT: 33.1 ± 5.7 yrs; n = 16 |

12 wks, 3x/wk, 45 mins | Pain VAS | LMM CSA (L4-5) | CT | Baseline,12 wks |

| Nabavi et al, 20182 | Chronic LBP >12 weeks |

MCE + GPT: 40.8 ± 8.2 yrs; n = 20 GE + GPT: 34.1 ± 10.8 yrs; n = 21 Noted: GPT = US, TENS, IRR |

4wks, 3x/wk | Pain VAS | LMM resting thickness. (Rt & Lt) at L5 LMM CSA (Rt& Lt) at L5 |

USG | Baseline, 4 wks |

| Tagliaferri et al, 202049 | Chronic LBP >3 months |

MCE + Manual therapy: 34.6 ± 7.2 yrs; n = 20 GSA: 34.8 ± 4.9 yrs; n = 20 |

MCE + Manual therapy: 1–3 months, 10 sessions, 30 mins;4–6 months, 2x30 mins session GSA: 1–3 months,2x/wk, 60 mins 4–6 months, 1–2x/wk, 60 mins. 1–6 months,3x/wk,20–40min |

Pain VAS, ODI, SF-36, isometric trunk extension, isometric trunk flexion, 1-RM leg press, leg press endurance, peak oxygen consumption | LMM volume (L1-L5) | MRI | Baseline, 3 months, and 6 months |

Abbreviations: BPS, back performance scale; CSA, cross-sectional area; CT, computed tomography; FRIQ, functional rating index questionnaire; GE, general exercises; GPT, general physiotherapy; GSA, general strengthening and aerobic exercises; HLL, high load lifting; IRR, infrared radiation; LBP, low back pain; LMM, lumbar multifidus muscle; Lt, left; MCE, motor control exercise; M/F, male/female; mins, minutes; MPQ, McGill pain questionnaire; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; ODI, Oswestry disability index; RMDQ, Roland Morris Disability questionnaire; ROM, range of motion; Rt, right; SF-36, 36-Item short-form health survey; US, ultrasound therapy; USG, ultrasonography; VAS, visual analogue scale; wk, weeks; x/wk, times per week; yrs, years; 1-RM, one-repetition maximum.

Ultrasonography,2,24,29,30,45,46 CT-scans47,48 or magnetic resonance imaging49 were used to image LMM morphology in the included studies. Most studies measured bilateral CSA,2,45,49 resting thickness,2,24,29,30 and contracted thickness29,46 from ultrasound and magnetic resonance images. Other studies measured CSA from CT images.47,48 Although the current study aimed to extract morphometric data from each vertebral level, only one included study reported the CSA of LMM from each of the 5 lumbar levels (L1 to L5).49 Similarly, only 1 included study reported the LMM volume of each lumbar level from L1 to L5.49 Although LMM morphometry on the painful side might differ from non-painful side,14,50 most of the included studies did not specify the side of measurements. These studies reported the post-treatment morphometric changes in LMM in terms of percentage or actual dimensions. Given the diverse treatment combinations and LMM morphometry measurement methods in the included studies, the planned meta-analysis was not conducted.

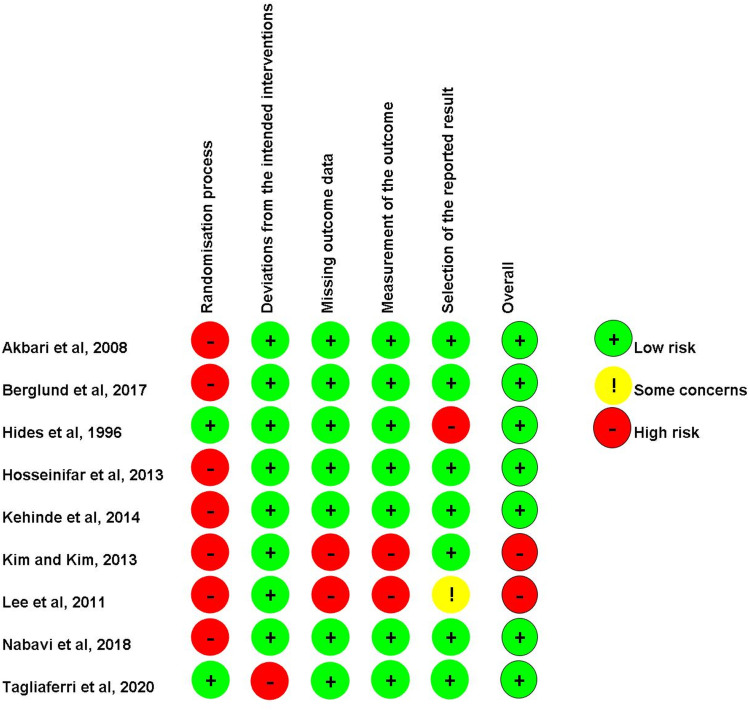

Risk of Bias

Risk of bias assessment for individual trials is presented in Figure 2. Seven studies2,24,29,30,45,46,49 were considered to have a low risk of bias, while two47,48 were deemed to have a high risk of bias.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias assessment according to Cochrane Collaboration’s tool (RoB 2.0) for randomized controlled trial.

Effects of MCE on LMM Morphology

The quality of evidence and details of the effectiveness of MCE in restoring normal LMM morphology are presented in Appendix 5 and Table 2, respectively.

Table 2.

Effect of Motor Control Exercise on the Morphometry of Lumbar Multifidus Muscle

| Publications | Interventions | Durations | Within-Group Change in Morphology | Between-Group Differences (MD (95% CI) s |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMM volume | ||||

| Tagliaferri et al, 202049 | Gp1: MCE + manual therapy Gp2: GSC MRI – L1-L5 |

Gp1: 3 months:10 sessions, 30 mins. 4–6 months 2x/wk, 30 mins. Gp2: 3 months: 2x/wk, 60 mins 4–6 months: 1–2x/wk, 60 mins. 6months: 3x/wk, 20–40min |

Changes from baseline to 3 months (L1-L5 volume) Gp1 mean changes (95% CI): at 3 months = −200mm3 (−700 to 300mm3), (p = 0.477) Gp2 mean changes (95% CI): at 3 months = 400mm3 (−100 to 1000mm3), (p = 0.102) No significant increase in LMM volume from L1-L5 in both the groups at 3 months Changes from baseline to 6 months (L1-L5 volume) Gp1 mean changes (95% CI): at 6 months = 200mm3 (−300 to 700mm3), (p = 0.463) Gp2 mean changes (95% CI): at 6 months = 800mm3 (300 to 1300mm3), (p = 0.003) Only Grp 2 demonstrated significant increases in LMM volume from L1-L5 at 6 months. |

Between-group analysis (Gp2-Gp1) At 3 months MD (95% CI) = 600mm3 (−100 to 1400mm3), (p = 0.096) At 6 months MD (95% CI) = 600mm3 (−100 to 1400mm3), (p = 0.116) No significant between-group differences in LMM volume at 3 and 6 months. |

| LMM CSA | ||||

| Hides et al, 199645 | Gp1: MCE + drugs Gp2: Drugs only USG - L2-S1 |

4 wks and 10wks | The difference between the sides at the most affected vertebral level was expressed as a percentage of CSA for the unaffected side at that level. Gp1: at 4thwk = 0.71 ± 2.49%, at 10th wk = 0.24 ± 3.29% Gp2: at 4th wk = 16.84 ± 9.26%; at 10th wk =14.02 ± 6.31% Since percentage changes in CSA were reported, MDC95 could not be used for comparisons |

Significantly greater post-treatment increases in LMM CSA on the painful side in Gp1 than Gp2 at 4th week FU (p = 0.0001) Since percentage changes in CSA were reported, MDC95 could not be used for comparisons. |

| Kim and Kim 201347 | Gp1: GPT Gp2: MCE using sling + GPT Gp3: MCE using sling + GPT + pushups CT scan (level was not reported) |

6 wks, 3x/wk, 30 mins | Change from baseline to 6 wks Gp1 mean change: Rt LMM = −0.2 ± 0.5mm2, Lt LMM = 0.2 ± 0.5mm2 (p > 0.05) Gp2 mean change: Rt LMM = 11.2 ± 3.2mm2, Lt LMM = 11.5 ± 3.8mm2 (p < 0.01). Gp3 mean change: Rt LMM = 7.0 ± 2.1mm2, Lt LMM = 7.5 ± 2.0mm2 (p < 0.01). Significant increase in LMM CSA in Gp2 and Gp3 Changes in all groups did not exceed MDC95 |

Post-treatment LMM CSA in Gp2 > Gp3; Rt (p < 0.001), Lt (p < 0.01). Secondary analysis, MD (95% CI) Rt LMM Gp2 minus Gp1= 11.4mm2 (9.4 to 13.4mm2), (p < 0.00001) Gp3 minus Gp1 = 7.2mm2 (5.9 to 8.5mm2), (p < 0.00001) Gp2 minus Gp3 = 4.2mm2 (1.83 to 6.57 mm2), (p = 0.0005) Lt LMM Gp2 minus Gp1 = 11.3mm2 (8.9 to 13.68mm2), (p < 0.0000) Gp3 minus Gp1 = 7.3mm2 (6.02 to 8.58mm2), (p < 0.00001) Gp2 minus Gp3 = 4mm2 (1.34 to 6.7mm2), (p = 0.003) Between-group changes in all groups did not exceed MDC95 |

| Lee et al, 201148 | Gp1: MCE on a gymnastic ball Gp2: GPT Axial CT scan - L4-5 |

12 wks, 3 d/wk, 45 mins | Change from baseline to 12 wks Gp1 mean change at L4-L5 = 121.0 ± 43.0mm2, (p < 0.05) Gp2 mean change at L4-L5 = 3.3 ± 18.3mm2, (p > 0.05) Significant increase in LMM CSA in Gp1 only. Change in Gp1 exceeded MDC95 |

Reported between-group analysis: (p < 0.05) Secondary analysis Gp1 minus Gp2 = 120mm2 (100–140mm2) Gp1 had a greater effect than Gp2, which exceeded MDC95 |

| Nabavi et al, 20182 | Gp1: MCE + GPT Gp2: GE + GPT USG - L5 |

4wks, 3x/wk | Change from baseline to 4 wks Gp1 mean change (95% CI): Rt LMM CSA = 0.4mm2 (0.2 to 0.6mm2) (p = 0.01); Lt LMM CSA= 0.5mm2 (0.2 to 0.8mm2) (p = 0.01) Gp2 mean change (95% CI): Rt LMM CSA = 0.3mm2 (0.0 to 0.6mm2) (p = 0.081); Lt LMM CSA = 0.2mm2 (0.1 to 0.5mm2) (p = 0.045). Changes in both groups were smaller than MDC95 |

Reported between-group analysis. (Gp1 minus Gp2): Rt LMM = 0.1mm2 (−0.1 to 0.2mm2) (p = 0.86) Lt LMM = 0.3mm2 (−0.1 to 0.2mm2) (p = 0.66) No significant between-group changes were noted in bilateral LMM CSA Between-group differences were smaller than MDC95 |

| Tagliaferri et al, 202049 | Gp1: MCE + manual therapy Gp2: GSA MRI – L1-L5 |

Gp1: 3 months:10 sessions, 30 mins 4–6 months 2x/wk, 30 mins Gp2: 3 months: 2x/wk, 60 mins 4–6 months: 1–2x/wk, 60 mins 6months: 3x/wk, 20–40min |

Changes from baseline to 3 months at different levels Gp1 mean changes (95% CI): L1 = −10.2mm2 (−18.8 to −1.6mm2), (p = 0.019); L2 = −10.0mm2 (−21.3 to 1.0mm2), (p = 0.052); L3 = −9.1mm2 (−37.0 to 18.8mm2), (p = 0.521); L4 = −13.9mm2 (−47.3 to 19.6mm2), (p = 0.416); L5 = −3.0mm2 (−29.7 to 23.9mm2), (p = 0.831) Gp2 mean changes (95% CI): L1 = 9.7mm2 (−2.3 to 21.6mm2), (p = 0.112); L2 = 12.2mm2 (−8.6 to 33.0mm2), (p = 0.251); L3 = 9.9mm2 (−9.6 to 29.5mm2), (p = 0.318); L4 = 23.7mm2 (−6.1 to 53.5mm2), (p = 0.119); L5 = 37.7mm2 (11.2 to 64.2mm2), (p = 0.005) Significant increase in LMM size at L1 at 3 months in Gp1 Significant increase in LMM size at L5 at 3 months in Gp2 Changes from baseline to 6 months at different levels Gp1 mean changes (95% CI): L1 = −2.8mm2 (−11.6 to 6.0mm2), (p = 0.529); L2 = −9.0mm2 (−20.0 to 2.0mm2), (p = 0.109); L3 = −0.0mm2 (−28.6 to 28.6mm2), (p = 0.999); L4 = −5.8mm2 (−40.1 to 28.5mm2), (p = 0.741); L5 = 13.0mm2 (−14.5 to 40.4mm2), (p = 0.355) Gp2 mean changes (95% CI): L1 = 6.5mm2 (−5.5 to 18.5mm2), (p = 0.287); L2 = 3.8mm2 (−17.0 to 24.6mm2), (p = 0.721); L3 = 26.3mm2 (6.7 to 45.8mm2), (p = 0.008); L4 = 37.8mm2 (8.0 to 67.6mm2), (p = 0.013); L5 = 46.0mm2 (19.5 to 72.5mm2), (p = 0.001) Significant increase in LMM size at L3, L4 and L5 at 6 months in Gp2 only Changes in both groups were smaller than MDC95 at 3 and 6 mon ths. |

Between group differences at different levels At 3 months L1 = 19.9mm2 (5.0 to 34.8mm2), (p = 0.009) L2 = 23.1mm2 (−0.8 to 47.1mm2), (p = 0.058) L3 = 19.1mm2 (−14.5 to 52.8mm2), (p = 0.266) L4 = 37.6mm2 (−7.1 to 82.3mm2), (p = 0.099) L5 = 40.6mm2 (2.9 to 78.3mm2), (p = 0.035) Significant increase in LMM size was noted at L1 and L5 at 3 months in Gp2 compared to Gp1. At 6 months L1 = 9.3mm2 (−5.7 to 24.4mm2), (p = 0.225) L2 = 13.2mm2 (−11.1 to 37.4mm2), (p = 0.287) L3 = 26.3mm2 (−7.8 to 60.4mm2), (p = 0.130) L4 = 43.6mm2 (−1.7 to 88.9mm2), (p = 0.059) L5 = 33.0mm2 (−5.1 to 71.2mm2), (p = 0.090) No significant between-group differences in LMM size from L1 to L5 at 6 months were noted. |

| Resting thickness | ||||

| Akbari et al, 200830 | Gp1: MCE Gp2: GE USG - L4-5 |

8 wks, 2x/wk, 30 mins | Gp1 mean ± SD: pre = 8.6 ± 2.4mm; post = 9.7 ± 2.5mm (p < 0.01) Gp2 mean ± SD: pre = 8.8 ± 1.5mm; post = 9.3 ± 1.6mm (p < 0.01) Significant increase in resting LMM thickness in both the groups were noted. Secondary analysis (post minus pre) Gp1 = 1.1mm (−0.3 to 2.5mm), (p = 0.11) Gp2 = 0.5mm (−0.4 to 1.4mm), (p = 0.26) Changes in both groups did not exceed MDC95 |

Between-group analysis data was not reported. Secondary analysis Gp1 minus Gp2 = 0.4mm (−0.8 to 1.6mm) (p = 0.61) No significant between-group difference was noted. Between-group difference was smaller than MDC95 |

| Berglund et al, 201724 | Gp1: MCE Gp2: HLL USG - L5 |

12 sessions over 2 months | Gp1 mean ± SD: Larger side: pre = 2.7 ± 0.4mm; post = 2.7 ± 0.5mm; % change = 0.4 ± 18.0% Smaller side: pre = 2.5 ± 0.4mm; post = 2.6 ± 0.5mm; % change = 8.0 ± 20.9% Gp2 mean ± SD: Larger side: pre = 2.6 ± 0.5mm; post = 2.7 ± 0.6mm; % change = 1.7 ± 14.1% Smaller side: pre = 2.4 ± 0.5mm; post = 2.7 ± 0.5mm; % change = 11.2 ± 18.1% Increases in LMM thickness on the smaller side > the larger side in both groups (p = 0.001) Secondary analysis (post minus pre) Gp1: Larger side = 0mm (−0.2 to 0.2mm), (p = 1); Smaller side = 0.1mm (−0.1 to 0.3mm), (p = 0.37) Gp2: Larger side = 0.1mm (−0.2 to 0.4), (p = 0.47); Smaller side = 0.3mm (0.1 to 0.5), (p = 0.02) Changes for all groups were smaller than MDC95 |

No significant between-group difference for both sides were reported (p = 0.495) Secondary analysis (Gp1 minus Gp2) Larger side = 0.0mm (−0.3 to 0.3mm) Smaller side = −0.1mm (−0.3 to 0.1mm) Between-group changes were smaller than MDC95 |

| Hosseinifar et al, 201329 | Gp1: MCE Gp2: McKenzie exercise USG - L4-5 |

6wks, 3x/wk, 60 mins | Gp1 mean ± SD: Rt LMM pre = 30.0 ± 2.9mm, post = 31.5 ± 4.8mm (p < 0.05); Lt LMM pre = 30.8 ± 4.6mm, post = 32.6 ± 4.8mm (p < 0.05). Gp2 mean ± SD: Rt LMM pre = 29.4 ± 5.9mm, post = 31.1 ± 5.7mm (p < 0.05); Lt LMM pre = 29.7 ± 5.5mm, post = 31.1 ± 5.0mm (p < 0.05). Significant increases in resting Rt and Lt LMM thickness in Gp1 and Gp2 Secondary analysis (post minus pre) Gp1 MD (95% CI): Rt LMM = 1.5mm (−1.3 to 4.3mm), (p = 0.30); Lt LMM = 1.8mm (−1.6 to 5.1), (p = 0.29) Gp2 MD (95% CI): Rt LMM = 1.7mm (−2.5 to 5.9mm), (p = 0.42); Lt LMM = 1.4mm (−1.4 to 4.2mm), (p = 0.33) Changes in both groups were smaller than MDC95 |

Between-group analysis was not reported Secondary analysis (Gp1 minus Gp2) Rt LMM = 0.4mm (−3.4 to 4.2mm) (p > 0.05) Lt LMM = 1.5mm (−2.0 to 5.0mm) (p > 0.05) No significant between-group differences Between-group differences were smaller than MDC95 |

| Nabavi et al, 20182 | Gp1: MCE + GPT Gp2: GE + GPT USG - L5 |

4 wks, 3x/wk | Change from baseline to 4 wks Gp1 mean changes (95% CI): Rt LMM = 1.5mm (1.1 to 2.1mm) (p = 0.01); Lt LMM = 1.5mm (0.9 to 2.4mm) (p = 0.01) Gp2 mean changes (95% CI): Rt LMM = 1.8mm (1.0 to 2.2mm) (p = 0.01); Lt LMM = 1.7mm (0.8 to 2.5mm) (p = 0.01). Significant increase in bilateral resting LMM thickness in both the groups Changes in both groups were smaller than MDC95 |

Reported Between-group analysis (Gp2 minus Gp1): MD (95% CI): Rt LMM = 0.3mm (0.1to 0.5mm) (p = 0.53) Lt LMM = 0.2mm (0.0 to 0.4mm) (p = 0.64) No significant between-group differences in bilateral resting LMM thickness at L5 at the 4th wk Between-group differences were smaller than MDC95 |

| Contracted thickness | ||||

| Hosseinifar et al, 201329 | Gp1: MCE Gp2: McKenzie exercises USG - L4-5 |

6wks, 3x/wk, 60mins | Gp1 mean ± SD: Rt LMM pre = 36.3 ± 4.0mm, post = 37.8 ± 4.7mm; Lt LMM pre = 37.1 ± 3.9mm, post = 39.9 ± 4.4mm (p < 0.05) Gp2 mean ± SD: Rt LMM pre = 35.0 ± 6.2mm, post = 36.3 ± 5.2mm; Lt LMM pre = 36.6 ± 5.3mm, post = 37.4 ± 4.9 mm (p > 0.05) Significant increase in contracted Lt LMM thickness in Gp1 only Secondary analysis (post minus pre) Gp1: Rt LMM = 1.5mm (−1.6 to 4.6), (p = 0.35); Lt LMM = 2.8mm (−0.2 to 5.8), (p = 0.07) Gp2: Rt LMM = 1.3mm (−2.8 to 5.4), (p = 0.53); Lt LMM = 0.8mm (−2.9 to 4.5), (p = 0.67) Change in Lt LMM in Gp1 exceeded MDC95 |

Between-group analysis was not reported Secondary analysis (Gp1 minus Gp2) Rt LMM = 1.5mm (−2.1 to 5.1mm), (p = 0.41) Lt LMM = 2.5mm (−0.8 to 5.8mm), (p = 0.14) No significant between-group difference was noted. Between-group difference in the changes of Lt LMM exceeded MDC95 |

| Kehinde et al, 201446 | Gp1: MCE Gp2: MCE + TENS. Gp3: MCE + massage. Gp4: analgesics USG - L4-5 |

8 wks, 2x/wk | Gp1 mean ± SD: pre = 2.7 ± 0.7mm, post = 3.2 ± 0.7mm (p = 0.01) Gp2 mean ± SD: pre = 2.8 ± 0.5mm, post = 3.3 ± 0.5mm (p = 0.01) Gp3 mean ± SD: pre = 2.7 ± 0.6mm, post = 3.0 ± 0.5mm (p = 0.01) Gp4 mean ± SD: pre = 2.9 ± 0.6mm, post = 3.0 ± 0.5mm (p = 1.00) Significant increase in contracted LMM thickness at L4-L5 at 8 wk in Gps1, 2 and 3 only Secondary analysis (post minus pre) Gp1 = 0.5mm (0.2 to 0.9mm), (p = 0.005) Gp2 = 0.5mm (0.3 to 0.8mm), (p < 0.0001) Gp3 = 0.3mm (0.0 to 0.6mm), (p = 0.04) Gp4 = 0.1mm (−0.2 to 0.4mm), (p = 0.48) Changes for all groups were smaller than MDC95 |

Between-group analysis was not reported. Secondary analysis Gp1 minus Gp3 = 0.2mm (−0.1 to 0.5mm), (p = 0.20) Gp1 minus Gp4 = 0.2mm (−0.1 to 0.5mm), (p = 0.20) Gp1 minus Gp2 = −0.1mm (−0.4 to 0.2mm), (p = 0.52) Gp2 minus Gp3 = 0.3mm (0.1 to 0.6mm), (p = 0.02) Gp2 minus Gp4 = 0.3mm (0.1 to 0.6mm), (p = 0.02) Gp3 minus Gp4 = 0.0mm (−0.3 to 0.3mm), (p = 1.00) Significant increase in contracted LMM thickness was noted in Gp2 compared to Gp1, Gp3 and Gp4 Between-group differences were smaller than MDC95 |

Note: The bold values indicate that the changes exceeded MDC95.

Abbreviations: CSA, cross-sectional area; CT, computed tomography; d/wk, days per week; FU, follow up; GE, general exercises; Gp, group; GPT, general physiotherapy; GPT, general physiotherapy; GSA, general strengthening and aerobic exercises; HLL, high load lifting; IRR, infrared radiation; LMM, lumbar multifidus muscle; Lt, left; MCE, motor control exercise; MD (95% CI), mean difference (95% confidence intervals); MDC95, minimal detectable change at 95% confidence interval; mins, minutes; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; Rt, right; SD, standard deviation; TENS, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation; US, therapeutic ultrasound therapy; USG, ultrasonography; wk, week.

Volume of LMM

Only one study49 with low risk of bias investigated the effects of MCE plus manual therapy on the volume of LMM.

Within-Group Comparisons

Low-quality evidence suggested that 10 sessions of MCE plus manual therapy did not significantly increase the volume of LMM in comparison to general strengthening plus aerobic exercises.49

Between-Group Comparisons

Low-quality evidence suggested that 10 sessions of MCE plus manual therapy were not significantly better than general strengthening plus aerobic exercises in increasing LMM volume.49

CSA of LMM

Three studies2,45,49 with low and two47,48 with high risk of bias investigated the effects of MCE on LMM CSA.

Within-Group Comparisons

Very low- to low-quality evidence substantiated that 12 sessions or more MCE with or without adjunct treatments (eg, resistance training, TENS, massage, manual therapy) significantly increased CSA of LMM at multiple lumbar levels.2,45,47–49 Similarly, there was very low- to low-quality evidence that 36 sessions of MCE caused post-treatment increases in LMM CSA by 121 mm2, which exceeded MDC9548 (Table 2).

Between-Group Comparisons

Low-quality evidence supported that MCE along with analgesics induced significantly greater increases in LMM CSA than analgesic alone among patients with acute LBP.45 Likewise, there was very low-quality evidence that 18 or more sessions of MCE or MCE plus general physiotherapy caused significantly greater increases in LMM CSA than general physiotherapy alone in patients with CLBP.47,48 However, only 36 sessions of MCE induced significantly greater increase in LMM CSA that exceeded MDC95 (by 120 mm2) than general physiotherapy in patients with CLBP (Table 2).48 However, there was low-quality evidence that 12 sessions of MCE plus general physiotherapy/MCE plus manual therapy were not significantly different from 12 sessions of general exercise plus general physiotherapy/general strengthening plus aerobic exercises in altering LMM CSA.2,49

Resting LMM Thickness

Four studies2,24,29,30 examined changes in the resting LMM thickness at the L4-5 level among patients with CLBP. The treatments ranged from 2 to 3 days/week, with 30–60 minutes each for 4 to 8 weeks. All four studies demonstrated a low risk of bias.2,24,29,30

Within-Group Comparisons

Very low- to low-quality evidence suggested that 12 to 18 sessions of MCE with/without adjunct treatment, general exercises, high-load lifting, McKenzie exercise, or general exercises plus general physiotherapy significantly increased resting LMM thickness.2,24,29,30 Although these post-MCE increases in the resting LMM thickness ranged from 1.1mm to 1.8mm, they did not exceed MDC95.2,29,30 (Table 2).

Between-Group Comparisons

There was very low- to low-quality evidence that 12 to 18 sessions of MCE or MCE plus general physiotherapy were not significantly better than other treatments (eg, general exercises,30 high load lifting exercise,24 McKenzie exercise,29 general exercise plus physiotherapy,2 in increasing LMM resting thickness (Table 2).

Contracted LMM Thickness

Two studies with low risk of bias29,46 evaluated the effects of 16 to 18 sessions of MCE on the contracted thickness of LMM at the L4-5 level in patients with CLBP.

Within-Group Comparisons

Low-quality evidence suggested that MCE with/without adjunct treatment significantly increased the contracted thickness of LMM ranging from 0.3mm to 2.8mm.29,46 However, only 18 sessions of MCE caused significant increases in contracted thickness of left LMM that exceeded MDC95 (Table 2).29

Between-Group Comparisons

There was low-quality evidence that MCE was comparable to McKenzie exercise in increasing LMM contracted thickness.29 Low-quality evidence suggested that although MCE plus TENS caused significantly greater increases in contracted LMM thickness than MCE plus massage or analgesic alone, the differences did not exceed MDC95 (Table 2).46

Effects of MCE on Percent LMM Thickness Changes During Contraction and LMM Fatty Infiltration

Despite the comprehensive search, no RCT investigated the effects of intervention on percent LMM thickness changes during contraction or LMM fatty infiltration.

Effects of MCE on LBP Intensity of the Included Studies

Of the 9 included RCTs, 7 trials reported post-treatment decreases in LBP intensity (Table 3). Seven included studies2,24,29,30,45,48,49 used VAS to measure LBP intensity, which comprises a 10cm straight line with the two endpoints indicating no pain (0cm) and maximum pain (10cm), respectively.51

Table 3.

Effect of Motor Control Exercise on Low Back Pain

| Publications | Interventions | Pain Measures | Within-Group Change in Pain | Between-Group Differences (MD (95% CI) s |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akbari et al, 200830 | Gp1: MCE Gp2: GE |

VAS (mm) | Gp1 mean ± SD: pre = 7.3 ± 1.0mm, post = 2.5 ± 1.2mm, (p = 0.0001) Gp2 mean ± SD: pre = 8 ± 1.2mm, post = 4 ± 1.5mm, (p = 0.0001) Secondary analysis (pre minus post) Gp1 = 4.8mm (4.19 to 5.41mm), (p < 0. 00001) Gp2 = 4mm (3.23 to 4.77mm), (p < 0.00001) Significant post-treatment reduction in LBP in Gp1 and Gp2. Significant post-treatment reduction in LBP in Gp1 and Gp2. Changes for both groups were smaller than MCID |

Between-group analysis data was not reported. Reported p value (p = 0.015) Secondary analysis Gp1 minus Gp2 = −1.5mm (−2.26 to 0.74mm) (p = 0.0001) Gp1 showed significantly larger decreases in LBP than Gp2 Between-group difference was smaller than MCID |

| Berglund et al, 201724 | Gp1: MCE Gp2: High load lift exercise |

VAS (mm) | Gp1 mean ± SD: pre = 48.7 ± 27.0mm, mean change ± SD at 2 months: −18.5 ± 26.7mm, (p value was not reported) Gp2 mean ± SD: pre = 41.3 ± 23.8mm, mean change ± SD at 2 months: −19.0 ± 25.5mm, (p value was not reported) Significant post-treatment reduction in LBP in Gp1 and Gp2. Changes for both groups were smaller than MCID |

Between-group analysis data was not reported. Reported p value (p = 0.95) Secondary analysis Gp1 minus Gp2 = 0.5mm (−12.71 to 13.71mm) (p = 0.94) No significant post-treatment differences between Gp1 and Gp2 |

| Hides et al, 199645 | Gp1: MCE plus drugs (analgesics + nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory) Gp2: Drugs |

VAS (mm) | Significant decreases in pain intensity in both groups. (Values were not reported) | No significant difference between the two groups from 1 to 4 weeks (p = 0.96) LBP assessment at 10th wk was not reported. |

| Hosseinifar et al, 201329 | Gp1: MCE Gp2: McKenzie exercise |

VAS (mm) | Gp1 mean ± SD: pre = 4.3 ± 1.6mm, post = 1.5 ± 1.4mm, (p < 0.05) Gp2 mean ± SD: pre = 4.4 ± 2.0mm, post = 2.7 ± 1.4mm, (p < 0.05) Secondary analysis (pre minus post) Gp1 = 2.8mm (1.72 to 3.88mm), (p < 0. 00001) Gp2 = 1.7mm (0.46 to 2.94mm), (p < 0.00001) Significant post-treatment reduction in LBP in Gp1 and Gp2 Changes for both groups were smaller than MCID |

Between-group analysis data was not reported. Reported p value (p < 0.05) Secondary analysis Gp1 minus Gp2 = −1.20mm (−2.20 to −0.20mm) (p = 0.02) Gp1 showed significantly larger decreases in LBP than Gp2. Between-group difference was smaller than MDC95 |

| Lee et al, 201148 | Gp1: MCE on a gymnastic ball Gp2: GPT |

VAS (mm) | Gp1 mean ± SD: pre = 59mm ± 19mm, post at 12th wk = 13 ± 11mm, (p < 0.05) Gp2 mean ± SD: pre = 56mm ± 20mm, post at 12th wk = 21 ± 15mm, (p < 0.05) Secondary analysis (pre minus post) Gp1 = 46mm (45.56 to 56.44mm), (p < 0.00001) Gp2 = 35mm (22.75 to 47.25mm), (p < 0.00001) Significant post-treatment reduction in LBP in Gp1 and Gp2 Within-group changes in both groups exceeded MCID |

Between-group analysis was not reported Secondary analysis Gp1 minus Gp2 = −8mm (−17.02 to 1.02mm) (p = 0.08) No significant difference between Gp1 and Gp2 at the 12th wk Between-group difference was smaller than MCID |

| Nabavi et al, 20182 | Gp1: MCE plus GPT Gp2: GE plus GPT |

VAS (mm) |

Gp1 MD (95% CI): 33mm (22 to 43mm), post-treatment decreases in LBP (p = 0.01) Gp2 MD (95% CI): 35mm (22 to 41mm), post-treatment decreases in LBP (p = 0.01) Significant post-treatment reduction in LBP in Gp1 and Gp2 Within-group changes in both groups exceeded MCID |

Between-group differences: (p = 0.82) Gp2 minus Gp1 = 2.0mm (0.2 to 3.4mm) (p = 0.82) No significant difference between Gp1 and Gp2 Between-group difference was smaller than MCID |

| Tagliaferri et al, 202049 | Gp1: MCE + manual therapy Gp2: GSA |

VAS (mm) | Gp1: Significant decrease in LBP at 6 (p < 0.05), 8 (p < 0.01), 10 (p < 0.001), 12 (p < 0.001), 14 (p < 0.001), 16 (p < 0.001), 18 (p < 0.01), 20 (p < 0.001), 20 (p < 0.001), 22 (p < 0.001), and 24 (p < 0.001) weeks. Gp2: Significant decrease in LBP at (p < 0.05), 8 (p < 0.05), 10 (p < 0.05), 12 (p < 0.01), 18 (p < 0.01), 20 (p < 0.05), 22 (p < 0.05), 24 (p < 0.01). Significant post-treatment reduction in LBP at 6 months in both Gp1 (p < 0.001) and Gp2 (p = 0.008) |

Gp1 was better than Gp2 in decreasing LBP at 14 and 16 weeks (p = 0.003) No significant difference between Gp1 and Gp2 at 6 months |

Note: The bold values indicate the within-group changes exceeded minimal clinical important difference.

Abbreviations: 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; FU, follow up; GE, general exercises; Gp, group; GPT, general physiotherapy; GSA, general strengthening and aerobic exercises; HLL, High load lifting; LBP, low back pain; MCE, motor control exercise; MCID, minimal clinical important difference; mins, minutes; mm, millimeter; SD, standard deviation; VAS, visual analogue scale; wk, week.

Within-Group Comparisons

There was very low- to low-quality evidence that 4 to 24 weeks of MCE,30 McKenzie exercise,29 general exercises,30 high-load lifting exercises,24 MCE plus manual therapy,49 general strengthening plus aerobic exercises,49 and general physiotherapy2,48 significantly decreased pain. The average pain reduction following MCE alone ranged from 2.8mm to 18.5mm on VAS, which were smaller than MCID.24,29,30 There was very low- to low-quality evidence that combining MCE or general exercises with general physiotherapy,2 MCE on a gymnastic ball or general physiotherapy alone48 significantly reduced CLBP intensity by 33mm to 46mm on VAS, which exceeded the MCID for pain using VAS (>20mm) (Table 3).43 Similarly, low-quality evidence supported that MCE with analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs significantly reduced acute LBP, although the extent of pain reduction was not reported.45

Between-Group Comparisons

There was low-quality evidence that MCE alone caused significantly greater CLBP reduction than general exercise alone,30 or McKenzie exercise alone.29 However, there was no evidence that MCE with or without adjunct treatments was significantly better than high load lift exercise,24 general physiotherapy,48 general strengthening plus aerobic exercises,49 general exercise plus general physiotherapy,2 or drug alone45 in reducing acute or chronic LBP. Given the high clinical heterogeneity among studies, meta-analysis was not conducted.

Temporal Relations Between Changes in LMM Morphology and Changes in LBP Intensity or LBP-Related Disability

Only two included RCTs with low risk of bias investigated the correlations between changes in LMM morphology and the corresponding changes in LBP intensity among patients with acute (n=41)45 or CLBP (n=65).24 There was no evidence that post-treatment increases in LMM resting thickness24 or CSA45 were related to LBP reduction (Table 4). Likewise, no evidence suggested that post-treatment increases in LMM CSA were related to changes in Roland Morris Disability Index scores in patients with acute LBP45 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlation Between Post-Treatment Change in Lumbar Multifidus Muscle (LMM) Morphology and the Corresponding Changes in Low Back Pain (LBP) Intensity or LBP-Related Disability

| Publications | Interventions | Duration | Pain/Disability Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berglund et al, 201724 | Gp1: MCE Gp2: High load lift exercise |

2 months. | Visual analogue scale (cm) | No correlation between changes in LMM resting thickness and pain intensity (p = 0.411). |

| Hides et al, 199645 | Gp1: MCE plus drugs (analgesics + nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory) Gp2: Drugs |

4 weeks | Visual analogue scale (mm) | No significant correlation between changes in pain and increase of LMM CSA in Gp 1 (p value was not reported) No correlation analysis between changes in pain and LMM CSA in Gp 2 as there was no increase in CSA of LMM in Gp 2. LBP assessment at 10th wk was not reported. |

| Hides et al, 199645 | Gp1: MCE plus drugs (analgesics + nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory) Gp2: Drugs |

4 weeks | Roland Morris Disability Index | No significant correlation between changes in disability score and LMM CSA in Gp1. (p value was not reported) |

Abbreviations: cm, centimeter; CSA, cross-sectional area; Gp, group; LMM, lumbar multifidus muscle; MCE, motor control exercise; mm, millimeter.

Protocol Deviations from PROSPERO Registration

Although the original protocol planned to summarize evidence regarding the effectiveness of various physiotherapy interventions in restoring normal LMM morphology and reducing pain in patients with LBP, the search yielded diverse treatments. Since the initial review question was too broad and MCE was the most commonly studied LBP treatment, we narrowed it down to a more specific research objective. Therefore, the current review focused on the effectiveness of MCE in restoring normal LMM morphology and decreasing pain in people with low back pain.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review to summarize the evidence regarding the effects of MCE on LMM morphology, LBP, and the correlations between changes in LMM morphology and LBP intensity or LBP-related disability. Our findings suggest that MCE may be little or no better than other interventions in changing LMM morphology or decreasing pain intensity. Similarly, there is no correlation between changes in LMM morphology and LBP or LBP-related disability.

The weak effects of post-MCE changes in LMM morphology (eg, thickness or CSA) may be related to insufficient exercise dosages (ie, frequency, intensity, type, and duration of MCE). Sokunbi Oluwaleke et al found that thrice weekly MCE for 6 weeks caused significantly greater increases in LMM CSA than once weekly MCE.52 Exercise-induced skeletal muscle hypertrophy usually occurs after exercising for at least 6-weeks.53 Previous research has shown that muscle strengthening at 2–3 sessions per week yielded significantly greater CSAs of quadriceps and elbow flexors than exercising once-weekly.54 Our findings suggest that the number of treatment sessions rather than exercise types might elicit post-treatment LMM morphological changes. However, there was conflicting evidence regarding whether these post-treatment changes in CSA exceeded the measurement error. Future studies should investigate the dose–response relationship between MCE intervention frequency/duration/intensity and the corresponding changes in LMM morphometry at different lumbar levels to determine optimal treatment dosage.

Interestingly, MCE29,45 and high-load lifting exercises24 appear to selectively increase the resting thickness24 and contracted thickness24,29 of LMM on the painful side to reduce asymmetry, which is not uncommon among patients with acute12 /chronic LBP.14,50 However, since most of the studies had small sample sizes and short-treatment durations, future large-scale prospective studies with longer follow-ups are warranted to determine the long-term effect of MCE or high-load lifting exercises on restoring LMM symmetry among patients with acute/chronic LBP and to identify the mechanisms underlying the selective muscle hypertrophy.

The current review found low-quality evidence that there were no clinically important differences between MCE and other physiotherapy interventions in reducing CLBP. Our finding concurred with a prior meta-analysis55 and a Cochrane review,32 which revealed low- to high-quality evidence that MCE and other interventions had comparable effects on reducing non-specific LBP. However, these findings contradict another meta-analysis of eight studies, which concluded that MCE was more effective than general exercises in decreasing pain in patients with CLBP.56 The disparity might be ascribed to the differences in measurement scales used in studies to measure pain intensity, treatment duration and dosages, criteria used for exercise progression, and follow-up periods. The discrepancy in results might also be attributed to less patients (n=603) involved in Gomes-Neto et al's meta-analysis56 as compared to that of Smith et al55 (n=2258).

The current review found no evidence to support a significant correlation between changes in LMM morphology and changes in LBP or LBP-related disability.24,45 These findings differed from that of cohort studies, which found that patients with improved LBP displayed improved LMM morphometry (eg, increased percent thickness change during contraction).57,58 The discrepancy may be due to the fact that many prior studies only evaluated the immediate post-treatment changes in LMM morphology and LBP intensity without long-term follow-ups. It is plausible that post-treatment morphological changes may be transient or may take time to develop. Future RCTs should clarify the association between temporal changes in LMM morphometry and the corresponding changes in LBP/LBP-related disability at different follow-up time points.

Additionally, while multiple factors may affect the clinical outcomes of patients with CLBP (eg, depression, anxiety, fear avoidance, catastrophizing and sleep),59–61 all included RCTs in the current review did not adjust for these confounders in their analyses, which might have affected the reported temporal relations. Future studies should conduct path analyses to determine if LMM morphology may mediate or moderate LBP intensity/LBP-related disability after considering other potential confounders. The findings may help refine assessments and treatments for patients with LBP and concomitant aberrant LMM morphology.

Multiple factors may affect the measured LMM morphometry. First, since LMM thickness is a 2-dimensional measurement, changes in resting/contracted thickness as measured by ultrasonography can be affected by multiple factors (eg, the tightness of surrounding tissues, line of force, etc.).62 Therefore, LMM CSA measurements may be better to reveal morphometric changes. Second, LMM morphology as measured by ultrasonography is user dependent. The assessors’ experiences may affect the measured results. Unfortunately, all included RCTs did not report the test–retest reliability of their LMM measurements. Although the current review used previously reported MDC95 to determine whether the reported LMM morphometric changes exceed measurement errors, the actual measurement error in each study might differ. Third, changes in LMM CSA as measured on CT scans are not directly related to muscle function, although bigger CSAs are thought to be associated with greater muscle strength. Future studies should evaluate the effects of MCE on LMM function (eg, electromyographic activity) in addition to morphology.

Strengths and Limitations

This review had several strengths. Comprehensive literature searches in 6 databases, standardized screening, data extraction, and methodological quality assessments of the studies were performed to ensure proper extraction and evaluation of data. The study protocol was registered with PROSPERO, while the reporting of the review followed the PRISMA guideline to ensure credibility and comprehensiveness of data. Further, since this review only included RCTs, our conclusion was drawn based on studies with the highest level of evidence.

Our review had some limitations. First, given the heterogeneity of outcome measures, exercise intensity, and underreporting of the side of LMM morphology in the included studies, no meta-analysis was conducted. Future studies should standardize the reporting/definition of LMM morphology and interventions to enable meta-analyses. Second, the sample sizes of the RCTs were small, ranging from 3029,47 to 122,46 which might have limited the statistical power. Future research should estimate the sample size based on the effect sizes of existing studies to ensure sufficient power to detect post-treatment changes in LMM morphology. Third, only RCTs published in English were included. Future systematic reviews should include non-English publications to improve the generalizability of findings. Fourth, the mean age of participants in the RCTs ranged from 30.945 to 50.846 years. Our findings may not be generalized to younger/older patients with LBP.

Conclusions

There is preliminary evidence that MCE may change LMM morphology, although it may be dose dependent. Specifically, 36 or more sessions of MCE may increase LMM CSA in patients with CLBP. However, existing evidence does not support that MCE is more effective than other exercises in treating acute/chronic LBP. That said, future research is warranted to determine the effects of MCE on segmental or global morphometry (including intramuscular fatty infiltration) of LMM and clinical outcomes, as well as to quantify the causal relationships between changes in LMM morphology and LBP/LBP-related disability.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

This work was funded by Early Career Scheme (251018/17M). The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The content of the manuscript has not been published or submitted for publication elsewhere. There are no financial or other relationships that has a direct financial interest in any matter included in this manuscript. Jaro Karppinen reports personal fees from Pfizer, outside the submitted work. The authors report no other potential conflicts of interest for this work.

References

- 1.Koes B, Van Tulder M, Thomas S. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. BMJ. 2006;332(7555):1430–1434. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7555.1430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nabavi N, Mohseni Bandpei MA, Mosallanezhad Z, Rahgozar M, Jaberzadeh S. The effect of 2 different exercise programs on pain intensity and muscle dimensions in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018;41(2):102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2017.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vos T, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1211–1259. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32154-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2356–2367. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)30480-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Refshauge KM, Maher CG. Low back pain investigations and prognosis: a review. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(6):494–498. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.016659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodges PW, Richardson CA. Inefficient muscular stabilization of the lumbar spine associated with low back pain. A motor control evaluation of transversus abdominis. Spine. 1996;21(22):2640–2650. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199611150-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freeman MD, Woodham MA, Woodham AW. The role of the lumbar multifidus in chronic low back pain: a review. PM R. 2010;2(2):142–146; quiz 141 p following 167. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part II. Neutral zone and instability hypothesis. J Spinal Disord. 1992;5(4):390–397. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199212000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moseley GL, Hodges PW, Gandevia SC. Deep and superficial fibers of the lumbar multifidus muscle are differentially active during voluntary arm movements. Spine. 2002;27(2):E29–E36. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200201150-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belavy DL, Armbrecht G, Richardson CA, Felsenberg D, Hides JA. Muscle atrophy and changes in spinal morphology: is the lumbar spine vulnerable after prolonged bed-rest? Spine. 2011;36(2):137–145. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181cc93e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danneels LA, Vanderstraeten GG, Cambier DC, Witvrouw EE, De Cuyper HJ, Danneels L. CT imaging of trunk muscles in chronic low back pain patients and healthy control subjects. Eur Spine J. 2000;9(4):266–272. doi: 10.1007/s005860000190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hides J, Gilmore C, Stanton W, Bohlscheid E. Multifidus size and symmetry among chronic LBP and healthy asymptomatic subjects. Man Ther. 2008;13(1):43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2006.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamaz M, Kiresi D, Oguz H, Emlik D, Levendoglu F. CT measurement of trunk muscle areas in patients with chronic low back pain. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2007;13(3):144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parkkola R, Rytökoski U, Kormano M. Magnetic resonance imaging of the discs and trunk muscles in patients with chronic low back pain and healthy control subjects. Spine. 1993;18(7):830–836. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199306000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gildea JE, Hides JA, Hodges PW. Size and symmetry of trunk muscles in ballet dancers with and without low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013;43(8):525–533. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2013.4523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teichtahl AJ, Urquhart DM, Wang Y, et al. Fat infiltration of paraspinal muscles is associated with low back pain, disability, and structural abnormalities in community-based adults. Spine J. 2015;15(7):1593–1601. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2015.03.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mengiardi B, Schmid MR, Boos N, et al. Fat content of lumbar paraspinal muscles in patients with chronic low back pain and in asymptomatic volunteers: quantification with MR spectroscopy. Radiology. 2006;240(3):786–792. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2403050820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kjaer P, Bendix T, Sorensen JS, Korsholm L, Leboeuf-Yde C. Are MRI-defined fat infiltrations in the multifidus muscles associated with low back pain? BMC Med. 2007;5(2). doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-5-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang S, Xu Y, Han X, Wu W, Tang Y, Wang C. Functional and morphological changes in the deep lumbar multifidus using electromyography and ultrasound. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):6539. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24550-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sweeney N, O’Sullivan C, Kelly G. Multifidus muscle size and percentage thickness changes among patients with unilateral chronic low back pain (CLBP) and healthy controls in prone and standing. Man Ther. 2014;19(5):433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2014.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiesel KB, Underwood FB, Mattacola CG, Nitz AJ, Malone TR. A comparison of select trunk muscle thickness change between subjects with low back pain classified in the treatment-based classification system and asymptomatic controls. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007;37(10):596–607. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2007.2574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paalanne N, Niinimaki J, Karppinen J, et al. Assessment of association between low back pain and paraspinal muscle atrophy using opposed-phase magnetic resonance imaging: a population-based study among young adults. Spine. 2011;36(23):1961–1968. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181fef890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hides JA, Stokes MJ, Saide M, Jull GA, Cooper DH. Evidence of lumbar multifidus muscle wasting ipsilateral to symptoms in patients with acute/subacute low back pain. Spine. 1994;19(2):165–172. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199401001-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berglund L, Aasa B, Michaelson P, Aasa U. Effects of low-load motor control exercises and a high-load lifting exercise on lumbar multifidus thickness: a randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2017;42(15):E876–E882. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung S, Lee J, Yoon J. Effects of stabilization exercise using a ball on multifidus cross-sectional area in patients with chronic low back pain. J Sports Sci Med. 2013;12(3):533. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sipaviciene S, Kliziene I, Pozeriene J, Zaicenkoviene K. Effects of a twelve-week program of lumbar-stabilization exercises on multifidus muscles, isokinetic peak torque and pain for women with chronic low back pain. J Pain Relief. 2017;07(01):01. doi: 10.4172/2167-0846.1000309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang Q, Li D, Yokotsuka N, et al. The intervention effects of different treatment for chronic low back pain as assessed by the cross-sectional area of the multifidus muscle. J Phys Ther Sci. 2013;25(7):811–813. doi: 10.1589/jpts.25.811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang Q, Li D, Zhang J, Yang D, Huo M, Maruyama H. Comparison of the efficacy of different long-term interventions on chronic low back pain using the cross-sectional area of the multifidus muscle and the thickness of the transversus abdominis muscle as evaluation indicators. J Phys Ther Sci. 2014;26(12):1851–1854. doi: 10.1589/jpts.26.1851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hosseinifar M, Akbari M, Behtash H, Amiri M, Sarrafzadeh J. The effects of stabilization and McKenzie exercises on transverse abdominis and multifidus muscle thickness, pain, and disability: a randomized controlled trial in nonspecific chronic low back pain. J Phys Ther Sci. 2013;25(12):1541–1545. doi: 10.1589/jpts.25.1541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akbari A, Khorashadizadeh S, Abdi G. The effect of motor control exercise versus general exercise on lumbar local stabilizing muscles thickness: randomized controlled trial of patients with chronic low back pain. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2008;21(2):105–112. doi: 10.3233/BMR-2008-21206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Danneels L, Vanderstraeten G, Cambier D, et al. Effects of three different training modalities on the cross sectional area of the lumbar multifidus muscle in patients with chronic low back pain. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35(3):186–191. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.35.3.186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saragiotto BT, Maher CG, Yamato TP, et al. Motor control exercise for nonspecific low back pain: a Cochrane review. Spine. 2016;41(16):1284–1295. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; Group atP. Preferred Reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med. 2012;22(3):276–282. doi: 10.11613/BM.2012.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong AY, Parent EC, Kawchuk GN. Reliability of 2 ultrasonic imaging analysis methods in quantifying lumbar multifidus thickness. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013;43(4):251–262. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2013.4478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahdavie E, Rezasoltani A, Simorgh L. The comparison of the lumbar multifidus muscles function between gymnastic athletes with sway-back posture and normal posture. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2017;12(4):607. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hodges P, Pengel L, Herbert R, Gandevia S. Measurement of muscle contraction with ultrasound imaging. Muscle Nerve. 2003;27(6):682–692. doi: 10.1002/mus.10375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dupont AC, Sauerbrei EE, Fenton PV, Shragge PC, Loeb GE, Richmond FJ. Real-time sonography to estimate muscle thickness: comparison with MRI and CT. J Clin Ultrasound. 2001;29(4):230–236. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ikezoe T, Asakawa Y, Fukumoto Y, Tsukagoshi R, Ichihashi N. Associations of muscle stiffness and thickness with muscle strength and muscle power in elderly women. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2012;12(1):86–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00735.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Higgins JP, Sterne JA, Savovic J, et al. A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10(Suppl 1):29–31. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murad MH, Mustafa RA, Schünemann HJ, Sultan S, Santesso N. Rating the certainty in evidence in the absence of a single estimate of effect. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2017;22(3):85–87. doi: 10.1136/ebmed-2017-110668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. John Wiley & Sons; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ostelo RW, de Vet HC. Clinically important outcomes in low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2005;19(4):593–607. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2005.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson A, Hides JA, Blizzard L, et al. Measuring ultrasound images of abdominal and lumbar multifidus muscles in older adults: a reliability study. Man Ther. 2016;23:114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2016.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hides JA, Richardson CA, Jull GA. Multifidus muscle recovery is not automatic after resolution of acute, first-episode low back pain. Spine. 1996;21(23):2763–2769. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199612010-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akodu A, Akinbo S, Odebiyi D. Effect of stabilization exercise on lumbar multifidus muscle thickness in patients with non-specific chronic low back pain. Iran Rehabil J. 2014;12(2):6–10. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim G-Y, Kim S-H. Effects of push-ups plus sling exercise on muscle activation and cross-sectional area of the multifidus muscle in patients with low back pain. J Phys Ther Sci. 2013;25(12):1575–1578. doi: 10.1589/jpts.25.1575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee W, Lee Y, Gong W. The effect of lumbar strengthening exercise on pain and the cross-sectional area change of lumbar muscles. J Phys Ther Sci. 2011;23(2):209–212. doi: 10.1589/jpts.23.209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tagliaferri SD, Miller CT, Ford JJ, et al. Randomized trial of general strength and conditioning versus motor control and manual therapy for chronic low back pain on physical and self-report outcomes. J Clin Med. 2020;9(6):1726. doi: 10.3390/jcm9061726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wallwork TL, Stanton WR, Freke M, Hides JA. The effect of chronic low back pain on size and contraction of the lumbar multifidus muscle. Man Ther. 2009;14(5):496–500. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2008.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haefeli M, Elfering A. Pain assessment. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(Suppl 1):S17–S24. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-1044-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sokunbi Oluwaleke WP, Moore A. A randomised controlled trial (RCT) on the effects of frequency of application of spinal stabilisation exercises on multifidus cross sectional area (MFCSA) in participants with chronic low back pain. Physiother Singapore. 2008;11(2):9–16. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Staron R, Karapondo D, Kraemer W, et al. Skeletal muscle adaptations during early phase of heavy-resistance training in men and women. J Appl Physiol. 1994;76(3):1247–1255. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.3.1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mangine GT, Hoffman JR, Gonzalez AM, et al. The effect of training volume and intensity on improvements in muscular strength and size in resistance-trained men. Physiol Rep. 2015;3(8):e12472. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith BE, Littlewood C, May S. An update of stabilisation exercises for low back pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15(1):416. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gomes-Neto M, Lopes JM, Conceicao CS, et al. Stabilization exercise compared to general exercises or manual therapy for the management of low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther Sport. 2017;23:136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2016.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wong AY, Parent EC, Funabashi M, Kawchuk GN. Do changes in transversus abdominis and lumbar multifidus during conservative treatment explain changes in clinical outcomes related to nonspecific low back pain? A systematic review. J Pain. 2014;15(4):377 e371–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wong AY, Parent EC, Dhillon SS, Prasad N, Kawchuk GN. Do participants with low back pain who respond to spinal manipulative therapy differ biomechanically from nonresponders, untreated controls or asymptomatic controls? Spine. 2015;40(17):1329–1337. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sribastav SS, Peiheng H, Jun L, et al. Interplay among pain intensity, sleep disturbance and emotion in patients with non-specific low back pain. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3282. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wertli MM, Burgstaller JM, Weiser S, Steurer J, Kofmehl R, Held U. Influence of catastrophizing on treatment outcome in patients with nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review. Spine. 2014;39(3):263–273. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Werneke MW, Hart DL, George SZ, Stratford PW, Matheson JW, Reyes A. Clinical outcomes for patients classified by fear-avoidance beliefs and centralization phenomenon. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(5):768–777. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sions JM, Velasco TO, Teyhen DS, Hicks GE. Ultrasound imaging: intraexaminer and interexaminer reliability for multifidus muscle thickness assessment in adults aged 60 to 85 years versus younger adults. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014;44(6):425–434. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2014.4584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]