Abstract

Salivary gland secretory carcinoma (SSC) is a neoplasm with characteristic histologic features, similar to those of secretory carcinoma of the breast. Only a few pediatric SSC cases have been reported, all with ETV6-NTRK3 fusion. We present four new pediatric SSC examples, one with a novel ETV6-RET fusion. Four cases of SSC were diagnosed between 2010 and 2020: 2 boys, 7 and 9 year-old with parotid tumors (1.5 and 1.3 cm, respectively); and two 14 year-old girls: one with a submandibular tumor (2.1 cm), and one with a parotid lesion (1.2 cm). Histologically, all tumors were similar: well-circumscribed lesions composed by mid-size, monotonous cells with eosinophilic and sometimes vacuolated cytoplasm. The nuclei are oval to round with open chromatin and a single nucleolus. There are duct-like structures and microcysts with colloid-like material. Immunohistochemically, tumor cells are positive for S100, CK7, mammaglobin and GATA3. A classic ETV6-NTRK3 translocation was confirmed in the three parotid tumors; an ETV6-RET fusion was demonstrated in the submandibular lesion. All patients underwent complete surgical resection and are alive without tumor recurrence after a follow-up time ranging from one to 4 years. Pediatric SSC is extremely rare but their characteristic morphology and immunohphenotype facilitate their diagnosis. We describe the first pediatric case with the recently reported ETV6-RET fusion. Similar to adult cases, this tumor is morphologically undistinguishable from those carrying the classic ETV6–NTRK3 translocation. Thus, in pediatric cases with morphology suggestive of SSC and negative ETV6-NTRK3 by RT-PCR, other possible fusions should be investigated.

Keywords: Salivary gland secretory carcinoma, Pediatric salivary gland tumors, ETV6 fusion

Introduction

Salivary gland secretory carcinoma (SSC) was initially described in 2010 by Skálová et al. [1] as “mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (MASC) of the salivary glands”. In the updated 2017 WHO classification, MASC is acknowledged and referred to as ‘secretory carcinoma’, to standardize nomenclature amongst different organ sites [2]. The tumor is morphologically and immunophenotpically similar to the secretory carcinoma of the breast, and both tumors share a genetic profile with an ETV6-NTRK3 fusion [1]. ETV6-NTRK3 fusion was originally described in infantile fibrosarcoma and cellular congenital mesoblastic nephroma, which may represent a phenotypic and genotypic spectrum [3, 4].

Since the original description of SSC, multiple series of cases have been published defining their clinicopathological characteristics. More recently, the genetic spectrum of this tumor has been expanding to include new ETV6 partner genes in lesions with the same histology and immunophenotype. These new gene partners include RET [5, 6] and MAML3 [7]. ETV6-MET fusion has also been reported in a high-grade SSC [8].

To the best of our knowledge, only sixteen cases of pediatric SSC (below 18 years of age) have been reported [9–22], none of which had an ETV6-RET fusion. Overall, SSC are relatively rare in the pediatric population, and recognition of this tumor is important for proper patient management, including the potential use of targeted therapy in some clinical circumstances. Whether pediatric cases of SSC have distinctive clinicopathologic and molecular features, is not well-defined. Our aim is to present a multi-institutional collected series of four new cases of SSC in the pediatric population, one with the recently described ETV6-RET fusion, and to discuss the implications of this diagnosis in the pediatric population.

Methodology

Case Selection

The cases were retrieved from the archives of the Departments of Pathology of two referral institutions: UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh (USA) and Ospedale Bambino Gèsu, Roma, Italy, between the years 2010–2020. All cases with the diagnoses of “secretory salivary gland carcinoma” or “mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of the salivary gland” were selected for our study. Consultation cases with no available slides were excluded. Tumor morphology and immunophenotype were reviewed and the diagnosis was confirmed based on the published criteria, including a lobulated growth appearance with fibrous septa, microcystic or solid, tubular, follicular, and papillary structures with secretions in their lumina. Tumor cells feature eosinophilic cytoplasm which is most frequently vacuolated, and small, monotonous nuclei. S100 protein and mammaglobin immunohistochemistry are typically positive [2]. This study was approved by the corresponding Institutional Review Boards by written exemption, as it used only pre-existing de-identified materials and data.

Patient Clinical Information

The clinical information retrieved from clinical files, included: age at the time of diagnosis, gender, tumor location, symptoms, lymph node involvement, metastasis, treatment, recurrences, and clinical follow-up.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Specimens were fixed in 10% formalin and paraffin embedded. Sections were cut at 4-μm for Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining and immunohistochemistry studies (IHC). All primary antibodies used are summarized in Table 1. Immunochemistry was performed on the Ventana® Benchmark XT IHC following the manufacturer's instructions, with adequate controls.

Table 1.

Antibody’s clone, manufacturer and dilution used in IHC

| Antibody | Manufacturer | Clone | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|

| GATA3 | BioCellMedical | L50-823 | 1:200 |

| Mammaglobin | DAKO | 304-1 A5 | 1:100 |

| CK7 | DAKO | OU-TL 12/30 | 1:250 |

| P63 | Ventana | 4A4 | 1:800 |

| Ki67 | DAKO | MIB1 | 1:25 |

| S100 | DAKO | Polyclonal | 1:3000 |

Genetic Analysis

Molecular analyses were performed at diagnosis on formalin fixed-paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissue. RNA extraction from FFPE tissue was carried out from three-four 10-μm thick sections. Samples were deparaffinized in two changes from d-limonene, and washed three times in ethanol (100%, 90% and 70%): rehydrated tissue was then incubated in lysis buffer mixture containing proteinase-K. After 3 to 18 h of digestion at 55 °C in lysis buffer, the RNA was extracted and then resuspended in 30 μL of elution buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH7.5) (Absolutely RNA FFPE, Stratagene, Santa Clara, California). One μg of RNA was retrotranscribed to cDNA with EuroScript M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (RNase H-) (Euroclone, Milano, Italy). PCR amplification was performed by using the BIOTAQ DNA Polymerase (Bioline, London, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR reaction mixture contained 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 M of each primer, [6] 1X PCR Buffer, 0.4 mM of each dNTPs, 0.5 U of Taq polymerase, and 1 mL of the RT product in a final 20 mL reaction volume. Quality of RNA and efficiency of reverse transcription were assessed by analyzing the expression of beta2-microglobulin or GAPDH gene. PCR reaction products were electrophoresed through 2% agarose gels, and their sizes were determined by comparative analysis with DNA Marker VI (Roche, Milan, Italy).

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization Method (FISH)

ETV6 FISH analysis using LSI ETV6 Dual-color Break-apart Probe was manually performed and quantitatively assessed by analysis of a minimum of 60 cells using the ETV6 SpectrumOrange (telomeric) and the ETV6 SpectrumGreen (centromeric) probes. The image was captured using the FISH Imaging System (Leica Biosystems; CytoVision FISH Capture and Analysis Workstation; Buffalo Grove, IL). ETV6 translocation detection was performed as follows: Normal cells without the ETV6 translocation show green and orange signals in juxtaposition. Cells with the ETV6 translocation show one pair of signals (green and orange) in juxtaposition and one green and one orange signal separated. When the ETV6 range was > 10% of cells showing the translocation pattern, the result was considered abnormal.

Results

Four cases of SSC were diagnosed between 2010 and 2020: 2 boys, 7 and 9 year-old, with parotid tumors (1.5 and 1.3 cm, respectively); and two 14 year-old girls: one with a submandibular tumor (2.1 cm), and one with a parotid lesion (1.2 cm). The clinical characteristics of these tumors are described on Table 2. All tumors presented as non-painful, firm, nodules in the above-mentioned salivary glands. A neck CT with contrast showed a well-circumscribed, enhancing mass (Fig. 1), in three cases. In case number 4, the lesion was cystic with a small solid component. A fine needle aspiration of the lesion was performed before surgical resection in case 1. This showed single and cohesive epithelioid cells forming papillary structures. After a diagnosis of “epithelioid neoplasm, favor salivary gland neoplasm”, FISH analysis was negative for MAML2 translocation. All four tumors were completely excised, and the patients have been followed with imaging studies. No tumor recurrence was noted.

Table 2.

Clinical and imaging findings in four pediatric cases of salivary gland secretory carcinoma

| Case | Age (y) | Gender | Location | Size (cm) | Imaging | Treatment | Follow-up/Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7 | M | Parotid | 1.5 | Well circumscribed solid | Surgery; complete excised | 4y 4 m/ no recurrence |

| 2 | 9 | M | Parotid | 1.3 | Well circumscribed solid | Surgery; complete excised | 2y 6 m/ no recurrence |

| 3 | 14 | F | Submandibular | 2.1 | Well circumscribed solid | Surgery; Complete excised | 1y 6 m/ no recurrence |

| 4 | 14 | F | Parotid | 1.2 | Well circumscribed Partially cystic | Surgery; Complete excised | 1y/ no recurrence |

Fig. 1.

a Neck CT with contrast showing 1.5 cm mass within the parotid gland (case 1). b FNA smear showing a cellular specimen composed by cohesive epithelioid cells forming papillary structures (case 1). c Macroscopic section showing a partially encapsulated tumor with focal hemorrhage (case 1). d Low-power photomicrograph showing a predominantly cystic lesion with a small solid area (case 4)

Pathology

On macroscopic examination, all tumors were well-circumscribed with a thin capsule. As shown in Fig. 1, case 1 shows a tan-pink, soft and friable tumor, with focal hemorrhage and rupture of the capsule, possibly related to the previous fine needle aspiration (Fig. 2a, b). Three tumors were predominantly solid with focal microcystic areas, and one was mostly cystic with a small solid area (Fig. 1d).

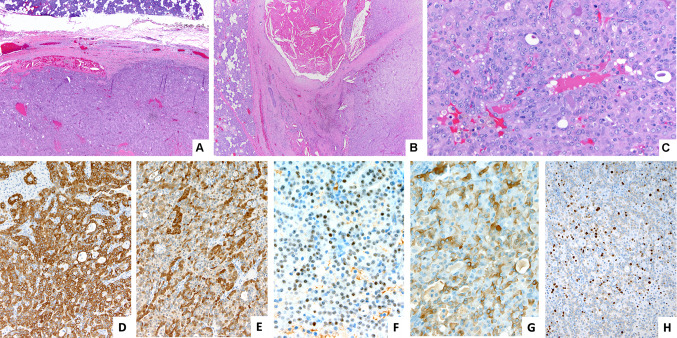

Fig. 2.

Representative images of the tumor with ETV6-NTRK3 fusion (case 1). a HE 40X. b HE 100X. c HE 400X. Immunohistochemistry. d cytokeratin 7, e S-100, f GATA3 g Mammaglobin and h Ki67 (D to H 200X)

Histologically, all tumors were similar and show a well-circumscribed lesion surrounded by fibrous tissue with focal inflammation. The tumors are composed of mid-size, monotonous cells with eosinophilic and sometimes vacuolated cytoplasm. The nuclei are oval to round, with open chromatin and a single nucleolus. There are duct-like luminal structures and microcysts, filled by eosinophilic colloid-like material with a "bubbly" appearance (Figs. 2 and 3). No vascular or perineural invasion were identified, and the margins of resection were free of tumor. IHC showed in all cases tumor cells positive for cytokeratin 7, S100, GATA3 and mammaglobin (Figs. 2 and 3), and negative for cytokeratin 5/6 and p63. Ki-67 shows a proliferative index of approximately 20–30%.

Fig. 3.

Representative images of the tumor with ETV6-RET fusion (case 3). a HE 40X. b HE 100X. c HE 200X. Immunohistochemistry. d cytokeratin 7, e Mammaglobin and f GATA3 (D to F 200X)

The diagnosis was confirmed by molecular studies in all cases (Table 3). Cases 1 and 4 were initially diagnosed by positive FISH for ETV6 rearrangement, and ETV6-NTRK3 fusion was confirmed by RT-PCR. Case 2 was positive for ETV6-NTRK3 fusion by RT-PCR. Case 3 was initially evaluated by RT-PCR for ETV6-NTRK3 fusion, which was negative. Because of a strong suspicion for SSC, FISH analysis was performed and revealed an ETV6 translocation. RT-PCR was performed for other genes fusion partners, and the ETV6-RET fusion was detected.

Table 3.

Pathologic, immunohistochemical and molecular findings in four pediatric cases of salivary gland secretory carcinoma

| Case | Histology/cytomorphology | IHC | FISH ETV6 break |

RT-PCR ETV6-NTRK3 |

RT-PCR ETV6-RET |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Partially encapsulated; Solid, microcystic; vacuolated eosinophilic cytoplasm, small, monotonous nuclei |

+ CK7 + S100 + GATA3 + mammaglobin |

+ | + | ND |

| 2 |

Encapsulated; Solid, microcystic; vacuolated eosinophilic cytoplasm, small, monotonous nuclei |

+ CK7 + S100 + GATA3 + mammaglobin |

+ | + | ND |

| 3 |

Encapsulated; Solid, microcystic; vacuolated eosinophilic cytoplasm, small, monotonous nuclei |

+ CK7 + S100 + GATA3 + mammaglobin |

+ | − | + |

| 4 |

Encapsulated; Solid, macrocystic; vacuolated eosinophilic cytoplasm, small, monotonous nuclei |

+ CK7 + S100 + GATA3 + mammaglobin |

+ | + | ND |

Discussion

Secretory carcinoma of the salivary gland occurs predominantly in adults with a predilection for the parotid gland. It is rare in the pediatric population and, to the best of our knowledge, only sixteen cases (Table 4), below 18 years of age, had been published to date [9–22]. We report here four additional pediatric cases of SSC, with molecular analysis and patient follow-up.

Table 4.

List of SSC cases published previously under the age of 18 years

| Author, year | Age (years) | Gender | location | Molecular test/results | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Griffith 2011 [9] | 15 | M | Upper lip | FISH ETV6: + | NA |

| Rastatter 2012 [17] | 14 | F | Parotid |

RT-PCR: + ETV6-NTRK3 |

No evidence of disease—12 months |

| Woo 2014 [22] | 14 | F | Parotid | FISH ETV6: + | NA |

| Hwang 2014 [11] | 13 | M | Parotid |

FISH ETV6: + RT-PCR: + ETV6-NTRK3 |

No evidence of disease—8 months |

| Majewska 2015 [14] | 17 | M | Parotid | FISH ETV6: + | No evidence of disease—10 years |

| Urano 2015 [21] | 14 | F | Parotid |

FISH ETV6: + RT-PCR: + ETV6-NTRK3 |

No evidence of disease > 30 years |

| Quattlebaum 2015 [16] | 15 | F | Parotid | FISH ETV6: + | NA |

| Jung 2015 [13] |

1. 17 2. 17 |

1. F 2. M |

1. Parotid 2. Parotid |

1. FISH ETV6: + 2. FISH ETV6: + |

1. Local recurrence six times during 15 years after first resection surgery 2. NA |

| Ito 2015 [12] | 10 | M | Submandibular |

FISH ETV6: + FISH NTRK3: + RT-PCR: negative ETV6-NTRK3 |

NA |

| Shah 2015 [18] | 16 | M | Parotid | FISH ETV6: negative | NA |

| Skálová 2016 [20] |

1. 15 2. 17 |

M |

1. Submandibular 2. Parotid |

1 & 2 FISH ETV6: + FISH NTRK3: + RT-PCR: + ETV6-NTRK3 |

1. No evidence of disease—4 years 2. No evidence of disease—12 years |

| Ngouajio 2017 [15] | 14 | M | Parotid | FISH ETV6: + | No evidence of disease—4 months |

| Shigeta, 2018 [19] | 7 | M | Parotid | RT-PCR: + ETV6-NTRK3 | No evidence of disease—20 months |

| Hernandez-Prera 2019 [10] | 17 | F | Parotid | FISH ETV6: negative | NA |

Most of our cases carried ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene, as it was initially described in 2010 by Skálová et al. [1]. This translocation results in the fusion of a transcriptional regulator, the ETV6 gene, with a membrane-receptor kinase, the NTRK3 gene. The fusion leads to a constitutively active chimeric tyrosine kinase [23]. In the pediatric population, the same translocation was previously and originally found in congenital (infantile) fibrosarcoma [3], and the related neoplasm known as congenital mesoblastic nephroma of the cellular variant [4]. Some cases of thyroid papillary carcinoma and acute myeloid leukemia have also shown this translocation [24]. More recently, other gene fusions have been described in adults with salivary secretory carcinomas. These include different ETV6 partners, such as RET [5, 7] and MET [8].

A novel finding in our series is the case of a teenage girl with a submandibular tumor negative for ETV6-NTRK3 fusion by RT-PCR. This tumor was morphologically and immunohphenotypically consistent with SSC, and the FISH analysis using the ETV6 break-apart probe was positive. However, RT-PCR and NGS studies confirmed the recently described ETV6-RET fusion. The finding of an ETV6 partner different from NTRK3 is an important novel observation in pediatric cases, which cannot only help to confirm the diagnosis, but it also translates into possible gene targeted therapy. SSCs with the classic ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion are known to respond to new specific tyrosine kinase inhibitors, or to the second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors [25], but the RET—fusion-positive tumors would be unresponsive to these agents. However, there are specific RET inhibitors under development, which could be effective on these RET positive fusion SSCs [26].

Similar to the case described here, the majority of the pediatric patients with SSC have a clinical history of a painless, slow-growing mass, but cases with pain and facial paralysis have been also described [15]. Also, similar to our cases, the most frequent location of the SSC is the parotid (70% of cases), followed by the submandibular gland [15]. Macroscopically, three tumors were predominantly solid with a variably microcystic component; and one (case #4) is a predominantly cystic lesion, similar to some cases with macrocystic appearance recently described in adults, and one case of a 17-year old patient [10]. This highlights the importance of including SSC in the differential diagnosis of a cystic salivary gland lesion in the pediatric population.

In contrast with most tumors in adults, generally described as non-encapsulated or even infiltrative lesions, all four cases described here are well-circumscribed and encapsulated neoplasms [27]. The cytomorphology and immunophenotype of our tumors are similar to those previously described in the pediatric and adult populations, with no difference noted among the two ETV6 partners. All described pediatric SSC are low-grade neoplasms and show low mitotic rate, no necrosis, and are negative for perineural or lymphovascular invasion.

The most important differential diagnosis for SSC is acinic cell carcinoma (AcCC), but in general, tumor cells of AcCC have basophilic cytoplasm with zymogen granules and more cytological diversity than SSC. Zymogen-poor AcCC can be difficult to differentiate from SSC on H&E, but on IHC, AcCC will be negative for S100 protein and mammaglobin. Most SSC are negative for DOG1 satining, while the vast majority of low and high-grade AcCCs, are positive for this marker [28, 29]. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC), the most frequent salivary gland tumor in children and adolescents, is also a differential diagnosis of SSC in pediatric cases. In a surgical specimen, the distinction between SSC and MEC based on H&E is not that difficult, because they are morphologically distinct tumors, but on cytological samples, the differentiation can be more challenging. In cytological specimens, IHC and molecular studies can help to differentiate SSC and MEC. The cytology specimen of the case described here, excluded MEC based on a negative FISH for MAML2 translocation.

Although SSC is currently regarded as a low-grade malignancy with favorable prognosis, it has the potential for an aggressive course. There are reports of adult cases with local recurrence, high-grade transformation, as well as regional lymph node and distant metastases [27]. However, data on pediatric SSC management, outcomes and prognosis need studies with long-term follow up. In a recent systematic review after 7 years of the tumor description, Khalele concluded that close follow-up is recommended, “…especially when necrosis, increased mitotic activity, and other classic caveats are conspicuous” [30]. Due to the negative surgical margins, and the absence of perineural and vascular invasion, all patients described here received no postoperative additional therapy, and with a relatively long follow-up (over one year in all cases), there is no evidence of recurrences.

Acknowledgment

Supported in part by the Marjory K. Harmer Endowment for Research in Pediatric Pathology (MRM).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Materials were collected after written exception issued by the Institutional Review Boards of the corresponding institutions, as the study used only pre-existing de-identified materials and data for which no informed consent was deemed necessary.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Skalova A, Vanecek T, Sima R, Laco J, Weinreb I, Perez-Ordonez B, et al. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands, containing the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene: a hitherto undescribed salivary gland tumor entity. Am J SurgPathol. 2010;34(5):599–608. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d9efcc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skálová A, Bishop JA, Bell D, Inagaki H, Seethala R, Vielh P. Secretory carcinoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classsification of head and neck tumours. 4. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2017. pp. 177–178. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knezevich SR, McFadden DE, Tao W, Lim JF, Sorensen PH. A novel ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion in congenital fibrosarcoma. Nat Genet. 1998;18(2):184–187. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubin BP, Chen CJ, Morgan TW, Xiao S, Grier HE, Kozakewich HP, et al. Congenital mesoblasticnephroma t(12;15) is associated with ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion: cytogenetic and molecular relationship to congenital (infantile) fibrosarcoma. Am J Pathol. 1998;153(5):1451–1458. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65732-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Black M, Liu CZ, Onozato M, Iafrate AJ, Darvishian F, Jour G, et al. Concurrent identification of novel EGFR-SEPT14 fusion and ETV6-RET fusion in secretory carcinoma of the salivary gland. Head Neck Pathol. 2020;14(3):817–821. doi: 10.1007/s12105-019-01074-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skalova A, Vanecek T, Martinek P, Weinreb I, Stevens TM, Simpson RHW, et al. Molecular profiling of mammary analog secretory carcinoma revealed a subset of tumorsharboring a novel ETV6-RET translocation: report of 10 cases. Am J SurgPathol. 2018;42(2):234–246. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guilmette J, Dias-Santagata D, Nose V, Lennerz JK, Sadow PM. Novel gene fusions in secretory carcinoma of the salivary glands: enlarging the ETV6 family. Hum Pathol. 2019;83:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2018.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rooper LM, Karantanos T, Ning Y, Bishop JA, Gordon SW, Kang H. Salivary secretory carcinoma with a novel ETV6-MET fusion: expanding the molecular spectrum of a recently described entity. Am J SurgPathol. 2018;42(8):1121–1126. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffith C, Seethala R, Chiosea SI. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma: a new twist to the diagnostic dilemma of zymogen granule poor acinic cell carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2011;459(1):117–118. doi: 10.1007/s00428-011-1098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernandez-Prera JC, Holmes BJ, Valentino A, Harshan M, Bacchi CE, Petersson F, et al. Macrocystic (mammary analogue) secretory carcinoma: an unusual variant and a pitfall in the differential diagnosis of cystic lesions in the head and neck. Am J SurgPathol. 2019;43(11):1483–1492. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hwang MJ, Wu PR, Chen CM, Chen CY, Chen CJ. A rare malignancy of the parotid gland in a 13-year-old Taiwanese boy: case report of a mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of the salivary gland with molecular study. Med MolMorphol. 2014;47(1):57–61. doi: 10.1007/s00795-013-0051-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito Y, Ishibashi K, Masaki A, Fujii K, Fujiyoshi Y, Hattori H, et al. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands: a clinicopathologic and molecular study including 2 cases harboring ETV6-X fusion. Am J SurgPathol. 2015;39(5):602–610. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jung MJ, Kim SY, Nam SY, Roh JL, Choi SH, Lee JH, et al. Aspiration cytology of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of the salivary gland. DiagnCytopathol. 2015;43(4):287–293. doi: 10.1002/dc.23208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Majewska H, Skalova A, Stodulski D, Klimkova A, Steiner P, Stankiewicz C, et al. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands: a new entity associated with ETV6 gene rearrangement. Virchows Arch. 2015;466(3):245–254. doi: 10.1007/s00428-014-1701-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ngouajio AL, Drejet SM, Phillips DR, Summerlin DJ, Dahl JP. A systematic review including an additional pediatric case report: Pediatric cases of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma. Int J PediatrOtorhinolaryngol. 2017;100:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quattlebaum SC, Roby B, Dishop MK, Said MS, Chan K. A pediatric case of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma within the parotid. Am J Otolaryngol. 2015;36(6):741–743. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rastatter JC, Jatana KR, Jennings LJ, Melin-Aldana H. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of the parotid gland in a pediatric patient. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146(3):514–515. doi: 10.1177/0194599811419044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah AA, Wenig BM, LeGallo RD, Mills SE, Stelow EB. Morphology in conjunction with immunohistochemistry is sufficient for the diagnosis of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2015;9(1):85–95. doi: 10.1007/s12105-014-0557-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shigeta R, Orgun D, Mizuno H, Hayashi A. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma arising in the parotid gland of child. PlastReconstrSurg Glob Open. 2018;6(12):e2059. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skalova A, Vanecek T, Simpson RH, Laco J, Majewska H, Baneckova M, et al. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands: molecular analysis of 25 ETV6 gene rearranged tumors with lack of detection of classical ETV6-NTRK3 fusion transcript by standard RT-PCR: report of 4 cases harboring ETV6-X gene fusion. Am J SurgPathol. 2016;40(1):3–13. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urano M, Nagao T, Miyabe S, Ishibashi K, Higuchi K, Kuroda M. Characterization of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of the salivary gland: discrimination from its mimics by the presence of the ETV6-NTRK3 translocation and novel surrogate markers. Hum Pathol. 2015;46(1):94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woo J, Seethala RR, Sirintrapun SJ. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of the parotid gland as a secondary malignancy in a childhood survivor of atypical teratoidrhabdoidtumor. Head Neck Pathol. 2014;8(2):194–197. doi: 10.1007/s12105-013-0481-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lannon CL, Sorensen PH. ETV6-NTRK3: a chimeric protein tyrosine kinase with transformation activity in multiple cell lineages. Semin Cancer Biol. 2005;15(3):215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Euhus DM, Timmons CF, Tomlinson GE. ETV6-NTRK3–Trk-ing the primary event in human secretory breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2002;2(5):347–348. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drilon A. TRK inhibitors in TRK fusion-positive cancers. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(Suppl 8):23–30. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li AY, McCusker MG, Russo A, Scilla KA, Gittens A, Arensmeyer K, et al. RET fusions in solid tumors. Cancer Treat Rev. 2019;81:101911. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2019.101911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skálová A, Baneckova M, Thompson LDR, Ptakova N, Stevens TM, Brcic L, et al. Expanding the molecular spectrum of secretory carcinoma of salivary gland with a novel VIM-RET fusion. Am J SurgPathol. 2020;44(10):1295–1307. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khurram SA, Speight PM. Characterisation of DOG-1 expression in salivary gland tumours and comparison with myoepithelial markers. Head Neck Pathol. 2019;13(2):140–148. doi: 10.1007/s12105-018-0917-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson LD, Aslam MN, Stall JN, Udager AM, Chiosea S, McHugh JB. Clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic characterization of 25 cases of acinic cell carcinoma with high-grade transformation. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10(2):152–160. doi: 10.1007/s12105-015-0645-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khalele BA. Systematic review of mammary analog secretory carcinoma of salivary glands at 7 years after description. Head Neck. 2017;39(6):1243–1248. doi: 10.1002/hed.24755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]