Keywords: primary cilia, lipid raft dynamics, Akt, adipogenesis, cancer

Abstract

Primary cilia, antenna-like structures of the plasma membrane, detect various extracellular cues and transduce signals into the cell to regulate a wide range of functions. Lipid rafts, plasma membrane microdomains enriched in cholesterol, sphingolipids and specific proteins, are also signalling hubs involved in a myriad of physiological functions. Although impairment of primary cilia and lipid rafts is associated with various diseases, the relationship between primary cilia and lipid rafts is poorly understood. Here, we review a newly discovered interaction between primary cilia and lipid raft dynamics that occurs during Akt signalling in adipogenesis. We also discuss the relationship between primary cilia and lipid raft-mediated Akt signalling in cancer biology. This review provides a novel perspective on primary cilia in the regulation of lipid raft dynamics.

1. Introduction

Primary cilia are non-motile, 1–10 µm long antenna-like structures observed in a variety of vertebrate cells. Primary cilia sense extracellular signals, such as biochemical and mechanical stimuli, and transduce these signals into the cell to regulate functions such as differentiation and proliferation [1–11]. Primary cilia convey a wide range of signals, including the signalling pathways of hedgehog, receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) and G protein-coupled receptors such as lysophosphatidic acid receptors [12,13]. Thus, the structure and function of primary cilia are appropriately regulated in normal physiology and their dysregulation is associated with various human diseases [5,9,14,15].

Lipid rafts are nanoscale membrane microdomains where lipids, such as cholesterol and sphingolipids, are enriched [16–20]. Specific proteins assemble with these lipids and mediate signalling in response to intra- or extracellular stimuli [21]. Therefore, lipid rafts work as compartmentalized platforms to regulate signalling for multiple cellular functions, including proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis [22,23]. The serine/threonine kinase, Akt, is a representative signalling protein associated with lipid rafts [24–26]. For example, Akt is activated by the insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) pathways, which is facilitated by lipid rafts [22,23]. In the presence of these ligands, the insulin receptor (IR) and the IGF1 receptor (IGF1R) phosphorylate IR substrate, which activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K). Activated PI3K produces phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3) by phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2). PIP3 binds to the pleckstrin homology domain of Akt, promoting the binding of Akt to phosphatidylinositol-dependent protein 1 (PDK1) and mammalian target of rapamycin complex (mTORC)2, which phosphorylate Thr308 and Ser473 of Akt, respectively. All these components are located in lipid rafts, increasing the efficiency of Akt activation. Phosphorylated Akt regulates downstream signalling proteins in fundamental cellular functions, whereas over-activation of lipid raft-mediated Akt signalling is associated with various metabolic diseases [22,23].

Although both primary cilia and lipid rafts act as signalling hubs, their relationship has been poorly understood. In this review, we explain a novel role of primary cilia on certain types of lipid raft dynamics related to IR–Akt signalling upon adipogenic stimuli in mouse adipose progenitor cells (APs) and mouse mesenchymal progenitor C3H10T1/2 cells [27]. We also discuss potential therapeutic approaches for obesity and cancer targeting lipid raft dynamics and primary cilia.

2. Lipid rafts in the regulation of RTKs signalling

RTKs, such as IR, IGF1R, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), are transmembrane proteins that are activated by ligand binding, which usually causes dimerization and/or oligomerization of the receptors followed by trans-autophosphorylation of multiple tyrosine residues [28]. The phosphorylated RTKs activate various downstream signalling pathways, such as the PI3K–Akt cascade, the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade and the Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription cascade [28]. Some of the RTKs signallings events can be modulated by lipid rafts [29–31]. The mechanisms include positive or negative regulation of RTK trans-phosphorylation by clustering within the lipid rafts and concentration or exclusion of signalling molecules downstream of RTKs within lipid rafts [29,30,32].

Lipid rafts can be grouped based on the main components [30,31,33–35]. Caveolins and flotillins are representative scaffold proteins in lipid rafts [31,33]. Caveolin 1 (CAV1) inserts into the inner leaflet of the membrane via a hairpin loop with the N- and C-termini exposed to the cytoplasm [36]. The N-terminal domain facilitates the formation of homo-oligomers [37] and interaction with other proteins that have a binding motif to CAV1 (e.g. IR) [36,38]. In the presence of Caveolae-associated protein 1, CAV1 can make caveola, structurally a unique lipid raft that is characterized by flask-shaped invagination of the plasma membrane [39]. CAV1 accelerated IR–Akt signalling in the differentiation of preadipocytes and the energy metabolism of adipocytes [27,40]. By contrast, CAV1 inhibited the autophosphorylation of EGFR and PDGFR in epidermoid carcinoma and fibroblasts, respectively [41,42]. Flotillins are two homologous proteins, flotillin 1 and flotillin 2 [43]. Flotillin 1 positively regulated the phosphorylation of EGFR and a substate of FGFR in HeLa cells [44,45]. The correlation between the composition and the function of lipid rafts, however, remains elusive [17].

3. Primary cilia regulate lipid raft dynamics related to IR–Akt signalling in adipogenesis

Adipogenesis plays an important and complex role in metabolic health [46]. Differentiation from preadipocytes to adipocytes is an adaptive response to nutritional overload [47]. Of note, adipogenesis can be detrimental depending on the context. For example, adipogenesis in the skeletal muscle induced by over-nutrition impairs wound healing [48]. Adipogenesis in bone marrow caused by ageing is associated with an increased risk of bone fracture [49]. Primary cilia are involved in this physiological and pathological adipogenesis. Differentiation from preadipocytes to adipocytes is stimulated by adipogenic signalling through activation of IR/IGF1R located at the ciliary base [27,50]. Upon adipogenic stimulation, IR/IGF1R observed at the region surrounding the ciliary base stimulate the PI3K–Akt pathway [27,51,52]. The activated Akt increases the expression of PPARγ, the master regulator of adipogenesis, by inhibiting the translocation of FOXO1, a key transcriptional suppressor in adipogenesis, to the nucleus of preadipocytes [53,54]. Impairment of IR signalling was associated with the metabolic dysfunction in Bardet–Biedl syndrome, a rare autosomal recessive ciliopathy [55–57]. Primary cilia also regulate adipogenesis through omega-3 fatty acid-activated FFAR4/GPR120 and desert hedgehog-activated smoothened [58,59]. However, the relationship between primary cilia and lipid rafts in the regulation of Akt signalling remains largely unknown [26,60].

We have shown that trichoplein (TCHP), a centriolar protein originally identified as a keratin-binding protein, is a key activator of aurora A kinase (AURKA) at centrioles and that knockdown (KD) of TCHP causes elongation of primary cilia in human retinal pigmental epithelium cells by suppressing the inhibitory effect of AURKA in ciliogenesis [7,61–66]. We recently found that Tchp knockout (KO) mice show elongated cilia in APs, reduced body fat and smaller adipocytes than wild-type mice under a high-fat diet [27]. In APs from wild-type mice, CAV1- or ganglioside GM3-positive lipid rafts moved to the ciliary base upon adipogenic stimulation [27] (figure 1a), while GM1 and flotillin-2, other markers of lipid rafts, did not accumulate around the primary cilia [27]. In APs from Tchp KO mice, all four types of lipid rafts did not appear near the ciliary base upon adipogenic stimulation.

Figure 1.

Elongated primary cilia in mouse mesenchymal progenitor C3H10T1/2 cells affect lipid raft dynamics at the ciliary base upon adipogenic stimuli and the formation of actin filaments beneath the cilia. (a) Immunocytological analysis of C3H10T1/2 cells before (0 min) and after (10 min) adipogenic stimulation. The lipid rafts were stained using anti-Caveolin 1 (CAV1) and anti-GM3 antibodies. The primary cilia and nuclei were stained using an anti-acetylated tubulin or anti-Arl13b antibody and Hoechst33342, respectively. (b) Immunocytological analysis of CAV1, primary cilia and nuclei in C3H10T1/2 cells treated with non-targeting control siRNA (siNC), siRNA for trichoplein (siTchp) or siRNAs for trichoplein and Ift88 (siTchp + siIft88). (c) Immunocytological analysis of primary cilia, actin filaments and nuclei in C3H10T1/2 cells treated with siNC, siTchp or siTchp + siIft88. Actin filaments were stained using fluorescent phalloidin. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

We also found that lipid raft dynamics were impaired in C3H10T1/2 cells with Tchp KD, in which the primary cilia were elongated, but not in C3H10T1/2 cells with double KD of Tchp and Ift88, in which the elongation of primary cilia caused by Tchp KD was suppressed by concomitant KD of Ift88, resulting in primary cilia being of similar length to that of control C3H10T1/2 cells [27] (figure 1b). The phosphorylation of Akt in mouse APs upon adipogenesis and the differentiation into adipocytes were also suppressed by Tchp KD but not by double Tchp and Ift88 KD [27]. The correlation between the impaired accumulation of CAV1-positive lipid rafts and the decreased phosphorylation of Akt at the ciliary base where IRs are localized is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that CAV1 positively modulates IR/IGF1R-Akt signalling in adipogenesis [67,68].

The finding that primary cilia regulate Akt signalling in adipogenesis by modulating lipid raft dynamics provides a novel perspective on the crosstalk between primary cilia and lipid rafts [27]. Co-localization of actin filaments with primary cilia was significantly lower in C3H10T1/2 cells with Tchp KD than in control C3H10T1/2 cells or C3H10T1/2 cells with double Tchp and Ift88 KD (figure 1c). CAV1 clusters are tethered to cortical actin filaments through interaction with filamin, an actin-binding protein [69]. These results indicate that the elongated cilia in C3H10T1/2 cells caused by Tchp KD may affect lipid raft dynamics through impairment of the actin-based transport system. The mechanisms by which primary cilia regulate lipid raft dynamics warrant further examination.

4. Primary cilia and lipid raft-mediated Akt signalling in cancer biology

Lipid raft-mediated Akt signalling is over-activated in various types of cancer, including prostate cancer and melanoma [26,70–73]. Phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted from chromosome 10 (PTEN) inhibits Akt activity through dephosphorylation of PIP3 to PIP2 [74]. Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) also inhibits Akt activity through dephosphorylation of Thr308 and Ser473 of Akt [75]. The loss of PTEN is frequently observed in both prostate cancer and melanoma [76,77]. Impairment of PP2A is also reported in these cancers [78,79]. Lipid raft-mediated Akt signalling is over-activated by impairment of PTEN or PP2A [80–82]. Sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP1) is positively regulated by the PI3K–Akt–mTORC1 pathway [83,84]. In fact, the activity of SREBP1 is increased in both prostate cancer and melanoma [85]. Activation of SREBP1 also stimulates PI3K–Akt signalling [84,86]. Various therapeutic approaches for cancer have been developed that target PI3K, PTEN, Akt, PP2A, or the organization of these molecules in lipid rafts [23,71,73,87–93].

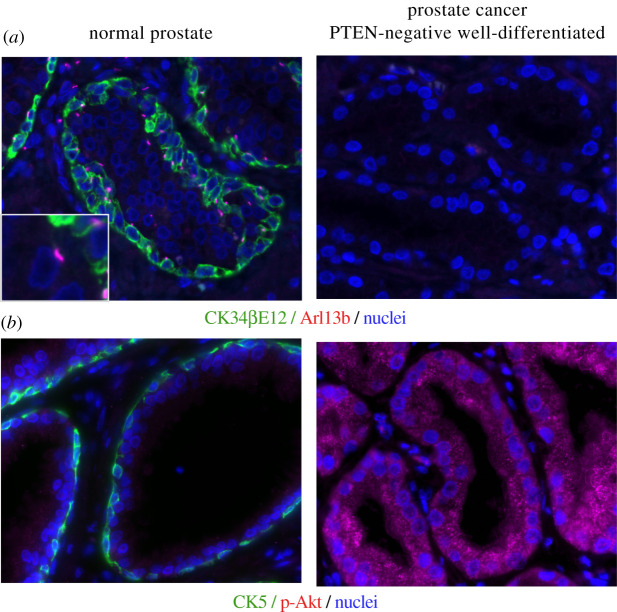

Interestingly, primary cilia are often lost in prostate cancers and melanoma [94–98] (figure 2). Knockdown of SREBP1 restored primary cilia to A375 melanoma cells [99]. Knockdown of fatty acid synthase, a transcriptional target of SREBP1, also restored primary cilia to the prostate cancer cell line, LNCaP [100]. Treatment with rapamycin, an mTORC1 inhibitor, restored the impaired ciliogenesis of prostate cancer cell lines (PC3 and DU145) and inhibited their proliferation [101], which is consistent with studies demonstrating that primary cilia work as a brake on cell proliferation [6–10,63,64,66,102].

Figure 2.

Loss of primary cilia and increase of phosphorylated Akt in PTEN-negative and well-differentiated prostate cancer. Immunohistological analysis of basal cell, primary cilia and nuclei (a), or basal cell, phosphorylated Akt and nuclei (b), in normal prostate and PTEN-negative well-differentiated prostate cancer. Basal cells were stained using an anti-CK34βE12 antibody to detect cytokeratin (CK) 1/5/10/14 (a) or an anti-CK5 antibody (b). The primary cilia and nuclei were stained using an anti-Arl13b antibody and DAPI, respectively. Phosphorylated Akt was stained using an anti-phosphorylated Akt antibody.

5. Therapeutic approaches targeting lipid raft dynamics through primary cilia

Lipid rafts have attracted attention as a novel target in cancer therapy [23,71,73,103,104]. For example, T0901317, a liver X receptor agonist, suppressed lipid raft-mediated Akt signalling affecting the localization and expression of flotillin-2 in a prostate cancer cell line, LNCaP, and a breast cancer cell line, MCF-7 [105,106]. Rh2, a major bioactive constituent of Panax ginseng, a traditional medicine, inhibited lipid raft-mediated Akt signalling, which affected the dynamics of CAV1 and GM1 in an epidermoid carcinoma cell line, A431 [107]. Edelfosin and perifosine, single-chain alkylphospholipids, suppressed the phosphorylation of Akt and the growth of patient-derived xenografts of mantle cell lymphoma [108]. Strategies for improving the efficacy and safety of these therapeutic drugs have been actively developed [109–111]. Statins can also be classified as anti-cancer agents that inhibit lipid raft-mediated Akt signalling [71,73,103,104].

The possibility that primary cilia may take part in lipid raft dynamics [27] provides a novel approach to modulate lipid raft-mediated Akt signalling through targeting primary cilia. Genome-wide screens have identified various ciliary proteins that directly regulate ciliogenesis and the associated proteins that regulate the expression and function of these ciliary proteins [64,66,112–119]. Multi-omics approaches, including lipidomics and glycomics, can also be used to identify novel components involved in the formation of primary cilia and lipid raft-mediated signalling. For example, O-linked β-N-acetylglycosaminylation (O-GlcNAcylation) is related to lipid raft-mediated Akt signalling [120,121] and ciliogenesis [122,123], and is associated with obesity, diabetes and cancer [124–126]. Modulation of O-GlcNAcylation may be a novel therapeutic approach to regulate lipid raft dynamics and primary cilia.

AURKA inhibitors, as well as Akt inhibitors, have been developed and evaluated in cancer and obesity [102,127–131]. In mouse preadipocytes, KD of Aurka, a downstream target of Tchp [63], stimulated elongation of primary cilia and inhibited IR–Akt signalling and adipogenesis [27]. This suggests that forced elongation of primary cilia caused by AURKA inhibition may rectify the dysregulation of cell proliferation and/or differentiation caused by impairment of ciliogenesis in cancer and obesity.

Identification of novel factors involved in ciliogenesis and lipid raft dynamics in specific cell types may provide critical information to understand the pathophysiology of diseases associated with the dysregulation of these signalling pathways, which could lead to the development of novel therapeutic drugs targeting lipid raft dynamics and primary cilia.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely apologize to all researchers whose important works are not cited in this review. We thank Jeremy Allen, PhD, from Edanz (https://www.edanz.com/) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Data accessibility

This article has no additional data.

Authors' contributions

M.I.: conceptualization. D.Y., K.U. and T.S.: methodology. Y.N., D.Y., K.U., T.S., M.W. and M.I.: investigation. Y.N. and M.I: writing.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (19K07318 to Y.N., 20K07356 to D.Y., 20K07371 to K.U., 18K06890 to T.S., 19K09708 to M.W. and 21H02696 to M.I.), the Takeda Science Foundation (to Y.N., D.Y. and M.I.) and the Naito Foundation (to M.I.).

References

- 1.Malicki JJ, Johnson CA. 2017. The cilium: cellular antenna and central processing unit. Trends Cell Biol. 27, 126-140. ( 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.08.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia G III, Raleigh DR, Reiter JF. 2018. How the ciliary membrane is organized inside-out to communicate outside-in. Curr. Biol. 28, R421-R434. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2018.03.010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elliott KH, Brugmann SA. 2018. Sending mixed signals: cilia-dependent signaling during development and disease. Dev. Biol. 447, 28-41. ( 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.03.007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang L, Dynlacht BD. 2018. The regulation of cilium assembly and disassembly in development and disease. Development (Cambridge, England) 145, dev151407. ( 10.1242/dev.151407) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anvarian Z, Mykytyn K, Mukhopadhyay S, Pedersen LB, Christensen ST. 2019. Cellular signalling by primary cilia in development, organ function and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 15, 199-219. ( 10.1038/s41581-019-0116-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goto H, Inoko A, Inagaki M. 2013. Cell cycle progression by the repression of primary cilia formation in proliferating cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 70, 3893-3905. ( 10.1007/s00018-013-1302-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Izawa I, Goto H, Kasahara K, Inagaki M. 2015. Current topics of functional links between primary cilia and cell cycle. Cilia 4, 12. ( 10.1186/s13630-015-0021-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goto H, Inaba H, Inagaki M. 2017. Mechanisms of ciliogenesis suppression in dividing cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 74, 881-890. ( 10.1007/s00018-016-2369-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishimura Y, Kasahara K, Shiromizu T, Watanabe M, Inagaki M. 2019. Primary cilia as signaling hubs in health and disease. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 6, 1801138. ( 10.1002/advs.201801138) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishimura Y, Kasahara K, Inagaki M. 2019. Intermediate filaments and IF-associated proteins: from cell architecture to cell proliferation. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 95, 479-493. ( 10.2183/pjab.95.034) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferreira R, Fukui H, Chow R, Vilfan A, Vermot J. 2019. The cilium as a force sensor—myth versus reality. J. Cell Sci. 132, jcs213496. ( 10.1242/jcs.213496) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walia V, et al. 2019. Akt regulates a Rab11-effector switch required for ciliogenesis. Dev. Cell 50, 229-246.e227. ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.05.022) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu H-B, et al. 2021. LPA signaling acts as a cell-extrinsic mechanism to initiate cilia disassembly and promote neurogenesis. Nat. Commun. 12, 662. ( 10.1038/s41467-021-20986-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reiter JF, Leroux MR. 2017. Genes and molecular pathways underpinning ciliopathies. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 533-547. ( 10.1038/nrm.2017.60) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu S, Trupiano MX, Simon J, Guo J, Anton ES. 2021. The essential role of primary cilia in cerebral cortical development and disorders. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 142, 99-146. ( 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2020.11.003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simons K, Ikonen E. 1997. Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature 387, 569-572. ( 10.1038/42408) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levental I, Levental KR, Heberle FA. 2020. Lipid rafts: controversies resolved, mysteries remain. Trends Cell Biol. 30, 341-353. ( 10.1016/j.tcb.2020.01.009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sezgin E, Levental I, Mayor S, Eggeling C. 2017. The mystery of membrane organization: composition, regulation and roles of lipid rafts. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 361-374. ( 10.1038/nrm.2017.16) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Deventer S, Arp AB, van Spriel AB. 2021. Dynamic plasma membrane organization: a complex symphony. Trends Cell Biol. 31, 119-129. ( 10.1016/j.tcb.2020.11.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pike LJ. 2006. Rafts defined: a report on the Keystone symposium on lipid rafts and cell function. J. Lipid Res. 47, 1597-1598. ( 10.1194/jlr.E600002-JLR200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simons K, Sampaio JL. 2011. Membrane organization and lipid rafts. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3, a004697. ( 10.1101/cshperspect.a004697) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mollinedo F, Gajate C. 2015. Lipid rafts as major platforms for signaling regulation in cancer. Adv. Biol. Regul. 57, 130-146. ( 10.1016/j.jbior.2014.10.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mollinedo F, Gajate C. 2020. Lipid rafts as signaling hubs in cancer cell survival/death and invasion: implications in tumor progression and therapy. J. Lipid Res. 61, 611-635. ( 10.1194/jlr.TR119000439) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao X, Zhang J. 2008. Spatiotemporal analysis of differential Akt regulation in plasma membrane microdomains. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 4366-4373. ( 10.1091/mbc.e08-05-0449) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao X, Lowry PR, Zhou X, Depry C, Wei Z, Wong GW, Zhang J. 2011. PI3K/Akt signaling requires spatial compartmentalization in plasma membrane microdomains. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 14 509-14 514. ( 10.1073/pnas.1019386108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugiyama MG, Fairn GD, Antonescu CN. 2019. Akt-ing up just about everywhere: compartment-specific Akt activation and function in receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 7, 70. ( 10.3389/fcell.2019.00070) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamakawa D, et al. 2021. Primary cilia-dependent lipid raft/caveolin dynamics regulate adipogenesis. Cell Rep. 34, 108817. ( 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.108817) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J. 2010. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 141, 1117-1134. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pike LJ. 2005. Growth factor receptors, lipid rafts and caveolae: an evolving story. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1746, 260-273. ( 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.05.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delos Santos RC, Garay C, Antonescu CN. 2015. Charming neighborhoods on the cell surface: plasma membrane microdomains regulate receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Cell Signal. 27, 1963-1976. ( 10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.07.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu SM, Fairn GD. 2018. Mesoscale organization of domains in the plasma membrane—beyond the lipid raft. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 53, 192-207. ( 10.1080/10409238.2018.1436515) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Julien S, Bobowski M, Steenackers A, Le Bourhis X, Delannoy P. 2013. How do gangliosides regulate RTKs signaling? Cells 2, 751-767. ( 10.3390/cells2040751) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Head BP, Patel HH, Insel PA. 2014. Interaction of membrane/lipid rafts with the cytoskeleton: impact on signaling and function: membrane/lipid rafts, mediators of cytoskeletal arrangement and cell signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1838, 532-545. ( 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.07.018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suzuki KGN, Ando H, Komura N, Fujiwara TK, Kiso M, Kusumi A. 2017. Development of new ganglioside probes and unraveling of raft domain structure by single-molecule imaging. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1861, 2494-2506. ( 10.1016/j.bbagen.2017.07.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kraft ML. 2017. Sphingolipid organization in the plasma membrane and the mechanisms that influence it. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 4, 154. ( 10.3389/fcell.2016.00154) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams TM, Lisanti MP. 2004. The caveolin proteins. Genome Biol. 5, 214. ( 10.1186/gb-2004-5-3-214) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sargiacomo M, Scherer PE, Tang Z, Kübler E, Song KS, Sanders MC, Lisanti MP. 1995. Oligomeric structure of caveolin: implications for caveolae membrane organization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 92, 9407. ( 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9407) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nystrom FH, Chen H, Cong LN, Li Y, Quon MJ. 1999. Caveolin-1 interacts with the insulin receptor and can differentially modulate insulin signaling in transfected Cos-7 cells and rat adipose cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 13, 2013-2024. ( 10.1210/mend.13.12.0392) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hill MM, et al. 2008. PTRF-cavin, a conserved cytoplasmic protein required for caveola formation and function. Cell 132, 113-124. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.042) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parpal S, Karlsson M, Thorn H, Strålfors P. 2001. Cholesterol depletion disrupts caveolae and insulin receptor signaling for metabolic control via insulin receptor substrate-1, but not for mitogen-activated protein kinase control. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 9670-9678. ( 10.1074/jbc.M007454200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Couet J, Sargiacomo M, Lisanti MP. 1997. Interaction of a receptor tyrosine kinase, EGF-R, with caveolins: caveolin binding negatively regulates tyrosine and serine/threonine kinase activities. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 30 429-30 438. ( 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30429) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamamoto M, Toya Y, Jensen RA, Ishikawa Y. 1999. Caveolin is an inhibitor of platelet-derived growth factor receptor signaling. Exp. Cell Res. 247, 380-388. ( 10.1006/excr.1998.4379) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Babuke T, Tikkanen R. 2007. Dissecting the molecular function of reggie/flotillin proteins. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 86, 525-532. ( 10.1016/j.ejcb.2007.03.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amaddii M, Meister M, Banning A, Tomasovic A, Mooz J, Rajalingam K, Tikkanen R. 2012. Flotillin-1/reggie-2 protein plays dual role in activation of receptor-tyrosine kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 7265-7278. ( 10.1074/jbc.M111.287599) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tomasovic A, Traub S, Tikkanen R. 2012. Molecular networks in FGF signaling: flotillin-1 and Cbl-associated protein compete for the binding to fibroblast growth factor receptor substrate 2. PLoS ONE 7, e29739. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0029739) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ghaben AL, Scherer PE. 2019. Adipogenesis and metabolic health. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 242-258. ( 10.1038/s41580-018-0093-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vishvanath L, Gupta RK. 2019. Contribution of adipogenesis to healthy adipose tissue expansion in obesity. J. Clin. Invest. 129, 4022-4031. ( 10.1172/jci129191) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Akhmedov D, Berdeaux R. 2013. The effects of obesity on skeletal muscle regeneration. Front. Physiol. 4, 371. ( 10.3389/fphys.2013.00371) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Veldhuis-Vlug AG, Rosen CJ. 2018. Clinical implications of bone marrow adiposity. J. Intern. Med. 283, 121-139. ( 10.1111/joim.12718) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haczeyni F, Bell-Anderson KS, Farrell GC. 2018. Causes and mechanisms of adipocyte enlargement and adipose expansion. Obes. Rev. 19, 406-420. ( 10.1111/obr.12646) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu D, Shi S, Wang H, Liao K. 2009. Growth arrest induces primary-cilium formation and sensitizes IGF-1-receptor signaling during differentiation induction of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. J. Cell Sci. 122, 2760-2768. ( 10.1242/jcs.046276) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dalbay MT, Thorpe SD, Connelly JT, Chapple JP, Knight MM. 2015. Adipogenic differentiation of hMSCs is mediated by recruitment of IGF-1r onto the primary cilium associated with cilia elongation. Stem Cells (Dayton, Ohio) 33, 1952-1961. ( 10.1002/stem.1975) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taniguchi CM, Emanuelli B, Kahn CR. 2006. Critical nodes in signalling pathways: insights into insulin action. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 85-96. ( 10.1038/nrm1837) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen J, Lu Y, Tian M, Huang Q. 2019. Molecular mechanisms of FOXO1 in adipocyte differentiation. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 62, R239-R253. ( 10.1530/jme-18-0178) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gerdes JM, et al. 2014. Ciliary dysfunction impairs beta-cell insulin secretion and promotes development of type 2 diabetes in rodents. Nat. Commun. 5, 5308. ( 10.1038/ncomms6308) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Starks RD, Beyer AM, Guo DF, Boland L, Zhang Q, Sheffield VC, Rahmouni K. 2015. Regulation of insulin receptor trafficking by Bardet Biedl syndrome proteins. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005311. ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005311) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mourão A, Christensen ST, Lorentzen E. 2016. The intraflagellar transport machinery in ciliary signaling. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 41, 98-108. ( 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.06.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hilgendorf KI, et al. 2019. Omega-3 fatty acids activate ciliary FFAR4 to control adipogenesis. Cell 179, 1289-1305.e21. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2019.11.005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kopinke D, Roberson EC, Reiter JF. 2017. Ciliary hedgehog signaling restricts injury-induced adipogenesis. Cell 170, 340-351.e12. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.035) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nechipurenko IV. 2020. The enigmatic role of lipids in cilia signaling. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8, 777. ( 10.3389/fcell.2020.00777) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nishizawa M, Izawa I, Inoko A, Hayashi Y, Nagata K, Yokoyama T, Usukura J, Inagaki M. 2005. Identification of trichoplein, a novel keratin filament-binding protein. J. Cell Sci. 118, 1081-1090. ( 10.1242/jcs.01667) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ibi M, et al. 2011. Trichoplein controls microtubule anchoring at the centrosome by binding to Odf2 and ninein. J. Cell Sci. 124, 857-864. ( 10.1242/jcs.075705) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Inoko A, et al. 2012. Trichoplein and Aurora A block aberrant primary cilia assembly in proliferating cells. J. Cell Biol. 197, 391-405. ( 10.1083/jcb.201106101) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kasahara K, Kawakami Y, Kiyono T, Yonemura S, Kawamura Y, Era S, Matsuzaki F, Goshima N, Inagaki M. 2014. Ubiquitin-proteasome system controls ciliogenesis at the initial step of axoneme extension. Nat. Commun. 5, 5081. ( 10.1038/ncomms6081) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Inaba H, et al. 2016. Ndel1 suppresses ciliogenesis in proliferating cells by regulating the trichoplein-Aurora A pathway. J. Cell Biol. 212, 409-423. ( 10.1083/jcb.201507046) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kasahara K, et al. 2018. EGF receptor kinase suppresses ciliogenesis through activation of USP8 deubiquitinase. Nat. Commun. 9, 758. ( 10.1038/s41467-018-03117-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huo H, Guo X, Hong S, Jiang M, Liu X, Liao K. 2003. Lipid rafts/caveolae are essential for insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor signaling during 3T3-L1 preadipocyte differentiation induction. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 11 561-11 569. ( 10.1074/jbc.M211785200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sánchez-Wandelmer J, Dávalos A, Herrera E, Giera M, Cano S, de la Peña G, Lasunción MA, Busto R. 2009. Inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis disrupts lipid raft/caveolae and affects insulin receptor activation in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1788, 1731-1739. ( 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.05.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stahlhut M, van Deurs B. 2000. Identification of filamin as a novel ligand for caveolin-1: evidence for the organization of caveolin-1-associated membrane domains by the actin cytoskeleton. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 325-337. ( 10.1091/mbc.11.1.325) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dufour J, Viennois E, De Boussac H, Baron S, Lobaccaro JM. 2012. Oxysterol receptors, AKT and prostate cancer. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 12, 724-728. ( 10.1016/j.coph.2012.06.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Beloribi-Djefaflia S, Vasseur S, Guillaumond F. 2016. Lipid metabolic reprogramming in cancer cells. Oncogenesis 5, e189. ( 10.1038/oncsis.2015.49) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hryniewicz-Jankowska A, Augoff K, Sikorski AF. 2019. The role of cholesterol and cholesterol-driven membrane raft domains in prostate cancer. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 244, 1053-1061. ( 10.1177/1535370219870771) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vona R, Iessi E, Matarrese P. 2021. Role of cholesterol and lipid rafts in cancer signaling: a promising therapeutic opportunity? Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 622908. ( 10.3389/fcell.2021.622908) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cole PA, Chu N, Salguero AL, Bae H. 2019. AKTivation mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 59, 47-53. ( 10.1016/j.sbi.2019.02.004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rodgers JT, Vogel RO, Puigserver P. 2011. Clk2 and B56β mediate insulin-regulated assembly of the PP2A phosphatase holoenzyme complex on Akt. Mol. Cell 41, 471-479. ( 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Davies MA, et al. 2009. Integrated molecular and clinical analysis of AKT activation in metastatic melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 7538-7546. ( 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-09-1985) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mulholland DJ, et al. 2011. Cell autonomous role of PTEN in regulating castration-resistant prostate cancer growth. Cancer Cell 19, 792-804. ( 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.05.006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Perrotti D, Neviani P. 2013. Protein phosphatase 2A: a target for anticancer therapy. Lancet Oncol. 14, e229-e238. ( 10.1016/s1470-2045(12)70558-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ruvolo PP. 2016. The broken ‘Off’ switch in cancer signaling: PP2A as a regulator of tumorigenesis, drug resistance, and immune surveillance. BBA Clin. 6, 87-99. ( 10.1016/j.bbacli.2016.08.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhuang L, Kim J, Adam RM, Solomon KR, Freeman MR. 2005. Cholesterol targeting alters lipid raft composition and cell survival in prostate cancer cells and xenografts. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 959-968. ( 10.1172/jci19935) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li L, Ren CH, Tahir SA, Ren C, Thompson TC. 2003. Caveolin-1 maintains activated Akt in prostate cancer cells through scaffolding domain binding site interactions with and inhibition of serine/threonine protein phosphatases PP1 and PP2A. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 9389-9404. ( 10.1128/mcb.23.24.9389-9404.2003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fedida-Metula S, Feldman B, Koshelev V, Levin-Gromiko U, Voronov E, Fishman D. 2012. Lipid rafts couple store-operated Ca2+ entry to constitutive activation of PKB/Akt in a Ca2+/calmodulin-, Src- and PP2A-mediated pathway and promote melanoma tumor growth. Carcinogenesis 33, 740-750. ( 10.1093/carcin/bgs021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jeon TI, Osborne TF. 2012. SREBPs: metabolic integrators in physiology and metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 23, 65-72. ( 10.1016/j.tem.2011.10.004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Grunt TW. 2018. Interacting cancer machineries: cell signaling, lipid metabolism, and epigenetics. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 29, 86-98. ( 10.1016/j.tem.2017.11.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Butler LM, Perone Y, Dehairs J, Lupien LE, de Laat V, Talebi A, Loda M, Kinlaw WB, Swinnen JV. 2020. Lipids and cancer: emerging roles in pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapeutic intervention. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 159, 245-293. ( 10.1016/j.addr.2020.07.013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yamauchi Y, Furukawa K, Hamamura K, Furukawa K. 2011. Positive feedback loop between PI3K-Akt-mTORC1 signaling and the lipogenic pathway boosts Akt signaling: induction of the lipogenic pathway by a melanoma antigen. Cancer Res. 71, 4989-4997. ( 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-10-4108) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gu L, Saha ST, Thomas J, Kaur M. 2019. Targeting cellular cholesterol for anticancer therapy. FEBS J. 286, 4192-4208. ( 10.1111/febs.15018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yang J, Nie J, Ma X, Wei Y, Peng Y, Wei X. 2019. Targeting PI3K in cancer: mechanisms and advances in clinical trials. Mol. Cancer 18, 26. ( 10.1186/s12943-019-0954-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Boosani CS, Gunasekar P, Agrawal DK. 2019. An update on PTEN modulators—a patent review. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 29, 881-889. ( 10.1080/13543776.2019.1669562) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Braglia L, Zavatti M, Vinceti M, Martelli AM, Marmiroli S. 2020. Deregulated PTEN/PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling in prostate cancer: still a potential druggable target? Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 1867, 118731. ( 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2020.118731) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shah VM, English IA, Sears RC. 2020. Select stabilization of a tumor-suppressive PP2A heterotrimer. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 41, 595-597. ( 10.1016/j.tips.2020.06.008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zalba S, ten Hagen TLM. 2017. Cell membrane modulation as adjuvant in cancer therapy. Cancer Treat. Rev. 52, 48-57. ( 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.10.008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hoxhaj G, Manning BD. 2020. The PI3K–AKT network at the interface of oncogenic signalling and cancer metabolism. Nat. Rev. Cancer 20, 74-88. ( 10.1038/s41568-019-0216-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kim J, Dabiri S, Seeley ES. 2011. Primary cilium depletion typifies cutaneous melanoma in situ and malignant melanoma. PloS ONE 6, e27410. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0027410) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hassounah NB, Nagle R, Saboda K, Roe DJ, Dalkin BL, McDermott KM. 2013. Primary cilia are lost in preinvasive and invasive prostate cancer. PloS ONE 8, e68521. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0068521) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fabbri L, Bost F, Mazure NM. 2019. Primary cilium in cancer hallmarks. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 1336. ( 10.3390/ijms20061336) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Choudhury A, Neumann NM, Raleigh DR, Lang UE. 2020. Clinical implications of primary cilia in skin cancer. Dermatol. Ther. (Heidelb) 10, 233-248. ( 10.1007/s13555-020-00355-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Coelho PA, et al. 2015. Over-expression of Plk4 induces centrosome amplification, loss of primary cilia and associated tissue hyperplasia in the mouse. Open Biol. 5, 150209. ( 10.1098/rsob.150209) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gijs HL, et al. 2015. Primary cilium suppression by SREBP1c involves distortion of vesicular trafficking by PLA2G3. Mol. Biol. Cell 26, 2321-2332. ( 10.1091/mbc.E14-10-1472) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Willemarck N, et al. 2010. Aberrant activation of fatty acid synthesis suppresses primary cilium formation and distorts tissue development. Cancer Res. 70, 9453-9462. ( 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-10-2324) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jamal MH, Nunes ACF, Vaziri ND, Ramchandran R, Bacallao RL, Nauli AM, Nauli SM. 2020. Rapamycin treatment correlates changes in primary cilia expression with cell cycle regulation in epithelial cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 178, 114056. ( 10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114056) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Liu H, Kiseleva AA, Golemis EA. 2018. Ciliary signalling in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 18, 511-524. ( 10.1038/s41568-018-0023-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hryniewicz-Jankowska A, Augoff K, Biernatowska A, Podkalicka J, Sikorski AF. 2014. Membrane rafts as a novel target in cancer therapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1845, 155-165. ( 10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.01.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Greenlee JD, Subramanian T, Liu K, King MR. 2021. Rafting down the metastatic cascade: the role of lipid rafts in cancer metastasis, cell death, and clinical outcomes. Cancer Res. 81, 5. ( 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-2199) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pommier AJC, et al. 2010. Liver X receptor activation downregulates AKT survival signaling in lipid rafts and induces apoptosis of prostate cancer cells. Oncogene 29, 2712-2723. ( 10.1038/onc.2010.30) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Carbonnelle D, Luu TH, Chaillou C, Huvelin J-M, Bard J-M, Nazih H. 2017. LXR activation down-regulates lipid raft markers FLOT2 and DHHC5 in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 37, 4067. ( 10.21873/anticanres.11792) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Park EK, et al. 2010. Induction of apoptosis by the ginsenoside Rh2 by internalization of lipid rafts and caveolae and inactivation of Akt. Br. J. Pharmacol. 160, 1212-1223. ( 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00768.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Reis-Sobreiro M, Roué G, Moros A, Gajate C, de la Iglesia-Vicente J, Colomer D, Mollinedo F. 2013. Lipid raft-mediated Akt signaling as a therapeutic target in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood Cancer J. 3, e118. ( 10.1038/bcj.2013.15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Fessler MB. 2018. The challenges and promise of targeting the liver X receptors for treatment of inflammatory disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 181, 1-12. ( 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.07.010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Buñay J, et al. 2021. Screening for liver X receptor modulators: where are we and for what use? Br. J. Pharmacol. 178, 3277-3293. ( 10.1111/bph.15286) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Verstraeten SL, Lorent JH, Mingeot-Leclercq M-P. 2020. Lipid membranes as key targets for the pharmacological actions of ginsenosides. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 1391. ( 10.3389/fphar.2020.576887) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kim J, Lee JE, Heynen-Genel S, Suyama E, Ono K, Lee K, Ideker T, Aza-Blanc P, Gleeson JG. 2010. Functional genomic screen for modulators of ciliogenesis and cilium length. Nature 464, 1048-1051. ( 10.1038/nature08895) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Jacob LS, et al. 2011. Genome-wide RNAi screen reveals disease-associated genes that are common to Hedgehog and Wnt signaling. Sci. Sig. 4, ra4. ( 10.1126/scisignal.2001225) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Szymanska K, et al. 2015. A high-throughput genome-wide siRNA screen for ciliogenesis identifies new ciliary functional components and ciliopathy genes. Cilia 4, O12. ( 10.1186/2046-2530-4-S1-O12) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kim JH, et al. 2016. Genome-wide screen identifies novel machineries required for both ciliogenesis and cell cycle arrest upon serum starvation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1863, 1307-1318. ( 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.03.021) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Failler M, et al. 2021. Whole-genome screen identifies diverse pathways that negatively regulate ciliogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 32, 169-185. ( 10.1091/mbc.E20-02-0111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Shearer RF, Saunders DN. 2016. Regulation of primary cilia formation by the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 44, 1265-1271. ( 10.1042/bst20160174) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hossain D, Tsang WY. 2019. The role of ubiquitination in the regulation of primary cilia assembly and disassembly. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 93, 145-152. ( 10.1016/j.semcdb.2018.09.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Shiromizu T, Yuge M, Kasahara K, Yamakawa D, Matsui T, Bessho Y, Inagaki M, Nishimura Y. 2020. Targeting E3 ubiquitin ligases and deubiquitinases in ciliopathy and cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 5962. ( 10.3390/ijms21175962) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Perez-Cervera Y, Dehennaut V, Gil MA, Guedri K, Mata CJS, Stichelen SO-V, Michalski J-C, Foulquier F, Lefebvre T. 2013. Insulin signaling controls the expression of O-GlcNAc transferase and its interaction with lipid microdomains. FASEB J. 27, 3478-3486. ( 10.1096/fj.12-217984) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Very N, Vercoutter-Edouart AS, Lefebvre T, Hardivillé S, El Yazidi-Belkoura I. 2018. Cross-dysregulation of O-GlcNAcylation and PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis in human chronic diseases. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 9, 602. ( 10.3389/fendo.2018.00602) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Tian JL, Qin H. 2019. O-GlcNAcylation regulates primary ciliary length by promoting microtubule disassembly. iScience 12, 379-391. ( 10.1016/j.isci.2019.01.031) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Yuan A, Tang X, Li J. 2020. Centrosomes: til O-GlcNAc do us apart. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 11, 621888. ( 10.3389/fendo.2020.621888) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ferrer CM, Sodi VL, Reginato MJ. 2016. O-GlcNAcylation in cancer biology: linking metabolism and signaling. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 3282-3294. ( 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.05.028) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Tian JL, Gomeshtapeh FI. 2020. Potential roles of O-GlcNAcylation in primary cilia-mediated energy metabolism. Biomolecules 10, 1504. ( 10.3390/biom10111504) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Yang Y, et al. 2020. O-GlcNAc transferase inhibits visceral fat lipolysis and promotes diet-induced obesity. Nat. Commun. 11, 181. ( 10.1038/s41467-019-13914-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Carmena M, Earnshaw WC, Glover DM. 2015. The dawn of aurora kinase research: from fly genetics to the clinic. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 3, 73. ( 10.3389/fcell.2015.00073) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Korobeynikov V, Deneka AY, Golemis EA. 2017. Mechanisms for nonmitotic activation of Aurora-A at cilia. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 45, 37-49. ( 10.1042/bst20160142) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ritter A, Kreis NN, Roth S, Friemel A, Jennewein L, Eichbaum C, Solbach C, Louwen F, Yuan J. 2019. Restoration of primary cilia in obese adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells by inhibiting Aurora A or extracellular signal-regulated kinase. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 10, 255. ( 10.1186/s13287-019-1373-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Huang X-F, Chen J-Z. 2009. Obesity, the PI3K/Akt signal pathway and colon cancer. Obes. Rev. 10, 610-616. ( 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00607.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wang Q, Chen X, Hay N. 2017. Akt as a target for cancer therapy: more is not always better (lessons from studies in mice). Br. J. Cancer 117, 159-163. ( 10.1038/bjc.2017.153) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This article has no additional data.