Abstract

Leishmaniasis is a parasitic disease considered an endemic public health problem in developing countries, where it is a reportable disease. Isolated oral manifestation is rare, and its clinical manifestations are variable. In this paper we describe an unusual case of an immunocompetent patient, 57-year-old man with a painless reddish submucosal nodule located on the tongue dorsum. Microscopical analysis showed chronic inflammatory infiltrate with macrophages containing leishmania in cytoplasmic vacuoles. PCR assays confirmed the diagnosis and patient was treated with meglumine antimoniate for 30 days. Absence of the parasite was confirmed by PCR. Thirteen years after treatment, a scar fibrosis persisted on the tongue dorsum. The case reported reveals that leishmaniasis should be considered in the diagnosis of tongue nodules in immunocompetent patients.

Keywords: Leishmaniasis, Oral mucosa, Tongue nodule, Oral diagnosis, Scar fibrosis, Meglumine antimoniate

Introduction

Considered one of the world’s most neglected diseases, American tegumentary leishmaniasis affects mainly poor and developing countries [1]. Leishmaniasis is caused by a protozoon of the genus Leishmania, transmitted to humans by sandfly vectors of the genus Phlebotomus or Lutzomyia [2–5]. Currently, more than 1 billion people are considered at risk of contracting leishmaniasis, and some 1 million new cases occur yearly [6]. Leishmaniasis in Latin America has been described in at least 12 countries, with 76% of cases occurring in Brazil, where is a reportable disease [7, 8].

There are at least 20 species of Leishmania that can affect humans, and these are usually divided according to their geographical location [9]. They have been denominated the Old World and New World types and may use different vectors as reservoirs [6, 10, 11]. Old World leishmaniasis is frequently found in open semiarid areas or deserts in some parts of Asia, Middle East, Africa, and southern Europe. New World leishmaniasis is usually found in tropical areas, such as forests, specifically in some parts of Mexico and Central and South America [6, 9, 12, 13]. The clinical manifestations of leishmaniasis can be divided into cutaneous, mucocutaneous, visceral leishmaniasis, and post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis, and are determined by the parasite species and host immune response [12, 13]. In Central and South America the Leishmania Viannia braziliensis (LVB) is the subtype most commonly associated with cases of mucocutaneous lesions [13, 14]. The term ‘mucocutaneous leishmaniasis’ is applied only to the New World disease, of which the majority of cases are reported in Bolivia, Brazil and Peru [6, 10]. Oral mucosal involvement is considered rare [2, 14, 15], and occurs in only 3–5% of patients infected with LVB. Although any anatomical site of the oral mucosa may be affected, typically the most frequent clinical presentation includes ulceration in the hard or soft palate. The lesions can present as exophytic nodules or indurated lesions that can mimic a malignant lesion [3, 14]. Pain, odynophagia and dysphagia may be associated with lesions.

In mucosal leishmaniasis, detection of the parasite is difficult and in the majority of cases the diagnosis is made based on the results of the Montenegro skin test, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), serologic tests, and histopathology findings [16, 17]. Histological diagnosis is based on the observation of amastigotes in mucosal samples stained with Giemsa or hematoxylin and eosin, in addition to subepithelial non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammatory reaction with lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes as the predominant cells [3, 18]. Immunohistochemistry is a useful technique to confirm the diagnosis because the histopathological findings generally show nonspecific chronic inflammation or granulomatous reaction with only a few parasites [3]. PCR is another helpful tool for diagnosing leishmaniasis. The technique is a highly sensitive, fast, and efficient method even with a low DNA/RNA load. PCR amplifies specific sequences of Leishmania DNA/RNA by specific primers providing a reliable identification of leishmania [19, 20]. In this paper we report a rare case of leishmaniasis with oral primary manifestation diagnosed by PCR in an immunocompetent patient.

Case Report

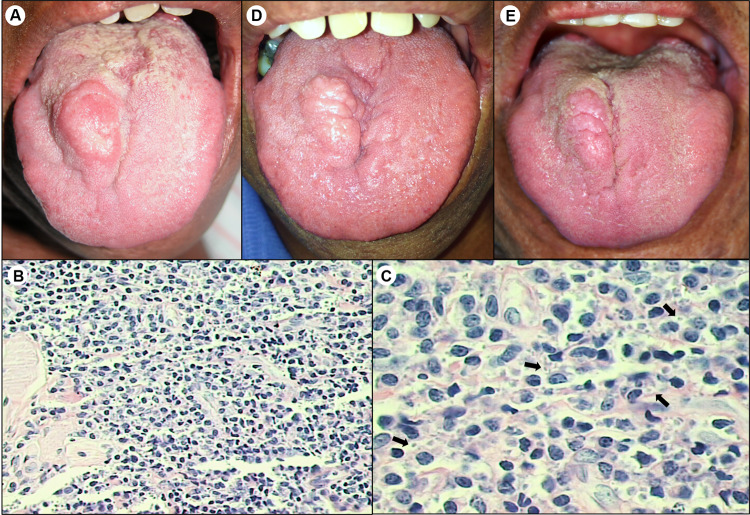

The patient, a 57-year-old man was referred to our service complaining of a lesion on the tongue that had evolved in one month. Past medical history was significant for hypertension. Oral examination revealed an indurated and ulcerated nodule on the right side of tongue dorsum, measuring 3 × 2 cm, painless, with sessile base and reddish color. (Fig. 1a). No skin lesions were observed. Differential diagnosis included leiomyoma, granular cell tumor, and granulomatous infections (tuberculosis, leishmaniasis, and sarcoidosis). Complete blood count and coagulogram showed no abnormality. An incisional biopsy was performed under local anesthesia and histopathological examination showed a dense subepithelial inflammatory reaction with lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages containing scarce round-shaped leishmania-like intracytoplasmic inclusions (Fig. 1b, c), suggesting the diagnosis of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. To confirm the diagnosis of leishmaniasis, DNA extraction was performed from paraffin-embedded tissue, and subjected to PCR assays with Leishmania-specific PCR primers to the SSU RNA gene. The final fragment obtained was cloned and four clones were sequenced. The nucleotide sequences were compared with the sequences SSU rDNA standard for Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis (5′-GAATTGCCCATAGAATAGCA-3′), Leishmania (Leishmania) chagasi (5′-GAATTGCCCATAGGATAGCA-3′), Leishmania (Viannia) sp (5′-GAATTGTCCATAGGATAGCA-3′). The four clones resulted in the same sequence that was identical to Leishmania (Viannia) sp sequence, confirming the positivity for LVB. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) PCR assays were used for detection among Leishmania (Viannia) subtypes, which were negative, probably because there were few parasites in the sample. Serological tests were negative for HIV and Syphilis. The patient was treated with meglumine antimoniate (20 mg/kg/day) by daily intramuscular administration (two ampoules) for 30 days. Three weeks after beginning the medical treatment, clinical examination revealed a slight reduction in the size of tongue lesion. The complete blood count and results of the kidney and liver function tests showed no abnormalities during the treatment with pentavalent antimonial. Three months after the treatment, the oral lesion remained static without a reduction in size. A biopsy was performed and microscopy analysis revealed the presence of necrotic tissue. Fresh tissue was also collected and PCR assay was negative for detecting leishmania DNA. Seven years after treatment, a painless nodular fibrous tissue scar persisted on the tongue dorsum (Fig. 1d). During the follow-up period it was proposed to the patient performing a surgical plasty to remove the scar fibrosis tissue, however he did not agree to undergoing the surgery. In ten- and thirteen-year follow-up patient had good general health and fibrous nodule on the tongue dorsum was slightly smaller than it had been in previous visits (Fig. 1d, e).

Fig. 1.

Clinical and histopathological presentation of Leishmaniasis in immunocompetent patient. a Ulcerated nodule on right side of tongue dorsum. b Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed intense inflammatory infiltration by mononuclear cells (× 100). c Inflammatory infiltrate had predominance of macrophages and plasma cells. Arrows indicate presence of macrophages containing leishmania in cytoplasmic vacuoles (H&E, × 400). d Clinical appearance 7 years after treatment with meglumine antimoniate showing permanence of fibrous scar tissue at site of injury. e Thirteen-year follow-up revealed patient with good general health and reduction of fibrous scar nodule

Discussion

Primary mucosal involvement by leishmaniasis is rare, since the mucosal lesion may normally occur months or years after the onset of the primary cutaneous lesion [14, 21]. In this report, the patient had no skin lesions preceding or accompanying the oral manifestation of infection. This feature led to this case differing particularly from most cases of mucocutaneous lesions caused by LVB. A striking feature of this disease is that the skin lesions usually precede or accompany the development of oral and upper respiratory tract lesions, as a result of hematogenous or lymphatic spread of amastigotes from the skin to mucous membranes.

Individuals who live in endemic locations and regional travelers (such as ecotourists, missionaries, and soldiers) are considered a population at risk for infection with leishmaniasis [12, 21]. A detailed anamnesis is crucial for the diagnosis of leishmaniasis, and must take into account the systemic health of the patient and possible contact with endemic areas [22]. In the present case, the patient was a resident of an endemic area for leishmaniasis in the state of São Paulo – Brazil. Studies have shown an increase in the incidence of leishmaniasis in HIV-positive patients, probably due to a their compromised T-cell immune response [23]. This is a factor that should be considered during the diagnosis; however, our patient had no HIV infection and was not immunosuppressed by other causes.

Oral lesions of leishmaniasis usually appears in the form of granulomatous ulcers or vegetative lesions, with peripheral mucosa showing indurated swelling of hyperemic surface [2]. These characteristics are in agreement with those observed in our case, in which a painless exophytic nodule appeared on the patient’s tongue dorsum. The clinical form of leishmaniasis in oral mucosa varies considerably, and may mimic other oral lesions [21]. The clinicopathological differential diagnosis includes fungal infections (e.g., paracoccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis and cryptococcosis), tuberculosis, hanseniasis, sarcoidosis, lymphoma, and Wegener’s disease, among other disorders [24]. The clinical and histopathological similarity makes the diagnosis of leishmaniasis a challenging task [25]. The most common histopathological features of leishmaniasis are ulceration with granulation tissue, multinucleated giant cells, lymphocyte aggregates and intense perineural and muscular inflammatory infiltrate [3]. These microscopical findings can also be observed in histoplasmosis and paracoccidioidomycosis infections [3, 26, 27]. The diagnosis of leishmaniasis can be difficult due to the small number of amastigotes, so that the use of more sensitive techniques is required in order to identify the Leishmania [3, 19, 22]. In our case, microscopic analysis allowed direct visualization of the amastigotes and PCR assay confirmed the infection by L (Viannia) braziliensis. We agree with Sanches Romero et al. [19], that for a more precise diagnosis it is desirable to perform PCR assays.

The clinical course of the mucosal disease is dependent on a combination of host cell-mediated immunity and parasite virulence, although the factors that determine which patients will develop oral mucosal leishmaniasis remain uncertain [11, 28]. The Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization recommends pentavalent antimony and its derivatives, sodium stibogluconate and meglumine antimoniate for the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis, which have demonstrated better results in comparison with other drugs [6, 18]. It is now known that drugs such as pentamidine and amphotericin B may be equally effective for the treatment of mucosal leishmaniasis [29–31]. The treatment of our patient with meglumine antimoniate for one month induced cure of infection and regression of the ulcerated areas. However, a fibrous scar tissue persisted at the site of the injury. Although little is known about the healing process of leishmaniasis lesions, the case reported here revealed that even after the treatment of mucosal leishmaniasis, fibrosis scar tissue without the presence of the parasite may remain at the site of the primary lesion, In the case of skin lesions, healing will depend on establishing a specific rapid and intense inflammatory response against the parasite [32]. Early diagnosis of the disease with rapid institution of treatment may prevent the parasite from spreading. The case reported also showed that although oral manifestation of leishmaniasis in immunocompetent patients is rare, it may be the first or only clinical finding and should be considered as a differential diagnosis of tongue lesions.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dra Lucile Maria Floeter-Winter from Department of Physiology, Institute of Biosciences, University of São Paulo (USP), for performing the PCR assays.

Funding

No funding obtained.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Okwor I, Uzonna J. Social and economic burden of human leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;94:489–493. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santos CR, Tuon FF, Cieslinski J, de Souza RM, Imamura R, Amato VS. Comparative study on liposomal amphotericin B and other therapies in the treatment of mucosal leishmaniasis:A15-yearretrospectivecohortstudy. PLoS ONE. 2018;14:23–31. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daneshbod Y, Oryan A, Davarmanesh M, Shirian S, Negahban S, Aledavood A, et al. Clinical, histopathologic, and cytologic diagnosis of mucosal leishmaniasis and literature review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:478–482. doi: 10.1043/2010-0069-OA.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Motta ACF, Lopes MA, Ito FA, Carlos-Bregni R, De Almeida OP, Roselino AM. Oral leishmaniasis: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. Oral Dis. 2007;13:335–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2006.01296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Almeida TFA, da Silveira EM, dos Santos CRR, León JE, Mesquita ATM. Exclusive primary lesion of oral leishmaniasis with immunohistochemical diagnosis. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:533–537. doi: 10.1007/s12105-016-0732-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Leishmaniasis. World Health Org Fact Sheet. World Heal. Organ. 2020. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs375/en/.

- 7.Pan American Health Organization. Leishmaniasis: Epidemiological Report in the Americas. Washington, DC: PAHO. 2019. p. 2–5. http://iris.paho.org/xmlui/handle/123456789/50505.

- 8.Brazil MS. Tegumentary Leishmaniasis (TL): what it is, causes, symptoms, treatment, diagnosis and prevention. Tegumentary Leishmaniasis what it is, causes, symptoms, Treat diagnosis Prev. 2019. p. 4. http://www.saude.gov.br/saude-de-a-z/leishmaniose-tegumentar.

- 9.Akhoundi M, Kuhls K, Cannet A, Votýpka J, Marty P, Delaunay P, et al. A historical overview of the classification, evolution, and dispersion of leishmania parasites and sandflies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Handler MZ, Patel PA, Kapila R, Al-Qubati Y, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis: clinical perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:897–908. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goto H, Lauletta Lindoso JA. Cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2012;26:293–307. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nadler C, Enk CD, Leon GT, Samuni Y, Maly A, Czerninski R. Diagnosis and management of oral leishmaniasis—case series and literature review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;72:927–934. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2013.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teemul TA, Giles-Lima M, Williams J, Lester SE. Laryngeal leishmaniasis: case report of a rare infection. Head Neck. 2013 doi: 10.1002/hed.23141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.da Costa DC, Palmeiro MRMJ. Oral manifestations in the American tegumentary leishmaniasis. PLoS ONE. 2015 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garg S, Tripathi R, Tripathi K. Oral mucosal involvement in visceral leishmaniasis. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2013;6:249–250. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(13)60034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palmeiro MR, Rosalino CMV, Quintella LP, Morgado FN, da Costa Martins AC, Moreira J, et al. Gingival leishmaniasis in an HIV-negative patient. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endodontol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marsden PD. Mucosal leishmaniasis (“espundia” escomel, 1911) Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1986;80:859–876. doi: 10.1016/00359203(86)90243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strazzulla A, Cocuzza S, Pinzone MR, Postorino MC, Cosentino S, Serra A, et al. Mucosal leishmaniasis: an underestimated presentation of a neglected disease. Biomed Res Int. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/805108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sánchez-Romero C, Júnior HM, da Matta VLR, Freitas LM, Soares CM, Mariano FV, et al. Immunohistochemical and molecular diagnosis of mucocutaneous and mucosal leishmaniasis. Int J Surg Pathol. 2020;28:138–145. doi: 10.1177/1066896919876706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deepachandi B, Weerasinghe S, Soysa P, Karunaweera N, Siriwardana Y. A highly sensitive modified nested PCR to enhance case detection in leishmaniasis. BMC Infect Dis. 2019 doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4180-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mignogna MD, Celentano A, Leuci S, Cascone M, Adamo D, Ruoppo E, et al. Mucosal leishmaniasis with primary oral involvement: a case series and a review of the literature. Oral Dis. 2015;21:e70–e78. doi: 10.1111/odi.12268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bogdan C. Leishmaniasis in rheumatology, haematology and oncology: epidemiological, immunological and clinical aspects and caveats. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akuffo H, Costa C, van Griensven J, Burza S, Moreno J, Herrero M. Newinsights into leishmaniasis in the immunosuppressed. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcíade Marcos JA, Dean Ferrer A, Alamillos Granados F, Ruiz Masera JJ, Cortés Rodríguez B, Vidal Jiménez A, et al. Localized leishmaniasis of the oral mucosa. A report of three cases. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pellicioli ACA, Martins MAT, Filho MSA, Rados PV, Martins MD. Leishmaniasis with oral mucosa involvement. Gerodontology. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2011.00512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vicente CR, Falqueto A. Differentiation of mucosal lesions in mucocutaneous leishmaniasis and paracoccidioidomycosis. PLoS ONE. 2018 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Arruda JAA, Schuch LF, Abreu LG, Silva LVO, Mosconi C, Monteiro JLGC, et al. A multicentre study of oral paracoccidioidomycosis: analysis of 320 cases and literature review. Oral Dis. 2018;24:1492–1502. doi: 10.1111/odi.12925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mazumder SA, Pandey S, Brewer SC, Baselski VS, Weina PJ, Land MA, et al. Lingual leishmaniasis complicating visceral disease. J Travel Med. 2010;17:212–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2010.00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amato VS, Tuon FF, Bacha HA, Neto VA, Nicodemo AC. Mucosal leishmaniasis. Current scenario and prospects for treatment. Acta Trop. 2008;105:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization/Pan American Health Organization. Leishmaniasis in the Americas: treatment recommendation. 2018. p. 60. http://iris.paho.org/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/7704/9789275117521_eng.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y.

- 31.Santos CR, Tuon FF, Cieslinski J, de Souza RM, Imamura R, Amato VS. Comparative study on liposomal amphotericin B and other therapies in the treatment of mucosal leishmaniasis: a 15-year retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2018 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brazil. Ministry of Health. Secretariat of Health Surveillance. Department of Surveillance of Communicable Diseases. Tegumentary leishmaniasis surveillance manual. 2017. p. 191. http://www.dive.sc.gov.br/conteudos/publicacoes/17_0093_M_e_C.pdf.