Abstract

Objective:

To identify which dental and/or cephalometric variables were predictors of postretention mandibular dental arch stability in patients who underwent treatment with transpalatal arch and lip bumper during mixed dentition followed by full fixed appliances in the permanent dentition.

Materials and Methods:

Thirty-one patients were divided into stable and relapse groups based on the postretention presence or absence of relapse. Intercuspid, interpremolar, and intermolar widths; arch length and perimeter; crowding; and lower incisor proclination were evaluated before treatment (T0), after lip bumper treatment (T1), after fixed appliance treatment (T2), and a minimum of 3 years after removal of the full fixed appliance (T3). Logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate the effect of changes between T0 and T1, as predictive variables, on the occurrence of relapse at T3.

Results:

The model explained 53.5 % of the variance in treatment stability and correctly classified 80.6 % of the sample. Of the seven prediction variables, intermolar and interpremolar changes between T0 and T1 (P = .024 and P = .034, respectively) were statistically significant. For every millimeter of increase in intermolar and interpremolar widths there was a 1.52 and 2.70 times increase, respectively, in the odds of having stability. There was also weak evidence for the effect of sex (P = .047).

Conclusions:

The best predictors of an average 4-year postretention mandibular dental arch stability after treatment with a lip bumper followed by full fixed appliances were intermolar and interpremolar width increases during lip bumper therapy. The amount of relapse in this crowding could be considered clinically irrelevant.

Keywords: Cephalometry, Dental arch, Malocclusion, Lip bumper, Relapse and mixed dentition

INTRODUCTION

Crowding due to tooth size/arch length deficiency is the most common form of malocclusion. Depending on facial balance and amount of crowding, there are two basic treatment approaches to address this clinical problem: extraction or nonextraction.1

Lip bumper is a nonextraction approach used to reduce dental arch crowding2,3 through an increase in arch width and length2–5 by altering the force equilibrium surrounding the dentition (lips, cheeks, and tongue).6,7 The main lip bumper effects, such as significant increases in deciduous or permanent intercanine,2,3 deciduous intermolar,2 premolar,4,8 and intermolar width,8 arch perimeter, and arch length2 are well-known and have been reported in the literature.5

Posttreatment dental arch instability is one of the main disadvantages of nonextraction treatment approaches,9–11 nevertheless, the postretention stability of these changes remains controversial and barely explored.

Ferris et al.12 assessed long-term stability after an average of 7.9 years with rapid palatal expansion and lip bumper therapy followed by full fixed appliances. They reported that mandibular crowding decreased during treatment by 1.03 mm but increased by 1.81 mm at follow-up.

Solomon et al.13 evaluated, after an average of 8.6 years, changes in patients treated with a lip bumper. They reported a decrease in irregularity of 3.73 mm during treatment and a posttreatment increase of 0.76 mm.

Finally, Raucci et al.14 evaluated short- and long-term mandibular arch changes in patients treated with a transpalatal arch and a lip bumper followed by full fixed appliances. They reported a decrease in lower arch crowding by 5.39 mm at the end of treatment, which remained relatively stable after an average of 6.3 years. Nevertheless, there was an increase of 0.36 mm resulting in minor relapse in some patients. However, occlusal and cephalometric differences between patients showing stability and those having relapse were not investigated.

Therefore, the aim of this retrospective study was to identify which dental and/or cephalometric variables were predictors of postretention mandibular dental arch stability in patients who underwent treatment with transpalatal arch and lip bumper during mixed dentition followed by full fixed appliances in the permanent dentition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Appropriate ethical approval was secured from the Health Research Ethics Board of the Second University of Naples (0003573/2015; February 2015).

Dental casts and lateral cephalograms of 31 consecutively treated patients (12 boys and 19 girls) gathered from a private orthodontic practice in Naples, Italy, were considered. This same sample was previously reported14 while answering a different clinical question.

Included patients ‘characteristics were as follows:

– Class I or II malocclusion

– Mild to moderate mandibular dental arch crowding (<6 mm)15

– Mixed dentition

– Younger than 9 years of age at T0

– Cervical vertebral maturation16 of one or two before treatment start.

None of the included patients had undergone previous orthodontic treatment, had craniofacial anomalies or required an extraction treatment.

Available records for the treated group included data from before lip bumper treatment (T0), after lip bumper treatment (T1), after full fixed appliances (T2), and a minimum of 3 years after fixed appliances, with an average follow-up of 6.3 years (T3). Treated patients were divided into stable and relapse groups based on the postretention presence or absence of relapse (no crowding or >0.1 mm of total crowding) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of the Treated Patients

| Group |

Number |

Average Age (y/mo) |

|||||

| Total |

Male |

Female |

T0 |

T1 |

T2 |

T3 |

|

| Stable | 16 | 4 | 12 | 9.19 ± 1.57 | 11.256 ± 1.13 | 13.58 ± 1.29 | 19.56 ± 2.66 |

| Relapse | 15 | 8 | 7 | 8.89 ± 1.75 | 10.94 ± 1.88 | 13.25 ± 2.14 | 19.99 ± 2.08 |

| Total | 31 | 12 | 19 | 9.04 ± 1.63 | 11.1 ± 1.52 | 13.42 ± 1.73 | 19.7 ± 2.37 |

Table 1.

Extended

| Crowding (mm) of Lower Arch |

Duration of Postretention Period |

|||

| T0 |

T1 |

T2 |

T3 |

|

| −4.81 ± 2.31 | −0.62 ± 1.53 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.92 ± 2.84 |

| −6.02 ± 3.03 | −1.53 ± 1.24 | 0.00 | −0.75 ± 0.26 | 6.67 ± 3.14 |

| −5.4 ± 2.71 | −1.1 ± 1.45 | 0.00 | −0.36 ± 0.42 | |

Treatment Protocol

Evaluation included three phases. During the first phase (T0-T1), which lasted about 2 years and occurred in mixed dentition, a lip bumper was used; a 0.045-inch, round, stainless steel wire (American Orthodontics, Sheboygan, Wis) with U-loops mesial to the first permanent molars was positioned at the gingival level 2 mm buccal to the teeth, inserted passively into the molar tubes, and then activated 1.5 mm every 40 days. During the second phase (T1-T2), which lasted about 2 years and occurred in permanent dentition, a standard edgewise fixed appliance (0.022-inch slot) was used to detail the occlusion in Class I relationship. The third phase (T2-T3) was the follow-up evaluation, which took place at least 3 years after the end of active treatment (overall mean = 6.3 ± 2.96 years; mean = 5.92 ± 2.84 and 6.67 ± 3.14 for stable and relapse groups, respectively). This phase also included a retention period with a fixed canine-to-canine retainer that lasted at least 2 years, so the postretention period, without any retainers, was 4 years on average.

Measurements

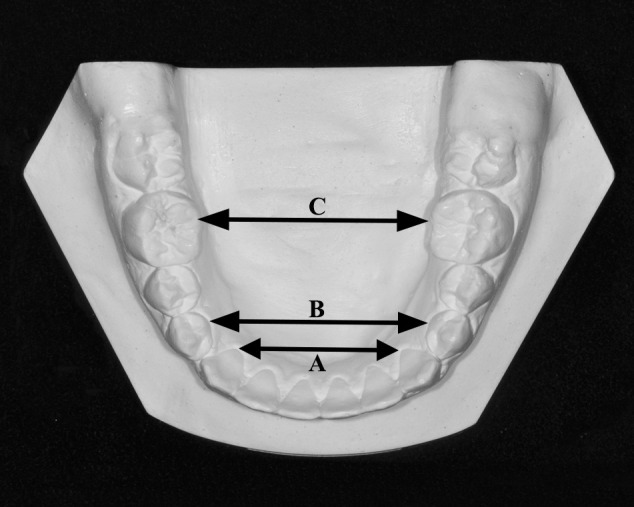

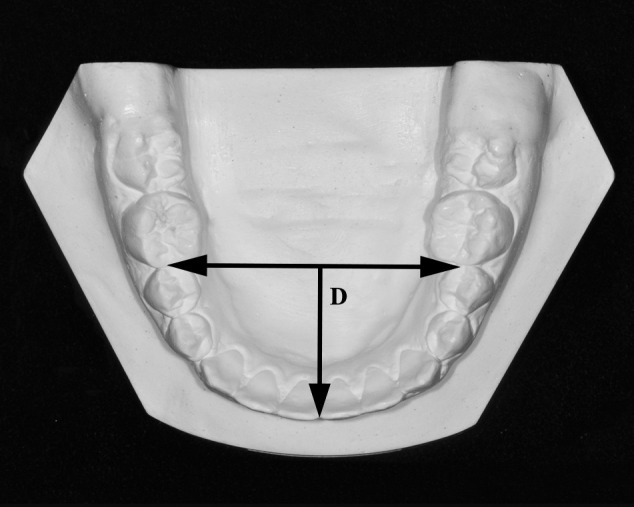

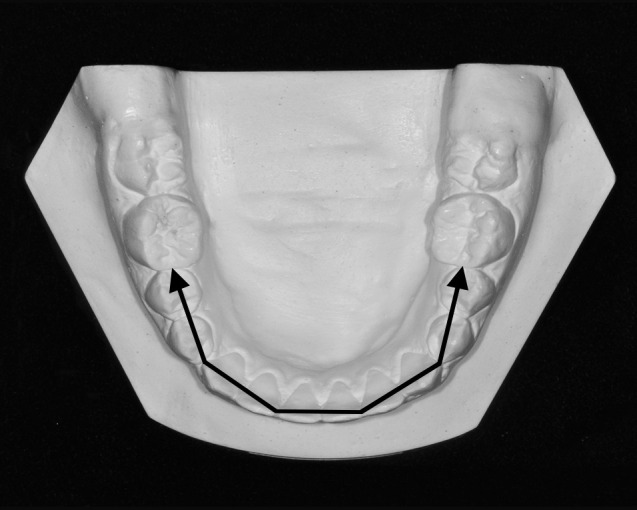

For dental cast analysis a black 2H pencil with a 0.5-mm tip was used to mark the anatomic landmarks at four time periods (Figure 1), and measurements were completed with digital calipers (0–150 mm). The inner lingual points on the gingival margin of the deciduous or permanent canines and first deciduous molars or premolars were taken to calculate the intercanine and the interpremolar widths (Figure 2).17 The point of intersection of the lingual groove with the cervical gingival margin at the first molars was taken to calculate the intermolar width (Figure 2).18 The perpendicular distance from the most facial point on the most prominent central incisor to a line constructed between contact points mesial to the permanent first molars was taken to calculate the arch length (Figure 3).17 Points on the mesial aspect of the permanent first molars, on the distal side of the canines and central incisors were taken to calculate arch perimeter (Figure 4).17 Unerupted teeth were represented by a point halfway between the adjacent permanent teeth centered buccolingually on the alveolar process. Crowding was measured as the tooth-size/arch-length discrepancy. Once marked, the occlusal surface of each dental cast was photocopied. For each patient, copies were made in sets of four mandibular arches. For the cephalometric analysis, only IMPA angle19 was considered between the long axis of the most prominent incisor and the mandibular plane (Go-Gn).

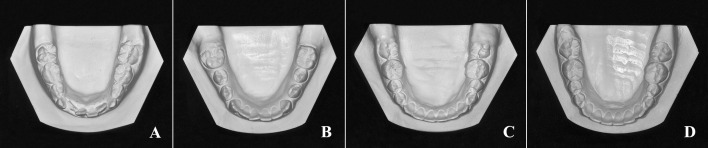

Figure 1.

Lower dental casts at the four time periods. (A) Before treatment. (B) After lip bumper. (C) After fixed appliances. (D) Follow-up.

Figure 2.

Arch width measurements. (A) Intercanine width. (B) Interpremolar width. (C) Intermolar width.

Figure 3.

Arch length measurement (D).

Figure 4.

Arch perimeter measurement.

Statistical Analysis

Data analyses were done using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 23; SPSS, Chicago, III). Means and standard deviations (SDs) were used to describe continuous variables, while frequencies were used for presenting categorical variables. The dental casts and lateral cephalometric were measured twice with a 1-week interval. The interreliability (consistency) of evaluators while measuring dental casts was determined via intraclass correlation (ICC). The measurement error for lateral cephalometric, based on the IMPA angle, was calculated using Dahlberg's formula. Logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate the effect of changes between T0 and T1, as predictive variables, on the occurrence of relapse at T3. A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

In total, 31 treated patients were included. Excellent interreliability (consistency) was demonstrated through an average ICC = 0.99 (95% confidence interval = 0.97, 0.99) while measuring dental casts. The Dahlberg formula calculated the standard error for the cephalometric analysis (IMPA) to be 0.04° for the treatment group. These values are considered very weak statistically and not considered clinically significant.

Changes in key measurements occurred between T0 and T1 for both treated groups and are presented in Table 2. A logistic regression was carried out to determine the impact of mandibular arch widths, length, and perimeter, as well as lower incisor inclination and crowding changes, between T0 and T1 on the likelihood that participants have postretention stable orthodontic treatment results.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations (SDs) of Changes in Measure That Occurred Between T0 and T1 Among Both Treated Groups

| Stability |

N |

Mean |

SD |

Standard Error |

| Intercanine | ||||

| Stable | 16 | 1.42 | 1.22 | 0.30 |

| Relapse | 15 | 1.91 | 1.35 | 0.34 |

| Interpremolar | ||||

| Stable | 16 | 2.41 | 1.57 | 0.39 |

| Relapse | 15 | 3.37 | 1.68 | 0.43 |

| Crowding | ||||

| Stable | 16 | 4.18 | 2.35 | 0.58 |

| Relapse | 15 | 4.50 | 2.53 | 0.65 |

| Arch length | ||||

| Stable | 16 | –0.73 | 1.59 | 0.39 |

| Relapse | 15 | –0.36 | 1.13 | 0.29 |

| Perimeter | ||||

| Stable | 16 | 3.12 | 5.13 | 1.28 |

| Relapse | 15 | 2.54 | 3.92 | 1.01 |

| Intermolar | ||||

| Stable | 16 | 3.66 | 2.63 | 0.65 |

| Relapse | 15 | 2.34 | 1.99 | 0.51 |

| IMPA | ||||

| Stable | 16 | –0.28 | 4.22 | 1.05 |

| Relapse | 15 | 1.96 | 2.89 | 0.74 |

The final model explained 53.5% (Nagelkerke r2) of the variance in treatment stability and correctly classified 80.6% of the sample. Of the seven prediction variables, intermolar and interpremolar changes (P = .024 and P = .034, respectively) were statistically significant (Table 3). For every millimeter of increase in intermolar and interpremolar widths at T1 (after lip bumper treatment and before starting the fixed orthodontic treatment) the odds of having stability increased 1.52 and 2.70 times, respectively. There was also a weak evidence for the effect of sex (P = .047).

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Model Predicting Likelihood of the Stability of the Orthodontic Treatment Based on Changes That Occurred between T0 and T1

|

B

|

Standard Error |

Wald |

df

|

P*

|

Odds Ratio |

95% Confidence Interval for Odds Ratio |

||

| Lower |

Upper |

|||||||

| Intercuspid width | 0.313 | 0.466 | 0.451 | 1 | .502 | 1.367 | 0.549 | 3.406 |

| Interpremolar width | 0.996 | 0.471 | 4.470 | 1 | .034* | 2.707 | 1.075 | 6.815 |

| Intermolar width | 0.648 | 0.286 | 5.122 | 1 | .024* | 1.523 | 1.298 | 1.917 |

| Crowding | 0.311 | 0.496 | 0.394 | 1 | .530 | 1.365 | 0.517 | 3.607 |

| Arch length | 0.006 | 0.114 | 0.003 | 1 | .959 | 1.006 | 0.804 | 1.258 |

| Arch perimeter | –0.165 | 0.258 | 0.408 | 1 | .523 | 0.848 | 0.512 | 1.405 |

| IMPA | 0.196 | 0.125 | 2.475 | 1 | .116 | 1.216 | 0.196 | 0.125 |

| Sex | 2.742 | 1.380 | 3.951 | 1 | .047* | 1.523 | 0.079 | 3.195 |

| Constant | –1.607 | 1.346 | 1.426 | 1 | .232 | 0.200 | ||

P< .05; df indicates degrees of freedom

DISCUSSION

The results of this study increase our understanding of mandibular dental arch dimensional changes and their postretention stability among growing patients treated with a lip bumper followed by fixed appliances.

The initial treatment response was elimination of the crowding identified at T014 but, as expected, complete stability is unrealistic. By splitting cases that demonstrated stability vs those that were unstable the study goal was to determine which quantified changes between T0 and T1 could predict the attained stability in a clinically meaningful manner. In this regard, intermolar and interpremolar width changes that occurred between T0 and T1 were predictive.

The odds of postretention stability (around 4 years after retention) increased by 1.52 and 2.7, respectively for every millimeter by which intermolar and interpremolar width expanded during lip bumper treatment. We hypothesize that the attained width correction with the use of the lip bumper between T0 and T1 could have been produced by physiological and not by active mechanical expansion, so this limited the amount of relapse. It has been previously suggested that it is important to work with and not against the soft tissue equilibrium (cheek, lip, and tongue pressures).7,20

It is interesting to note how the initial amount of crowding was not a predictive variable. This could be attributed at least partially to the fact that a goal of lip bumper treatment is not to eliminate all the crowding but to passively generate space that could be used later to relieve crowding partially or totally. In addition, the lip bumper was used for a set amount of time as per a specific protocol not based on the amount of crowding.

There was also weak evidence for the effect of gender on relapse (P = .047). This finding is puzzling, as there does not seem to be a logical explanation for the effect of gender on relapse tendencies. The fact that females complete craniofacial growth earlier than males may explain an apparent increased stability for females. The difference is almost nonstatistically significant.

The observed stability may also be the result, at least partially, of a good final intercuspation in Class I relationship. But it has to be noted that in some cases, relapse occurred even with good intercuspation. This variable was not considered in this study.

Although in this sample 15 patients (48%) showed relapse after an average 6.3-year follow-up, the amount could be considered clinically irrelevant. A closer look shows that in this sample, a high percentage of the intercanine (92%), interpremolar (96%), and intermolar (94%) width increases were maintained after the follow-up period. A slight tendency toward relapse was detected with a small amount (0.37 mm), but regardless, 5.4 mm of the initial crowding remained resolved.14 This can clearly be considered clinically successful.

When considering the available literature, a direct comparison of the results with other studies is difficult because postretention dental arch changes in patients treated with a lip bumper in mixed dentition followed by full fixed appliances have rarely been documented. Moreover, any relatively similar available study was not comparable because of different appliances, sex, ages, ethnic background, treatment length, and method of analysis. Ferris et al.12 reported greater postretention decreases in intermolar, interpremolar, and intercanine widths of 1.5, 1.2, and 0.9 mm, respectively. Solomon et al.13 reported significant decreases of 1.2 mm for interpremolar width only, whereas intercanine and intermolar widths lost 0.4 and 0.6 mm, respectively. Both studies12,13 reported higher relapse than did ours,14 probably because of the greater active mechanical expansion achieved during the use of the fixed appliances.

Limitations

The average 6.3-year follow-up included a 2-year retention period. In addition, the term “crowding” is ambiguous15 and in this study was measured as the tooth-size/arch-length discrepancy.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of this study increase our understanding of postretention stability after treatment with transpalatal arch and lip bumper during mixed dentition followed by full fixed appliances in the permanent dentition.

The best predictors of stability were mandibular intermolar and interpremolar widths after an initial treatment phase with a lip bumper.

The odds of postretention stability (average of 4 years after retention discontinuation) increased by 1.52 and 2.7 times, respectively, for every millimeter by which intermolar and interpremolar width expanded during lip bumper treatment.

REFERENCES

- 1.Janson G, Araki J, Estelita S, Camardella LT. Stability of class II subdivision malocclusion treatment with 3 and 4 premolar extractions. Prog Orthod. 2014;15:67. doi: 10.1186/s40510-014-0067-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davidovitch M, McInnis D, Lindauer SJ. The effects of lip bumper therapy in the mixed dentition. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1997;111:52–58. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(97)70302-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferro F, Perillo L, Ferro A. Non extraction short-term arch changes. Prog Orthod. 2004;5:18–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moin K, Bishara SE. An evaluation of buccal shield treatment: a clinical and cephalometric study. Angle Orthod. 2007;77:57–63. doi: 10.2319/120405-423R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hashish DI, Mostafa YA. Effect of lip bumpers on mandibular arch dimensions. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;135:106–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Donnell S, Nanda RS, Ghosh J. Perioral forces and dental changes resulting from mandibular lip bumper treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998;113:247–255. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(98)70293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasler R, Ingervall B. The effect of a maxillary lip bumper on tooth position. Eur J Orthod. 2000;22:25–32. doi: 10.1093/ejo/22.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perillo L, Padricelli G, Isola G, Femiano F, Chiodini P, Matarese G. Class II malocclusion division 1: a new classification method by cephalometric analysis. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2012;13:192–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perillo L, Castaldo MI, Cannavale R, et al. Evaluation of long-term effects in patients treated with Fränkel-2 appliance. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2011;12:261–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Proffit WR. Equilibrium Theory visited: Factors influencing position of the teeth. Angle Orthod. 1978;48:175–186. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1978)048<0175:ETRFIP>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raucci G, Elyasi M, Pachêco-Pereira C, et al. Predictors of long-term stability of maxillary dental arch dimensions in patients treated with a transpalatal arch followed by fixed appliances. Prog Orthod. 2015;16:24. doi: 10.1186/s40510-015-0094-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferris T, Alexander RG, Boley J, Buschang PH. Long-term stability of combined rapid palatal expansion-lip bumper therapy followed by full fixed appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;128:310–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon MJ, English JD, Magness WB, McKee CJ. Long-term stability of lip bumper therapy followed by fixed appliance. Angle Orthod. 2006;76:36–42. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2006)076[0036:LSOLBT]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raucci G, Pachêco-Pereira C, Elyasi M, d'Apuzzo F, Flores-Mir C, Perillo L. Short- and long-term evaluation of mandibular dental arch dimensional changes in patients treated with a lip bumper during mixed dentition followed by fixed appliances. Angle Orthod. 2016. 86:753–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Little RM. The irregularity index: a quantitative score of mandibular anterior alignment. Am J Orthod. 1975;68:554–563. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(75)90086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baccetti T, Franchi L, McNamara JA., Jr The cervical vertebral maturation (CVM) method for the assessment of optimal treatment timing in dentofacial orthopaedics. Semin Orthod. 2005;11:119–129. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adkins MD, Nanda RS, Currier GF. Arch perimeter changes on rapid palatal expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1990;97:194–199. doi: 10.1016/S0889-5406(05)80051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDougall PD, McNamara JA, Jr, Dierkes MJ. Arch width development in class II patients treated with the Frankel appliance. Am J Orthod. 1982;82:10–22. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(82)90541-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tweed CH. The Frankfort-mandibular plane angle in orthodontic diagnosis, classification, treatment planning, and prognosis. Am J Orthod Oral Surg. 1946;32:175–230. doi: 10.1016/0096-6347(46)90001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kau CH, Kantarci A, Shaughnessy T, et al. Photobiomodulation accelerates orthodontic alignment in the early phase of treatment. Prog Orthod. 2013;14:30. doi: 10.1186/2196-1042-14-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]