Graphical abstract

Keywords: Biodiesel, Ultrasound assisted, Transesterification, Cavitation, Measurement uncertainty

Highlights

-

•

Ultrasound assisted synthesis of biodiesel performed without external heating source and stirring mechanical.

-

•

Understanding the effect of ultrasonic power, ultrasonic frequency and alcohol to oil molar ratio.

-

•

Ultrasound can be used as a tool for a preliminary analysis of biodiesel quality.

-

•

Frequencies of 1 MHz and 3 MHz and US power lower than 10 W were used.

-

•

Ultrasonic method has electric power consumption 4 times lower than conventional method.

Abstract

In this work, high frequency and low power ultrasound without external heating source and mechanical stirring in biodiesel production were studied. Transesterification of soybean oil with methanol and catalyzed by KOH was investigated using ultrasound equipment and ultrasonic transducer. The effect of ultrasonic output power (3 W–9 W), ultrasonic frequency (1 MHz and 3 MHz), and alcohol to oil molar ratio (6:1 and 8:1) have been investigated. The increase in ultrasonic power provided higher conversion rates. In addition, higher conversion rates were obtained by increasing the ultrasonic frequency from 1 MHz to 3 MHz (48.7% to 79.5%) for the same reaction time. Results also indicate that the speed of sound can be used to evaluate the produced biodiesel qualitatively. Further, the ultrasound system presented electric consumption (46.2 W∙h) four times lower than achieved using the conventional method (211.7 W∙h and 212.3 W∙h). Thus, biodiesel production using low power ultrasound in the MHz frequency range is a promising technology that could contribute to biodiesel production processes.

1. Introduction

Chemically, biodiesel is a mixture of long chains of fatty acids of methyl esters (FAME), generally produced through the transesterification of renewable lipid feedstock [1], [2], [3], [4]. Conventionally, triglycerides transesterification is performed via mechanical stirring using short-chain alcohol, homogeneous catalyst, high temperatures, high stirring speed and long reaction times [5], [6]. Although heterogeneous catalysis appears to be promising for biodiesel production, there is a lack of protocols that can help it meet the requirements of its large-scale application [7], [8], [9], [10].

The high cost of production, mainly due to raw material price and energy efficiency, is one of the limiting factors for the large-scale commercialization of biodiesel [5], [11], [6]. Ultrasonic irradiation has proved to be a valuable tool technically feasible, energy saving and efficient to produce biodiesel. Ultrasound provides the necessary mechanical energy to disturb the phase limit between the alcohol and oil due to the collapse of cavitation bubbles [6], [12], [13], [14].

Nowadays, there are many studies that use low frequency and high-power ultrasound typically below 1 MHz and applying hundreds of watts (38 W to 1000 W, within the cited studies) for biodiesel production, as show Table 1.

Table 1.

Previous articles reporting biodiesel production from vegetable oils and homogeneous catalyst by ultrasound irradiation.

| Oil feedstock | Ultrasonic reactor type | Frequency [kHz]/Power [W] | T [°C] | Time [min] | Alcohol:oil molar ratio | Catalyst [wt%] | Yield [%] | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soybean | Probe | 20; 28 / 400 | 45 | 45 | 8:1 | KOH; 1.8 | 96.5 | [15] |

| Soybean | Bath | 40 / 800 | 35 | 60 | 5:1 | KOH; 0.7 | 95.5 | [16] |

| Soybean | Probe* | 20 / 400 | 30 | 30 | 6:1 | KOH; 0.7 | 98 | [17] |

| Soybean | Horn* | 19.7 / 150 | 45 | 30 | 6:1 | NaOH; 1 | 98 | [18] |

| Palm | Bath | 20; 50 / 400 | 45 | 60 | 6:1 | NaOH; 1 | 94 | [19] |

| Palm | Bath | 28; 40; 70 / 300 | 60 | 45 | 3:1 | KOH; 1 | 93 | [20] |

| Rapeseed | Uninformed* | 40 / 400 | 40 | 40 | 6:1 | NaOH; 1 | 75.6 | [21] |

| Canola | Transducer | 20 / 1000 | 35 | 50 | 5:1 | KOH; 0.7 | 99 | [22] |

| Sunflower | Horn* | 24 /200 | 60 | 60 | 7:1 | NaOH; 2 | 95 | [23] |

| WCO | Horn | 20/ 200 | 45 | 40 | 6:1 | KOH; 1 | 89% | [24] |

| WFO | Probe | 24 / 400 | 55 | 30 | 6:1 | KOH; 1 | 79.6 | [25] |

* Mechanical stirring with ultrasonic irradiation.

Review papers on the progress of the intensification technologies for biodiesel production can provide more information on the use of technology [6], [26]. As seen, these studies use high power ultrasound, external heating source, and some cases mechanical stirring, increasing the amount of energy spent in the processes. Thus, to the best of our knowledge, there is a lack of reports into biodiesel production by low power (up to 10 W) and high-frequency ultrasound, mainly without external heating and mechanical stirring.

Moreover, there is a lack of knowledge to be exploited concerning a study of the effect of the ultrasonic output power (calibrated) on the system and consequently on transesterification reaction. Some studies report the assessment of the effect of nominal power (electrical input or output power) on transesterification [24], [25], [27], [28], [29]. None of these have presented the ultrasonic power calibration, i.e., estimated the ultrasonic output power emitted by ultrasound device. This determination is important to the discussion about ultrasonic power effects. A metrological approach to the ultrasonic parameters involved in the process is necessary to ensure the quality and reliability of measurement results [30], [31].

Regarding the use of high-frequency ultrasound in transesterification reaction, it is known that the ultrasonic frequency influences cavitation bubble size and consequently in rate reaction [32], [33], [34]. Few studies investigated the use of high-frequency ultrasound [35], [36], [37]. A previous report uses high frequency to compare the ultrasonic cavitation with mechanical stirring [35]. It is not a complete study since the ultrasonic power calibration was not performed. Thus, it cannot ensure that in assessing frequency influence, the output powers generated by both systems are similar.

Aghbashlo et al. [36], [37] developed a low power (31 W) and high frequency (1.7 MHz) ultrasonic reactor with a heating element (40 °C-60 °C; 500 W) for transesterification reaction. As seen, the ultrasonic irradiation is not the only source of energy. In addition, calibration of ultrasonic output power and evaluation of the effect of high frequency variation on transesterification reaction was not performed. The metrological aspects, such as measurement uncertainties, also were not considered.

Therefore, the aim of this paper was to assess the effect of low power ultrasonic (calibrated) and high-frequency on transesterification of soybean oil, without the aid of external source and mechanical stirring. This approach can make the system even more environmentally friendly and economical for industrial applications. Moreover, this research revealed the importance of ultrasonic power calibration to study the effects of cavitation and importance of insertion of metrology in experimental analysis.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Materials

Soybean oil (Liza©, Brazil) as the triglyceride source, methanol (99.8% of purity from Vetec©, Brazil) as the alcohol, and Potassium Hydroxide (B'Herzog©, Brazil) as the essential catalyst were used for biodiesel production. Magnesium sulfate (B'Herzog©, Brazil) was used in the biodiesel purification.

2.2. Experimental setup

Two therapeutic ultrasound equipment (models Sonomed 4144 and 4134, Carci, Brazil) were used in the transesterification reactions. The ultrasonic transducers, both with 36.5 mm diameters, operated in continuous mode at frequencies of 1 MHz and 3 MHz. In this device, different than the use of ultrasonic probe, there is no separation between the transducer and the liquid surface (direct application), thus, the volume of wave propagation is more confined [38]. The transducer was positioned at the surface of the liquid with the aid of a micrometrical graduated positioning system (Newport Corporation, CA, USA), as shown in Fig. 1. The transesterification reaction without ultrasonic irradiation was carried out with mechanical stirring at 200 rpm, 520 rpm and 800 rpm (model 713D, Fisatom, Brazil) and external heating at 40 °C (model 557, Fisatom, Brazil) [31].

Fig. 1.

Experimental setup used in the production of biodiesel assisted by ultrasound. (a) Ultrasonic equipment, (b) positioning system, (c) ultrasonic transducer, and (d) glass reactor.

2.3. Ultrasonic output power calibration

The amount of electrical energy spent prior to transformation to the mechanical vibration does not determine the amount of acoustic energy produced [39]. Thus, it is necessary to estimate the ultrasonic output power produced by ultrasound device and introduced in the system. The ultrasonic power calibration was performed according to the technical standard IEC 61161 [40]. There are alternative methods available about measuring of ultrasonic power for sonochemical reaction by calorimetry or chemical dosimetry [39], [41].

The technical standard IEC 61161 [40] specifies a measurement method to determine the total emitted acoustic power of ultrasonic transducers based on a radiation force balance exerted by the ultrasonic field. The measurement system used was evaluated through participation in the BIPM key-comparison CCAUV.U-K3.1 [42]. More details on power calibration are described in [43]. The calibration was performed at the frequencies of 1 MHz and 3 MHz and nominal power of 3.6 W, 5.4 W and 7.2 W. The results of measurement ultrasonic output power and their respective expanded uncertainties are shown in Table 2. The ultrasonic systems calibration revealed that the maximum ultrasonic output power for the 1 MHz equipment was 9.06 W ± 0.56 W and for 3 MHz equipment was 5.36 W ± 0.25 W.

Table 2.

Results of ultrasonic output power measurement for equipment’s operating a 1 MHz and 3 MHz.

| Nominal power [W] | Equipment 1 MHz |

Equipment 3 MHz |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured power [W] | U [W] | Measured power [W] | U [W] | |

| 3.60 | 4.22 | 0.14 | 2.80 | 0.19 |

| 5.40 | 6.51 | 0.19 | 4.11 | 0.22 |

| 7.20 | 9.06 | 0.56 | 5.36 | 0.25 |

2.4. Transesterification reaction

The transesterification of soybean oil was carried out in a mini reactor with 250 ml capacity. Reagents were added to the reactor without preheating. Ultrasonic irradiation was directly provided into the solution. The catalyst (KOH) concentration (1.5% in mass) and alcohol to oil molar ratios (6:1 and 8:1) used in all reactions were chosen according to the parameters commonly found in the literature [44]. The different operating conditions as the variation of the molar ratio (6:1 and 8:1), ultrasonic power (3 W, 5 W, and 9 W), and ultrasonic frequency (1 MHz and 3 MHz) were used to promote different production routes (8 routes) and to prove the concept.

The total reaction time was 40 min, and all ultrasound-assisted reactions were performed without external heating or mechanical stirring. The temperature of the reaction medium was monitored throughout the process with a type K thermocouple previously calibrated (resolution: 0.001 °C; expanded uncertainty: 0.16 °C), connected to a data acquisition unit (model 34970A, Agilent Technologies, CA, USA).

2.5. Biodiesel purification

The phase separation was carried out in a separation funnel at room temperature. Acid solution of HCl 5% by weight was added to interrupt the reaction, neutralize biodiesel, and promote phase separation. The crude ester phase was purified with distilled water until the pH of the washing water stays neutral. This washing was performed to remove some residues in biodiesel, including excess alcohol and catalyst, glycerin, and soap. After the extraction steps (commonly called biodiesel washing), magnesium sulfate (B'Herzog©, Brazil) was added to the biodiesel to remove moisture. Then, the drying agent was separated from the biodiesel by simple filtration. The final products were analyzed to determine the speed of sound.

2.6. Analytical method

The transesterification is usually assessed by reference method gas chromatography (GC) using a European standard EN 14103 [45]. However, alternative techniques as Hydrogen Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (1H NMR) have been successfully used to quantify the conversion [46], [47], [48]. Although esters quantification by 1H NMR cannot be considered a gold standard or a reference method, this analysis allows evaluating the content of methyl ester concerning the triacylglycerol in the organic phase. Also, 1H NMR is a simple and faster technique than gas chromatography (GC) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [46].

In this work, the methyl ester content was quantified by 1H NMR based on an approach collected from the literature [47], [48]. Aliquots were taken during the reaction at pre-determined time intervals (0, 5, 10, 20 and 40 min) to show the progress of the transesterification reaction. After biodiesel purification, the samples were dissolved in CDCl3 for 1H NMR analysis on a 500 MHz spectrometer (model VNMRS, Varian Instruments, Germany). The conversion rate was calculated by equation (1), using the relationship between the areas of the methyl ester hydrogen signal ( = CH3OCO– δ 3.7 ppm) and of the a-carbonyl methylene hydrogen signal ( = –OCOCH2– δ 2.2–2.4 ppm) [47], [48]. The 2/3 factor is related to the different numbers of hydrogen atoms in methyl and methylene groups.

| (1) |

2.7. Estimation of energy consumption

The use of ultrasound has the advantage of reducing energy consumption when compared to conventional method to produce biodiesel. All apparatus used in the process were electrically rated. For the conventional method, the mechanical stirrer and heating bath were studied. For the ultrasonic method, only the US generator was considered since there was no other energy source in this method. The electric power used in this calculated was provided by the manufacturer in the equipment manual. The electric power consumption (EPC) was calculated according to equation (2) [49].

| (2) |

For the conventional system, the electrical consumption was considered for 10 and 40 min of reaction, while for the ultrasound method considered 40 min. These times were selected based on the conversion rates obtained [50].

2.8. Speed of sound

Characterization of liquids using ultrasonic techniques has attracted attention because they are non-destructive, fast, minimally invasive, and technically well-established worldwide for a long time [31], [50], [51], [52]. The biodiesel produced was characterized by a study of ultrasonic velocity behavior with the temperature increasing in a range of 20 °C to 50 °C. Ultrasound equipment is a relatively low-cost one, typically being bought by a few thousands of US$. For analysis by ultrasound, it was employed the methodology described in the literature [50], [53], which uses the pulse/echo method and a transducer with a nominal frequency of 1 MHz and active element diameter of 12.7 mm model A303S (NDT-Panametrics – Olympus Corporation, Japan). The propagation distance was characterized using de-ionized water as a reference. Five ultrasonic velocity measurements were performed as a function of temperature under repeatability conditions for each biodiesel sample.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Uncertainties were assessed according to the Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement (GUM) [54] and were determined based on the type A (random) and type B (systematic) evaluation method. The normalized error (En) was calculated according to [55] and used to establish the statistical equivalence of the SoS of the biodiesels produced (p = 0.05). The evaluation criterion is given by: ≤ 1.0 if the compared results are statistically equivalent, or > 1.0 if the compared results are not statistically equivalent. All statistical analyses were done based on [56].

3. Results and discussion

3.1. The conversion rate of triglycerides to esters

As mentioned previously, the conversion rate of triglycerides to FAME was determined quantitatively by 1H NMR to evaluate the effect of molar ratio, ultrasonic power, and ultrasonic frequency.

3.2. Effect of reactant molar ratio

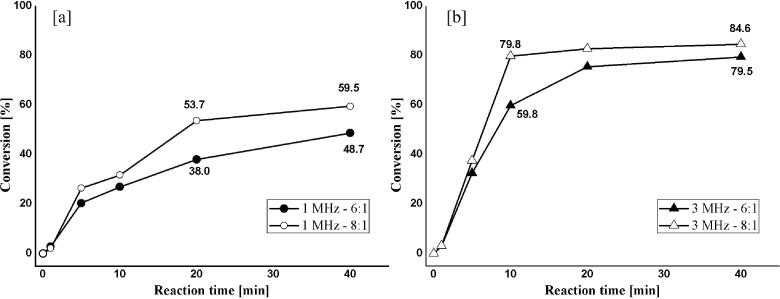

The effect of molar ratio on conversion to FAME was studied in molar ratios of methanol: soybean oil of 6:1 and 8:1 at the same ultrasonic power (5 W). This effect was assessed in reactions performed with ultrasonic frequencies of 1 MHz and 3 MHz.

Fig. 2a shows that from 10 min of a 1 MHz reaction, the conversion rate increased with an increasing molar ratio from 6:1 to 8:1. After 40 min of reaction, the conversion rate using an 8:1 M ratio (59.5%) was higher than the conversion rate for a 6:1 M ratio (48.7%). In Fig. 2b, at 10 min, by increasing the molar ratio from 6:1 to 8:1, the conversion rate increased significantly. The 8:1 M ratio reaction is visibly faster, achieving a conversion rate of 79.8% after 10 min, and stabilizes with only 20 min of reaction.

Fig. 2.

Effect of reactant molar ratio (6:1 and 8:1) on conversion to FAME. (a) Ultrasonic frequency of 1 MHz; (b) Ultrasonic frequency of 3 MHz.

The results show that both configurations, 1 MHz and 3 MHz, achieve higher conversion levels in a shorter period within higher molar ratios. It occurs due to methanol excess that shifts the reaction equilibrium towards FAME production and increases the number of cavitation bubbles due to greater ease of cavitation in methanol than in oil [15], [57]. Than et al. [22] have reported similar results with increasing molar ratio on transesterification of canola oil with methanol using low-frequency ultrasound (20 kHz). In a study by Fan et al. [58], by increasing the molar ratio from 3:1 to 6:1 utilizing a frequency of 40 kHz, the yield also increased. A similar study on the transesterification of soybean oil by ultrasound (20 kHz −28 kHz) reported an optimum reactant molar ratio of 8:1 [15]. Analyzing the obtained trends, one can say that the increase of yields of methyl esters due to excess methanol does not depend on the ultrasonic frequency (high or low) used in the measurement system.

3.3. Effect of ultrasonic power

The calibration of ultrasonic output power and the estimation of measurement uncertainty make comparable, the results reported here. Ultrasonic power influence studies were carried out by varying the ultrasonic power (3 W, 5 W, and 9 W) and the alcohol to oil molar ratio. In contrast, the ultrasonic frequency was kept constant (1 MHz). Fig. 3 shows the effect of ultrasonic power on the conversion to FAME.

Fig. 3.

Effect of ultrasonic power on conversion to FAME (Molar ratio of methanol to triglyceride 6:1 and 8:1, @1 MHz).

Analyzing the reaction performed with 3 W, one notices that after 20 min, reactions in both molar ratios achieve stability with low conversion rates. For the reaction with the power of 5 W, a gradual increase is observed, and conversions of 48.7% and 59.5% were obtained. On the other hand, when the power was increased to 9 W, the conversion to FAME increased considerably for the first 10 min. At the end of the reaction, were obtained conversions of 80.5% and 85.8% (molar ratio 6:1 and 8:1, respectively). As expected, the increase of ultrasonic power is a factor that generates positive effects on cavitation and reaction yield. It occurs due to the higher pressure generated during bubble collapse, increasing the system local temperature favoring the reaction [57].

The thermal effects of ultrasound caused simply by the bubbles collapse was monitored throughout the reactions, as shown in Fig. 4. Experimental results indicate that reactions within higher powers (9 W) reach higher temperatures, leading to higher conversion rates. The temperature increased up to about 47 °C after 40 min of reaction. With the collapse of the cavitation bubbles, local hotspots are developed that have high temperatures and high pressures [59]. The transesterification of triglycerides has been proved to be an endothermic reaction [60], [61], and, according to Le-Chatelier's principles, an increase in reaction temperature will favor the forward reaction. Furthermore, higher temperatures increase the movement of the particles in the medium, leading to a higher rate of successful collisions. Hence, the biodiesel conversion rate increases as well.

Fig. 4.

Thermal effect of ultrasound in the production of soybean methyl biodiesel using different ultrasonic powers (3 W, 5 W, and 9 W @1 MHz), and different molar ratios (6:1 and 8:1).

It is important to note that, in the current study, 9 W was established as an optimal acoustic power for the transesterification process. Literature shows that similar studies [24], [25], [27], [28] report much higher ultrasonic power as optimal. Also, it is not usual to find studies that calibrated the emitted power to determine power accurately. Hingu et al. [24] used 200 W in transesterification of frying oil with methanol to obtain 89% conversion. Maghami et al. [25] reported 300 W (about 30 times higher than the one used in this current study) as a necessary power to reach ~ 90% conversion in transesterification using fish oil. Poosumas et. al. [27] applied the ultrasonic power of 800 W in the transesterification of palm oil and biodiesel yield of 80% after 240 min, while Nakayama et al. [28] reported an optimal power of 120 W with 90% of conversion. The comparison with the literature and the analysis of trends has allowed understanding that it is possible to obtain compatible conversions using lower ultrasonic power.

3.4. Effect of ultrasonic frequency

Ultrasonic frequency influence studies were carried out by varying the ultrasonic frequency (1 MHz and 3 MHz) and the alcohol to oil molar ratio, whilst ultrasonic power kept constant (5 W). The results are presented in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Effect of ultrasonic frequency on conversion to FAME. (a) The molar ratio of 6:1; (b) Molar ratio of 8:1.

With the ultrasonic frequency variation, the conversion rate increased for both molar ratios: 48.7% to 79.5% for molar ratio of 6:1 (Fig. 5a) and 59.5% to 84.6% for molar ratio of 8:1 (Fig. 5b). Regardless of the molar ratio, after 10 min, the conversion rate difference is remarkable due to the increase of ultrasonic frequency. The conversion rates for 3 MHz reactions are higher than the ones with 1 MHz. Different ultrasonic frequencies generate cavitation bubbles with different diameters. According to [32], [33], cavitation bubble size is inversely related to ultrasonic frequency. It is because cavitation bubbles have more time to grow at a lower frequency since they have a higher wavelength. Hence, lower frequencies require less energy to produce bigger cavitation bubbles. However, at the same power, increasing the frequency will also increase the number of smaller bubbles in the medium, which will increase the rate of collision and, consequently, the conversion rate.

Fig. 6 shows the 1H NMR monitoring of the transesterification reaction of soybean oil by ultrasound (3 MHz; 5 W and 6:1). Results show conversion due to appearance of FAME peaks (3.7 ppm). The 1H NMR spectra for other routes shown in Fig. 5 are provided in Supplementary material.

Fig. 6.

1H NMR spectra of soybean oil transesterification reaction by high frequency and low power ultrasound at different reaction times by ultrasonic frequency of 3 MHz. (Ultrasound power 5 W and molar ratio alcohol: oil of 6:1).

In addition to the conversion, the temperature also was monitored along with all the reactions (Fig. 7). It is known that temperature as one of the most critical parameters for endothermic reactions.

Fig. 7.

Temperature of the reaction medium in the production of soybean methyl biodiesel at different ultrasonic frequencies at the same output power (5 W).

According to Fig. 7, the temperature of the medium as a function of the time is similar in all reactions studied. Since the reactions were performed without external heating and maintaining the same ultrasonic power (5 W), the temperature variation was produced only by acoustic cavitation effects. This shows that after 40 min of reaction, the total amount of thermal energy released from the collapse of the bubbles was similar for both frequencies. In this study, the transesterification process was benefited from the larger number of smaller energy implosions created by 3 MHz than the fewer but more intense cavitation implosions created by 1 MHz.

Few studies in the literature evaluated the frequency influence in the transesterification reaction. Poosumas et al. [27] investigated the effect of ultrasonic frequency (20 kHz, 50 kHz, and both) on transesterification of palm oil. It was found that a frequency of 50 kHz provided a higher biodiesel yield than that of a frequency of 20 kHz. Manickam et al. [20] used a triple frequency ultrasonic reactor (28 kHz, 40 kHz, and 70 kHz) on transesterification using palm oil. Single, dual, and triple frequency modes of operation have been compared, and it has been observed that the cavitation effects were higher for the triple frequency. Bhangu et al. [62] studied the effect of different ultrasonic frequencies (22 kHz, 44 kHz, 98 kHz, and 300 kHz) on the enzymatic transesterification of canola oil with methanol. They reported that from 22 kHz to 44 kHz, the yield of FAME increased, but when increasing to 98 kHz and 300 kHz, the yield decreased.

Analysis of the literature [20], [27], [62] revealed that several experimental parameters (power employed, type of system, transducer diameter, transducer position, and combined of two frequencies) could affect the intensity of acoustic cavitation when increasing the frequency. Hence, the results presented in the current work are relevant. Although the conversion achieved is less than 96.5%, it was possible to prove that the proposed technology (without mechanical agitation and external heating) has potential. Still, optimizations are necessary to achieve the conversion required by the standards.

3.5. Comparison of ultrasound cavitation with conventional stirring

Many studies have already demonstrated the efficiency of ultrasound when comparing to conventional stirring [16], [19], [20], [35]. However, they do not explore the advantage of savings in energy consumption. Conversion rates and electrical consumption for the ultrasound and conventional methods were compared. The estimation of energy consumption for both methods was made based on information provided by the equipment manufacturer, as shown in Table 3 and Fig. 8.

Table 3.

Conversion rate and electric power from the equipment by conventional and ultrasound transesterification methods.

| Method | Conversion rate [%] | Apparatus | Electric power [W] | Time [min] | Time [h] | Electric Power Consumption [W∙h] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional [200 rpm; 40 °C]* | 87.0 | MSa/HBb | 70; 1200 | 10 | 0,166 | 211.7 |

| 88.3 | 40 | 0,666 | 846.7 | |||

| Conventional [520 rpm; 40 °C]* | 90.8 | MSa/HBb | 74; 1200 | 10 | 0,166 | 212.3 |

| 91.3 | 40 | 0,666 | 849.3 | |||

| Conventional [800 rpm; 40 °C] | 91.8 | MSa/HBb | 77.5; 1200 | 10 | 0,166 | 212.9 |

| 92.1 | 40 | 0,666 | 851.7 | |||

| Ultrasound [1 MHz; 9 W] | 80.5 | USc | 70 | 20 | 0,333 | 23.1 |

| 40 | 0,666 | 46.2 | ||||

| Ultrasound [3 MHz; 5 W] | 79.5 | USc | 70 | 20 | 0,333 | 23.1 |

| 40 | 0,666 | 46.2 |

a- Mechanical Stirrer; b- Heating Bath; c - Ultrasound equipment.

* Data taken from the literature [31].

Fig. 8.

Electric power consumption and conversion for the ultrasound and conventional method for producing biodiesel.

Results in Table 3 and Fig. 8 showed that the ultrasound method reached similar conversions to that obtained by the conventional method. An electric power consumption comparison (Fig. 8) proved the advantage of ultrasound in reducing energy consumption. After 10 min, the conventional system achieves a conversion of 90.8% and 91.7% at 520 rpm and 800 rpm, respectively. However, the conventional method consumed 4 times more energy for 10 min (211.7 W∙h and 212.3 W∙h) when compared to 40 min of reaction by ultrasonic method (46.2 W∙h). In addition, according to Fig. 3, Fig. 7, the reaction using ultrasound reaches equilibrium after 20 min, presenting an even lower electric energy consumption, corresponding to 23.3 Wh. This consumption is about nine times smaller than conventional method. If we consider the total reaction time for the conventional method, the electric power consumption is higher. The EPC is equal to 846 W∙h, 849.3 W∙h and 851.7 W∙h for reactions performed with 200 rpm, 520 rpm and 800 rpm, respectively. The lack of mechanical stirring and the external heating source brings advantages in terms of necessary electrical consumption. These results show that biodiesel production assisted by ultrasound high-frequency and low power is more sustainable and thus proves to be an alternative way to produce biodiesel. In short, one can conclude that ultrasound can achieve similar levels of conversion, consuming only one-fourth of the energy required that the conventional method.

3.6. Speed of sound in biodiesel

The speed of sound (SoS) was determined as a function of temperature for the produced biodiesel for both frequencies (1 MHz and 3 MHz) and both alcohol to oil molar ratios (6:1 and 8:1). According to Baesso et al. [50], the SoS could be used to distinguish biodiesels considered different from each other based on qualitative evaluation. Thus, from the five measurements performed for each of the four different routes used to produce biodiesel, adjusted curves were established based on the linear regression data. The speed of sound and its uncertainty for different temperatures are displayed in Table 4 and Fig. 9.

Table 4.

Speed of sound for biodiesel analyzed. Adjusted values from five repetitions performed from 20 °C to 50 °C with their respective expanded uncertainties (p = 0.95).

| T [°C] | 1 MHz and 6:1 |

1 MHz and 8:1 |

3 MHz and 6:1 |

3 MHz and 8:1 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SoS [m s−1] |

U [m s−1] |

SoS [m s−1] |

U [m s−1] |

SoS [m s−1] |

U [m s−1] |

SoS [m s−1] |

U [m s−1] |

|

| 20 | 1450.8 | 4.3 | 1454.0 | 3.1 | 1435.0 | 4.4 | 1439.0 | 5.2 |

| 25 | 1435.1 | 4.4 | 1438.2 | 3.2 | 1419.9 | 4.6 | 1423.3 | 5.1 |

| 30 | 1419.5 | 4.3 | 1422.4 | 3.2 | 1404.7 | 4.5 | 1407.6 | 5.2 |

| 35 | 1403.8 | 4.4 | 1406.6 | 3.4 | 1389.6 | 4.6 | 1391.9 | 5.3 |

| 40 | 1388.2 | 4.5 | 1390.8 | 3.5 | 1374.5 | 4.7 | 1376.2 | 5.3 |

| 45 | 1372.5 | 4.6 | 1375.0 | 3.7 | 1359.4 | 4.8 | 1360.5 | 5.4 |

| 50 | 1356.9 | 4.7 | 1359.2 | 3.8 | 1344.2 | 4.9 | 1344.8 | 5.6 |

Fig. 9.

Speed of sound as a function of temperature for soybean oil and four biodiesels produced, with expanded uncertainty. Legend: (▲) data from Oliveira et al. [53].

The four biodiesels were statistically compared to each other using the normalized error method [55] to determine if the measured values of their speed of sound are equivalent or not. The evaluations were performed in pairs, and Table 5 shows the results of this comparison.

Table 5.

Normalized error results for the evaluation of propagation velocity among the biodiesel produced.

| T [°C] | 1 MHz 6:1–8:1 |

3 MHz 6:1–8:1 |

6:1 – 1 MHz 6:1 – 3 MHz |

8:1 – 1 MHz 8:1 – 3 MHz |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| En | En | En | En | |

| 20 | 0.62 | 0.58 | 2.56 | 2.49 |

| 25 | 0.57 | 0.50 | 2.40 | 2.48 |

| 30 | 0.56 | 0.42 | 2.38 | 2.43 |

| 35 | 0.51 | 0.33 | 2.23 | 2.34 |

| 40 | 0.47 | 0.25 | 2.10 | 2.30 |

| 45 | 0.43 | 0.16 | 1.98 | 2.22 |

| 50 | 0.39 | 0.08 | 1.86 | 2.13 |

According to Table 5, biodiesels produced using the same ultrasonic frequency were considered statistically equivalent. Therefore, the variation of the molar ratio does not seem to affect the speed of sound in biodiesel produced with the same frequency (1 MHz or 3 MHz). However, it was observed that the values of the speed of sound for biodiesel produced using different ultrasonic frequencies were considered statistically non-equivalent , i.e., the variation of ultrasonic frequencies seems to affect the speed of sound of the produced biodiesel. Thus, according to the results, the speed of sound was found to help identify biodiesel produced by different ultrasonic frequencies.

Furthermore, as visible in Fig. 9, biodiesel produced with an ultrasonic frequency of 3 MHz has a lower propagation velocity. According to the analyses of 1H NMR (Fig. 5), reactions carried out with 3 MHz obtained higher conversion rates than reactions at 1 MHz. Thus, the ester content found corroborates the results of SoS, since the higher the percentage of fatty acid methyl ester (FAME), the more decreases the SoS in biodiesel [50].

According to Laesecke, Fortin, and Splett [30], soybean biodiesel SRM (B100), which is a standard reference material of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), has at 20 °C an SoS of 1412.58 m s−1 (U = 0.30 m s−1, p = 0.95). In comparison, at 50 °C the SoS is 1307.09 m s−1 (U = 0.38 m s−1, p = 0.95). In the present study, the biodiesel with SoS closest to the reference material values was biodiesel produced with a frequency of 3 MHz and a molar ratio of 8: 1.

This biodiesel (3 MHz-8:1) achieved 84.6% of conversion and has a sound velocity of 1439.0 m s−1 (U = 5.2 m s−1; p = 0.95) 20 °C, and at 50 °C the speed of sound is 1344.8 m s−1, as shown in Table4. When compared to the reference material [30], this biodiesel presents lower conversion and higher SoS. That is, higher ester contents decrease the SoS in the final product. Thus, it is possible to affirm that among the frequencies studied here and with the output power used, 3 MHz is the most appropriate frequency for soybean biodiesel production assisted by ultrasound.

4. Conclusions

The low-power ultrasound at 1 MHz and 3 MHz frequencies provided the mechanical energy required to homogenize the reagents. Reactions were carried out without the aid of heating bath and mechanical stirring, at relatively short reaction times (20–40 min) and with reasonable conversion rates (about 85%–80%). The increase of ultrasonic power, molar ratio alcohol: oil, and ultrasonic frequency were directly related to higher conversion rates. Among the frequencies studied herein, regardless of the molar ratio used, the best ultrasonic frequency for biodiesel production was 3 MHz. The ultrasound method resulted in a significant decrease in electric power consumption and achieved conversions closed to the conventional method. Ultrasound can also be used as a qualitative tool for a preliminary analysis of biodiesel's highest FAME concentration through the SoS. The proposed study can be performed “inline” as a survey carried out before the analytical methods used in chemistry. Measurement uncertainties provided reliability in the experimental results, and the metrological approach adopted was necessary for the development of this study. Finally, biodiesel production assisted by low-power ultrasound in 1 MHz and 3 MHz frequencies has been shown as a promising alternative that is simple and effective. However, it needs optimization to promote the increase of conversion, making the method highly satisfactory. In addition, effects such as transducer position, the number of transducers, among others, need to be investigated in future work. Thus, the method developed in this work may in the future contribute to biodiesel production processes.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (grants 312.501/2017-0 [RCF], 306.198/2017-7 [AVA], 430.376/2018-9 [RCF], and 307.562/2020-4 [RCF]) and the Research Support Foundation of the State of Rio de Janeiro (grant E-26/201.563/2014 [RCF]). The authors are grateful to the Chemical Metrology group of INMETRO for its support with the chemical analysis.

Ethical approval was not required as the data were collected from the public literature, legislation database, technical standards, and experiments in the laboratory. No humans or animals were studied in this research.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105709.

Contributor Information

André V. Alvarenga, Email: avalvarenga@inmetro.gov.br.

Rodrigo P.B. Costa-Félix, Email: rpfelix@inmetro.gov.br.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Issariyakul T., Dalai A.K. Biodiesel from vegetable oils. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014;31:446–471. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banković-Ilić I.B., Stojković I.J., Stamenković O.S., Veljkovic V.B., Hung Y.-T. Waste animal fats as feedstocks for biodiesel production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014;32:238–254. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2014.01.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tran T.T.V., Kaiprommarat S., Kongparakul S., Reubroycharoen P., Guan G., Nguyen M.H., Samart C. Green biodiesel production from waste cooking oil using an environmentally benign acid catalyst. Waste Manage. 2016;52:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2016.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen J., Li J., Dong W., Zhang X., Tyagi R.D., Drogui P., Surampalli R.Y. The potential of microalgae in biodiesel production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018;90:336–346. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2018.03.073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.M. Tabatabaei, M. Aghbashlo, M. Dehhaghi, H. Kazemi, S. Panahi, A. Mollahosseini, M. Hosseini, M.M. Soufiyan, Reactor technologies for biodiesel production and processing: A review. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science, v.74, p. 239–303, 2019. Thangaraj, B.; Solomon, P.R.; Muniyandi, B.; Ranganathan, S.; Lin, L. Catalysis in biodiesel production – a review. Clean Energy, v.3 (1), p.2–23, 2019. DOI: 10.1093/ce/zky020.

- 6.Chuah L.F., Klemeš J.J., Yusup S., Bokhari A., Akbar M.M. A review of cleaner intensification technologies in biodiesel production. J. Cleaner Prod. 2017;146:181–193. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malani S., Shinde V., Ayachit S., Goyal A., Moholkar V.S. Ultrasound-assisted biodiesel production using heterogeneous base catalyst and mixed non–edible oils. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019;v,52:232–243. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De A., Boxi S.S. Application of Cu impregnated TiO2 as a heterogeneous nanocatalyst for the production of biodiesel from palm oil. Fuel. 2020;265:117019. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2020.117019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohadesi M., Aghel B., Maleki M., Ansari A. Production of biodiesel from waste cooking oil using a homogeneous catalyst: Study of a semi-industrial pilot of microreactor. Renewable Energy. 2019;136:677–682. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2019.01.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avhad M.R., Marchetti J.M. A review on recent advancement in catalytic materials for biodiesel production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015;50:696–718. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2015.05.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbaszaadeh A., Ghobadian B., Omidkhah M.R., Najafi G. Current biodiesel production technologies: a comparative review. Energy Convers. Manage. 2012;63:138–148. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gan S., Ng H.K., Ho W.W.S. Advances in ultrasound-assisted transesterification for biodiesel production. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016;100:553–563. doi: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2016.02.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.P.A. Oliveira, R.M. Baesso, G.C. Moraes, A.V. Alvarenga, R.P.B. Costa-Félix, Ultrasound Methods for Biodiesel Production and Analysis. In: Biernat, K. Biofuels – State of Development. 1ed.London: InTech. 2018. Chapter 7, p.121-148. DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.74303.

- 14.Luo J., Fang Z., Smith R.L., Jr. Ultrasound-enhanced conversion of biomass to biofuels. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2014;41:56–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pecs.2013.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yin X., Zhang X., Wan M., Duan X., You Q., Zhang J., Li S. Intensification of biodiesel production using dual-frequency counter current pulsed ultrasound. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;37:136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thanh L.T., Okitsu K., Maeda Y., Bandow H. Ultrasound assisted production of fatty acid methyl esters from transesterification of triglycerides with methanol in the presence of KOH catalyst: optimization, mechanism and kinetics. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014;21(2):467–471. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Babajide O., Petrik L., Amigun B., Ameer F. Low-cost feedstock conversion to biodiesel via ultrasound technology. Energies. 2009;3:1691–1703. doi: 10.3390/en3101691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ji J., Wang J., Li Y., Yu Y., Xu Z. Preparation of biodiesel with the help of ultrasonic and hydrodynamic cavitation. Ultrasonics. 2006;44:e411–e414. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choedkiatsakul I., Ngaosuwan K., Cravotto G., Assabumrungrat S. Biodiesel production from palm oil using combined mechanical stirred and ultrasonic reactor. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014;21:1585–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2013.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manickam S., Narasimha V., Arigela D., Gogate P.R. Intensification of synthesis of biodiesel from palm oil using multiple frequency ultrasonic flow cell. Fuel Process. Technol. 2014;128:388–393. doi: 10.1016/j.fuproc.2014.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.J. Shin, et al., Effects of ultrasonification and mechanical stirring methods for the production of biodiesel from rapeseed oil. Korean J. Chem. Eng. v, 29(4), p. 460–463, 2012. DOI: 10.1007/s11814-011-0205-3.

- 22.Thanh L.T., Okitsu K., Sadanaga Y., Takenaka N., Maeda Y., Bandow H. Ultrasound-assisted production of biodiesel fuel from vegetable oils in a small scale circulation process. Bioresour. Technol. 2010;101(2):639–645. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Georgogianni K.G., Kontominas M.G., Pomonis P.J., Avlonitis D., Gergis V. Conventional and in situ transesterification of sunflower seed oil for the production of biodiesel. Fuel Process. Technol. 2008;89(5):503–509. doi: 10.1016/j.fuproc.2007.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hingu S.M., Gogate P.R., Rathod V.K. Synthesis of biodiesel from waste cooking oil using sonochemical reactors. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2010;17(5):827–832. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maghami M., Sadrameli S.M., Ghobadian B. Production of biodiesel from fishmeal plant waste oil using ultrasonic and conventional methods. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2015;75:575–579. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan S.X., Lim S., Ong H.C., Pang Y.L. State of the art review on development of ultrasound-assisted catalytic transesterification process for biodiesel production. Fuel. 2019;235:886–907. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2018.08.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poosumas J., Ngaosuwan K., Quitain A.T., Assabumrungrat S. Role of ultrasonic irradiation on transesterification of palm oil using calcium oxide as a solid base catalyst. Energy Convers. Manage. 2016;120:62–70. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakayama R., Imai M., Woodley J.M. Ultrasound-assisted production of biodiesel FAME from rapeseed oil in a novel two-compartment reactor. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2017;92(3):657–665. doi: 10.1002/jctb.2017.92.issue-310.1002/jctb.5047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo W., Li H., Ji G., Zhang G. Ultrasound-assisted production of biodiesel from soybean oil using Brønsted acidic ionic liquid as catalyst. Bioresour. Technol. 2012;125:332–334. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.08.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laesecke A., Fortin T.J., Splett J.D. Density, speed of sound, and viscosity measurements of reference materials for biofuels. Energy Fuels. 2012;26:1844–1861. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baêsso R.M., Oliveira P.A., Morais G.C., Alvarenga A.V., Costa-Félix R.P.B. Ultrasonic parameter measurement as a means of assessing the quality of biodiesel production. Energies. 2019;241:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2018.12.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.J.A. Gallego-Juárez, F.J. Fuchs, Power ultrasonics: applications of high-intensity ultrasound, Chapter 19 (577-609) , Ed.1, 2015. DOI: 10.1016/B9781-78242-028-6.00019-3.

- 33.Ashokkumar M., Hodnett M., Zeqiri B., Grieser F., Price G.J. Acoustic emission spectra from 515 kHz cavitation in aqueous solutions containing surface active solutes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129(8):2250–2258. doi: 10.1021/ja067960r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stavarache C., Vinatoru M., Nishimura R., Maeda Y. Fatty acids methyl esters from vegetable oil by means of ultrasonic energy. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2005;12(5):367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferreira J.R.L., Costa-Félix R.P.B. Comparing ultrasound and mechanical steering in a biodiesel production process. Physics Procedia. 2015;70:1066–1069. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aghbashlo M., Tabatabaei M., Hosseinpourl S., Hosseini S.S., Ghaffari A., Khounani Z., Mohammadi P. Development and evaluation of a novel low power, high frequency piezoelectric-based ultrasonic reactor for intensifying the transesterification reaction. Biofuel Res. J. 2016;12:528–535. doi: 10.18331/BRJ2016.3.4.7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aghbashlo M., Hosseinpour S., Tabatabaei M., Dadak A. Fuzzy modeling and optimization of the synthesis of biodiesel from waste cooking oil (WCO) by a low power, high frequency piezo-ultrasonic reactor. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015;27:54–61. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oliveira P.A., Baesso R.M., Moraes G.C., Alvarenga A.V., Costa-Félix R.P.B. Biofuels – State of Development, Krzysztof Biernat. IntechOpen; 2018. Ultrasound methods for biodiesel production and analysis. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.T. Kimura, et al., Standardization of ultrasonic power for sonochemical reaction. Ultrasonics Sonochem., 3, S157–S161, 1996. DOI: 10.1016/S1350-4177(96)00021-1.

- 40.IEC 61161:2013, Ultrasonics – Power measurement – Radiation force balances and performance requirements, International Electrotechnical Commission, Geneva, Switzerland, 97pp.

- 41.Koda S., Kimura T., Kondo T., Mitome H. A standard method to calibrate sonochemical efficiency of an individual reaction system. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2003;10(3):149–156. doi: 10.1016/S1350-4177(03)00084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.J. Haller, C. Koch, R.P.B. Costa-Felix, P.K. Dubey, G. Durando, YT. Kim, M. Yoshioka, Final report on key comparison CCAUV.U-K3.1. Metrologia, vol. 53, Technical Supplement, 09002, 2016.

- 43.P.A. Oliveira, A.V. Alvarenga, R.P.B. Costa-Felix, Ultrasonic Output Power Measurement According to IEC 61161:2013. In: Costa-Felix R., Machado J., Alvarenga A. (eds) XXVI Brazilian Congress on Biomedical Engineering. IFMBE Proceedings, vol 70/1. Springer, Singapore. DOI: 10.1007/978-981-13-2119-1_133.

- 44.Verma P., Sharma M.P. Review of process parameters for biodiesel production from different feedstocks. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016;62:1063–1071. [Google Scholar]

- 45.EN 14103:2003 . European Committee for Standardization; Brussels: 2003. Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAME) – Determination of Ester and Linolenic Acid Methyl Esters Contents. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knothe G. Monitoring a progressing transesterification reaction by fiber optic near infrared spectroscopy with correlation to 1H Nuclear Magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2000;77(5):489–493. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gelbard G. 1H nuclear magnetic resonance determination of the yield of the transesterification of rapeseed oil with methanol. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1995;72:1239–1241. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coral N., Rodrigues E., Rumjanek V., Zamian J.R., da Rocha Filho G.N., da Costa C.E.F. Soybean biodiesel methyl esters, free glycerin and acid number quantification by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2012:69–71. doi: 10.1002/mrc.3913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.P. Poonpun, W.T. Jewell, Analysis of the cost per kilowatt hour to store electricity. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers., 23, (2), 2008. DOI: 10.1109/TEC.2007.914157.

- 50.Baesso R.M., Oliveira P.A., Morais G.C., Alvarenga A.V., Costa-Félix R.P.B. Using ultrasonic velocity for monitoring and analysing biodiesel production. Fuel. 2018;226:389–399. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2018.04.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Figueiredo M.-K., Alvarenga A.V., Costa-Félix R.P.B. Ultrasonic attenuation and sound velocity assessment for mixtures of gasoline and organic compounds. Fuel. 2017;191:170–175. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zabala S., Arzamendi G., Reyero I., Gandía L.M. Monitoring of the methanolysis reaction for biodiesel production by off-line and on-line refractive index and speed of sound measurements. Fuel. 2014;121:157–164. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oliveira P.A., Silva R.M.B., Morais G.C., Alvarenga A.V., Félix R. Speed of sound as a function of temperature for ultrasonic propagation in soybean oil. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2016;733:012040. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/733/1/012040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.JCGM, 2008, Evaluation of Measurement Data – Guide of the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurements, JCGM 100:2008.

- 55.Steele A.G., Douglas R.J. Extending En for measurement science. Metrologia. 2006;43(4):S235–S243. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chatfield C. Chapmal & Hall; 1992. Statistics for Technology – A Course in Applied Statistics; p. 381. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Y., Li S. Acoustical scattering cross section of gas bubbles under dual-frequency acoustic excitation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015;26:437–444. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fan X., Wang X., Chen F. Ultrasonically assisted production of biodiesel from crude cottonseed oil. Int. J. Green Energy. 2010;7(2):117–127. doi: 10.1080/15435071003673419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luo J., Fang Z., Smith R.L. Ultrasound-enhanced conversion of biomass to biofuels. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2014;41:56–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pecs.2013.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Daramola M.O., Mtshali K., Senokoane L., Fayemiwo O.M. Influence of operating variables on the transesterification of waste cooking oil to biodiesel over sodium silicate catalyst: a statistical approach. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 2016;10(5):675–684. doi: 10.1016/j.jtusci.2015.07.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xiao Y., Gao L., Xiao G., Lv J. Kinetics of the transesterification reaction catalyzed by solid base in a fixed-bed reactor. Energy Fuels. 2010;24(11):5829–5833. doi: 10.1021/ef100966t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bhangu S.K., Gupta S., Ashokkumar M. Ultrasonic enhancement of lipase-catalysed transesterification for biodiesel synthesis. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;34:305–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.