Abstract

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) can contribute to the triple bottom line of economic, social and environmental performance in organizations. However, the relationship between CSR, employee health and well-being has not been frequently assessed despite an increased awareness that this relationship can contribute to sustainable workplaces. To identify studies addressing the relationship between CSR and employee health and well-being within the EuCIropean context, we conducted a systematic literature search using Web of Science and Medline. Of the 60 articles screened for inclusion, 16 were retained. The results suggest that the majority (n = 14) of the identified studies aimed to understand the impact of CSR strategies on employees’ job satisfaction. None of the studies investigated the relationship between internal CSR and physical health. There was no clarity in the measurement of either internal CSR or the extent to which it affected employee outcomes. There is a need for consensus on measurement of internal CSR and of the health and well-being-related outcomes. Public health and occupational health researchers should be part of the discussion on the potential role of CSR in physical and psychological health outcomes beyond job satisfaction.

Keywords: corporate social responsibility (CSR), internal stakeholders, health and well-being, Europe

INTRODUCTION

The literature on corporate social responsibility (CSR) has grown rapidly in recent years, but the definition of the concept continues to be a matter of debate (Peloza, 2009; Aguinis, 2011; European Commission, 2011). Nevertheless, there is substantial agreement that CSR refers to the responsibility of businesses towards their impact on society, the environment and different stakeholders (; Hart, 1997; Carroll, 1999; Shamir, 2005; European Commission, 2011; Tomaselli et al., 2018). In this article, we use the definition by Aguinis (Aguinis, 2011): CSR constitutes the ‘context-specific organizational actions and policies that take into account stakeholders’ expectations and the triple bottom line of economic, social, and environmental performance’. At its core, CSR is also a business ethics concern, with a view on corporate core values and culture aimed at promoting responsible behaviour. Although the concept of CSR may vary across contexts, organizations are commonly expected to direct their activities towards poverty reduction, environmental protection, improvement of public health and better education (Macassa et al., 2017).

CSR entails having social responsibility towards different stakeholders, both external and internal to the organization: externally in relation to the surrounding society and internally within the corporation (Macassa et al., 2017).

According to the stakeholder theory, business organizations are expected to engage with their stakeholders through various initiatives and activities (Donaldson and Preston, 1995; Barrena-Martínez et al., 2016). A stakeholder-oriented CSR approach emphasizes the role organizations exist within an environment of large networks of stakeholders, all of which might stake claim on the organization (Barrena-Martínez et al., 2016). Some argue that managers must know about entities in their environment that hold power and have the intent to impose their will upon the organization. Power and urgency must be attended to if managers are to serve the legal and moral interests of legitimate stakeholders (Donaldson and Preston, 1995; Mitchell et al., 1997).

External social responsibility extends towards the community and broader society, as well as environmental concerns, while internal responsibility is related to the business entity’s own workforce (Zwetsloot and Leka, 2008; Aguinis, 2011). Internal corporate responsibility covers practices and strategies to improve employees’ safety and health (Zwetsloot and Starren, 2004; Vives, 2006; Ali et al., 2010; Macassa et al., 2017), human rights (Al-bdour et al., 2010; DeConinck, 2010; Ellemers et al., 2011; Chun et al., 2013), training, equality of opportunities in business (Thang, 2012; Ayub et al., 2013; Wambui et al., 2013) and work–life balance (Zwetsloot and Starren, 2004; Özbilgin et al., 2011).

It has been suggested that internal CSR strategies and processes are directly linked to employee well-being, through job satisfaction indicators that assess what employees expect from their organizations (Al-bdour et al., 2010; Yousaf et al., 2016). Furthermore, current evidence suggests that employees expect their organizations to demonstrate social responsibility by guaranteeing recognition, rewards, personal development opportunities, work–life balance, empowerment, involvement in the organization and retirement benefits (Tamm et al., 2010; Zanko and Dawson, 2012). According to Bernard, business organizations are expected to invest in health and safety management practices that have an impact on the company performance (Bernard, 2012). It has been argued that a company’s safety working environment is important to employees in terms of job security, job performance and increasing job commitment. For instance, a study by Hải (Hải, 2012) revealed a positive relationship between organizational commitment and work environment.

Occupational health and safety (OHS) is a multidisciplinary concept that addresses the promotion of safety, health and welfare of people engaged in work or employment (Amponsah-Tawiah and Dartey-Baah, 2011; Bhagawati, 2015). It encapsulates the physical, emotional and mental well-being of the worker in relation to the conduct of their work and, as a result, marks an essential subject of interest, impacting positively on the achievement of organizational goals (Amponsah-Tawiah and Dartey-Baah, 2011; Zanko and Dawson, 2012).

Health and well-being influence each other mutually in the workplace. Research from different contexts shows that occupational stress affects employees’ well-being because of contrasts between employees’ individual needs and demands, as well as the work environment (Glavas, 2016). Cooper and Marshall point to six important factors that induce occupational stress: factors intrinsic to the job (e.g. work overload, shift work, long hours, travel risk and danger, new technology and quality of the work environment), factors related to one’s role in the organization (role ambiguity, role conflict and degree of responsibility for others), factors related to relationships at work (with subordinates, colleagues and superiors), factors related to career development and job insecurity, factors related to the organizational structure and climate (lack of participation and effective consultation, poor communication, politics and the consequences of downsizing) and factors related to the home/work interface (balance between private and work life) (Cooper and Marshall, 1978). Others argue that besides OHS, CSR also includes issues regarding employment and employment relations, in terms of employment and employment relationship and social dialogue (Sowden and Sinha, 2005). Employees expect organizations to guarantee rewards, recognition, personal development opportunities, work–life balance, OHS and retirement benefits (Sowden and Sinha, 2005; Aguinis and Glavas, 2012; Krainz, 2015), all of which are important for job satisfaction. For instance, a study conducted in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania found a positive relationship between CSR, job satisfaction and employee well-being (Tamm et al., 2010).

In recent years, some have argued for the need to view employee health and well-being beyond the physical work environment, as well as to consider physiological stress that can be experienced in the workplace (Gordon and Schnall, 2017). Gordon and Schnall point to the importance of adopting a public health approach to occupational health, thereby considering the significant contribution of the psychosocial environment in employee and organizational health and well-being (Gordon and Schnall, 2017). They explicate that workplaces do not reside in isolation and that employees are likely to experience both social and psychological conditions (psychosocial work environment) (Gordon and Schnall, 2017). The psychosocial work environment includes risks that arise from psychological perceptions of employees with the risks of the social environment (WHO, 2010, LaMontagne et al., 2014; Gordon and Schnall, 2017). The social environment encompasses the social and economic forces brought by global economic competition that may impact the way in which work could be unhealthy to the most disadvantaged and vulnerable groups in society. These groups often occupy the lowest socioeconomic positions (e.g. women and ethnic minorities), whose health status is already compromised (Gordon and Schnall, 2017).

The psychosocial environment is a very important predictor of employee health and well-being. It affects well-being from two viewpoints, namely the positive affective states such as happiness (hedonic) and functioning with optimal effectiveness, and the social life perspective (eudaimonic) (Ryan and Deci, 2001; Vivoll and Vittersø, 2012; Huta and Waterman, 2014; Bartels et al., 2019). Furthermore, the psychosocial work environment has a greater impact on health, health behaviours, effectiveness, performance and productivity of workers and organizations (Kompier, 2005; NIOSH, 2008; Gram Quist et al., 2013; ILO, 2016). Exposure to work stressors, especially chronic stress (distress), is likely to decrease employee’s performance negatively affecting their productivity and engagement (Dobson and Schnall, 2017; Gordon and Schnall, 2017). Prolonged periods of distress have been associated with diabetes, burnout, clinical depression (Ferrie et al., 2016), cardiovascular disease (Fishta and Backé, 2015), musculoskeletal disorders (Madsen et al., 2018; Nafeesa et al., 2018), sickness absence and presentism (Milner et al., 2015; Landsbergis et al., 2017) and mortality (Goh et al., 2015). Stress is the most identified pathway through which the psychosocial environment impacts health outcomes (Gordon and Schnall, 2017). Regarding the workplace, eustress (positive stress) can contribute to better employee engagement and productivity through heightened focus, attention, passion, increased job performance and for employees to engage better at work and be more productive through focused attention and passion, increased job performance as well as positive emotions (Jarinto, 2010).

Work-related stress has been measured using a variety of dimensions such as job requirements, work environment, qualitative job requirements, organization of working time and work process, influence and development potential on the job, compatibility of family and work requirements, social relationships in the workplace, communication culture in the organization, managerial structure and leadership style and the individual risk of employees and emotional demands in the work place (Rugulies et al., 2010; Virtanen et al., 2012; Stenfors et al., 2013; Finne et al., 2014; Honda et al., 2016). For instance, a study by Virtanen found that overwork was a predictor of depression (Virtanen et al., 2012). In Lunau et al.’s study, qualitative job requirements (measured as lower education) were associated with higher stress levels at work (Lunau et al., 2015). Furthermore, Framke and colleagues’ study found that both perceived and content-related emotional demands at work predicted a higher risk of long-term sickness of absence among Danish employees (Framke et al., 2019). In relation to psychosocial work environment, North and colleagues found that low levels of work demand, control and support were related with high rates of short and long spells of sickness absence in men and women (North et al., 1996). Also using the same data within the Whitehall study, Marmot and co-authors reported an inverse gradient of coronary heart disease incidence was attributed to differences in psychosocial work environment (Marmot et al., 1997).

Job satisfaction is an important component of health, safety and well-being in the workplace. It is considered to be an important determinant of individual well-being, but it also affects societal economic prosperity as it has an impact on work productivity and retirement (Nadinloyi et al., 2013; Mory et al., 2016; Yousaf et al., 2016; Omer, 2018). For instance, it has been suggested that dissatisfaction at work can increase turnover and absenteeism, leading to lethargy and reduced organizational commitment as well as negative mental health outcomes such as depression (Nadinloyi et al., 2013). Other studies have found positive associations between CSR, employment engagement and job satisfaction (Koskela, 2014; Krainz, 2015; Seivwright and Unsworth, 2016; Jones, 2018). The most-researched relationship, by far, is the one between CSR and employee satisfaction and commitment, particularly concerning external CSR (Al-bdour et al., 2010; Nadinloyi et al., 2013; Mory et al., 2016; Yousaf et al., 2016). However, regarding internal CSR, which is the target of this review, these relationships have primarily been studied through the lens of social exchange and social identity theories. It has been suggested that the social exchange theory relates to a social exchange process that can be viewed as both a content and an outcome of the process, divided into six types of resources: love, services, goods, money, information and status (Al-bdour et al., 2010). In an organizational context, the resource ‘love’ can be understood as the attention paid by the organization to the employees in terms of providing support, comfort, security and stability. ‘Services’ refers to activities which the company offers to employees, while ‘goods’ refers to products, materials and objects that can be provided by the company (Al-bdour et al., 2010; Mory et al., 2016). ‘Money’ covers both financial resources and symbolic gifts, and ‘status’ includes prestige, respect and recognition. Finally, ‘information’ refers to education, advice and instruction given by the company to its employees (Al-bdour et al., 2010). According to Tajfel and Turner, with regard to the theory of social identity, an individual’s positive self-concept is developed by feeling membership within a specific group or organization (Tajfel and Turner, 1986).

Work–life balance is the equilibrium between time at work and time outside work. It is important for employee productivity and engagement, and thus affects retention rates and organizational commitment (Özbilgin et al., 2011). For instance, Bernard suggests that employees’ commitment to organizations can influence retention of competent staff through programmes that establish work–life balance (e.g. family-friendly practices), thus reducing work–life conflicts that can affect the organization (Bernard, 2012). Other studies suggest that the quality of work–life balance is associated with job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Al-bdour et al., 2010; Valcour et al., 2011).

The relationship between CSR, employee health and well-being has not been frequently assessed, although there is an increased awareness that this relationship can contribute to sustainable workplaces. CSR can contribute to the triple bottom line of economic, social and environmental performance in organizations, as well as employee health and well-being. The present article therefore aims to systematically review studies addressing the relationship between CSR and internal stakeholders’ (employees’) health and well-being in the European context. This review focuses solely on the extent to which internal CSR is directly linked to employee health and well-being (referred as internal stakeholders’ health and well-being).

METHODS

Search strategy

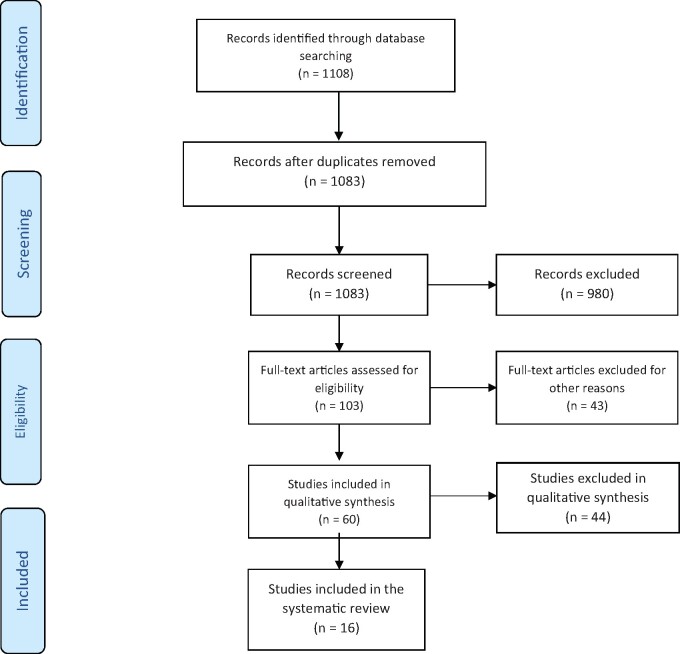

We conducted a systematic literature search using Web of Science and Medline. The search was facilitated by two trained librarians at a unit at Karolinska Institutet that offers professional search services. Both librarians have vast experience in systematic reviews. The review was conducted and reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Moher et al., 2009); a PRISMA flow chart is given in Figure 1. The review covered studies published from January 2001 to January 2019, in order to include studies carried out in the last decade after Carroll’s (Carroll, 1999) seminal paper on the evolution and definitional constructs of CSR.

Fig. 1:

Identification, screening, eligibility and inclusion of studies for the review.

Studies were included if they were published in full-text English language, were empirical studies conducted in Europe and addressed the relationship between CSR and internal stakeholders. Search terms included ‘CSR and occupational health and safety’, ‘CSR and employee health and well-being’, ‘CSR and job satisfaction’ and ‘CSR and work–life balance’. We excluded conference papers as well as conceptual, theory-building and review articles.

An additional and final search using the same databases and search terms was conducted by the team on 3 October 2019 to identify whether any new articles pertinent to this review were published between January and September 2019. None were identified.

Articles selection and assessment

A total of 1108 articles were identified in Web of Science and Medline. After duplicates were removed, 1083 articles remained to be thoroughly screened. All 1083 were retrieved and exported to EndNote and Mendeley for screening. Search limitations were applied in both EndNote and Mendeley to include the key words and concepts: corporate social responsibility, occupational health and safety, job satisfaction, health and well-being and work–life balance. This step generated a list of 103 articles which were then screened manually in two stages to remove irrelevant publications. The first stage was performed by C.M. and G.T., producing a total of 60 articles. In the second stage, the articles were further assessed by two pairs of authors (G.M. and G.T., and C.M. and S.C.B.). Disagreements in the inclusion and exclusion criteria were resolved within the research team based on the relevance of the articles to the research question. After excluding articles that included non-European countries along with European data, there were 16 articles complying with the inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

RESULTS

This section first presents the characteristics of the studies included in the review and then describes the findings of these studies.

Characteristics of the included studies

Sixteen studies published between 2007 and 2019 fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Three were conducted in Spain (Ruiz-Palomino et al., 2011; Celma et al., 2018; Pérez et al., 2018), two in the UK (Brammer et al., 2007; Raub and Blunschi, 2014), two in Belgium (De Roeck et al., 2014; Closon et al., 2015), two in Poland (Kowal and Roztocki, 2015; Zientara et al., 2015), two in Greece (Vlachos et al., 2013; Tsourvakas and Yfantidou, 2018) and one in each of Portugal (Gaudencio et al., 2017), Cyprus (Hadjimanolis and Boustras, 2013), Lithuania (Vveinhardt et al., 2017) and the Netherlands (Wisse et al., 2018). One study was carried out in more than one European country (Jain et al., 2011). Fifteen studies used a quantitative methodology, and one study used mixed methods including focus group interviews. The sample sizes varied from 43 (Jain et al., 2011) to 4712 respondents (Brammer et al., 2007) (see Table 1).

Table 1:

Studies included in the review (N = 16)

| Author(s) and year | Study | Country | Aim | Sample/ methods | Outcome | Summary of findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brammer et al. (2007) | The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment | UK | The paper examines the impact of three aspects of socially responsible behaviour on organizational commitment: employee perceptions of CSR in the community, procedural justice in the organization and the provision of employee training | (n = 4712) Survey | Job satisfaction | The results emphasize the importance of gender variation and suggest both that external CSR is positively related to organizational commitment and that the contribution of CSR to organizational commitment is at least as great as job satisfaction |

| Celma et al. (2018) | Socially responsible HR practices and their effects on employees' well-being: empirical evidence from Catalonia, Spain | Spain | The article empirically analyses the effectiveness of several practices of responsible human resource management, in relation to three well-known dimensions of employees' well-being at work: job stress, job satisfaction and trust in management | (n = 1647) Survey | Health and well-being | The results show that, in general, higher job quality increases employees' well-being at work, but some practices are more effective than others for each specific well-being dimension. The paper also suggests that some practices, such as job security and good environmental working conditions, seem to positively affect all domains of employees' well-being at work |

| Closon et al. (2015) | Perceptions of corporate social responsibility, organizational commitment and job satisfaction | Belgium | The paper aims to, investigate the impact of CSR's various dimensions on organizational commitment and job satisfaction, and to examine the moderating role of employee expectations in this relationship | (n = 621) Survey | Job satisfaction | The results show that ethical and legal internal and external practices significantly influence the affective organizational commitment. The results also indicate that job satisfaction is positively influenced by internal and external ethico-legal practices as well as by philanthropic practices |

| De Roeck et al. (2014) | Understanding employees' responses to corporate social responsibility: mediating roles of overall justice and organisational identification | Belgium | This study examines the impact of two aspects of an organization’s socially responsible behaviours, directed at internal and external stakeholders, on employees’ job satisfaction | (n = 181) Survey | Job satisfaction | The findings indicate that perceived CSR relates positively to job satisfaction through its effects on overall justice perceptions and organizational identification |

| Gaudencio et al. (2017) | The role of trust in corporate social responsibility and worker relationships | Portugal | The purpose of this paper is to show how organizational CSR can influence workers’ attitudes and behaviours, especially in terms of affective commitment (AC), job satisfaction (JS), and turnover intention (TI). A second aim is to explore the social exchange process that may underlie this relationship, by examining the mediating role of organizational trust (OT) | (n = 315) Survey (cross sectional) | Job satisfaction | The findings show that perceptions of CSR predict workers’ attitudes and behaviours directly through the mediating role of organizational trust. They suggest that managers should implement CSR practices because these can contribute towards fostering organizational trust, improving workers’ affective commitment and job satisfaction, and reducing turnover intention |

| Hadjimanolis and Boustras (2013) | Health and safety policies and work attitudes in Cypriot companies | Cyprus | The purpose of the paper is to investigate the association of organizational health and safety policies and procedures and safety perceptions of employees as reflected in safety climate with safety performance | (n = 272) Survey | Job satisfaction | Positive work attitudes have a positive impact on safety climate perceptions of the employees. A good safety climate contributes to improved safety performance. Safety policies have a direct impact on safety climate and safety performance. Safety policies increase job satisfaction and organizational commitment |

| Jain et al. (2011) | Corporate social responsibility and psychosocial risk management in Europe | Europe | This paper aims to explore the potential role of CSR in promoting well-being at work through the development of a framework for the management of psychosocial risks | (n = 43) EU15 members pre 2004, (n = 32) EU27, post 2004 members. Focus group interviews (n = 15) | Health and well-being | All stakeholders considered CSR to be an effective tool for improving social dialogue concerning psychosocial risk factors, with trade union representatives rating it as very useful, while government agency representatives and employer representatives considered |

| Kowal and Roztocki (2015) | Do organizational ethics improve IT job satisfaction in the Visegrád Group countries? Insides from Poland | Poland | To examine three dimensions of organizational ethics, ethical optimism, CSR and top management | 391 respondents | Job satisfaction | The study found that the three dimensions of organizational ethics, ethical optimism, CSR and top management action affected job satisfaction of information technology professionals |

| Pérez et al. (2018) | Sustainability in organizations: perceptions of CSR and Spanish employees attitudes and behaviours | Spain | To explore the relationship between perception of CSR company and employees behaviour and attitudes | 602 respondents | Job satisfaction | CSR three dimensions were positively and significantly related to job satisfaction and OCB behaviour |

| Raub and Blunschi (2014) | The power of meaningful work: how awareness of CSR initiatives foster task significance and positive work outcomes in services employees | UK | Test a model of the impact of employees’ awareness of CSR initiatives | 211 respondents | Job satisfaction | Employees awareness of CSR activities was positively related to job satisfaction and engagement |

| Ruiz-Palomino et al. (2011) | Employee organizational citizenship behaviour: the direct and indirect impact of ethical leadership | Spain | To examine supervisor ethical leadership (SEL), in banking and insurance companies to understand its relationship to employee job satisfaction, affective commitment and organizational citizenship behaviour | 525 respondents | Job satisfaction | SEL was directly and positively associated with both job satisfaction and affective commitment. The relationship between ethical leadership and employee organizational citizenship was mediated by job satisfaction and affective commitment |

| Tsourvakas and Yfantidou (2018) | Corporate social responsibility influences employee engagement | Greece | To explore the influence of CSR on employee engagement, motivation and job satisfaction on the staff members of two multinational companies | 154 respondents | Job satisfaction | Employees were proud to identify themselves with companies that had a caring image. CSR was positively linked to employee engagement |

| Vlachos et al. (2013) | Feeling good by doing good: employee CSR-induced attributions, job satisfaction, and the role of charismatic leadership | Greece | The study examined the impact of CSR initiatives on an important stakeholder group—employees | 438 respondents | Job satisfaction | Perceived charismatic leadership in managers was motive for engaging in CSR activities as well as job satisfaction. CSR-induced extrinsic attributions were not explained by charismatic leadership and did not predict job satisfaction |

| Vveinhardt et al. (2017) | Integrated actions for decrease and/or elimination of mobbing as a psychosocial stressor in the organizations accessing and implementing corporate social responsibility | Lithuania | The purpose of this research is, having examined the expression of mobbing as a psychosocial factor in organizations accessing or implementing CSR, to form integrated actions for the decrease and/or elimination of the phenomenon | 1512 respondents | Health and well-being | Comparing the organizations which declared and did not declare CSR, approval of the statements about psychosocial well-being was more significant in the latter ones, while in the organizations which declared CSR, orientation towards external interested subjects was revealed |

| Wisse et al. (2018) | Catering to the needs of an ageing workforce: the role of employee age in the relationship between corporate social responsibility and employee satisfaction | The Netherlands | To demonstrate that the effect of CSR on employee satisfaction will be more pronounced for older than for younger employees, because CSR practices address those emotional needs and goals that are prioritized when people’s future time perspective decreases | 643 respondents | Job satisfaction | CSR indeed has a stronger positive effect on employee satisfaction for older relative to younger employees. Accordingly, engaging in CSR can be an attractive tool for organizations that aim to keep their ageing workforce satisfied with their job |

| Zientara et al. (2015) | Corporate social responsibility and employee attitudes: evidence from a study of Polish hotel employees | Poland | This study tested a research model that investigated whether there were links between CSR, operationalized as ‘self-related’ CSR experiences and ‘others-related’ CSR experiences, and job satisfaction and organizational commitment, and between both attitudes and work engagement | 412 respondents | Job satisfaction | The results indicated that ‘others-related’ CSR experiences were positively associated with satisfaction and commitment, while ‘self-related’ CSR experiences with the latter variable. Likewise, organizational commitment, unlike job satisfaction, was linked to work engagement |

Relationship CSR and internal stakeholders’ health and well-being

The studies in the review addressed different dimensions of well-being in relation to CSR. All had a cross-sectional design. They used predominantly quantitative methodology, with one exception which used focus group interviews.

Celma et al. aimed to analyse the extent to which having a responsible human resources management within companies effectively helped to enhance employees’ well-being within the workplace (Celma et al., 2018). The authors conductedCI a survey among 1647 employees from Catalonia, Spain, focusing on three dimensions of employees’ well-being at work: job stress, job satisfaction and trust in management. The results showed that employees’ well-being levels were higher when job quality standards were also high. However, some practices were more effective than others in enhancing employees’ well-being, such as job security (including contract security) and a good and inclusive work environment.

Jain et al. aimed to explore the potential role of CSR in promoting well-being at work through the development of a framework for the management of psychosocial risks (Jain et al., 2011). The findings revealed that all stakeholders considered CSR to be an effective tool for improving social dialogue concerning psychosocial risk factors, with trade union representatives rating CSR higher than government agency representatives and employer representatives.

Vveinhardt et al. analysed data from companies that did and did not declare CSR (n = 772), finding that CSR helped to increase employees’ confidence and loyalty towards the organization among companies that declared CSR (Vveinhardt et al., 2017).

Drawing on social theory, Brammer et al. investigated gender differences in the relationship between organizational commitment and three aspects of CSR: employees’ perceptions of external CSR in the community, procedural justice in the organization and the provision of employee training (n = 4712) (Brammer et al., 2007). The results suggested that employees’ perceptions of CSR had a major impact on organizational commitment and that the contribution of CSR to organizational commitment was at least as great as that of job satisfaction. External CSR (strategies towards external stakeholders) was positively related to organizational commitment.

De Roeck et al. focused on the mechanisms that drove employees’ responses to CSR initiatives, specifically examining the impact on employees’ job satisfaction of two aspects of an organization’s socially responsible behaviour: employees’ perceptions of CSR initiatives directed at internal and external stakeholders, respectively (n = 181) (De Roeck et al., 2014). Also using social identity theory, the findings indicated that perceived CSR related positively to job satisfaction through the mediating effects of overall justice perceptions and organizational identification. These results also suggested that employees appeared to use CSR initiatives to assess their organization’s character and sense of belonging with it. Accordingly, CSR initiatives had particular importance as a means to support organizational efforts to create strong relationships with employees and thereby improve their attitudes at work.

Gaudencio et al. built on the importance of social exchange relationships to illustrate the role of organizational trust in CSR and suggested that managers should implement CSR practices because these could contribute towards fostering organizational trust, improving workers’ affective commitment and job satisfaction and reducing turnover intention (n = 315) (Gaudencio et al., 2017). The findings showed that perceptions of CSR predicted workers’ attitudes and behaviours directly through the mediating role of organizational trust.

Kowal and Roztocki used an internet survey (n = 391) to examine the relationship between organizational ethics and job satisfaction among IT professionals in Poland (Kowal and Roztocki, 2015). The findings suggested that organization ethics led to job satisfaction and that these professionals were more satisfied in companies where top management enforced high ethical standards. Conversely, the findings also suggested that the professionals were ethically pessimistic and that those who had a high belief in ethical standards were particularly unsatisfied with their jobs unless the workplace had a commitment towards organizational ethics.

Ruiz-Palomino et al. examined the direct and indirect impact of ethical leadership as a way of studying leadership–follower behaviour, using a survey of 525 banking and insurance employees in companies in Spain (Ruiz-Palomino et al., 2011). The findings suggested that manager’s ethical leadership and organizational citizenship were significantly and positively related to both job satisfaction and affective commitment to the organization.

Hadjimanolis and Boustras aimed to investigate the associations between employees’ work attitudes, employees’ safety perceptions (safety climate), employees’ safety performance and organizational health and safety policies and procedures in Cyprus (Hadjimanolis and Boustras, 2013). The results suggested that positive work attitudes had a positive impact on safety climate, that a good safety climate contributed to improved safety performance, that safety policies had a direct impact on safety climate and safety performance and that safety policies increased job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Tsourvakas and Yfantidou explored the influence of CSR on employees’ engagement, motivation and job satisfaction among staff members (n = 200) of two multinational companies operating in Greece (Tsourvakas and Yfantidou, 2018). The results indicated that employees were proud to identify themselves with companies that had a caring image and that CSR was positively linked to employees’ engagement and job satisfaction.

Wisse et al. (n = 143) found that age moderated the relationship between CSR and job satisfaction and that the relationship was stronger among older employees than among their younger counterparts (Wisse et al., 2018). The study also revealed differential effects of CSR practices on employees through the lifespan.

Vlachos et al. (n = 497) showed that when employees perceived their manager to be charismatic, they also attributed the organization’s CSR activities to intrinsically motivated values that in turn were positively associated with job satisfaction (Vlachos et al., 2013). Moreover, the study also found that CSR-induced extrinsic attributions were not explained by either charismatic leadership or job satisfaction.

Raub and Blunschi (n = 211) found that employees’ awareness of CSR activities was positively related to job satisfaction and engagement and negatively related to emotional exhaustion (Raub and Blunschi, 2014). The study also indicated that task significance was an important mediator in the relationship between awareness of CSR initiatives and discretionary work behaviour.

Pérez et al. (n = 602) analysed the relationship between perceptions of CSR and employees’ attitudes and behaviour (Pérez et al., 2018). The findings showed that all three dimensions of CSR were positively related to job satisfaction and to organizational citizenship behaviour oriented to the company and to co-workers. Although there were some differences between the CSR dimensions, they had similar importance. The study also revealed that sustainable economic development and environmental protection had a greater impact than social equity.

Closon et al. (n = 621) found that CSR in the form of ethical and legal internal and external practices had an impact on affective organizational commitment (Closon et al., 2015). The findings also indicated that ethico-legal and philanthropic practices positively influenced job satisfaction in the organization, viewed through the lens of citizen-worker interaction.

Finally, Zientara et al. studied low-ranking employees in Poland (n = 412) to analyse the link between ‘self-related’ and ‘others-related’ CSR experiences and job satisfaction, organizational commitment and work engagement (Zientara et al., 2015). Others-related CSR experiences were positively associated with job satisfaction and commitment, while self-related CSR experiences were associated only with commitment and not with job satisfaction.

DISCUSSION

Summary of results

The aim of this literature review was to identify and describe studies investigating the relationship between CSR and employees’ (internal stakeholders’) health and well-being, in the European context. The majority of the identified studies aimed to understand the impact of CSR strategies on employee job satisfaction; that is, the extent to which employees were satisfied with their work (Brammer et al., 2007; Ruiz-Palomino et al., 2011; Hadjimanolis and Boustras, 2013; Vlachos et al., 2013; De Roeck et al., 2014; Raub and Blunschi, 2014; Closon et al., 2015; Kowal and Roztocki, 2015; Zientara et al., 2015; Gaudencio et al., 2017; Vveinhardt et al., 2017; Pérez et al., 2018; Tsourvakas and Yfantidou, 2018; Wisse et al., 2018).

It has been argued that companies are increasingly interested in how internal CSR strategies can help them keep their current employees engaged and satisfied, attract new employees, keep and retain customers and above all advance their brand image (Mory et al., 2016; Yousaf et al., 2016). Others have pointed out that, as an outcome, job satisfaction gives an indication of the potential emotional state of employees concerning their job experience and work environment (Sarfraz et al., 2018). In this regard, job satisfaction can directly affect organizational performance and profitability (Yousaf et al., 2016; Abdallah et al., 2017).

It has also been suggested that business organizations can develop strategies that produce both intrinsic (moral values, creativity, achievement, power and independence) and extrinsic (work tasks and the work itself) job satisfaction (Abdallah et al., 2017). Others have argued that operational activities—that is, anything that an organization can carry out to improve its employees’ lives—can affect productivity, which in turn affects profitability (Pietersz, 2011; Nasrullah and Rahim, 2014). For instance, Kim et al. noted that employees are the ones who strategize and implement CSR, and hence that their attitudes and behaviours can determine the success or failure of an organization (Kim et al., 2018). Overall, internal CSR has been found to be associated with job satisfaction and three of its dimensions: work conditions, work–life balance and empowerment (Obeidat et al., 2018). According to Yousaf et al., working on attributes of social obligation and responsibility as part of the company’s human resources strategy is one of the most important, durable and effective way to keep the employees satisfied (Yousaf et al., 2016).

Regarding the connection between CSR and job satisfaction, various scholars have suggested that social identity theory and organizational identification mechanisms are the most used mechanistic pathways that explain individual reactions to CSR (Tajfel and Turner, 1986; Gond et al., 2017). Social identity theory postulates that people are likely to identify themselves with an organization that they perceive to be highly prestigious with an attractive and positive image. For instance, Gond et al. suggested that employees who had a positive image of the organization were more likely to remain within it (Gond et al., 2017). However, others have argued that there are flaws in the reliance on social identity theory as an explanatory mechanism in individual-related CSR studies, as very few studies actually test whether identification is the underlying mechanism that links CSR to employee outcomes such as job satisfaction (De Roeck et al., 2014; Farooq et al., 2014). Nevertheless, the present review included a study which used notions of the social identity theory to reveal a relationship between perceptions of CSR and organizational commitment (Brammer et al., 2007), which in turn has been found to be linked to employee job satisfaction, retention and performance (Meyer et al., 2002). The results of Brammer et al. also suggested that CSR had indirect benefits for internal stakeholders through organizational commitment, with women having stronger preferences for external CSR and procedural justice while men had stronger preference for the training provision (Brammer et al., 2007).

Only two studies in the present review directly attempted to address other outcomes concerning employee well-being that were not related to job satisfaction. For instance, one study Celma et al. found that CSR/human resource management practices had an impact on employees’ well-being, especially when job quality was perceived to be of a high standard (Celma et al., 2018).

Elsewhere, a conceptual study outside this review argues that the integration of CSR practices and human resources management might contribute to employee outcomes in terms of performance, motivation and commitment enhancement (Barrena-Martínez et al., 2019). Carried out in Spain the study suggested an array of socially responsible policies areas linked to human resources management (and occupational safety at work) practices such as retention and attraction of employees; fair remuneration and social benefits; prevention, health and safety at work; work–life balance; training and continuous development; management of employment relations; communication, transparency and social dialogue and diversity and equal opportunity (Barrena-Martínez et al., 2019).

Moreover, among the articles in the review, Jain et al. reported that employees perceived internal and external CSR as an effective tool to improve social dialogue with trade unions in relation to workplace psychosocial risk factors, which are known to be important for employee and workplace well-being (Jain et al., 2011).

The review revealed differences in how studies measured CSR, with some using internal CSR measures but others a mix of internal and external measures to investigate their impact on well-being (mostly measured by job satisfaction). At the micro-level, CSR has overwhelmingly addressed employee perceptions, attitudes and behaviours linked to job satisfaction; a well-being dimension that is known to directly impact organizational performance and profitability (Farooq et al., 2014). Furthermore, job satisfaction was measured using a variety of dimensions including employees’ organizational commitment and organizational citizenship, which to some extent made it difficult to align the findings of the review. Nevertheless, the majority of the review findings showed a direct and positive relationship between perceived CSR and job satisfaction in companies of different branches in several EU countries. Some studies measured job satisfaction and organizational commitment, which is the individual psychological attachment to an organization and willingness to make efforts for it (Kim et al., 2018). Organizational commitment is linked to absenteeism, citizenship behaviour, performance and turnover (Kim et al., 2018). Elsewhere, evidence has shown that although business organizations may recognize the importance of employees as stakeholders, less attention is paid to their labour standards, health and safety provisions as well as work–life balance (Cooke and He, 2010). Moreover, a study carried out in five countries (Australia, Germany, Japan, UK and USA) of which two are located in Europe found that differences between institutional regulations, corporate governance and cultural characteristics of national business systems explained variations in the size and significance of socially responsible investments across countries (Waring and Edwards, 2008). Furthermore, CSR may help business organizations in increasing their competitiveness and bringing benefits in terms of risk management, cost savings, access to capital, customer relationships, human resource management and innovation capacity (Iamandi, 2011; Iamandi and Constantin, 2012).

Strengths and limitations

The studies included in this review were carried out using a variety of sample sizes across different branches and in different countries. This fact, together with a lack of standardized methodology (measurement and analytical strategy), created challenges for any generalization of findings. Nonetheless, the review provides one of the first assessments of studies concerning associations between CSR and employees’ health and well-being in Europe. However, the review has its limitations. For instance, it did not include studies that were written in languages other than English, which could affect the findings, especially if they examined outcomes other than job satisfaction. In addition, we did not search the grey literature, as we were interested in research publications, but this could have led to our missing valuable insights. Finally, the search only included studies published up to September 2019; later literature may contain findings not addressed in this review.

Research gaps identified

The review identified several areas where future research should be concentrated. First, we did not find any study that directly related internal CSR and physical health. Attempts along these lines have been made elsewhere; for example, in the USA, Fairlie and Svergun investigated the relationship between CSR perceptions and stress symptoms (Fairlie and Svergun, 2015). The results revealed that there was a negative relationship and that CSR perceptions and stress symptoms appeared to have interrelated roles in predicting both negative stress-related outcomes and work engagement. Fairlie and Svergun also reported that CSR perceptions were positively associated with work satisfaction and appeared to buffer both depression symptoms and turnover intentions directly, through the mediation of job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Fairlie and Svergun, 2015). We argue that there is a need to carry out studies investigating the relation between internal CSR and physical and psychological health, as well as wellness in the workplace. Current discussions point to the importance of workplace wellness for employees’ health and well-being towards achieving sustainable and healthy workplaces (McCartney, 2015). There is a growing recognition that employers need to make employees’ mental health a priority in their CSR strategies, due to the ever-changing labour market that affects key dimensions of job quality and safety which contribute to increased psychosocial risks in the workplace (Baicker et al., 2010; Gołaszewska-Kaczan, 2015; Gubler et al., 2018). Moreover, some suggest that having a healthy organization (and healthy work) might be more expensive in a short-term (and in the context maximizing profits), the potential long-term consequences of employee mental well-being might be more grave due to costs to health care systems, family and society (Hassard et al., 2014; Gordon and Schnall, 2017). CSR presents a unique opportunity for business organizations to develop frameworks for management and possible reduction of psychosocial risks (through improvement of workplace psychosocial environment) at the employee and organizational levels (Jain et al., 2011; Sadlowska-Wrzesinska, 2017).

Second, it is important to improve the measurement of CSR, and in particular the internal dimension of CSR. This would allow a better comparison of studies from a variety of contexts in Europe as well as elsewhere.

Third, the majority of studies in the review were carried out by economic and management researchers, which highlights the need for health science researchers (e.g. public health and occupational health) to get involved in discussions surrounding the potential impact of internal CSR on employees’ physical and psychological health, as well as OHS outcomes beyond job satisfaction.

CONCLUSION

The aim of this work was to review studies that related CSR to employees’ (internal stakeholders’) health and well-being in the European context. The findings show that the majority of studies addressed the relation between CSR and job satisfaction. There was no clarity in the measurement of either internal CSR or the extent to which it affected employee outcomes. These results point to the need for a consensus on measurement of internal CSR and of outcomes related to health and well-being, in order to enable better comparison of findings from studies across Europe.

There is a need for public health and occupational researchers to join the discussion and research efforts regarding the potential role to be played by CSR in physical and psychological health outcomes other than job satisfaction. These outcomes are known to be linked with long-term business sustainability beyond just profitability. A better understanding of how CSR impacts employee health and well-being outcomes might be important to other type of organizations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Susanne Gustafsson and Sabina Gillsund from Karolinska Institutet University Library for performing the article searches. G.M. would additionally like to acknowledge the support of the Department of Public Health and Sports Science at the University of Gävle, through the RELeSH project.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

G.M. developed the concept and led the drafting of the manuscript; C.M. and G.T. performed the first article screening; G.M., G.T., C.M. and S.C.B. assessed the articles in the review; G.T. performed the extra article searches; G.M. and C.M. produced the first complete manuscript draft; G.M., C.M., G.T. and S.C.B. reviewed and commented on the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- Abdallah A. B., Obeidat B. Y., Aqqad N. O., Al Janini M. N. K., Dahiyat S. E. (2017) An integrated model of job involvement, job satisfaction and organizational commitment: a structural analysis in Jordan’s banking sector. Communications and Network, 09, 28–53. [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis H. (2011) Organizational responsibility: doing good and doing well. In Zedeck S. (ed), APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Chapter 24. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, pp. 855–879. [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis H., Glavas A. (2012) What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: a review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar]

- Al-bdour A. A., Nasruddin E., Lin S. K. (2010) The relationship between internal corporate social responsibility and organizational commitment within the banking sector in Jordan. International Journal of Human and Social Sciences, 5, 932–951. [Google Scholar]

- Ali I., Rehman K. U., Ali S. I., Yousaf J., Zia M. (2010) Corporate social responsibility influences, employee commitment and organizational performance. African Journal of Business Management, 4, 2796–2801. [Google Scholar]

- Amponsah-Tawiah K., Dartey-Baah K. (2011) Occupational health and safety: key issues and concerns in Ghana. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Ayub A., Iftekhar H., Aslam M. S., Razzaq A. (2013) A conceptual framework on examining the influence of behavioral training & development on CSR: an employees’ perspective approach. European Journal of Business and Social Sciences, 2, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Baicker K., Cutler D., Song Z. (2010) Workplace wellness programs can generate savings. Health Affairs, 29, 304–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrena-Martínez J., López-Fernández M., Romero-Fernández P. M. (2019) Towards a configuration of socially responsible human resource management policies and practices: findings from an academic consensus. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30, 2544–2580. [Google Scholar]

- Barrena-Martínez J. B., Fernández M. L., Fernández P. M. R. (2016) Corporate social responsibility: evolution through institutional and stakeholder perspectives. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 25, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels A. L., Peterson S. J., Reina C. S. (2019) Understanding well-being at work: development and validation of the eudaimonic workplace wellbeing scale. PLoS One, 14, e0215957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard B. (2012) Factors that determine academic staff retention and commitment in private tertiary institutions in Botswana: empirical review. Global Advanced Research Journal of Management and Business Studies, 1, 278–299. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagawati B. (2015) Basics of occupational safety and health. IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology, 9, 91–94. [Google Scholar]

- Brammer S., Millington A., Rayton B. (2007) The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll A. B. (1999) Corporate social responsibility: evolution of a definitional construct. Business & Society, 38, 268–292. [Google Scholar]

- Celma D., Martinez-Garcia E., Raya J. M. (2018) Socially responsible HR practices and their effects on employees’ wellbeing: empirical evidence from Catalonia, Spain. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 24, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Chun S. J., Shin Y., Choi N. J., Kim S. M. (2013) How does corporate ethics contribute to form financial performance? The mediating role of collective organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behaviour. Journal of Management, 39, 853–877. [Google Scholar]

- Closon C., Leys C., Hellemans C. (2015) Perceptions of corporate social responsibility, organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Management Research: Journal of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management, 13, 31–54. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke F. L., He Q. (2010) Corporate social responsibility and HRM in China: a study of textile and apparel enterprises. Asia Pacific Business Review, 16, 355–376. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C. L., Marshall J. (1978) Understanding Executive Stress. Macmillan, London. [Google Scholar]

- De Roeck K., Marique G., Stinglhamber F., Swaen V. (2014) Understanding employees’ responses to corporate social responsibility: mediating roles of overall justice and organisational identification. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25, 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- DeConinck J. B. (2010) The influence of ethical climate on marketing employees’ job attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Business Research, 63, 384–391. [Google Scholar]

- Dobson M., Schnall P. L. (2017) From stress to distress: the impact of work on mental health. In Schnall P., Dobson M., Rosskam E. (eds), Unhealthy Work: Causes, Consequences and Curves. Routledge, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson T., Preston L. (1995) The stakeholder theory of the corporation: concepts, evidence and implications. Academy of Management Review, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ellemers N., Kingma L., van de Burgt J., Barreto M. (2011) Corporate social responsibility as a source of organizational morality, employee commitment and satisfaction. Journal of Organizational Moral Psychology, 2, 97–124. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. (2011) A Renewed EU Strategy 2011-14 for Corporate Social Responsibility. European Commission, 25 October 2011. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52011DC0681 (last accessed 4 November 2019).

- Fairlie P., Svergun O. (2015) The Interrelated Roles of CSR and Stress in Predicting Employee Outcomes. Work, Stress, and Health 2015: Sustainable Work, Sustainable Health, Sustainable Organizations. Paper presented at the 11th International Conference on Stress and Health, May 6–9, 2015, Atlanta, GA.

- Farooq O., Payaud M., Merunka D., Valette-Florence P. (2014) The impact of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: exploring multiple mediation mechanisms. Journal of Business Ethics, 125, 563–580. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrie J. E., Virtanen M., Jokela M., Madsen I. E. H., Heikkilä K., Alfredsson L.. et al. (2016) Job insecurity and risk of diabetes: a meta-analysis of individual participant data. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 188, E447–E455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finne L. B., Christensen J. O., Knardahl S. (2014) Psychological and social work factors as predictors of mental distress: a prospective study. PLoS One, 9, e102514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishta A., Backé E. M. (2015) Psychosocial stress at work and cardiovascular diseases: an overview of systematic reviews. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 88, 997–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Framke E., Sørensen J. K., Nordentoft M., Johnsen N. F., Garde A. H., Pedersen J.. et al. (2019) Perceived and content-related emotional demands at work and risk of long-term sickness absence in the Danish workforce: a cohort study of 26 410 Danish employees. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 76, 895–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudencio P., Coelho A., Ribeiro N. (2017) The role of trust in corporate social responsibility and worker relationships. Journal of Management Development, 36, 478–492. [Google Scholar]

- Glavas A. (2016) Corporate social responsibility and employee engagement: enabling employees to employ more of their whole selves at work. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh J., Pfeffer J., Zenios S. A., Rajpal S. (2015) Workplace stressors and health outcomes: health policy for the workplace. Behavioral Science & Policy, 1, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Gołaszewska-Kaczan U. (2015) Actions for promoting work life-balance as an element of corporate social responsibility. Research Papers of the Wrocław University of Economics, 387, 54–65. [Google Scholar]

- Gond J.-P., El Akremi A., Swaen V., Babu N. (2017) The psychological microfoundations of corporate social responsibility: a person‐centric systematic review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38, 225–246. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D. R., Schnall P. L. (2017) Beyond the individual: connecting work environment and health. In Schnall P., Dobson M., Rosskam E. (eds), Unhealthy Work: Causes, Consequences and Curves. Routledge, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Gram Quist H., Christensen U., Christensen K. B., Aust B., Borg V., Bjorner J. B. (2013) Psychosocial work environment factors and weight change: a prospective study among Danish health care workers. BMC Public Health, 13, 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubler T., Larkin I., Pierce L. (2018) Doing well by making well: the impact of corporate wellness programs on employee productivity. Management Science, 64, 4967–4987. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjimanolis A., Boustras G. (2013) Health and safety policies and work attitudes in Cypriot companies. Safety Science, 52, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hải H. T. (2012) Factors Influencing Organizational Commitment and Intention to Stay of Core Employees in Small-Medium Sized Companies in Hochiminh City. Master thesis. International School of Business, 10–47.

- Hart S. L. (1997) Beyond greening: strategies for a sustainable world. Harvard Business Review, Boston.

- Hassard J., Teoh K., Cox T., Dewe P. (2014) Calculating the Cost of Work-Related Stress and Psychosocial Risks. Risk Observatory Literature Review. European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, Luxembourg, pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Honda A., Date Y., Abe Y., Aoyagi K., Honda S. (2016) Communication, support and psychosocial work environment affecting psychological distress among working women aged 20 to 39 years in Japan. Industrial Health, 54, 5–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huta V., Waterman A. S. (2014) Eudaimonia and its distinction from hedonia: developing a classification and terminology for understanding conceptual and operational definitions. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15, 1425–1456. [Google Scholar]

- Iamandi I. (2011) Strategic approach of corporate social responsibility key drivers for increasing competitiveness at the European level. Economic Review, 3, 180–187. [Google Scholar]

- Iamandi I. E., Constantin L. G. (2012) Consolidating Human Resource Management through Corporate Social Responsibility Practices in Central and Southeastern Europe. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the International Conference on Management of Human Resources 2012: Management Leadership Strategy Competitiveness. Vol. I, Rosental Kft. Publishing House -248 SeeNews, 2011. South East Europe Top 100, SEE Top 100, Ed. 2011, pp. 6–7, http://top100.seenews.com/storage/seetop1002011.pdf.

- ILO. (2016). Workplace Stress: A Collective Challenge. EU-OSHA, Second European Survey of Enterprises on New and Emerging Risks (ESENER-2).

- Jain A., Leka S., Zwetsloot G. (2011) Corporate social responsibility and psychosocial risk management in Europe. Journal of Business Ethics, 101, 619–633. [Google Scholar]

- Jarinto K. (2010) Eustress: a key to improving job satisfaction and health among Thai managers comparing US, Japanese, and Thai companies using SEM analysis. NIDA Development Journal, 50, 101–129. [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. (2018) The Relationship of Employee Engagement and Employee Job Satisfaction to Organizational Commitment. Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies. Walden University.

- Kim B.-J., Nurunnabi M., Kim T.-H., Jung S.-Y. (2018) The influence of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: the sequential mediating effect of meaningfulness of work and perceived organizational support. Sustainability, 10, 2208. [Google Scholar]

- Kompier M. (2005) Assessing the psychosocial work environment ‘subjective’ versus ‘objective’ measurement. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 31, 405–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskela M. (2014) Occupational health and safety in corporate social responsibility reports. Safety Science, 68, 294–308. [Google Scholar]

- Kowal J., Roztocki N. (2015) Do organizational ethics improve IT job satisfaction in the Visegrád Group countries? Insights from Poland. Journal of Global Information Technology Management, 18, 127–145. [Google Scholar]

- Krainz K. D. (2015) Enhancing wellbeing of employees through corporate social responsibility context. Megatrend Review, 12, 137–154. [Google Scholar]

- LaMontagne A. D., Martin A., Page K. M., Reavley N. J., Noblet A. J., Milner A. J.. et al. (2014) Workplace mental health: developing an integrated intervention approach. BMC Psychiatry 14 Psychiatry, 2014, 14, 131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landsbergis P. A., Dobson M., LaMontagne A. D., Choi B., Schnall P., Baker D. B. (2017) Occupational stress. In Levy B. S., Wegman D. H., Baron S. L., Sokas R. K. (eds), Occupational and Environmental Health, 7th edition.Oxford University Press, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Lunau T., Siegrist J., Dragano N., Wahrendorf M. (2015) The association between education and work stress: does the policy context matter? PLoS One, 10, e0121573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macassa G., Francisco J. C., McGrath C. (2017) Corporate social responsibility and population health. Health Science Journal, 11, 528. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen I. E. H., Gupta N., Budtz-Jørgensen E., Bonde J. P., Framke E., Flachs E. M.. et al. (2018) Physical and psychosocial working conditions as predictors of musculoskeletal pain: a cohort study comparing self-reported and job exposure matrix measurements. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 75, 752–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. G., Bosma H., Hemingway H., Brunner E., Stansfeld S. (1997) Contribution of job control and other risk factors to social variations in coronary heart disease incidence. The Lancet, 350, 235–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartney K. (2015) Implementing CSR health initiatives. EMG, 11 January. http://www.emg-csr.com/csr-health-initiatives/ (last accessed 4 November 2019).

- Meyer J. P., Stanley D. J., Herscovitch L., Topolnytsky L. (2002) Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: a meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61, 20–52. [Google Scholar]

- Milner A., Butterworth P., Bentley R., Kavanagh A. M., LaMontagne A. D. (2015) Sickness absence and psychosocial job quality: an analysis from a longitudinal survey of working Australians, 2005-2012. American Journal of Epidemiology, 181, 781–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell R., Agle B., Wood D. (1997) Towards a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of Management Review, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G.; the PRISMA Group. (2009) Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6, e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mory L., Wirtz B. W., Göttel V. (2016) Factors of internal corporate social responsibility and the effect on organizational commitment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27, 1393–1425. [Google Scholar]

- Nadinloyi K. B., Sadeghi H., Hajloo N. (2013) Relationship between job satisfaction and employees mental health. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 84, 293–297. [Google Scholar]

- Nafeesa M. A. C., Venugopal V., Anbu V. P. (2018) Perceived work-related psychosocial stress and musculoskeletal disorders complaints among call centre workers in India–a cross sectional study. MOJ Anatomy & Physiology, 5, 80–85. [Google Scholar]

- Nasrullah N., Rahim M. (2014) CSR in Private Enterprises in Developing Countries. Evidences from the Ready-Made Garments Industry in Bangladesh. Springer Publications, Heidelberg.

- NIOSH. (2008) Expanding Our Understanding of the Psychosocial Work Environment: A Compendium of Discrimination, Harassment, and Work-Family Issues, pp. 1–260. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2008-104/pdfs/2008-104.

- North F. M., Syme S. L., Feeney A., Shipley M., Marmot M. (1996) Psychosocial work environment and sickness absence among British civil servants: the Whitehall II Study. American Journal of Public Health, 86, 332–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeidat B. Y., Altheeb S., Masa’deh R. (2018) The impact of internal corporate social responsibility on job satisfaction in. Modern Applied Science, 12, 105–120. [Google Scholar]

- Omer S. K. (2018) The impact of corporate social responsibility on employees job satisfaction. Journal of Process Management. New Technologies International, 6, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Özbilgin M. F., Beauregard T. A., Tatli A., Bell M. P. (2011) Work-life, diversity and intersectionality: a critical review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 13, 177–198. [Google Scholar]

- Peloza J. (2009) The challenge of measuring financial impacts from investments in corporate social performance. Journal of Management, 35, 1518–1541. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez S., Fernández-Salinero S., Topa G. (2018) Sustainability in organizations: perceptions of corporate social responsibility and Spanish employees’ attitudes and behaviors. Sustainability, 10, 3423. [Google Scholar]

- Pietersz G. (2011) Corporate Social Responsibility Is More Than Just Donating Money. KPMG International, Curaçao. [Google Scholar]

- Raub S., Blunschi S. (2014) The power of meaningful work. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 55, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Rugulies R., Madsen I. E. H., Nielsen M. B. D., Olsen L. R., Mortensen E. L., Bech P. (2010) Occupational position and its relation to mental distress in a random sample of Danish residents. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 83, 625–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Palomino P., Ruiz‐Amaya C., Knörr H. (2011) Employee organizational citizenship behaviour: the direct and indirect impact of ethical leadership. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences / Revue Canadienne Des Sciences de L'administration, 28, 244–258. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan R. M., Deci E. L. (2001) On happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadlowska-Wrzesinska J. (2017) Reducing the psychosocial risk at work as the task of socially responsible companies. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Safety, 1, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sarfraz M., Qun W., Abdullah M. I., Alvi A. T. (2018) Employees’ perception of corporate social responsibility impact on employee outcomes: mediating role of organizational justice for small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Sustainability, 10, 2429. [Google Scholar]

- Seivwright A. N., Unsworth K. L. (2016) Making sense of corporate social responsibility and work. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamir R. (2005) Mind the gap: the commodification of corporate social responsibility. Symbolic Interaction, 28, 229–253. [Google Scholar]

- Sowden P., Sinha S. (2005) Promoting Health and Safety as a Key Goal of the Corporate Social Responsibility Agenda. Health and Safety Executive Research Report 339.

- Stenfors C., Magnusson H. L., Oxenstierna G., Theorell T., Nilsson L.-G. (2013) Psychosocial working conditions and cognitive complaints among Swedish employees. PLoS One, 8, e60637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H., Turner J. C. (1986) The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Worchel S. and Austin W. G. (eds), Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Nelson-Hall, Chicago, pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tamm K., Eamets R., Mõtsmees P. (2010) Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility and Job Satisfaction: The Case of Baltic Countries. University of Tartu Faculty of Economics and Business Administration Working Paper 76–2010. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1717710. [DOI]

- Taouk Y., Spittal M. J., La Montagne A. D., Milner A. J. (2020) Psychosocial work stressors and risk of all-cause and coronary heart disease mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 46, 19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thang N. N. (2012) Human resource training and development as facilitators of CSR. Journal of Economics and Development, 14, 88–89. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaselli G., Garg L., Gupta V., Xuereb P. A., Buttigieg S. C. (2018) Corporate social responsibility communication research: state of the art and recent advances. In Saha D. (ed), Advances in Data Communications and Networking for Digital Business Transformation, Chapter 9. IGI Global, Hershey, PA, pp. 272–305. [Google Scholar]

- Tsourvakas G., Yfantidou I. (2018) Corporate social responsibility influences employee engagement. Social Responsibility Journal, 14, 123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Valcour M., Ollier-Malaterre A., Matz-Costa C., Pitt-Catsouphes M., Brown M. (2011) Influences on employee perceptions of organizational work-life support: signals and resources. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79, 588–595. [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen M., Stansfeld S. A., Fuhrer R., Ferrie J. E., Kivima M. (2012) Overtime work as a predictor of major depressive episode: a 5-year follow-up of the Whitehall II study. PLoS One, 7, e30719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vives A. (2006) Social and environmental responsibility in small and medium enterprises in Latin America. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 2006, 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Vivoll L., Vittersø S. J. (2012) Happiness, inspiration and the fully functioning person: separating hedonic and eudaimonic well-being in the workplace. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 7, 387–398. [Google Scholar]

- Vlachos P. A., Panagopoulos N. G., Rapp A. A. (2013) Feeling good by doing good: employee CSR-induced attributions, job satisfaction, and the role of charismatic leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 118, 577–588. [Google Scholar]

- Vveinhardt J., Grančay M., Andriukaitiene R. (2017) Integrated actions for decrease and/or elimination of mobbing as a psychosocial stressor in the organizations accessing and implementing corporate social responsibility. Engineering Economics, 28, 432–445. [Google Scholar]

- Wambui T. W., Wangombe J. G., Muthura M. W., Kamau A. W., Jackson S. M. (2013) Managing workplace diversity: a Kenyan perspective. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 4, 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Waring P., Edwards T. (2008) Socially responsible investment: explaining its uneven development and human resource management consequences. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 16, 135–145. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2010) Healthy Workplaces: A Model for Action for Employees, Workers, Policy Makers and Practitioners. WHO, Geneve, pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wisse B., van Eijbergen R., Rietzschel E. F., Scheibe S. (2018) Catering to the needs of an aging workforce: the role of employee age in the relationship between corporate social responsibility and employee satisfaction. Journal of Business Ethics, 147, 875–888. [Google Scholar]

- Yousaf H. Q., Ali I., Sajjad A., Ilyas M. (2016) Impact of internal corporate social responsibility on employee engagement: a study of moderated mediation model. International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied Research (IJSBAR), 30, 226–243. [Google Scholar]

- Zanko M., Dawson P. (2012) Occupational health and safety management in organizations. A review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 14, 328–344. [Google Scholar]

- Zientara P., Kujawski L., Bohdanowicz-Godfrey P. (2015) Corporate social responsibility and employee attitudes: evidence from a study of Polish hotel employees. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23, 859–880. [Google Scholar]

- Zwetsloot G., Leka S. (2008) Corporate Social Responsibility and Psychosocial Risk Management at Work. Prima-EF Consortium. http://www.prima-ef.org/prima-ef-guidance-sheets.html (last accessed 4 November 2019).

- Zwetsloot G., Starren A. (2004) Corporate Social Responsibility and Safety and Health at Work. European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, Luxembourg. http://osha.europa.eu/en/publications/reports/210/view (last accessed 4 November 2019).