Abstract

Molecular analysis has allowed for refinement of salivary gland tumor classification and, in some cases, the recognition of entirely new tumor types. Microsecretory adenocarcinoma (MSA) is a salivary gland tumor described in 2019 characterized by microcystic growth, bland cytomorphology, luminal secretions, fibromyxoid stroma, and S100/p63 positivity with negative p40. Most important, MSA is defined by MEF2C-SS18 fusion. While this fusion has, to this point, been detected by next-generation sequencing, this is a technique that is currently inaccessible in most diagnostic laboratories. On the other hand, SS18 break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is widely available and frequently used as an adjunct for diagnosing synovial sarcoma. It is not known if SS18 break-apart FISH is positive in tumors with MEF2C-SS18, or if it is entirely specific for MSA. Break apart FISH for SS18 was performed on 4 cases of MSA, as well as 8 tissue microarrays (TMAs) containing 423 various salivary gland carcinomas: 26 acinic cell carcinomas, 35 adenocarcinomas not otherwise specified, 96 adenoid cystic carcinomas, 3 basal cell adenocarcinomas, 20 epithelial–myoepithelial carcinomas, 15 hyalinizing clear cell carcinomas, 3 intraductal carcinomas, 12 myoepithelial carcinomas, 117 mucoepidermoid carcinomas, 30 polymorphous adenocarcinomas, 45 salivary duct carcinomas, 19 secretory carcinomas, and 2 undifferentiated carcinomas. SS18 break-apart FISH was also performed on whole slides of 2 tumors from the TMAs. All MSA cases demonstrated classic split patterns on SS18 break-apart FISH. On the TMAs, 374 cases were evaluable by FISH, and 372 cases were clearly negative for SS18 rearrangement. Two cases, both mucoepidermoid carcinomas, had rare split signals below the positivity threshold of 12% on their TMA cores, so FISH was performed on whole sections. On the whole sections both tumors were unequivocally negative for SS18 rearrangement. Taken together, SS18 break-apart FISH was 100% sensitive and 100% specific for a diagnosis of MSA. SS18 break-apart FISH, a diagnostic tool widely available in pathology laboratories, appears to be a highly accurate method for diagnosing MSA of salivary glands. Accordingly, this new tumor type may be molecularly confirmed without needing to resort to highly specialized techniques like next-generation sequencing.

Keywords: Salivary gland neoplasms, Microsecretory adenocarcinoma, MEF2C-SS18, Fluorescence in situ hybridization

Background

Molecular tools have recently begun to revolutionize salivary gland tumor classification [1]. The discovery of tumor-specific gene fusions has facilitated the recognition of novel variants of well-established tumors. For example, tumors harboring MYB fusions previously misdiagnosed as epithelial–myoepithelial carcinoma are now better recognized as adenoid cystic carcinomas [2]. In addition, tumors with MAML2 fusions that were previously called Warthin tumors are now known to be “Warthin-like” mucoepidermoid carcinomas [3, 4]. Moreover, in some instances, identifying a characteristic fusion has led to the discoveries of entirely novel tumor types. An example of this phenomenon is secretory carcinoma, a tumor previously called acinic cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, not otherwise specified before its characteristic ETV6-NTRK3 fusion was elucidated [5]. More recently, a new salivary gland tumor type known as MSA was described. In addition to its unique histologic and immunophenotypic features, the presence of a novel fusion MEF2C-SS18 allowed for its characterization [6].

Novel fusions are typically discovered using next generation sequencing (NGS), and all previously reported MSA cases were tested by NGS. This technique, however, is currently not routinely available in most diagnostic laboratories. On the other hand, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is a widely available technique that requires less specialized equipment and expertise, and often less tumor tissue to perform. Indeed, SS18 break-apart FISH is already widely available and frequently used as an adjunct for diagnosing synovial sarcoma.

While MSA is defined by a MEF2C-SS18 fusion, because SS18 break-apart FISH probes were not designed for this tumor and its breakpoints, it is not known whether SS18 break-apart FISH will be positive. Moreover, because SS18 break-apart FISH has not been previously employed on salivary gland tumors, it is unclear if any other tumor type would be positive. We sought to determine (1) if MSA is positive using commercially available SS18 break-apart FISH probes, and if it is, (2) if SS18 break-apart FISH is specific for MSA.

Methods

The study was performed with institutional review board approval (STU 112017-073). To assess sensitivity, four of the MEF2C-SS18 MSA cases from its original publication were submitted for SS18 break-apart FISH analysis [6]. The fifth MSA did not have remaining material for FISH testing.

To assess specificity, eight tissue microarrays (TMAs) containing numerous salivary carcinoma types were also subjected to SS18 break-apart FISH. The TMAs contained 423 primary salivary gland carcinomas: 26 acinic cell carcinomas, 35 adenocarcinomas not otherwise specified, 96 adenoid cystic carcinomas, 3 basal cell adenocarcinomas, 20 epithelial–myoepithelial carcinomas, 15 hyalinizing clear cell carcinomas, 3 intraductal carcinomas, 12 myoepithelial carcinomas, 117 mucoepidermoid carcinomas, 30 polymorphous adenocarcinomas, 45 salivary duct carcinomas, 19 secretory carcinomas, and 2 undifferentiated carcinomas. Two 1-mm punches were taken from each tumor. Whole sections from 2 of the cases contained on these TMAs were also submitted for FISH.

FISH was performed on sections from the TMAs of cases included in the study using a standard dual color break-apart probe (centomeric 3′-side green, telomeric 5′-side orange) for SS18 following manufacturer’s protocol (Abbott Molecular, Des Plains, IL). Briefly, the sections were deparaffinized, pre-treated for 25 minutes at 80 °C, protease treated for 38 min at 37 °C, probe and target co-denatured at 80 °C for 15 min, hybridized overnight at 37 °C, and washed at 74 °C for 2 min. Slides were stained with DAPI and evaluated using epifluoresence microscope and ASI software (Applied Spectral Imaging, Chicago, IL); 100 nuclei were evaluated from each tumor. Tumors with split signals in > 12% of cells were regarded as positive.

Results

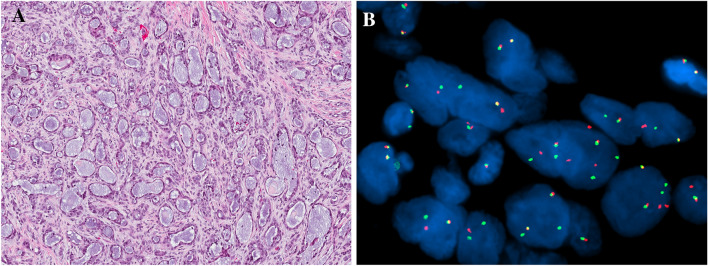

The results are summarized in Table 1. All four cases of MSA were positive for SS18 break-apart FISH with classic break apart patterns (Fig. 1) in 52 to 92% of cells (mean, 76%).

Table 1.

SS18 break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization results

| Tumor type | Positive cases/cases tested (%) |

|---|---|

| Microsecretory adenocarcinoma | 4/4 (100) |

| Acinic cell carcinoma | 0/24 (0) |

| Adenocarcinoma, not otherwise specified | 0/31 (0) |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | 0/80 (0) |

| Basal cell adenocarcinoma | 0/3 (0) |

| Epithelial–myoepithelial carcinoma | 0/19 (0) |

| Hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma | 0/11 (0) |

| Intraductal carcinoma | 0/2 (0) |

| Myoepithelial carcinoma | 0/12 (0) |

| Mucoepidermoid carcinoma | 0/105 (0) |

| Polymorphous adenocarcinoma | 0/28 (0) |

| Salivary duct carcinoma | 0/43 (0) |

| Secretory carcinoma | 0/15 (0) |

| Undifferentiated carcinoma | 0/1 (0) |

| Total | 4/378 (1) |

Fig. 1.

Microsecretory adenocarcinoma consists of uniformly sized microcysts lined by flattened cells with bluish secretions, set in a cellular fibromyxoid stroma (a). All tested microsecretory adenocarcinomas were positive with break apart SS18 break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization (red and green signals split apart) (b)

On the TMAs, 374 cases were evaluable by FISH. The remaining 49 cases either had insufficient tumor on the section, or failed hybridization. Of the evaluable cases, 372 were clearly negative for SS18 rearrangement, with no observable FISH abnormalities. Two cases, both low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinomas with classic histologic features, had an equivocal pattern on their TMA cores, with split signals seen in < 12% of cells. Although lower than the 12% threshold to regard as positive, to further investigate these cases, SS18 break-apart FISH was performed on whole sections. On the whole sections both tumors were unequivocally negative, with no cells with SS18 rearrangement seen.

Taken together, SS18 break-apart FISH was 100% sensitive and 100% specific for a diagnosis of MSA.

Discussion

In recent years, an increasing understanding of the molecular underpinnings of salivary glands tumors has considerably altered classification schemes. Recently, a tumor known as MSA was described. MSA has unique histologic (uniform microcysts lined by flattened cells and filled with bluish secretions, set in a fibromyxoid stroma) and immunophenotypic (one cell type positive for S100 and p63, and negative for p40, actin, and mammaglobin) features, and in the past it would likely have been regarded as a low-grade adenocarcinoma, not otherwise specified. Importantly, MSA also harbors a novel fusion: MEF2C-SS18. The combination of unique histologic, immunophenotypic, and genetic findings allowed for an initial description with only 5 cases [6]. One additional case has since been published [7]. The published cases have a predilection for the oral cavity, and while its histologic features are low-grade, its behavior is yet to be fully characterized.

The published cases of MSA have been confirmed by demonstrating the MEF2C-SS18 fusion by next-generation sequencing (NGS). This method is very sensitive and specific, but currently largely restricted to tertiary centers that have the infrastructure, including technical and bioinformatic support, necessary for this nascent technique. Moreover, NGS for fusion analysis requires a significant amount of well-preserved RNA which is sometimes unavailable in small biopsies, older archival, or decalcified specimens. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is more readily available and can often be performed on smaller amounts of tissue. While FISH assays for MEF2C are not easily obtainable, SS18 break-apart FISH, on the other hand, is widely available because it is commonly utilized to help diagnose synovial sarcoma, a tumor that harbors SS18 fusions in almost all cases. It is therefore tempting to assume that SS18 break-apart FISH would also be effective for identifying MSA. However, this has not previously been demonstrated, and FISH results are not always predictable. It is of limited value with cryptic events such as genes in close proximity (e.g., STAT6 in solitary fibrous tumor and RET in salivary intraductal carcinoma) [8, 9]. FISH results can also be difficult to interpret for certain tumors with inconsistent genetic events. MYB FISH patterns for adenoid cystic carcinoma, for example, are often atypical or falsely negative [10]. Finally, probe design may also result in false negatives. For MSA, the MEF2C-SS18 fusion consistently involves exon 4 of the SS18 gene, while commercial SS18 break-apart FISH probes are designed for synovial sarcoma which involves exon 10 of SS18, and are on either side of exon 11.

We found that, using commercially available probes, SS18 break apart FISH was positive in all tested cases of MSA. In addition, no other SS18-rearranged cases were found among a large group of primary salivary gland carcinomas. This underscores that MSA is seemingly quite rare. Only 6 cases have been reported, and even among 374 evaluable salivary gland carcinomas (including 31 adenocarcinomas, not otherwise specified), no additional MSA cases were uncovered on TMAs created before its description. Also, no SS18 rearrangements were unexpectedly found in other salivary gland tumor types. While the genetics of most salivary gland carcinoma types are relatively elucidated, the SS18 gene had not specifically been evaluated in salivary gland tumors. Although there were low levels of cells with positive SS18 break-apart FISH patterns on TMA cores of two mucoepidermoid carcinomas, they were below the threshold of positivity and far below the proportion of positive cells seen in confirmed MSAs. Moreover, FISH performed on whole slides from these two cases were completely negative, supporting the notion that these positive signals were not biologically relevant.

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that widely available, commercial SS18 break-apart FISH assays can be effectively used to support the diagnosis of MSA, obviating the need for NGS techniques. This finding greatly simplifies and democratizes the diagnosis of MSA. With any luck, the use of SS18 break-apart FISH will result in increasing numbers of MSAs being uncovered, which will allow for more data and a more complete understanding of this newly described tumor.

Funding

This study was funded in part by the Jane B. and Edwin P. Jenevein, MD Endowment for Pathology at UT Southwestern Medical Center.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the UT Southwestern institutional review board (STU 112017-073).

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Skalova A, Stenman G, Simpson RHW, Hellquist H, Slouka D, Svoboda T, et al. The role of molecular testing in the differential diagnosis of salivary gland carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42(2):e11–27. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishop JA, Westra WH. MYB translocation status in salivary gland epithelial–myoepithelial carcinoma: evaluation of classic, variant, and hybrid forms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42(3):319–25. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bishop JA, Cowan ML, Shum CH, Westra WH. MAML2 rearrangements in variant forms of mucoepidermoid carcinoma: ancillary diagnostic testing for the ciliated and warthin-like variants. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42(1):130–6. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishibashi K, Ito Y, Masaki A, Fujii K, Beppu S, Sakakibara T, et al. Warthin-like mucoepidermoid carcinoma: a combined study of fluorescence in situ hybridization and whole-slide imaging. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39(11):1479–87. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skalova A, Vanecek T, Sima R, Laco J, Weinreb I, Perez-Ordonez B, et al. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands, containing the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene: a hitherto undescribed salivary gland tumor entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(5):599–608. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d9efcc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bishop JA, Weinreb I, Swanson D, Westra WH, Qureshi HS, Sciubba J, et al. Microsecretory adenocarcinoma: a novel salivary gland tumor characterized by a recurrent MEF2C-SS18 fusion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43(8):1023–32. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawakami F, Nagao T, Honda Y, Sakata J, Yoshida R, Nakayama H, et al. Microsecretory adenocarcinoma of the hard palate: a case report of a recently described entity. Pathol Int. 2020;70(10):781–5. doi: 10.1111/pin.12987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng L, Zhang S, Wang L, MacLennan GT, Davidson DD. Fluorescence in situ hybridization in surgical pathology: principles and applications. J Pathol Clin Res. 2017;3(2):73–99. doi: 10.1002/cjp2.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinreb I, Bishop JA, Chiosea SI, Seethala RR, Perez-Ordonez B, Zhang L, et al. Recurrent RET gene rearrangements in intraductal carcinomas of salivary gland. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42(4):442–52. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Togashi Y, Dobashi A, Sakata S, Sato Y, Baba S, Seto A, et al. MYB and MYBL1 in adenoid cystic carcinoma: diversity in the mode of genomic rearrangement and transcripts. Mod Pathol. 2018;31:934. doi: 10.1038/s41379-018-0008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]