Abstract

Introduction and methods

Dynamic fluorescence quenching is a technique that may overcome some of the limitations associated with measurement of tissue partial oxygen tension (PO2). We compared this technique with a polarographic Eppendorf needle electrode method using a saline tonometer in which the PO2 could be controlled. We also tested the fluorescence quenching system in a rodent model of skeletal muscle ischemiahypoxia.

Results

Both systems measured PO2 accurately in the tonometer, and there was excellent correlation between them (r2 = 0.99). The polarographic system exhibited proportional bias that was not evident with the fluorescence method. In vivo, the fluorescence quenching technique provided a readily recordable signal that varied as expected.

Discussion

Measurement of tissue PO2 using fluorescence quenching is at least as accurate as measurement using the Eppendorf needle electrode in vitro, and may prove useful in vivo for assessment of tissue oxygenation.

Keywords: clinical measurement methodology, fiberoptic measurement, fluorescence quenching, ischemia, Stern–Volmer, tissue oxygenation

Introduction

Accurate measurement of PO2 in biologic tissues has been of interest to both researchers and clinicians for many years [1]. For basic scientists measurement of PO2 provides insight into the complexities of oxygen flux at the tissue level, whereas for clinicians it moves the monitoring window a step closer to the cell. PO2 monitoring has been exploited most effectively by radiation oncologists, who have used intratumoral PO2 measurements to plan and guide radiotherapy [2]. Many articles in the anesthesia and critical care literature report the application of different technologies designed to measure tissue PO2[1,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14], but the clinical use of PO2 measurement has largely been limited to assessment of brain tissue [15,16].

Existing technologies for measuring tissue PO2 are either too expensive for everyday clinical use [14] or are based on polarographic principles [17], meaning that oxygen is consumed in the measurement process. In time this oxygen consumption affects the signal itself, and this effect persists as tissue PO2 decreases, perhaps making polarographic devices less suitable for detection of tissue hypoxia. We hypothesized that a PO2 measurement technique based on dynamic fluorescence quenching would provide a way to overcome the limitations of the current polarographic technique. We report here a head-to-head bench comparison of PO2 measurement using polarography versus measurement using dynamic fluorescence quenching. We also present preliminary data from an animal model of tissue ischemia and hypoxia that provide evidence of a potentially useful application of fluorescence quenching as a monitor of tissue integrity.

Methods

Tonometry apparatus

We constructed an equilibration tonometer (from a sealed, inverted 50-ml syringe part filled with 0.9% saline and a length of tubing ending in a diffusing stone) and immersed it in a water bath maintained at a constant temperature (37°C). We then connected the tubing to a low pressure oxygen/ nitrogen gas mixer, such that gas bubbled through the stone and saline solution. A loose cover maintained the gas mixture above the saline but was not so tight as to cause the pressure to rise above atmospheric pressure. In an earlier experiment we determined that the PO2 in the saline solution equilibrated within 90 s (unpublished observations). An oxygen fluorescence quenching probe (FOXY; Ocean Optics Inc., Dunedin, FL, USA), electronic thermometer, and polaro-graphic (Eppendorf Instruments, Hamburg, Germany) needle electrode were inserted through the tonometer cover. The oxygen concentration of the inflow gas was measured in-line with a conventional fuel cell oxygen analyzer and this was used to calculate a predicted PO2 (PO2 pred) in the saline according to the following equation:

PO2 pred = FiO2 × (PB - PH2O) (1)

Where FiO2 is the oxygen concentration in the inflow gas, PB is the atmospheric pressure recorded in the laboratory on the day of the experiment, and PH2O is the water vapor pressure.

Dynamic fluorescence quenching optode

The optode consists of a 200-μm aluminum-coated, ruthenium-tipped glass fiber with a medical-grade silicone covering on the tip. The response time of the device is about 45 s in a liquid medium. The light source is a dedicated light-emitting diode that emits pure blue light at a wavelength of 470 nm. When excited the ruthenium emits light (fluoresces) with peak intensity at 600 nm that is quenched by the presence of oxygen. The fluorescence signal is then converted to a PO2 value by specialized software (OOISENSORS; Ocean Optics Inc.).

Polarographic needle electrode

This system has been described in detail elsewhere [18]. Briefly, it comprises a needle electrode mounted on a stepping motor that sequentially advances and then retracts the needle tip. This allows the system to create a histogram of PO2 recordings from the tissue of interest. The current pro-duced by the needle electrode is linearly related to the PO2 value in the medium surrounding the electrode tip.

Bench comparison experiment

Calibration

For the fluorescence quenching system we used a 1% weight/volume solution of sodium sulfite as zero PO2 for the low calibration standard. This chemical does not affect the optical sensing system. Sterile water in equilibration with laboratory air was used as a high calibration standard, using equation 1 with FiO2 set to 0.21. Although it is theoretically reasonable to calibrate the sensor in one medium (e.g. gaseous) and then measure PO2 in another (e.g. liquid), we have no experimental data to support this.

The needle electrode was calibrated according to the manufacturer's instructions [19]. As described above, our laboratory bench tonometer was kept at a constant temperature of 37 ± 1°C. It was thus not necessary to correct for temperature in this experiment.

Measurement protocol

Once both measurement systems had been calibrated and inserted into the saline tonometer, the system was allowed to come to equilibrium for 5 min. We then varied the concentration of oxygen in the inflow gas so that the PO2 in the saline would rise or fall. After each change, we waited 3 min for the system to equilibrate before recording the PO2 value from each device and the PO2 pred value from the inflow gas. We repeated these steps to record 58 consecutive data triplets. Finally, we re-measured the low and high calibration solutions to assess drift in PO2 values across the duration of the experiment.

In vivo application

Animal model

The experimental protocol was approved by The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Animal Care and Use Committee. Male outbred Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 3) weighing 410–440 g were anesthetized using inhaled isoflu-rane in a mixture of 35% oxygen and 65% nitrogen. Each animal was placed on a homeothermic blanket (Harvard Apparatus Inc., Holliston, MA, USA); the trachea was then intubated (using a modified neonatal laryngoscope and 14-gauge cannula) and the lungs were mechanically ventilated. A small midline laparotomy was performed to allow for placement of a vascular clip on the infrarenal aorta. Cannulae (PE 20; Harvard Apparatus Inc.) were placed in the left femoral artery and vein to allow measurement of arterial pressure (MLT-1050 transducer; AD Instruments, Mountain View, CA, USA) and administration of 1 ml/100 g per h 0.9% saline. Neuromuscular blockade was achieved using 0.2 mg/kg pan-curonium bromide by intravenous bolus, supplemented later as needed. Finally, the dynamic fluorescence quenching optode was attached to a micromanipulator and inserted (via a 19-gauge needle) percutaneously into the right hind limb skeletal muscle bed.

Experimental protocol

Once surgery was complete, the animal was allowed to recover for 20 min before the experiment began. Following an initial baseline period of 5 min the aorta was cross-clamped for 30 min, after which the vascular clip was removed. After a 20-min period of reperfusion, the animal was ventilated with 100% nitrogen for 90 s and then the FiO2 was returned to 0.35. After a further period of ventilation, the animal was killed by isoflurane overdose and exsanguination via the arterial line.

Data analysis

To identify relationships between the two measurement techniques and PO2 pred, we calculated product–moment correlation statistics. To investigate differences between the two systems and PO2 pred, we constructed Bland–Altman plots [20]. For the animal data we performed one-way analysis of variance with Newman-Keuls post-testing to detect differences within groups. Analyses were performed in Excel 2000 (Microsoft Inc., Redmond, WA, USA) using the Analyse-It statistical add-in (Analyse-It Software Ltd, Leeds, UK) and GraphPad Prism 3.02 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Bench comparison data

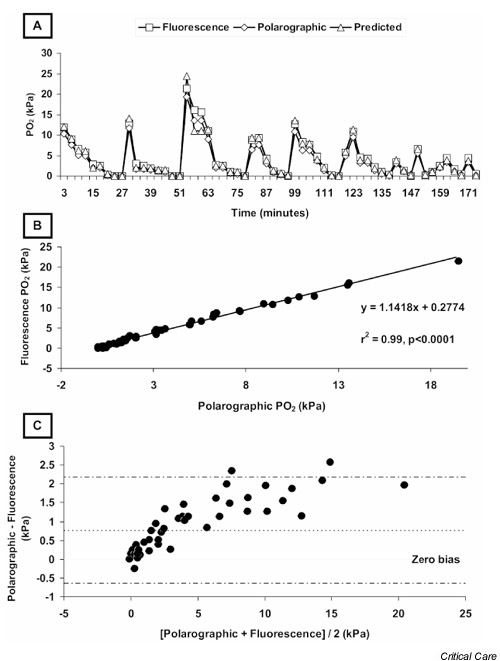

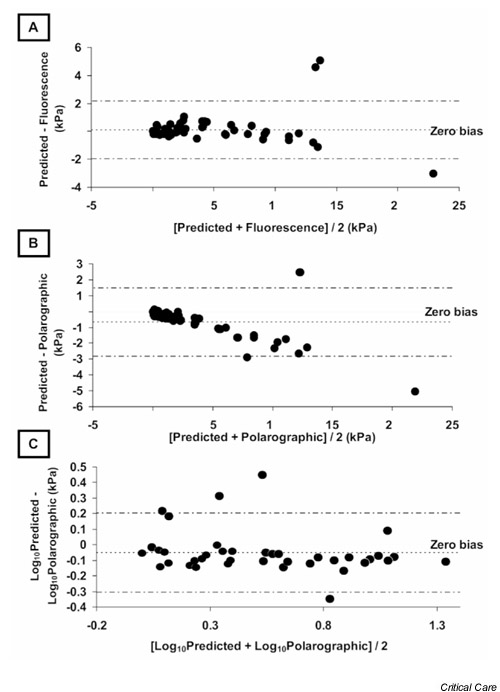

Fig. 1A shows the changes in PO2 pred, fluorescence quenching PO2, and polarographic PO2 values plotted against time. There was remarkable agreement between the data generated by the quenching technique and that generated by the polarographic technique (r2 = 0.99, P < 0.0001; Fig. 1B), but this analysis hides a difference that only becomes apparent on consideration of the Bland–Altman plot of the two measurement techniques (Fig. 1C). Bias proportional to the magnitude of the signal was clearly evident, but it remained unclear which device was responsible for it. Plots of both techniques compared with PO2 pred revealed an apparent proportional bias in the polarographic data but not in the quenching data (Figs 2A and 2B). As suggested by Bland and Altman [20], log transformation (Fig. 2C) shows correction of the bias in the polarographic plot, suggesting that the error arose from the polarographic dataset. The fluorescence quenching system showed minimal drift across the course of the experiment (low points were 0.0 and 0.08 kPa and high points were 20.2 and 20.9 kPa at the start and finish, respectively). The polarographic system required recalibrating after approximately 30 data sets, so we were unable to measure the drift of the device.

Figure 1.

(A) Plot of fluorescence, polarographic and predicted partial oxygen tension (PO2) against time. (B) Correlation plot of polarographic and fluorescence measurement techniques. (C) Bland–Altman plot of polarographic and fluorescence techniques demonstrating proportional bias arising from one (or both) of the techniques.

Figure 2.

(A) Bland–Altman plot of fluorescence technique and predicted partial oxygen tension (PO2), demonstrating close limits of agreement and no systematic or proportional bias over the measurement range. (B) Bland–Altman plot of polarographic technique and predicted PO2 demonstrating clear proportional bias, which corrects with logarithmic transformation of the data (C).

In vivo data

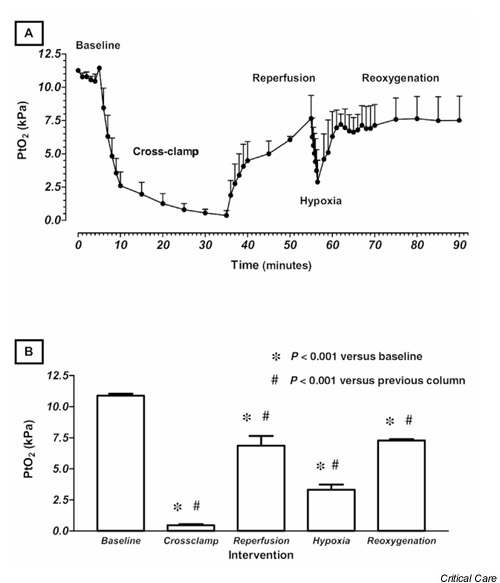

A plot of tissue PO2 against time is depicted in Fig. 3A. The baseline value of 11.2 kPa reflects the baseline FiO2 of 0.35 and is higher than resting values in similar in vivo studies that used 0.21 as their baseline FiO2 [21]. This is an important concept because arterial PO2 has a profound and incompletely understood effect on tissue PO2. The tissue PO2 fell very quickly after the aorta was cross-clamped, and it began to rise again when tissue perfusion was re-established. Soon after the animals breathed 100% nitrogen, the tissue PO2 fell sharply and rose again when oxygen was reintroduced into the inspired gas mixture. Fig. 3B shows the data presented by intervention. For this graph, the mean values of the last three data points before a change were taken to reflect that intervention.

Figure 3.

Data are expressed as means ± SEM from three animals. (A) Plot of skeletal muscle partial oxygen tension (PtO2) against time, showing clear reduction in signal during both ischemic (cross clamp) and hypoxic epochs. (B) PtO2 plotted by intervention. Significant differences were found between PtO2 values for each group and the baseline PtO2 value, and between each intervention group and the group immediately preceding it.

Discussion

There is increasing interest in the use of tissue PO2 as a monitor of critical illness [15,16,22,23,24]. The most favorable tissue in which to record this variable has yet to be determined, and candidates include the gut [25], subdermis [26], skeletal muscle [27], wound margins [11], brain [15], and bladder mucosa [28]. We demonstrated that dynamic fluorescence quenching is at least as accurate as the polaro-graphic system for measuring PO2.

The optical device used in this experiment measures PO2 using the principle of dynamic fluorescence quenching. As a triplet molecule, oxygen is able to quench efficiently the phosphorescence and fluorescence of certain luminophores, and it is this concept that underlies the principle used by optical systems such as ours to measure PO2. When an oxygen molecule collides with a fluorophore in its excited state, there is a non-radiative transfer of energy that leads to a reduction in the fluorescence displayed by the fluorophore. The PO2 value in the medium that contains the fluorophore is inversely proportional to the intensity of fluorescence exhibited. This relationship is described by the Stern–Volmer equation:

I0/I = 1 + k·PO2 (2)

where I0 is the fluorescence intensity recorded at zero oxygen tension, I is the intensity at oxygen tension P, and k is the Stern–Volmer constant. According to this equation, the relationship between PO2 and signal intensity is linear, but this assumption is only valid for lower values of PO2 (below approximately 20 kPa). For partial pressures greater than 20 kPa, it is necessary to employ a second-order polynomial algorithm:

I0/I = 1 + k1(PO2) + k2(PO2)2 (3)

where I0 is the fluorescence intensity recorded at zero oxygen tension, I is the intensity at oxygen tension P, k1 is the first coefficient and k2 is the second coefficient. Sinaasappel and lnce [29] pointed out that oxygen is 10% less soluble in serum than in water [30], and thus recommended the use of concentration rather than tension as a unit of measurement for in vivo work. The solubility of oxygen in interstitial fluid (in the tissue milieu) is not known, and it is uncertain whether it differs from that of oxygen in water or serum. Even if it does, it is improbable that the solubility would differ from one type of tissue to the next because that would require a difference in the composition of the extracellular fluid, which is unlikely. Thus, the effect of any unmeasured differences in oxygen solubility would be (at most) to introduce a small systematic bias into the data. The intensity of the fluorescence signal increases as the PO2 decreases, and this is reflected by the increasing accuracy of optical systems at low PO2 levels. This feature of dynamic fluorescence quenching, coupled with the fact that it does not consume oxygen in the measurement process, makes it attractive for the detection and monitoring of hypoxia.

According to the manufacturer, the accuracy of the fluorescence quenching technique is affected by the calibration procedure, the resolution (random noise), and deviations from the Stern–Volmer relationship, which occur primarily at higher PO2 values. It is reasonable to assume that this technique would work in vivo, and our representative animal data, although limited, suggest that this approach is feasible and accurate, at least in skeletal muscle. Predictably, the tissue PO2 dropped during both the period of presumed ischemia (aortic cross-clamping) and hypoxia (FiO2 = 0.0), and we conclude from this that the fluorescence quenching method is able to detect changes in a biologically plausible signal.

The technique of oxygen measurement described here is at least as accurate as the accepted polarographic technique, is cheaper and more wieldy, does not consume oxygen, and may be combined with existing devices (such as a nasogas-tric tube) more easily. We believe that this approach is a useful addition to the available techniques and that it might allow more widespread use of tissue PO2 measurement, both as a marker of tissue integrity and an indicator of impending pathology. In vivo studies of fluorescence quenching PO2 measurement under different pathophysiologic conditions are currently underway in our laboratory.

We believe our data illustrate an important concept in the interpretation of method comparison studies. Reliance on the correlation coefficient alone may lead to the erroneous conclusion that there is no difference between the techniques [20]. Close correlation (with a high value for r2) merely identifies a close relationship between two variables. The method of Bland and Altman reveals differences between the two techniques, and we believe that close limits of agreement with a small overall bias should be characteristic features of a dataset that leads to a conclusion of no difference between the two methods under consideration. Our data revealed a proportional bias in the standard technique, and we were able to demonstrate this by comparing both techniques with a theoretical (but constant for each system) variable.

Competing interests

None declared.

Abbreviations

FiO2 = fractional inspired oxygen; PO2 = partial oxygen tension.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by Institutional Research Grants 4-3721202 and 1-8779701 to Dr Shaw. We gratefully acknowledge the help of Dr P. Dougherty, PhD, and the Office of Scientific Publications, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center with preparation of the manuscript. This work was presented in part at The American Society of Anesthesiolo-gists 2001 Annual Meeting, October 13–17 2001, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA.

References

- Levy JM, Simmons JA. A compact oxygen tension sensor. Med Biol Eng. 1972;10:121–122. doi: 10.1007/BF02474581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordsmark M. Direct measurements of tumor-tissue PO2: a way of selecting patients for hyperoxic treatment. Strahlenther Onkol. 1996;172(suppl 2):8–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kram HB, Shoemaker WC. Method for intraoperative assessment of organ perfusion and viability using a miniature oxygen sensor. Am J Surg. 1984;148:404–407. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(84)90482-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden BA, Sulonen J, Vannas A, Sweeney DF, Efron N. Direct in vivo measurement of corneal epithelial metabolic activity using a polarographic oxygen sensor. Ophthalm Res. 1985;17:168–173. doi: 10.1159/000265369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki C. First experimental results with the oxygen electrode as a local blood flow sensor in canine colon. Br J Surg. 1985;72:452–453. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800720616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiddian-Green RG, Baker S. Predictive value of the stomach wall pH for complications after cardiac operations: comparison with other monitoring. Crit Care Med. 1987;15:153–156. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198702000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunter JB. A buccal sensor for measuring arterial oxygen saturation. Anesth Analg. 1989;69:417–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefansson E, Peterson JI, Wang YH. Intraocular oxygen tension measured with a fiber-optic sensor in normal and diabetic dogs. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:H1127–H1133. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.4.H1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjortdal VE, Timmenga EJ, Kjolseth D, Brink Henriksen T, Stender Hansen E, Djurhuus JC, Gottrup F. Continuous direct tissue oxygen tension measurement: a new application for an intravascular oxygen sensor. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1991;80:8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golde AR, Mahoney JL. The oxygen optode: an improved method of assessing flap blood flow and viability. J Otolaryn-gol. 1994;23:138–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopf HW, Hunt TK. Comparison of Clark electrode and optode for measurement of tissue oxygen tension. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1994;345:841–847. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2468-7_110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell CC, Schultz SC, Burris DG, Drucker WR, Malcolm DS. Subcutaneous oxygen tension: a useful adjunct in assessment of perfusion status. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:867–873. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199505000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley BA, Parmley CL, Butler BD. Skeletal muscle PO2, PCO2, and pH in hemorrhage, shock, and resuscitation in dogs. J Trauma. 1998;44:119–127. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199801000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths JR, Robinson SP. The OxyLite: a fibre-optic oxygen sensor. Br J Radiol. 1999;72:627–630. doi: 10.1259/bjr.72.859.10624317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charbel FT, Du X, Hoffman WE, Ausman JI. Brain tissue PO2, PCO2, and pH during cerebral vasospasm. Surg Neurol. 2000;54:432–437. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(00)00340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman GJ, Hoffman WE, Rico C, Ripper R. Comparison of brain tissue and local cerebral venous gas tensions and pH. Neurol Res. 2000;22:642–644. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2000.11740734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubbers DW. Oxygen electrodes and optodes and their application in vivo. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1996;388:13–34. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-0333-6_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleckenstein W, Weiss C. A comparison of PO2 histograms from rabbit hind-limb muscles obtained by simultaneous measurements with hypodermic needle electrodes and with surface electrodes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1984;169:447–455. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-1188-1_39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppendorf Instruments Eppendorf PO2 Histograph Operating Manual: Program Version 25 Eppendorf Instruments: Hamburg, Germany; 1993. pp. 25–26.

- Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley BA, Butler BD. Comparison of skeletal muscle PO2, PCO2, and pH with gastric tonometric PCO2 and pH in hemorrhagic shock. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1869–1877. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199909000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegemund M, van Bommel J, Ince C. Assessment of regional tissue oxygenation. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25:1044–1060. doi: 10.1007/s001340051011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niehoff K, Barnikol WK. A new measuring device for non-invasive determination of oxygen partial pressure and oxygen conductance of the skin and other tissues. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;471:705–714. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4717-4_81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman WE, Charbel FT, Edelman G, Ausman JI. Thiopental and desflurane treatment for brain protection. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:1050–1053. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199811000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel HL, Nguyen HB, Shea-Donohue T, Aiton LA, Ratigan J, Malcolm DS. Diaspirin cross-linked hemoglobin is efficacious in gut resuscitation as measured by a GI tract optode. J Trauma. 1996;40:231–240. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199602000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney JD, Stotts NA, Goodson WH. Effects of dynamic exercise on subcutaneous oxygen tension and temperature. Res Nursing Health. 1995;18:97–104. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley BA, Ware DN, Marvin RG, Moore FA. Skeletal muscle pH, PCO2, and PO2 during resuscitation of severe hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma. 1998;45:633–636. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199809000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, Rosser D, Stidwill R. Bladder epithelial oxygen tension as a marker of organ perfusion. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand Suppl. 1995;107:77–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1995.tb04337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinaasappel M, Ince C. Calibration of Pd-porphyrin phosphorescence for oxygen concentration measurements in vivo. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:2297–2303. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.5.2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoforides C, Laasberg LH, Hedley-Whyte J. Effect of temperature on solubility of O2 in human plasma. J Appl Physiol. 1969;26:56–60. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1969.26.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]